#1616: Explaining passkeys, Apple challenges for senior citizens, macOS 11.6.7 Big Sur fixes email attachment bug

In its WWDC keynote, Apple introduced a new authentication technology called “passkeys” as a simpler, more secure replacement for passwords. Glenn Fleishman joins us to explain how passkeys work and why they’re so much better than passwords. Adam Engst draws on a recent experience helping elderly friends with their Macs to offer feedback on how Apple can create a better experience for senior citizens. Spoiler alert: passkeys are a step in the right direction. Adam also shines a light on Apple’s quiet update to macOS 11.6.7 Big Sur, which fixes a bug that made email attachments difficult to open. Notable Mac app releases this week include Pages 12.1, Numbers 12.1, and Keynote 12.1, Ulysses 27, Acorn 7.2, Zoom 5.11, SoundSource 5.5.3, EagleFiler 1.9.8, DEVONthink 3.8.4, GraphicConverter 11.6.2, SpamSieve 2.9.49, and Quicken 6.8.

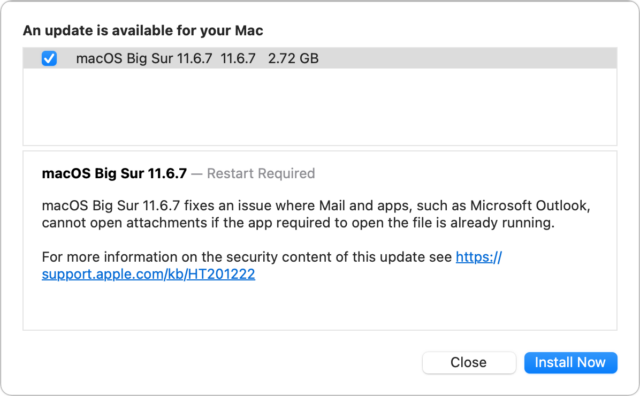

macOS 11.6.7 Big Sur Fixes Email Attachment Bug

I’m a little late to this party because all my main Macs are running macOS 12 Monterey, but about two weeks ago, Apple quietly released macOS 11.6.7 Big Sur separately from other updates. The release notes are the first since macOS 11.5 that provide any useful detail, noting that the update fixes a problem in macOS 11.6.6 with opening email attachments if the app required to open the file was already active. Users received error messages claiming they didn’t have the necessary permissions.

TidBITS Talk user chs had trouble printing after updating to macOS 11.6.7 on an M1 MacBook Air; it seems that their installation of Rosetta was removed as part of the update such that they had to reinstall it to enable the Brother printer driver (although an update to the native Brother software might also have resolved the issue). Will M also noted that, after updating to 11.6.7, Time Machine completed the first backup to his Time Capsule since he had installed 11.6.5 in April.

In short, for those still using Big Sur, it’s worth updating to macOS 11.6.7 using Software Update to address the email attachment bug and potential Time Machine blockages, but beware that you might need to reinstall Rosetta. Or just make the jump to Monterey.

Helping Senior Citizens Reveals Past Apple Lapses and Recent Improvements

Over the last few weeks, I’ve spent some time helping my late friend Oliver’s elderly father JP and his wife Gretel, who are preparing for a move to an assisted-living apartment in another state (see “Oliver Habicht Dies of Pancreatic Cancer at 53,” 26 September 2020). They’re internationally renowned scientists in nutritional epidemiology and nutritional anthropology, and while they’re both suffering the seemingly inevitable physical ravages of age, they remain fully mentally competent, if occasionally slowed by medications and fatigue.

I had promised Oliver that I’d stand in for him as necessary, and since he had been JP and Gretel’s primary tech support person for years, I was happy to help when they said they had some computer questions. I knew what I was getting into, more or less, since JP was one of my first consulting clients in 1987 when I was a junior at Cornell and he lived just a block away. I’d go over, decipher the notes he left himself by naming empty folders on his Mac Plus, and help him work through various software and hardware problems.

