TidBITS#1131/25-Jun-2012

It’s a potpourri of topics this week, anchored by Security Editor Rich Mogull’s extensive Q&A about sandboxing, the Mac App Store, and Gatekeeper. Also timely are Adam Engst’s explanation of how to sync iCloud contacts on pre-Lion Macs using SOHO Organizer, his followup on Apple’s fix to the damaging Thunderbolt Software Update 1.2, and Agen Schmitz’s roundup of reviews of the MacBook Pro with Retina Display. Tossing timeliness to the winds, Michael Cohen contributes a look back at a 1982 New York Times article summarizing a remarkably prescient NSF-commissioned report on the future of communications and computing. Notable software releases this week include TextExpander 4.0, Skype 5.8.0.865, and Bento 4.1.1.

Thunderbolt Software Update 1.2.1 Released, Apple Apologizes

Apple has, with no change in the release notes, released Thunderbolt Software Update 1.2.1 to add support for the Thunderbolt to Gigabit Ethernet Adapter. Version 1.2 of the update was notable for causing boot failures, and although the assumption is that Apple addressed the problems, we won’t know for sure until reports start to come in from users (see “Thunderbolt Software Update 1.2 Causes Boot Failures,” 12 June 2012). Happily — and unusually — Apple has acknowledged the problems caused by version 1.2 of the update, apologized for the disruption, and offered recovery

information.

Although it will reduce the sample size of fresh installations, I cannot recommend that you install this update unless you have and need to use the Thunderbolt to Gigabit Ethernet Adapter for your MacBook Air or MacBook Pro with Retina Display (the device should work on any Thunderbolt-equipped Mac, but all other models should have a dedicated Ethernet jack). At least with what Apple is telling us in the release notes, the update has no other benefits.

While I don’t wish to denigrate what Apple has done here in terms of acknowledging the problem in public and apologizing for the disruption, since that’s such a refreshing change, I would like to point out that it took Apple several days to remove Thunderbolt Software Update 1.2 from distribution, during which time tens of thousands of Mac users could have wasted one or more hours each reinstalling Mac OS X. During those days, the word spread quickly via TidBITS and other Mac media sites, and via social networking, and although there’s no way to know how many people would have been affected, it’s likely a non-trivial number. In this day and age where the media appears to focus on rumors and controversy, this is an excellent

example of the true value of an independent technology press.

MacBook Pro with Retina Display: Review Revue

Bandying about superlatives ranging from “groundbreaking” to “jaw-dropping,” early reviewers of the recently released MacBook Pro with Retina Display (see “New MacBook Pro Features Retina Display, Flash Memory,” 11 June 2012) seem to have avoided the comedown that many experience after a showy Apple introduction, and are quite smitten overall with this update to an Apple classic. This praise is forthcoming despite the fact that many aspects of the new MacBook Pro — from the high-resolution Retina display to use of flash memory storage to quicken the overall user experience — are far more evolutionary than revolutionary (see “Incremental Change Wins Apple Big Gains,” 29 March 2012, for Glenn Fleishman’s treatise on the relative modesty of most Apple hardware upgrades).

Here at TidBITS, the only staff member who received a review unit was Jeff Carlson. Unfortunately, he was beholden to one of his other gigs (a little rag called the Seattle Times) for a hands-on review, so let’s swing around the Internet to see what he and some other reviewers are saying.

On the subject of the new MacBook Pro’s centerpiece feature — the 15.4-inch Retina display with a resolution of 2880 by 1800 pixels — Roman Loyola at Macworld writes that photo details and text were amazingly crisp when he set the MacBook Pro to its Best (Retina) resolution setting. But he also found himself giddy over reading system alerts: “The Retina MacBook Pro helped rekindle my appreciation for the little details of Mac OS X that, over time, I’ve taken for granted.”

The one downside of having so many pixels (5.184 million, to be exact, at 220 pixels per inch) is that software not optimized for the Retina display (such as Adobe InDesign and Twitter, two examples offered by reviewers) will render images and text poorly. But for MG Siegler at TechCrunch, the biggest problem with the Retina display is the lackluster rendering of text and images in Web browsers — not just those that haven’t yet been updated for the display (such as Google Chrome, which has Retina support under development) but also in the Retina-optimized Safari. He writes:

“If you want examples of apps that look brilliant with the retina display, try any of Apple’s (iPhoto, iMovie, etc). Or visit apple.com from Safari. Otherwise, things are fairly bleak at the moment. And the reality is that depending on how graphic-heavy the app/site is, it’s going to be a lot of work for developers to make the upgrades.”

Speaking of selecting the Retina setting for optimized viewing on this pixel-packed display, Tim Stevens at Engadget complains that there isn’t a way to choose an explicit numerical resolution setting. Instead, the Display preference pane presents you with a five-position slider that ranges from Larger Text on one end of the spectrum to More Space on the other, with Best (Retina) sitting in the middle. “It’s perhaps more friendly for novice users,” he writes, “but remember: this is a laptop with the word ‘Pro’ in the name.” (And if you don’t believe that, consider that it can run four displays at their native resolutions.)

In his Seattle Times review, Jeff Carlson is certainly impressed by the screen’s resolution and notes that it’s “still glossy, but not as reflective as the standard MacBook Pro screen, which is a big improvement.”

However, the Retina display isn’t the standout feature of the new MacBook Pro for Jeff, due largely to the fact that he works most of the time tethered to an external monitor at his desk. Rather, it’s the breakneck speed of the machine. Thanks to the combination of the 2.3 GHz Intel Core i7 processor in his review unit and the solid-state drive, Jeff was able to open Adobe InDesign in just 3 seconds (compared to 25 seconds on his 2-year-old MacBook Pro).

For those looking to be more mobile, Engadget performed its battery rundown test and got 7 hours, 49 minutes with the 2.6 GHz Core i7 model and 9 hours, 22 minutes for the 2.3 GHz Core i7 version — which compares favorably to the 7 hours of battery life claimed by Apple. However, Katherine Boehret at All Things D put the MacBook Pro through her “standard battery test,” which seems to stress the laptop more than your typical user by maxing out screen brightness, turning off all power-saving features, playing an endless loop of music, and keeping both

Wi-Fi and email retrieval on. Boehret averaged just over 4 hours of battery life from this test (performed twice), though she believes the MacBook Pro would be more likely to see over 5 hours of battery life under less stressed conditions.

