iPhone 11 Night Mode Brings Good Things to Light

When it’s dark and you try to capture a picture with your camera, there are only so many photons to go around! Seriously: all photography boils down to light, light to photons, and insufficient photons to bad nighttime pictures.

Apple has made significant headway on this problem in the iPhone 11 and iPhone 11 Pro models with the introduction of Night Mode. The feature relies on the increased sensitivity of the iPhone 11’s wide-angle camera while leveraging computational photography to construct an image far better than would otherwise be possible with the camera’s optical capabilities.

Night Mode is a kind of “dark HDR.” Instead of shooting photos quickly with slightly different exposures and then combining the most expressive tonal ranges of each, Night Mode grabs many images over a longer interval and cleverly interleaves their best parts using a much more complicated set of decisions to produce a nighttime photo without significant pixel noise or blurriness.

Why is it so hard to take pictures in the dark? What has Apple tried so far? And, most importantly, how successful is Night Mode?

Electronic, Photonic

It’s hard for a camera to capture light in the dark because, literally, there isn’t very much of it. While it’s easy to think of light as a sort of suffusion from a source, we know that it’s really a bazillion individual photons, emitted from atoms that have been excited in such a way that shifts their electrons back and forth.

You don’t usually have to deal with the photonic nature of light until it gets dark because film and digital cameras generally take good to great pictures as long as there’s enough light to read by comfortably. With a lot of photons to capture, there’s no shortage and tones—intensities of light—are represented accurately.

In traditional cameras, there are two ways to capture more photons: open the aperture—the circular throttle in the lens—much wider to let more light onto the film than during bright shots, or increase the time the shutter is open to let more photons land on the film, known as the exposure time. The drawback of a longer exposure is that it cannot capture motion well, so fast-moving objects become a blur. High-speed cameras can crisply capture things like a runner crossing the finish line by using extremely short shutter times, but they require a lot of light to produce a clear photo. The calculus is a bit different in phone cameras. (Film cameras also had an ISO/ASA number, which referred to the grain size of the light-receptive crystals: bigger crystals, or a higher ISO/ASA, need less light to capture a tone but resulted in “grainier” photos.)

A digital camera’s sensor (typically a CCD or charge-coupled device) is essentially a photon collector. The sensor is more or less a specialized computer chip. Each pixel on the camera’s sensor acts like a hoop into which photons fall like basketballs. As the photon effectively enters the hoop—striking the sensor—it gives up its energy, producing an electron through the photoelectric effect. The electron is captured by the CCD in a “well,” a sort of bucket that collects them until the exposure period is over. Then the sensor uses that captured collection of electrons to determine the tonal value for the pixel.

(Tone is the only thing that digital camera sensors capture: color images are created by covering individual pixels with a filter of red, green, or blue. Typically there are twice as many green pixels as the other two, as green light best captures the neutral tonal range of a scene best.)

When there’s a lot of light in the scene, a digital camera has to use a short exposure to avoid filling the sensor’s wells so fast that all the detail is blown out. With less light, a longer exposure allows a balanced picture, though it can be blurry if anything in the scene is moving.

However, when it’s downright dark out, few photons strike the sensor at all. Because there’s background noise and the sensor relies on an electrical charge to image the scene, the sensor scoops up errant electrons along with the good ones.

The traditional way of capturing night shots is to increase the exposure time, but that doesn’t work when people are moving, even a little bit. A short exposure either doesn’t capture enough light or requires the camera to boost the ISO so much that it introduces noise—speckles of various colors that were never there.

Imagine a trillion people throwing golf balls from a great height into an ocean of densely packed square baskets. Some balls will fall directly into the basket the thrower was trying for, but others will hit a rim, bounce around, and fall into a different basket. Imagine further that when there are fewer balls to throw, the throwers’ aim is worse, and thus more balls are likely to land in the wrong spot, producing the wrong count—the speckled pixels in a dark photo.

A camera maker has a bunch of variables it can tweak to ameliorate this problem, all of which improve the results across all light conditions. A lens with a larger aperture will let in more light. A sensor with deeper wells can collect more electrons, and it’s possible to give the sensor greater sensitivity so it can distinguish more tones, more accurately, even in the deepest shadows. Bigger pixels in the sensor can also capture more light in the dimmest circumstances.

Over the past few years, Apple has tweaked all these camera variables. It opened the aperture by about 50 percent between the iPhone 6s and iPhone 7 updates, with the primary lens increasing from f/2.2 to f/1.8. (The f/stop measures the aperture’s diameter.) The iPhone X and subsequent models have featured sensors with bigger pixels and deeper wells.

(Paradoxically, increasing a sensor’s area and adding more pixels, instead of making the pixels larger, decreases sensitivity, because less light hits each smaller sensor. That’s why the megapixel count has become so much less important once the entirely adequate 12-megapixel size was reached a few years ago. Since then, all the focus has been on sensitivity and tonal range and discrimination. This works exactly like increasing film grain size to bump up the ISO/ASA speed.)

