TidBITS#1114/20-Feb-2012

The big news this week — and nearly our entire issue — revolves around OS X 10.8 Mountain Lion, which Apple has released in developer preview form. Rich Mogull, who was briefed early by Apple due to his position in the Macintosh security world, explains what’s new and interesting about Mountain Lion and then goes into more depth about Gatekeeper, the new security technology in Mountain Lion that promises to eliminate the possibility of a malware epidemic. For those still living in the present, Adam explains how he tracked down and eliminated a troubling performance problem in 10.7 Lion. Notable software releases this week include Default Folder X 4.4.9, VLC 2.0, Bookle 1.0.4, and Airfoil 4.6.5.

Solving iCloud-Related Slowdowns in Lion

I recently solved some maddening performance problems on my original aluminum MacBook running Mac OS X 10.7 Lion, and I wanted to share my findings to help others avoid similar troubles. Most interesting about the problems was the technique I happened on for isolating the culprits, which revolved not around raw performance, but battery life.

I needed to spend the entire plane flight out to Macworld editing a book, but I knew my MacBook’s battery, even though I had just replaced it, would have trouble lasting the long flight from Detroit to San Francisco. So I turned my screen brightness down to the lowest level, shut off Wi-Fi and Bluetooth, and set my Energy Saver settings to their most parsimonious.

But here’s the thing about battery life on modern laptop Macs — it’s driven as much by CPU activity as anything else. That is, your MacBook may feel reasonably snappy, but if one of the Intel Core 2 Duo’s cores is being monopolized by an errant application, your battery life will suffer tremendously.

The worst program from this respect, in my experience, is Firefox. That’s partly because I tend to have a number of open tabs, each of which might have some sort of dynamic aspect generated by JavaScript or Flash and running constantly in the background. But whatever the reason, when I opened Activity Monitor on my MacBook, Firefox would usually be using more CPU than any other application. For that reason, I’ve switched to Google Chrome on the MacBook; Chrome isolates each tab as an independent process, making it easier to see if a particular tab is causing problems and stop it. Even more important, Chrome runs Flash as yet another process called Shockwave Flash (Chrome Plug-in Host), so it’s easy to see in Activity Monitor when

Flash is causing problems and, if so, quit that process.

Knowing this, and since I had Wi-Fi off on the plane anyway, I quit Google Chrome, so the only applications that I was using were Pages, where I was editing, BBEdit, which is what the book is about, and Keyboard Maestro, which I was using to make Pages more keyboard-oriented. I figured this would be a rather minimal load and might give me as much as 4 hours of battery life.

So I was rather distressed when I glanced up at the battery life estimate indicator after 15 or 20 minutes of editing and saw that it was predicting only about 2 hours. What could possibly be eating my precious battery power?

A quick trip to Activity Monitor revealed that a process I’d never seen before, called Mingler, was using nearly an entire core — it was hovering at about 97 percent CPU usage. (Activity Monitor’s percentages are by core, so if you have a 12-core Mac Pro, 12 different processes could each be listed as using 100 percent.) I quit Mingler from within Activity Monitor, made a mental note to figure out what it was, and went on with my work. My battery life estimates improved, but the damage was done, and I was able to work for less than 3 hours.

Roughly the same thing happened on the flight back, but once at home, performance actually got worse, and another culprit reared its ugly head in Activity Monitor. This one was a smoking gun, since its name was SafariDAVClient. Some quick research on the Internet revealed that SafariDAVClient and Mingler are both related to iCloud bookmark syncing. (Although I don’t use Safari as my main browser, I do use it for certain tasks, and iCloud bookmark syncing is a good way to manage the Safari bookmarks on my iPhone.)

Since iCloud stores the master copy of bookmarks in the cloud, I simply turned off bookmark syncing in the iCloud pane of System Preferences, renamed the Bookmarks.plist file in ~/Library/Safari to oldBookmarks.plist (see “Dealing with Lion’s Hidden Library,” 20 July 2011), and turned bookmark syncing back on. A new copy of my bookmarks was retrieved from iCloud, and I haven’t seen SafariDAVClient and Mingler since. (I assume they’re still doing their job, but with nothing much to do, they presumably launch and quit silently in the background.)