Mark Spoonauer at Laptop Magazine found that the new asymmetrically spaced fans on the Retina MacBook Pro definitely help keep the noise level down while the laptop is handling processor-intensive tasks (such as editing HD video). However, the heat levels coming out from the keyboard were “well above what we consider uncomfortable” at 105 degrees Fahrenheit (40.5 degrees C); the touchpad and the bottom of the laptop were cooler.

From a gaming perspective, Ross Miller at The Verge tested Diablo 3 on the new MacBook Pro with a 2.6 GHz Core i7 processor and 8 GB of RAM, running the game at maximum resolution and pushing “the game’s eye candy to the max” (shadows, special effects, etc.). He found that the game “jumped between 15 and 20 frames per second — just barely playable at most times,” but that bringing the resolution down to 1680 by 1050 (the resolution of the standard MacBook Pro) helped provide a consistent 30 frames per second for better playability.

Be sure to check out The Verge’s typically gorgeous and fast-paced video review of the Retina MacBook Pro, where Miller’s summary echoes many of the other reviewers’ sentiments:

“The new MacBook Pro with Retina Display really is kind of the culmination of everything Apple has learned in the MacBook field. Granted, of course, it is the most expensive MacBook Pro out there, one of the most expensive laptops out there. But, if budget’s not an issue, this is the best laptop you can buy right now.”

SOHO Organizer Syncs Contacts with iCloud in Snow Leopard

As the MobileMe sunset date of 30 June 2012 draws ever closer, people continue to look for ways to integrate Macs running Mac OS X 10.6 Snow Leopard into the iCloud ecosystem. Despite the fact that Apple based iCloud on standards like CalDAV and CardDAV, this hasn’t been entirely trivial. With calendars, we’ve written about two solutions: BusyCal (“BusyCal Brings iCloud Calendars to Snow Leopard,” 5 December 2011) and iCal (“iCal in Snow Leopard Can Participate in iCloud,” 11 December 2011). But good solutions for syncing contacts with iCloud have been harder to find, since the tricks that worked with pointing iCal at iCloud failed

with Address Book.

Happily for those who have perfectly functional Macs still running Snow Leopard, for whatever reason, we’ve come across a way of syncing contacts with iCloud. It’s not free, but it is easy — the $99 SOHO Organizer 9 from Chronos. This capability is relatively new to SOHO Organizer, appearing in version 9.1.8, but Chronos has been refining it since introduction — the current version is 9.2.6. In fact, SOHO Organizer requires only Mac OS X 10.5.8 or later, making it useful for anyone who wants to access iCloud contacts on a Mac that can run any version of Mac OS X from 10.5 Leopard to 10.7 Lion (and, we presume, but have not tested, 10.8 Mountain Lion).

SOHO Organizer is actually a three-application suite consisting of SOHO Organizer, which offers contact and calendar management; SOHO Notes, a note-taking and snippet-keeping utility; and SOHO Print Essentials, which helps you design and print labels, envelopes, letterhead, and so on, importing data as necessary from SOHO Organizer. I won’t be talking about SOHO Notes or SOHO Print Essentials — they seem to be effective programs, but are out of scope for this article.

I also won’t discuss SOHO Organizer’s calendar features, but suffice to say that it is actually a third solution to the iCloud calendar syncing problem, since it, like BusyCal, can sync with iCloud (and Google Calendar). From what I can see, SOHO Organizer offers basically the same feature set as BusyCal and iCal — if I were buying SOHO Organizer first, I would see if it met my needs before buying BusyCal, but since I’m already a happy BusyCal user, I haven’t seen the need to explore SOHO Organizer’s calendaring features much.

And as a final caveat, I’m assuming that you have already converted your MobileMe account to iCloud and are merely trying to gain access to your iCloud contacts on a Mac running Snow Leopard. If you need help making that conversion, run, don’t walk, to get a copy of Joe Kissell’s “Take Control of iCloud,” which explains in detail what’s involved.

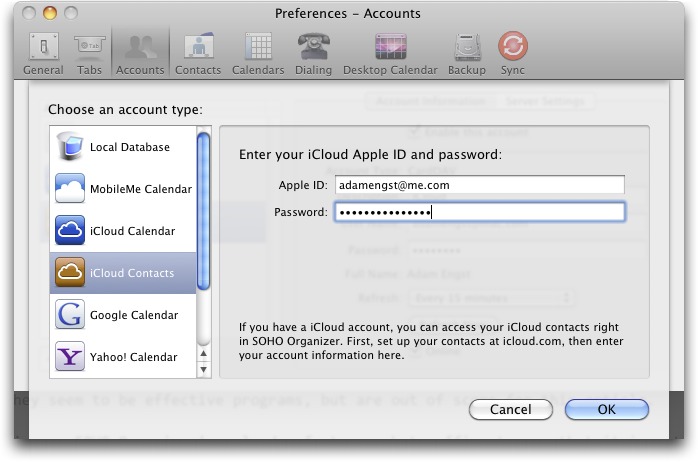

Setting Up and Using SOHO Organizer for Contacts — Despite the many other capabilities of the SOHO Organizer suite, setting it up for syncing contacts with iCloud is trivially easy. All you have to do is open the Preferences window, click Accounts, click the + button to add an account, choose iCloud Contacts, and enter your iCloud user name (as a full email address) and password. SOHO Organizer fills in the rest of the details behind the scenes, makes the connection, and downloads all your contacts.

