#1495: Examining 5G health concerns, location privacy abuses, Apple Music Replay, and Smart Battery Case camera button

Welcome to the first issue of TidBITS for 2020! Curious about which Apple Music tracks you listened to the most in the past few years? We show you how to access the buried Apple Music Replay feature in the Apple Music Web app beta. Apple’s Smart Battery Cases for the iPhone 11, 11 Pro, and 11 Pro Max have a new feature: a camera button that you can press to take pictures—we have the details. The New York Times has published an exposé about how a secretive set of companies track our every move via our phones; we point you to that essential reading and provide tips on how to guard your privacy. Finally, Glenn Fleishman examines the health concerns surrounding 5G wireless networks and explains why you don’t need to worry. Notable Mac app releases this week include ChronoSync 4.9.7 and ChronoAgent 1.9.5, OmniFocus 3.4.5, GraphicConverter 11.1.2, Audio Hijack 3.6.3, CleanMyMac X 4.5.2, Luminar 4.1, Bookends 13.3, and Pixelmator Pro 1.5.5.

Here’s How to Access Your Yearly Apple Music Replay Playlists

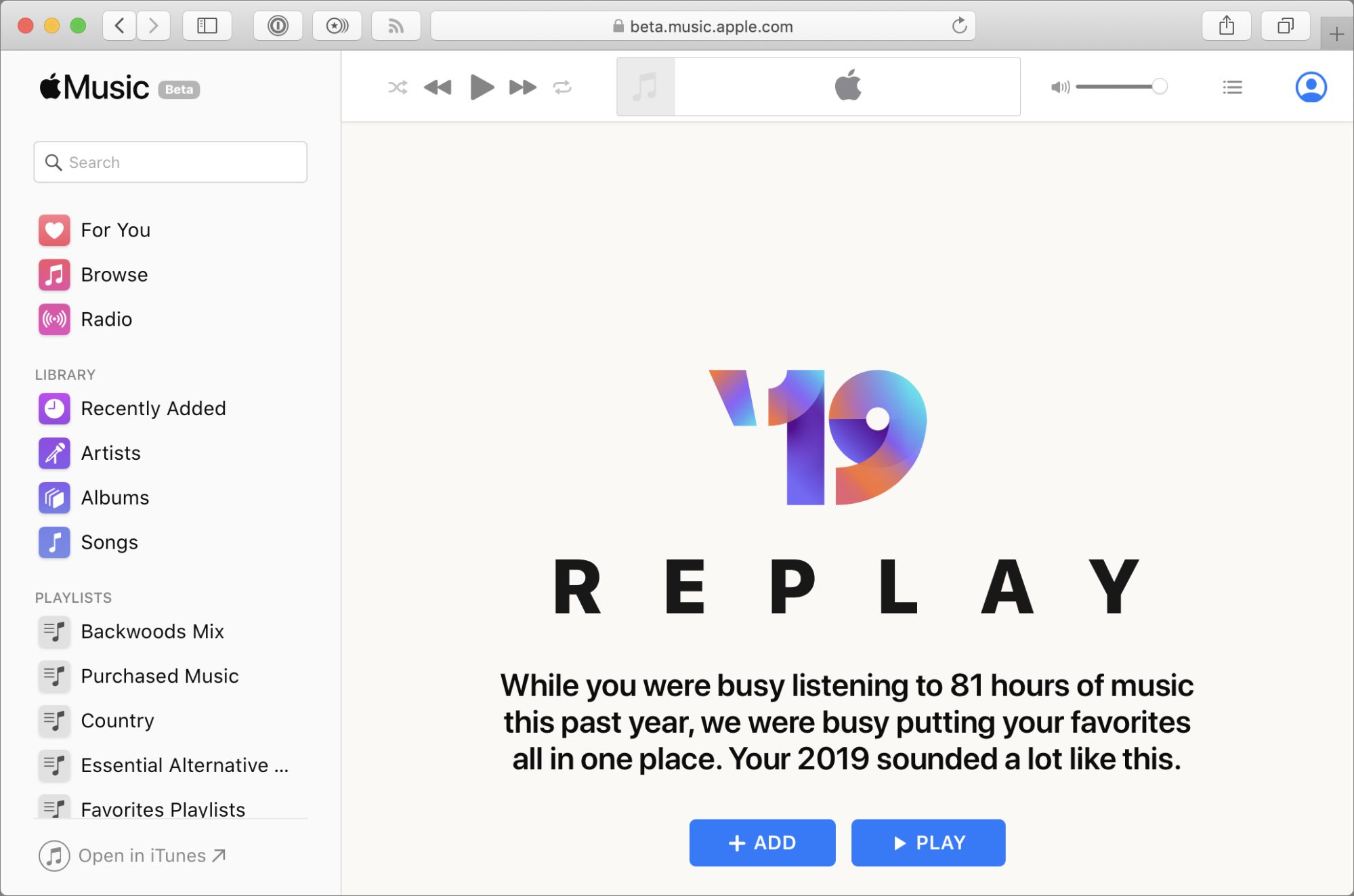

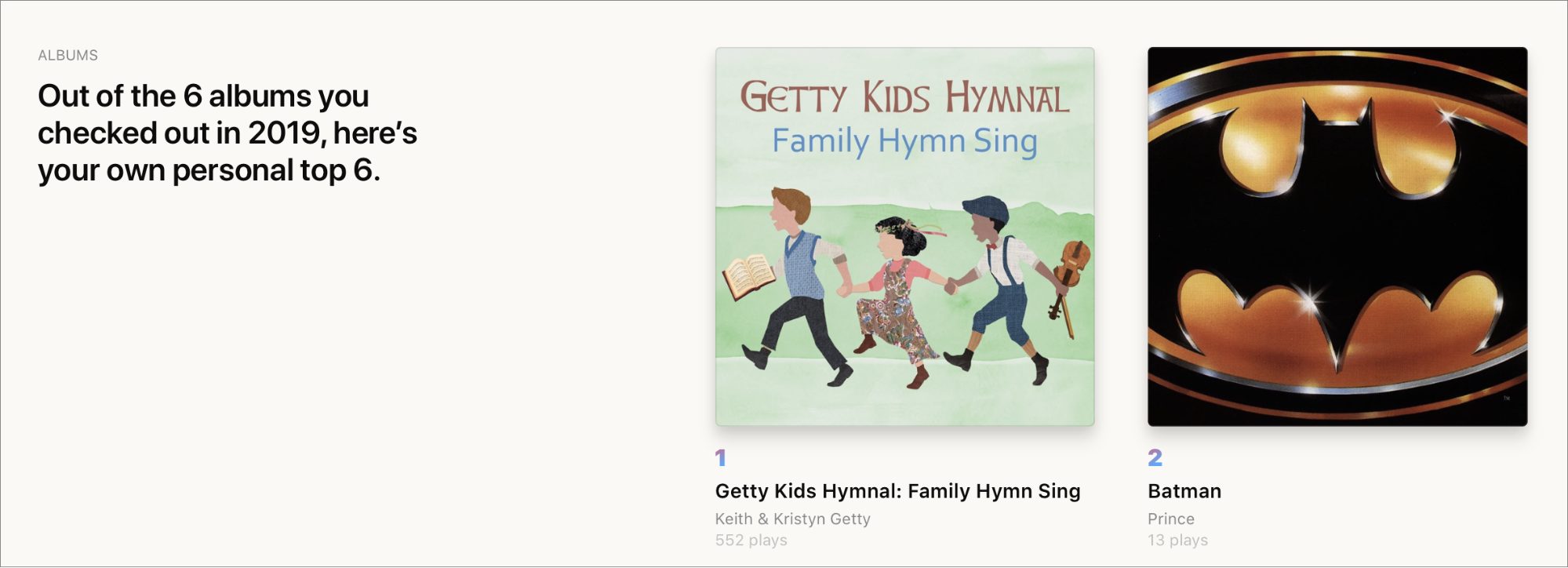

Wonder what music you listened to last year? Apple has quietly added a year-end-roundup feature to Apple Music, called Apple Music Replay, that details your most-listened-to artists, albums, and songs, and offers a playlist of your most-played songs from every year you’ve subscribed to Apple Music. Oddly, it’s not accessible via iTunes or the Music app.

Instead, you need to use the Apple Music Web app (see “Apple Launches Beta of Apple Music for the Web,” 6 September 2019). Scroll down in the For You section until you see the Replay banner, or just click this link and log in with your Apple ID.

Replay gives you all sorts of interesting statistics about your 2019 listening habits. Mine are a little screwy from playing things that will put the baby to sleep.

Replay gives you all sorts of interesting statistics about your 2019 listening habits. Mine are a little screwy from playing things that will put the baby to sleep.

Have fun browsing the statistics, but the best bits may be the Replay playlists. At the top of the Replay screen (see the first screenshot above), there’s an Add button to add your 2019 Replay playlist to your Apple Music library. Scroll down to the bottom, and you’ll find buttons to add Replay playlists from years past to your library. Each contains up to 100 of your most-played songs from that year.