The problem, therefore, was a somewhat corrupted Bookmarks.plist file in Safari that was causing iCloud bookmark syncing to choke in such a way as to use a vast amount of processing power, and, in the process, battery power.

I realize this is all very specific, and if you’re experiencing notable performance problems in Lion, it’s certainly worth seeing if either Firefox or iCloud bookmark syncing is the culprit. But realistically, it’s unlikely that either would be your particular problem. You can, however, use roughly the same technique I did, in terms of keeping Activity Monitor running, with the list sorted by the %CPU column, and seeing if anything unusual seems to be bubbling up at the top of the list.

And of course, if you’re interested in a complete discussion of performance issues on the Mac, Joe Kissell’s “Take Control of Speeding Up Your Mac” is the definitive source. We have a minor update to that title to add Lion-specific information coming very soon; it will be free to all owners of the book.

OS X 10.8 Mountain Lion Stalks iOS

Starting 16 February 2012, Apple has made available a developer preview of OS X 10.8 Mountain Lion, announcing plans to release the new operating system version this summer (or winter, for our friends in the Southern hemisphere), and dropping the word “Mac” from the name in the process.

This upgrade from 10.7 Lion to 10.8 Mountain Lion isn’t meant to be a major overhaul like the one we saw moving from 10.6 Snow Leopard to 10.7 Lion. The core user experience remains largely the same, with a series of enhancements that build on the changes made in Lion. Since Mountain Lion is only in pre-release you shouldn’t take this article as a review. Not all of the features were enabled on the demonstration system provided to me by Apple, and much is likely to change before it’s released to the public.

Living in the iCloud — Mountain Lion unifies the experience between iOS and the Mac while still maintaining those differences that are important to each platform. Notably, iCloud becomes the glue of the Apple ecosystem, playing a stronger role than we’ve seen before. For example, the first time you set up a user account, Mountain Lion prompts you for iCloud credentials and loads all your information and even Mac App Store purchases (unless you use a different Apple ID for iCloud and the Mac App Store). In a nice return to the days of MobileMe, you can even synchronize your Mail, Contacts, and

Calendar accounts if they have been configured on another Mountain Lion-using Mac connected to your iCloud account. (Oh, and iCal and Address Book have been renamed to match iOS, so they’re now Calendars and Contacts.)

iCloud’s Documents in the Cloud service gains several enhancements. For example, in a demo by Apple, I saw that as you edit a document on an iOS device, the updates are pushed immediately to a Mac version of the document even if it’s open in the Mac application. And, Mountain Lion debuts a new Document Library where you can choose between iCloud documents and local files.

Mountain Lion also brings over more features from iOS, while tuning them to work better with a desktop operating system. While this includes some apps, the more-important changes are three new system-wide features: Notifications, Share Sheets, and Twitter.

Notification Center — In the short time I’ve used Mountain Lion, I’ve found Notification Center to be highly useful, even if only a few applications support it. A notification is a brief message that appears onscreen, alerting you to something like a new incoming text message, a calendar event, or the next move in a multiplayer game. Fortunately, notifications are highly configurable, so you can control which aspects of your digital life become notifications. At the moment, Notification Center offers two types of notifications — banners that appear for a short time before

disappearing, and alerts that stay until you click to close them or jump into the alerting application.

To see your notifications, you use a two-finger swipe from the edge of a trackpad or click the small notification icon located on the far right of the menu bar. Your Desktop slides a bit to the left to show a column of notifications in exactly the same style as the iOS Notification Center. It’s an extremely intuitive action and nice for glancing at things like new email messages or calendar appointments.

Since Apple Mail is likely to be a heavy pusher of notifications, it gains a new Favorites mark so you can pick which contacts’ messages trigger notifications. This is also used in Share Sheets, discussed below.

At first, I thought that bringing Notification Center to OS X would mean the end of the popular Growl notification tool, but the more I use Notification Center, the more I think that Growl retains an important role for those of us who need more flexibility in how notifications appear or advanced functions like sending notifications across computers.

