TidBITS#1305/25-Jan-2016

Apple last week released both OS X 10.11.3 El Capitan and iOS 9.2 with minimal (and mostly unspecified) bug fixes — we explain what’s known and why it may be worth waiting a week before updating. Apple also updated the fourth-generation Apple TV to tvOS 9.1.1, bringing back the Podcasts app, and our Apple TV expert, Josh Centers, offers a guided tour of the new app. Security Editor Rich Mogull joins us to explain why Apple — in the form of CEO Tim Cook — is constantly defending encryption despite government pressure. Finally, Julio Ojeda-Zapata reviews Apple’s CarPlay system for integrating iPhone capabilities into car touchscreens. Notable software releases this week include iMovie 10.1.1, Parallels Desktop 11.1.2, Nisus Writer Pro 2.1.3, ClamXav 2.8.9, and Security Update 2016-001 (Mavericks and Yosemite).

OS X 10.11.3 and iOS 9.2.1 Bring Bug Fixes

Apple has released OS X El Capitan 10.11.3 and iOS 9.2.1. The release notes on both updates border on the nonexistent. For 10.11.3 in the App Store app, Apple says:

This update contains bug fixes and security updates.

The support document referenced for additional details gives only two specific changes, the second of which is likely of interest mostly to enterprise users.

Fixes an issue that may prevent some Mac computers from waking from sleep when connected to certain 4K displays.

Third-party .pkg file receipts stored in /var/db/receipts are now retained when upgrading from OS X Yosemite.

For iOS 9.2.1, Apple says:

This update contains security updates and bug fixes including a fix for an issue that could prevent the completion of app installation when using an MDM server.

Again, that’s relevant chiefly for enterprise users.

The updates also address a handful of security vulnerabilities: nine in 10.11.3 and nine in iOS 9.2.1. As a reminder of how much code is shared between OS X and iOS, five of the vulnerabilities were the same on both operating systems.

You can install the OS X 10.11.3 update (661 MB on an iMac with 5K Retina display) via Software Update or from Apple’s Support Downloads page (662 MB for the delta updater from 10.11.2 or 1.47 GB for the combo updater from any version of 10.11). Install the iOS 9.2.1 update (37.7 MB on an iPhone 6) via Settings > General > Software Update, or through iTunes.

Unless the enterprise-related fixes are essential for your organization, we recommend holding off on these updates for a week or so. When Adam updated to 10.11.3, his iMac hung at a black screen with a Restarting progress bar two-thirds filled. It came back up properly — fully updated — after he powered it down, but on the off chance that his experience is indicative of a more general problem, delay the update for a bit and watch for reports from other users. When you do decide to update, make sure to make a backup first!

Apple Brings Back Podcasts in tvOS 9.1.1

Hot on the heels of updates for OS X and iOS, Apple has released tvOS 9.1.1 for the fourth-generation Apple TV. You can obtain the update by going to Settings > System > Software Updates > Update Software.

There are no release notes, but there is one obvious new feature: the return of the Podcasts app, which appears on your Home screen after updating. If you use Apple’s Podcasts app for iOS or listen to podcasts with iTunes, the Apple TV version can sync your subscriptions and episodes with those clients. Unsurprisingly, Podcasts for tvOS also supports video podcasts and provides a great experience for watching them.

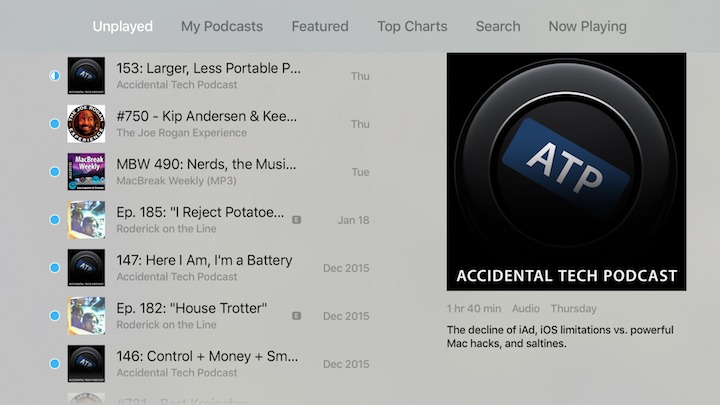

The Podcasts app is split into six screens:

- Unplayed: If you subscribe to podcasts, the episodes you haven’t yet finished will appear here. Select an episode to play it.

-

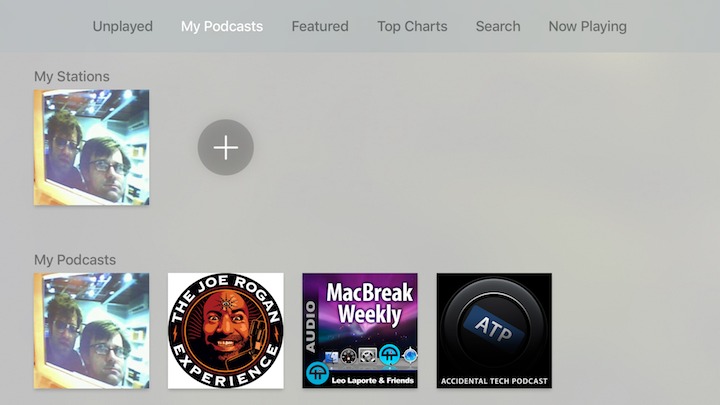

My Podcasts: Your subscribed podcasts, if you have any, appear here. You can also create “stations,” which are like playlists for podcasts, that appear alongside subscribed podcasts in this screen.

-

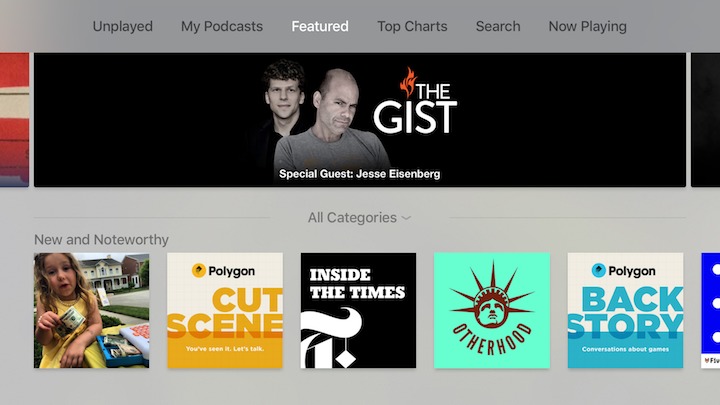

Featured: This screen lists podcasts selected by Apple’s editors. You can open a podcast to watch or listen to individual episodes or to subscribe to see new episodes as they are published.

