#1608: How to test Internet responsiveness, Wordle takeoffs, understand cryptocurrency

This issue of TidBITS brings you a unique mix. In a helpful article that hearkens back to content we published 25 years ago, Adam Engst explains how you can use Apple’s new-in-Monterey networkQuality tool to get a more accurate picture of your Internet connection’s responsiveness, which is essential for video calls and gaming. For those who enjoy Wordle, Adam also explores numerous Wordle-inspired games, including multidimensional, adversarial, multiplayer, and non-linguistic variants. Finally, Glenn Fleishman delves into the thorny details of cryptocurrency to explain why it’s worth understanding the basics even though you shouldn’t invest in it. Our only notable Mac app release this week is Typinator 8.12.1.

Use Apple’s networkQuality Tool to Test Internet Responsiveness

Videoconferencing has revealed to all of us how good—or poor—our Internet connections really are. However, if you’re just loading Web pages or reading email, it’s unlikely you can get a sense of throughput. Even watching streaming video isn’t necessarily a good test, since it stresses only downstream bandwidth and streaming services use lots of tricks to avoid jitter and buffering. But because videoconferencing requires decent bandwidth in both directions, plus relatively low latency to keep the audio and video streams synced, it provides a clearer picture of your network quality. If your video calls stutter or freeze, your Internet connection might be at fault. But how to quantify that? And if necessary, how can you fix it?

There are numerous tools for testing Internet connection speeds. Ookla’s Speedtest may be the best known, and you can also turn to Google’s tool—search for “speedtest”—or Netflix’s Fast. All of those should provide roughly similar results for download and upload throughput, but those two numbers don’t tell the whole story.

Latency, which is often overlooked, can play a key role when bandwidth is otherwise sufficient for your purposes. (Speedtest calls latency “ping.”) Latency measures how many milliseconds it takes for you to get a response from the remote server. Low latency numbers are essential for smooth video calls and responsive gaming, though it’s difficult to connect a particular latency measurement with perceived performance. Is a 100-millisecond latency good or bad?

Unfortunately, latency numbers reported by standard speed tests may not accurately reflect what you’ll see in the real world, such as when someone else on your network is enmeshed in a Zoom call, watching a 4K video stream, or backing up to an Internet backup service. High-bandwidth activities can cause latency spikes that spell trouble for otherwise good connections for everyone on the network. In other words, we need to think about latency when our networks are under load, not when they’re idle.

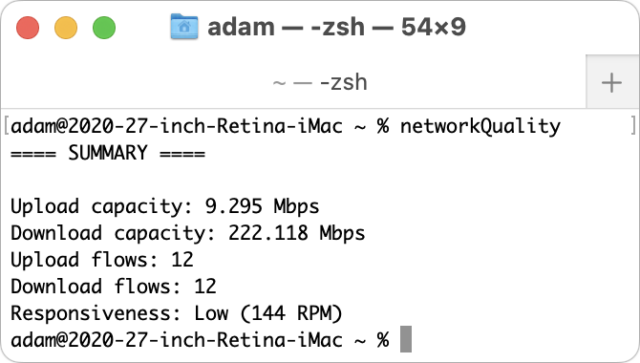

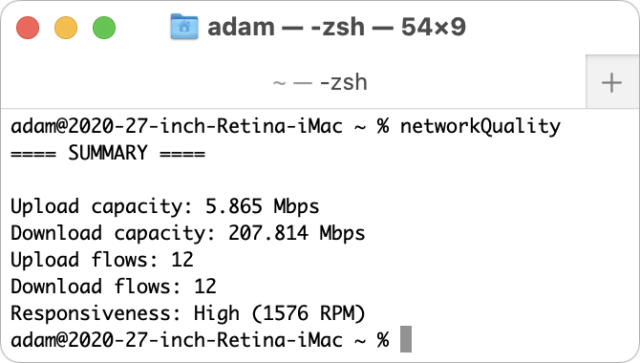

All that’s by way of introducing the networkQuality command-line tool that Apple introduced with macOS 12 Monterey. If you open Terminal and type networkQuality, it will report on upload and download “capacity,” which is a better term than “speed” because Internet connections are essentially pipes—the larger the pipe, the more traffic it can carry, just like a larger pipe can carry more water. You’ll also see numbers for upload and download “flows,” which are reportedly the number of test packets used for the responsiveness tests. (I usually see 12 there, though I once saw 20 for upload flows and, another time, 16 for download flows.)

Most interesting is “responsiveness,” which measures the number of roundtrips per minute (RPM) under load and attempts to provide a number that better measures the effects of latency without using a time measurement. Along with being a nod to the “revolutions per minute” measurement from car dashboards, RPM is a “higher is better” metric that’s easier to understand. Its numbers tend to be in the three-to-four digit range, making them easy to compare. Plus, Apple interprets the numbers for you, offering Low, Medium, and High labels. Here’s how the company describes those evaluations:

- Low: If any device on the same network is, for example, downloading a film or backing up photos to iCloud, the connection in some apps or services may be unreliable, such as during FaceTime video calls or gaming.

- Medium: When multiple devices or apps are sharing the network, you may experience momentary pauses or freezes, such as during FaceTime audio or video calls.

- High: Regardless of the number of devices and apps sharing the network, apps and services should maintain a good connection.

Our old friend Stuart Cheshire, who explained latency 25 years ago in a two-part TidBITS series, “Bandwidth and Latency: It’s the Latency, Stupid” (24 February 1997), worked on the RPM metric at Apple and introduced it in a WWDC 2021 video. (Stuart also wrote the interactive networked tank game Bolo many years ago and was responsible for the Bonjour zero-configuration networking project at Apple. Few people know networking like Stuart.)

As a command-line tool, networkQuality has a variety of switches that could be useful—type man networkQuality to see all of them. The tool’s options let you point at your own server instead of Apple’s and force the test to use a particular network interface (Ethernet instead of Wi-Fi, for instance), among other choices.

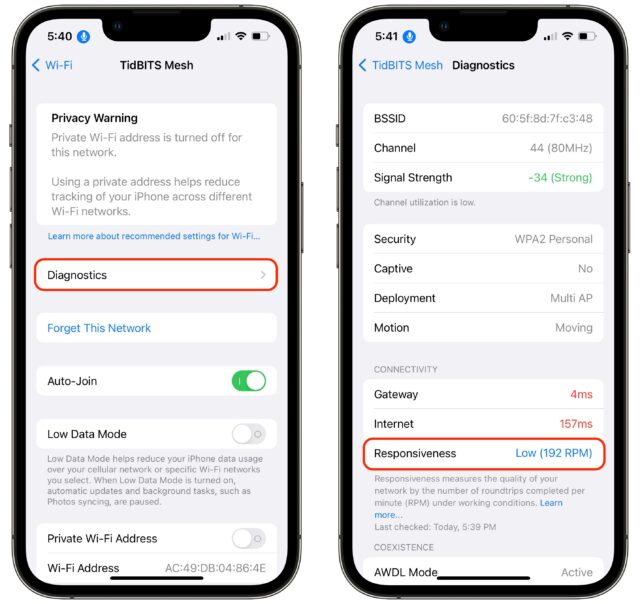

You might want to test responsiveness on your iPhone or iPad as well. Apple offers a WiFi Performance Diagnostics profile that those with Apple Developer accounts can install (see Apple’s support document for full instructions). Then go to Settings > Wi-Fi, tap the i button next to your network, and then tap Diagnostics and the Test link next to Responsiveness. (If you’ve already done one test, the Test link changes to the last result—tap that to run the test again.)

Apple’s latency measurement shows the company taking its own path once again, but, like Apple’s usual reasons for going its own way, the networkQuality responsiveness results better reflect your actual experience of latency. This new RPM metric isn’t proprietary—it’s an IETF draft with full details and even has open-source server code on GitHub. Wouldn’t it be great if these other tools took advantage of Apple’s work here to improve speed test results everywhere?

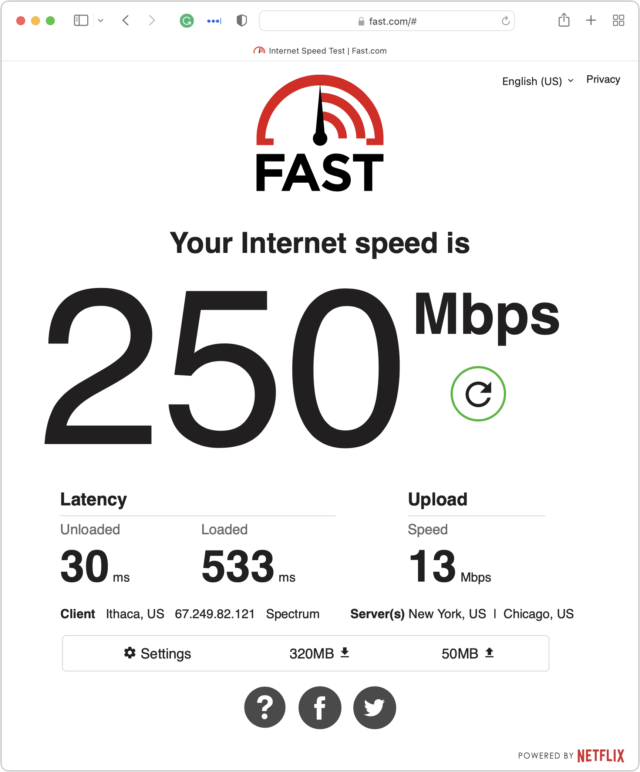

To be fair, if you click Show More Info after running a Fast test, it shows you latency results for both unloaded and loaded scenarios. As you can see below, my loaded latency is far worse (lower is better) than my unloaded latency, which corroborates my low RPM numbers from networkQuality.