As with most of the features I discuss in this article, Apple is supporting notifications with a new API for developers, so that developers can integrate notifications into their own programs.

Share Sheets — Share Sheets adds a new button to supporting apps to “send” the current item to another application. This feature functions like the “Open In” feature in iOS, enabling you to share content directly between applications without cutting and pasting. (It’s kind of a simplified Services menu item, and will hopefully see more use than Services.)

Share Sheets focuses on photos, videos, links, and documents, and it enables you to share to other applications and online services, and even send files directly to AirDrop. Share Sheets are context-aware, so if you are sharing a note, you can send it to Mail or Messages, but not to iPhoto. For files in the Finder, you can share directly from Quick Look windows. And if you are on a Web page you can, with a few clicks, share the full page in an email message, or as a link in Twitter.

Did I mention Twitter?

Twitter, Safari, and Web Sharing — As with iOS, Twitter is integrated deeply into Mountain Lion. Once you add your Twitter account in the updated Mail, Contacts, and Calendars preference pane, you can send content right to Twitter using Share Sheets.

See a Web page you like? You no longer need to cut and paste into your favorite Twitter application, but can instead send it directly from Safari. There’s also integration with your contacts (though I have yet to figure out how that works). When you create a new tweet, an input window pops up in whatever application you are in (instead of switching to a Twitter app), and you can choose to reveal your location down to the city level.

Apple also added support for Flickr and Vimeo accounts for photo and video sharing, along with support for some of the most popular Chinese photo and video sharing services as part of a series of system-wide enhancements for Chinese Mac users, showing how seriously Apple takes that market.

Safari steals a cue from Google Chrome and finally moves to a single address bar for search and Web addresses. Typing into the address bar will either take you to an address or run a search on the search engine of your choice. When I migrated my user account from my regular Mac, it retained Bing as my preferred engine.

Notes and Reminders — Two iOS apps, Notes and Reminders, make their Mac debut. Notes replaces Stickies and is fully iCloud-compatible. Aside from keeping your notes in sync across different devices, Notes on the Mac supports more formatting, embedded images, and even file attachments. Since Stickies is gone, you can now “pin” a note to the Desktop. And yes, you can choose any font you want.

Since Notes on iOS doesn’t yet support this additional formatting, Apple “translates” the notes so they look appropriate on the smaller device. When I added an image, Notes didn’t display it on my iPhone, but I did see an icon that indicated there was an attachment.

Reminders also comes to the Mac and maintains nearly the same features as on iOS, minus location-based reminders. Both Notes and Reminders can work with CalDAV to support services other than iCloud.

Unified Messaging — Goodbye iChat, hello Messages! According to Apple, over 100 million Messages users have sent 26 billion messages using iMessage on iOS. Messages completely overhauls iChat and unifies it with the FaceTime video chat app and the Messages text messaging app on iOS. And Messages is now available in beta for Lion users.

Aside from the visual improvements, Messages now completely supports iMessage messages on the Mac. This is unified with your other devices, so if someone sends a message to any of your iMessage email addresses, it will appear on all devices at once. Messages sent directly to your phone number, and not to an email address, appear only on your iPhone. You can send any attachment up to 100 MB, including video. All messages are encrypted from end-to-end.

Messages also supports group messaging, plus all the features of iChat. I was a bit worried that Screen Sharing would be gone (since that’s the only way I can keep certain family members online), but fortunately it’s still there.

Of all the changes, Messages hammered home to me the power of bouncing between devices without having to think about it. In one day, I tested it across my iPhone, iPad, and Mac, all without caring what was on or off, which app was open or closed. I merely moved from device to device while maintaining a continual conversation. It doesn’t matter if someone is on an iPhone or a Mac — I can message them, FaceTime them, and exchange files. That’s just a small example of the power of the cloud.

Gaming Gets a Power Up — One of the most compelling demonstrations during Apple’s briefing was watching a head-to-head real-time race in Real Racing 2, with one user on a Mac, the other on an iPad, and the Mac streaming to a high-definition television.

