Why I Switched from Gmail to FastMail

Ever since I was invited to the Gmail beta over a decade ago, I remained faithful to Google’s email service. Before that, I had bounced between email accounts, never keeping one for more than a few years. With Gmail, I finally had a stable, trustworthy place to store my messages, and it was completely free.

But over the past few years, cracks developed in my relationship with Gmail, as Google and Apple’s relations fractured. It began in late 2012, when Google axed Google Sync (see “Google Drops Google Sync for Most iOS Users,” 18 December 2012), which meant that Gmail would no longer “push” messages to Apple’s built-in Mail app for iOS. Google retained Google Sync on devices that already had it configured, but you were out of luck when you purchased a new one — making Google Sync a dead end. If you want push email with Gmail on iOS, you now have to use Google’s own Gmail app, which doesn’t always mesh well with iOS, or subscribe to Google Apps for Work, starting at $5 per

month, though that doesn’t integrate well with personal Google accounts.

The cracks widened the next year, as Joe Kissell wrote of his rage-inducing incongruties between Gmail and Mail in OS X 10.9 Mavericks (see “Mail in Mavericks Changes the Gmail Equation,” 22 October 2013). While Apple had tried to make Mail and Gmail work better together, its efforts caused problems for those who had previously taken matters into their own hands, as described in Joe’s “Achieving Email Bliss with IMAP, Gmail, and Apple Mail” (2 May 2009).

For many Apple-inclined Gmail users, it was a tipping point. It seemed as though Apple Mail would never work properly with Google’s non-standard IMAP implementation. Joe decided to kiss Gmail goodbye, while others, such as blogger and author David Sparks went all-in on Gmail. Adam and Tonya Engst are in the latter camp, using Mailplane to integrate the Gmail Web interface with the Mac, see “Zen and the Art of Gmail, Part 4: Mailplane,” 16 March 2011.)

The conclusion that many of these folks came to is that Gmail was designed to be Web-first, with support for “legacy” email protocols like IMAP and POP3 added as an afterthought. You’ll never get the full benefit of Gmail with a traditional email client, and even under the best of circumstances the two just often don’t work well together.

Even though Apple has fixed many of the Gmail issues that plagued Mavericks, Mail’s support for Google’s IMAP implementation still left much to be desired. Sometimes the sync would get stuck, requiring me to restart Mail, but most of the time it was just slow, delivering messages to Mail minutes after they had arrived on the server.

My fears were compounded by Google’s behavior since founder Larry Page took the helm as Google’s CEO. Under Page, Google has axed many ancillary services, such as Google Reader (see “Explore Alternatives to Google Reader,” 18 March 2013). While I don’t think Gmail in general is in any danger, some are wondering if Gmail’s IMAP support might end up on the chopping block.

Speculation about industry changes aside, there is something disconcerting about being at the mercy of a company for an essential service like email (as Adam Engst pointed out in “A Not So Short List of People to Blame for Internet Content Woes,” 16 October 2015, most of us don’t pay for online services, which has led to adverse consequences). But even more important than the service itself is your email address. If you own the domain that your email address is attached to, you can move that to almost any service you wish. But if you’re stuck with an aol.com or gmail.com address, those addresses are tied to

the companies that own them, and if one day they decide to drop those services, you’ll be scrambling to fix not only your email, but all of the accounts tied to that address. Granted, I doubt that day is coming anytime soon, but I decided that having more ownership of my email would bring me piece of mind.

Why FastMail? — Since my goal was greater control over my email, why didn’t I just host it myself? Because although the basics of running a mail server aren’t that difficult, the environment is, to quote Charles Edge in “Take Control of OS X Server,” a toxic hellstew. What with constantly fighting off spammers and bots and zombies, running a mail server isn’t something nearly anyone among even my most technically minded friends will attempt any more. It’s a full-time job best left for experts.

Given that I wasn’t going to do it myself, why did I choose FastMail over the many other email providers?

Since I’m an Apple guy, why not use iCloud Mail? It’s tempting, because setup is dead-simple, it offers push email, and it would soak up some of the unused iCloud storage space I already pay for. Unfortunately, iCloud doesn’t support receiving mail at custom domains, so I couldn’t use it to receive email at my tidbits.com email address or at my own personal domain. Also, Apple’s spam filter often annihilates messages with keywords it doesn’t like without even dropping them into a spam folder. Besides, I already have a lot of things tied up in iCloud, and I prefer not have all my eggs in one basket.

Which brings me to FastMail, which has a lot to like. For one, it’s has staying power. The company was founded in 1999, making it even older than Gmail. And although it was briefly owned by Opera Software, it is once again independent and privately held.