Have fun browsing the statistics, but the best bits may be the Replay playlists. At the top of the Replay screen (see the first screenshot above), there’s an Add button to add your 2019 Replay playlist to your Apple Music library. Scroll down to the bottom, and you’ll find buttons to add Replay playlists from years past to your library. Each contains up to 100 of your most-played songs from that year.

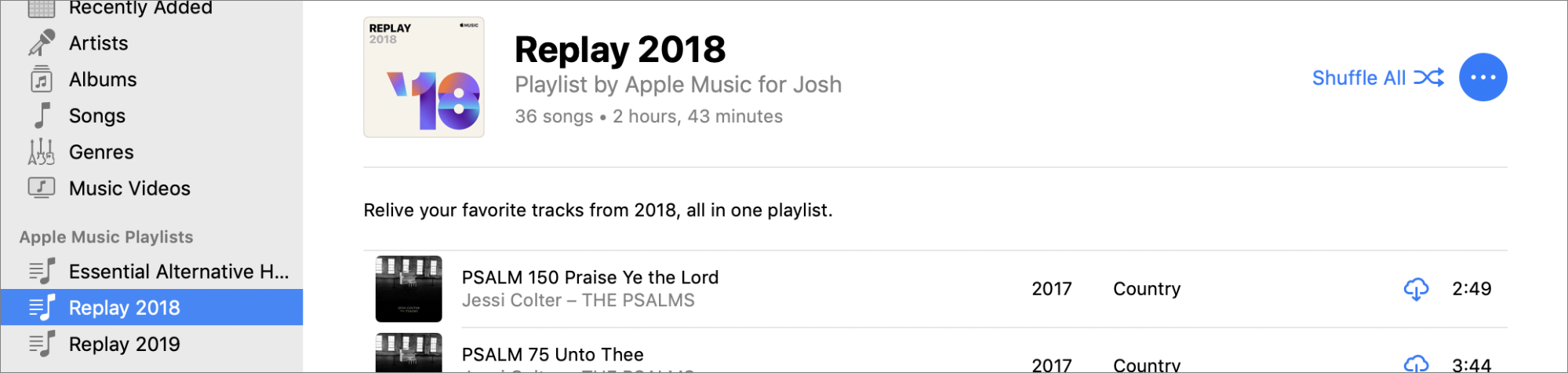

Once you add the Replay playlists to your library, they appear in iTunes and Music like any other Apple Music playlist.

Once you add the Replay playlists to your library, they appear in iTunes and Music like any other Apple Music playlist.

The iPhone 11 Smart Battery Case Has a Hidden Camera Button

Apple has released Smart Battery Cases for the iPhone 11, iPhone 11 Pro, and iPhone 11 Pro Max. All three cost $129, come in white, black, or—in the case of the Pro models—pink. Unexpectedly, they all have a slightly hidden and unusual feature: a dedicated camera button. The second paragraph of the Apple Store description reads:

The case features a dedicated camera button that launches the Camera app whether the iPhone is locked or unlocked. A quick press of the button takes a photo and a longer press captures QuickTake video. It works for selfies, too.

Cool, eh? I haven’t tried the case, but reports suggest that you need to press the button just a bit longer than you might expect would be necessary to take a photo. That slight delay, combined with the fact that the button is recessed, should reduce accidental snaps in your pocket.

How did Apple add an extra iPhone button to the Smart Battery Case, given that there’s no equivalent button on the iPhone? iFixit had the case X-rayed and learned that Apple added a small circuit board to the case that internally connects the camera button to the Lightning port. We’re curious to see if any third-party cases manage to reverse-engineer this button activation mechanism or if it’s going to remain proprietary to Apple.

How did Apple add an extra iPhone button to the Smart Battery Case, given that there’s no equivalent button on the iPhone? iFixit had the case X-rayed and learned that Apple added a small circuit board to the case that internally connects the camera button to the Lightning port. We’re curious to see if any third-party cases manage to reverse-engineer this button activation mechanism or if it’s going to remain proprietary to Apple.

Note that you need iOS 13.2 or later for the camera button to work. If you’ve followed our advice and kept iOS 13 up to date, this shouldn’t be an issue.

If you have one of these Smart Battery Cases, tell us how you like the camera button in the comments.

The New York Times Reveals How Completely Our Every Move Is Tracked

If it were up to me, I’d be nominating the New York Times article “Twelve Million Phones, One Dataset, Zero Privacy” for a Pulitzer Prize.