We had time for only a few visits before they were slated to leave, and their house was being packed up around us, so they had three areas to focus on: dealing with old hardware, rationalizing their backup strategy, and coming up with a better password management system. In each case, I was struck by the fact that Apple has put some effort into addressing these problems recently, but in ways that won’t necessarily help older Mac users who aren’t using the latest hardware, operating systems, and technologies.

I don’t want to make overgeneralizations about people in their 70s, 80s, and 90s, since we have many highly technical and capable TidBITS readers in those age ranges (not to mention our centenarian—see “George Jedenoff: A 101-Year-Old TidBITS Reader,” 17 June 2019 and “102-Year-Old George Jedenoff Publishes His Autobiography,” 26 August 2019). But from what I’ve observed among the mainstream public, it’s increasingly common for the elderly to rely heavily on computers, tablets, and smartphones but have trouble with the constant change in the tech world. It’s not that the systems are necessarily too hard (though some could improve); it’s that there is too much to learn and it changes too frequently. Plus, those who have been using technology for decades tend to have a lot of older hardware around, further complicating upgrade and compatibility questions.

It’s tempting to fall back on that old saw, “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it,” and sometimes that’s true. But in the tech world, staying put often isn’t feasible. Some apps really do break purely from age (like 32-bit apps in macOS 10.15 Catalina), some updates require new minimum hardware and operating systems, and compelling capabilities appear in new and revised apps. Some level of change is inevitable, but everything gets harder when that change has been delayed for years. Here’s what I encountered.

Old Hardware

On my first visit, JP and Gretel had a box of random tech bits—keyboards, mice, USB hubs, power supplies—labeled with my name on a sticky note. (Sticky notes were everywhere, in fact, since they’re excellent reminders, and JP has long fit the mold of the absent-minded professor.) They also had an old MacBook Air, Mac mini, iMac, Dell PC tower, and PC subnotebook, all of which were weighing on them. None were in use, but they’d been kept instead of recycled in part because it’s hard to decommission an old computer soon after getting a new one. You never know if you might need the old one for something, and regardless of whether the machine has value to anyone, it’s important to erase the internal drive before disposing of it.

It was my job to erase the drives and get rid of the machines. Given the age of these machines, that’s proving more difficult than I anticipated. The 2010 MacBook Air was easy: I booted into macOS Recovery, reformatted the SSD, and reinstalled macOS. We even have a friend who wants to adopt it. But while I was able to erase the iMac’s hard drive, it insisted on having my Apple ID to install 10.11 El Capitan, and the installation continually fails. Although the Mac mini seemingly boots, I haven’t yet been able to get it to drive a display, so I can’t see what’s on the screen or erase its drive. (Several folks have helpfully suggested Target Disk Mode, which I plan to employ when I return to the project.) I haven’t gotten to the PCs yet—they may end up being drilled and recycled.

My point here is that if preparing a computer for disposal is this involved for someone with my experience, knowledge, and hardware (and the strength and flexibility to move computers and screens around), it will be beyond many older people. That’s especially true because cleaning off a Mac to dispose of it isn’t something that anyone other than a consultant or IT admin will do frequently.

Happily, this is one of those situations where Apple is moving in the right direction. First, the company encourages users to trade in or recycle old hardware. Second, starting in macOS 12 Monterey, Apple has made it easier to prepare a Mac to be passed on, albeit in a rather hidden fashion.