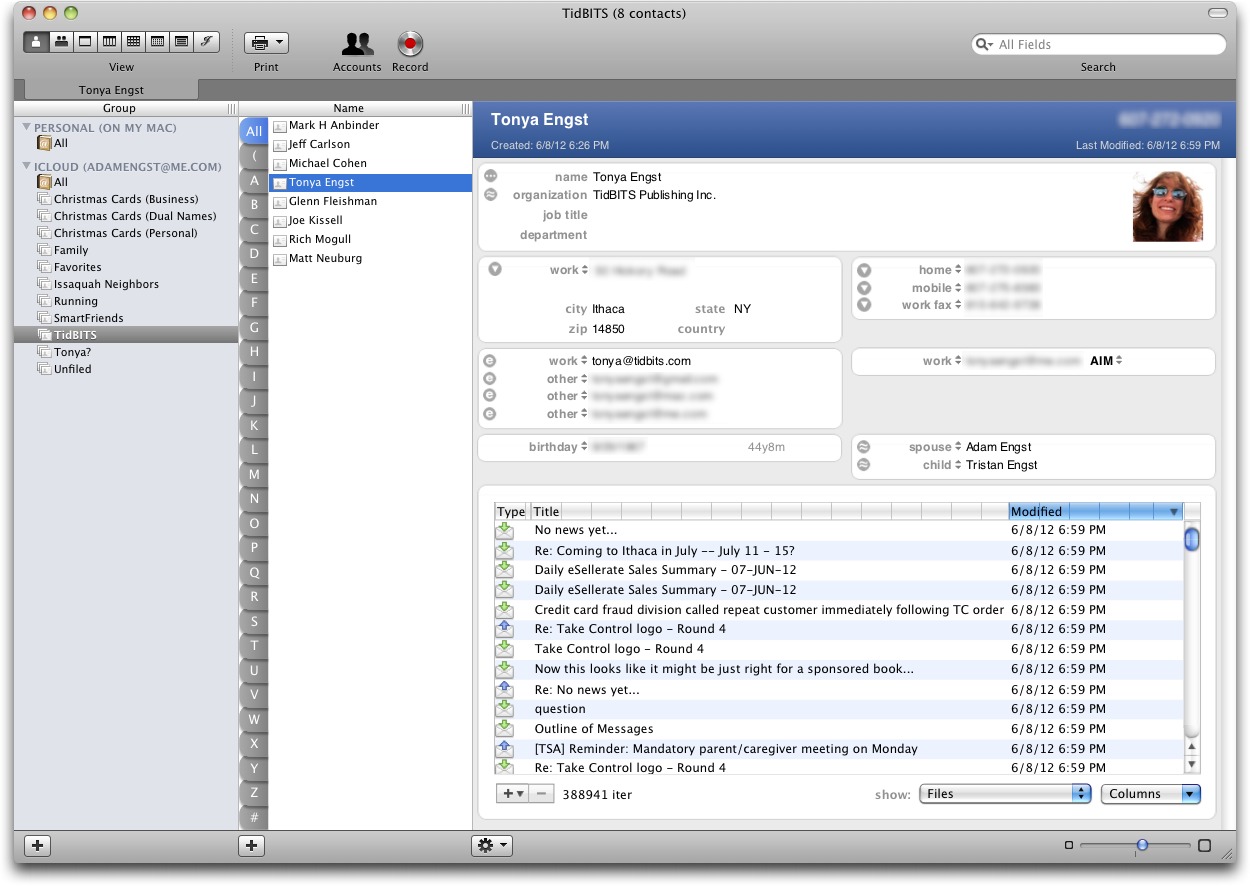

I’ve never been a fan of Address Book in general, and I hate the leatherette version in Lion with a passion, so I find SOHO Organizer’s approach to displaying contact information refreshingly complete and usable. A series of buttons in the upper-left of the window let you switch between contact (the first two), calendar (the next five), and journal (the last one) views. The Contact Card view shows detailed information for a single contact that you display by selecting a group and then a name in the first

two columns. The data includes everything you’d expect, in terms of name, address, phone numbers, email addresses, instant messaging accounts, birthday, and relationships, and an attachment block that can contain a list of email messages to and from that person, along with phone calls, text messages, calendar events, notes, files, and more. You can add some additional blocks, such as for URLs, more addresses, notes, and so on. Plus, you can even switch to an expanded version of the name block, which adds fields for prefix, suffix, middle name, nickname, job title, department, phonetic names, and maiden name.

Much of this data is “live,” in the sense that you can click a little icon next to an email address to create a new message to that address, and clicking the icon next to a spouse or child name switches to that person’s card. Other actions include mapping an address, calling a phone number, and sending an SMS message. You can also double-click email messages and other items in the attachment list to open them.

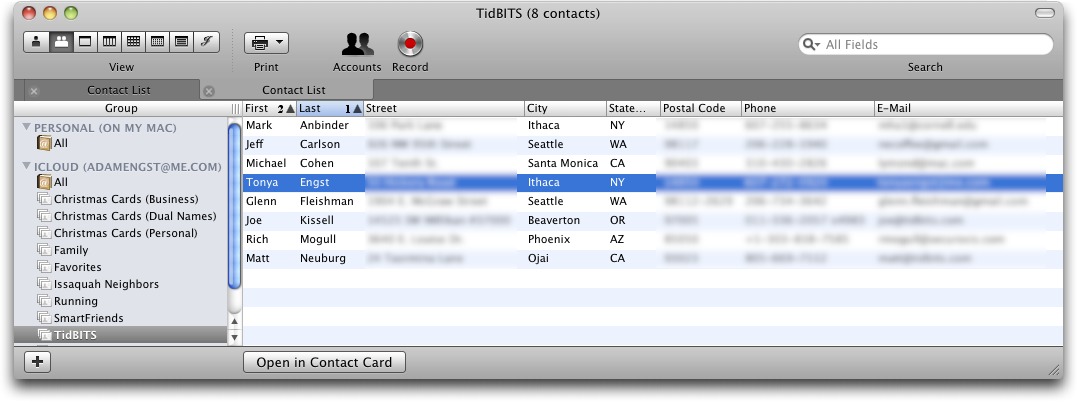

Along with the Contact Card view, there’s Contact List view, which displays all the contacts in a particular group in a scrolling list, with numerous columns available; you choose which to display from View > Contact List Columns, and you can rearrange them by dragging, resize them, and sort them (Shift-click for a secondary sort, such as Last Name, then First Name). Double-clicking data in a list item lets you edit it directly, and you can click the Open in Contact Card button to switch to the detailed Contact Card view.

SOHO Organizer has a few other niceties related to contacts. You can search for duplicate cards and information within cards. It’s easy to merge cards, with a nice display of the differences. You can also create bidirectional relationships between people by dragging one person’s card onto another; this enables you to identify someone as another person’s spouse, child, manager, assistant, and so on. For faster navigation in Contact Card view, SOHO Organizer offers an Alphabet Bar that lets you jump quickly

to contacts whose last names start with a particular letter. Lastly, you can open multiple windows so you can see both Contact List and Contact Card views simultaneously, or just multiple cards.

