Small Pipes and High Bills: Keeping Bandwidth Use in Check

Our computers chat all day long with Internet servers near and far, and we can usually remain blissfully unaware of how much data they send and receive, so long as we’re using a high-speed Internet connection. This is a relatively recent development — it wasn’t all that long ago that we relied on 56 Kbps (or slower!) modems for our Internet connectivity, meaning our computers had to assume that Internet connectivity was both intermittent and constrained. With broadband Internet connections, computer makers first made the transition to assuming always-on connectivity, and in the past decade those assumptions have evolved into software and services expecting an always-big bandwidth pipe.

But those assumptions aren’t always true even now, because the more mobile we become, the more likely we find are to ourselves in places in which we either have too little bandwidth available or are paying too much for the bandwidth our computers want to consume. An automated backup agent, a sync service program, background email checking, and even Apple’s automatic software updates could leave us frustrated by network performance or shocked by a too-large bill.

Limited bandwidth situations are also becoming a tragedy of the commons, where a small number of people can ruin it for everyone else. Public Wi-Fi networks, whether in hotels, at conference centers, in coffee shops, or on an airplane or cruise ship, are increasingly becoming less reliable to use, thanks in part to heavier use of video and the large number of smartphones and iPads. Amtrak even warns users of this problem with their “continuous” Wi-Fi service, as I found while working on this article during a train trip between Seattle and Portland.

But our computers are also to blame, due to software assuming it has an always-available, high-speed Internet connection. The hotel Wi-Fi that used to be sufficient for checking email and editing files in Google Docs now struggles with even such low-bandwidth tasks, thanks to all the other people watching Netflix, backing up via CrashPlan, and synchronizing files via Dropbox. These scenarios aren’t hypothetical — Adam Engst found his hotel Internet connectivity too slow to use at times during Macworld | iWorld in

January 2012, and Joe Kissell experienced huge frustration when sharing on-ship Wi-Fi during a recent MacMania river cruise (the Internet connection in the latter case came from multiple bonded 3G cellular data connections). The CSS guru Eric Meyer told me about a 50 Mbps connection used at his An Event Apart design conference being accidentally hogged by a speaker’s corporate backup software kicking in.

And while you can sometimes carve out sufficient bandwidth for your needs by switching to a mobile broadband connection and tethering your computer, usage limits on mobile broadband mean that you have to start counting bytes. In the United States, cellular providers now typically levy surcharges when you exceed a fixed amount of data in a plan, whether 300 MB, 2 GB or 10 GB. In many other countries, instead of charging overage fees, mobile carriers throttle accounts to between 64 and 256 Kbps after a threshold is reached.

(I won’t be discussing a related situation, which is how to deal with permanently low-bandwidth scenarios, whether in the American hinterlands where dial-up modem or low-speed satellite are the only options, or in developing nations in which expensive low-speed cellular connections or dial-up modems over pricey landlines are all that are available. If there’s interest, we’ll look into a separate article about that topic in the future.)

In the rest of this article, I’ll explain how, when you find yourself in one of these low-bandwidth or high-price situations, you can figure out which applications are blindly consuming bandwidth and then throttle, pause, or quit them. Then I’ll share some thoughts about a proposed utility that could help us automatically reduce our bandwidth use when desired.

Find and Track the Talkers — The main obstacle I ran across in researching this topic was determining how best to figure out which of the many daemons, background applications, and Apple components transfer more than a handful of kilobytes per day. The obvious culprits were easily found, but a real-world Mac OS X system is full of software that fires up as needed in the background, and that’s easily overlooked. Tools for ferreting out such software abound, but none is perfect.

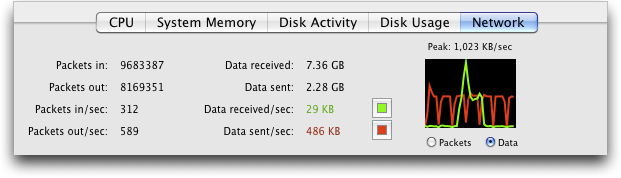

You can use Mac OS X’s Activity Monitor (found in /Applications/Utilities) to see bandwidth consumption as it happens. After launching, click the Network button at bottom right and watch the red and green lines on the graph. But the graph doesn’t tell you what program is burning up the wire, just that transfers are happening.

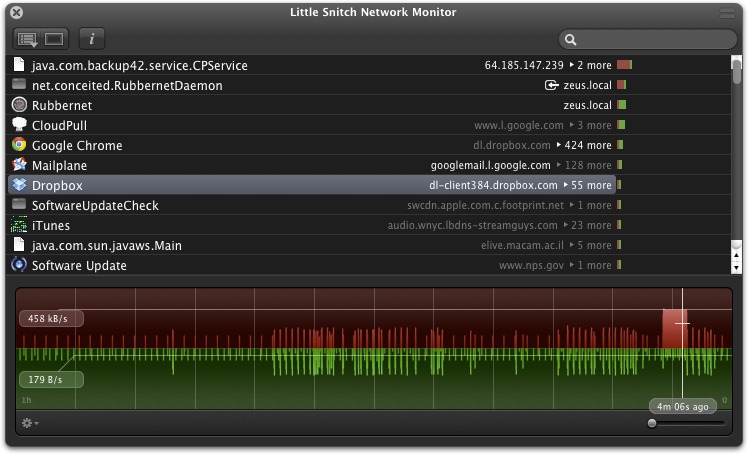

The $34.95 traffic monitoring utility Little Snitch, which I advise the use of later as one way to catch and halt unwanted usage, has an attractive network monitoring display that shows consumed bandwidth over time and lets you drill down to usage by program and domains accessed by that program. But there’s no additional information you can extract. You can watch the tool to see which apps are being chatty (for the previous 60 minutes only) or review

the overall usage later, but not get details that might help shape the rules you set in it.

