Apple Unveils Stringent Disclosure and Opt-in Privacy Requirements for Apps

In late 2020, Apple rolled out its new privacy guidelines for apps, which require explicit and detailed disclosure by apps of their collection and use of personal data. In the near future, it will also require that apps get opt-in permission to track users by any personal identifier or a device’s unique advertiser identifier.

These two changes have roiled the online advertising industry, which has unfortunately shifted over its 25 years in existence from being excited about counting clickthroughs and measuring them against actions to luring users into a deliberately invasive stew of misdirection and obfuscation. By and large, the industry prefers that people don’t know how much their private information is being extracted and used, and it hates having to ask for permission—because it knows most people will say no.

The online advertising industry claims that advertising success is possible only through highly targeted advertising, in which each ad that appears on your screen is the result of a billion billion calculations of everything known about you, including your clicks and visits from mere moments ago. While that claim about success may or may not be true—an increasing amount of evidence, noted below, suggests that it is not—the industry has become dependent on concealing what it does with our information, fearful that if it were known, the house of cards would come crashing down.

This blog post from Invoca—a company whose business I cannot figure out exactly because the ad and marketing industry has become so very baroque—explains the insider view of Apple’s moves. The headline reads, “What Is IDFA and Why Apple Killed It.” IDFA is the device-based advertising identifier Apple attaches to its hardware, which functions like a browser cookie for a device and which users can reset whenever they like. However, when you dig into the post, it turns out that, despite the hyperbolic headline, the author actually says:

Apple hasn’t ‘killed’ IDFA per se, but has made tracking in apps an ‘opt-in’ situation in iOS 14 as part of the company’s continued focus on user privacy.

In other words, Apple is blowing like mad on that house of cards.

Among the top tier of tech companies, Apple is the only one that places its customers’ privacy in its list of central concerns—and means it. Other big firms flap their gums about how privacy is important, then routinely lobby for loopholes, pay small fines for violating regulations, or construct methods that deceptively violate user consent.

While Amazon and Google have their own issues with disclosure, tracking, and consumer violations in the US and internationally, the biggest privacy abuser is, of course, Facebook. Facebook’s business model appears to rely on routinely violating its users’ privacy and then promising to do better, which it never does.

Apple has progressively clamped down on user tracking in Safari and apps over the last few years, describing such efforts as part of its mission to create a safe and generally “opt-in” Internet, in which your online activities remain protected and private unless you choose otherwise. Apple’s new app-based disclosures and the requirement of consent to track outside of the app continue its evolution in insisting on customer privacy.

Signs are already visible that the whole edifice of the online ad industry may be due for a collapse. So much of the money collected ostensibly on behalf of publishers is sucked up by ad tech firms, ad fraud, and intermediaries that half or less reaches the actual sites. Some research suggests it’s as little as 30 cents on the dollar.

Other examples of a possible adpocalypse?

- JPMorganChase reduced its advertising reach from 400,000 sites to 5000 and saw no change in outcome.

- Uber audited its ad spending to generate new users and went from $150 million to $20 million in spending without a drop in actual leads.

- Proctor & Gamble slashed $200 million in online spending and found its reach increased.

- eBay cut $100 million in ad spending without a drop in referred sales.

For instance, try to explain why, after you purchase a given item, ads for that same item chase you around the Internet. Ad efficiency? Hardly.

Apple’s privacy moves might topple some dark ad giants who don’t deliver for advertisers (or publishers) and have managed to hide their incompetence behind Rube Goldberg contraptions. It’s not unthinkable that Apple could help sweep in a simpler, more direct, and less intrusive advertising that resembles the Internet’s earlier days.

That’s probably too optimistic, but let’s start with the changes Apple has already made and the opt-in requirement on third-party tracking about to emerge.

From a Single Line to Pages of Revelations

Apple’s new disclosure requirements are relatively easy to understand and summarize. Apps must disclose what data they may collect, and whether that data is linked to users, stored outside the app, or used to track them. In terms of simplicity, it’s fair to compare them to the nutrition facts label on packaged foods, thanks to the standardized format and language. But, just like those labels, it’s worth noting that the data is self-reported. Apple’s role in monitoring and verification is unclear, and there are a variety of exceptions.

Developers who have conformed to Apple’s privacy rules in the past, to the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (as of May 2018), and to the California Consumer Privacy Act (in effect from January 2020) should already have gathered all of this information and provided it in one or more policies within the app and on a website. That should be effectively all developers, even one-person firms, because of the broad scope of those existing laws, rules, and Apple guidelines.

What Apple calls “app privacy details” systematizes and makes simple all the kinds of data about you that an app collects, including via embedded third-party code, and how the developer handles it. Instead of reading a lengthy privacy policy that could be written to any standard, Apple’s details use standardized terms and top-level icons. (The GDPR nominally requires language in privacy disclosures that’s plain and easy to read, but it provides no assistance in doing that, nor does it seem to enforce the prohibition on confusing language.)