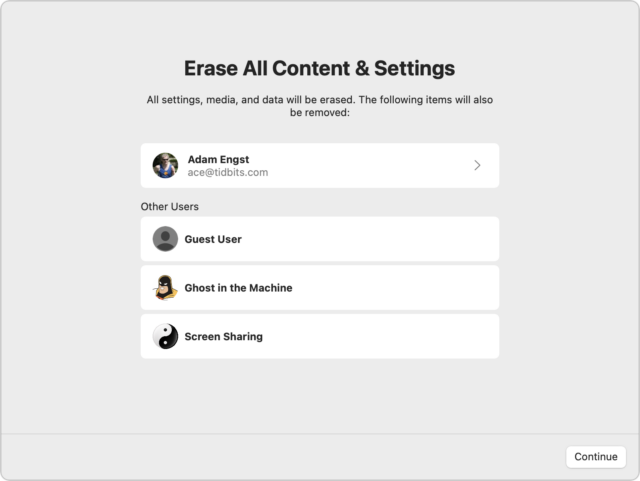

Here’s how you’ll prep a Mac for a new life if it’s running Monterey (this requires an M1 Mac or an Intel-based Mac with a T2 security chip). Open the System Preferences app, but instead of working inside its window, as you normally do, choose System Preferences > Erase All Content and Settings to start the Erase Assistant. After clicking Continue, it quits all your apps and proceeds with erasing all the data. Or at least I assume so since I didn’t let it erase my 27-inch iMac’s boot drive.

Alas, many older users may not have Macs that meet these requirements. For other Macs, hold Command-R at boot to start macOS Recovery, from which you can use Disk Utility to erase the boot volume and then reinstall a clean version of macOS.

Better Backups

As long-time Mac users with advice from Oliver, who was an IT professional, JP and Gretel both had Time Machine drives for local versioned backups and offsite backups to IDrive. They understood the importance of offsite backups but weren’t happy with IDrive and wanted a new Internet backup service. They were also laboring under two common confusions about backups:

- They wanted to know if they could store other files on their capacious Time Machine drive. Technically, that’s possible (see “How to Use Extra Space on an APFS Time Machine Drive,” 20 May 2022), but it’s a bad idea to mix backups and original data on the same physical drive, particularly for people who don’t have a crisp awareness of how to maintain multiple backup systems.

- Along with IDrive, they were paying for extra storage on Dropbox and Google Drive and wanted to know if they could back up to that storage. Again, it’s technically possible, but both provide online syncing and storage, not true backup. For backup with versioning and protection against file deletion, a backup app is necessary.

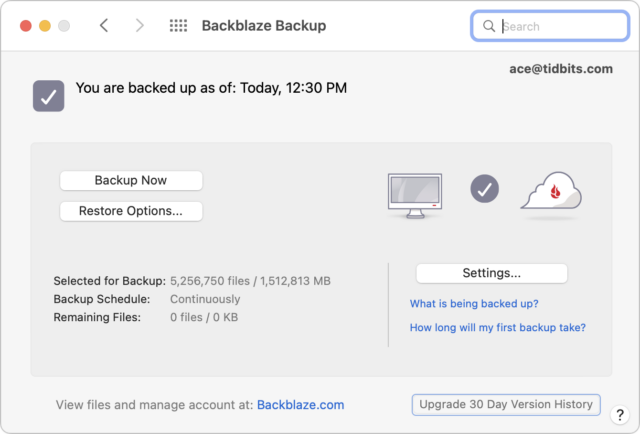

After talking it through, and taking into account that they were leaving the area shortly, I set them up with Backblaze for $70 per computer per year and helped them turn off auto-renewal on the IDrive account. They also dropped their Dropbox accounts to the free level, but stuck with the lowest level Google One storage plan to ensure enough space in Gmail.

Backblaze is a good system, particularly in the set-and-forget category, which is essential for elderly folks who don’t need to spend more time managing their backups. The main problem JP and Gretel had initially was the disconnect between the Backblaze preference pane on the Mac and its Web-based interface for additional management and file restoring. They also fell prey to the watched-pot problem of the first backup, which took a few days to complete.

Apple has addressed the need for backups for iOS and iPadOS with iCloud Backup, but I remain surprised that the company hasn’t released an iCloud Time Machine that would back up Macs to paid iCloud+ storage (see “Five Enhancements for Future Apple Operating Systems,” 19 May 2022). Such a built-in system would encourage more Mac users—regardless of age—to protect their data since they wouldn’t need to buy an external drive, and it could serve as an offsite backup for those who already use Time Machine locally.

