Apple Addresses Location Controversy Questions

Responding to the tempest in a teapot surrounding the discovery that the iPhone records certain location data, Apple last week issued a clearly written Q&A that addresses the primary questions asked by users. Later that day, Steve Jobs, Phil Schiller, and Scott Forstall talked to Ina Fried of All Things Digital (run by the Wall Street Journal) about the situation; the transcript is well worth reading.

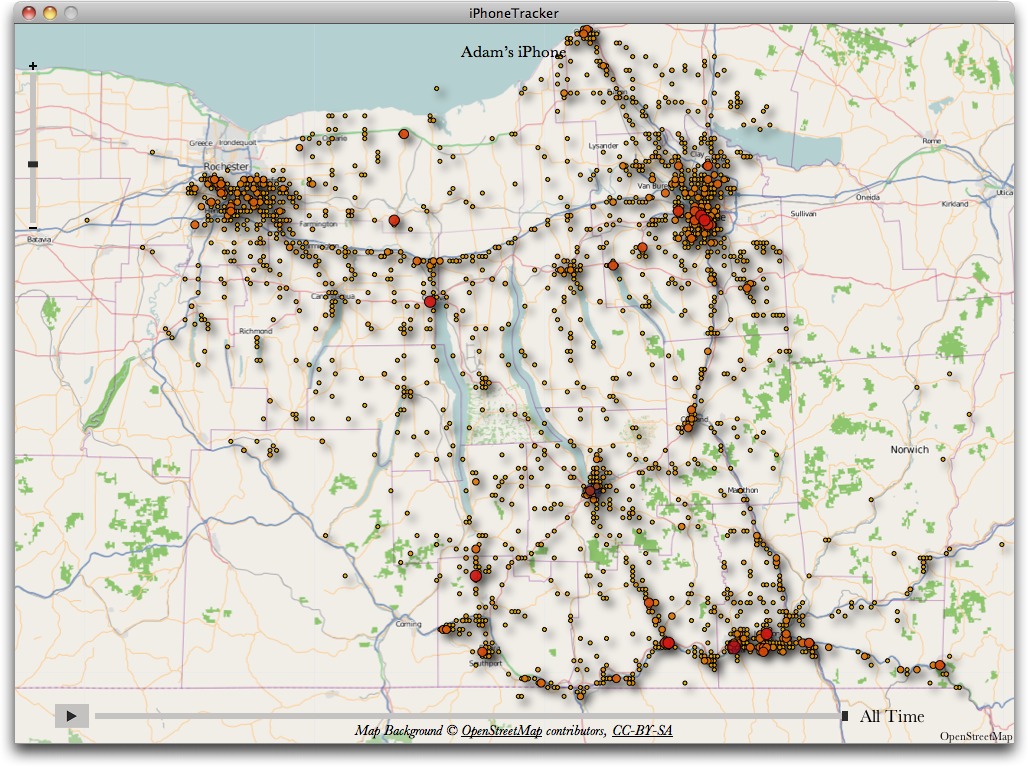

For those who have been lucky enough to miss the fuss, it was determined that some form of location data was being stored on the iPhone, which led to hysterical news articles claiming that Apple was tracking the locations of iPhone users. This data included geographic coordinates that, when plotted on a map, seemed to provide a long-term record of your movements.

The hysteria continued even after saner heads, like David Pogue of the New York Times, pointed out that the information wasn’t being transmitted to Apple or anyone else and that all cell phone carriers track and record every movement of their subscribers. Nor did it make a difference that the information extracted from your iTunes backups (which was extremely hard to get until the iPhoneTracker application was created to display it) was often clearly different from where you actually were. The greatest risk might have been someone (law enforcement or a technically savvy stalker)

obtaining your phone and having what seemed to be a record of your location over time.

Although I strongly recommend reading Apple’s Q&A, it can be summarized as follows.

Apple is not tracking the location of your iPhone. Nor is your iPhone logging your actual locations. Instead, iOS maintains a database that represents a subset of Wi-Fi hotspots and cell towers in the general vicinity of a current location. The point of this database is to help the iPhone calculate its location more quickly when requested, both by avoiding a round-trip query over a mobile or Wi-Fi network to look up this information, but also to help a GPS receiver, if one is present (as one is on all iPhones since the iPhone 3G and all 3G versions of the iPad).