Apple offers developers an equally straightforward description of how to collect and provide all the necessary information. The general principle is that any data that’s collected or inferred by an app and sent off-device for “a period longer than what is necessary to service the transmitted request in real time” must be disclosed. For instance, someone might provide their email address to an app for it to retrieve some piece of information, but if the app’s developers and any connected third parties immediately dump that email address after the retrieval, it doesn’t seem to qualify as “collected” in Apple’s definition. (Please note that I am not a lawyer, and this article doesn’t constitute legal advice.)

The app privacy description covers which categories of data might be collected, providing specific examples for each (such as location, financial, contact information, and the like), how it’s linked to the user (and how to avoid such linkages), and how an app developer or affiliated third party might track a user based on collected data.

Apple also makes it clear that there’s a big difference between on-device and off-device tracking, personalization, and data usage. An app can download and cache marketing information, including from third parties, and then apply personalization or other behavior within the app based on locally stored personal information and the advertiser identifier. As long as that information isn’t then sent off the device, it doesn’t have to be disclosed. (This principle is similar to how Apple has allowed companies to provide phone-number spam identification, by allowing databases of numbers to be downloaded to an app and then compared only locally against incoming phone numbers.)

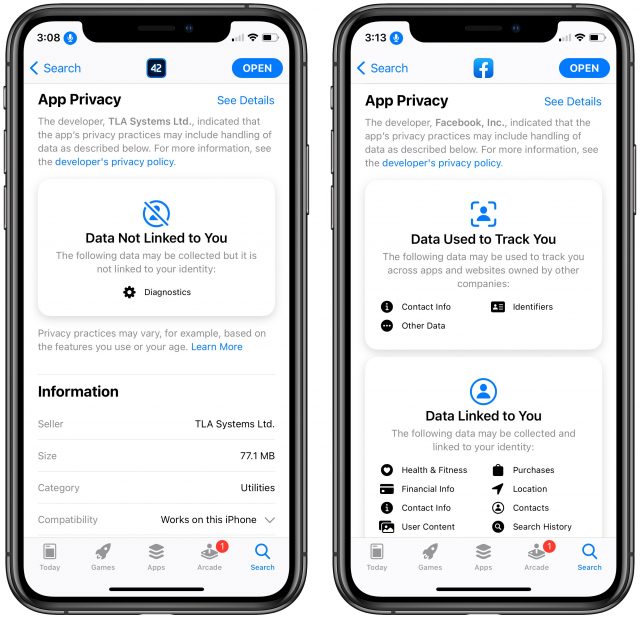

These privacy details are presented in Apple’s various App Stores in an App Privacy panel below version history. Under Data Linked to You, it specifies all the categories of data, with distinct icons, that are being used. There may also be a Data Not Linked to You section that discloses (sometimes optionally) data that’s collected either only on-device or for diagnostic purposes, or that is not retained after a lookup or retrieval. Tapping or clicking See Details provides a more thorough item-by-item accounting.

The range of disclosure can be mind-bending. James Thomson’s popular calculator app, PCalc, collects diagnostic data that’s not linked to the user in any way; it gathers nothing else. Facebook’s disclosure, on the other hand, runs to ten iPhone screens.

Apple, by the way, does not require that app developers disclose information that Apple itself collects through the use of Apple frameworks and systems, like advertising or in-app purchases. Apple already has agreements as a “first party” with the user of an app in order to use an iPhone, Mac, or other device. It has disclosed terms and required acceptance of licenses and data-collection policies as part of a user setting up a device and signing into a given App Store on it. Those terms and agreements may not be as clearly displayed or worded as would be ideal, but we can hope that Apple will be working to improve that user experience as well. (Apple lets you opt out of some of its tracking and collection, too, as I detail at length in my book Take Control of iOS & iPadOS Privacy and Security.)

Apple’s apps, however, do have their own App Privacy listings. Pages notes that it might link “Contact Info, User Content, Identifiers, Usage Data, and Diagnostics” to you. That seems like an awful lot of linkage for a word-processing app. However, when you click See Details, Apple clarifies that it uses most of the data for analytics (measuring usage and what people do), while only using a few pieces of information for customizing the app, and that it has access within the app to user content (photos, video, data, and other documents).

As always, the question is whether disclosure prompts changes by individuals. The App Privacy listing is just a disclosure: users can’t opt in or out of different kinds of data collection—it’s all or nothing. But unlike a standard software EULA (end-user license agreement) or dense privacy policy, Apple’s requirements and presentation make it quite clear what’s up, assuming the developer has been truthful, of course. Then you take it or leave it: you either buy or install the app or don’t.