Mountain Lion brings the iOS Game Center to the Mac. Aside from its social features, like finding friends and leaderboards, Game Center adds voice chat, status synchronization, notifications, and cross-platform multiplayer gaming. If your game supports it, you can hop off your iPhone and onto your Mac and pick up right where you left off.

And while it isn’t limited to gaming, the new AirPlay Mirroring in Mountain Lion means you can blast your achievements onto the big screen in 720p high definition. When sending to an Apple TV, AirPlay Mirroring will match your Mac’s display resolution, or you can set your Mac’s resolution to match the TV. (I was unable to test this, as AirPlay Mirroring informed me that my Apple TV wasn’t running the right software version.)

As a professional speaker, I find AirPlay Mirroring from a Mac to a TV interesting, but I would rather send from my iOS device to my Mac, which I would then connect to a conference projector. Then I could wander the stage while writing notes and drawing diagrams from the iPad onto the big screen.

Gatekeeper — Gatekeeper is a significant advance in the history of Mac security. Admittedly, I’m somewhat biased since security is my day job.

Nothing can prevent malware from being written, but Gatekeeper should ensure that we never see a Mac malware epidemic. It limits the kind of downloaded applications that will run on your Mac. It’s an extension of the File Quarantine feature first introduced in 10.5 Leopard, and it enables you to limit applications to those that come from the Mac App Store, or a combination of the Mac App Store and identified developers who sign their applications with a digital certificate issued by Apple. For Mac users who want to avoid Trojan horses and other malicious downloads, Gatekeeper is a compelling security option. I’ve written a detailed description of Gatekeeper in “Gatekeeper Slams

the Door on Mac Malware Epidemics” (16 February 2012).

The Future is the (i)Cloud — Although a lot of the early coverage of Mountain Lion will focus on the influence of iOS on OS X, the real story is the growing role of iCloud. iCloud is the glue holding the Apple ecosystem together. Increasingly, Mac users’ settings, data, and communications are stored and managed in iCloud. In “The Future Is Disposable” (24 June 2011), I wrote:

Many vendors offer tools to host files and backups in the cloud, but Apple is taking iCloud in a totally different direction. Within Apple’s ecosystem the cloud becomes the center of everything — your apps, your data, and your settings. It won’t be done by file synchronization that extends our current model of computing, but by baking the concept of cloud access into everything we do at a fundamental level. Our devices finally become tools, not roach motels where the bits check in, but never check out.

If Apple pulls this off it will be one of the most ambitious leaps in the history of consumer technology. Just as the Mac changed desktop computing, the iPod changed the way we listen to music, and the iPhone transformed the mobile phone into something from science fiction, the overlap of iCloud, Lion, and iOS could change everything we know about personal computing.

Mountain Lion is the clearest indication yet that Apple shares this vision. If they succeed, how we use our computers, tablets, phones, and perhaps even televisions will never be the same.

Gatekeeper Slams the Door on Mac Malware Epidemics

There are three ways to attack a computer — gain physical access, hit it over the network, or trick the user into running something they shouldn’t. Macs are reasonably well protected against two of the three.

If you use a strong password and encrypt your hard disk using FileVault, only a sophisticated attacker can get in. Up-to-date Macs are reasonably secure against direct network attacks, and when vulnerabilities do crop up, a combination of anti-exploitation features makes it a lot harder for the bad guys (at least on Mac OS X 10.7 Lion). So for physical and network attacks, we Mac users are in pretty good shape.

But the third kind of attack? Well that’s a bit of a problem, since we humans, even the most paranoid of us, can fall prey to trickery. It’s a problem we haven’t had very good solutions for… until now.

OS X 10.8 Mountain Lion includes a transformative security technology called Gatekeeper. It’s a major new advance in operating system security designed to reduce dramatically the ability of an attacker to trick users into installing malicious software. It could be the key to preventing a future malware epidemic.

We Are the Weakest Link — I used to tell people they were safe as long as they stayed out of the shadowy neighborhoods of the Internet, but danger is everywhere these days. Attackers know that even the most paranoid of us can’t identify every possible threat, and they use sophisticated techniques to trick us into running malicious software on our computers.