The main negative I see with SOHO Organizer and its traditional approach to contact management is that it has no concept of connecting to Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, or other social networking services, as does the recently released Cobook (see “Cobook 1.0,” 25 May 2012). I also experienced a few performance issues on (only) one of my test Macs, though they may have been related to specific zoom levels or database corruption that was resolved by starting over; Chronos was extremely responsive to my reports, and version 9.2.7 should be available shortly with minor changes.

No Link to Address Book — Despite SOHO Organizer working perfectly with iCloud-hosted contacts, bringing in and sending out changes appropriately, there’s one major limitation for those running under Leopard or Snow Leopard that may not be obvious up front, but which could be a deal-breaker. The contacts that SOHO Organizer retrieves from and syncs with iCloud appear in an iCloud collection in the sidebar, and only there. That’s all that’s necessary for people running under Lion.

But what if you want to access those contacts in the Leopard or Snow Leopard version of Address Book, or in another program like Cobook or Apple Mail that shares Address Book’s data store in a pre-Lion system? There, unfortunately, your luck has deserted you. SOHO Organizer has another collection in the sidebar — Personal (On My Mac) — and any contacts in there do use Snow Leopard’s Sync Services to sync with Address Book and all other Address Book-aware programs.

You can select all your contacts in the iCloud collection and drag them into the Personal (On My Mac) group to copy them over, at which point they will appear in Address Book (beware that corruption in field labels can prevent syncing — if this happens to you, sync smaller groups at a time to find the problematic contact). That will give you read access to those contacts, but what you can’t do is make changes and have them sync back to the iCloud collection in any way. I tried dragging them back from Personal (On My Mac) to iCloud, but that tended to result in the iCloud version of the contact being corrupted or deleted. Even if it had worked, it’s an unsatisfactory solution, since it would require both manual

copying of cards and then a lot of manual verification of data and determining what was old and what was new. That’s what we have synchronization tools for!

Theoretically, Chronos could add the capability to sync between the iCloud and Personal (On My Mac) collections, but given that it’s only of use to people who need this particular hack to access iCloud contacts in Address Book in Snow Leopard, it’s hard to see them justifying the engineering work.

In the end, though, SOHO Organizer is both a fully featured contact management program in its own right (not to mention its other capabilities) and a solution to the iCloud problem for Snow Leopard and Leopard users. That makes it well worth its $99 price. A 30-day trial version is available as a 77.6 MB download.

Comparing 1982’s Future to Today’s Present

In June of 1982, the IBM 5150 (the original IBM PC) had been out for less than a year. The Apple II+ was Apple’s big seller and the original Macintosh was still a year and half away from getting out of that bag. There was no Internet, per se; the word “internet” referred to a loose assemblage of exclusively non-commercial networks, such as ARPANET and MILNET, that used TCP/IP.

Also that month, the New York Times reported on the forthcoming release of a National Science Foundation report, “Teletext and Videotex in the United States,” that forecast how electronic communication technology would affect the United States by the year 1998. The report, as reflected in the New York Times summary, was strikingly accurate about some of the societal effects, even if the technological details were quaintly off-target and missed the move to decentralization of computing.

Teletext and Videotex — The report, which was commissioned by the National Science Foundation and written by John Tydeman of the Institute of the Future in Menlo Park, California, envisioned two types of home systems: a one-way communication system called “teletext” and a two-way system dubbed “videotex.” The bulk of the report focused on the transformative effects of the two-way system, described in the New York Times as being based on the “emerging videotex industry, formed by the marriage of two older technologies, communications and computing.”

Videotex service, delivered through home “terminals,” was seen as being used by 40 percent of U.S. households by the end of the century, its availability driven and subsidized by advertising. In the actual event, those home terminals would turn out to be personal computers, and the videotex service would turn out to be connections through various providers by various means to the Internet and the World Wide Web.

And the comparison with home Internet service? While the report overestimated its home penetration for 1998, reaching only 26.2 percent of homes that year according to U.S. Census data, just two years later the number of Internet-connected homes in the United States had exceeded the 40 percent mark (it’s now above 75 percent).

Control and Content — The report also saw people using videotex systems to tailor and combine the types of information available to them: videotex service subscribers, it said, would “create their own newspapers, design their own curricula, compile their own consumer guides.”

In reality, most people were nowhere near as proactive and organized as the report envisioned: instead, the vast majority of users at the turn of the century went no further than compiling disparate sets of disorganized Web bookmarks, and instead relied upon increasingly sophisticated search engines, such as the then-predominant AltaVista and the just-established Google, to help them “surf” to the information they sought. Arguably, with apps like Flipboard and services like Paper.li, not to mention the vast collection of courses available from iTunes U and Khan Academy, we’re much closer to that prediction.

The report did see a dark side to the widespread use of videotex systems, noting that they would “create new dangers of manipulation or social engineering, either for political or economic gain.” Those who have had their identities phished, responded to an Internet scam, or been hoaxed by a fallacious news report about a non-existent political scandal, can recognize the prescience of this part of the report. Angry Birds, FarmVille, and other such “stupid” games might also be an example of manipulation for economic gain.

The report also saw dangers in how such a system could “carry a stream of information out of the home about the preferences and behavior of its occupants.” Of course, while this forecast capability turned out to reflect accurately the loss of privacy that the Internet era has engendered, much of what was perceived as a danger in 1982 has also become a socially accepted part of the business model of companies like Google, Facebook, and others, which rely upon that information to deliver targeted advertisements to increase efficacy (for both advertisers and viewers).

Transformative Effect Checklist — The availability of videotex services was predicted to lead to a number of changes in home life, business, and politics. Let’s look at some of those predictions:

- The home would double as a place of employment: Check. Work-from-home has become an accepted part of American business practice. Although the number of teleworkers was not staggering at the turn of the century, the numbers have been steadily rising every year: by 2010, according to one recent survey, 20 to 30 million people work occasionally from home, and 15 to 20 million are so-called “road warriors.” Businesses and government offices now regularly offer some form of work-from-home support.

- Home-based shopping: The report saw this as permitting consumers to control manufacturing directly. While that sort of supply-chain control has not yet become common, despite sites like Etsy and the first hints of products created by 3D printing, shopping via the Internet has, indeed, transformed the retail landscape dramatically, thanks to Amazon, eBay, and countless small retailers. Half a check.