-

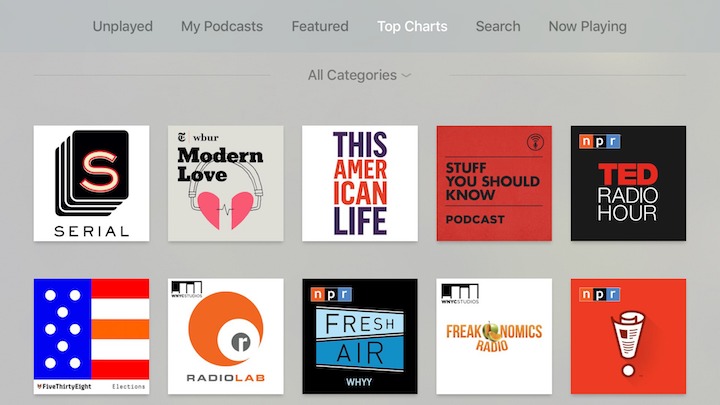

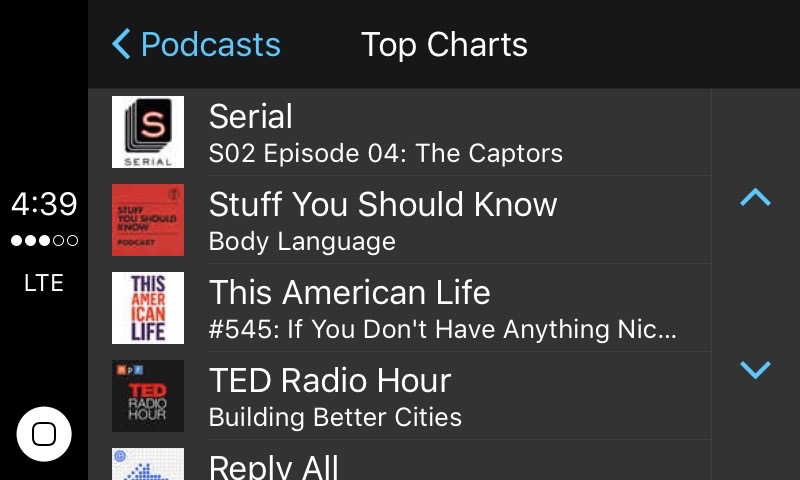

Top Charts: The Top Charts screen lists the most popular podcasts, and you can choose to view them by category. As with the podcasts listed in the Featured screen, you can play individual episodes or subscribe.

-

Search: You can search for podcasts here. The Search screen also displays a list of popular podcasts in case the contents of the two previous screens weren’t sufficient.

-

Now Playing: In this screen, you can see and control the currently playing episode and see what’s next in the queue. When you first enter the screen, it displays just the currently playing episode’s show art and title. Press the Siri Remote’s touchpad to see the episode timeline, which you can scrub through by swiping left or right on the touchpad. If you swipe up and click the … button, you can subscribe to the podcast and choose the output speaker. If you’re subscribed to the podcast, the … button lets you mark the episode as played, view the full episode description, and choose the output speaker.

The Podcasts app is a nice addition, but we’re looking forward to Bluetooth keyboard support and Home screen folders, both of which are slated for the upcoming tvOS 9.2 release. In the meantime, I’ll be on the lookout for more changes in tvOS 9.1.1 as I continue working on the next edition of “Take Control of Apple TV.”

Why Apple Defends Encryption

The Intercept recently reported that Apple CEO Tim Cook, in a private meeting with White House officials and other technology leaders, criticized the federal government’s stance on encryption and technology back doors (see “Tim Cook Confronts the White House Over Encryption,” 14 January 2016). As it was a private meeting, we don’t know exactly what happened, and The Intercept is admittedly biased on this issue, but such statements would certainly align with Cook’s previous public positions. This is just the latest of Apple’s spats with the U.S. government over encryption — I first wrote about

them in “Apple and Google Spark Civil Rights Debate” (10 October 2014).

Cook’s dustup with the White House prompted Daring Fireball’s John Gruber to ask:

This came up during last night’s Republican primary debate — not about tech companies refusing to allow backdoors in encryption systems, but about Apple specifically. Tim Cook is right, and encryption and privacy experts are all on his side, but where are the other leaders of major U.S. companies? Where is Larry Page? Satya Nadella? Mark Zuckerberg? Jack Dorsey? I hear crickets chirping.

These aren’t nebulous questions from privacy activists or Apple enthusiasts. We are in the midst of fundamentally redefining the relationship between governments and citizens in the face of technological upheavals in human communications. Other technology leaders are relatively quiet on the issue because they lack the ground to stand on. Not due to personal preferences or business compromises, but because of their business models, and lack of demand from us, their customers.

(Apologies to our international readers, but this article is U.S.-centric since the issues vary depending on where you live. That said, a number of other governments, like those of the UK and France, are dealing with exactly the same situation.)

Why Governments Want to Read Your Mind — When we talk about encryption and privacy from government surveillance, we’re really discussing three separate, but related, issues:

- Our right to use technology that keeps our data and activity private from law enforcement agencies.

- The legal right and capability of our intelligence agencies to monitor our online activities and communications.

-

Intelligence and law enforcement agencies either mandating or creating (legal or not) “back door” access mechanisms in commercial products and services to monitor activity.

Encryption plays a massive role in each of these issues, but it’s only part of the story.

Civilian law enforcement agencies that serve “the law,” not government leaders, are actually a relatively recent development in the history of the world. The concept is “policing by consent,” which comes from the Peelian Principles of policing. Law enforcement is separate from the military and from intelligence agencies. We give police extraordinary, but not unlimited, powers to allow them to enforce the law and protect citizens. In the United States, multiple agencies at multiple levels (local, state, and federal) interoperate with the judiciary to create a series of checks and balances on power.

In America, law enforcement agencies at all levels have a long history of accessing personal information as part of their investigations. Police are accustomed to obtaining evidence from nearly any source, with the appropriate legal authority, via a process called “lawful access.” The police can crack a safe, tap your phone, read your mail, access your financial records, and more, as long as they have the right authority. That may require asking a judge for a warrant (to read your physical mail); in other situations, the information is available using techniques with lower evidentiary standards (tracking your car with GPS, since public movements are… public). Regardless, all these situations are within the framework of the law.

There are even laws that mandate telecommunications companies create back doors for lawful access.

The problem for the police is that new technologies block their ability to access information they need (or at least think they need) to do their job. Mobile phones, for example, have become one of the best information sources in law enforcement history since they consolidate a suspect’s communications and personal data into one tidy package. Sure, police can get texts, call, and location histories through a phone carrier, but it’s much faster and easier to pull it from the phone, which also likely contains Facebook posts, encrypted iMessages, email conversations, and a lot more.

This is the first time in history we have civilian communications and information storage devices that law enforcement can’t access, even with a warrant. That’s a slight exaggeration, since you can be compelled to unlock your phone (your passcode can’t be tortured out of you, but a judge can toss you in jail until you give it up). And as I said, most — but not all — of the information on a phone is typically available in other places, but getting it elsewhere is far more time consuming than looking on the phone.

Law enforcement officers see strong encryption as a tool that impedes their ability to do their job, using tools they have never previously been denied.

Intelligence agencies are different. They aren’t supposed to monitor U.S. citizens (except for a few very narrow exceptions). Even the bulk data collection that’s come to light in recent years has limits and is predominantly focused on monitoring foreign communications, including those into and out of the United States. Intelligence agencies don’t enforce the law, they spy, on other nations and potential threats. But in recent decades they’ve faced a massive legal and logistical problem — a large portion of the technology they need to use relies on products and services that originate in the United States.