The wide-angle lens sensors in the iPhone 11 models improve even further. While the sensor size and pixel count remain the same, Apple boosted sensitivity by 33 percent. (Apple also dramatically improved sensitivity in the brightest conditions: the current camera can shoot exposures as short as 1/125,000th of a second, six times faster than the iPhone XS.)

The telephoto lens on the iPhone 11 Pro and iPhone 11 Pro Max can also be used with Night Mode. Apple opened the aperture on that lens from f/2.4 to f/2.0, about 50 percent better, while increasing its sensor’s sensitivity by over 40 percent.

Since the iPhone X, the wide-angle and telephoto lenses have both featured optical image stabilization, a mechanical system that counters small movements and increases the effective f/stop, because it enables longer exposures in the same light. (Optical image stabilization doesn’t help much with motion in the scene, because the actual exposure time remains the same.)

Before Night Mode, Apple had used its lens and sensor improvements to try to make low-light photography reach a minimum level of quality, letting you capture an okay picture a lot of the time instead of a blurry or muddy one. Apple also improved its built-in flash approach over this period, but because the elements can’t be angled and are LED-based, using it is a last resort. The iPhone flash often produces photos that are garish or overbright, but it can make a scene that was previously unphotographable into one you can record.

Night Mode is a quantum improvement over these previous efforts. It’s a sophisticated, multi-prong approach that can produce excellent pictures, not just images of last resort. Apple is not the first company to take this route, as Google and other phone makers have pursued synthesized low-light pictures, but Night Mode ranks with the best of the solutions.

Use Night Mode Effectively

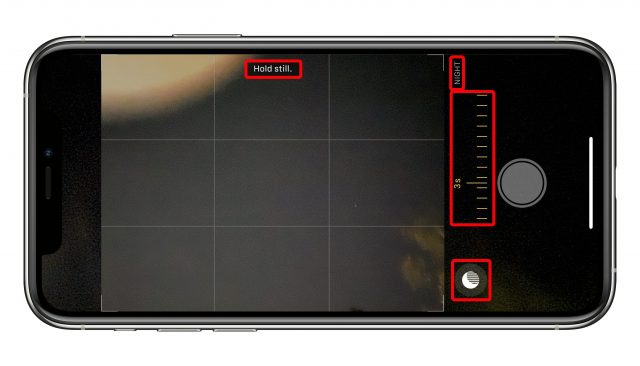

You don’t have to set up Night Mode. In fact, the Camera app always either suggests it or turns it on when it judges that the conditions are right. The Night Mode icon appears at the top left (or bottom left in landscape orientation) of the Camera app. If the app encounters a marginal lighting condition, it suggests Night Mode by showing its icon in white; tap it to turn it on. However, if the Camera app’s analysis reveals that the only way it can take a good photo is with Night Mode, it turns it on and shows its icon in yellow with a duration in seconds.

When you tap the shutter button, try to hold still while the image fades in to full intensity and the timer counts down. If you want to try a longer shot, tap the Night Mode icon to reveal a slider that lets you adjust the amount of time during which a picture is captured. You can also use the slider to swipe to the right all the way to Off if you want to override the Camera app. There’s no way to disable Night Mode as a general option, only on a per-shot basis.

Night Mode doesn’t keep its electronic shutter open for a longer period. Instead, as with HDR, the Camera app collects a series of images over the period of time marked. These images are then combined in a method similar to digital image stabilization in video. (That’s why I refer to the Night Mode’s time of capture as its “duration” instead of “exposure,” because it’s capturing a lot of different actual exposures.)

The Camera app can also detect if you have your iPhone on a tripod, monopod, or in another stable situation by consulting its internal sensors. If so, it might suggest a longer shot. You can adjust the duration to be as long as 28 seconds! (The maximum is a value that Night Mode sets, so you may see a shorter duration at times.)

You can see the effect of multiple exposures over a very long capture clearly in some photos I’ve taken on a tripod at long durations. We live under a flight path in Seattle, so planes often fly over our house in a straight line heading south. Their lights, when shot in Night Mode, can result in artistic blurs. On one clear night when I was testing Night Mode, I also picked up satellites—possibly the International Space Station—that were invisible to my naked eye, but that tracked as blips across each duration that was long enough to show them.

In a briefing, Apple explained that the images captured use “adaptive bracketing,” a technique that captures the same scene multiple times with different settings. Some shots may have short exposures to capture motion, while others are longer to pull detail out of shadow areas. The new iPhone 11 sensor apparently provides Night Mode the quality needed to create these different exposures in the worst lighting conditions.