However, Apple is about to enable an option that will give you choice over one set of items disclosed in App Privacy. Sometime soon—the company hasn’t yet said when—Apple will require that you opt into third-party tracking. That’s what has Facebook quaking, and what I’ll explain next.

The Holy Grail of Permission-Based Marketing and Advertising

What could have terrified Facebook enough about Apple’s upcoming App Tracking Transparency requirement that it took out a full-page ad in multiple newspapers and created an accompanying website alleging that Apple’s update would endanger small businesses? It’s this little message, as Tim Cook noted on 17 December 2020 in a tweet (see “App Store Wars: Facebook vs. Apple, Publishers vs. Apple, Apple vs. Brave,” 17 December 2020).

We believe users should have the choice over the data that is being collected about them and how it’s used. Facebook can continue to track users across apps and websites as before, App Tracking Transparency in iOS 14 will just require that they ask for your permission first. pic.twitter.com/UnnAONZ61I

— Tim Cook (@tim_cook) December 17, 2020

Facebook characterizes this message on its advocacy site thusly: “Apple’s new iOS14 [sic] policy requires apps to show a discouraging prompt that will prohibit collecting and sharing information that’s essential for personalized advertising.”

To paraphrase: Facebook’s entire advertising model is so fragile that if users were given the information to choose between having their information shared willy-nilly and relying on Facebook to preserve their privacy, advertising results would collapse. That would be a damning admission, no?

Even some Facebook employees thought Facebook’s stance was a bunch of hooey, according to Buzzfeed News. “It feels like we are trying to justify doing a bad thing by hiding behind people with a sympathetic message,” one engineer wrote. Another worker reasonably asked, “Why can’t we make opt-in so compelling that people agree to do so[?]”

Facebook won’t be the only company whose apps will trigger this new transparency alert, of course. All apps that send information Apple defines as providing a way to track a user outside that developer’s “first-party” ecosystem will have to present and honor a similar dialog. For some apps, that might be just the app; for others, the app and servers or other resources organized under an associated domain. For still others, it could be broader and encompass a range of networked hardware and services.

In other words, Facebook doesn’t need to display such an alert to share tracking identifiers from the Facebook app on an iPhone with the Facebook website someone might access from a browser on a Mac. But after passing data to and from the Facebook website, the company can’t pass any tracking identifiers to other parties. To make its targeted ad approach work, Facebook—or any company that shares information with data brokers—would have to display the tracking prompt. (Apps can also share and use certain identifying information to deter or detect fraud and for security purposes.)

But there is a red line: if a company shares information that can track a user outside of stuff it owns or operates on its own behalf, this transparency requirement is triggered. How Apple will enforce that, for companies with expansive services, remains to unfold. Can Facebook track across its Instagram and WhatsApp subsidiaries without an alert?

This tracking prompt will appear the first time you launch an app after Apple enables App Tracking Transparency. If you later change your mind, you can make modifications in Settings > Privacy > Tracking. Apps can explain why the pop-up appears, or they can rely on a generic message. (This approach is very similar to Location privacy, which Apple has tightened over multiple releases of iOS and iPadOS in response to developers and ad networks creating workarounds and exploiting loopholes.)

Notably, apps cannot require you to opt into third-party tracking in order to use the app. As Apple notes in its developer FAQ: “[Q] Can I gate functionality on agreeing to allow tracking, or incentivize users to agree to allow tracking in the app tracking transparency prompt? [A] No…”

The Electronic Frontier Foundation argues that Facebook’s campaign against Apple has nothing to do with users or small businesses. Instead, the EFF suggests, Facebook is attempting to shore up a business model that relies on abusing privacy and to distract from its anti-competitive behavior.

But the EFF’s primary, seemingly obvious stance resonates even louder:

We shouldn’t allow companies to violate our fundamental human rights, even if it’s better for their bottom line.

Blow on that house of cards, Apple, blow.

Apple Isn’t in the Business of Treating Its Customers Like the Product

Critics and cynics will note that Apple doesn’t have to play nice with advertising networks because only a minuscule portion of its massive revenue stream comes from ads. Such people might suggest that deploying restrictions that could reduce ad revenue to Amazon, Facebook, Google, and even Microsoft, would hamper their efforts to challenge Apple’s hardware ecosystem or develop competing apps and services. (You may not think of Microsoft as being focused on advertising, but the company generated a surprising nearly $8 billion in ad revenue in its 2020 fiscal year.)

But it’s hard to see Apple needing to resort to using privacy as a weapon to hurt other tech giants. Amazon makes its money selling all kinds of stuff, and even its hardware that does go head-to-head with a few Apple products—the Echo smart speakers and Fire TV—is up against the HomePod and Apple TV, which are perhaps Apple’s lowest-selling hardware products. Google’s Android operating system derives revenue from advertising, and a recent filing from the US Department of Justice states that Google pays Apple $8 to $12 billion a year to be the default search engine on Apple devices. Microsoft exited the mobile business, and despite the scale of Windows, the company has refocused its efforts into making its apps and services available on every platform, including Apple’s. Privacy may be a selling point for Apple, but overall, the company isn’t using it as a competitive cudgel against other companies.

