Apple and Google Partner for Privacy-Preserving COVID-19 Contact Tracing and Notification

Apple and Google announced they are developing secure, privacy-focused changes to their mobile operating systems that would allow individuals to receive a notification if they had come in contact with people who later tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, the virus that can result in COVID-19. The two companies released preliminary technical information today, along with a roadmap for how they plan to proceed.

Tracing and notifying everyone who has come in contact with an infected person who has tested positive is a critical aspect of reducing its spread. In some countries, authorities have required cellular carriers and other companies to provide direct access to smartphone locations to identify points of contact and enforce lockdowns and shelter at home orders.

Americans are notably averse to government tracking, no matter the purpose. Apple and Google’s approach might provide enough assurance of privacy to assuage the concerns of dubious citizens in the United States and around the globe while also serving a critical public-health purpose.

The two companies said in a joint press release that the service will be opt-in and will require the use of apps to be developed and released by public-health authorities. In a briefing on 13 April 2020, company representatives said they had consulted researchers and examined existing frameworks around the world in developing their approach.

This rare collaboration came together quickly. TechCrunch reports that it started just two weeks ago with a group of engineers from both firms. The preliminary documents are sketchy in parts and contain typos, a rare situation with Apple, emphasizing the speed with which they were assembled.

In the first stage, Apple and Google will make private APIs (application programming interfaces) available in mid-May 2020 strictly limited to health agencies. These APIs will work identically across both iOS and Android and let public-health authorities modify existing apps or build new ones that leverage the tracing features. The companies will also build simple model apps that governments could either put their own logos on or substantially modify.

A second stage will appear “in the coming months,” and will build the tracing approach into Android and iOS at the operating system level. Enabling tracing and receiving a basic notification can happen without even installing an app, company representatives said in the briefing. An app will be required for someone to register a diagnosis of COVID-19.

Security expert Ashkan Soltani, former chief technologist at the FTC, said in a tweet that an authoritative source told him Apple and Google would provide access to the stream of data only to a restricted set of organizations, not generally. Apple and Google representatives confirmed in the briefing that only government-recognized public-health organizations could use the tracing APIs and access the stream of diagnosis data required to alert people.

First, let’s look at where some of the underlying techniques come from.