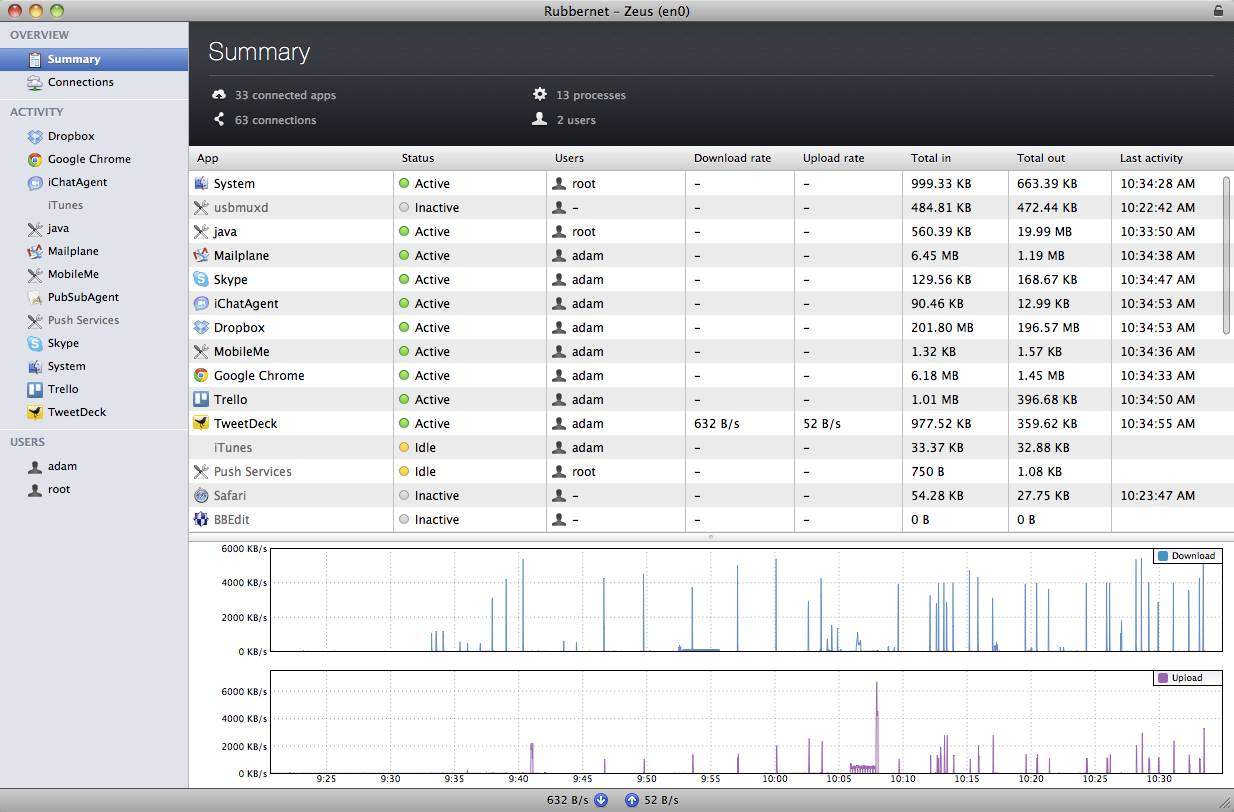

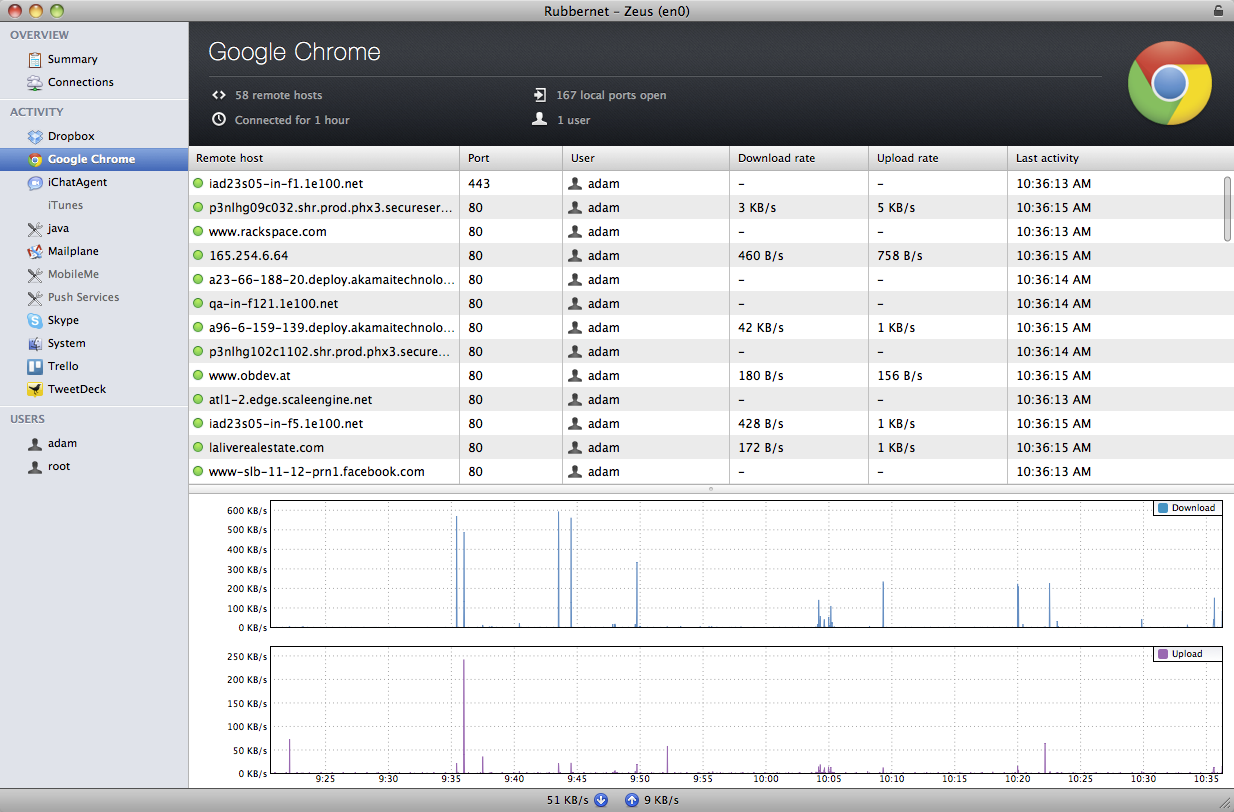

The best solution to this problem that we’ve found so far is Conceited Software’s Rubbernet, a €29.99 (roughly US$37) Mac OS X program with a 15-day free trial.

While Rubbernet is running, it summarizes all the traffic (sent and received) by every application, showing you the app name, whether or not it’s active, which user the app belongs to, the download and upload rates, the total data in and out, and the time of the last activity. Double-clicking an active app (or clicking it in the sidebar), shows you the remote host names, port used, user, download and upload rate, and last activity.

The Summary window is useful for identifying when significant amounts of data are being transferred, and then you can go to an app’s detail view to try to figure out what’s happening (by examining the remote host and port columns). This works well for bandwidth-intensive apps that are relatively obvious, like SkyDrive or Transmit. (A tip: Rubbernet’s “System” category includes a whole bunch of unrelated things — we found that it even included RSS checking in Safari, which explained some otherwise inscrutable domains

that were being pinged regularly.)

What Rubbernet doesn’t offer, though, is a historical view of this data, which disappears when the Mac sleeps or is restarted. That can make it tricky to understand certain events if you were otherwise occupied at the time. Rubbernet also omits past data consumption for inactive programs, making detailed analysis even harder. We’d like to see a future version of Rubbernet add the capability to maintain data for longer, and alert the user when certain transfer rates are exceeded, so you could investigate bandwidth

use while it’s happening, rather than just seeing later that it did happen.

If running a network monitoring utility is more effort than you’re willing to invest, you can still make some suppositions about what types of software will transfer non-trivial amounts of data. Once you’ve identified possible culprits, you can then throttle, pause, or quit them, as described later. The main types of software to watch out for are:

