The Birth of the Ebook

We had trouble finding the door.

It was a late spring day in 1990. Professor Richard A. Lanham of UCLA and I stared up at the ocean-facing building’s decaying balconies and rusted ironwork. Sand swirled at our feet. “I think it’s down here,” I said, looking down a shadowy walkway that led away from the beachfront path with its distant rumble of heavy surf and out to the Pacific Coast Highway with its deafening roar of heavy traffic. Midway along the building’s side we found a determinedly unprepossessing door. We stopped. I shrugged and pressed the buzzer by the door. Several long moments later, it opened. We had found the Voyager Company.

Voyager had invited Lanham to attend a one-day meeting about computers and text, and Lanham asked me to tag along. Lanham was something of a big name in the nascent field of computers and text: a few years earlier, he had completely revamped UCLA’s composition courses, and his new Writing Programs introduced computer technology to undergraduate writing instruction. (Yes, “Writing Programs” is plural; the organization that Lanham established managed several different writing programs.)

I was his technical advisor, anointed with the bizarre payroll title of producer/director. He hired me because my computer program, Homer — which I had begun developing while still in graduate school — had evolved into one of the computer tools used in the Writing Programs classes. Although both he and I had largely moved on from the Writing Programs by then, we had stayed in touch, and it felt right that I would reprise my tech advisor role.

Meanwhile, Voyager, known for its Criterion Collection laserdiscs, had just made big waves in the tiny digital media world when it released its groundbreaking CD-Companion to Beethoven’s 9th Symphony. The Companion, authored by UCLA Professor Robert Winter, married a HyperCard stack to an audio CD recording of the symphony. Designed to run on those few Macs that had CD-ROM drives, it offered all sorts of interactive historical, musicological, and biographical information about the work and

its composer, and even included a running text commentary synced to the CD recording.

Voyager’s president, Bob Stein, had obtained some grant money to explore whether anything comparable to a CD-Companion could be created for literature, and the grant paid to bring several digital text luminaries to Voyager’s Santa Monica beachfront offices to hash out the possibilities. Lanham and I were among the cheap invites: UCLA lay just a few miles inland, so in our case Stein only had to pay our parking and give us a free lunch.

Neither Lanham nor I recall many details about that Bloomsday meeting. He mostly remembers the outré attire — to him — of the Voyager staff. I remember that at least one dog roamed free through the ramshackle offices: we were warned to watch where we stepped. I also recall a long discursive conversation that eventually crystallized into two factions with two distinct visions of the future of digital text. One group proclaimed that text’s future was full-on hypertextuality and the long-awaited death of linearity; the other group saw a future of the Book Renewed, revitalized by all the adornments that digital technology could provide.

Stein (and Lanham and I) fell into the Book Renewed camp. We all agreed that simply putting an ordinary book on the screen was a non-starter — digital text would have to be interactive in some way because the physical experience of reading on even the best desktop computer monitors of that era was less than delightful.

At the end of the meeting, Stein offered me a job. I thought he was joking. Eight months later I found myself being interviewed by Jane Wheeler, who managed the programmers, producers, and artists at Voyager.

Stein had decided that a CD-Companion-like treatment of a Shakespeare play would be perfect for cracking the nut of digital text, and, of the plays, one of the big four — Hamlet, Othello, King Lear, and Macbeth — would make the loudest crack. Of those, he picked Macbeth: among its other benefits, it was the shortest of the four. (Slightly more than 2,100 lines in most editions; by comparison, Hamlet has almost twice as many.) My job was to produce this digital book.

The Expanded Books Project — The first couple of months I continued to work part-time at my UCLA job while sketching out rough ideas for the Macbeth Companion. By summer I had a lot of false starts behind me. Then one day I showed up at Voyager and found everyone buzzing about a review unit of the as-yet unreleased PowerBook 100 that Apple had loaned Voyager. The sleek (5.1 pounds or 2.3 kg!), powerful (2 MB of RAM!), portable Mac with its amazingly spacious screen (640 by 400 pixels!) was passed lovingly from hand to hand.

Florian Brody, a loquacious Austrian with a background in computer science, film, and linguistics, had put a couple of pages of “The Sheltering Sky” on the PowerBook, turned it on its side, and asserted, “This looks like a book!” You could almost see cartoon lightbulbs flaring over people’s heads.

Within weeks, the Macbeth Companion was put on hold and I began working full-time at Voyager on the quickly coalescing book project. In the hallway outside of Wheeler’s office, meeting after meeting took place, or perhaps it was one long meeting that ran for days, ensnaring anyone — artists, coders, even the receptionist — who happened by.