FastMail is dedicated to email. Sure, it offers some side dishes like contact and calendar and contact syncing, but they exist to support the email service. I don’t anticipate FastMail launching a maps service, a search engine, or a car. FastMail is focused on offering the best email service it can, and since it’s not a public firm, it’s free to do so without worrying about what Wall Street thinks.

But every service has its high and low points. After using FastMail for a few months, here are my impressions.

FastMail Features and Benefits — FastMail is a commercial service, but it’s dirt cheap for something I rely on every hour of every day. I pay $40 per year — less than $3.50 per month — for the Enhanced tier, which offers 15 GB of mail storage. A 30-day free trial is available so you can test the waters.

I availed myself of the trial, and was impressed with how responsive the FastMail team is, and not just for direct questions. I moaned about a few things on Twitter, and they sought me out to discuss my concerns. I like that if something goes wrong, or if I don’t like something, I can email someone at FastMail and know that my complaint will be addressed, or at the very least, heard.

But the killer feature for iOS users is push email support in Apple’s iOS Mail app. As far as I know, FastMail is the only email provider outside of Apple to offer this. I don’t have to use a third party app on my iPhone, and I no longer have to wait 15 minutes (or longer) to get new messages on my phone.

Even in the Mac’s Mail app, where Gmail offers push email, I’ve found FastMail’s IMAP sync to be quicker and more reliable. I rarely have to restart Mail to fix syncing with FastMail, unlike Gmail, and because FastMail’s IMAP implementation is completely standard, it’s likely that Mail won’t suffer from odd complications as it does with Gmail.