Shared Passwords

The final area of concern surrounded passwords. I don’t know why, but JP and Gretel had never previously made the jump to a password manager. Part of that may have been JP’s idiosyncratic notetaking habits and Gretel’s excellent memory (when signing up for Backblaze, she was able to rattle off her entire American Express credit card number, expiration date, and CVC code with no difficulty). Nonetheless, Gretel was aware that she might not remember a one-off password or fact, so she fell back on handwritten reminders on sheets of notebook paper. Similarly, though more digitally, JP maintained a Word document with coded notes that described his passwords for different sites such that only he or someone who knew him well would be able to figure out the passwords. He had recently shared that document with family members but was aware that better solutions existed.

Moving elderly people to a password manager worries me. Password managers are better in every way—they’re faster, easier, more secure, more easily shared, and a boon for multiple device use—but they require learning an entirely new way of logging into websites, which seems to be tough. If a password manager causes more login friction than it saves, it will become more trouble than it’s worth.

Initially, I was thinking it would make more sense to help them come up with a better low-tech solution for backup and set Google Chrome to save passwords for them, but JP was insistent on setting up LastPass and sharing it with members of his family. We did that, and I showed him how LastPass asks to record newly created or updated logins, but I have some trepidation that it may not work out long-term. It’s possible that Apple’s Passwords and iCloud Keychain would have been a viable alternative, particularly with Apple’s account recovery contacts and Legacy Contacts, but Apple’s solution lacks the sharing features of LastPass and 1Password that make them compelling to families who might need to access the accounts of relatives who become incapacitated or pass away.

The ultimate solution is of course passkeys, which are both easier and more secure than passwords, but I fear that older folks will have trouble adjusting to yet another new authentication system (see “Why Passkeys Will Be Simpler and More Secure Than Passwords,” 27 June 2022). If JP and Gretel are at all representative of their generation, the biometric aspects of passkeys may not be as much of a win for older people as well—Touch ID fails for both of them, and I’ve seen suggestions that fingerprint scanning accuracy decreases with age due to skin becoming smoother and less elastic. Face ID shouldn’t suffer such issues, but plenty of Apple devices continue to rely on Touch ID.

So, again, it looks like Apple is moving in the right direction with password management, passkeys, and recovery options, but it may be too late for those who lack compatible hardware or for whom a new way of authenticating may be overly challenging.

Why Passkeys Will Be Simpler and More Secure Than Passwords

Apple has unveiled its version of passkeys, an industry-standard replacement for passwords that offers more security and protection against hijacking while simultaneously being far simpler in nearly every respect.

You never type or manage the contents of a passkey, which is generated when you upgrade a particular website account from a password-only or password and two-factor authentication login. Passkeys overcome numerous notable weaknesses with passwords:

- Each passkey is unique—always.

- Every passkey is generated on your device, and the secret portion of it never leaves your device during a login. (You can securely sync your passkeys across devices or share them with others.)

- Because passkeys are created using a strong encryption algorithm, you don’t have to worry about a “weak” password that could be guessed or cracked.

- A website can’t leak your authentication credentials because sites store only the public component of the passkey that corresponds to your login, not the secret part that lets you validate your identity.

- An attacker can’t phish a passkey from you because a passkey only presents itself at a legitimately associated website.

- Passkeys never need to change because they can’t be stolen.

- Passkeys don’t require two-factor authentication because they incorporate two different factors as part of their nature.

After a test run with developers over the last year, Apple has built passkey support into iOS 16, iPadOS 16, macOS 13 Ventura, and watchOS 9, slated for release in September or October of this year. These operating systems will store passkeys just as they do passwords and other entries in the user keychain, protected by a device password or passcode, Touch ID, or Face ID. Passkeys will also sync securely among your devices using iCloud Keychain, which employs end-to-end encryption—Apple never has access to passkeys or other iCloud Keychain data.