When starting fresh, a GPS receiver by itself can take up to 12.5 minutes to receive the full set of information about all the satellites it can see and obtain a location. If the GPS receiver knows its approximate location, that time can be reduced to 30 to 60 seconds. But with Assisted GPS (AGPS), which Apple and other smartphone companies employ, the time to acquire a satellite lock can be reduced to just a few seconds by using rough Wi-Fi or cell tower location information (the large blue circle in the Maps app, for instance) to help interpret fragments of GPS satellite signals. (TidBITS editor Glenn Fleishman wrote a long explanation of AGPS for Ars Technica

in 2009, if you want more detail.)

There is little more frustrating than sitting in a car and waiting for your GPS navigation app to figure out your location so you can start driving in unfamiliar environs. That’s where AGPS comes in, and it’s part of the explanation for why Apple caches location data.

The iPhone does transmit — in an anonymous and encrypted form that Apple cannot use to identify you or your position — the locations of nearby Wi-Fi hotspots and cell towers back to Apple, where they are added to a massive crowd-sourced database. Apple used to get this sort of data from Skyhook Wireless, the firm that pioneered Wi-Fi positioning, but switched to its own network data gathering with the first iPad release, and with iOS 4.0 for all other devices.

The iPhone downloads and caches an appropriate subset of that database to aid in location calculations, and it’s this cached subset that is backed up in iTunes and read by iPhoneTracker, which accounts for the locations that don’t correspond with where you’ve actually been. For instance, check out the screenshot to see that, yes, I’ve driven around a bunch of upstate New York for cross country and track races. But I can guarantee that I’ve never been to lots of these spots.

The only location data that Apple collects and shares with other companies comes from iAds, which can use location as a factor in targeting ads. That information will be shared, but only if you explicitly approve when an iAd asks for your current location (Apple gives the example of a user requesting that an ad locate the nearest store).

Apple did for the first time reveal that it is now “collecting anonymous traffic data to build a crowd-sourced traffic database with the goal of providing iPhone users an improved traffic service in the next couple of years.” Although the Q&A isn’t clear about this, it’s likely the same sort of current road speed data captured by Android phones and some cell-connected standalone GPS navigation devices. Live traffic data can be integrated and then fed back out to provide real-time road status even on relatively low-traffic streets.

Now, all this said, Apple also acknowledged that they have identified a number of bugs in how location services were working. A free iOS update within the next couple of weeks will:

- Reduce the size of the crowd-sourced Wi-Fi hotspot and cell tower database cached on the iPhone. Previously, the iPhone was storing as much as a year’s worth of the subsets of Apple’s crowd-sourced location database. Apple says that was a bug, and after the update it will store only the last seven days’ worth of this data.

- Cease backing up this cache. There’s no reason to back up this data, since it’s just a cache to speed up location calculations, and can easily be downloaded again. After the update, this data will no longer appear in the iTunes backup files.

-

Delete this cache entirely when Location Services is turned off. This was another bug; even if you turned off Location Services, the iPhone could continue updating its cached subset of the Apple’s location database. Obviously, with Location Services off, there’s no reason for the iPhone to maintain this cache at all, and it won’t in the future.

Finally, Apple promised that the next major release of iOS would encrypt the cache on the iPhone so it couldn’t be used to determine even the general part of the world the user was in. It’s unclear if this means iOS 4.4 or iOS 5.

The only remaining question is if there’s anything more to this situation than Apple is letting on, and honestly, I doubt it. Apple is a business, and businesses exist to make money. Unless someone can point to a legal way Apple could make a boatload of money from location data without in any way endangering the massively lucrative iPhone market, assuming that Apple is up to no good here is pure conspiracy theory.

Yes, Apple could have designed the system to encrypt this data to start, and yes, Apple could have caught the bugs they’ve now identified and acknowledged earlier, but minor technical mistakes happen in all sufficiently complex systems. More important is how they’re resolved — and how quickly — and it appears that Apple is doing the right thing with the forthcoming iOS update.

Now perhaps privacy watchdogs can turn their attention to the very real breach of Sony’s PlayStation Network, from which hackers were able to steal personal information about tens of millions of subscribers, possibly including credit card data.

I believe you've slightly missed the point of iPhoneTracker's apparent inaccuracy. The software deliberately randomises the points it shows on the map according to its website.

http://petewarden.github.com/iPhoneTracker/#8

Yes, it says that, and it also says that it picks up towers that are "several miles" away inadvertently, but Apple's claim is that the data is entirely unrelated to your location and is instead the location of cell towers and Wi-Fi hotspots. Perusing my personal data backs up Apple's claim, since there's only one marker within a mile of my house, on a dead-end road I'm certain my iPhone has never been on.

Ah yes, so iPhoneTracker obfuscates locations that weren't where you were anyway. Splendid!