What can you do about low responsiveness? More selfishly, what can I do about my terrible RPM numbers?!? I’ve been thinking that my 200+ Mbps downstream and 10+ Mbps upstream bandwidth was pretty good, and my raw latency numbers are always 30 milliseconds or below, which is great. But I’ve never found videoconferencing quality to be fabulous, though I’ve usually (and arrogantly, as it turns out) assumed that other people’s connections were at fault.

Apple’s networkQuality support page answers this very question, albeit somewhat generically.

If you’re using a Wi-Fi or wired network connection, some routers offer Smart Queue Management (SQM) to provide consistent high responsiveness, although these high-end home gateways generally require some expert manual configuration. The Apple Network Responsiveness test can be a useful tool for evaluating and comparing these home gateways, and it can be especially useful as a repeatable test when experimenting with different configuration settings and comparing the effects.

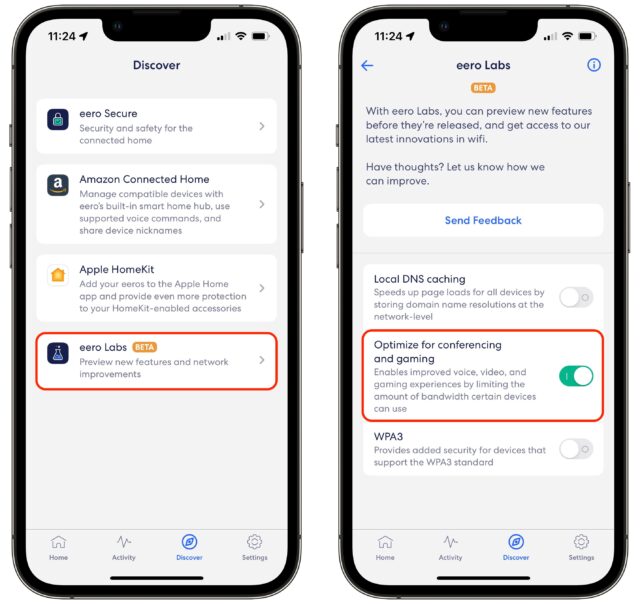

Some years ago, I replaced our Wi-Fi network’s increasingly flakey AirPort base stations with an Eero mesh system, and it has worked swimmingly. I can’t recall ever having to restart the primary Eero unit, something I had to do weekly with the AirPorts. (We’ve had connection glitches, but those are Spectrum’s fault and have nothing to do with the Eero system.) Some quick searching revealed that Eero has added a Smart Queue Management feature—called “Optimize for Conferencing and Gaming”—to its experimental Eero Labs settings. Since I’ve barely had to use the Eero app on my iPhone, I had to spelunk through every setting before I realized that Eero Labs has its own settings in the Discover tab. After that, it was trivial to enable Optimize for Conferencing and Gaming.

So did it work? Beforehand, my RPM numbers were always low, ranging between 89 and 144. After turning it on, they went stratospheric, ranging from 1315 to 1687! Fast’s loaded latency number also dropped by a factor of ten to 47 milliseconds. However, those are just numbers, and I won’t know for several weeks if it makes a noticeable difference in everyday video calls.

Alas, nothing is free in this world. When I was waiting for the iPhone screenshots above to upload to iCloud, I noticed it was taking longer than expected. That was unrelated, I think, but it caused me to look more closely at networkQuality’s numbers, where I discovered that my upload capacity had dropped by almost half, from roughly 10 Mbps to 5 Mbps. Tests through other tools also showed a reduction in upload bandwidth, though less extreme, generally dropping from 12–13 Mbps to 9–10 Mbps. I have no idea why enabling SQM would hamper uploads. In general, I’m willing to trade reduced upstream bandwidth for increased responsiveness, but it’s worth remembering that you can turn off SQM if you need raw upload performance.

Assuming, of course, that you can turn SQM on to start. As Apple notes, only some routers offer the feature, so you’ll have to research your particular router to see if it supports SQM and, if it does, how to turn it on. I recommend comparing network statistics before and after to see if it impacts your performance as it did mine. If you notice a real-world difference in videoconferencing quality, let us know in the comments.

Going Beyond Wordle: Oodles of *dle Games

Wordle has taken the Internet by storm. It skyrocketed from a handful of players late last year to millions today, with the New York Times acquiring the game from creator Josh Wardle for a reported seven-figure sum. Wordle gameplay is simple—every day, you have six opportunities to guess a randomly selected five-letter word. We explained it early in the year in “How to Play Wordle, the Word-Guessing Game of 2022” (7 January 2022).

Since Tonya and I are word people (and Tonya was a demon when playing the Boggle word game with her family growing up), we’ve taken to Wordle like definitions to a dictionary. Tonya decreed early on that we would always play separately, and no hints are allowed when one of us finishes before the other. (Though I must admit some glee in working subtle references to the answer into regular conversation throughout the day—she hasn’t yet connected any of those dots.) In contrast, my parents solve Wordle together every day.

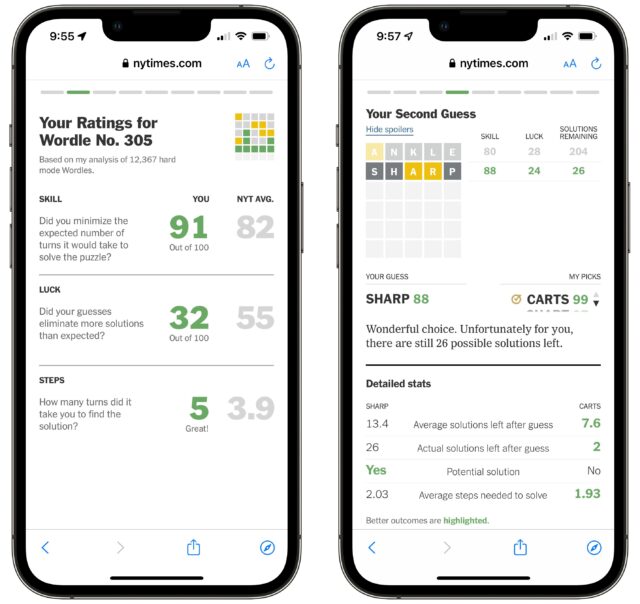

Early on, Tonya and I started wondering about our guesses. Were they skillful, or just lucky? Happily, the New York Times came up with WordleBot, which analyzes your guesses, sets them against how a bot would play, and gives you some statistics to compare if you’re a highly competitive type. It’s interesting background if you’re curious to peek behind the curtain. After you finish a game of Wordle, navigate to WordleBot in your browser to have it look at your results. (You can also upload a screenshot, but that’s fussy.)

WordleBot is frustrating to invoke if you, like me, created a Home screen icon for Wordle on your iPhone since Apple encapsulates the website so that it doesn’t share cookies with Safari. You can’t bring up the Safari address bar or bookmarks within Wordle’s saved Home screen icon to navigate to WordleBot after playing. It would be nice if the New York Times would add a link to WordleBot from Wordle itself—I’ve suggested it to them directly—but until that happens, here’s a workaround:

- At the end of your Wordle game, tap the hamburger menu at the top left.

- Tap the link at the bottom for “The New York Times” to go to the paper’s home page. Reading headlines at this point is not recommended.

- Tap the hamburger button at the top left of that page, and search for “WordleBot.”

- Tap the first item in the search results to load WordleBot.

The brilliance of Wordle is that it can be either easy or hard, depending on how well you can sort through possible words in your head. Some days, I can solve Wordle in a minute or two; other days, I must laboriously check numerous combinations of letters. I haven’t failed yet, but luck plays a role. I have gone down to the six-guess wire a few times when faced with multiple options for words that differ by only a single unknown letter. But no matter how long it takes, you’re done for the day once you enter the solution. Finitude is rewarding.

Unsurprisingly in today’s massively interconnected world, Wordle has served as inspiration for numerous similar guessing games. Some merely force all guesses to come from a limited set of words, but I find them uninteresting—my brain doesn’t segment words by category, so it’s frustrating to think of words that can’t work. A sampling:

- A Greener Worldle: words related to the environment and climate change

- Dundle: four-letter words associated with The Office

- Foodle: food-related words

- Gordle: last names of NHL hockey players

- Lewdle: naughty words

- Lordle of the Rings: five-letter words, including names, from the book

- Sweardle: the original four-letter words

- SWordle: Star Wars words

- Taylordle: a Taylor Swift-themed Wordle clone, however that works out

More interesting are the guessing games that change the concept or ask you to guess something other than words. Here are some we’ve tried.

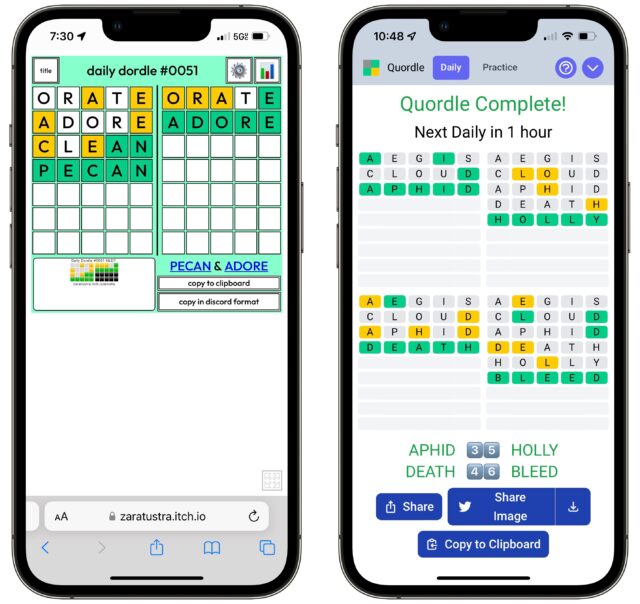

Dordle, Quordle, and Octordle

Whether it’s the old Qubic three-dimensional Tic-Tac-Toe game or Kirk and Spock playing 3-D chess in the original Star Trek, there’s something compelling about multiple interrelated game boards. Dordle, Quordle, and Octordle let you play two, four, or eight games of Wordle simultaneously, with each guess filling in the appropriate letters on each board. You get more guesses, too—7, 8, and 13, respectively.