Best of all, perhaps, is that Apple built passkeys on top of a broadly supported industry standard, the W3C Web Authentication API or WebAuthn, created by the World Wide Web Consortium and the FIDO Alliance, a group that has spent years developing approaches to reduce the effectiveness of phishing, eliminate hijacking, and increase authentication simplicity for users. Apple, Amazon, Google, Meta (Facebook), and Microsoft are all FIDO board members, as are major financial institutions, credit card networks, and chip and hardware firms.

Many websites and operating systems already support WebAuthn via a hardware key like the popular ones made by Yubico. You visit a website, choose to log in using a security key, insert or tap a button on the hardware key, and the browser, operating system, and hardware key all talk together to complete the login. A passkey migrates the function of that hardware key directly into the operating system—no extra hardware required. Websites that already support hardware-based WebAuthn should be able to support passkeys with little to no effort, according to Apple.

Before we get started, note that Apple writes “passkey” in lowercase, an attempt to get us to use it alongside password, passcode, and passphrase as a common concept. Google, Microsoft, and other companies will offer compatible technology and may also opt for the generic passkey name. While new terminology can cause confusion, “passkey” is better than the more technically descriptive “multi-device FIDO credentials,” which doesn’t exactly roll off the tongue.

Let’s dig in to how passkeys work.

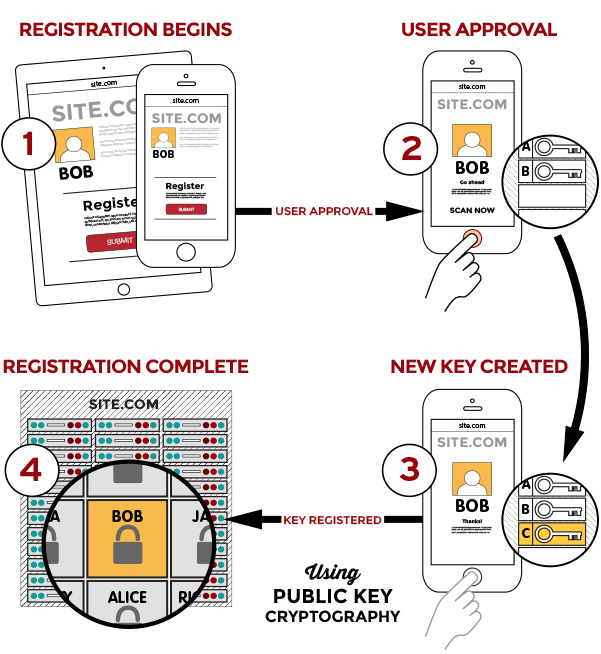

Passkeys Bring the Benefits of Public-Key Cryptography to Everyday Logins

Passkeys rely on public-key cryptography, something we’ve been writing about at TidBITS for nearly 30 years. With public-key cryptography, an encryption algorithm generates a secret that’s broken into two pieces: a private key, which you must never disclose, and a public key, which you can share in any fashion without risk of exposing the private key. Public-key cryptography underpins secure Web, email, and terminal connections; iMessage; and many other standards and services.

Anyone with a person’s public key can use it to encrypt a message that only the party who possesses the private key can decrypt. The party who has the private key can also perform a complementary operation: they can “sign” a message with the private key that effectively states, “I validate that I sent this message.” Crucially, anyone with the public key can confirm that only the private key’s possessor could have created that signature.

A passkey is a public/private key pair associated with some metadata, such as the website domain for which it was created. With a passkey, the private key never leaves the device on which it was generated to validate a login, while a website holds only the corresponding public key, stored as part of the user’s account.

To use a passkey, the first step is to enroll at a website or in an app. You’re likely familiar with this process from any time you signed up for two-factor authentication at a site: you log in with existing credentials, enable 2FA, receive a text message or scan a QR code into an authentication app or your keychain (in iOS 15, iPadOS 15, and Safari 15 for macOS), and then verify your receipt.