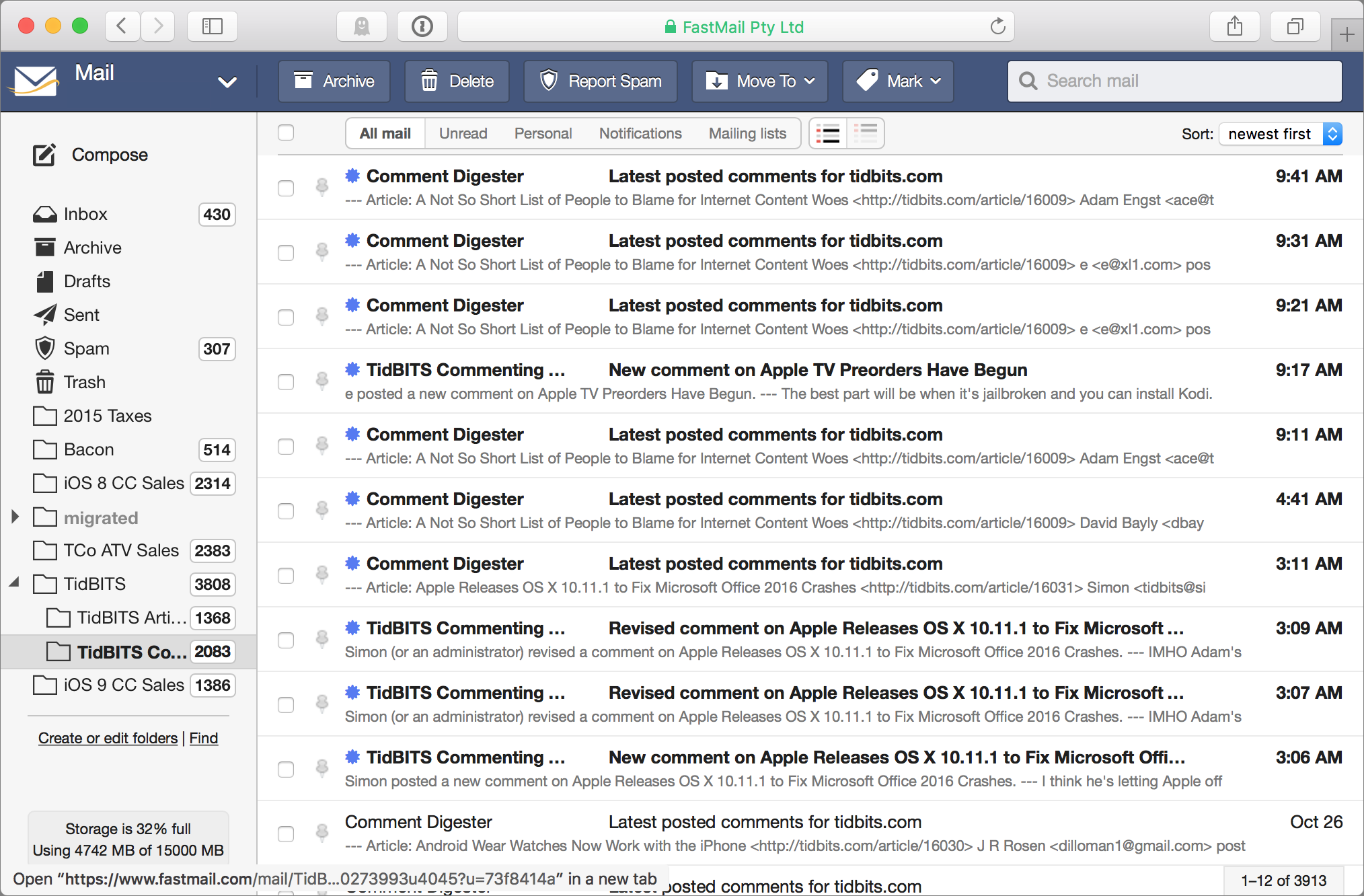

While FastMail’s IMAP support shines, the Web interface is nice as well, with a crisp, ad-free design. In fact, I find the mobile Web version of FastMail to be better than Gmail’s mobile Web app, as it supports swipe gestures for managing email. Fastmail also offers an iOS app, but I find FastMail’s Web app to be so good that I don’t need it.

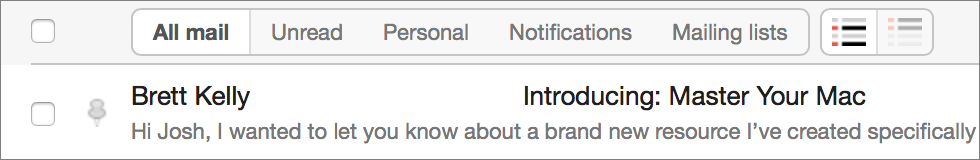

Interestingly, FastMail’s Web interface offers views for all mail, unread, personal mail, notifications, and mailing lists, letting you quickly filter your inbox. It’s similar to Gmail’s multiple inboxes, except it doesn’t actually split your email into multiple inboxes.

Unlike iCloud, FastMail supports custom domains, and offers two options for setting them up. You can either configure the appropriate MX records with your domain name registrar, or you can set your nameservers to FastMail’s and let them do the work for you. In this latter scenario, if you have a Web site tied to your domain name, FastMail offers a tool to forward DNS lookups appropriately. I decided to route everything through my registrar, which provides more control and wasn’t difficult to set up.

When it comes to aliases and managing multiple email addresses, FastMail offers a smorgasbord of options. There are Virtual Domains, which let you set up various email addresses at your linked custom domains, so you can have [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], etc. There are aliases, which let you create any number of alternative email addresses, which can be handy for maintaining your privacy and avoiding spam. For instance, I could create an alias called [email protected], and email sent to that address would show up in my inbox. FastMail owns a lot of domains, like sent.com, bestmail.us, speedymail.org, and so on, so you have a lot of options there. And finally, you can create what FastMail calls

personalities. These are like aliases that you can send mail from. For instance, if your old email account is [email protected], you can set up FastMail’s Web interface so you can still send mail from that address.

You may wonder how FastMail’s search stacks up to Gmail’s. Pretty well, actually, with a similar search syntax, though I usually use Mail’s search instead (which has become pretty good itself with iOS 9 and OS X 10.11 El Capitan).

However, I find FastMail’s server-side filters, called rules, to be a wash in comparison with Gmail’s. FastMail’s rules support advanced capabilities like regular expressions and even sieve scripts that are missing in Gmail, but unlike in Gmail, you can’t see a preview of the messages that will be matched or apply them to existing messages.

In term of performance, FastMail lives up to its name, it has proven itself reliable in my testing, and I’ve found pleasant to use overall, with as many features and configuration options as you could want. But that flexibility might also be its biggest drawback.

The Bad — I haven’t found anything I would call “bad” about FastMail, but it’s definitely skewed toward power users. If you’re a casual user, FastMail’s many options might be overwhelming. Sure, you could sign up, and use a fastmail.com email address in conjunction with the Web interface and iOS app, but you wouldn’t be getting your money’s worth.

Perhaps my biggest hesitation when testing FastMail was its funky two-factor authentication (2FA) system. As you’ll recall, 2FA depends on not just a username and password, but also a randomly generated number, usually accessible from your iPhone. The way that 2FA works with most services is that you enable it, and then enter that code along with your password.

FastMail handles 2FA differently. You create a master password that has full access to your account and doesn’t require 2FA. Then you create a secondary password with 2FA protection and either log in with that or with app-specific passwords, which you can also create for email clients that don’t support 2FA.