Find My Provides a Model

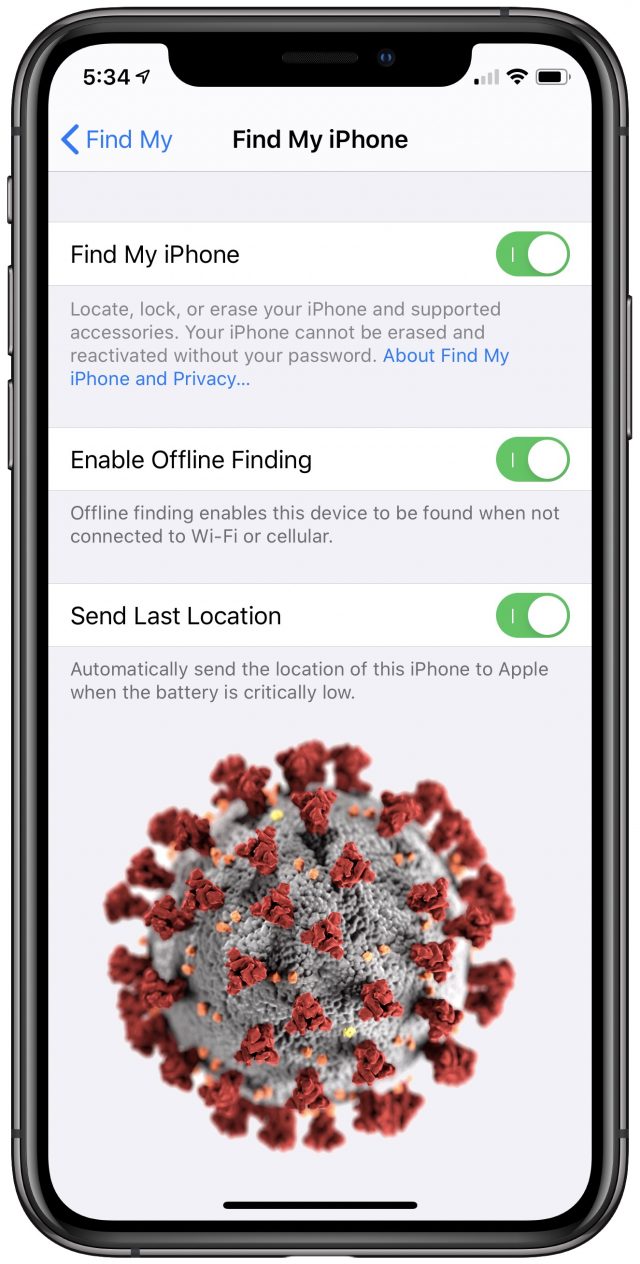

The new system bears a close resemblance to crowdsourced device-tracking systems already in wide use, like Apple’s Find My service, updated last year, and the Community Find feature from the RFID tracking add-on company Tile. These device-tracking systems require opt-in as well. (Apple’s option is called Enable Offline Finding. In iOS, it’s in Settings > Your Name > Find My > Find My iPhone. In macOS 10.15 Catalina, it’s found in the Apple ID preference pane in iCloud settings; click Options next to Find My Mac.)

Find My’s crowdsourcing feature requires two or more devices associated with the same iCloud account to be linked together, much like iCloud Keychain syncing. In the field, it works when an Apple device detects it has no Internet connection. It then begins broadcasting a Bluetooth beacon at regular intervals. The beacon has an encrypted value relying on key information shared among its set of devices. To prevent others from tracking the device via that beacon, the encrypted value changes routinely using shared information among its device sets.

Any other Apple user in the vicinity with a new-enough operating system detects the Bluetooth beacon automatically, combines it with its location information, and uploads that data to Apple. Apple lacks the cryptographic pieces necessary to extract details.

From another device registered with the same iCloud account, a user marks a device lost, and their device contacts Apple and provides enough information for Apple to return any matching uploaded bundles. The user’s device then decodes the packages from Apple and charts where and when a device was seen. The identity of users who participated in crowdsourcing isn’t revealed, nor do they know the contents of what their device is uploading.

Now let’s look at the new system proposed by Apple and Google.

Tracing Contacts without Breaking Privacy

The COVID-19 Contact Tracing Bluetooth system relies on the broad outlines of what Apple did with Find My. Instead of broadcasting over Bluetooth in limited circumstances, apps that use the new APIs will transmit a Bluetooth beacon at regular intervals, at least more frequently than every five minutes, based on preliminary specifications.

The API will generate a unique tracing key for each device that’s stored only on the device and never revealed. To protect privacy and prevent tracking, the system will create a separate tracing key every day that’s derived cryptographically from the device key. That, in turn, is the basis of creating a fresh proximity ID about every 15 minutes that’s broadcast over Bluetooth to be picked up by other people’s equipment. Listening devices store that proximity ID along with a timestamp. To preserve battery life, it relies on the Bluetooth Low Energy standard, so this recurring activity consumes a minuscule amount of power.

However, unlike Find My, the spec doesn’t require location information. It’s a possibility, but it’s optional, and the companies say any location sharing must have explicit consent:

The Contact Tracing Bluetooth Specification does not require the user’s location; any use of location is completely optional to the schema. In any case, the user must provide their explicit consent in order for their location to be optionally used.

People may be much more likely to participate in contact tracing if their location isn’t shared, despite assurances about how private the data is and how it will be used.

All these details become important only when someone tests positive for the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus. At that point, the infected person will need to choose to report their infected status by tapping a button or scanning a QR code in an app developed by a government health agency. Company representatives said that authorities may develop unique methods in their apps of validating a positive diagnosis to avoid people claiming they have the disease without a test or other criteria. (As testing remains constrained in many countries, some public-health officials include in their counts and use contact tracing for anyone who exhibits the typical combination of symptoms.)

