LucidLink Offers Streaming Vision of Cloud-Based Storage

When I was deep in researching details related to Dropbox migrating to Apple’s File Provider extension (see “Apple’s File Provider Forces Mac Cloud Storage Changes,” 10 March 2023), I was intrigued to see comments from people in the media world, where I have little experience. These folks inhabit an entirely different digital reality from everyday users who are happy with 1 TB of internal storage. User millifoo wrote:

We use cloud sync with our external huge drives to allow collaboration with audio/video editing. The workflow for lots of media houses with people who collaborate in multiple locations requires files be local (speed of editing and playback), and sync through the cloud not only facilitates that, it also backs up all the files in case of catastrophe.

Others noted that Dropbox’s plans don’t provide enough storage. The Plus and Family plans include 2 TB, the Professional plan is 3 TB, and the Standard team plan comes with 5 TB. Only the Advanced plan, at $24 per user per month, allows for more storage. How much do these media folks need? KyleKoch noted:

There are many of us who require Dropbox to be on external drives when media is local. The logistics to manage video assets within a Dropbox folder located on the OS drive does not make any sense when you have a 50TB+ of cloud storage.

User solldavid concurred:

We have the advanced plan and are up to 200+ TB of assets in the Dropbox cloud, all visible and searchable in OSX Finder via “online-only”, and restorable with a full bandwidth download. It’s the best product in the industry imo. Yes, you need a minimum of three “users”.

Unfortunately, on topic with the thread, this change from Apple and Dropbox threatens my whole workflow. We keep 3-6TB available offline at a time to keep large video, GFX, and 3D files in sync across remote workstations, and we’ve been doing it with external SSDs successfully since 2012. It’s been the cornerstone of our workflow, super reliable, plenty fast, and I don’t know what I would have done without it.

And user jmeredi2 said:

We have a business advanced plan with 6 users that we pay about $1,700/ year for. This is an unlimited plan, so every time we reach our storage limit, they give us more space. Unfortunately this obviously won’t work anymore with the DropBox “upgrade” unless I can find computers with 30-40 TB internal hard drives.

I recognize that many people require more than a terabyte or two of cloud storage, but these comments gave me a peek into professional media demands. I share this as context because soon after my article appeared, I heard from TidBITS reader Steven Niedzielski about how LucidLink, the company he works for, provides streamed cloud storage for high-performance media users. I was curious to learn more, even if the system is overkill for most of the rest of us.

LucidLink Rethinks Cloud Storage

The backdrop to my previous article was Apple’s File Provider extension, which offers a coherent approach for “sync-and-share” services like Box, Dropbox, Google Drive, and Microsoft OneDrive.

They all rely on an architecture that’s relatively simple, conceptually speaking. All your files are stored online and can be accessed via a Web interface. Client software for different operating systems syncs that data store to devices, either with full content (offline) or in placeholder form (online-only). If you need to work on an online-only file, it must be downloaded in its entirety before you can access it. Changes, including additions, deletions, and adjustments to the directory structure, are synced from a client first back to the cloud and then down to all the other connected clients. Some of those changes may rely on a diff approach, where only the changed bits of a particular file need to be transferred; in other cases, the entire file must be sent back.

LucidLink doesn’t work that way. On the Mac, it leans on MacFUSE to mount LucidLink’s proprietary Filespace cloud-native file system as a standard Mac volume. (LucidLink is also available for Windows and Linux.) Think for a moment about that. You interact with what looks like a normal external or network drive in the Finder, but what’s behind it is data in a cloud-native file system. Thus, opening a file from LucidLink works in the same way as opening a file from a Mac’s internal SSD, though it reads and writes data in blocks of 256 kilobytes, whereas the default block size for macOS local storage is 4096 bytes.

That means LucidLink has no need to sync a file in its entirety before opening it, as would be the case for an online-only file in Dropbox, say. With small files, the syncing approach works well enough, but with the size of files used in the media world, retrieving a file from the cloud takes significant time—hence the need for large external drives to store local versions.

I’ve long thought MacFUSE was a brilliant way to integrate unusual file systems into the Mac experience, so I understood what LucidLink was doing. However, I immediately asked Niedzielski how much bandwidth LucidLink needed, expecting him to admit that a 1 Gbps fiber connection was necessary and that serious video professionals all had such connectivity.