The concern with this approach is that leaving the master password unprotected by 2FA would create a vulnerability, but as Security Editor Rich Mogull explained to me, the key is to create a strong master password, store it securely, and use it only if absolutely necessary.

Another issue with FastMail’s 2FA system is that it doesn’t play nice with 1Password when logging in to the Web client. Pressing Command-\ on the keyboard has 1Password insert your login info and proceed with the login, but that throws an error, since you must first click More and enter your 2FA code. With most services, after you enter your username and password, you’re then presented with a secondary screen that prompts for your 2FA code.

I’ve raised these concerns with FastMail and have been told that the company is working on implementing a more “normal” 2FA system.

Many people told me beforehand that FastMail’s spam filtering isn’t as good as Gmail’s. After struggling with it for a bit, I’ve found that isn’t quite true, but it isn’t as automatic as Gmail’s spam filtering.

Like everything else with FastMail, there are a lot of options. You can set FastMail to scan for viruses and automatically discard virus-laden email messages. Then there are different levels of spam filtering: basic — which filters known bad hosts and relays — normal, aggressive, and whitelist, the last of which allows only email from a list you specify.

You can also train FastMail’s spam filter. There are buttons for this in the Web interface — Report Spam and Not Spam — but if you’re using IMAP, then you’ll have to set up spam learning folders. Basically, you tell FastMail that the messages in certain folders are either spam or not spam, and FastMail tailors its filter accordingly.

If anything, FastMail’s spam filter was a bit too aggressive for me at first, even on the basic setting, with a lot of false positives, but I’ve finally gotten things working more or less how I want. Here’s how:

- I set FastMail’s spam filter to basic.

- In FastMail’s folder settings, I set the Inbox folder as non-spam and the Spam folder as spam. (Note that Fastmail recommends against setting up the Spam folder as a spam learning folder, as it can cause a feedback loop. However, this seems like the best way to configure it with Apple Mail, and it’s working great so far. You can always choose another folder or folders.)

-

In Apple Mail on the Mac, I enabled junk mail filtering, and configured Mail to move junk mail to the Junk mailbox, which maps to FastMail’s Spam folder.

So far, this is working well, and FastMail and Apple Mail seem to be in agreement about what I consider spam. Another thing I did that helped tremendously is set up a “Bacon” folder. In email jargon, bacn is a relative of spam: something you might have opted into (or failed to opt out of), but don’t necessarily want in your inbox, like marketing emails. The key difference between spam and bacn is that bacn plays by the rules, which means that every email has an unsubscribe link. So, I set up a rule that sends any email containing the word “unsubscribe” to a folder called Bacon, skipping my inbox.

My Bacon folder is a mix of junk and desired email (like issues of TidBITS), but is rarely anything urgent. I made shortcuts to that folder in Mail on Mac and iOS and make a habit out of checking them at least once a day. The net benefit is that my inbox is much more focused on personal correspondence and important email alerts, so I no longer miss important messages among the daily avalanche of press releases and mailing list postings.

Is FastMail for You? — Overall, I’m pleased with my switch from Gmail to FastMail. It offers all the features I want, plus the peace of mind that comes with supporting a company providing a quality service.

However, the transition wasn’t easy. I had to transfer gigabytes of old email from Gmail, set up email forwarding from Gmail to FastMail, alter my domain settings, configure my email clients for FastMail, and manually transfer messages that the migration missed.

Even now, I still need to change the email address associated with dozens of my accounts. And changing the email address associated with my Apple ID caused all of my Apple devices to freak out, requiring me to log out of iTunes, iCloud, and Game Center on all of them and then log back in. Scary, but it worked out, although I got lucky — I later learned that it’s possible to hose an entire Apple account this way.

FastMail made the transition as easy as possible, but it’s a daunting task in any case. It’s definitely something I wouldn’t recommend a casual user to attempt without help.

If you’re dependent on Gmail features like multiple inboxes, the capability to undo sending for 30 seconds, and labels, and you prefer Gmail’s Web interface, you might find FastMail frustrating and backwards.

And if you’re looking at alternatives to Gmail for better privacy, you’re probably wasting your time, unfortunately, since much email ends up going through Google’s servers anyway. However, since FastMail is an Australian company, national security letters do not apply to it, so if a government demanded access to your email, you’d likely hear about it.

If you lean more toward Apple’s mail clients, are frustrated with your current email provider, and want to feel as if you have more control over your email, then I would highly recommend the 30-day trial of FastMail to test it out.

The word I’d use to summarize why I switched to FastMail and stuck to it is control. With my email at a small, focused company, under my own domain, and using standard IMAP protocols, for the first time in long time, I feel as if I have control over it. And as someone who depends on email for a living, the nominal price and the pain of transition were worth it.