I'm very nearly thinking meanwhile that this was a deliberate act to muddy the waters. I've removed that rounding and while the locations where a bit different then before they still were in no way nearer to my true location. But by modifying the displayed plots nobody really knew what was actually IN there and naturally people assumed the data was off only because of this rounding.

Really, I took one long look at the raw data and the table layout and at the actual locations and was 99& sure this was cell tower and WiFi station locations, not the locations of the iPhone.

From Apple: "... generated by tens of millions of iPhones sending the geo-tagged locations of nearby Wi-Fi hotspots and cell towers in an anonymous and encrypted form to Apple."

This is the part that worries me. I have a hard time believing that my phone, upon determining its location and Wi-Fi/cell tower neighbors, instantly sends the information to Apple and immediately erases it. If I were building this system, I would stick the data in a cache and upload it periodically. Does such a cache exist? If so, where? What's in it and for how long?

Looking at the consolidated.db database itself on my Mac (using instructions here http://petewarden.github.com/iPhoneTracker/ ) I see tables for both CellLocation and CellLocationHarvest. I wonder if the latter is how it harvests data from my phone. Interestingly, it's empty.

Screen shot of tables in consolidated.db database: http://www.flickr.com/photos/jamescookmd/5663346236/in/photostream

Also of interest: I'm not sure how these SQLlite databases order their records, but my home router is the very last entry in the WifiLocations table, which appears to be ordered by timestamp. Even if the vast majority of consolidated.db is data from Apple's crowd-sourced system, if there's an easy way to find to find someone's home router, you're most of the way to finding their real-world identity and location.

Adam

I do not understand why you are playing down an issue that – in my view legitimately – has alerted data protection officials all over the world.

So, my iPhone is not tracking my exact location. But it tracks a bubble of WiFi hotspots and cell towers around me that allowed me to reconstruct my travels in Switzerland, Germany and Italy over the last months.

So, Apple is doing this with good intentions so that I can faster locate myself. But good intentions are not good enough. Collecting location information requires my consent that I was never asked for – and I cannot even switch off collecting or erase the collected data.

So, Apple is storing this information unencrypted on my iPhone which is safe as long as nobody steals my iPhone. How about US law enforcement agents who have been known to confiscate electronic devices when you enter the US?

So, according to Apple this is a bug. Recall that Google claimed the same when it was found out that on their street view tours they not only took photos but also collected information on WiFi hotspots and cell towers. Considering that Apple's business relies a lot on location information and that they recently submitted a patent to combine location information with financial transactions and events like taking a photo, I have a hard time to believe Apple.

I start to ask myself: Could it be that Europeans have a different view on privacy than US citizens?

--- nef

In general Europeans absolutely do have a different view than USians on privacy and they have the laws to prove it. But I don't think that's so much the issue because I do believe that this case (and the Google case you mention) is one of a programmer's error in judgement rather than a corporate plan for this data without consideration of the user.

Programmers do not apply the question "will this affect the user's privacy?" to every bit of code they write. What privacy laws can do is provide companies with a legal obligation to care and therefore a financial incentive to care. Companies can train programmers to take more care about potential privacy problems but that's of limited effectiveness. What's necessary is to have employees who specifically review software and other products as a part of the existing Quality Assurance process for potential privacy problems.

BTW, Google didn't claim they accidentally recorded information about wifi access points, that was quite intentional and I don't think was a problem even under European laws. The problem was the collection software stored not only the broadcast access point names and unique identifiers (necessary for using them as location landmarks for triangulation) but also snippets of sent and received wifi packets and if the access point was not set to be encrypted, private information could be exposed.

I really do think it's a bug, or at least an unintentional side effect, since Apple has nothing to gain from it and a whole lot to lose.

So it's like most other security situations - something was discovered that could have had the potential for harm, and it's conceivable that it did in some very small ways (given the many millions of iPhones in use), and Apple is fixing it so that it can't be exploited in the future.

Heck, this time we even got some explanation. But I really don't see it as a huge deal, especially given the fact that cell carriers (who can be subpoenaed, and who can have disgruntled or dishonest employees) have long been tracking and recording much more data about your whereabouts.

I think we're being realistic about this. You have to jailbreak the phone and extract a file. This means that someone has to have physical access to your phone and/or your backups in iTunes, and the means and knowledge to do the extraction. (Using the tool that was released is useful, but it purposely introduces errors, and so you have to modify that code to get the exact information.)

It seems very much like a few different bugs, and given that the information was never transmitted to Apple, I don't see a problem with their plans to fix the bug.

Google's "bug" was collecting publicly transmitted unencrypted data, which I also don't think was that big a deal because it was snippets, and it was data that any person sitting there could have gathered, and Google didn't put any of the data to use.