However the test results are verified, once a user indicates they have a positive diagnosis, their app will upload the last 14 days of daily tracing keys to a “diagnosis server.”

The app will then launch daily for the next 14 days and send the previous day’s tracing key. That 28-day window will provide backward and forward tracing capability across the currently understood period of incubation in which symptoms may not be fully present and after someone is ostensibly no longer contagious—or has been admitted to a hospital for COVID-19 healthcare.

To preserve privacy for people who may have been in the proximity of the diagnosed person, their devices don’t push the information they possess to a server. Instead, the diagnosis server regularly pushes all reported daily tracing keys to every person with tracing enabled. (Access to the feed of keys will be tightly controlled.)

That might seem like a huge load, but even if hundreds of thousands of people reported themselves infected per day, the keys are relatively small and the data load will be distributed across time. Security researcher and Signal app creator Moxie Marlinspike speculated on Twitter that the tracing keys might be loosely location tagged to reduce the amount of data potentially several billion smartphones would need to download. That seems like a detail that will be hashed out as development progresses.

Checking daily tracing keys happens only on people’s individual devices. Each device uses a cryptographic transformation on the list of daily tracing keys to check each key against the rotating proximity IDs it grabbed over Bluetooth. If any match, that means that those two devices were in close proximity at some point, and the matching party’s device knows the timestamp of any recorded matches.

This clever technique preserves both anonymity and privacy. Only the person diagnosed possesses their daily tracing keys up to the point at which they are uploaded. Only devices in the proximity of that person would have received rolling proximity IDs derived from those daily keys. No other party should therefore be able to make a match. (Marlinspike did note that some advertising tech companies have Bluetooth-sniffing gear in retail establishments, making it possible that they could de-anonymize people who marked themselves infected. However, that would require direct access to the feed of daily tracing keys.)

This process also works to prevent errors and attempts to subvert the system, since each device knows the sequence and time at which it captured proximity IDs.

In the first phase expected to be released in mid-May, people will need an app installed to broadcast proximity IDs, receive and process matches, be alerted of a contact who has been infected, and report a diagnosis. In the second phase, users will be able to opt-in at the operating system level for everything other than reporting a positive test result.

(While this is the description in the joint cryptography API draft specification, company representatives in the briefing described a version that omitted the daily tracing key. I have been unable to get clarification as to the difference at publication time.)

Since the announcement appeared, many people have raised the concern that Bluetooth signals could reach far enough to cause significant false positives. Those who live in multi-unit buildings or in houses in close proximity often see Bluetooth speakers and headphones appear when they try to pair their own gear.

However, Apple and Google representatives said in a briefing that multiple markers would be used to ensure proximity. By measuring signal strength and capturing multiple proximity IDs, the contact-tracing framework would try to identify only people within a few feet for around 10 minutes. They said the system would follow metrics developed by epidemiologists on how the virus spreads over distance and time.

Alice and Bob Explain Contact Tracing

Here’s how we would explain the Apple/Google proposal in typical cryptographic analogies using Alice and Bob as examples.

Alice and Bob are in a grocery store at the same time. Alice’s iPhone receives several proximity key identifiers from Bob’s Android phone and dutifully records them. Two days later, Bob is diagnosed and uses the app to update his status. His daily tracing keys are uploaded.

Alice’s iPhone, in one of the regular updates it receives of diagnosis tracing keys, matches Bob’s key against proximity IDs it stored and enumerates all the matches with their timestamps.

The final version of the spec might perform additional checks: was Alice within an estimated 1 meter of Bob for two successive proximity ID captures? Were Alice and Bob close together for more than 5 minutes measured by timestamps? Did Alice receive 1000 proximity ID captures with weak signals, indicating they were merely neighbors and not immediately adjacent? Or is the signal so strong and appears so often that Alice and Bob likely live or work together?