With a passkey, the process is different. When you log in to a website offering passkey authentication, you will have an option to upgrade it to a passkey in your account’s security or password section. The website first generates a registration message that Apple’s operating systems will interpret—it happens at a layer you never see. In response, your device creates the public/private key pair, stores it securely and locally, and transmits the public key to the website. The site can then optionally issue a challenge for it and your device can present it to confirm the enrollment.

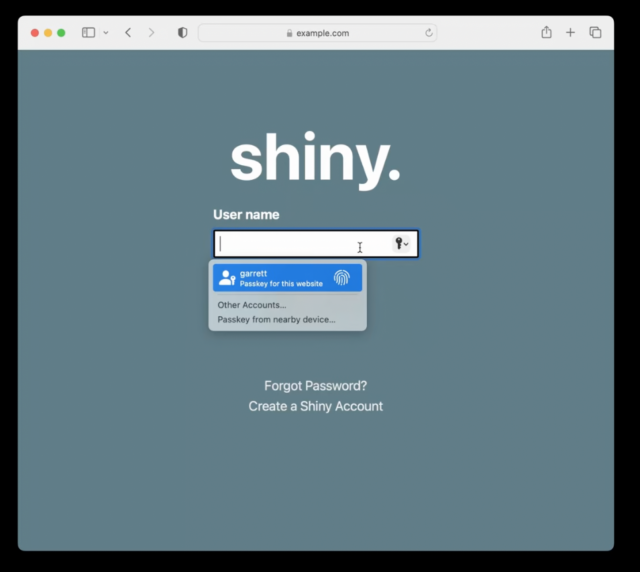

On subsequent visits, when you’re presented with a login, your iPhone or iPad will show the passkey entry in the QuickType bar and Safari in macOS will show it as a pop-up menu. In both cases, that’s just like passwords and verification codes today. As with those login aids, you’ll validate the use of your passkey with Touch ID, Face ID, or your device passcode, depending on your settings.

Behind the scenes, your request to login via a passkey causes the site server to generate a “challenge” request using the stored public key. Your device then has to build a response using your stored private key. Because you initiate a passkey login by validating your identity, your device has access to your passkey’s private key when the challenge request comes in and can respond to the challenge without another authentication step. The server validates your device’s response against your stored public key, ensuring that you are authorized for access. If it all checks out, the website logs you in.

A passkey replaces two-factor authentication, and it’s worth breaking down why, as it seems counter-intuitive: how can a single code held on a device provide distinct aspects of confirmation? The rubric for multiple security factors is usually stated as at least two of “something you know, something you have, or something you are.” A passkey incorporates at least two of those:

- Something you know: While commonly thought of as a password, the “know” part is really any fixed piece of information you possess. Think of a 20-character randomly generated password stored in your password manager. Do you “know” that? Yes, in the sense that it’s retrievable exactly as entered.

- Something you have: Because passkeys are locked to devices, you prove your possession of a device by unlocking the passkey: no device, no passkey.

- Something you are: Although passkeys don’t require biometric authentication using Face ID or Touch ID, it’s an option. Apple always lets you use a device passcode to backstop Face ID or Touch ID, so it’s a blurred line with “something you know” compared to a dedicated biometric device with no fallback option.

Think for a moment about the advantages here. A passkey:

- Resists phishing: As with passwords and verification codes, your device will only present a passkey in QuickType or as a pop-up menu option when on a website’s specific domain associated with the passkey. An attacker can’t fool you into entering a passkey on a deceptive site, as can be done with a password.

- Prevents reuse of a stolen key on other accounts: Because each passkey is unique to its associated website, even if the site suffers a security breach, the only credential that can be stolen is your public key. That public key is useless to help a thief log in as you at another site as they lack your private key to answer the login challenge.

- Blocks damage from malicious code injection on a website you visit: A malicious party can often “inject” malicious JavaScript onto an otherwise benign page. It has happened at times even to major websites, usually due to poorly vetted malicious ads delivered automatically through self-service advertising networks. A website that falls prey to just a front-end attack on its HTML and scripts wouldn’t allow the attacker to produce a valid challenge request for your device’s passkey. The site would also have to suffer from a back-end compromise of its server code for account information to be at risk, at which point the site’s data is probably fully compromised anyway.