These games are harder, needless to say, and can benefit from a strategy that plays as many letters as possible early on. But they aren’t as hard as they seem because a guess that tells you little on one board may be extremely useful on another. Tonya plays Quordle regularly—I play only sporadically. We usually win, but failure does happen. If you’ve found Wordle too easy, try one of the multiple board variants.

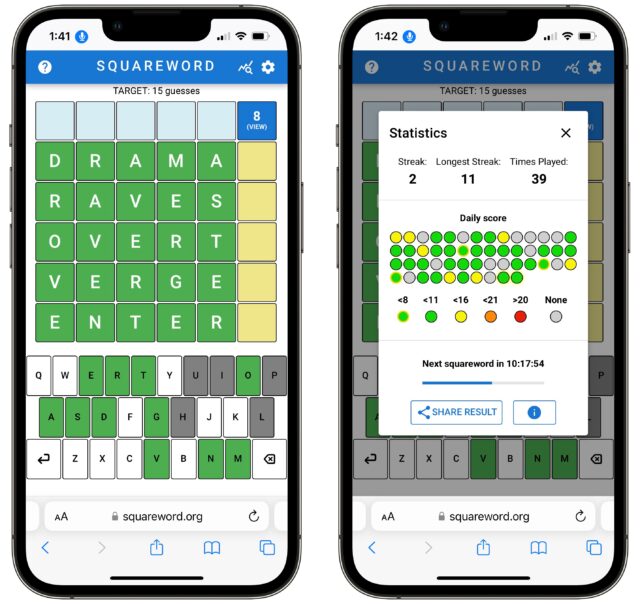

Squareword

As long as I’m invoking childhood board games, there was also Connect 4, which challenged players to connect four discs in another version of Tic-Tac-Toe. I thought of it the first time I encountered Squareword, which uses Wordle gameplay on a five-by-five grid. You try to guess the horizontal words, but all the verticals must also be valid five-letter words. Needing to complete the vertical words adds a nice fillip to the game, which challenges you to solve the puzzle in less than 8, 11, 16, or 21 guesses—there’s no limit to the number of guesses you can make.

We consider seven guesses to be “winning,” and it’s hard since you have to complete each horizontal word, which usually entails five guesses. It’s possible to do it in fewer guesses if you can work a necessary completion letter for one word into the right spot in another, but that’s uncommon. My main irritation with Squareword is that its indication of a <8 score is a green circle with a yellow ring, making it nearly indistinguishable from the pure green <11 score. Why not blue or something completely different?

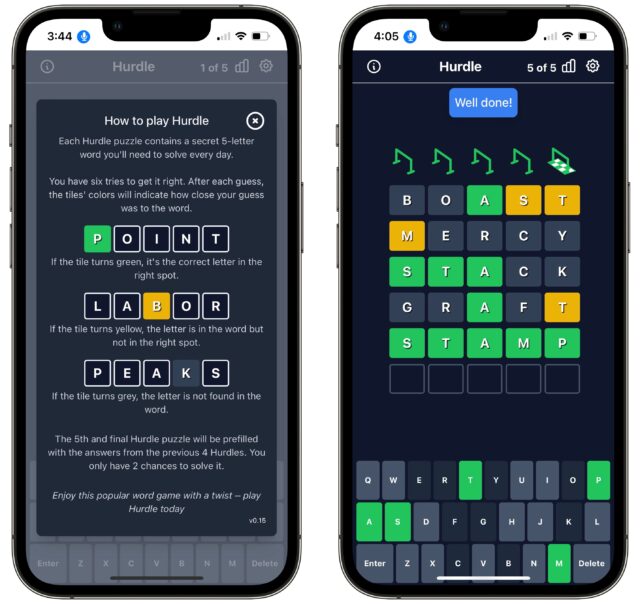

Hurdle

Rather than make you play multiple Wordle games simultaneously, Hurdle forces you to play five games sequentially. The twist is that the solution from each of the first three boards is used as the first word for the next board, and the fifth and final Hurdle board will be pre-filled with all the answers from the previous four boards, giving you only two guesses to arrive at the solution. Losing the option to specify your first word isn’t a problem, but being limited to just two guesses on the final board can be tough.

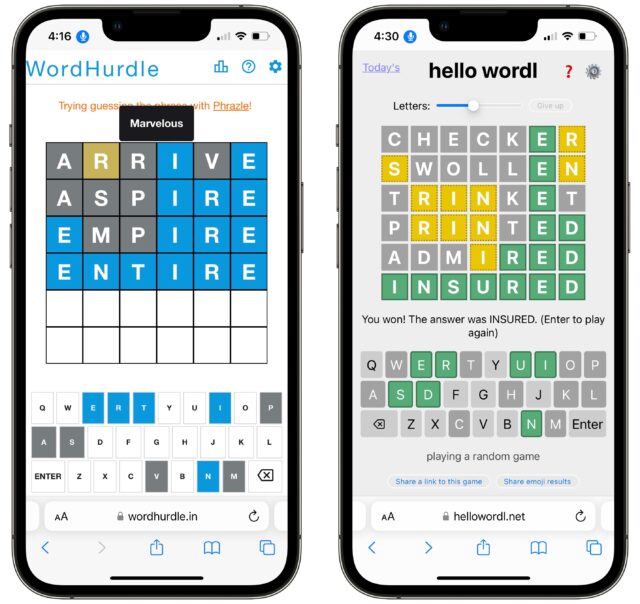

WordHurdle, More Wordle, Hello Wordl, Speedle

If Wordle’s five-letter guesses and answers are too easy for you, give WordHurdle, More Wordle, or Hello Wordl a try. WordHurdle switches to a six-letter grid and keeps the number of guesses at six. More Wordle offers three modes accessible from its gear menu: Easy (five letters, six guesses, just like Wordle), Medium (six letters, seven guesses), and Hard (seven letters, eight guesses). Hello Wordl is even more flexible, allowing you to choose games that employ anywhere between 4 and 11 letters, but it keeps the number of guesses at six. Speedle forks Hello Wordl to let you play multiple timed games in a row with numerous customizable options.

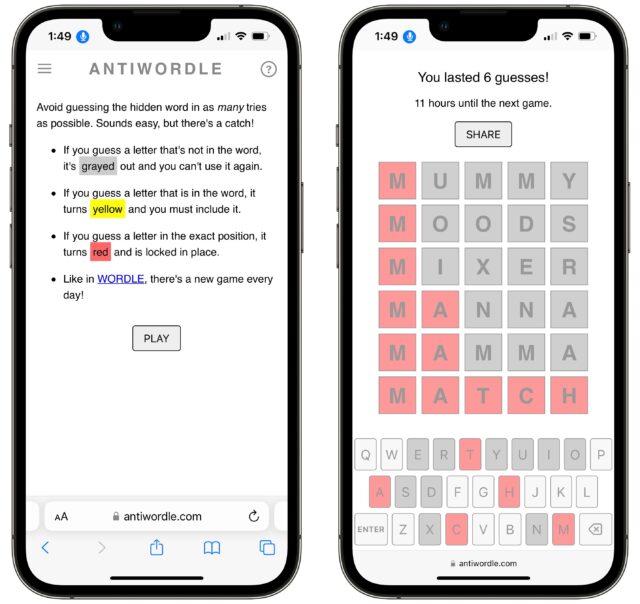

Antiwordle

Try not to think of a penguin. I suspect that as soon as you read the word “penguin,” an image of a thoroughly amusing flightless waterbird waddled into your mind. In another crowd, it might have been Tux.

That’s roughly the idea behind Antiwordle—you have to play Wordle while trying to avoid guessing the final word. Like Squareword, you have unlimited guesses; unlike Squareword, the more guesses you make, the better you’ve done. Tonya’s best game required nine guesses, and mine needed seven; it’s hard to progress past six. Perhaps it’s another way I’m bad at Zen, but I don’t enjoy thinking of something that’s not.

Antiwordle requires a completely different strategy since you want each guess to use as few letters as possible, thus leaving open as many options as possible. MUMMY, CIVIC, and TOOTS are all good words that consume only three letters each. However, once your letters start hitting, you’re in straight Wordle-land, and luck plays a larger role. If you get to letters like SHA_E, you might be able to draw out the game by guessing SHAVE, SHAME, SHARE, SHAPE, SHALE, SHADE, and SHAKE in an order that winnows out everything but the final answer.