-

A shift away from workplace and school socialization and toward electronic interaction: While people haven’t abandoned work and school as opportunities for social interaction, Facebook, Twitter, text messaging, and the plethora of socially enabled apps on mobile devices earn this prediction a great big check.

-

The emergence of a new profession of information brokers and gatekeepers: These have emerged in all sorts of guises and forms, ranging from search engine optimization specialists to information aggregators and data-miners. If you look at a site such as Career Builder, for example, you can see that “information broker” is not only a job category but a big one. So, again, check.

-

The fragmenting of the two-party political system: The report predicted that “[v]ideotex might mean the end of the two-party system, as networks of voters band together to support a variety of slates — maybe hundreds of them.” As things turned out, the two-party system in the United States not only endures but has become increasingly entrenched and polarized. On the other hand, grass-roots movements that make use of information technology to organize, raise funds, and effect change have become a very real, and increasingly vibrant part of the political landscape. This one gets a partial check.

If We’d Only Known — I’m sure, at the time of its publication, that there were those who saw the National Science Foundation’s report as a waste of government money, but, if so, it was an uncannily accurate waste of money. Those who happened to read it, pay attention to it, and develop a long-term business or career strategy based upon its predictions, would have been in a good position to benefit as the changes it predicted largely came to pass.

Sadly, though, it said nothing about flying cars. Aren’t we supposed to have those now?

Answering Questions about Sandboxing, Gatekeeper, and the Mac App Store

Apple is in the midst of a major transition with the Mac platform. As users flock to the Mac, it’s only natural that criminals will follow — that growing market share makes the Mac community a sufficiently lucrative target. But it’s clear Apple recognizes this risk. Taking lessons from the currently malware-free world of iOS, Apple has been enhancing the security of Mac OS X since the release of Mac OS X 10.5 Leopard, slowly at first, and more significantly of late.

Apple’s strategy relies on five technical pillars: enhancing the foundational security of Mac OS X; hardening Safari (Web browsers being the most common avenue of attack today); encouraging apps to use sandboxing techniques to limit attack vectors; keeping the Mac App Store as free of malicious applications as possible; and, with 10.8 Mountain Lion, using Gatekeeper to reduce the ability of attackers to trick users into running downloaded malicious applications.

But we shouldn’t think of this as just an ever-escalating technical battle. Apple’s real goal with these changes, especially with the combination of the Mac App Store, sandboxing, and Gatekeeper, is to disrupt the economics that keep the bad guys in business, rather than fighting a never-ending series of one-off skirmishes.

As Uncle Ben said, “With great power comes great responsibility.” Apple’s moves toward a more-controlled (by Apple) experience on Mac OS X scare some users, and they could be problematic for many developers. The challenge for Cupertino will be to strike, and maintain, the right balance between control and freedom. That is, if they want to maintain the innovative heart that has made the Mac so appealing since 1984.

Let’s take a look at sandboxing, the Mac App Store, and Gatekeeper in particular, since they offer both the most promise for preventing attacks and the most risk for the soul of the Macintosh. I’m organizing this around answers to a series of questions — if you have additional questions, please ask them in the comments.

What is sandboxing? — Practically speaking, sandboxing prevents applications from doing unexpected things to your computer. Sandboxing encompasses a set of techniques to isolate applications and minimize what they can do on your Mac. The idea is that some applications could harm your computer, either deliberately or if an attacker compromises them, and putting these apps in a “sandbox” limits the potential damage. A sandboxed application is allowed to interact with the rest of your computer only through a strict set of rules that specify what actions it can perform. Sandboxing has been around for a long time and is already in use in Mac OS X, Windows, and other

operating systems.

Here’s a simplified explanation of how it works. A normal, non-sandboxed application has full access to everything on your computer, which can include reading and writing files anywhere on the file system, sniffing and sending network traffic, watching everything you type, controlling your camera and microphone, and more. (Technically speaking, the app is limited based on which protection ring it’s running in and what user account is active, but that isn’t important for this discussion.) Even if an app isn’t programmed to use all those capabilities, there is nothing in the operating system to limit what it can do. Thus, one of the most common ways to attack a computer is to find an application with a vulnerability, exploit that

vulnerability to inject malicious code into the application, and then use the application to run the malicious code to perform further actions.

In contrast, a sandboxed application doesn’t run with full access. Instead, it executes inside a restricted container that is isolated from the rest of your Mac. Thus, if an attacker were to exploit a vulnerability in the app and inject malicious code, that code would be limited to the sandbox.

That might work for simple, standalone apps like casual games — Angry Birds could be sandboxed easily. But for more complex programs, sandboxing has some obvious problems, like saving files and accessing the network. To work around this problem, each individual application can be given a set of “entitlements” that allow the app limited access to other parts of your Mac. For example, a fully sandboxed app with no entitlements can save files only into its own directory, but with an entitlement, it can be given permission to save files anywhere in your home folder (which is still safer than the app being able to save a file anywhere on the file system).

iOS apps are heavily sandboxed, which is why apps can’t access each other’s files. iOS offers no entitlement to access shared files other than photos, so we’re forced to copy files from app to app using the Open In command.

This particular limitation in iOS, to be blunt, sacrifices usability for security. But at least most apps in iOS don’t create or manipulate documents (although that’s changing, thanks to the iPad). On the Mac, where far more applications are document-centric, and where the entire user experience revolves around the Finder, such a system would be a major disaster that would immediately drive every professional user to Windows. It would become impossible to use multiple apps to make changes to the same document without making a vast number of copies, and keeping track of which change was in which copy would be a nightmare. As a result, Apple has created more possible entitlements for Mac apps than for iOS apps, but sandboxed apps are

still far more restricted than their non-sandboxed brethren.

The overall goal is the same — to ensure an application can’t do too much damage to your system, either by design or if it’s compromised by an attacker. But since the needs of Mac users are different than the needs of iOS users, it’s hard to figure out the right balance of restrictions and entitlements.

Why is sandboxing so important? — Sandboxing is, to put it lightly, a very big deal. As operating systems have become harder to exploit (believe it or not, it’s pretty hard these days), attackers have started targeting specific applications. We see more attacks against Adobe Acrobat and Flash, Microsoft Office, Java, Web browsers, and QuickTime than we do against Mac OS X and Windows themselves. That’s why, for example, Apple now sandboxes parts of Safari and QuickTime, Google sandboxes Chrome, and Adobe sandboxes Reader and Acrobat (only on Windows).