- Cloud-based synchronization services like Box, Dropbox, Google Drive, SkyDrive, and many others run in the background and constantly keep files up to date. If you’re sharing folders with collaborators, any changes they make will be pushed to your computer directly as well, which means that you could be bringing in significant quantities of data even when you’re not sitting at your Mac.

- Internet backup services like Backblaze, Carbonite, CloudPull, CrashPlan, Dolly Drive, Mozy, SpiderOak, and many others also run in the background, copying your changed files out to the cloud. Backup services may run on a schedule rather than continuously, making them a bit more predictable than synchronization services, but if you’ve made substantial changes, downloaded large files, imported photos or videos from a camera, or anything else that creates or changes lots of data, you will likely see spikes in usage.

-

Apple software updates can be an unpredictable source of significant data transfers. In the Software Update pane of System Preferences, you can set your system to download updates automatically whenever they’re available. While many of these updates are small, updates to Mac OS X and some of Apple’s applications can be in the 500 MB to 1 GB range. Software Update provides no indication that these downloads are happening until the Software Update application notifies you that updates are ready to be installed.

-

Various uses of iCloud can consume significant Internet bandwidth, perhaps without you realizing. For instance, Photo Stream in iPhoto could start downloading newly taken photos at any time. If you use iTunes Match and you play a song that isn’t stored locally, iTunes will stream it from iCloud in the background. Or, if you purchase content from the iTunes Store or the Mac App Store, that content may be downloaded automatically to multiple devices without any further interaction from you. As more programs start relying on iCloud for synchronization of files, we could start seeing non-trivial bandwidth usage occurring in the background as iCloud keeps all our devices in sync.