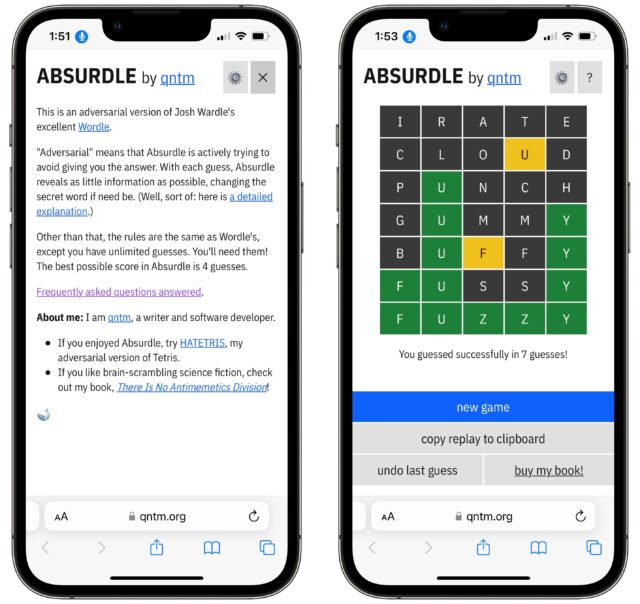

Absurdle

If you want even more human-on-bot competition than Antiwordle offers, try Absurdle. Unlike all the Wordle variants discussed so far, Absurdle doesn’t know the answer in advance. Instead, Absurdle evaluates your guesses and tries to reduce the set of possible answers as little as possible. It’s adversarial Wordle—Absurdle is actively working to stymie your efforts to get to an answer.

Of course, you will eventually be able to corner Absurdle and force it to admit defeat; the question is now many guesses you’ll have to employ to extract the answer. I mostly play Absurdle when I’ve had a bad day and want to take out my irritation on an uncomplaining bot.

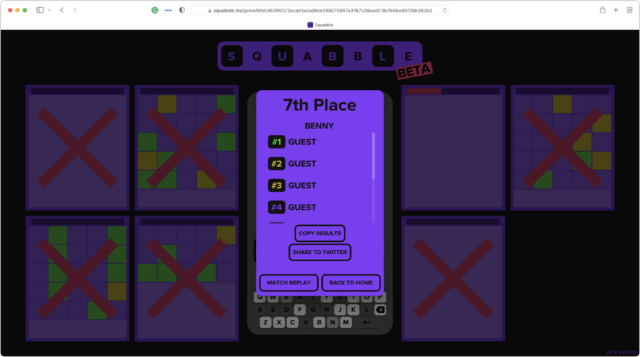

Squabble

Who needs bots when you can take on other humans in multiplayer Wordle action? That’s the idea behind Squabble, which lets you solve Wordle puzzles in two competitive modes: Blitz and Squabble Royale. In Blitz, you compete with 2–5 players; in Squabble Royale, you’re battling with 6–99 players. Squabble is anything but relaxing since correct guesses deal damage to other players, whereas incorrect guesses cause you to take damage. Plus, you take 1 damage point every second, so you want to guess right quickly. I’ve only tried Squabble a couple of times—I don’t need that kind of stress in my life. Squabble works only on a large-screen device, and I can’t imagine playing it without a keyboard.

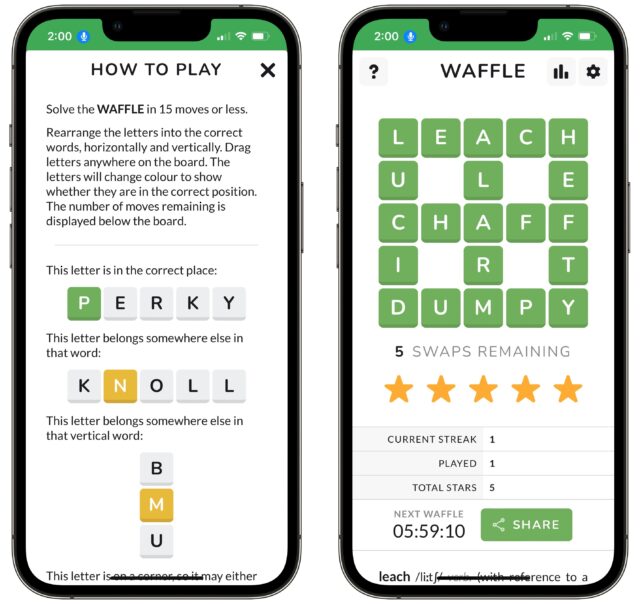

Waffle

Waffle looks like Squareword, with a five-by-five grid, although Waffle has four holes in the grid, resulting in just six words to guess. Instead of making you guess from scratch, Waffle provides all the letters you need, marking the ones in the right place in green and those in the wrong place in yellow. Rather than type words, you drag the letters around, swapping a white or yellow letter for another one to complete all the words. Every Waffle game can be solved in 10 moves and must be solved in 15; you get stars for however many moves you have left once you’re done. I find Waffle more relaxing than the traditional Wordle gameplay because it’s more about seeing patterns than searching through my internal word list for matches.

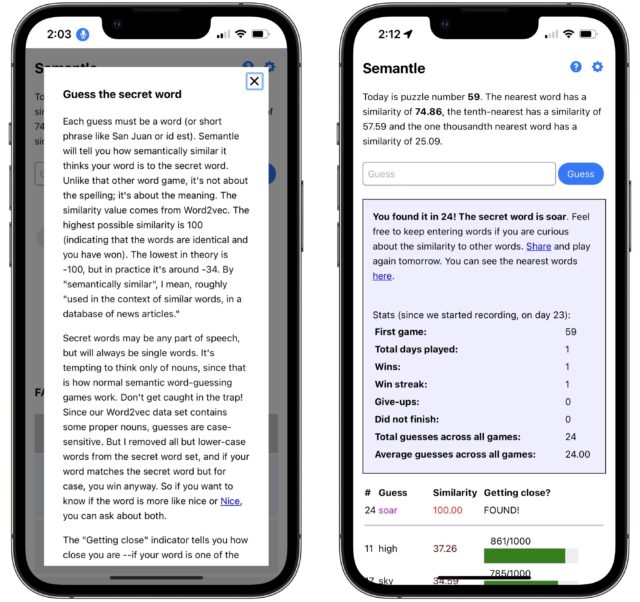

Semantle

And now for something completely different! Semantle comes up with a target word every day, but unlike all the previous games, you find it by guessing semantically related words. For each guess, Semantle tells you how close you’re getting with a numerical score. There are no limitations when it comes to the type of word or part of speech, so if the word is QUIET, guessing WHISPER might be somewhat close, but SILENT will be even closer.

The problem with Semantle is that it can take quite some time as you throw random words at it to get started. My fastest solution was 24 guesses, but I had another one that took 144 guesses and was really starting to get on my nerves.

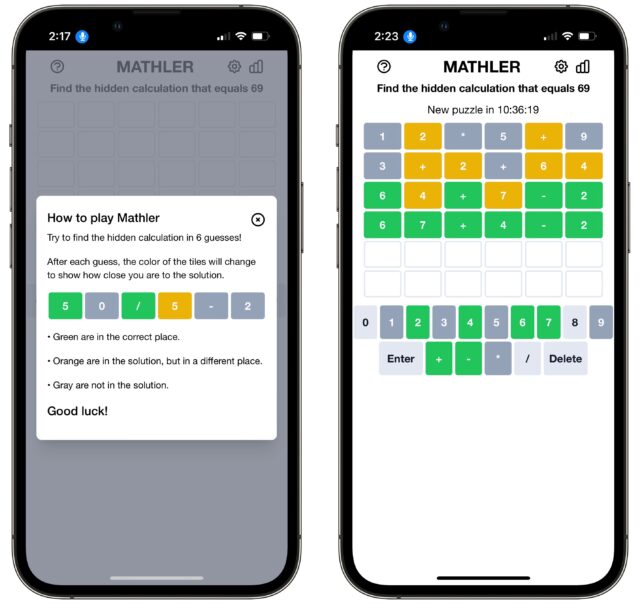

Mathler, Nerdle

If you think better in numbers than words, you can count on Mathler and Nerdle for a good time. Mathler gives you a number and asks you to write an equation to solve it while staying within the basic Wordle rules. Nerdle ups the ante by requiring you to figure out the entire equation, including the equal sign. Order of operation matters, so you have to multiply and divide before adding or subtracting. Mathler is a little easier since you know where you’re going. I can solve these puzzles, but as someone who has always preferred words to numbers, I don’t inherently enjoy the process.

Worldle, Globle

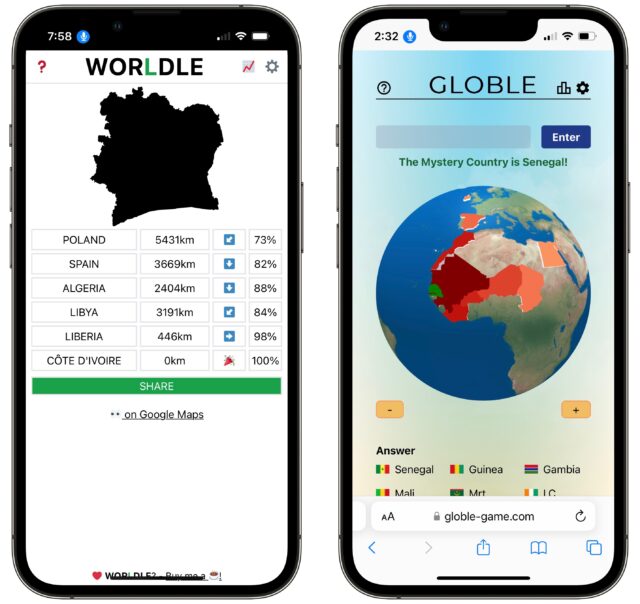

Worldle gets points for double wordplay, given that it roughly follows Wordle rules but translates everything to an image matching game where the images are those of countries or territories. How well do you know your maps? As you guess—helpfully, Worldle auto-completes country and territory names—Worldle gives you a closeness score of 1 to 5 and tells you how far off you are in kilometers and direction, with an arrow pointing toward the answer. Try to home in on the answer in six guesses.

Globle uses a similar approach, asking you to guess a particular country every day. Unlike Worldle, however, Globle colorizes each guess on an interactive globe with four levels of closeness. The real problem with Globle is that it doesn’t auto-complete country names (although suggestions from the iOS keyboard can help). Good luck spelling Kyrgyzstan on your first try. You can guess as many times as necessary, though that may just prolong the agony of ignorance.