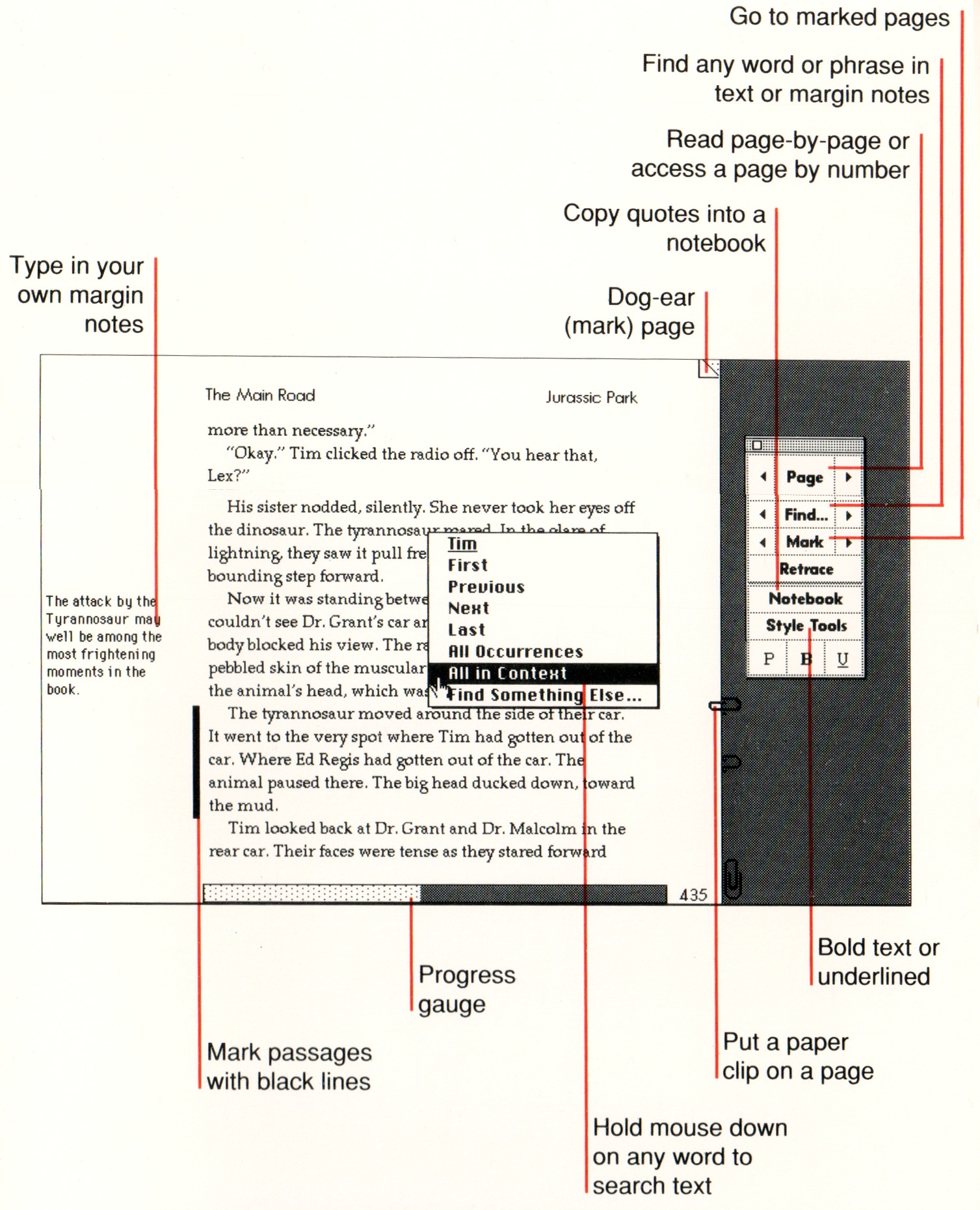

We hashed out the details of what kind of digital book we could make, how it would look, what features it would have, even what the format would be called. It was inevitable that the general term would be “e-book,” but we argued for days about what the “e” stood for before we decided that it stood for “expanded.” Many of the standard features of today’s ebooks, including bookmarks, margin notes, and page gauge, first saw the light of day in that hallway.

We built the books on top of Apple’s HyperCard, Voyager’s platform of choice. Colin Holgate, a soft-spoken, compact Brit with an unparalleled talent for making HyperCard do astonishing things, took on scripting the book shell (that is, the empty HyperCard stack into which the book’s contents would be “flowed”). Voyager’s small art department provided a clean,

book-like page design. I laid out the text, using utility scripts that Holgate created to “flow” a book’s text into consecutive pages. As the number of scripts multiplied, I also created a hidden Magic button in the book shell that presented an ever-growing menu of Colin’s scripts (and some of my own) so I could readily invoke them at need. (When I eventually got around to Macbeth, I gave it its own, much more complex Magic button — it may still be there in some early releases of the CD-ROM if you know where to look.)