Anonymous sources provided the Times with a dataset from a single location data company that contained 50 billion pings from the phones of more than 12 million Americans over several months in 2016 and 2017. With the data, Times reporters Stuart A. Thompson and Charlie Warzel were able to track numerous people in positions of power, including military officials, law-enforcement officers, and high-powered lawyers. They were able to watch as people visited the Playboy Mansion, some staying overnight, and they could see visitors to the estates of Johnny Depp, Arnold Schwarzenegger, and Tiger Woods. Once they identified any particular phone, they could track it wherever it went. Imagine what that data could be used for in the wrong hands.

The Times has done an impressive job of showing both the scope of the data—with interactive images showing all the location pings at the Pentagon, for instance—and also diving down to the specifics, with a Microsoft employee who made an unusual visit to an Amazon office and a month later, took a job there. Might employers want to keep tabs on employees with access to confidential information? That’s just one example—the article includes others, some speculative, some not (like one random Los Angeles resident who was found traveling to roadside motels multiple times and staying for a few hours each time).

Go read the Times article and the additional pieces that the paper has published:

It’s a sobering look at just how little control we have over our privacy and how little oversight there is over an industry that knows more about us than our own families. Even if we assume good intent on the part of the companies collecting this data, there’s no guarantee it can be kept out of the hands of foreign governments or organized crime. The Times has put the spotlight on this industry; it’s up to us to make sure we convey our opinions of this situation to our elected representatives.

What You Can Do to Protect Your Privacy Now

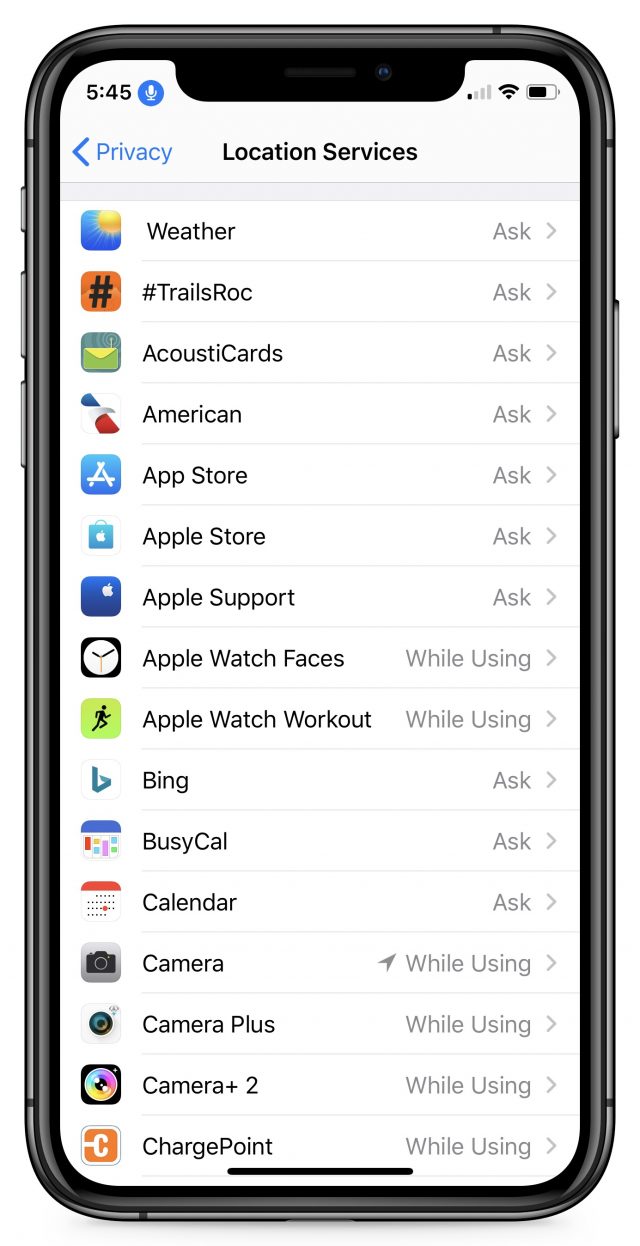

In the meantime, go to Settings > Privacy > Location on your iPhone and set every app to Ask Next Time unless you know what it’s doing with the location data. For instance, the Camera app needs the While Using the App setting to geotag your photos, and Maps needs it to give you directions. The Ask Next Time setting ensures that you’ll get a chance to decide the next time you actually use the app. Also, set any apps you don’t (or shouldn’t) trust, like Facebook, to Never, and make sure no app is set to Always unless you trust it implicitly. You might be surprised by which apps want to track you and which are set to Always.