-

Google, because the company thinks in terms of Web-based applications, has set most, if not all, of its desktop applications to update automatically in the background. This prevents the user from having to think about updates, and protects users against bugs and security holes, but could prove troublesome if an update starts downloading while you’re in a low-bandwidth situation. Controlling when — and how often — Google Software Update checks for and downloads updates requires working in Terminal.

-

Some applications, such as Google Chrome and Firefox, can update themselves automatically, downloading a new version when you launch the app.

Once you’ve identified the software on your Mac that’s likely to transfer significant amounts of data, you can figure out some ways that you can limit bandwidth usage whenever you’re in a situation where unbridled transfers would be inappropriate.

Throttle, Pause, or Quit — Some applications that use data continuously may be throttled to reduce bandwidth usage, paused for a period of time or until you resume manually, or simply quit to prevent their activity entirely.

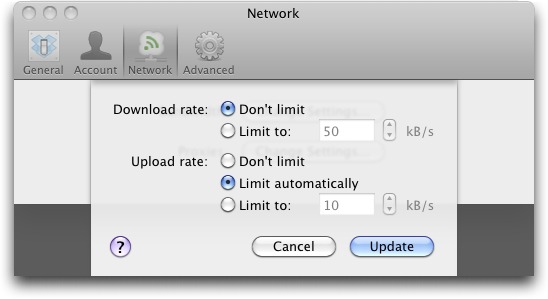

Throttling is the least extreme of the bandwidth-limiting solutions — when an app allows throttling, it lets you restrict its bandwidth usage. Throttling is best when you have an app that can do some useful work with limited bandwidth but which might try to consume significant bandwidth if not throttled. We’re aware of only two popular apps that offer throttling: Dropbox and CrashPlan.

- Dropbox: From the Dropbox menu, choose Preferences, click Network, and then click the Change Settings button for Bandwidth. You can limit upload and download rates separately.