If intelligence agencies need to tap bad guy email communications in Europe, they often need to crack into the likes of Google, Microsoft, and other services. Or at least tap them internationally, since they are explicitly not allowed to tap domestically. But as those who understand how the Internet works know, the lines between domestic and international aren’t always clear.

And “tap” is a misnomer. Technology companies use encryption to protect information and transactions from attackers. That same encryption is powerful enough to impede intelligence agencies, or at least increase the costs for them to crack it. So they may know about some software vulnerabilities that let them break into systems. Or maybe they look at putting in a secret “back door.” Except there are no secrets, and every back door is a security vulnerability just waiting to be exploited. Plus, deliberately introducing vulnerabilities or back doors in domestic systems is not only likely a violation of law, but also of the

policies and operating procedures of the intelligence agencies themselves.

Both law enforcement and intelligence agencies face the same fundamental problem. Any tool that enables lawful access also enables unlawful access. There are no Golden Keys, only skeleton keys.

Thus:

- While we have a legal right not to incriminate ourselves to law enforcement, law enforcement has historically had access to anything we have ever recorded or communicated. Until now.

-

Intelligence agencies are tasked with spying on foreigners in order to protect us, but the lines between “foreign” and “domestic” are blurrier than ever.

-

Back door access for law enforcement (and, sometimes, intelligence agencies) has previously been legally mandated. But every back door is not only a vulnerability, but also potentially a tool for abuse, from criminals or hostile governments.

To top it all off, existing laws in many of these areas are often unclear or obsolete, at a time when the ability to access our devices and services is effectively akin to reading our minds. These fights over our online rights are fundamentally redefining the relationship between citizens and governments.

Why Apple Takes a Stance Where Others Don’t — Apple is far from the first company to find itself in government crosshairs. BlackBerry, for example, was forced to decrypt communications for the Indian government in 2010 or shut down operations in the country. Those same tools have since expanded and are used in other countries to monitor BlackBerry devices.

Let’s go back to Gruber’s list: Google, Microsoft, Facebook, and Twitter. I’ll add Amazon and Samsung. In each case, these companies’ business models don’t give them the same freedom to speak out as Apple enjoys.

Google is fundamentally an advertising company that collects data on its users. That information can’t be encrypted so only the user can see it, since that would prevent Google from accessing it and using it for targeted advertising. Even removing the ad issue, some of Google’s services fundamentally won’t work without Google having access to the underlying data. Google is taking a stronger stance with Android encryption, at least on the technology side (slowly, because Google doesn’t control most Android hardware). But Google isn’t vocal about this since all its data is accessible with a warrant. It isn’t in the company’s interest to call attention to this fact. However, I do know that Google does whatever it can to

prevent spying and other monitoring, such as encrypting all communications between its data centers.

Microsoft is fundamentally a software company. The firm already offers strong encryption for PCs (BitLocker), but it isn’t consumer friendly and Microsoft owns only a tiny fraction of the mobile market. Its biggest customers, corporations and governments, are long used to monitoring Microsoft platforms for legitimate enterprise security reasons. Of all the companies here, Microsoft is in the best position to back up Apple, but Microsoft has such a long history of working with, and selling to, government that the company shies away from public conflict on this issue. Outside of the public eye, Microsoft is currently being held in contempt of court as the

company battles the Department of Justice to protect user data stored overseas in a case that could define the future of cloud computing.

Facebook and Twitter? All data in social networks is accessible via lawful access (heck, most of it is effectively public anyway). Like Google, these companies are essentially ad platforms that need access to our data. While Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg and Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey may support strong encryption as individuals, there isn’t anything their companies can do about it on a practical level. Amazon? It doesn’t sell the hardware that matters, and as primarily a retailer, it isn’t in a position to do or say anything that will make a difference. (The exception is in Amazon Web Services, which makes extensive use of encryption, including government-proof options.) Samsung? Samsung is a foreign company that the U.S. government

would be unlikely to take seriously.

Massive tech companies like Cisco, IBM, Oracle, and even HP simply aren’t in the right part of the market to advocate on behalf of consumers, even if they wanted to. And like Microsoft, they have a lot of government contracts.

All these companies place a high priority on the security of their products and services, but, for the most part, they can’t build things that allow us to control our information and keep it private.

And again, to be perfectly clear, any time you enable monitoring, you reduce privacy and security. Every back door is a security vulnerability. This is the technology equivalent to a law of physics, not some technical problem we haven’t solved yet.

Apple is nearly unique among technology firms in that it’s high profile, has revenue lines that don’t rely on compromising privacy, and sells products that are squarely in the crosshairs of the encryption debate. Because of this, everything Apple says about encryption comes from a highly defensible position, especially now that the company is dropping its iAd App Network.

Not everything Apple makes is immune from monitoring. The company must still comply with government requests for data that can’t be encrypted and lives on Apple servers, particularly for services like iCloud Mail, iCloud Drive, and iCloud Photo Library, all of which are subject to lawful access. Wherever possible, Apple uses strong encryption that even it can’t access, as long as the technologies and user experience align.

And Apple, like most of these companies, only provides data when all the right legal boxes are checked. To do otherwise would expose the company to lawsuits.

There’s probably even more to Apple’s stance on encryption than the company’s business model and desire to promote a competitive advantage. My opinion, without having ever talked with Tim Cook, is that this is at least partially social activism on his part. I suspect that this is an issue he cares about personally, and he has the soapbox of one of the most powerful and popular companies in the world under his feet.

We can hope that Larry Page, Satya Nadella, Mark Zuckerberg, Jack Dorsey, Jeff Bezos, and other tech CEOs will someday also speak out on these issues. But their personal feelings aside, they aren’t in the same position as Tim Cook and Apple to take a stand.

Now is the time when we get to decide if we have a right to privacy and security, and the limits of our government for the digital age. It won’t happen because of public statements by tech leaders. No, it’s up to us to make our opinions about online privacy and security known to our elected representatives, in order to determine the limits of policing (and protecting) by consent.

In fact, you have an opportunity to weigh in right now. A bill has been introduced in New York State that would ban the sale of smartphones within the state unless they can be decrypted and unlocked by the manufacturer. It’s astonishingly misguided, and for those who want to express their disbelief that elected representatives could be so ignorant of technology (and geography), you can set up an account with the New York State Senate, vote against it, and even leave comments. The state of California has introduced an equally asinine law, though there

isn’t any sort of feedback mechanism other than contacting your state representative.

Then, just sit back and wait for the next ignorant statement or misguided piece of legislation, because these issues aren’t going to be resolved easily, quickly, or definitively.

CarPlay Offers Limited, Glitchy iPhone/Auto Integration

My iPhone 6s Plus is an indispensable companion in the car. It’s a navigator, a podcast player, a jukebox, a telephone, and more.

Since my humble Mazda 5 lacks a touchscreen like those in fancier cars, my iPhone has filled this role while installed on the dash or windshield via a third-party mount.

I’m satisfied with this, but for those buying a new car this year, Apple has a supposedly better way: CarPlay.

In a collaboration between Apple and an assortment of car makers, iPhone functions are now accessible right on those touchscreens. This occurs when the iPhone is connected to the vehicle via USB, turning the car into a gigantic phone accessory. CarPlay works with models going back to the iPhone 5.