Take Google Chrome. It is widely considered the most secure Web browser available, due to its heavy use of sandboxing. Chrome even embeds and sandboxes its own version of Adobe Flash to reduce the chance of a Flash exploit taking over a computer (Flash is notoriously problematic from the security perspective). I’ve seen very few real-world exploits that work on Chrome, and even fewer that break through Chrome’s sandbox, when Flash is the target. That’s why I uninstalled Flash from my Mac and view Flash-using sites exclusively with Chrome.

Sandboxing isn’t a panacea. Some entitlements may allow an attacker to do bad things outside the sandbox. Also, sandboxes themselves are software and may be cracked. But, at a minimum, the sandbox adds yet another layer an attacker has to get past before getting a foothold on your Mac, even if the application inside is vulnerable and exploited.

To put it bluntly, based on the nature of attacks today, sandboxing is likely the future on every computing platform.

What does sandboxing have to do with the Mac App Store? — As of 1 June 2012, all new apps and major updates in the Mac App Store must be sandboxed.

Does this mean all Mac App Store apps are now sandboxed? — No. All new apps are sandboxed, but existing apps aren’t necessarily. Apple says they will allow bug fixes to non-sandboxed apps, but not other upgrades. I also get the sense this is a fuzzy line, and some exceptions may be made (at least in the short term).

How will this affect apps? — Some apps, if they wish to use sandboxing, will lose functionality that isn’t provided by existing entitlements. To get a sense of what entitlements are available to developers, check out Apple’s “Enabling App Sandbox” documentation. Apple also offers a set of temporary

entitlements that developers may use only with permission, and that might go away in the future. Accessing the Movies folder is a regular entitlement, while accessing Apple Events (to enable AppleScript-based communication between apps) is a temporary entitlement.

The lack of certain entitlements and developer uncertainty about relying on a temporary entitlement have already affected some apps in the Mac App Store, with some developers eliminating functionality that’s impossible given current entitlement limits and others offering more-capable versions for sale outside the Mac App Store. For instance, Smile’s popular typing expansion utility TextExpander 4 isn’t for sale in the Mac App Store for this reason, while version 3.4.2 remains available there.

On the one hand, users suffer from the loss of functionality and from the confusion of multiple versions of apps, and either approach costs developers time and money. On the other hand, the sandboxing requirement enhances the security of all new and updated apps in the Mac App Store.

Why is Apple mandating sandboxing in the Mac App Store? — Apple has learned a valuable lesson from iOS. There is currently no malware on iOS and we’ve never seen a widespread attack. Contrast this to Google Play and especially the non-Google-supported Android stores, which are riddled with Android app malware. Apple’s App Store requires sandboxing and reviews all apps; Google Play (and the alternative markets) place no such requirements on developers. Apple’s strict control over the App Store provides the safest user experience out there, and while you may not think about it

consciously, the fact is that you don’t have to worry about malware in the App Store doing bad things to your iPhone or iPad.

We see Android cybercriminals using the same techniques they’ve successfully relied upon to exploit Windows users, such as hiding Trojan horses in versions of popular applications, pretending to be security apps, and drive-by downloads.

Even if someone manages to sneak a malicious app into the App Store (as some researchers have done with proofs of concept), or an app is later compromised and used in attacks, Apple could remove it and stop all new infections. (Apple doesn’t uninstall apps from iOS devices, although they could do so with a software update in a really bad situation).

Apple wants to provide this same experience to users on Macs and give us a safe place to buy and install applications. They may not market that as a benefit of the Mac App Store explicitly, but they want security to effectively disappear as a concern for users.

Can bad guys break out of the sandbox? — Probably. Then Apple will harden it again. Then the bad guys will break it again. And so on. No technology is perfect, but sandboxing most definitely raises the costs of attacks. In fact, it so significantly raises the cost of attack that it wipes out entire classes of potential bad guys who lack the technical skills or budget to target and crack the sandbox.

Is there a downside to mandating sandboxing? — Absolutely. Not every application can meet the sandboxing requirements. Macs are general-purpose computers, and by definition, that means that developers can come up with innovative applications that can do things — and need to do things — that Apple has not anticipated and for which there are no entitlements.

Some apps will never be able to be sold in the Mac App Store. This is a problem since, as more users go to the Mac App Store for their apps, it may become economically difficult for those developers to reach a large enough audience.

We don’t know how this will play out in the long term. My hope is that as the overall Mac market share increases it will create more opportunities for both Mac App Store and independently sold applications, offsetting the inability to sell non-sandboxed apps in the Mac App Store. This is clearly an optimistic view, and it’s also entirely possible that the market for smaller developers whose apps can’t be sandboxed and sold in the Mac App Store could shrink to the point of driving them out of business.

Apple also faces criticism, especially from developers, related to other Mac App Store problems (such as unpredictable and poorly supported rejections, the lack of demos, the inability to communicate with customers and respond to user reviews, and more). Mandating sandboxing without addressing these other complaints has increased developer concern and uncertainty, and connected Mac App Store policies and sandboxing in a way that I fear could hurt the perception of this valuable security technique.

Why not make sandboxing optional? — In my experience, optional security is non-existent security. Microsoft has offered sandboxing capabilities for years and practically no developers use them. Microsoft even struggles to get developers to adopt anti-exploitation technologies like ASLR or EMET, despite the fact that there is basically no cost in doing so because the technologies are built into development tools. Heck, it took Microsoft years to convince Apple to enable ASLR for its Windows applications.

Apple wants the Mac App Store to be as safe as possible. Maybe it’s for marketing, maybe it’s for altruism, but the motivation doesn’t matter if the results improve our safety. Based on past history, if Apple doesn’t mandate sandboxing, nearly no developers will likely use it. I hate to word it that way, but I’ve been in the security game for a long time and all my experience, and that of other security professionals, says that, without a stick, only a few horses will eat the carrot.

Does Apple sandbox their own apps? — Not those sold in the Mac App Store. And, to be honest, it would really help their case with developers if Apple would follow their own rules. It would also help Apple better understand developer concerns and improve entitlements if their own teams had to work within the same restrictions. Perhaps they are moving in this direction internally, but the current versions of Apple’s major applications in the Mac App Store (including Aperture, Final Cut Pro, iLife, and iWork) are not sandboxed.