A friend likes Worldle because it helps her improve her geographical knowledge, but I find both games frustrating, particularly when the place in question is an island. Can you tell the difference between Tuvalu and the Faroe Islands?

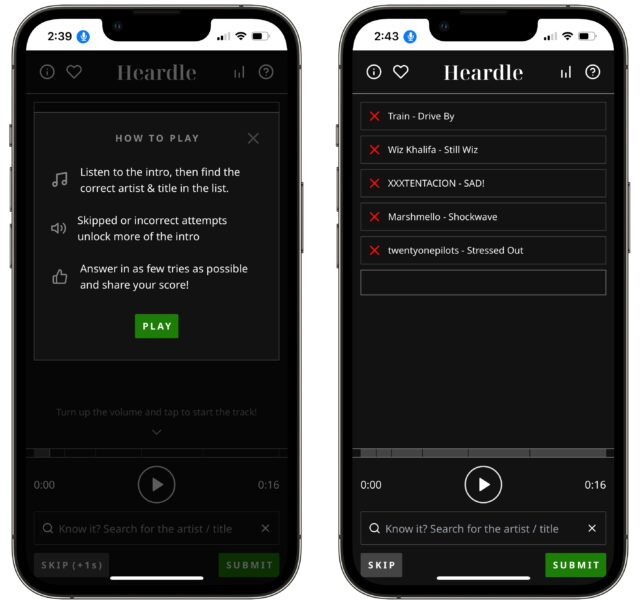

Heardle

Don’t even think about playing Heardle unless you’re under the age of 30 and stream popular music regularly. Heardle takes its cue from the Name That Tune game show that premiered on radio in 1952, moved to television in 1953, and has since been revived more times than a Marvel superhero. It plays bits from the intros to songs that are among “the most streamed songs in the past decade” and challenges you to, well, name that tune in six guesses. At least it gives you suggestions as you type. When I fail, and I’ve failed completely every time I’ve played, I discover that not only do I not know the song in question, I’ve never even heard of the artist. It might be fun if I could limit it to music from the 1970s and 1980s, but otherwise, I want Heardle off my lawn.

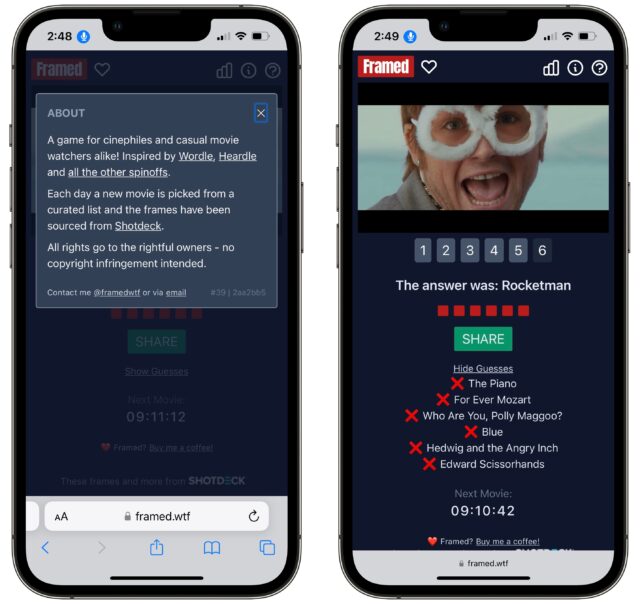

Framed

Are movies more your thing? I mean, really your thing? You might stand a chance with Framed, which uses the traditional six guesses approach with individual frames from a movie. In essence, it’s Name That Film. I’m not a movie buff, so my every try at solving Framed has ended in ignominy. I know the names of many movies that I haven’t seen, but I have no idea what they look like, and Framed doesn’t give clues, just more frames from the movie.

Other Wordle-Inspired Games

During my research, I ran across even more Wordle-inspired guessing games. Some that I found utterly bewildering included:

- Adverswordle, which has something to do with making the bot guess

- Box Office Game, in which you try to name the five top-grossing movies from a random week

- Cloudle, which asks you to guess the next five days’ weather forecast for a random city

- Crosswordle, which runs Wordle in reverse, forcing you to identify guesses that lead to the provided answer

- Dungleon, which replaces letters with fantasy character pieces and has secret rules

- Murdle, which combines Wordle with Hangman

- Passwordle, in which you see why password cracking is done by computers

- Squirdle, which has you attempt to guess at Pokémon characters

- Who Are Ya?, which challenges you to guess football (soccer) players

As I was nearing what I thought was the end of this article, I stumbled upon Wordles of the World, a site that attempts to be comprehensive with its list of (so far) 762 Wordle-like games and resources in 149 languages. I think I need to go lie down now. And maybe play a simple game of Wordle.

Understand Cryptocurrency, but Don’t Invest in It

Cryptocurrency is on everyone’s lips, but it should be in no one’s virtual pockets. An overhyped form of imaginary value storage, it has all the disadvantages of cash, suffers from all the volatility of an overhyped penny stock, and consumes more power than a mid-sized European nation. Although it has been vaunted as untraceable, anonymous, and beyond the reach of governments, none of that is true. Law enforcement agencies have used cryptocurrency to take down crime rings, stop people from exchanging child sexual abuse material, and seize massive amounts of Bitcoin and other currencies.

At one point, I thought cryptocurrency might be among the most exciting and important innovations in technology and finance. It felt as though it had a transformative power in transcending national boundaries, providing a measure of personal independence outside of that offered even in democratically run countries, and disconnecting value and ownership from greedy, predatory, and sometimes corrupt financial institutions.

Over several years, my thinking has evolved to a provisionally cynical position. As I’ll discuss, none of the promises and benefits of cryptocurrency have materialized. Instead, the field has devolved into hype and scams, with the most avid participants—whether fraudsters or true believers—just trying to get as many people as possible to pump real money into digital currency. The phrase “digital Ponzi scheme” crops up a lot.

My overriding advice right now is, “Don’t buy cryptocurrency.” No existing cryptocurrency systems provide investing, hedging, or other financial benefits worth engaging with compared to existing financial instruments and markets.

But I say I’m “provisionally cynical” because, despite all that is wrong with the current systems, I urge you to learn as much as you can about cryptocurrency’s underlying principles. Some portion of what we see today will migrate into mainstream finance. That will include activities as broad as sending money to a friend, making certain retail and online purchases, investing in stocks, raising money for projects, and even buying a house. All of these could be wrapped up in immutable, verifiable transaction records.

It might seem contradictory to say you should avoid engaging in cryptocurrency while becoming a student of it. But that could apply to any dangerous or risky endeavor you want to learn more about safely.

Within a few years, more than one government will issue an official form of cryptocurrency, likely including the United States; China is already underway with a digital renminbi. In addition to financial records currently managed by government entities like county clerks, permanent ledgers will appear that record details of sales, purchases, and other exchanges of value that require an auditable record.

Private companies, non-profit organizations, and government bodies will likely create ways to participate in decision-making by establishing a cryptographically verifiable stake of value that also gives you voting rights or other involvement in governance. This is akin to stock ownership but with fewer intermediaries preventing you from exercising your opinion.

None of the above is techno-futurism or hype. It all exists today in some form, albeit in examples that are often shaky, unreliable, mismanaged, fraudulent, or intended for Big Brother-like oversight. Bitcoin may eventually fade away—much like once-popular technologies like Gopher and FTP did—but cryptocurrency will survive. A massive percentage of today’s transactions already occur electronically but in such a haphazard and unverifiable way that we need something better.

We’re migrating to a situation where people need to differentiate between public, speculative projects that are far too risky—or simply corrupt from the start—and valid projects based on low-carbon, reasonably scalable private and governmental blockchains used for discrete purposes.

(I learned a lot of the nitty-gritty about cryptocurrency when researching and revising my book, Take Control of Cryptocurrency, which delves into cryptocurrency topics at greater length.)

Understanding Cryptocurrency Basics

I constantly wrestle with how to explain cryptocurrency to the uninitiated because it involves aspects that cross the boundaries of other kinds of financial instruments, like cash, debit cards, and stocks, as well as those that have no analog in everyday life.

Here’s a gloss on how cryptocurrency is like—and unlike—things we all know:

- Paper currency: Each cryptocurrency unit is uniquely numbered like paper money. It can pass between hands without help from a financial institution. The unit value is denominated as part of its nature. Transactions are quasi-anonymous: it’s hard, but not impossible, to trace the flow of value from one party to the next, at least for law enforcement when large amounts are involved. But cryptocurrency isn’t like paper money because you have to pass it through an online system. Plus, some cryptocurrencies, like Bitcoin, are highly volatile, unlike cash in most modern societies.

- Debit-card transaction: When you use a cryptocurrency, you’re always sending money; there’s no invoice, billing, or debiting process. This makes it somewhat like using a debit card—an electronic transaction that comes out of your stored value (your savings) held on a ledger somewhere (your bank’s records) that’s sent in a way the recipient can verify as legitimate. Yet, cryptocurrency’s “ledger” isn’t stored in a central location like a bank—it’s a distributed consensus that agrees on what transactions have occurred, so there’s no one to complain to if something goes wrong.

- Stock ownership: In many ways, cryptocurrencies are like stocks. Owning shares in a company lets you ride the tide of a combination of the firm’s real value and sentiment about its future earnings. For a company in turbulent times or around which rumors swirl, the price of shares can zigzag up and down. The stock can be exchanged for currency through intermediaries and vice versa. Cryptocurrency shares the volatility of stocks but doesn’t reflect any underlying fundamentals, just market perception. And unlike stock, no “company” exists whose value and performance are reflected in the “shares.”