The Camera app then processes these images using machine learning via the Neural Engine that’s built into the iPhone 11’s A13 Bionic processor. These machine-learning algorithms rely on training, initially by humans, to figure out the most desirable characteristics of an image and then apply them with new and novel inputs. The algorithm knows the kind of appearance, color, and details people prefer from the training, and emphasizes that in constructing a single image from the Night Mode flurry of shots. (The Neural Engine also drives the new Deep Fusion feature, a kind of super HDR, that first appeared in iOS 13.2.)

Apple said that the resulting image is designed to preserve the sense that it’s night—it’s not trying to turn an evening scene into false daylight. That’s why Night Mode has an emphasis on preserving color while boosting brightness. Nonetheless, it’s not always successful. Sometimes, when I shoot a scene that’s quite dark except for some pinpoints of light—in a room, from street lights, or emanating from houses—the resulting photo feels more like dawn than night, and the colors can shift, too.

But the beauty of Night Mode relying so heavily on machine learning is that Apple’s algorithms will keep improving. Plus, we’ll learn what conditions produce optimum results—or use Photos or Lightroom to tweak the results better to our liking.

Regardless, I’ve found that Night Mode has dramatically changed when I even think about taking photos. Previously, the mediocre quality of low-light photos discouraged me sufficiently that I would take pictures only in a pinch or to record a moment. Now, I find myself snapping shots outdoors at night, and at late dinners in dim restaurants. In fact, the novelty of Night Mode may have turned me into a bit of a photographic pest. But like all sufficiently advanced technology that’s indistinguishable from magic, I’m sure I’ll get used to it soon enough.

Glenn,

Thanks for covering night mode thoroughly. Unfortunately it just reinforces that it’s a big disappointment for me.

Apple pitched it as a nearly miraculous solution to what it finally admitted was lame low light performance in its iPhone lineup to date. You called it mediocre, but it has always been pathetic. I have lived in envy of droid owners who came away with bright indoor photos when my iPhones had dark, grainy, blurry results every time.

So imagine my childlike thrill when Apple made this announcement. A huge reason I was willing to walk away from my iPhone 8 Plus telephoto lens to get the iPhone 11.

But then I started reading the online reviews and was crushed when i heard that it relied on an extensive “duration” to get the job done. Then I reread Apple’s info and noticed that the sample pic was of a girl lying on a couch who was probably perfectly still.

And I was dumbfounded by all the big reviewers posting examples of closets and other “still life” as examples of how well this performs. Really?? If you have a still object, you can always use a tripod and even the dead of night will light up if you wait long enough. And that 0.1% of the population will find that night mode speeds things up.

But the 99.9% of the photos I take, my friends take, and I think most of the world wants to take that suffer badly from lousy low light handling is indoor and evening shots with friends: parties, concerts, gatherings. With people. People who are having fun. Who will pause for a moment, if you’re lucky, to take a group shot with drinks in hands between dancing or whatever, but that’s it. You don’t have 3s to work with. You can’t ask people to stay perfectly still. This isn’t the 1920s.

So the results I got are that the people who stay reasonable still come out decent. And those who move a bit too much are blurry.

But here’s the other sinker. When you’re taking low light shots at these parties, it’s extremely likely that you’re going to do so with the selfie camera, which has none of this technology at all.

I will admit that, given the right conditions, Apple has brightened up nighttime photos impressively. But the fact that it doesn’t support the selfie camera and requires your happy subjects to freeze for several seconds means that this has barely addressed the real life use cases.

The tripod and still life crowd can, however, rejoice that they have a much better tool at their disposal.

It’s interesting to read this view “from the other side”… about the Google Pixel 3 and it’s camera.

(Watch the video)

Have you seen the Milky Way with the naked eye? Because that “haze” is not it.

Speaking of using a tripod, years ago I purchased a holder for the iPhone that a tripod screw would fit. Every time I got a new iPhone it would not fit the mount/holder and I had to buy another holder. I had one that gently squeezed some arms apart to fit the phone, but then adjusting the phone’s controls would often cause the phone to slip and the angle to shift up, down or diagonally and it had to be repositioned. First, what’s the best product currently for a tripod mount on iPhone 11 Pro Max with the Apple leather case? And secondly, is there one that is generally future-proof for phone size variations?

Nothing is future- proof, but I have been happy with this:

https://www.mefoto.com/products/sidekick360-all-in-one

Note that MeFoto also makes 2 other variants—one for phones under 3” wide and one for wider phones; if you want to get the full range, be sure to look for the all-in-one variant.

That looks like what I had in mind! Definitely more securely held in the grips than what I’ve had in the past. Thanks for the suggestion and link!

You realize that Google’s method does it much the same way? Exposure plus algorithms plus image stabilization.

Thanks for the note. I didn’t know how google did it but I’m not surprised. My point is primarily about my mismanaged expectations from Apple.