The car’s native touchscreen features don’t go away. Instead, CarPlay becomes one more option — an app, essentially, mixed in among other apps the auto maker provides. (The same is true for Android users in vehicles supporting Google’s Android Auto, a CarPlay competitor.)

In the on-loan Buick Regal luxury sedan and Chevrolet Silverado truck that I used to research this article, drivers have a sophisticated suite of touch controls called, depending on the car make, IntelliLink or MyLink. When an iPhone is connected via USB, a CarPlay button materializes among Chevy’s other options. Think of it as an operating system within an operating system.

Here’s how that looks on the Regal.

And on the Silverado.

Tapping the CarPlay icon fires up familiar options for phone calling, messages, navigation, music, audiobooks, and more. The interface is customized for drivers, much as the Apple TV interface is tailored to couch potatoes. CarPlay icons and menu options are bigger and easier to tap than those on the iPhone.

Most of CarPlay’s capabilities can also be controlled using Siri. You can ask Siri to play music, open apps, find directions, initiate phone calls, dictate text messages, and more.

Apple intentionally limited CarPlay in a lot of ways, in order to omit potentially hazardous features. You can’t play videos via the CarPlay flavors of Apple’s Podcasts and Music apps, for instance.

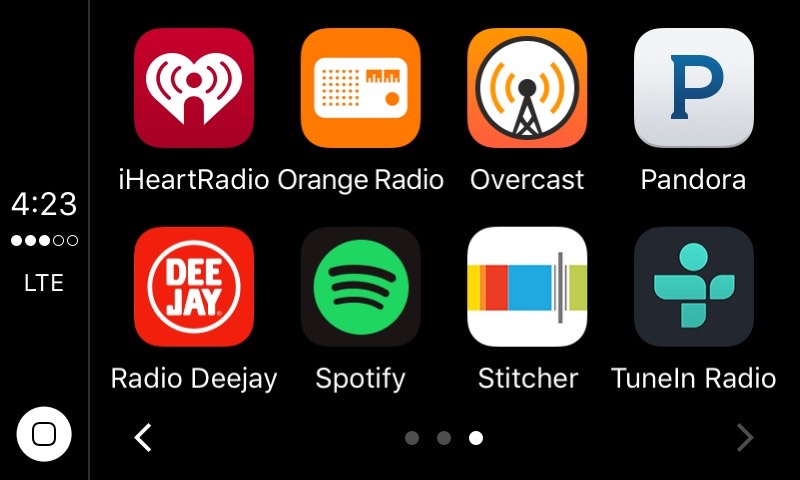

At the same time, CarPlay significantly boosts a car’s infotainment capabilities via CarPlay-savvy apps such as Audible, iHeartRadio, NPR One, Pandora, Spotify, Stitcher, TuneIn Radio, and Marco Arment’s podcast player Overcast. If an app that supports CarPlay is on the iPhone, that app shows up on the console. I found fewer than 20 CarPlay apps, but even that pitiful showing is better than the number of native IntelliLink/MyLink apps Chevrolet offers (Pandora and XM Radio are pretty much it for third-party services).

CarPlay was announced in its current form in March 2014, though the concept had been in the works for a number of years. The technology has been agonizingly slow to show up in vehicles available to the public, but is now finally becoming more prevalent.

Just in recent weeks, Ford, Fiat Chrysler, and Hyundai announced they’d be making CarPlay broadly available in 2016, joining General Motors, Honda, Volkswagen, and others. Chevrolet claims it makes available more 2016 models with CarPlay (and Android Auto) than any other automotive brand.

According to Apple, almost every major car maker has released or will soon release autos with CarPlay.

CarPlay is also available as an aftermarket option via replacement head units from companies like Alpine, Kenwood, and Pioneer.

In my CarPlay testing over two weeks — one with the Silverado, another with the Regal — I found it to be equal parts enjoyable and frustrating. On the plus side, I vastly preferred using an Apple-designed interface over the one provided by the car maker. What iPhone user wouldn’t? At the same time, CarPlay’s simplified nature irked me after having used a full-featured iPhone in my car for years.

The touchscreens in my test cars weren’t up to Apple specs, either, with sub-Retina resolutions and less-responsive surfaces. The Regal display performed better than the one in the Silverado, but both pale in comparison to iOS device screens.

In addition, my CarPlay use was occasionally marred by hanging apps, blank screens, and other glitches.

As I used CarPlay, I kept thinking that my iPhone screen is better in almost every way, save for its smaller size. I’m pretty happy with the third-party mounts I’ve used with my iPhone, but for others, CarPlay’s use of the built-in touchscreen might be a significant usability win in terms of placement and proximity.

CarPlay Tour — The CarPlay interface is simple — mostly in a good way.

It consists mainly of seven Apple-app icons: Phone, Music, Maps, Messages, Now Playing, Podcasts, and Audiobooks (in that order) on a grid two icons tall and four wide. A Home button sits in the lower left. Above that is the time along with cellular and Wi-Fi reception readouts.

As CarPlay-compatible apps are installed on the phone, they show up on the auto’s console. One third-party app filled the last berth on my home screen, and additional apps took up residence on the second and third screens. Annoyingly, third-party apps are sorted alphabetically and cannot be manually rearranged across the various screens.

Moving among screens was intuitive, with left and right swipes, though the subpar responsiveness of the car touchscreens made even such simple swipes annoying at times.

CarPlay versions of Apple and third-party apps have consistent, more-generic interfaces compared to their iPhone versions. Apps also tend to be light on features compared to their full iPhone equivalents. This is good, in the sense of reducing complexity in an environment with far too many distractions, but it also makes the CarPlay experience a bit bland.

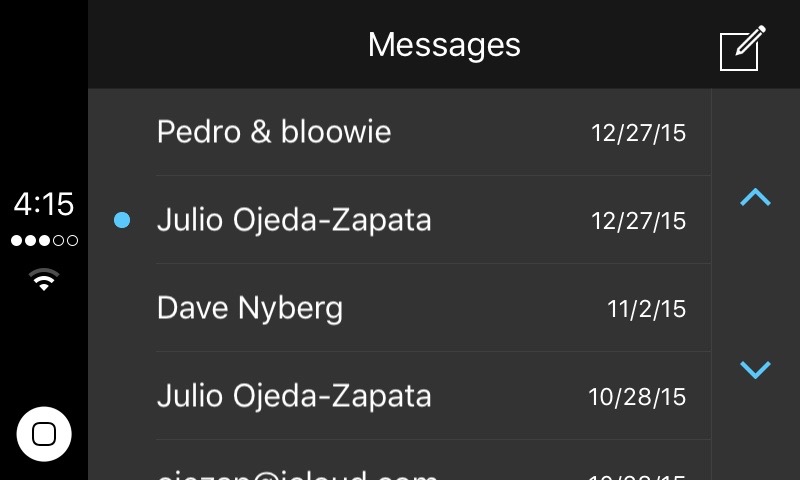

For instance, in Messages, there’s no option to type in new messages on the screen or to see old ones in text form. All that’s displayed is a list of people with whom you have interacted recently. Siri reads you messages from those people and prompts you to dictate your replies. There’s also an onscreen compose button, which fires up Siri, or you can access Siri by pressing and holding a physical Siri button built into the steering wheel.