We haven’t had a lot of good ways to protect ourselves from nasty downloads. Both Mac OS X and Windows maintain blacklists of known malware and throw up warnings in our browsers in an attempt to prevent us from downloading dangerous things, or at least to alert us when we do. Third-party antivirus tools extend the blacklist approach as far as is reasonable, with vast libraries of bad things to block, but that race is one that the good guys can never win, given that there are now tens of thousands (really!) of new malicious software variants appearing every day.

In fact, there are so many new bad pieces of software appearing daily that most enterprise-level antivirus vendors are taking the opposite approach and offering whitelist tools that allow only approved software to run, thus locking down desktops tighter than a supermax prison. That can work in a business environment, but it’s totally unrealistic for home users.

After all, the rest of us install software all the time, from all sorts of places. We download it from trusted sources like the Mac App Store and our favorite vendors, but many of us still sometimes grab tools from unfamiliar locations. Even when we try to download only from trusted locations, the bad guys have become masterful at deceiving us into running software that we sometimes don’t even know is a program.

This is why iOS has so many fewer security problems than Android or any general-purpose operating system. Users can download apps only from the App Store (without jailbreaking, of course, which itself requires exploitation of security vulnerabilities). Those apps are locked into their own private sandboxes and given at least a cursory review by Apple. The system isn’t perfect (notably due to the impact the approval process has on the overwhelming majority of developers who are legitimate), but has so far prevented any widespread malicious software. Thanks to its more-open model, Android suffers far more security attacks (researchers recently discovered an Android-based botnet comprising more than 100,000 devices). Some Android and Symbian users now install antivirus software on their phones.

The Mac App Store provides an iOS-like experience for Mac users in terms of safety, albeit with fewer application restrictions. Software is reviewed and is easy to revoke should something slip through. Starting 1 March 2012, all new apps must be sandboxed to reduce the damage they can do to your Mac if they are malicious or introduce a new security vulnerability. But while the Mac App Store is far safer source than the big bad Internet, there’s nothing to stop us from installing software from other locations, as there is on iOS. And considering all the Mac App Store restrictions, we’ll likely never see a day where we want Apple as the final arbiter for all software we run on our Macs.

That’s where Gatekeeper comes in.

Gatekeeper Changes the Game — Gatekeeper is a new feature of OS X 10.8 Mountain Lion that is designed to provide Macs with the security of iOS, while still accounting for the different ways we use Macs. Gatekeeper wraps together a string of technologies Apple began introducing over the past few versions of Mac OS X, the Mac App Store, and a new credential Apple will provide developers (for free).

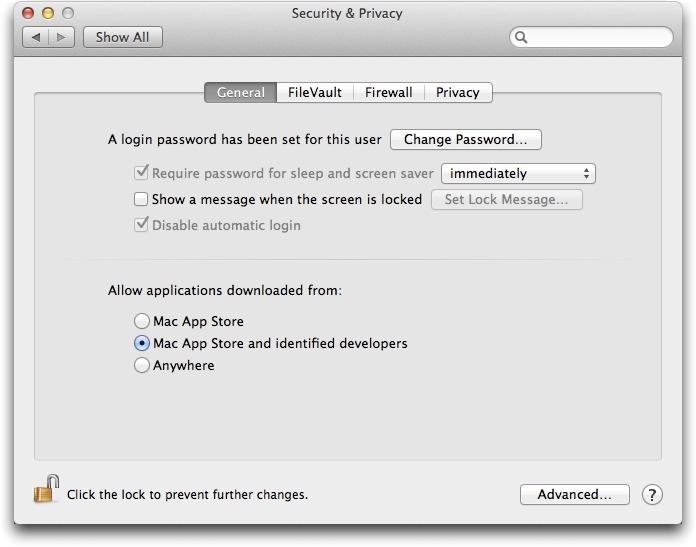

You interact with Gatekeeper via a new setting in the Security pane of System Preferences that enables you to restrict what applications you allow to run, based on where you downloaded them from:

- Mac App Store: These applications are reviewed by Apple, use sandboxing (or will, by the time Mountain Lion is released), and the code is digitally signed so OS X can detect if it has been modified by malware.