- A password: At its heart, cryptocurrency relies on knowing secrets. Proving ownership or spending any chunk of crypto coin requires an encryption key that only you possess. But unlike a password used to unlock a computer or online account, you don’t gain access to anything with the key—you only use it for proof. All your ownership comes from that proof.

So with that in mind, what is cryptocurrency itself? Although it might take some advanced study to truly understand it, I can explain the basics in a few sentences. Cryptocurrency is a financial instrument that uses cryptography instead of other methods (like physical possession or traditional financial institution database entries) to verify ownership. When you purchase cryptocurrency, the transaction is written into a permanent, distributed ledger—a blockchain—that uses cryptographic algorithms to render the records permanent, unchangeable, public, and verifiable by any party.

As fully decentralized systems, cryptocurrencies don’t need a government or other single entity to issue units. Instead, cryptocurrencies rely on a consensus mechanism that lets participants bypass trusting any individual or organization. The blockchain contains the “truth”—you de facto don’t own that cryptocurrency if your record of ownership isn’t in the ledger, if you can’t produce a private encryption key related to your ownership (the classic “lost key” scenario), or if the transaction can’t be verified. It’s like having a bank account with a balance you can’t access—ever. Because there’s no central authority managing a cryptocurrency, there’s no one to complain to in the way you might dispute a charge with your credit card company or force a bank to release your savings account through a court action.

How Bitcoin Works

Here are the four major parts of Bitcoin, the highest valued cryptocurrency by far:

- A group of people (miners) voluntarily compete over short periods of time, about ten minutes, to solve a mathematical needle-in-the-haystack puzzle. The miner who solves the puzzle first is the winner and receives a chunk of Bitcoin. Only one miner is successful for each block; all other effort is discarded. The puzzle resets, and the contest begins again. Most mining is done by a handful of heavily invested mining companies.

- A network of peer-to-peer, independently operated software servers (nodes) exchange information about transactions waiting to be recorded, recently solved puzzles, and the state of the network and system.

- Sets of transactions are tied together cryptographically through mining (blocks). A miner creates a block when they solve a mining puzzle and broadcast their solution to nodes.

- An immutable ledger of all completed transactions (blockchain) grows by one block of new entries each time the mining puzzle is solved and accepted by nodes.

One way to understand how Bitcoin works in practice is to compare a Bitcoin payment with a purchase made using a chip-based card or mobile payment system like Apple Pay. Here’s how that card-based transaction proceeds:

- When prompted to pay (either in person or via mobile payment in a browser or app), your card or mobile device performs a cryptographic handshake across a network to validate the payment and create a unique set of information that the payment network accepts. Your possession of the card (in person) or a biometric approval (like Face ID) makes the transaction legitimate.

- The merchant receives a digital acknowledgment that a payment was made.

- In a ledger maintained by the payment system, the transaction amount is debited from your record. Either it’s applied as a charge on a credit card ledger maintained by your credit card issuer, or it’s debited against your bank account and transferred as an electronic record through the payment network as a credit on the seller’s merchant account.

- Fees are collected in various ways across the system, typically from the merchant, and paid out in various amounts to the payment processor, payment network (like Visa or Discover), and merchant’s bank.

- If your payment is later declined, the merchant can complain to the payment network. If you have a problem with your purchase, you may be able to have the charge or debit reversed and refunded to you through your bank or credit card issuer.

With a Bitcoin payment, the process works similarly in total, but the actual set of actions is quite different:

- Get someone’s Bitcoin address. (Even ordinary people may have many.) It may be provided in several ways, including plain text or a QR code.

- Send them money via wallet software. The transaction requires a fee to encourage miners to consider including your transaction as part of their puzzle block. The wallet software essentially stores the encryption secrets you need to create a properly formatted transaction that proves your ownership and uploads that transaction to a node.

- The node broadcasts your transaction to other nodes in the network. Since it’s a peer-to-peer network, nodes are constantly receiving and broadcasting transactions.

- The transaction floats in a pool of all outstanding transactions until various miners’ software decides the fee justifies including your transaction in their attempts to solve the puzzle.

- A miner whose transaction payload includes your transaction solves the puzzle and distributes a block with the transaction baked in.

- Other nodes independently validate that block and add it to their copy of the blockchain.

- The recipient can validate that the transaction has been added to the blockchain by examining recent entries on the blockchain. Wallet software automates this.

New units of Bitcoin can be created only by miners, and only a limited amount of Bitcoin can ever be created. That amount left halves about every four years. The current reward is 6.25 Bitcoin per block. You can divide Bitcoin units down to tiny units called Satoshis, which are one-hundred-billionth of a Bitcoin. For example, $5 is roughly equivalent to 0.000124 Bitcoin or 12453.05 Satoshis.

Miners can then use those Bitcoin units to pay others in Bitcoin or cash out through cryptocurrency exchanges. These exchanges provide crucial liquidity for Bitcoin markets. Without parties willing to trade Bitcoin for other cryptocurrencies and government currency, Bitcoin would be an entirely closed system. Exchanges bear the risk of holding and trading cryptocurrency. They have to determine what price they will pay or charge for Bitcoin based on their own algorithms and monitoring prices paid at other exchanges. Cryptocurrency exchanges are similar to international currency exchanges, earning a fee as part of these conversions. When many people want to buy Bitcoin, the price may climb rapidly, but there’s a lot of Bitcoin to sell. Conversely, when people want dollars for Bitcoin, the price can plummet as exchanges hold relatively limited amounts of hard currency compared to conventional banks or central government banks.

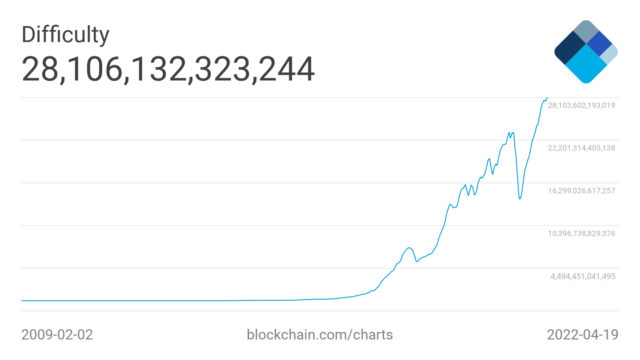

The Bitcoin algorithm provides a mechanism to keep block production on a cadence of about one every 10 minutes. That rate prevents the peer-to-peer network from being overwhelmed while also providing time for transactions to “cure”—to be in the blockchain long enough to be securely locked in place. (This helps protect against the 51% attack described below under immutability.) As miners add computational capacity, the Bitcoin system resets the difficulty of the puzzles they have to solve every few days. The additional computational speed is effectively offset by the difficulty factor, resetting it back to the 10-minute cadence. This method of requiring some weighted amount of effort is called proof-of-work, and it’s the basis of trust as it can’t be faked. Only hard work can solve the puzzle—there’s no shortcut.

Constantly adjusted difficulty requires miners to invest in faster equipment lest their competitors begin to earn more rewards. This strategy burns more and more power in a Red Queen’s race to get almost nowhere: the outcome is the same, but the electrical consumption and environmental cost increase in step with the difficulty. Mining makes economic sense only as long as the miners’ cost of equipment, facilities, and power remains, on average, lower than the value of the Bitcoin they earn as rewards.

Occasionally a blip occurs—such as a sudden drop in Bitcoin’s price or Chinese authorities banning mining—that reduces the profitability and takes mining capacity offline. In those cases, the difficulty resets to a lower level. But the strong trend is for the difficulty to increase over time.

Ethereum and NFTs

Bitcoin’s younger sibling is Ethereum (its currency is Ether). One Ether is worth about 8% of a single Bitcoin, and cryptocurrency exchanges value the full market value of the outstanding Ether at about half that of Bitcoin. Unlike Bitcoin, Ethereum wasn’t created as a replacement for cash, nor does it have a limit on the maximum amount of Ether that can be mined. The Ethereum network can perform simple transfers of value, and that’s its most frequent use.

But its power lies in smart contracts, network-based programs that run when they receive an input. They’re like tiny virtual software containers. Smart contracts can allow complicated rules for taking an incoming payment and splitting it up, but they can also be used for more sophisticated purposes. That includes decentralized autonomous organizations (DAOs), groups that set up smart contracts that define ownership, voting, and the consequences of votes—a nice idea, but such groups exist largely outside existing regulatory structures. That can cause problems when they fall afoul of fraud, attacks, and mismanagement. Ethereum also supports distributed apps (dApps), which remain in an experimental stage: they allow the use of the Ethereum network as a general-purpose distributed computer.

Ethereum also enabled one more element you should know about because they have been so omnipresent in the media: NFTs, or non-fungible tokens. NFTs are also entries on a blockchain but are formatted in a special manner that allows them to be created without an associated currency-style value. An NFT is effectively a serialized token with its uniqueness established by residing on the blockchain—like a signed baseball card or a ticket to a concert.

To explain, a fungible asset is one that’s identical to all others of its class: any dollar in one bank account is the same as any dollar in another. In contrast, a non-fungible item can’t be exchanged like for like. In the real world, non-fungible items include original works of art, real estate, and unique collectibles.

An NFT doesn’t confer ownership of an underlying asset, like a copyright, licensing permission, or possession of a physical object. It’s just a pointer that points to a URL. Once set, that URL can never be changed because NFTs are immutable. This is why people joke about “right-clicking to steal” NFTs: most NFTs point to images hosted on publicly available Web pages that can be downloaded locally by right-clicking and choosing Save Image As.