The Audiobooks app is minimalist, too, showing just a list of the audiobooks you’ve bought. Tap one, or ask for it via Siri, and it starts playing. The app does not narrate text-based iBooks.

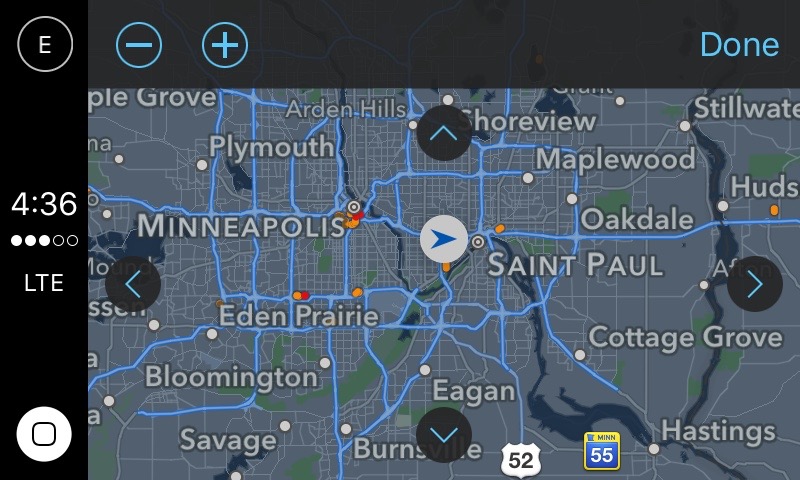

Maps is another exercise in simplicity. Your location is shown on a map, and there are simple zoom and pan controls along with a 3D option. You can’t use pinch-to-zoom as you’d expect.

Maps provides turn-by-turn directions, audibly and on screen, along with traffic conditions and travel times. It also shows a list of recent destinations; tap one to fire up driving directions.

Routing a fresh trip happens via Siri. Again, there’s no typing required.

When routing is in progress and the motorist shifts to another app (Overcast shown below), a Maps shortcut icon appears on the upper left of the display to make getting back easier.

Apple’s mapping looks fantastic on the Regal’s display — much nicer than the built-in navigation features in most cars I’ve seen.

A recently released iOS 9.3 beta adds a Nearby option to CarPlay screens for those wanting tips on nearby restaurants, gasoline stations, coffee shops, hotels, parking lots, supermarkets, and more.

The CarPlay version of the Phone app provides a keypad for initiating voice calls, along with tappable lists of favorites, recents, and voicemails. Drivers can use Siri to initiate calls, return missed calls, and access voicemail.

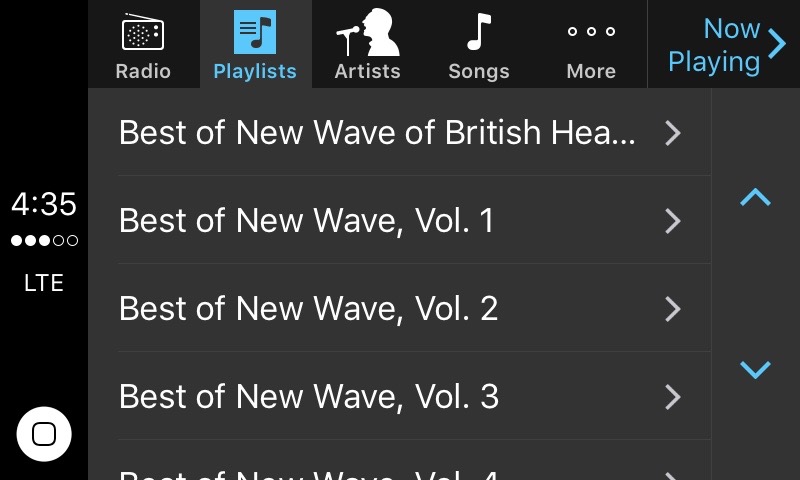

The Music app is somewhat more elaborate, especially now that the Apple Music streaming service is part of the mix. My purchased songs, along with all of my iTunes and Apple Music playlists, were just a tap or two away.

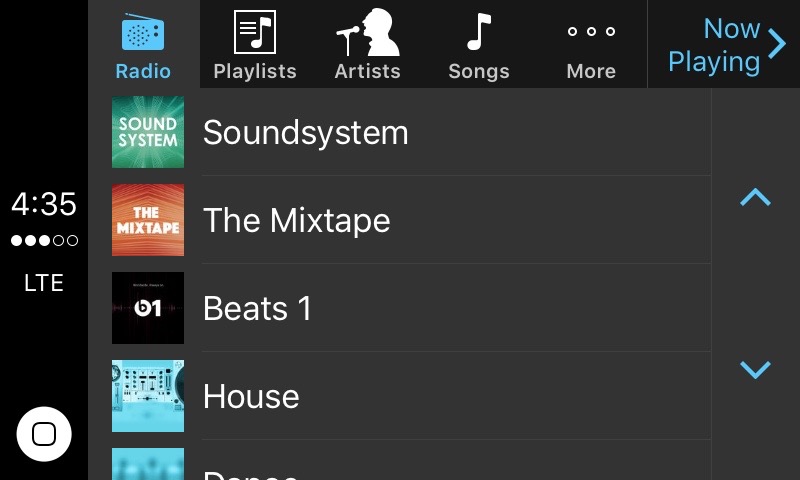

So were all my radio stations — including Apple Music’s signature Beats 1.

But much of Apple Music was inaccessible to me during my testing. To get at For You, New, Connect, and other features, I needed my iPhone. That’s good — the mental concentration required to navigate Apple’s ludicrously complex music interfaces would send most drivers into the ditch. Unfortunately for them, the new iOS 9.3 beta adds New and For You to the CarPlay auto displays.

I could not, of course, watch A-ha’s “Take On Me,” the best music video ever made (yes, I’m a child of the 1980s), and one I had been watching obsessively on my MacBook, iPhone, and iPad. I own the video, but CarPlay wouldn’t permit me to display it on my Regal console for safety reasons. That’s true even if the car is stopped (idling or even parked).

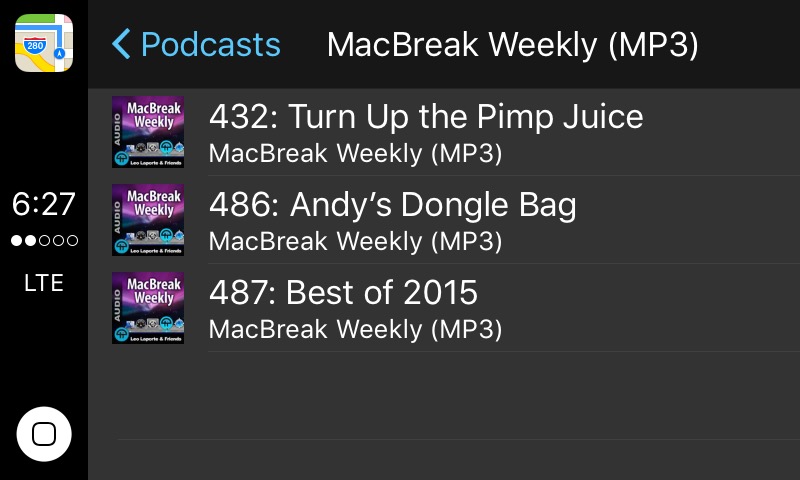

It is much the same with the Podcasts app. While the iPhone version of the app has access to both audio and video podcasts, the CarPlay version is audio-only. No matter; it’s a convenient way to fire up a decent show at random — like Serial or Stuff You Should Know — via the Top Charts section.