The first three Expanded Books slowly came into being that fall in a small office by the stairwell on Voyager’s second floor. Copies of the in-progress EBs (as we called them) were regularly loaded on the PowerBook, which Stein had begun to travel with. One day, he returned from a business trip to inform us all smugly that he was the first person in history to have read an EB in the restroom of a jetliner in flight.

By the time the San Francisco Macworld Expo rolled around in January 1992, the first three EBs were ready. They were loaded on floppy disks and packaged in stunning paperback-like packaging designed by Voyager artists. We made it just barely in time: even two days before the show, Stein still wanted to make major changes to the EB interface, but I was ready to get back to work on Macbeth.

The Toolkit and Other Distractions — The EBs were a big hit at Macworld. I spent hours at the Voyager booth, demoing them to hundreds of people, including one very tall, very genial fellow with a plummy BBC accent who turned out to be Douglas Adams; his collected “Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy” novels were one of the EBs. I told him about Macbeth; he suggested I follow it up with something by Chaucer and recommended a book about “The Knyghtes Tale” by a friend of his, Terry Jones. (Yes, that Terry Jones. The book is “Chaucer’s Knight: The Portrait of a Medieval Mercenary.”

It’s both readable and scholarly; I highly recommend it.)

But I couldn’t return to Macbeth after the Expo. Stein had promised that Voyager would produce an EB toolkit so other publishers could adopt the format, and work on that project ramped up almost immediately. Voyager programmers Brock LaPorte and Steve Riggins were drafted to write external C routines for the Toolkit to provide capabilities beyond what HyperCard, even with Holgate’s clever scripts and my Magic button, could manage on its own.

I wrote the Toolkit manual and the book-building tutorial. The example text I passive-aggressively chose for that was Chapter 94 of “Moby-Dick,” the “sperm-squeezing” chapter, much to Stein’s amusement and the embarrassment of almost everyone else at Voyager.

At the same time, I was assigned to do post-production work on a CD-ROM version of Adams’s book about endangered species, “Last Chance to See.” Macbeth languished that spring and summer, wandering in Birnam Wood.

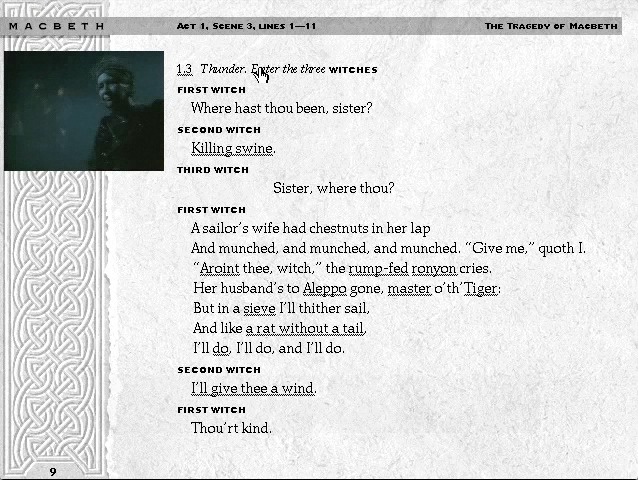

Back to the Highlands — We finished the Expanded Book Toolkit in time for the Boston Macworld Expo that August, and at last I could return to the Scottish play. In the interim, I realized that Macbeth would not be a CD-Companion but, rather, an example of the next stage of the Expanded Book. (In fact, even as I was finishing Macbeth I was also adapting its HyperCard shell so it could be used in other projects. One such was a Voyager CD-ROM edition of the film “Salt of the Earth.”)

Voyager finally assigned some resources to the project. Chief among them was Brian Speight, a graphic artist at Voyager who created beautifully elegant Celtic-interlace page backgrounds for the program along with maps of Shakespeare’s London and Macbeth’s Scotland.

Stein had already contracted with UCLA professors to write the text: David Rodes, who had wildly popular undergraduate Shakespeare courses, in part due to his own élan as a presenter, and in part to his habit of inviting professional actors, some of them his friends, to perform scenes in class. Rodes wanted more scholarly depth on the bench for Macbeth, and suggested Al

Braunmuller, also a popular classroom teacher, then editing Macbeth for a new Cambridge edition of the play. Braunmuller agreed to produce original essays for the project and to provide an authoritative play text.