Aside from the poor example this sets, you have to assume that the bad guys are also working to target Apple’s applications — after all, iTunes is nearly ubiquitous on Macs, and if it’s not sandboxed, that makes it all the more attractive as a conduit for malware. iPhoto is probably next on the target list, with GarageBand, Pages, Keynote, Numbers, and the professional apps coming in behind.

Will Apple grant exemptions to any apps or developers? — Possibly, though if this has happened so far, no one is talking. I get the impression Apple’s policy-makers are still feeling their way around, at least internally. (Developers report that any queries about exemptions that aren’t already covered by entitlements are met with resounding silence from Apple.) We’ll need to see if they grant exemptions to sandboxing for any major or innovative developers, but right now the rule is hard and fast. All I can say is that, in my discussions with Apple, I sense that the sandboxing requirement and entitlement list isn’t as final as, say, killing off floppy drives.

Where does Gatekeeper fit in? — Gatekeeper is a new feature in Mountain Lion that enables you to restrict what kind of downloaded applications will run on your Mac. While Apple has designed the Mac App Store and the sandboxing requirement to give users a safe place to buy apps, Gatekeeper is designed to strike at the economic heart of cybercrime.

By default — and most people won’t change this setting — Gatekeeper will allow only two types of downloaded apps to launch on a Mac: those from the Mac App Store, and apps that are digitally signed with an Apple-issued Developer ID.

One of the most common ways to get malicious software onto someone’s Mac is to trick them into downloading and installing it. Criminals use sophisticated techniques that often fool knowledgeable users and even security pros, not just less-experienced users. By preventing downloaded software from launching unless it comes from the Mac App Store or a known developer, Gatekeeper closes the door to this approach to infection.

Bad guys will undoubtedly try to bypass Gatekeeper by, for example, stealing a legitimate developer’s Developer ID, but once again, the addition of Gatekeeper makes it much harder to produce malware that could spread widely, and thus reduces possible profit.

How does Gatekeeper work? — I covered Gatekeeper’s features in depth in “Gatekeeper Slams the Door on Mac Malware Epidemics” (16 February 2012), but here is a quick summary:

- Gatekeeper enables you to restrict which downloaded applications can launch on your Mac. There are three possibilities: Mac App Store only, Mac App Store plus Developer ID-signed applications, and no restrictions. The default is to allow Mac App Store apps and Developer ID-signed apps.

- Gatekeeper checks only applications downloaded using programs (like Web browsers) on a list Apple maintains. Thus not every downloaded file is quarantined, nor are files transferred using cloud-storage services like Dropbox, USB flash drives, CD/DVDs, or other media.

-

You can override Gatekeeper and run any arbitrary application by Control-clicking it and choosing Open, but this command is intentionally concealed to make the process non-intuitive and, at minimum, to make the user realize something strange is going on. Apple has purposely made it more difficult than merely clicking an Open Anyway button in a dialog, since we users have a tendency to click whatever appears.

-

Gatekeeper checks downloaded applications only the first time they run. And, of course, since it checks only downloaded apps, it won’t check any already installed applications when you upgrade to Mountain Lion.

There’s a lot more to Gatekeeper, but the main thing to know is that once you upgrade to Mountain Lion you won’t be able to run newly downloaded applications that aren’t from the Mac App Store or signed with a Developer ID unless you jump through a few extra hoops.

Are most developers using Developer IDs? — Not yet, but adoption is growing quickly, according to my sources at Apple. Major publishers like Adobe are issuing updates for their applications, and I know many of the smaller apps I use regularly have been updated with a Developer ID. If you’ve been following the updates we publish in the TidBITS Watchlist, you’ll notice that we’ve been mentioning when developers are signing their apps in order to support Gatekeeper.

How does restricting where my apps come from improve security? — Most users never change the defaults on their Macs. As we’ve already discussed, limiting which applications can launch to those that come from the Mac App Store means you’re getting only apps that are vetted by Apple. Many of those are also sandboxed; eventually all will be.

But, as we’ve also discussed, not all programs can meet the Mac App Store’s sandboxing requirements. Had Gatekeeper drawn a distinction between only those apps in the Mac App Store and those not in it, a large percentage of users would have opted for no restrictions, since it would have been too frustrating to deal with applications downloaded from other sources. The beauty of allowing Developer ID-signed apps to run by default is that we can still install most legitimate apps with no fuss, but Apple maintains control at a developer level rather than an application level.

Members of the Mac Developer Program (which costs $99 per year) can use their free Developer IDs to sign whatever they want, and Apple doesn’t review signed apps. However, should a signed app be discovered to be malicious, Apple can place that developer’s certificate on a blacklist and Gatekeeper will prevent additional users from installing any apps from that developer.

This technique could dramatically reduce the spread of malware. Even if a criminal manages to get, or steal, a Developer ID, the moment they are discovered and Apple blacklists that ID, the malware is prevented from spreading on any more Gatekeeper-enabled Macs.

Gatekeeper isn’t a perfect security control, and it isn’t meant to be. By focusing on widespread attacks Apple is reducing the economic viability of Mac malware spread by tricking users into installing bad things. Combine this with the increased hardening to reduce exploits of the Mac itself, and it becomes much more expensive to attack Macs.

(And yes, developers should seriously protect their Developer IDs, since if a Developer ID is stolen and used in malware, Apple’s blacklist would also apply to all legitimate software signed with that Developer ID, causing an immediate drop in sales and a serious reputation hit. Apple has a poor track record in working with developers to address problems, so I can imagine quite some time passing before such a situation could be resolved.)

What worries users and developers about these security technologies? — In a word, iOS, which shows both the benefits and the risks. We have never before seen these sorts of restrictions on our general-purpose Macs, but we have seen them in action in iOS, where there are notable limitations on what can be done (the lack of a centralized file system is a notable example) and where Apple has regularly misused its role as gatekeeper.

The limitations imposed by sandboxing have developers worried that they either won’t be able to innovate freely and exist within the Mac App Store’s sandboxing requirements, or that they won’t be able to reach a large enough market outside the Mac App Store to justify development costs. Developers are also worried that, as we’ve seen in the iOS App Store, the rules will change or that Apple simply won’t abide by them. There are multiple cases of Apple behaving capriciously, rejecting otherwise legitimate apps without reason. For developers to invest the significant time and money into development, the marketplace has to be run in a fair and aboveboard manner. Without consistent rules, markets can’t survive.