All of my podcast or station settings were available, as well.

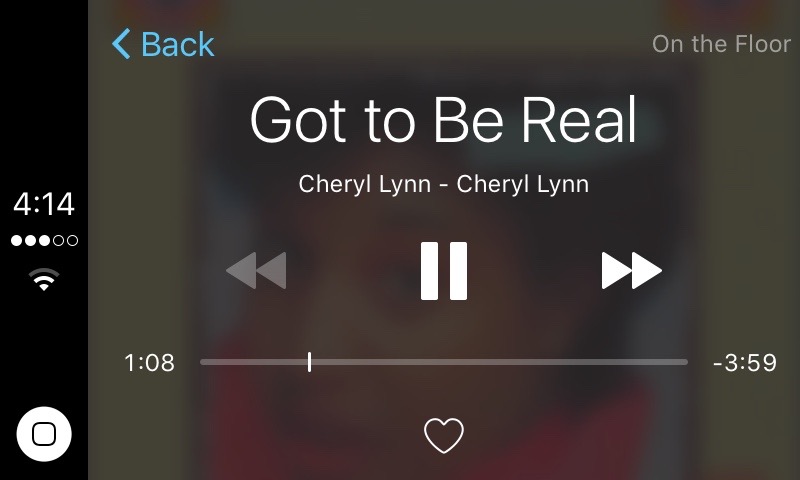

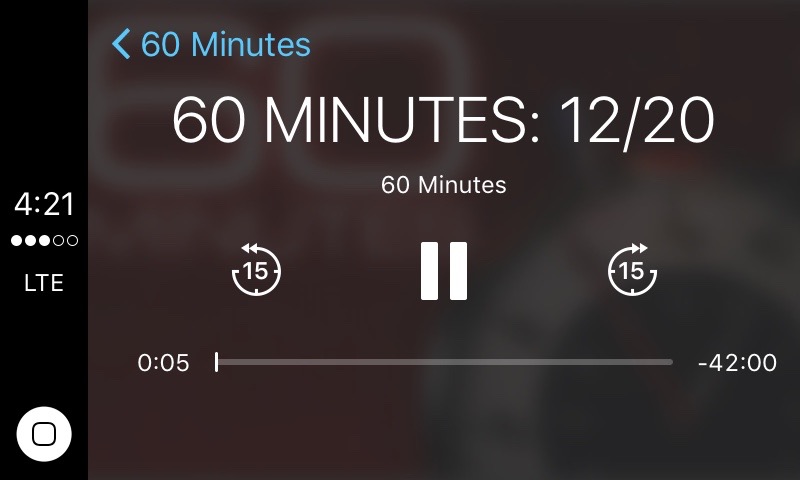

Perhaps the handiest button on the CarPlay interface is also the simplest: Now Playing. It’s self-explanatory — a tap of the button displays your audio selection’s player, with its rewind, fast-forward and play/pause buttons. But you first must press the home button in order to access the Now Playing button on the CarPlay home screen.

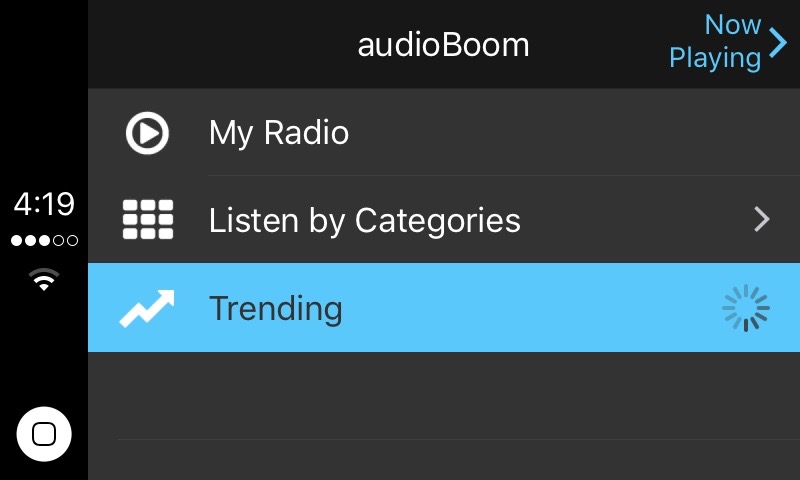

The Now Playing button is important because of third-party apps, which make CarPlay more of a menu maze. Some third-party apps are executed better than others, though CarPlay’s inherent simplicity doesn’t allow for dramatic variations.

CBS News annoyed me. I wanted to queue up Tim Cook’s 60 Minutes interview last month (just the audio, of course), but the app showed only episode dates, not subjects. Not helpful. And what’s the deal with the all-caps title?

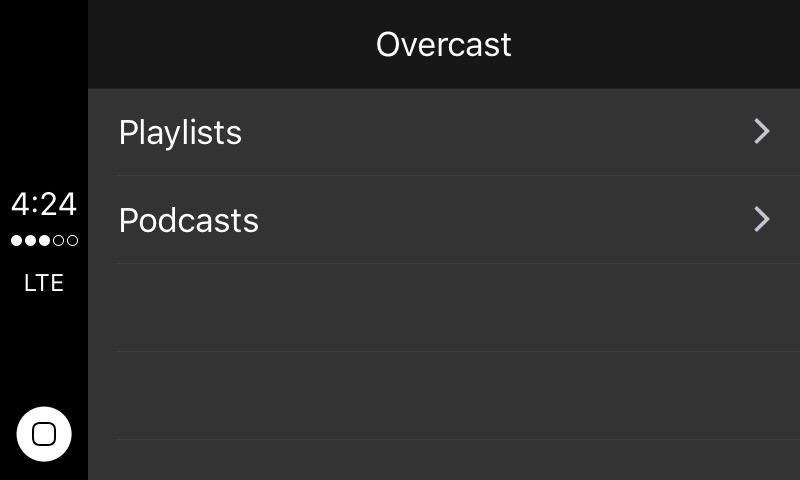

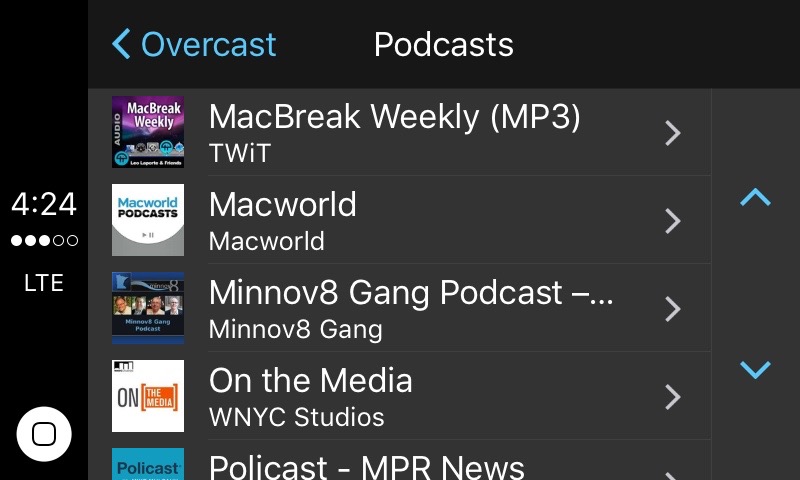

Marco Arment’s Overcast, not surprisingly, is more pleasant. The corresponding iOS and Web versions of Overcast are quite simple, so the minimalist CarPlay version isn’t jarring. Playlists and Podcasts are the only top-level choices.