-

Mac App Store and identified developers: Beginning immediately, Apple will start issuing digital certificates to developers registered in the Apple Developer Program. Developers can use these certificates to sign applications they distribute themselves. These applications aren’t reviewed by Apple, but if malicious activity is detected Apple can revoke a certificate and block future installations from that developer.

-

Anywhere: Full freedom to run whatever code you want.

No matter which of the three options you pick, you can manually allow any application to run. Apple has provided a well-designed user interface to prevent mistakes and mindless click-throughs, so it will probably be best to stick with the second option (Mac App Store and identified developers), and allow other applications to run only if you’re absolutely certain they’re safe.

For the first time, we have a tool built into OS X to protect us — at least those of us who want or need it — from ourselves. Gatekeeper dramatically reduces the likelihood of Mac users, particularly those who don’t have the sophistication or knowledge necessary to make informed decisions, installing malicious applications.

To provide complete coverage, Gatekeeper combines lightweight whitelisting, a smidgen of anti-malware blacklisting, and two options for how software can be trusted. Let’s look at each of these in turn.

How Gatekeeper Works — Building on the File Quarantine feature first added in 10.5 Leopard, Gatekeeper checks every downloaded application before it runs for the first time. It allows applications to run only if they match your settings, haven’t been tampered with (assuming they’ve been digitally signed), and are free of known malware on Apple’s list.

This last bit is the smidgen of anti-malware blacklisting I mentioned; not much has changed here, but it makes sense for Apple to be able to identify the most prevalent and troublesome pieces of malware automatically.

Gatekeeper’s whitelisting is the polar opposite of how most consumer-level antivirus tools work. Instead of trying to prevent problems using a blacklist of known bad things, whitelisting allows only those things that we have a reasonable assurance are good. In other words, Gatekeeper is a step in the direction of the draconian whitelisting approach used by enterprise-level antivirus companies, but one that maintains the usability required by home users who shouldn’t be restricted to a short list of accepted software.

And the key to whitelisting, which Apple can get away with more than any other operating system vendor, thanks to its tight controls on development, are the combination of a trusted software repository in the Mac App Store and identification of trusted developers via digital signatures.

At Gatekeeper’s strictest setting, you can install downloaded applications only from the Mac App Store. These are the most trusted applications since they have been manually reviewed by Apple, implement sandboxing, and use code signing. That doesn’t mean something bad can’t slip through the cracks, but if it does, the odds are high it will be detected, reported to Apple, and pulled from the Mac App Store. The app will still be on your system, although Apple could potentially clean it out with a security update as they did for MacDefender last year (see “Security Update 2011-003 Addresses MacDefender Malware,” 31 May 2011).

In the middle setting, you can also install applications from identified developers. This code isn’t reviewed or sandboxed, but it is code-signed to eliminate the possibility of tampering after the fact. Since Apple Developer IDs tie back to a registered member of the Apple Developer Program, there is also some attribution if a malicious application is issued, and, once it has been discovered, Apple can immediately blacklist that digital certificate to protect the rest of the user population. Again, I’m sure we will see someone game the system and issue malicious applications, but the chances of this happening at scale are much lower than before. (Your local certificate blacklist is updated once a day.)

Finally, there’s still a manual process to install whatever you want, whenever you want, no matter what you have set. These applications still undergo the malware blacklist check to help catch the most common bad stuff.

One of the most important aspects of Gatekeeper is its user interface. Once you pick a setting, you won’t be plagued with alerts unless you try to install something that violates your settings. If you do try to install software from an untrusted source, the alert doesn’t give you the option to click through and install it anyway. Clicking without reading (or understanding an alert) is a serious security design flaw, so eliminating that option dramatically increases Gatekeeper’s efficacy and value.

If you still want to install an application, you must Control-click it and manually enable it from a contextual menu. (Apple warned me that my test system uses a different workflow than the official preview release so I can’t show you the exact process.)