In the meantime, go to Settings > Privacy > Location on your iPhone and set every app to Ask Next Time unless you know what it’s doing with the location data. For instance, the Camera app needs the While Using the App setting to geotag your photos, and Maps needs it to give you directions. The Ask Next Time setting ensures that you’ll get a chance to decide the next time you actually use the app. Also, set any apps you don’t (or shouldn’t) trust, like Facebook, to Never, and make sure no app is set to Always unless you trust it implicitly. You might be surprised by which apps want to track you and which are set to Always.

There’s no guarantee that restricting your location sharing settings will prevent these companies from tracking your location because there’s no way to know which apps are abusing their privileges (well, other than weather apps). The only way to be certain it’s not happening would be to turn off location services entirely, but that would severely reduce the utility of the iPhone. Even setting every app to Never would be problematic, eliminating Maps and Google Maps, Lyft and Uber, and photo geotagging in all camera apps. That’s why we recommend the approach above—everyone’s level of concern will differ, and only you can determine how perturbed you are by this tracking.

Worried about 5G and Cancer? Here’s Why Wireless Networks Pose No Known Health Risk

Can cell phones or Wi-Fi give you cancer? The answer is reasonably definitive: No. That’s equally true for new 5G cellular networks currently being rolled out worldwide, all previous cellular networks, and all versions of Wi-Fi.

Decades of research make it clear that the use of wireless networking, whether through mobile phones or Wi-Fi devices, carries with it no elevated risk for cancers or other diseases in humans. Some studies with rodents have garnered attention, but in a recent much-cited one that delivered a mix of results, some rats lived longer under high exposure to cellular signals than their control group counterparts.

It can be hard to accept that there’s no conspiracy here. Corporations and governments routinely engage in misdeeds, and that has instilled mistrust in many of us. It’s easy to become cynical and worn down, and to lump all concerns into the same basket when giant pharmaceutical companies sell drugs like Vioxx and OxyContin that they know have significant side effects (including premature death) as prescribed; when firms dump poison into communities, deny it, and then walk away paying nothing; and when city governments knowingly allow unsafe levels of lead in municipal drinking water.

People also tend to try to find a pattern of conspiracy where none may exist. It makes for good headlines. The Bloomberg News story in October 2018 about Chinese intelligence agencies installing spy chips on motherboards used in data centers by Apple, Amazon, and others produced a lot of noise but was full of inconsistencies and was categorically denied by all parties. Over a year later, nothing in the story has been expanded on by Bloomberg or confirmed by security experts, other reporters, or, well, anyone.

More recently, the Chicago Tribune published the results of testing from a firm it had hired to check if emissions from modern smartphones truly fell below FCC safety limits. In those tests, many appeared to exceed regulatory limits. The Tribune didn’t overstate its results, but the bottom line more or less suggested that smartphone makers were deceiving the FCC and the general public. This plays into our fears, even though the work was presented rigorously. (Smartphone makers dispute the methodology of the testing; the Tribune stands by its research. Regardless, there’s a big difference between detecting higher-than-approved emission levels and proving a link between those levels and cancer.)

But the potential of an increased risk of cancer and other diseases from routine exposure to electromagnetic fields (EMFs) used for cellular and Wi-Fi networks falls into a different category than other risks. The principles behind EMFs are founded in well-understood physics. Safety issues surrounding EMFs, particularly the ranges used in cellular networks and Wi-Fi, have been studied since the invention of radar in the 1940s—and science learned powerful lessons from early overexposures that led to injury and sometimes permanent disability or death among soldiers and technicians.

Fast forward to the present, and many people have expressed fear that the deployment of new 5G networking hardware introduces a new kind of risk. To achieve the promised high rates of speed and serve new categories of devices, 5G networks will draw from a much broader range of frequencies, some far higher (or shorter) wavelengths than current technologies. And many more base stations will need to be deployed.

But the newness and differentness of 5G don’t matter. Whether we’re talking about 5G, 4G, 3G, Wi-Fi, or other consumer-level wireless technologies, the sum total of results from many studies and many years of research paints a straightforward picture—there’s nothing to worry about.

Let me explain why wireless technology and associated industries aren’t like drug and tobacco companies, break down why you have nothing to fear from EMFs, why the Tribune may have gotten it right without their results being anything to fear, and how to evaluate the evidence.

A Global Industry Has Many Competitors, and Many Researchers

Many companies and industries that have perpetuated fraud and other crimes against the populace can typically do so because they have amassed enough power to control information about what they produce now or once made, all while keeping government oversight and checks on that power at bay.

The cellular industry certainly has influence around the globe, especially in the United States. And companies that sell Wi-Fi and Bluetooth gear ship billions of dollars of products worldwide.