-

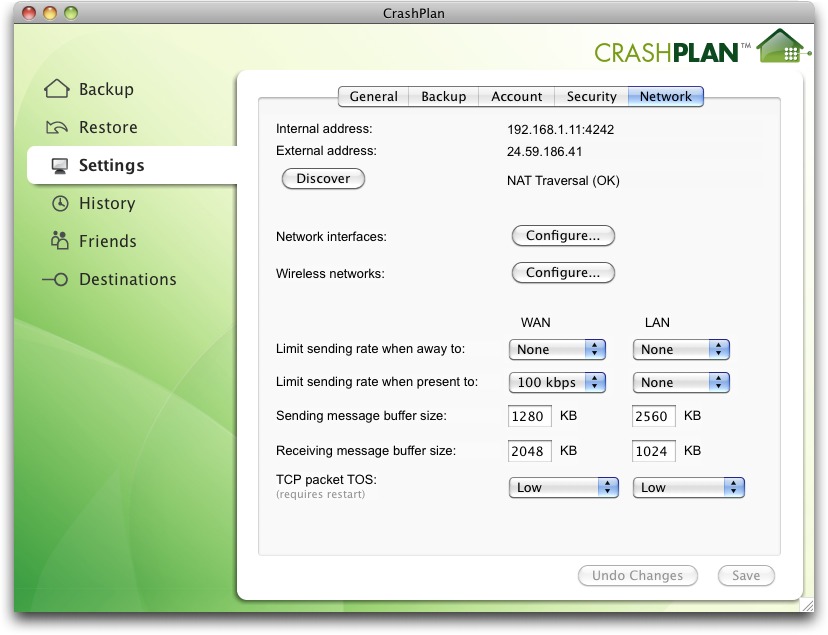

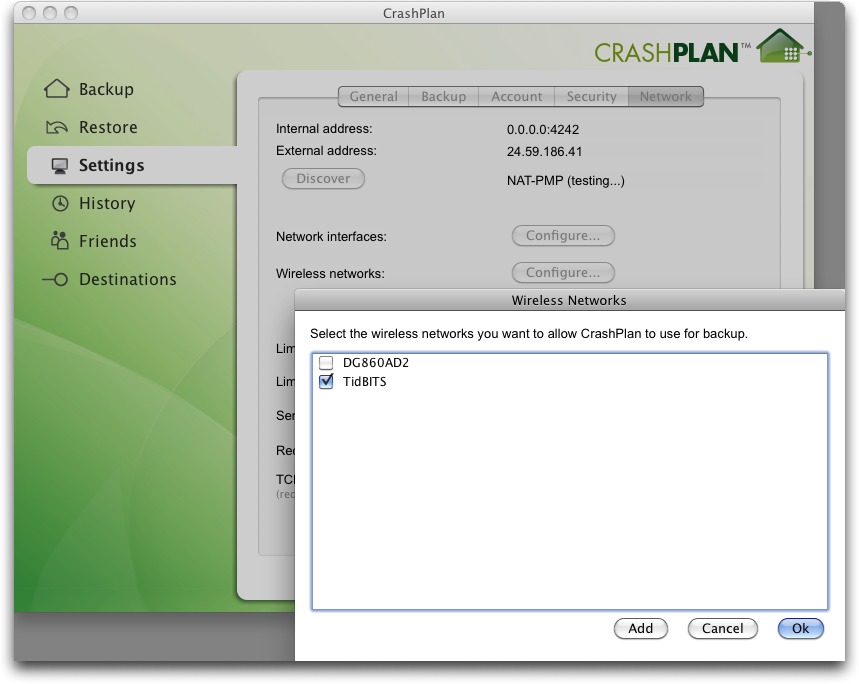

CrashPlan: In the CrashPlan app’s Settings screen, click the Network button. You can set rates in the Limit Sending Rate pop-up menus for the WAN (the remote connection to your own or peer backups or to CrashPlan Central). There’s little reason to limit LAN rates on most modern Wi-Fi or Ethernet networks.

Some less-common applications include such a feature as well. SpiderOak lets you limit the upload rate to a user-defined number of kilobytes per second; Dolly Drive lets you set a slider that represents a percentage of available bandwidth; and SugarSync offers a similar slider labeled Low, Medium, and High. (The new Google Drive and updated Microsoft SkyDrive lack throttling.)

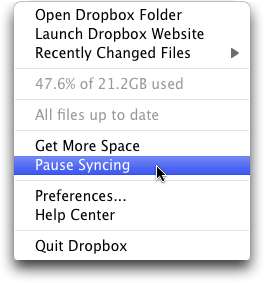

If throttling isn’t available, you might be able to pause the application’s data transfer activities entirely. Pausing is often more useful than throttling because then you know the app won’t be using any bandwidth at all. Be careful, though, since it’s easy to pause software while travelling, for instance, and then forget to re-enable it once you’re back home. (Adam caused some version control confusion by pausing Dropbox during January’s trip to Macworld | iWorld and forgetting to turn it back on later, thus working on what turned out to be an older version of a shared file.) Many network-intensive applications include a pause feature as a menu item or button in the interface; here’s how to pause Dropbox and CrashPlan

and various other types of programs:

- Dropbox: From the Dropbox menu, choose Pause Syncing. You’ll notice that the little green badge that indicates that Dropbox is fully synced disappears. To start syncing again later, choose Resume Syncing.

-

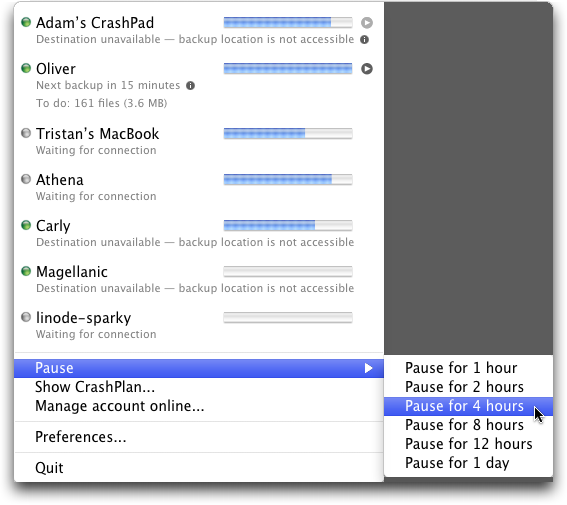

CrashPlan: To pause CrashPlan, you must enable the system-wide CrashPlan menu bar icon (click Launch in the CrashPlan app’s Settings screen) and then choose an amount of time to pause from the Pause submenu. If you want to start backing up again before the time elapses, choose Resume from the same menu. You can also run the CrashPlan app, double-click the house icon in the upper right corner to show CrashPlan’s Command window, and then type

pause; enteringresumerestarts backups.CrashPlan can also be set to work only on selected Wi-Fi networks, pausing otherwise: in the Settings screen, click the Network button, then the Configure button to the right of Wireless Networks. Select the checkbox next to the networks over which you want CrashPlan to work. Every new network to which you connect is automatically enabled, so you’ll want to come in here to disable low-bandwidth networks.

-

Email programs: Many email programs let you go offline or disable automatic checking through a menu item or a checkbox. You can opt for that, or, as is also common in many programs, set a maximum download file size threshold beyond which only the first part of a message is retrieved as a preview (an option with POP accounts) or just the message part without attachments (with IMAP accounts).

-

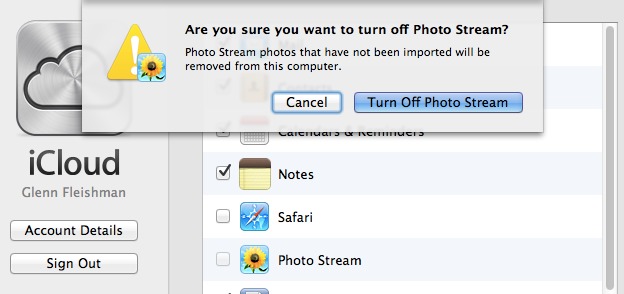

iCloud: For iCloud, Apple offers only a binary control with a major flaw that we hoped would be rectified in Mountain Lion (it’s not). You can disable iCloud services, like Photo Stream, Documents & Data, and Contacts, but Mac OS X will (with a warning before you proceed to turn the service off) delete the local copy of everything. For Photo Stream, it deletes all the photos in iPhoto that weren’t imported. For the others, your data is washed clean from the Mac, but can be synced again if you re-enable. Logging out of iCloud is even worse: it deletes all synced content on your computer.