Many of us assumed that Apple would some day offer an option to allow installation of only Mac App Store applications to improve the security of average users. When I talked with other press and security experts, I even said I was looking forward to the feature, especially for friends and family who rarely run complex software. However, such a requirement would hurt developers whose software simply can’t meet Mac App Store sandboxing requirements, or who don’t want to sell through the Mac App Store. The addition of the Developer ID option directly addresses that concern and provides a nice balance of flexibility and control.

There are still some areas where Gatekeeper doesn’t help. It doesn’t check applications on CDs or DVDs, USB drives, or other physical media attached to the Mac. It evaluates only downloaded applications. Also, Gatekeeper checks only complete executable applications, so it won’t protect you from a malicious Flash game or Java applet that runs in your Web browser (although Macs ship with both disabled by default).

Why Gatekeeper Matters — Right now the single biggest source of malicious software on Macs is Trojan horse programs. Even on current versions of Windows (Windows Vista and Windows 7), we see far fewer self-replicating viruses. Thanks to the anti-exploitation features we first saw in Windows and that have now become standard in Mac OS X, modern operating systems are far harder to exploit than even a few years ago. It happens, but it takes a lot more skill, and it’s far easier to trick unsuspecting users instead.

As I wrote a year ago in “Apple’s Security Past Defines Its Future” (27 January 2011), our biggest security risk as consumers is the increasing sophistication of the techniques attackers use to trick us into hurting ourselves. While our operating system vendors can’t do much to prevent us from emailing our financial data directly to the bad guys, or handing over our usernames and passwords to convincing fake Web sites, they can make it a lot harder for attackers to take over our computers.

That’s where Gatekeeper comes in. While I’m sure attackers will figure out ways around it, or new ways to trick us into installing evil software, Gatekeeper makes it a heck of a lot harder for them to do anything widespread. Gatekeeper reduces attackers’ ability to automate, increases the cost of attacks, and thus reduces their economic advantages (and believe me, the main reason malware still exists is because of the money that can be stolen or earned). We will still see malware, but Gatekeeper, in conjunction with the rest of OS X’s security features, dramatically reduces the likelihood that we will see malware that affects more than a small number of users.

At some point, maybe even someday soon, someone will upload a malicious app to the Mac App Store or slip some nefarious app signed with a Developer ID onto the Internet and the media will froth and proclaim the end of innocence.

But it won’t matter. Because every attack that ends up in the headlines is an attack thwarted. And behind the media furor we’ll see a string of one-off stories, but no epidemic.

I’ve written up some more technical details on Gatekeeper at Securosis.com.

TidBITS Watchlist: Notable Software Updates for 20 February 2012

Default Folder X 4.4.9 — St. Clair Software has released Default Folder X 4.4.9, whose marquee change is the capability to add favorite folders via a contextual menu in the Finder. This new release of the popular Open and Save dialog enhancement utility now also supports Automator workflows in Mac OS X 10.7 Lion and will support the next version of Automatic Duck’s Pro Import AE plug-in for After Effects. The update is rounded out by a number of fixes, including a bug that caused applications (notably Sandvox) to crash when they opened URLs, and a problem with Default Folder X forgetting favorite folders on some

networked drives. ($34.95 new, $10 off for TidBITS members, free update, 10.6 MB, release notes)

Read/post comments about Default Folder X 4.4.9.

VLC 2.0 — VideoLAN has released VLC 2.0 (nicknamed Twoflower), a major release for the free, open-source multimedia framework and player that offers wide support for various video formats. At the user interface level, the new release moves to a completely overhauled single-window design. Under the hood, the update provides faster decoding on multi-core processors, improved decoding for MKV and MOV formats, additional codec compatibility (including ProRes and AVC/Intra), and improved subtitle rendering to better fit the displayed window. It also offers support for Blu-ray playback (though this is noted as “experimental”).

View a lengthy list of features and format compatibility on VideoLAN’s Web site. (Free, 24 MB)

Read/post comments about VLC 2.0.