- Blocks guessing, identity searching, brute force: Because every passkey has a super-complex secret, an attacker can’t successfully guess or brute force your access to a site.

- Eliminates 2FA hijacking: Because passkeys don’t have a second factor, they aren’t vulnerable to SMS hijacking and interception, site impersonation and phishing, and other techniques to acquire a second factor.

Apple stores each passkey as just another entry in your keychain. If you have iCloud Keychain enabled, the passkeys sync across all your devices. (iCloud Keychain requires two-factor authentication enabled on your Apple ID; Apple hasn’t said if passkeys will replace its internal use of 2FA for its user accounts.)

You can share a passkey with someone else using AirDrop. This means you have to be in proximity to the other person, another element in security. The details are shared through end-to-end encryption, allowing the private key and other data to be passed without risk of interception. Apple hasn’t provided much more detail than that AirDrop sharing is an option, so there may be other provisos or security layers.

Because passkeys replace passwords and a second factor, you may be reasonably worried at this point about losing access to your passkeys if you’re locked out of your Apple ID account or lose all your registered devices. Apple has several processes in place for recovering Apple ID account access and broad swaths of iCloud-synced data. For an Apple ID account, you can use Apple’s account recovery process or an account Recovery Key. For iCloud data, if you’ve enabled the friends-and-family recovery system, iCloud Data Recovery Service, you can use that to re-enable access. After you recover account access, Apple has an additional set of steps that enable you to retrieve iCloud Keychain entries: it involves sending a code via SMS to a registered phone number and entering a device passcode for one of the devices in your iCloud-synced set.

This is all a fabulous reduction in the potential for successful attacks against your Internet-accessible accounts. But there’s more: Apple isn’t building yet another walled garden. Instead, passkeys are part of a broad industry effort with which Apple says its implementation will be compatible.

Passkeys Are an Industry Standard, Not a Proprietary Technology

Apple built its passkey support on top of the previously mentioned WebAuthn standard, which describes the server side of how to implement a Web-based login with public-key cryptography. FIDO created standards for the client side of that equation and calls the combination of its protocol and WebAuthn FIDO2. Apple developed its own client-side approach that’s compatible with standard WebAuthn servers and should be interchangeable with other companies’ rollouts of passkeys. Google, Microsoft, and Apple made a joint announcement in May 2022 committing to this approach, too.

In Apple’s passkey introduction video for developers, engineer Garrett Davidson emphasized Apple’s commitment to compatibility, saying:

We’ve been working with other platform vendors within the FIDO Alliance to make sure that passkey implementations are compatible cross-platform and can work on as many devices as possible.

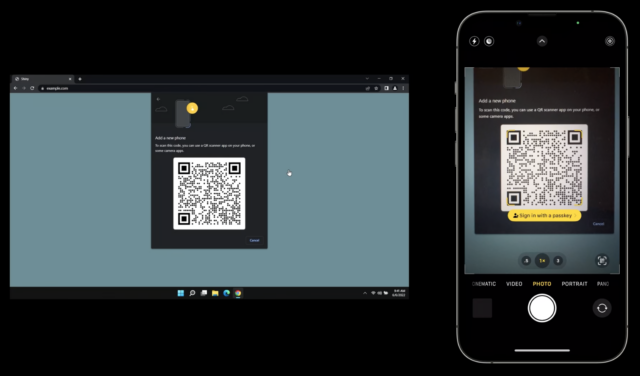

He then demonstrated using a passkey on an Apple device to log in to a website on a PC, showing how a QR code could be used to enable a passkey login to one of your accounts on a device or browser that’s not connected to your existing devices or ecosystem.