Bitcoin can’t host NFTs because it’s not “programmable,” so many NFTs are based on Ethereum. However, there are also now cryptocurrencies created solely to issue NFTs. As tokens, NFTs can be sold for arbitrary values. They aren’t fixed, like units of cryptocurrency.

The most reported-on use of NFTs is making iterative pictures of ugly graphics, like apes and lions. That’s the least interesting use, however, as NFTs could provide both verifiable uniqueness for all sorts of things and transferable ownership.

With those basics out of the way, let’s look at the myths of cryptocurrency and then see where it’s headed.

The Myths of Cryptocurrency

People who are cryptocurrency advocates or promoters tend to gloss over or ignore its drawbacks. You can hear them and more credulous tech writers recite a litany of cryptocurrency benefits:

- It’s anonymous.

- It’s untraceable.

- It’s decentralized.

- It’s immutable.

- Immutability is good.

- It’s anti-inflationary.

- It always appreciates in value.

- Transactions are cheaper than credit cards.

- It’s removed from governmental control.

- The environmental problems will be solved.

- It’s safe.

- It’s simple.

I could write even more thousands of words explaining why all of those are misguided, false, exaggerations, or require footnotes and provisos. Let’s see if I can instead knock them off in a few paragraphs.

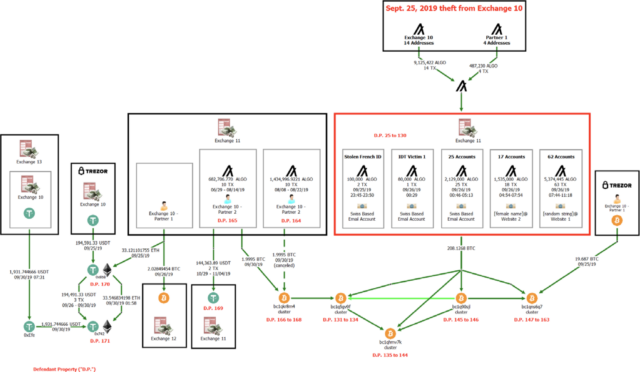

It’s anonymous. It’s untraceable. Cryptocurrency transactions rely on a public blockchain that everyone can see and validate independently. This is part of the basis of decentralized trust: you don’t have to believe anyone; just check the cryptographically consistent record. As a result, you can trace transactions over time as they move between addresses. Companies like Chainalysis specialize in this. It’s better to say that Bitcoin and other major cryptocurrencies are pseudonymous: identity and address are separate things but can be associated. (A few cryptocurrencies, like Monero, offer something much closer to irreversible anonymity, but their transactions are a tiny fraction of all those conducted.)

It’s immutable. It’s decentralized. The blockchain is designed to be immutable, but that relies on true decentralization of mining. Any time at least 51% of the computational power across the entire mining network is controlled by a single entity or back-room deal, the chain could be reversed by a few too many blocks depending on the amount of computation. It could allow double-spending, in which units of cryptocurrency appear in a block that becomes invalid but which the receiving party has already acted on (like releasing a real-world escrow or transferring ownership of a digital asset). Such a cabal could even prevent others from having their transactions written to the blockchain. This isn’t theoretical; it has happened several times.

Many cryptocurrencies and seemingly nearly all NFT projects have a high degree of central ownership: one or a few parties control the entire system and the direction it takes. Even when a larger group of people are involved, a small minority that controls the majority can have effective control. For instance, following a huge DAO meltdown in 2016 that would have cost participants the equivalent of $150 million, the core Ethereum group, the Ethereum Foundation, stepped in to rewrite Ethereum’s rules to annul the theft. This resulted in a hard fork of Ethereum, resulting in the Ethereum Classic spin-off created by miners who disagreed with the move. Even with wallets, software that manages ownership and sales, consolidation among vendors can lead to a situation where an immutable entry simply doesn’t appear because the wallet developer blocks it.

Immutability is good. You could argue that, in general cases, blockchains are immutable. But is that always good? Immutability is overrated in one sense. When you make a credit card purchase, you have a variety of protections under the rules of the card, the card’s issuing bank, and your state or regional or national government. Credit card transactions aren’t immutable, and thus they can be reversed to respond to fraud, misrepresentation, or other reasons. (Banks may hold balances or require reserves to cover reversed transactions.) Cryptocurrency transactions would largely sidestep such protections.

Also, blockchains can store or point to all sorts of data. Future blockchains may have the spare capacity to encode large amounts of data, such as complete legal contracts, media, and software source code. So what happens when CSAM, “revenge porn,” deeply personal details, and stolen software are permanently encoded into blockchains? For some categories of harm, the blockchain might be effectively illegal to possess on your computer or even view parts of—it simply hasn’t been adjudicated.

It’s anti-inflationary. It always appreciates in value. At one point, economic/political promoters of cryptocurrency liked to assert that Bitcoin and others would resist inflation. As inflation rises, currencies devalue relative to what they can purchase. Cryptocurrencies were supposed to counter that by having a rising exchange rate with real-world currencies to offset devaluation. It was a tricky point to make in the middle of one of the lowest periods of inflation across established economies in global economic history. And it hasn’t happened as inflation has increased in the last year. Instead, cryptocurrency has generally been so volatile, with huge spikes and drops multiple times since 2019, that it’s hard to draw any conclusion.

Internally, Bitcoin and Ethereum try to restrict the growth of their basic units. Bitcoin was created with a finite number of coins; Ethereum is unlimited but implemented a change in August 2021 to “burn” (permanently destroy the value of) Ether with every transaction relative to its complexity to prevent the deflationary effect of constant growth of Ether.

Transactions are cheaper than credit cards. A selling point of Bitcoin in its earlier days was that it would cost fractional US cents to carry out a transaction compared to the roughly 3% that credit cards eat up. It would enable micro-transactions, letting you send pennies to pay bloggers and dollars to pay musicians. That didn’t last.

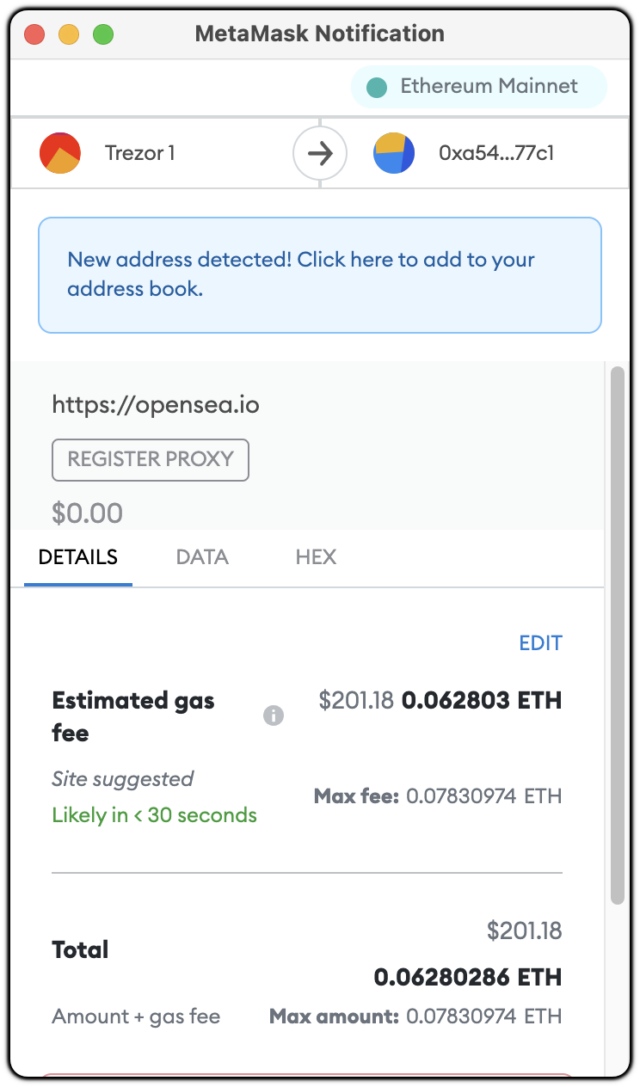

Because Bitcoin and Ethereum can handle only a modest number of transactions per minute, the fee paid to miners becomes a huge component of having transactions written to the blockchain. This pressure caused the cost of Ethereum transactions to rise to tens of dollars in 2021, regardless of the size of the transaction. Bitcoin fees have remained lower but can still average several dollars. (Some attempts to increase the transactions-per-second rate involve layering other blockchains on top of existing cryptocurrencies. However, building a robust infrastructure on top of unstable foundations comes with many risks.)

On top of that, Ethereum has gas fees that are tied to the cost of executing a transaction, since all Ethereum transactions equate to programs that consume computational resources. Complicated smart contracts can require huge amounts of gas compared to a simple value transfer. These gas fees can become astronomical—much higher than the actual amount being transferred. Plus, you can’t accurately predict how much gas a transaction will require. If your wallet transmits the transaction without enough gas, you forfeit the gas fee and your transaction isn’t added to a block. The worst of both worlds! (The workaround is to send too much gas, after which the extra is refunded along with the output of a transaction. Previously, gas used to be paid to miners but has been burned since August 2021, as noted above.

This has resulted in an absurd situation where refunds from a failed collaborative project to buy a copy of the Declaration of Independence cost participants more than their initial contribution. Such scenarios are common.

The environmental problems will be solved. Cryptocurrency remains an environmental disaster of the highest order. Bitcoin burns electricity equivalent to the requirements of a modest-sized European country to no good end: the value per Bitcoin doesn’t match the amount of energy required to mine it. Mining a single Bitcoin could require 1 watt or 1 gigawatt of power. For practical purposes, the cost of mining produces an effective ceiling due to capital costs, operating expenses, and power usage. Miners try to stay in the black by mining more Bitcoin than their costs. However, if Bitcoin skyrocketed to ten times its current purchasing power, miners would fight an upward race to find more power wherever they could. The credit card network is millions of times more efficient per transaction and scales incrementally instead of in lockstep as transactions increase—ten times the current volume doesn’t require ten times the current hardware or electrical use, as most of the investment is in basic infrastructure.