Yet both groups—which have some overlap in chipmaking and mobile phone handsets—are diffuse. No single company controls cellular or Wi-Fi technology. It’s a broad mix of patent holders, chipmakers, hardware manufacturers, and—with cellular—network carriers. Thousands of companies compete for market share across all the different technologies. Plus, the network protocols in play are designed and promulgated by non-profit groups made up of representatives from numerous companies.

Further, the actual hardware in use is readily available, and the specifications governing that hardware and associated protocols are all public. The industry relies on widespread and well-understood technology.

Because of that, there’s another facet to consider: the networking world has no central point of control, whether a company or cabal, and no restriction on testing and publishing results, as the Chicago Tribune report made clear. Thousands of research studies of all sorts have taken place worldwide. Academic institutions, private organizations, government agencies, and media outlets have all carried out tests that range from simple hardware measurements to decade-long epidemiological projects that involve hundreds of thousands of people.

Could research be tainted? Certainly—in the US, there’s often a fear that universities don’t wish to risk corporate funding by publishing negative research, and many people have entirely valid concerns that state and federal agencies are captive to industries they regulate. However, in other countries, particularly in the European Union, governments and nonprofits fund research and either limit corporate involvement or ban it altogether, and are willing to act forcefully against firms, even if there’s an economic cost. In reality, industry groups have sponsored only a relatively small fraction of wireless research, and even then, some of it generated inconclusive outcomes or provided unsatisfying or unfavorable results to their business interests.

I would be overstating the case to say these facts about wireless research guarantee that no coordinated conspiracy exists to suppress information about widespread health risks. But it’s highly unlikely—there’s too much transparency.

Also, wireless communications technology is now so ubiquitous that there’s a vast amount of exposure to examine and plot data against previous generations when evaluating cancer and other kinds of ailments. The past is a control group.

Even if there were a conspiracy, if the health risks over EMF exposure were elevated, researchers would see the results across huge swaths of the world, which hasn’t happened.

If that’s so, why do some people point to EMFs as the problem? It has to do with history.

EMFs Are an Easy Target for Ill-Defined Conditions

Every few years, as people attempt to find a cause for random disease clusters and inexplicable health problems, EMFs are held up as a possible culprit. It’s part of being human that we look for patterns, and often create them when none exist. (Look at both extremes of contemporary politics everywhere in the world!)

In 1979, a study connected increased incidence of childhood leukemia to living near high-voltage power transmission lines. This single study—call it Patient Zero—is likely the origin of the fear of EMFs causing cancer. However, dozens of studies since have been unable to find strong correlations, although some show that kids living extremely close to high-voltage power lines might have slightly increased odds of developing leukemia.

But there are three substantial missing pieces in the discussion:

- First, very few children—defined for this disease as newborns to 20-year-olds—contract leukemia. The rate in the US is 4.7 per 100,000 per year, or fewer than 4000 new cases each year.

- Second, of those kids, only a very small percentage live close to high-voltage power lines. Thus the number of possible additional kids contracting leukemia is no more than a handful each year, making it extremely difficult to associate the power lines with the disease directly.

- Third, scientists have discovered no biological mechanism that might explain an increased risk.

As a result, even those researchers who have found a correlation between high-voltage power lines and childhood leukemia are dubious that what they’re measuring has to do with power lines at all. In 2005, one researcher suggested that living near power lines is also correlated to something else that really does increase a child’s leukemia risk.

A 2018 paper in Nature reviewed dozens of studies over decades and determined that kids who lived within 50 meters (165 feet) of a 200 kilovolt or higher power line had a slightly elevated risk of contracting leukemia. But the researchers concluded that the intensity of magnetic fields couldn’t be the culprit—the intensity of the magnetic fields wasn’t high enough to explain the findings. (That’s partly because power line magnetic fields max out at about 2.5 microteslas when you’re directly underneath, whereas the earth’s magnetic field, to which we’re all exposed all the time, varies from 25 to 65 microteslas, 10 to 26 times higher.) “Reasons for the increased risk, found in this and many other studies, remain to be elucidated,” wrote the researchers.

Some researchers have speculated that “something else” is the kind of hygiene, nutrition, general quality of life, and chemical exposure conditions that exist in communities through which high-voltage power lines are allowed to cross. Wealthier people either don’t live under them or prevent them from being built nearby, long before any health risk was a concern.