Depending on the app and country and analytical details, Alice might be able to see various information about the match—potentially as simple as “you were in contact with a diagnosed party on 3 April 2020”—or have the option to disclose those details to a public-health agency.

The Right Path Forward

Together, Apple and Google can reach billions of smartphone owners worldwide and simplify the process for public-health officials to trace infection vectors. That could play a huge role in helping society move towards a greater sense of normality after the number of infections drops precipitously.

Adoption could be hampered by the large variety of devices in use, however. Apple and Google representatives said in a briefing that they intend to distribute the APIs and system updates across as many operating system releases as possible but don’t yet know how far back that will go.

Government authorities and political pundits have been calling for compulsory tracing of individuals by device, and some countries have rolled that out already. That’s bad, even during a crisis, because powers asserted by government to reduce our freedom from surveillance are rarely freely relinquished. However, many countries already have the legal power in a public-health emergency to obtain tracing information through in-person interviews, phone-call records, credit-card and transit purchases, and the like, and they have used it solely for that purpose in past outbreaks.

There could of course be flaws in the specification or the eventual implementations, although the fact that it comes from two of the most technically capable companies on the planet is a plus. Apple and Google are accustomed to their platforms being under constant attack. They also have special abilities when it comes to pushing updates. Couple all that with the fact that this proposed system is entirely opt-in, allowing those who aren’t comfortable with it to bypass it entirely, and it feels as though this may finally be an example of the tech giants bringing their unique skills and resources to bear on the pandemic, as Adam Engst suggested in “How Can Tech Step Up for Humanity?” (6 April 2020) .

We’ll be living with the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus for some time. This privacy-oriented proposal from Apple and Google appears to offer the right balance for social good and personal privacy.

Great idea, with a few caveats though.

First, Bluetooth is not a good technology for determining distance between devices, it is highly inaccurate for that. Since it really matters if two people are within less than a meter or more than 5, the chance of false positives will be very high. It is not clear to me how this is going to be resolved.

Second, the OS updates would need to be available for older OS versions also to be most effective. Android is pretty bad at making that happen, Apple could, but usually does not allow that to happen.

FWIW, one marker of transmission is being within 1 meter of an infected person. However, if an infected person sneezes or coughs in an area, the virus can contaminate surfaces within that area for a period of time, and touching that surface and bringing your hand to your face is also a likely transmission vector, so just knowing that a collection of people were within the same area that an infected person was at a specific period of time before symptoms were noticed (or a test confirmed infection) will be a good start for contact trace testing.

I take that back - we do know that BT can be used for close contact. Apple already does this with Apple Watch unlock of a Mac. You have to be within a few feet for it to work.

Yes, there’s enough information that the system might require a couple of data points within five minutes with similar strong signals. We don’t yet have those details, because it’s preliminary. So they can weight it.

There’s definitely concern that they don’t want you to be notified by a next-door neighbor’s diagnosis unless you interacted with them directly. But while Bluetooth through a wall can work, it is a far weaker signal.

A deep and sober consideration of contact tracing apps:

https://www.lightbluetouchpaper.org/2020/04/12/contact-tracing-in-the-real-world/

If the apps are to by done by public health agencies, then the question becomes which ones? County level there are over 3100 in these United States while at state level there are 56. It seems to me that the US Public Health Service should be the responsible agency for design and release of these two apps.

Also the apps MUST be backward compatible at least versions so as to not force someone to spend several hundred dollars on new hardware just to use the apps.

The companies are working with national health authorities, but those authorities could choose to designate other entities. Apple and Google will be making model apps (as noted in the article) that authorities can basically put their own name on and use, too. So we’ll see how split up it gets.

It’s not an apps issue—it’s a technology one. Bluetooth LE support is required so that’s a hard limit. Neither company wanted to promise specific generations, but the way they were talking, it sounded like they were trying to sweep in at least several years worth of phones.