Finally, for a good deal of software, quitting or disabling its network functionality is the only way to stop it from chattering incessantly. That can be tricky if the software doesn’t have standard menus with a Quit command, or at least an icon that appears in the Dock. If that’s not the case, try these approaches:

- A lot of applications that work primarily in the background provide a system-wide menu in the menu bar. Most such applications offer a Quit command, but it’s worth verifying in Activity Monitor that you can actually quit the background process that’s transferring data, and not just a companion application that provides the menu. If you don’t see a Quit command, try holding down Option before clicking the app’s menu bar icon to see if the menu reveals one.

-

Check System Preferences for a preference pane for the app that might contain otherwise non-obvious controls to stop, pause, or quit the service. Some applications may also install companion apps in the Applications folder for such purposes.

-

For Apple’s Software Update, open the System Preferences pane and uncheck the option to Download Updates Automatically.

-

Keep browsers from updating. Google Chrome will try to update itself in the background unless you restrict it via Google Software Update. Firefox may be set to auto-update as well; you can turn off its automatic updates in Firefox > Preferences > Advanced > Update.

-

Twitter clients now typically use Twitter’s streaming feed, which continuously polls and updates content. Although the overall bandwidth burden may be low, it could add up over time. Quit your Twitter client to ensure that it’s not consuming bandwidth.

-

As a last-ditch effort, look at the processes in Activity Monitor and quit any that you think might be transferring a lot of data. This is a brute force approach, and shouldn’t be used routinely because it could corrupt data, produce unexpected behaviors, or cause general instability. Plus, such daemons tend to restart themselves automatically, so quitting them manually is seldom successful for long.

As an alternative to quitting a particular program, you could also consider using Little Snitch to block its capability to communicate with the Internet. Starting with version 3 (available now in a preview release), Little Snitch lets you create and switch between profiles. You could, therefore, create a low-bandwidth profile in which no network traffic is allowed except for a few things you define, such as Web browsing via port 80 for http or 443 for https.

While using Little Snitch to block network traffic in a low-bandwidth situation isn’t the best use of an application firewall, it can be effective. Be aware that hobbling some applications in this way may cause them to throw up alerts repeatedly to tell you they can’t connect to the Internet.

Wishing for a Data Transfer Management Utility — It wouldn’t be that hard for a developer to write software to help users manage their bandwidth usage. (Apple could do so as well, but the fact that we don’t see such capabilities built into Mac OS X suggests that Apple isn’t interested.) What we need is a piece of software that combines monitoring, notification, and firewall capabilities. Such software should:

- Track bandwidth usage by protocol and application to help you discover which programs are transferring significant quantities of data.

-

Provide warnings when data transfers approach or exceed preset values, either via alert dialogs, Growl, or Mountain Lion’s notifications.

-

Offer bandwidth throttling controls that could apply globally, or just to specific applications.

-

Let you create and switch between profiles that either automatically (as with Sidekick and Control Plane) or manually (as with Little Snitch 3, noted above) change the throttling controls to match a location, or any time you’re not in a particular location.

-

Provide a central kill switch for blocking all incoming and outgoing network connections without having to resort to the Network preference pane or turning off the AirPort adapter.

-

Automatically test the current connection to be able to report on the available bandwidth and potentially throttle apps dynamically in response to network conditions. (This is a more advanced feature, but would be welcome.)

We’re happy to talk more with anyone who’s interested in writing such a utility, but in the meantime, developers of network-intensive applications should give more thought to notifying users of significant bandwidth use, providing throttling capabilities, and — at minimum — making it easy to pause and resume the software. Without such awareness and control, it’s all too easy for a small number of users to ruin shared public bandwidth for many others, and even for individuals with tethered computers on mobile broadband to suffer from lousy network performance.

I would like: choose unlimited/medium/light/no bandwidth usage, based current Ethernet network (subnet/router) or AirPort network.

At home & work I would have it unlimited; in other places I would block things like OS updates > 50mbytes.

Applications could tie into this (perhaps in 10.9?), and it would also be nice for blocking insecure services over untrusted networks.

A simpler option would just be to manually specify that you're bandwidth-constrained, and then not auto-download Software Updates, App Store updates (both), or prepurchased TV shows/movies (iTunes season passes).

The traffic reporting tools in the article measure a single computer. For example, Little Snitch will show traffic from the Mac it is installed on. (Rubbernet is an exception within limits.)

But you really want to see the big picture: what total traffic is going through the router? This would show all the devices, including multiple computers, iDevices, consumer electronics, neighbors piggy-backing on open WiFi...

If you have an Apple router you need a tool that can query it using SNMP.

The downside is that type of report shows the address and ports, but not the application that is making the connections.

The ideal solution would be a hybrid: collect data from the router and any individual devices possible.

I'm not talking in this article about home or office broadband, but rather situations in which you have a low throughput or a fixed, low limit. Thus, a per-computer measurement is all that's needed.