Here’s how you might log in to a passkey-enabled account on someone else’s PC using your iPhone with your passkey as the authenticator. During the login, you can opt to add a device instead of entering a passkey or other authentication in the browser. The website’s server generates a QR code that includes a pair of single-use passwords—they’re generated just for that login and used in the next step for additional validation. (Note that the device with the browser could be any passkey-supporting operating system and device. The authenticating devices might be limited by Apple or other companies to a smaller set, much like you can only use an iPhone to confirm Apple Pay in Safari on a Mac, not a Mac with Touch ID to confirm Apple Pay from an iPhone.)

The PC in our example also starts broadcasting a Bluetooth message that contains the information needed to connect and authenticate directly with the server. Scan that QR code on your iPhone, and the iPhone uses an end-to-end encrypted protocol to create a tunnel with the PC’s Web browser using the keys shown in the QR code. (This encrypted connection isn’t part of the Bluetooth protocol, by the way, but data tunneled over Bluetooth; Bluetooth doesn’t incorporate the necessary encryption strength.)

This Bluetooth connection provides additional security and verification by offering out-of-band elements, or details that the PC isn’t presenting to the device that’s providing authentication—here, your iPhone. Because Web pages can be spoofed for phishing attacks, the Bluetooth connection provides a device-to-device backchannel for key details:

- Server addresses: The QR code doesn’t tell the iPhone what server (or list of servers) it can connect to for the actual passkey connection. That prevents a browser from providing malicious information.

- Key validation: The successful creation of an end-to-end encrypted two-way session over Bluetooth using the keys in the QR code enables the iPhone and PC to confirm that the QR code the browser delivered and the iPhone scanned are identical. (Apple hasn’t yet provided full details on this stage. The operating system clearly generates the QR code based on a request from the browser, and the browser can’t sniff the Bluetooth connection. So a front-end attack that displayed a malicious QR code wouldn’t work, as the PC and iPhone communicate without the browser in the loop.)

- Proximity: Connecting over short-range Bluetooth demonstrates, with confidence, that the PC and iPhone are near each other.

This broad device and platform compatibility lets you maintain the same degree of passkey security and simplicity without downgrading to a weaker method for login when accessing your account using other people’s devices. Whenever there’s a way to force a weaker login method, malicious parties will exploit that via phishing, social engineering, or other interception techniques. (Providing a second factor via an SMS text message versus a verification code is a prime example of a weaker backup approach that has been exploited.) In fact, until passkeys can be used exclusively, password-based logins will have to remain available, and they’ll remain vulnerable.

There might be some usability hiccups as passkeys roll out, but they shouldn’t be widespread. It’s possible, for instance, that some WebAuthn server components will need to be updated or that Apple will have to add more edge cases to its framework to encompass how things work in the wild.

But imagine a world in which you can securely log in to websites using any current browser on any device running any modern operating system, without having to create, remember, type, and protect passwords. It’s relaxing just to think about.

The main question that remains unanswered is how portable passkeys will be among ecosystems: can I use iOS and Android and Windows and share a passkey generated on one among all three? Given that Apple has built an AirDrop-sharing method for passkeys, I hope FIDO’s broad compatibility includes sharing passkeys among operating systems, too.

A Return to Security through Proximity

Passwords have provided an uneasy security compromise since their introduction decades ago when multi-user computing systems began to require protection. Passwords are patently imperfect, a relic of an age when physical proximity provided the first level of protection, something rendered moot by the Internet.

In an effort to answer some of the weaknesses in a password system, two-factor authentication was grafted on to require that you had something besides a password, something that required holding or being near an object to validate your right to log into a computer, service, or website. But because 2FA starts with an account password and uses a second method that can be subject to compromise or phishing, it remains a patch applied to a damaged wall.

The passkey is a modern replacement for passwords that rebuilds the security wall protecting standard account logins. Proximity—in the form of the device that stores your passkeys—is a powerful tool in reducing account hijacking and interception. Passkeys may seem scary and revolutionary, but they’re actually safer and, in some ways, a bit old-fashioned: they’re a bit of a throwback to a time when having access to a terminal provided proof you were authorized to use it.