On Android, the company representative in the briefing I received said they would use Google Play services, which they said gave them a very wide scope. We’ll find out more in the coming weeks, but their goal is absolutely as many devices as possible.

Nobody is trying to sell more hardware.

So for those that are interested, Singapore actually rolled a version of this several weeks ago. Called TraceTogether, to this admittedly non-technical reader, it sounds like it’s using a very similar approach.

I wonder how the cross-pollination of these ideas will work in these completely uncharted times.

I wasn’t quite clear on whether there’s anything one can do right now to assist this effort. Are the APIs able to retrospectively acquire the contact tracing data, or would I have to install an app in advance of contracting the virus?

I’m in the UK and it appears the NHS (National Health Service) have not yet released an app - https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/apr/13/nhs-coronavirus-app-memo-discussed-giving-ministers-power-to-de-anonymise-users

Yes, although without the OS integration and privacy protections. The briefing I attended openly acknowledged they were looking at all the best efforts worldwide.

In phase 1, an app is required that works with the private APIs that Apple and Google are developing. You have to have the app involved to opt into testing, automatically produce and monitor Bluetooth IDs, receive key updates, and report yourself with a positive diagnosis. Apple and Google will release model apps that agencies could simply adopt, too, if they don’t have the time or resources to integrate into an existing app or develop one from scratch.

In phase 2, the operating systems will incorporate the opt-in, Bluetooth component, and receipt of diagnosis with a simple alert. No need for app to start gathering data. But you will need an app to report yourself with a positive diagnosis and to do anything with the data your phone has, such as provide it to a public-health agency.

The data is not being collected retrospectively. Once phase 1 apps are released, you have to opt-in to start data broadcasting and collecting.

Surface contamination is indeed a method of virus transmission, which is the reason washing your hands is so important. But Bluetooth can’t even detect if you’re in the same room. It could be a signal from someone walking by outside the room. Even someone driving by in a car. Bluetooth just cannot determine distance accurately enough.

Unlocking a Mac is a very specific use case. Like you said, you need to be very close, much closer than the distance advised to prevent contamination, with nothing between you and your Mac but air. The Bluetooth signal will be very strong then, which is probably what makes the unlock work.

I was replying to Doug Miller’s posts, but apparently replying does not automatically quote the message one replies to. Sorry about that. I guess I need to educate myself on how this forum works.

Taken in isolation as a single measurement, probably. Although a weak Bluetooth signal can indicate a sensed device is far away.

But as I note in the article, the design of this system will rely on multiple measurements over time. It’s possible that the Bluetooth scan will measure signal strength over a few seconds, too, and only record a proximity ID once.

The company representatives on the briefing call I was part of said that the system is specifically being designed to ensure close proximity and specifically called out that it would be resistant to someone driving by and through a wall or far away. With multiple measurements across a period of time, a smartphone can infer and model a lot of information.

When you’re doing very specific replies, select the text to reply to and click the Quote button that appears. You can do that multiple times, even with replying to bits from multiple posts, so you could have a single post that would reply to each of the points you make above.

FWIW, I just tried a couple of experiments. My Mac unlocked when I was standing with my watch exactly 5 feet away. My Mac would not unlock when I was 7 feet away.

I still say this is good enough for contact tracing even if it is collecting all of the contacts that were within BT range for enough time and at a period of time when somebody was found to be possibly infected but asymptomatic. Think of all of the people in a grocery store for any 15 minute period between 10:00 and 10:45 when I was roaming the store 5 days ago after I’ve tested positive after first showing symptoms. It’s probably better to test too many possible close contacts than too few.

That’s part of the question, and I wonder if how the service will work with that. Say if one country wants to test anyone who was in the same restaurant as anyone who later tests positive and another only wants people within 10 feet for at least 15 minutes? I figure there’s some room for variability, but the system has to make a lot of determinations.