If you have a population of poorer, sicker people with worse access to healthcare and food, and who may have a higher concentration of industrial contaminants in their neighborhoods, that might be a trigger for the conditions in the body that result in childhood leukemia. It remains speculation. (Frankly, this reminds me of the origin of the field of epidemiology: Londoners had many explanations for outbreaks of cholera, and it took the rigor of one person to convince others that well water was the cause.)

It may also be that the data about children’s ages, where they lived, and intensity of fields near the powerlines isn’t sufficiently accurate, and the elevated risk is entirely statistical noise. The field data used for the studies isn’t generally directly measured from any of the locations analyzed. Rather, it’s calculated from maps of powerlines, information provided by utilities or from public sources, and geographical information systems that map properties for municipalities. Given the distances and power levels involved, some of these numbers aren’t much better than guesses.

Similarly, some people have self-diagnosed a condition labeled electrosensitivity. Those who suffer from this putative disease say they experience fatigue, mental fog, and other debilitating symptoms when in the presence of EMFs, even at a great distance. They sometimes label the miasma of EMFs that they believe afflicts them as electrosmog.

Teasing out the cause of electrosensitivity is tricky because the environment around us is suffused with EMFs and signals. However, because of the “inverse-square law,” most of that is at levels of energy that can barely be distinguished from noise by the miracle of modern data-receiving radio equipment in Wi-Fi adapters and phones. The inverse-square law states that a signal decreases by the square of the distance—stand 1 foot away from a transmitter and get a power measurement of 100, whereas 2 feet away it will be 25, and so on. Even with a cell phone next to your head, the design points the signal away from you, and your skin and bone absorb quite a bit of it before it reaches the sensitive soft tissues in which cancers are most likely to form.

The New York Times noted in July 2019 that a widely circulated chart that purported to show the absorption of signals by brain tissue was never evaluated by anyone but its creator, a physicist without biological expertise. One prominent expert witness who relied on the chart in testimony for years admitted that he had no idea that skin blocked the passage of high-frequency signals in particular. “…maybe it’s not that big a deal,” he said.

Scientists have been unable to find any electrosensitive condition, which makes sense given it has no basis in which it could exist. In study after study—many double-blind and peer-reviewed—in shielded rooms to block outside EMFs and using EMF generators with known properties, people who believe they have this ailment are able to detect the presence or absence of signals at rates no better than chance and no better than control subjects.

But here’s the thing, and it’s crucial: Researchers who hooked people up to measure their physical response during testing found that they did experience a variety of ailments. It’s just that those ailments weren’t correlated with whether signals were present or not. These people have real problems, but these tests prove that EMFs are not the cause.

Oddly, as with powerlines and childhood leukemia, those who claim to suffer from electrosensitivity seem less concerned about other, more likely culprits for unusual health problems: massive pesticide exposures in food and the environment, prescription drug outflow into water supplies that wind up back in our bodies, and the dangers of microplastic exposure, the impact of which we’re learning more every day, to name just a handful of global health concerns.

Nonetheless, the obsession with EMFs has persisted.

Wi-Fi and Cell Signals: Same Song, New Refrain

In the 1990s, when I helped out on a book about ways to improve your health in an office, including better monitor position, ergonomics, and exercise, the author and I looked into research that alleged increased health risks from the extremely low frequency (ELF) and very low frequency (VLF) signals emitted by cathode-ray tube monitors.

Not surprisingly, the studies were poorly done and not reproducible, and as the population of users increased, the predicted increase in health problems didn’t happen. (One of the people pushing ELF/VLF health fears had spent many years doing the same thing with power lines.)

A decade later, while I was writing a daily blog, Wi-Fi Networking News, concerns about the effects of cellular networks and Wi-Fi base stations began to rise. These debates felt like the same lyrics with a new melody, but the number of people who would be exposed meant it was essential to study the issue with care instead of dismissing it. I took that tack, even though the physics of EMFs put out by Wi-Fi and cellular signals and known biological mechanisms meant a connection was implausible.

Once again, early studies on cellular use showed the potential of causation. Many used lab animals exposed to levels of EMF far above what people would ever experience and for long periods of time every day. Others used retrospective analysis, asking people to fill out surveys about past use, and then associated their answers with a corresponding health survey to look for an increase in rare cancers.

Just as with the power line concerns, as the years progressed and more studies were conducted with greater rigor, the potential effects disappeared. At the same time, with a large population of people using cellular phones and in regular proximity to Wi-Fi networks, specific health effects should have bubbled up in the population, showing increases especially with cancers and diseases that were otherwise uncommon. No such widespread health concerns appeared.