The issues involved in measuring a home or office network's overall bandwidth use, the caps there (on some networks, not on others), and so forth has a somewhat different complexion.

I use MenuMeters from Raging Menace to visually monitor my network utilisation. (It only gives the overall network view, but it's waaay better than nothing at all.) My home broadband connection is quite slow and might more correctly be called narrowband, so it's sometimes handy to note why it's currently being saturated or if that the big download has now completed.

However, I sometimes see unexpected activity saturating the connection, so I immediately want to know what app is behind it? Is it some sneaky malware? Or is it just, say, my antivirus software puling another update? (I've now learned what to immediately check for that.) Or is it Photo Stream pulling the iPhone snaps I took earlier in the day from iCloud? (That's harder to positively confirm, though I've also learned the circumstances under which that will happen - usually just after login.)

In short, I mainly want to use per-app monitoring for security purposes... I'll certainly take a look at Rubbernet - thanks.

Self regulation is an intelligent person's response to the problem, but sadly one that doesn't help with lots of clueless (or piggy) users sharing a hotel or Amtrak connection. Shared network routers will need to implement per-user throttling to really address the community problem.

These techniques are valuable for cases where you are your own worst enemy.

I would argue you may miss the point of this article, which is that many elements of your system automatically transfer large amounts of data without your explicit knowledge, nor is there any good way to control many of them.

If I leave one of several things on my system turned "on" (i.e., in default configuration) before hitting Amtrak, am I piggy when one tries to download 1 GB? I don't think I am.

That feels like blaming the user for a situation that the operating system's maker could be involved in addressing.

That's a separate issue from someone trying purposely to download large files or streaming HD video in a setting in which that's inappropriate because of shared use.

Glenn, You're missing part of the equation: The router needs to be able to report on its capabilities and the capabilities of the internet connection behind it.

I can see this taking many forms, but the simplest would be for the server to have a very small http server on it that serves a bandwidth.xml file, which tells each client about the connection. A hotel could configure a static bandwidth.xml file to tell the client no backups from 5 pm until 11 pm, so a majority of the capacity can be used for people watching movies, or something.

I can see more complicated implementations as well, but relying on a client to suss out the internet speed on a shared connection is a bad idea, since there is no way to reliably obtain this information. Speedtests don't do it, because they measure the available bandwidth, so if someone was already downloading a file that will be excluded..

That's unlikely to happen, though I agree it's a good idea. For that to happen, you need revision in multiple operating systems, software, and routers. Too many different firms and moving parts.

And this is different from any other standard on the internet how? Put Dropbox, Crashplan, Microsoft, Google, Cisco, Netgear, and a few others in the room, and have em hammer it out. That is after they figure out which room is big enough to hold all of those companies..

A low-bandwidth situation that is likely to become more common is in-flight wifi. On one intercontinental flight recently, it cost $5 for 30MB of satellite traffic. Exceeding this cost something like 15c/MB. So I definitely do not want automatic downloads happening!

I live in Canada, where internet accounts have a monthly cap, with extra charge for more usage. It would be nice if there were a way to monitor usage on a local network (several computers, plus maybe a thief?) to figure out who/what is responsible for unexpected usage. This could be a fairly rough monitor, say usage by one-hour blocks and by each computer.

I live in a rural area and would be interested in an article about dealing with bandwidth issues there. I had been a HughesNet customer for several years, but recently switched to Wild Blue Exceed. I have been disappointed in Exceed's speed and reliability and now wish I weren't stuck in a two year contract.

I live in a remote location where my only choice for broadband is satellite or cellular. I found satellite to be unacceptable because of latency and data caps. My cellular currently doesn't have a cap but Verizon is forcing me to go to a capped plan. I'm a Mac user with a household of 3 computers, 3 smartphones, an iPad, DVD player and gaming system that according all requiring frequent application updates along with normal usage (we view very few movies). It would be nice if developers just updated the software that changes rather than the whole application it would help all of us on a bandwidth budget because there is no easy way to control a home network.

Thanks, Glenn, for this excellent piece, which reads like a collection of oft-revisited chapters in the story of of my peripatetic digital life.

It seems apt that I'm writing this from the remote village in northern Thailand where my family and I have spent a third of each of the last twenty years, and where I received this article via my plain-text e-mail subscription to TidBITS on a tethered iPhone GPRS connection that today was peaking out at less than 2 kbps.

Slow as it is, this could actually be called progress, since as recently as a decade ago checking e-mail from here required a 40 km drive to town, followed by pocket-knife and alligator-clip access to some kind soul's land line, and then paying that person's long-distance charges for time used to the nearest ISP in Bangkok. It's fair to say that in those days we rarely indulged in much Web surfing, and were grateful for offline e-mail clients like BulkRate and Eudora.

Times have changed. Now when we drive to town we can log onto WiFi from any number of places at a pretty god clip, and four hours north in Chiang Mai I can connect this same iPhone to any of several 3G networks, all of which are significantly faster than what we get today from Verizon in Santa Barbara. And it's not expensive here either. No-contract, pay as you go, unlimited monthly Internet access (for GPRS, EDGE, and/or 3G) is only 750 baht, currently about US$24 per month. It's just that 3G is available only in a few urban areas, whereas our home is well out in the glorious boonies where GPRS is the only option.