Instead, he said that 50 Mbps down and 10 Mbps up was a realistic minimum for non-video work. In an ideal video world, he noted that you’d want to match the bandwidth of your video stream for seamless behavior. I don’t think of video in terms of bandwidth, but I suspect that the more you have, the better—that fiber connection might be a good idea. One hands-on review said that LucidLink worked well with 230 Mbps down, though that was seemingly in a proxy workflow scenario, where most edits involved smaller proxy files. Low latency is also important, and LucidLink’s interface reports on that (also see “Use Apple’s networkQuality Tool to Test Internet Responsiveness,” 22 April 2022).

Important though bandwidth is, anyone using Dropbox or a similar service will have to store all that data locally anyway. LucidLink also relies on a fast local cache to improve performance. It defaults to 5 GB on the internal drive, but you can repoint it to an external drive and increase it to 10 TB. Plus, if you know you will be working on certain files, you can “pin” them to pre-load them into the local cache. Even with pinned files, LucidLink uploads only diffed data at the block level, so it doesn’t have to transfer entire files for small changes.

One downside to LucidLink’s approach is that you cannot work offline, even with pinned files. Because it has a single source of truth in the cloud, users need to maintain Internet connectivity for the service to work. The local cache is just that, a cache, not an independent copy of files.

There’s another downside of sorts to LucidLink’s caching approach. Some Dropbox users see the “sync-and-share” architecture as providing a backup. It’s not, of course, since any user with appropriate permissions can inadvertently or maliciously delete files, but you do end up with multiple copies in most situations. LucidLink’s local cache doesn’t provide even that.

However, LucidLink’s Filespace file system offers automatic snapshots, just like APFS. (Some LucidLink plans let you create custom snapshot schedules.) Snapshots record the exact state of your files at that point in time, making it easy to recover deleted, corrupted, or changed files. They use space efficiently, recording only the block-level data that has changed between two snapshots. Even better, snapshots are read-only, so they also provide a defense against ransomware attacks that attempt to destroy backups.

Nonetheless, LucidLink encourages backups. Niedzielski said that the company considers LucidLink a “hot active collaboration space” and recommends that users maintain a separate copy of all files. That could be on a local NAS device or in the cloud to a service like Backblaze B2 or Wasabi. He also mentioned that some clients rely on a data management service called CloudSoda to migrate and protect their LucidLink data—we’re talking about serious enterprise-level capabilities here.

There’s no question that LucidLink is aimed at the business world, whether media houses, medical imaging groups, or game development teams. Even the US Department of Treasury is a LucidLink customer. And if you’re hesitant about paying $9.99 per month for 2 TB of storage from the likes of Dropbox, Google Drive, or iCloud Drive, LucidLink is overkill.

But it’s not out of the question. LucidLink’s Basic Filespace plan costs $20 per terabyte per month for up to five users—additional users each cost $10 per month. That’s twice as much per month for half the storage with a consumer-level service, which is expensive but manageable for a freelancer or small office. The Advanced Filespace plan costs $80 per terabyte per month, again with five users, but uses IBM storage rather than Wasabi storage for higher performance, provides custom snapshot schedules, and offers single sign-on integration.