Tapping Podcasts, I got a basic and easy-to-navigate show list.

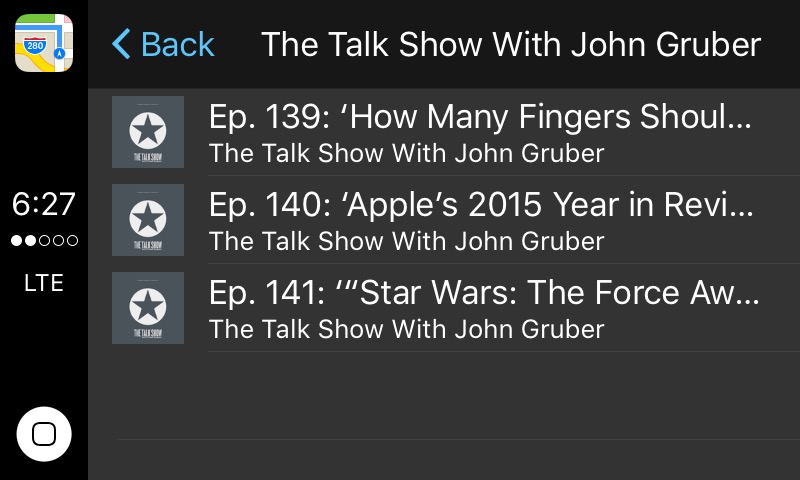

When I tapped one of the podcasts, Overcast pulled up that show’s most recent episodes.

CarPlay is important for iPhone-toting drivers because it offers choice in a variety of categories. Audiobook fans, for instance, not only score Apple’s Audiobooks but also Audible, AudioBooks.com, and Free Audiobooks.

At one point I was raptly listening to Isaac Asimov’s science-fiction masterpiece “The Foundation Trilogy” using Free Audiobooks without paying a dime. How cool is that?

Other third-party apps in my regular rotation included Stitcher for podcasts, Pandora for music, and TuneIn Radio — which I prefer over arch-rival iHeartRadio — for terrestrial radio streaming.

I have long been fond of TuneIn on mobile and desktop because of its ample audio selections, including music, audiobooks, podcasts, newscasts and more, along with its exemplary design. I was not surprised to find its CarPlay app has been executed impeccably.

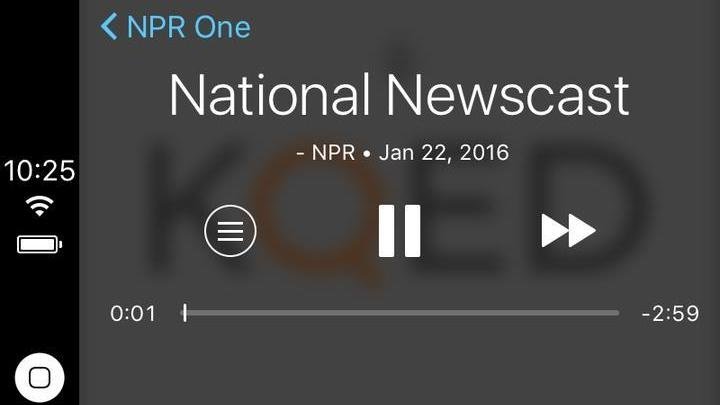

National Public Radio’s NPR One app was just updated to include CarPlay support.

NPR One’s CarPlay features include Catch Up to fire up the latest newscasts, Recommendations to scan a curated list of new stories and podcast episodes, Featured Shows listing top NPR and affiliate shows, and Followed to see favorited shows.

This is all great, but (as with other streaming apps, regardless of whether you use them on the iPhone or a car screen), keep an eye on your cellular usage to make sure you don’t end up with a giant bill.

CarPlay Problems — Using CarPlay, however, was an exercise in frustration at times… at least in my experience.

Glitches during my tests were all too common. Sometimes the apps threw up mysteriously blank screens.

Other times, apps would churn and churn for no apparent reason.

It was not clear to me whether such anomalies were app-specific or due to momentary interruptions in the data continually flowing to the iPhone via cellular or (less frequently) Wi-Fi connections. It could have been a bit of both.

Siri was another pain point. Activating it was simple enough: autos with integrated Siri typically include that steering-wheel button. You can also press and hold the CarPlay home button on the screen.

But my inability to make Siri do my bidding was stark, and I all but gave up on it. It misunderstood pretty much everything I uttered, even commands that Siri on my iPhone handled with aplomb. When I asked CarPlay’s Siri to pull up a 1980s New Wave playlist, for example, it kept offering me a Police playlist — same musical era, OK, but not what I requested. That’s confusing — why should Siri be any different? Plus, Siri can’t control third-party apps, which limits its usefulness.

Chevrolet offers its own voice assistant (which doesn’t have a name, as far as I know), and it worked better. That’s surprising — Siri is generally better than built-in systems.

Engaging in CarPlay-initiated phone conversations while driving also proved problematic since the person on the other end often could not make out what I said. That’s likely an indictment of the audio hardware in the cars, rather than of CarPlay, but it was still disappointing.

CarPlay isn’t executed identically by all car makers, and some have done a better job than others. In my test cars, for instance, I could have my messages read to me, but I couldn’t pick which ones. I’m told other auto makers give users more control, enabling drivers to see who texts are from and control which to read. Subject lines of email messages are provided, too.

In some vehicles, CarPlay can be controlled via knobs or buttons. This wasn’t true of my loaner vehicles, though it would have been a huge relief in some situations.

My bigger problem with CarPlay was my nonstop urge to switch back to my iPhone as my primary car interface.

Though smaller and a bit trickier to manipulate in a car cabin, the iPhone 6s Plus is a no-compromise device. The touchscreen is far better, all app features are available, and it’s generally easier for me to use after years of developing muscle memory with its various features. In some cases, it can be placed closer to me than the console-based touchscreens, too. It’s certainly possible for me to do things that I shouldn’t while driving, but I have sufficient self-control to abstain from such activities.

By comparison, CarPlay feels like a least-common-denominator solution in many respects, despite having been designed by Apple. Much of that is due to being simplified for safety reasons, and, no doubt, because the car-driving audience may be less technical even than novice iPhone or iPad users.

Should You CarPlay? — CarPlay remains a work in progress. Currently, it works only when the iPhone is physically jacked into a car USB port. Connecting via Bluetooth offers even more limited functionality, including Siri and phone calls, but the on-screen CarPlay features don’t work.