My point, though, is that I love it here, and thoroughly enjoy these extended periods off the main grid, so I think your point is very well taken that disconnecting or throttling down should be as simple and transparent as changing time zones.

The trouble now is that the only convenient, and for at least one service (iCloud) the only safe, way to disconnect is to leave the computer off. That seems unreasonable, as I'm sure I'm not the only one who would happily go weeks or even months at a time without a Web browser as long as I can send and receive e-mails without having to drive anywhere to log on.

As you point out, most services include straightforward tools for this, so it seems unconscionable that iCloud does not -- even in its ostensibly less inchoate Mountain Lion incarnation. The solution? Me, I've simply opted to never turn iCloud ON until this and other peripheral issues* are fully resolved. For sharing BusyCal and the like I can easily establish a fully functional LAN wherever my collaborators and I happen to be, and for real-time remote sharing Google Calendars have always worked just fine, either with or without BusyCal.

On other fronts, your list includes all of the tricks I've learned, and as soon as I get a chance to download it I will give Rubbernet a whirl. Instead of that I've been using two not mentioned in your list: NetMonitor and NetMonitor Sidekick, both by Guy Meyer. The combo gives very detailed info as to which ip's are using bandwidth, and, in addition to a handy menubar meter, will output detailed reports which can be very helpful in precisely identifying bandwidth hogs in apps, daemons, and web sites. Unfortunately, Mr. Meyer's web site http://homepage.mac.com/rominar/net.html is gone and maybe he is too? Hard to tell from this connection, so if anyone has any clues ...

One footnote about CrashPlan, particularly in reference to Adam's memory lapse:

To Pause (and Resume) CrashPlan on All Platforms

* Open CrashPlan and double-click on the logo in the upper right.

* A text input area appears at the bottom of the application window.

* In the input area, type: "pause" (no quotes)

* You can specify the number of minutes to pause by entering pause n, where “n” (no quotes) is the number of minutes to pause. If you do not specify a time period, CrashPlan pauses for 60 minutes.

* Press Enter.

I've used this method many times, often for extended periods, and it has always worked reliably well. For example, to completely suspend CrashPlan activity for 100 days -- with confidence that it will remember to restart itself on day 101 -- you would simply enter enter "pause 144000" since 144000 = 100 days * 24 hrs * 60 minutes. If you come home early, or find yourself with a broadband connection at some point during your trip, then:

* Open CrashPlan and double-click on the logo in the upper right to open the input area.

* In the input area, type: "resume" (no quotes)

* Press Enter.

http://support.crashplan.com/doku.php/how_to/pause_crashplan?s%5B%5D=pause

* Problem Solving | 22 Jul 2012

iCloudy with a Chance of Intermittence

http://tidbits.com/article/13137

* Networking | 02 May 2012

Apple ID Horror Story

http://tidbits.com/article/12977

Re Net Monitor & Net Monitor sidekick ...

On Friday, July 27, 2012, Guy Meyer wrote:

The web site is available at

http://netmonitor.s3-website-us-east-1.amazonaws.com/

I am working on Mountain Lion compatibility

I wish I had a solution to identify bandwidth usage by iPhone app. Our family iPhones have very low GSM data limits (200 Mbytes per month), because most of the time, they are connected to WiFi networks. Sometimes we will get an email notice from AT&T saying that we are approaching the 200 Mbyte GSM data limit on one of the phones. There is no way to determine which app or activity could have suddenly consumed the data.

I would like to see an app that can monitor GSM data for user-configurable bandwidth usage over a set time interval that could trigger a warning. The app could pop up a notification saying, "Warning: You have used 20 Mbytes of GSM data in less than 2 hours." (... or however the user configures the warning settings.)

Check out DataMan. I'm testing it and although it's not perfect (not through its fault, I suspect, but iOS limitations), it will give you usage warnings when you exceed certain amounts per day, week, and month. Plus, you can see usage by app and location.

http://itunes.apple.com/us/app/dataman-real-time-data-usage/id404513413?mt=8

I've played with that too, as even though our contract here in Thailand is for unlimited bandwidth I'm still curious to record the "mileage."

DataMan seems to get the numbers right, and remembers them too, as long as I don't forget to open DataMan before and after each time I restart my iPhone.

Restarting is not something I ever think about in Santa Barbara, but with this ridiculous connection here (currently at 130 Bytes -- not KiloBytes or even Kilobits -- per second) sometimes restarting helps.

Just saw this app - Radio Silence - which might offer a decent interface to shutting down particular bandwidth offenders while traveling.

http://www.macworld.com/article/1168097/

>> ... how to deal with permanently low-bandwidth scenarios ... If there’s interest, we’ll look into a separate article about that topic in the future.)

Yes please. I'm doing forest fire restoration beyond cell phone reach, and if I want anything Internet it's either ham radio or satellite phone. (Irony: the old analog cell system did connect just fine -- the new digital cell towers each have a timing measurement and if your handheld is too far away they ignore it on the assumption some other tower _must_ be closer. And none of them are close enough. It's a speed of light problem.