Bookle 1.0.4 — Stairways Software has released Bookle 1.0.4, the EPUB reader for the Mac that was developed in collaboration between TidBITS’s Adam Engst and Peter Lewis of Stairways Software (see “Introducing Bookle, an EPUB Reader for Mac OS X,” 6 February 2012). This update fixes a small glitch with the initial selection of some books, expands the range of the font size selection to 160 point for those who want really large font sizes, and adds support for invalid EPUBs with unencoded spaces in their table-of-contents references. The new release also defaults to UTF-8 to

fix some character display issues and adds tips to the toolbars for better VoiceOver support. ($9.99 new from the Mac App Store, free update, 2.6 MB)

Read/post comments about Bookle 1.0.4.

Airfoil 4.6.5 — Rogue Amoeba has released Airfoil 4.6.5, which updates the popular network audio streaming app for the Mac with both new and restored features. As with other recent Rogue Amoeba updates, it includes the latest version of the Instant On component (5.0), which can now capture audio from sandboxed applications purchased from the Mac App Store. Plus, Airfoil Speakers can now remotely control playback from several new sources, including Pandoras Box, Musicality, Muse, and Muse Controller’s Pandora player. The update brings back compatibility with capturing video from Netflix in full-screen mode, and also

restores compatibility with Apple Remote and Keyspan remotes in Mac OS X 10.7 Lion. Other updates include the capability to configure pulled audio from input devices in Audio MIDI Setup and the use of the Apple Lossless encoder/decoder for improved audio compression. ($25 new, free update, 9.8 MB, release notes)

Read/post comments about Airfoil 4.6.5.

ExtraBITS for 20 February 2012

Interesting bits this week include a look at the new iTunes U, another Tech Night Owl podcast for Adam, Apple’s latest insane app rejection, video of a “Parenting in the Mobile Internet Age” panel from Macworld | iWorld, a humorous look at the downsides of ebooks, and Glenn’s explanation of why the recent security flap about insecure keys isn’t that concerning for readers.

Driving the Classroom with iTunes U — Fraser Speirs digs deep into iTunes U now that the service has graduated beyond offering free iTunes Store lectures to its own iOS app. Speirs teaches at a private school in Scotland, and is an Apple Distinguished Educator whose schedule has lately been packed with travel and speaking engagements related to how he’s implemented a program that provides an iPad for every pupil.

Bookle, Apple’s Bugs, and the Paperless Office on the Tech Night Owl Live — Adam once again joins host Gene Steinberg on the Tech Night Owl Live to discuss the release of Bookle, the problems Apple has had with Security Update 2012-001 and Mac OS X 10.7.3, and how the iPad may finally be ushering in the age of the paperless office.

Air Dictate 2.0: Latest Insane App Store Rejection — The story so far: Avatron created the Air Dictate app to use the iPhone 4S’s speech dictation for dictating into apps running on your Mac. After initially approving it, Apple pulled the 1.0 version from the App Store, citing Avatron’s use of a non-public method of invoking Siri, so Avatron revised Air Dictate 2.0 to eliminate that interface approach. Now Apple is rejecting the app for lack of compliance with Apple’s trademark guidelines, despite the fact that the app nowhere uses the word “Siri,” the Siri icon, or anything other

than the standard iOS interface of starting dictation when you raise the iPhone to your ear.

MacVoicesTV Parenting Panel from Macworld | iWorld — Tonya Engst discusses raising children in the age of screentime as part of the “Parenting in the Mobile Internet Age” panel discussion from Macworld | iWorld 2012, moderated by Chuck Joiner of MacVoicesTV.

The Unexpected Downsides of Ebooks — With tongue firmly in cheek, Cracked (yes, Cracked) delves into the pitfalls of our societal move away from printed books to ebooks on iPads and Kindles — from no longer having an extra support for your IKEA bed to the declining impact of book burnings.

Web Certificate Flaw Not Dangerous — Two sets of researchers revealed that insufficiently random choices of the prime numbers from which encryption keys are derived for Web site SSL/TLS certificates mean that the private parts of the keys can be derived. Fortunately, it’s not a flaw in an algorithm, and seems to affect only a small number of sites. Read the whole explanation in Glenn Fleishman’s account at Boing Boing.