I’ve also talked with lots of developers and power users alike who worry that Apple wants complete control over what we run on our Macs. They worry that Apple will, in the future, mandate that everything go through the Mac App Store and be sandboxed, or that so much of the market will rely on the Mac App Store that there will be no way for software to survive outside of it. The concern is that the end result may be more safety for the average user, but at the cost of freedom — and advanced capabilities — for professional users.

I may love my iPad, but I equally love all the wonderful tools and tweaks of my Macs, many of which wouldn’t be possible in a completely sandboxed world.

I can’t predict the future, but my personal feeling is that the current team at Apple recognizes the differences between a general purpose computer and an iOS device. The fact that they created the Developer ID instead of merely using Gatekeeper to force the use of the Mac App Store is a sign that they want to balance freedom and safety. Apple has also expanded sandbox entitlements, although calling them “temporary” makes any company relying on them wonder when the rug will be pulled out.

If there is one thing I hope Apple learns if they read this article, it’s that users and developers may appreciate the safety of this strategy, but they very legitimately fear where we may be headed if Apple exercises too much control. Sandboxing and the Mac App Store are so interconnected that if sandboxing is perceived as a tool to control the overall user experience versus protecting users, it will negatively affect perceptions. Apple is big enough and powerful enough to do whatever it wants, but going to the logical extreme would be a harsh blow for those users most invested in the Macintosh way, to reference Guy Kawasaki’s first book (now available as a free

download).

While I don’t personally think that Apple wants the Mac to become as locked-down as an iOS device, we all need to admit it is a legitimate concern, considering how much of iOS has made its way into Lion and how much more is coming in Mountain Lion.

As someone who lives in the security world, I think Apple is moving in the right direction, albeit with room for improvement. These security technologies and techniques have proven effective in targeting the big picture problems, and I suspect Microsoft will need to adopt similar ecosystem approaches as they move into Windows 8 (which is already inherently quite secure). But I hope Apple recognizes why so many experienced users and developers are concerned, and some clearer communication might assuage at least a few of those fears.

TidBITS Watchlist: Notable Software Updates for 26 June 2012

TextExpander 4.0 — Smile has released TextExpander 4.0, a major update to its typing shortcut utility with several new features for automating longer texts such as form letters. Aside from new features, however, the new release is also notable for the fact that Smile won’t be releasing this latest version of TextExpander via the Mac App Store due to Apple’s sandboxing requirements (which, in this case, would prevent TextExpander from working inside other apps, which is its raison d’etre). TextExpander 4.0 is available only from the Smile Web site for $34.95 new and $15 for an upgrade from a previous version

(though you can get a free upgrade if you purchased TextExpander after 15 January 2012). Additionally, TextExpander 4.0 now requires Mac OS X 10.7 Lion and later (version 3.4.2 remains available in the Mac App Store for 10.6 Snow Leopard users).

As for new features, the release adds new “fill-in-the-blank” snippet options that enable you to create a template that can be personalized with names and dates as well as custom links or HTML tags with variable attributes. It also offers fill-in capabilities for multi-line text fields, pop-up menus for multiple choices, and optional text blocks that can be triggered as needed. For those new to TextExpander, the app now includes a Snippet Creation Assistant that provides step-by-step guidance on creating new snippets, and the interface has been tweaked to create fill-in snippets via a pop-up menu. Other enhancements include default values for text fields and pop-up menus, snippet expansion when filling out a text field, and the

addition of French and German AutoCorrect snippet groups. ($34.95 new with a 20-percent discount for TidBITS members, $15 upgrade (free for purchases after 15 January 2012), 8.5 MB, release notes)

Read/post comments about TextExpander 4.0.

Skype 5.8.0.865 — Updating to version 5.8.0.865, Skype for Mac adds several user interface improvements as well as support for the upcoming release of OS X 10.8 Mountain Lion. The update includes an improved Contacts Monitor (which can be more compactly resized when using other applications), automatic reorientation of mobile video calls when the mobile device switches between landscape and portrait views, the addition of a keyboard shortcut for controlling volume, and an SMS button in the conversation input field. Skype Premium subscribers also get improved screen sharing with the addition

of simultaneous video call and screen sharing views. For a complete overview of the improvements, see this Skype Garage blog post for the release notes. (Free, 23.3 MB)

Read/post comments about Skype 5.8.0.865.

Bento 4.1.1 — FileMaker has released version 4.1.1 of its simplified Mac database software Bento, which offers no new features save for the addition of a Simplified Chinese localized version. Rather, the focus of this release is adding compatibility with its recently updated iPad app. The Bento 4 for iPad app adds several new ways of accessing your data, including a Form view, a spreadsheet-like Table view, a Split view that combines the Table and Form views, and a Full Screen view with a Libraries sidebar. It also

includes 40 new Retina display-ready themes and single-tap access to the Bento Template Exchange for access to a wealth of free, ready-to-use templates.

Bento 4.1.1 for Mac is a free update for current owners (whether purchased from FileMaker or the Mac App Store), and it has been discounted to $29.99 (from $49.99) through 31 July 2012 for new users. Similarly, Bento 4 for iPad is available for a discounted $4.99 through 31 July 2012 (regularly $9.99). However, there is no free or discounted upgrade path — or future updates — for owners of the previous edition of Bento for iPad (version 1.15), even if you purchased the older iPad version just days ago. Megan Lavey-Heaton at TUAW has some suggestions on who

to contact if you recently purchased the old version 1.15 and are looking for a refund. (Mac version $49.99 new with limited-time $29.99 discount, free update, 98.6 MB)

Read/post comments about Bento 4.1.1.

ExtraBITS for 26 June 2012

Only one quick hit this week, but you’ll find plenty to read, since it’s a collection of interesting responses to an NPR intern revealing that she has purchased almost none of the music in her 11,000-song collection.

NPR Intern Rekindles Debate about Paying for Music — An NPR intern on the “All Songs Considered” program posted recently about how she has 11,000 songs in iTunes, but has purchased only about 15 CDs in her life. Her post prompted a firestorm of responses — pro and con, interestingly — and NPR’s Robin Hilton links to a number of them in this blog post. Most notable is the “Letter to Emily White” from David Lowery, a songwriter and lecturer at the University of Georgia’s music business program, but it’s worth reading a number of the

articles Hilton references.