One of my unanswered questions is how much information is stored alongside the proximity IDs that other devices are broadcasting. Is it just the ID and a timestamp? The companies say location information isn’t required and in the briefing they said explicitly that the system doesn’t rely on location.

But there are other ways to combine Bluetooth and relative location determined by GPS and other systems without disclosing one’s absolute location on the planet—or that information could remain in-device and only be used by the system to confirm location matches, and then discarded.

It was clear that you were replying to Doug as his statement did appear at the bottom of the email I received from you.

That’s just not true, as others have indicated. Although BlueTooth can be detected at greater distances and though walls, the strength of such signals can easily be determined and programmed to reject all those that don’t exceed a specific threshold or that are not being received continuously over a prescribed period. I would hope that the apps will be carefully designed to reduce the frequency of such false detections.

Thanks, I got it! Great feature. :-)

I agree that could reduce false positives, but that was not clear to me from the technical documents I read.

Interesting. So yes, Bluetooth can detect if another device is nearby, but that is not the same thing as accurately measuring distance. For example, I would expect you would need to get closer if someone was between you and your Mac. The Mac unlocks when some signal strength threshold is passed, but that does not necessarily equate to a specific distance.

That is correct, however that does not necessarily exclude signals coming from outside a room. For example, in apartment buildings, Bluetooth signals from a neighbor can easily be as strong as those from yourself. So basically, what I wrote is true. You might be able to reject many false signals, but certainly not all. And the more signals you reject, the higher the chance you also reject correct signals. So whatever algorithm they come up with, it will be a compromise.

The big question is, how dependable will this app be? Will people trust it? You need to be significantly altruistic to use such an app, because it will not protect you from Corona, it is meant to protect others. Nothing wrong with that of course, but if the app makes people go into quarantine wrongly, trust will fly out the window and people will stop using it. So they better get it right first time.

Off-topic.

On the same line as your name, just to the left of the relative time (for example, it says 22h as I type this), there is an indication that your post responded to @ddmiller’s post. When I clicked on the arrow indicating a reply, I was shown the post to which you were replying, with the option of navigating to that post.

Until I learned that trick, I was occasionally frustrated when someone did not quote what prompted his or her reply.

That’s not my understanding. I believe it’s designed to provide contact tracing statistics to medical analysts to better understand how it’s spread. It may also help to protect others in the process, just not what it’s been advertised.

Perhaps it is different from country to country. Yes, contact tracing statistics is one goal, but where I live the main goal would be to prevent the virus from spreading by reducing the R0 (factor of number of other people someone infects) to below 1. This can be achieved by (self) quarantining anyone that has (potentially) been in contact with someone that has, at a later time, been diagnosed with Corona. By (self) quarantining after the app warns you, you protect others.

Apple and Google announced today via a background briefing that they are released a beta version of the API for COVID-19 exposure tracking. It’s being released only to a subset of developers associated with public-health authorities; not a general release.

The two companies also said today that they will allows public-health authorities to set parameters around the exposure levels they consider important to inform others about. In earlier drafts of the standards—as discussed in this forum—there were questions and not a lot of answers about how Bluetooth positioning data could be used to ensure only close-contact matches would be made.

In this revision in the beta process, the companies say that developers can incorporate this data from public-health authorities into the apps so that the apps can provide information appropriate to the distances and time exposed. All of the exposure information will remain on each individual device, so no central authority will be able to access it. However, the apps can use the API’s analysis of proximity and duration to offer up custom details.

While the companies didn’t offer guidance to what that would look like, my understanding is that it could be the difference between, “On 14 April, you were within 50 feet for more than 30 minutes of someone who has tested positive for the novel coronavirus on 18 April. Contact xyz to discuss testing” and “On 14 April, you spend 15 minutes within five feet of someone who has tested positive on 18 April. Please immediately quarantine yourself for 14 days from all contact with other people, and contact XYZ for information about obtaining in-home or in-car testing.”

Reuters is reporting that Apple and Google’s contact-tracing API will ban developers from accessing GPS data.