Wireless CarPlay is almost certainly coming. In fact, Volkswagen claimed it had wireless CarPlay to show at the recent Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas but said Apple put the kibosh on the demo — presumably since Apple wants to have its own unveiling in the near future.

CarPlay’s limitations raise the question: If you’re an iPhone user, and you’re in the market for a new car, should you make a buying decision based on whether CarPlay is or is not part of the package?

No. Buy the car you need based on other considerations, and if CarPlay happens to be included, it’s a nice bonus. Honestly, that’s a little depressing — I was secretly hoping that CarPlay would be so good that it would be something to seek out in a new car, or even a reason to want to buy a new car in general. Instead, I’ll just keep mounting my iPhone on my dash for now and we’ll see how many more miles I can get on the Mazda 5.

TidBITS Watchlist: Notable Software Updates for 25 January 2016

iMovie 10.1.1 — Apple has released iMovie 10.1.1, fixing a bug with YouTube sharing that could prevent sign-in for users with multiple accounts. The update also resolves a problem that could prevent White Balance adjustments from being applied to clips, ensures that Sony XAVC S clips captured at 100 fps or 120 fps play correctly, fixes a bug that could lead to incorrect display of still images, and now properly copies clips dragged from the Project Media container to events in the Library list. ($14.99 new from the Mac App Store, free

update, 2.02 GB, 10.10.5+)

Read/post comments about iMovie 10.1.1.

Parallels Desktop 11.1.2 — Parallels has released Parallels Desktop version 11.1.1 (build 32312), sorting out an issue with Boot Camp virtual machines not booting and fixing a problem that prevented NTFS drives from mounting. The virtualization software also resolved a bug with Microsoft Outlook crashing in Windows after opening an Outlook file from OS X, another crash that occurred after quitting a virtual machine in Full Screen mode while another virtual machine is running, and a bug that caused the mouse cursor to look corrupted when Retina settings were applied to an external display.

Shortly after this update was issued, Parallels Desktop was updated to version 11.1.2 (build 32408) to resolve an issue with connecting USB devices to virtual machines after upgrading to OS X 10.11.2 El Capitan, fix a bug that prevented a virtual machine from waking from sleep, sort out a problem with virtual machines not recognizing additional displays when using all displays in Full Screen mode, and prevent a black screen from appearing after installing Parallels Tools on 10.6 Snow Leopard and 10.7 Lion virtual machines. ($79.99 new for standard edition, $99.99 annual subscription for Pro/Business Edition, $49.99 upgrade, free update for version 11 licenses, 293 MB, release notes,

10.9.5+)

Read/post comments about Parallels Desktop 11.1.2.

Nisus Writer Pro 2.1.3 — Nisus Software has released Nisus Writer Pro 2.1.3 with a number of bug fixes for the venerable word processor. The update resolves an issue that could cause Nisus Writer to ignore the autosave delay preference, improves the CPU performance of the LibreOffice-based file converter when it should be idle in the background, fixes a crash caused by documents with certain kinds of automatic numbers, and fixes a problem with macros that failed to function correctly on OS X 10.11 El Capitan. ($79 new from Nisus Software and the Mac App Store, free

update, 221 MB, release notes, 10.8.5+)

Read/post comments about Nisus Writer Pro 2.1.3.

ClamXav 2.8.9 — Canimaan Software has issued ClamXav 2.8.9 with improved reliability of virus definition updates and the addition of a Quarantine toolbar button to the default toolbar. The virus scanner now checks proxy settings every time definition updates are checked, ensures that the Command-Delete keyboard shortcut deletes a selected file (rather than simply removing it from the infection list), improves reliability of scanning from the Finder Services/contextual menu item, and fixes a bug that prevented items added to the source list from getting properly selected. ($29.95 new, free update, 23.3 MB, release notes, 10.6.8+)

Read/post comments about ClamXav 2.8.9.

Security Update 2016-001 (Mavericks and Yosemite) — Apple has issued Security Update 2016-001 for OS X 10.9 Mavericks and 10.10 Yosemite with a single patch that affects the older California-themed OS releases. (The rest of the listed security fixes apply only to the concurrently released OS X 10.11.3 El Capitan; see “OS X 10.11.3 and iOS 9.2.1 Bring Bug Fixes,” 19 January 2016.) The update improves memory handling with libxslt (the library used to perform XSL transformations on XML documents) to avoid a type confusion that could allow a maliciously crafted to

execute arbitrary code. The security updates are available via Software Update or via direct download from Apple’s Support Downloads Web site. (Free. For 10.9.5 Mavericks, 288.3 MB; for 10.10.5 Yosemite, 369 MB)

Read/post comments about Security Update 2016-001 (Mavericks and Yosemite).

ExtraBITS for 25 January 2016

In this week’s ExtraBITS collection, the director of the National Security Agency defended encryption, a widow had to fight Apple to get her late husband’s App Store password, Apple released a new iOS app for musicians, and we got a preview of what iOS 9.3 will do for education.

NSA Director Defends Encryption — While FBI Director James Comey and Attorney General Loretta Lynch continue to rail against encryption, information security has gained another surprising ally: NSA Director Admiral Mike Rogers. During an address to the Atlantic Council think tank, Rogers said, “encryption is foundational to the future,” and cited the recent hack of the Office of Personnel Management as a reason to encourage encryption. “So spending time arguing about ‘hey, encryption is bad and we ought to do away with it’ … that’s a waste of

time to me,” Rogers said. Rogers’s predecessor at the NSA, General Michael Hayden, also recently spoke out in favor of encryption (see “Former U.S. Intelligence Director Favors Encryption,” 14 January 2016).

Apple Demanded Court Order from Widow to Recover Late Husband’s Password — Apple’s focus on privacy is good but can sometimes carry unfortunate consequences. 72-year-old Peggy Bush tried to download a game to her iPad, but didn’t know her late husband’s Apple ID password. Her daughter dealt with Apple support for two months, providing serial numbers and legal documentation before being told that Apple required a court order to resolve the situation. In fact, according to Apple’s terms and conditions, accounts are not transferrable upon death and Apple may even terminate the account.

Fortunately, Apple gave Bush access to the account after she reached out to CBC News and Apple CEO Tim Cook. This story illustrates why it’s important for families to have a plan for sharing key passwords, such as 1Password for Teams or at least a copy of 1Password’s master password in a safe-deposit box.

Apple Releases Music Memos for iOS — Apple has unveiled a new free app for musicians: Music Memos for iPhone and iPad. Unlike the built-in Voice Memos app, Music Memos is tailored toward musicians, with features like auto-record, backup players, and a pitch tuner. It’s a simple tool for quickly grabbing a recording to send to GarageBand or another audio-editing app.

iOS 9.3 Adds Features for Education Market — At MacStories, Fraser Speirs takes a look at new education-oriented features slated to appear in iOS 9.3. These features include a Shared iPad capability, a Classroom app for teachers, and Managed Apple IDs (via an Apple School Manager portal). With this upcoming release, Apple is both renewing its education focus in a big way and attempting to goose iPad sales, which have slowly but steadily declined in recent quarters. In education, in particular, Apple is worried about Chromebooks, which are cheaper, easier to share, easier to deploy, and have

keyboards.