Because the vast majority of cryptocurrencies, led by Bitcoin and Ethereum, use algorithms that require particular computations, it’s possible to estimate how many operations are performed per second across the network. Digiconomist uses that and other data to estimate a range of about 80 to 320 terawatt-hours per year of use between Bitcoin and Ethereum. That’s somewhere between the amounts of electricity used by Belgium and the UK.

Miners also literally burn through hardware, resulting in shortages of chips used for more productive purposes and a massive flow of e-waste, most unrecyclable. Digiconomist estimates Bitcoin mining currently results in 34 kilotons (70 million pounds) of tossed gear per year, equivalent to the IT waste of the Netherlands.

Promoters regularly try to explain how cryptocurrency is en route to becoming “greener” in two ways. First, Ethereum may be nearing the end of a multi-year transition to Ethereum 2.0, an energy-efficient algorithm that scales well without a corresponding leap in resources. The new protocol relies on proof-of-stake, which validates new transactions based on people’s ownership of Ether rather than how much computational work they perform.

If Ethereum 2.0 is successful, about which there are grave doubts and major anxieties, it could reduce Ethereum’s energy consumption by 99% or more. Still, even at 100 times more efficient, it remains several orders of magnitude worse than, say, a Visa card charge. Promised years ago, the transition is always just a few months away. In fact, just days ago, the latest upcoming target for the transition was pushed to… a few months away.

Many crypto advocates argue that the mining world has a plan—already alleged to be somewhat underway—to transition to renewable resources, such that it will ultimately be emissions neutral. Instead of effectively mining Bitcoin from coal and natural gas, why not tap into solar and wind, or put a geothermal generator on a volcano? These are nice ideas, but the Earth is a closed system: there is no surplus renewable power generation equipment or naturally occurring, accessible sources of renewable energy. Skeptics call this greenwashing, in which noble reductions are trumpeted while the reality is much different.

Because only a finite amount of equipment can be made and put into service, any “non-productive use” (burning computation cycles for cryptocurrency) removes capacity from other purposes. Either miners buy a lot of solar and other equipment or output of renewable plants, just as they caused hardware shortages for GPUs and SSDs, forcing other generators to use dirtier power, or they keep using the dirtiest power as the rest of the world moves towards a less destructive approach.

It’s removed from governmental control. Earlier in this story, I noted how governments have become adept at tracing cryptocurrency and, more recently, at reclaiming it. The US Department of Justice seized $3.6 billion (8 February 2022 valuation) of Bitcoin connected to a major 2016 hack of the Bitfinex exchange. That’s the largest such seizure, but dozens of others have occurred, including $34 million from an alleged scammer in Florida by the U.S. government on 4 April, $25 million by the German government on 5 April, and an unclear amount of donations to those involved in occupying downtown Ottawa earlier this year. (Josh Centers wrote an elaborate analysis of crypto as a workaround to governments for his prepping-related publication, Unprepared.)

It’s safe. Advocates would like to tell you that it’s safe to invest in and possess cryptocurrency, but to rebut that point, I simply suggest you read through Molly White’s “Web3 is going just great” site, which is a seemingly endless feed of scams, rug pulls, hot potatoes, phishers, incompetents, and other old-timey frauds and business failures rendered anew. (Rug pulling is raising funds for a project and then taking those funds without delivering on the promises in fairly quick order. A hot potato is a coinage I may have come up with for finding the least savvy person to leave holding the bag—one without any money in it.)

It’s simple. If you’ve read this far, you’ll understand why this claim should elicit hysterical laughter.

Where Cryptocurrency Is Headed

How can I argue cryptocurrency is part of the future of financial systems when I’ve just told you how thoroughly pointless, broken, and fraud-ridden it is? Because it has a number of excellent ideas that could be expressed in more reliable, trustworthy, and useful ways. To achieve these goals, we need new cryptocurrencies that change some of the principles proven false in the idealized initial approaches.

- First, some elements of centralization could dramatically improve cryptographic-based transactions without putting any or all of it in the hands of governments, all while keeping identity secret without exaggerations about anonymity or privacy. Instead of trusting software developers and cryptocurrency creators—while claiming to trust no one—we would trust other entities that can be better vetted. The notion of complete decentralization was clearly a dream of idealists that, in practice, has proven as problematic as the worst cynics predicted: the control of most cryptocurrencies is in the hands of a few people who have accumulated lots of money. Ditto, anonymity, as I’ve noted throughout this article.

- Second, any new cryptocurrencies need to provide a way to cap and control transaction fees to keep them predictable and low, a claimed advantage that hasn’t proved to be the case in reality. Imagine a value-transfer system that was far cheaper than the credit card system, which averages around 3% in the US, and other more costly person-to-person and funds-transfer systems. Later cryptocurrency systems that learned from Bitcoin and Ethereum can carry far larger numbers of transactions, reducing pressure and enabling far cheaper transactions.

- Third, a key goal should be reducing fraud. Existing cryptocurrencies regularly suffer from exploitable weaknesses across the ecosystem—some fundamental in the protocols, some in wallet software, some in smart contracts, and some at consumer crypto-financial websites. For instance, as Cory Doctorow noted of smart contracts, they “don’t just create instability by being too complex to understand and vulnerable to coding errors–they’re also fraud magnets”; being immutable, they can’t be updated and require you to run a buggy program forever. The credit card system isn’t a paragon to compare to: it lost nearly $30 billion to fraud in 2020, a number expected to rise. Because a tightly controlled secret is at the heart of all cryptocurrencies, the possibility of reducing fraud and theft has a high upside for consumers, banks, and businesses.

- Fourth, a government-regulated cryptocurrency could make trans-border commerce easier without reducing accountability, fraud resistance, and protections against funding terrorism, laundering money, and engaging in financial crime. It’s typically slow and costly to send money between countries (outside of the European Union), particularly for smaller amounts. Economic migrants and cross-border workers may pay roughly 5% to 8% of what they send back to family in remittance fees, for instance, for over half a trillion dollars of transfers.

- Fifth, a future cryptocurrency could allow an organizational structure in which your stake gives you proportional voting rights in projects that aren’t publicly traded corporations. (Companies tend to have concentrated ownership and even separate classes of voting shares that dilute the effect of individual and small owners.) We can see this in effect already with decentralized autonomous organizations that use smart contracts that combine a purchase with a stake. A DAO ostensibly provides validated voting, a public record, and directly enforceable outcomes. The reality hasn’t matched up with the theory yet, but there might be a role for smart contracts in certain kinds of organizations.

One of the earliest examples of a more regulated, non-volatile, and perhaps government-backed cryptocurrency will likely be a stablecoin. A stablecoin is a cryptocurrency pegged to a fiat currency, like the dollar or euro. Existing stablecoins, like Tether’s USD, rely on managers who buy and sell assets to maintain holdings they claim are redeemable on a 1:1 basis between USD and actual US dollars. (Tether’s claims of reserve assets are highly disputed due to the company having over $80 billion in ostensible outstanding stablecoins; various parties have claimed that Tether can possess only a fraction of that in cash and short-term liquid securities.)

Current stablecoins don’t have their own blockchain but are built as special kinds of transactions on top of existing cryptocurrency blockchains, making them no better at avoiding underlying issues like environmental devastation and processing speed. Management is centralized at the top layer, as the stablecoin operator has to maintain assets and issue new stablecoin. However, once issued, stablecoin units can be as freely traded without central involvement as any other cryptocurrency.

Governments like the United States already use their own non-cryptographic ledgers to track electronic cash. The U.S. Federal Reserve said that for February 2022, out of $21.8 trillion in cash in the money supply, only about $2.2 trillion—roughly 10%—circulates as notes and coins.

What’s the difference between a US-managed stablecoin and the Federal Reserve’s record of cash? Cryptographic validity and transaction tracing. For some people, the former is highly desirable and the latter something they want to avoid out of principle; for governments, both could be useful. Transaction tracing is a key reason China is pushing forward with its digital renminbi.

A private or invitation-only blockchain could power a US Treasury stablecoin. Private blockchains in which stakeholders maintain trust internally have become increasingly popular. Given that the US government has never defaulted, it might be able to create and run a private blockchain to power a US Treasury stablecoin. You could also imagine a consortium of US credit unions given a charter to run a stablecoin to further their mission of extending banking, reducing fees, and providing fair mortgage and lending rates.

That stablecoin might not become available for years for ordinary people or uses. Instead, it might be a way to transfer value securely among institutions for their own purposes or for consumer and business needs. For instance, imagine buying a house. Instead of escrow, a stablecoin transaction would provide the security that money has changed hands with cryptographic assurance instead of a call or letter from a bank. (Or, for those who remember, a certified check in an obscenely large sum.)

Countries would need to update their laws to deal with the widespread use of cryptocurrency. For starters, laws need to change to deal with immutability when so much else about property can be adjudicated: a court might say money has to go from one place to another and enforce that through the banking system, but it would have no power over existing cryptocurrencies.

Yet, every time I need to send money to another person, pay for something online, or receive payment for goods I sell, it’s hard not to imagine that our creaky old financial system would benefit from a modern approach that uses encryption as a component of security and assurance.

It’s hard to say what the future of cryptocurrency will look like. In the meantime, I repeat my advice at the outset: watch and learn, but don’t invest.

If the above intrigued you, you can read much more about nearly every aspect of it in my book, Take Control of Cryptocurrency.