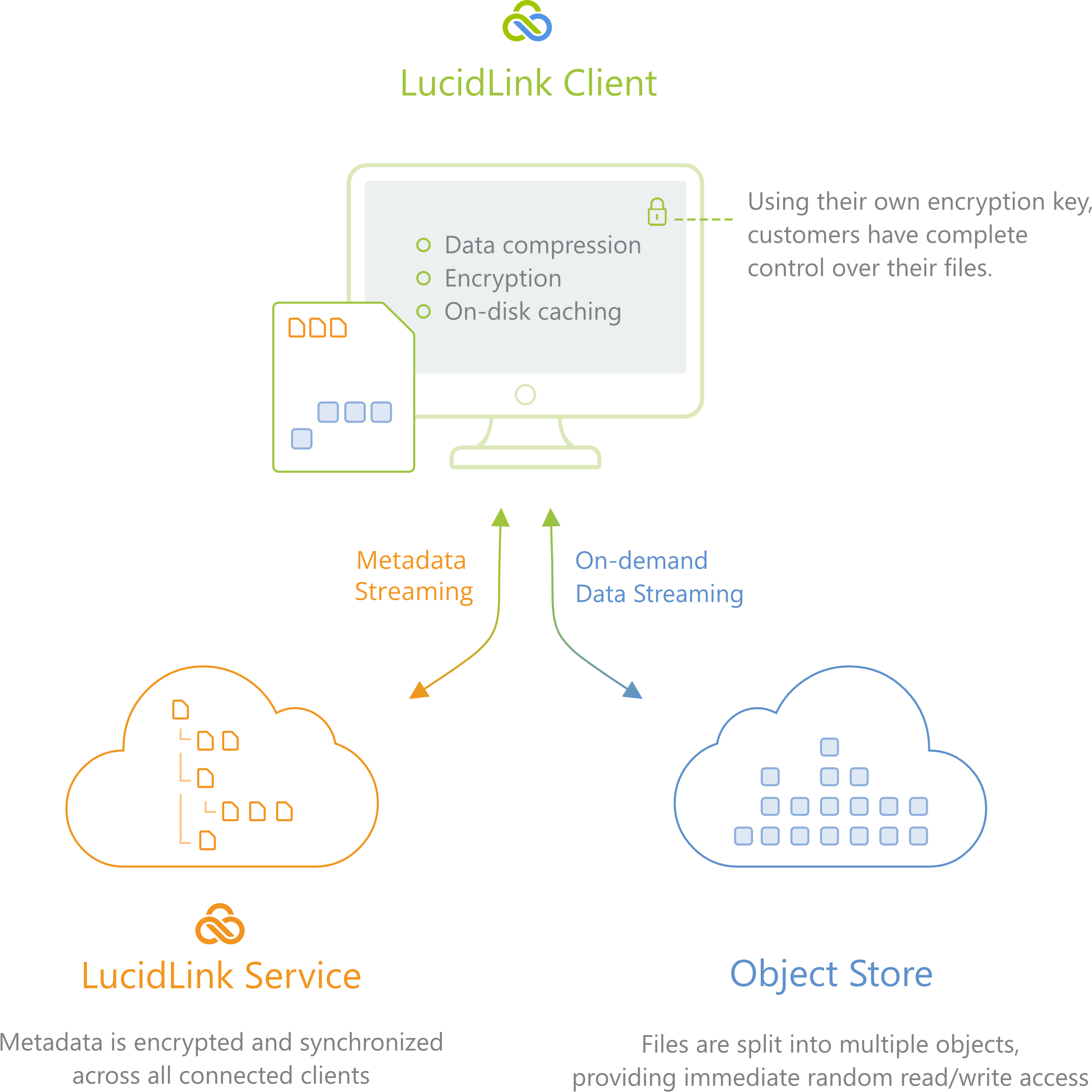

It’s worth noting that there are actually three parts to LucidLink: the LucidLink Client running on your Mac, the LucidLink Service that manages the metadata and snapshots, and the Object Storage, which is any S3- or Azure-compliant storage system. That explains the Custom Filespace plan, which is just $40 per terabyte per month but lets you provide your own storage. However, the Wasabi and IBM storage in the other plans doesn’t come with egress fees, which most cloud storage providers charge to retrieve data. With a lot of data access, egress fees could add up quickly and unpredictably.

From a security standpoint, LucidLink claims a “zero-knowledge” approach. The LucidLink Client provides end-to-end encryption, with only the user holding the encryption keys. Plus, the LucidLink Service never sees your data, just its metadata, and the data at the storage provider is encrypted at rest. It seems very well thought-out.

There’s no reason to switch to LucidLink from the likes of Dropbox, Google Drive, or iCloud Drive if all you need is cloud storage and basic collaboration. However, if you’re pushing against the limitations of those services, particularly with audio or video work, LucidLink is worth a look.

More generally, I’m pondering whether there’s a larger role for streamed online storage that looks and feels like local storage. Free space concerns could become a thing of the past if our devices could access theoretically unlimited amounts of storage online at any time. Caching would still be useful for performance reasons and possibly for eliminating the need for constant connectivity, but we’d always have as much storage as we needed… and were willing to pay for, of course.

Thank you very much for bringing this type of service to our attention. Another reason to support TidBits.

Thanks! I know that LucidLink won’t be of interest to a lot of TidBITS readers, and I would be unlikely to use it myself. But it’s such a cool technical approach, and those who have been complaining about the difficulty of working with a video workflow with Google Drive or the like should definitely give it a look.

It’s a really interesting concept, thanks for pointing it out! I work for a prepress/printshop company, and we have yet to find a solution for our prepress people to work from home. The large InDesign / Photoshop files just don’t work over normal VPNs, so LucidLink looks promising.

In my first tests, it seems to be working pretty well – the only big downside I see is that it requires a kernel extension for the MacFUSE filesystem, which Apple has (for good reason) made very cumbersome to install.