Rodes, Braunmuller, and I agreed on a table of contents for the disc; Braunmuller began delivering both play text and essays; Rodes wrote an introductory essay along with act and scene headnotes; and we started to acquire copyright permissions for the picture gallery that would be included.

We still hadn’t picked a performance to sync with the text. I viewed every video production of the play I could lay hands on — the most laughably idiosyncratic starred the otherwise fine actor Jeremy Brett — but we eventually chose Rode’s original pick, a Royal Shakespeare Company performance directed by Trevor Nunn, starring Ian McKellen and Judi Dench.

Voyager video specialists began digitizing a master videotape of it we obtained into 160 by 120 resolution QuickTime video — tiny but watchable; anything larger would take up more space than a CD-ROM could store. They also digitized scenes from three movie adaptations to complement the main performance: Roman Polanski’s and Orson Welles’ versions, along with Akira Kurosawa’s “Throne of Blood.”

Our plan also included a game: a “Macbeth Karaoke” that would enable readers to perform some scenes opposite professional actors. We recorded these karaoke audio tracks in Rodes’s house in the hills above West Los Angeles, with me perched on the daybed in Rodes’s study, digital audio recorder on my lap, while two actor friends of Rodes did take after take of several scenes between Lord and Lady Macbeth, pausing whenever airplanes flew over.

By winter’s end, Macbeth had three complete scenes, including two levels of annotations, and enough accompanying material to be demoed at the open house evenings that Voyager regularly held. Psychedelic explorer Timothy Leary was a guest at one such open house: he repeatedly insisted to me that we had met before (we hadn’t — not, at least, on this astral plane).

When Macworld Expo in Boston rolled around again that summer, I gave the ultimate demo: a performance of the Macbeth Karaoke before thousands of people, staged in the big tent used for the Expo keynote. It was well-received, though neither Broadway nor Hollywood came knocking at my door.

A Walking Shadow — Actors will tell you that Macbeth is a bad luck play, one whose very title you utter at your peril.

We had already been mildly hit by the curse once. In David Rodes’s introduction to the play, he mentioned that the title character in the film “Ghost” was on his way home from a performance of Macbeth when he was murdered. We wanted to illustrate that part of the introduction with a picture of the newspaper advertisement for the movie, but the cost of procuring rights to use the ad were too high.

Now, though, the curse came into full play.

First, at the post-Macworld Expo dinner, Stein crushed everyone’s celebratory mood with an after-dinner speech full of gloom and portents — despite our Expo success, Voyager was facing hard times, and we would all have to work much harder than ever before to make it through them. A few weeks later we discovered that the Santa Monica offices were to close and the company would relocate to New York City at the end of the year, ostensibly to be closer to the center of the publishing industry.

I was encouraged to uproot stakes and move to New York, but, with all my family and friends in Southern California, I elected to stay and finish the CD-ROM in Santa Monica, working remotely with Voyager via modem and phone from my apartment. In February, the 1994 Northridge earthquake struck, destroying the old Voyager beachfront building, and nearly wrecking my home office — it took almost a week to get the office in working order again.

The big blow, though, was when Stein informed me that rights negotiations with the Royal Shakespeare Company had hit a snag: they wouldn’t approve the use of the video unless we made it much larger, a technical impossibility at that time. As a sop, the RSC did, however, grant us audio rights to the performance. I rewrote the text-synchronizing code so that it would work with an audio-only track. Given all the material we had to leave out of the CD-ROM in order to accommodate the complete video, this development, so late in production, was heart-breaking.

At about the same time, Stein informed me that I would really need to live in New York to contribute to future Voyager projects: he did not think it was feasible to maintain a remote West Coast office with a single employee.

So it was that, two weeks shy of the four-year anniversary of that first meeting in Santa Monica, and with the CD-ROM all but finished except for final QA testing, I emailed Stein my resignation.

This time, I had no trouble finding the door.

(This article originally appeared in slightly different form in issue 32 of The Magazine, 19 December 2013. Used with permission.)

To add to Michael's memory of events: When Voyager were loaned the future PowerBook 100, it had not yet been given a name. As for the Expanded Books name itself, that was very much a code name, good for the teeshirts that they made, but as the publishing day got closer we had heated debates about what the real name should be.

My vote was to keep the code name, because, as Michael suggested, I felt sure that the generic term for such things would become e-books, and being expanded-books would fit the generic term better.

One other favored contender was Power Books. Then, literally while in a meeting talking about what to call the EBs, we heard what name Apple had chosen for the machine.

That helped settle things!

It did indeed! ?

(Hi, Colin!!)