The fact is that Wi-Fi and cellular networks use exceedingly small amounts of power, far below the thresholds known to cause risk by exposure. Back in the 1940s and 1950s, when powerful microwave use in military radar and other purposes was just getting started, research helped understand the effects microwaves have on health, and limits were set with significant margins.

In particular, Wi-Fi and cellular networks, including 5G networks, use relatively high frequencies, which have short wavelengths. They don’t travel far and, the higher the frequency, the shorter the distance they can travel using the same power as lower frequencies. By deploying 5G densely, less power is needed, and by using high frequencies, it can’t penetrate far—whether through walls or into our bodies. Even though many more base stations will be deployed, they’ll be sending out far less power than today’s networking systems. (In comparison, the microwaves in early radar used longer wavelengths and lots of power, rendering them much more dangerous.)

Lies, Damned Lies, and Statistics

There’s no question that you can find seemingly compelling research results online that link aspects of some EMF studies with a potential increase in risk for certain cancers. Many of these results fall afoul of a modern scientific research problem that’s currently causing a massive upheaval across all fields in which data are gathered.

The problem is generally called “p-hacking,” where p refers to the standard measurement of probability. To say that research results are “statistically significant,” researchers need to find a probability of p < 0.05, which means that there is a less than 5% probability that the results happened by chance. No matter how slight the result, if p < 0.05, it can be cited as statistically significant.

Because of the pressure academics feel to publish and obtain grants, some scientists have unfortunately developed a habit of p-hacking for results by analyzing research data in ways other than those stated in the study’s hypothesis. This practice, though common in the business world, is increasingly considered illegitimate in science. A celebrity Cornell University professor’s lab engaged in this practice, according to Buzzfeed investigations, and he recently resigned after a number of his group’s seminal papers were retracted or corrected.

The emerging gold standard for research will likely involve stating the hypothesis to be tested at the outset and placing it in escrow—it would be like a fortune teller placing their predictions in an envelope held by a member of the audience—plus retaining raw data in a standardized form that others can analyze later. (These changes are all aimed at addressing the “reproducibility crisis,” the inability of researchers to replicate the results of earlier, sometimes seminal experiments.)

I read many studies in the 2000s in which the research appeared to look for one result, but failing to obtain it, sliced and diced the data to find something—anything!—that showed p < 0.05. These conclusions were often baffling, as they would demonstrate a noticeable risk for a sliver of, say, rats or people by age, gender, and exposure, but sometimes decreased risk for other, very similar groups. That’s the problem with p-hacking—you might stumble across something that’s p < 0.05, but simultaneously makes no sense, fits no models, and can’t be reproduced independently.

A good example is the 2010 Interphone study, which was initially heralded as a landmark set of studies conducted across countries. But the p-hacking of its results made it ripe for citing by skeptics and of dubious quality for those who work with statistics. One of the conclusions drawn from the study was that using a cell phone a lot apparently reduced the cancer rate in an odd demographic group of people, a result for which there’s no sensible biological explanation. The most likely explanation stems from design flaws in the study.

More recently, large-scale, long-term rat studies found nothing conclusive. The New York Times wrote a few times in 2018 about the rodent study I mentioned earlier. The study clearly demonstrated the risk of high levels of exposure that far exceed US safety limits. The catch is that the risk was evident only when the EMFs were applied to the full bodies of rats, not just the areas of our bodies that are exposed to EMFs. Oh, and male rats had a reduced risk of cancer. Moreover, the kinds of cancers these poor rats experienced haven’t increased in frequency in the human population, nor have they been found in studies that characterize cell phone users by heaviness of use.

Otis Brawley, chief medical officer of the American Cancer Society, told USA Today in regard to the new research, “The incidence of brain tumors in human beings has been flat for the last 40 years.” His organization has written up in a highly readable and sensible way the current understanding of the risks, complete with short analyses of key studies.

With no evidence of sensitivity, no increase in cancers, irreproducible studies that have led to dead ends, and no epidemic of conditions among the large, long-term population of cell-phone and Wi-Fi users, we’re led to one conclusion: There is no health risk associated with everyday exposure to common EMFs. That’s the case even if, intuitively, it feels like there must be a link. We may never get over that feeling, but we should base our behavior and policy on solid science, not feelings.

The good news is that, even if you’re still concerned, the inverse-square rule is your friend, as long as you accept physics. For those who worry about EMF exposure and can’t shake it, anxiety is obviously a legitimate condition, and one that you can mitigate. The American Cancer Society recommends if you remain concerned about EMFs and spend a lot of time talking on a cell phone, for your own peace of mind, use earbuds or keep the phone further away from your head.

And maybe don’t put your Wi-Fi router under your pillow.