Tim Cook’s consistent, principled stance in nearly all aspects of user privacy—including apologizing and making changes when flaws or exceptions are discovered—can be both sincere and a marketing tactic. But just like, say, Walmart’s move towards renewable power and reduced emissions, we can accept the benefit to society while keeping a gimlet eye poised to watch for failures or misleading statements.

In the end, there’s nothing wrong with Apple’s efforts to reduce the amount of undisclosed, unwanted, and opt-out forms of tracking across the Internet, even if they end up puncturing the cash balloons of parasitic data brokers, intermediaries, and ad tech firms.

In a not-unrelated development, Facebook corporation is now requiring Whats App users to share data with Facebook to continue to use Whats App. (Given the antitrust scrutiny on Facebook right now, this change is from a political and anti-trust/legal perspective, just insane…)

Yes - there is an analysis here:

Consolidating data will enable more precise ad targeting, yielding hundreds of millions more in revenue. It will also make it harder for the EU or US to break up the company, maybe even enough to prevent the courts from demanding it. IIRC, Zuckerberg swore up and down that he would keep WhatsApp separate when he bought it, but I don’t think anyone in their right minds ever believed it. I’ll bet Facebook will slowly but surely consolidate all their products. Something else Facebook might be betting on is that more consolidation will make it even easier for individuals to rile up users across services to spread disinformation and incite violence.

I find this rather ironic…Facebook pulls this crap immediately after launching grenades at Apple for doubling down on its privacy policies.

Settings > Privacy > Tracking > Learn more reads “When you decline to give permission…App developers are responsible for ensuring they comply with your choices.”.

Developers can fingerprint by other means than the official advertising id controlled by Apple. And they do.

Right, and privacy researchers and Apple are constantly finding out when this is done, and such app developers get suspended or permanently removed. These new rules will come with even tighter supervision.

If I look at the source for the TidBITS mailing, I can see that it downloads a 1x1 pixel image. I’m assuming that this is used for tracking purposes. What does TidBITS do with that information.

This is my guess, and it comes from a background in ad sales and marketing, as well as from being a longtime TidBITS reader and a Talker from the day this list started. Embedded pixels are not necessarily evil. They are used for internal tracking and serving about as much as external. It how Discourse keeps track of the number of days and times you have visited the TidBITS site, which articles you read and which articles and posts you responded to.

It provides Adam & crew with vital information about what coverage readers and Talkers are most interested in. It lets them know which articles and Talk posts people return to, as well as articles that non subscribers stumbled upon via a web search; it will also let them know if a new visitor returns and/or becomes a paid subscriber. They also provide information about how many people are reading articles or posts via email or the Discourse site, and they can learn about how many email subscribers actually open every email, how many people respond to them.

Just a few days ago I asked for recommendations about keyboards and trackballs for my husband’s new M1 MacBook Pro, and I got some excellent recommendations. Although I am risking the Malocchio, I did a lot back and forth checking and responding, when moving around the web I did not see a single ad or email for keyboards, trackballs, mice, or any other related products having to to with Macs or iOS stuff. The moral of the story…don’t worry about TidBITS selling your cyber soul to the devil. I certainly don’t.

Sendy, the software we use for interfacing with Amazon SES for email distribution, uses that 1x1 pixel to determine whether or not the issue was opened. I like to see that information to get a sense of what percentage of our email subscribers are reading (or at least opening) the issue.

We average about 45% open rate for issues. For TidBITS members who receive every article (the other three lines in the screenshot), we usually see open rates a bit over 50% for Watchlist items and around 65% for other articles.

Interestingly, until this week, Sendy also modified all the links in the issue to track the number of unique clicks. We never cared about that data at all and didn’t want our links modified, but it wasn’t technically possible to shut it off until Sendy 5 shipped and our developer had a chance to change the API calls we use to create campaigns.

I appreciate your candor, but I still have concerns.

There are other issues besides what TidBITS does with the information. For example, what does Sendy do with the information? See I never signed up for this! Privacy implications of email tracking. https://petsymposium.org/2018/files/papers/issue1/paper42-2018-1-source.pdf

I use Apple Mail. In Mail > Preferences… > Viewing I keep “Load remote content in messages” unchecked because I just never know what anyone does with the tracking information.

Absolutely agree! I never let remote content load automatically in incoming mail. So TidBITS may think I don’t read every article, but in fact I do, and only load images (and any tracking pixels) if there’s obviously something necessary to understand the content.

It’s much too simple for the site sending the pixel (or any content) to get a enormous amount of info about your browser and machine, usually enough to uniquely identify you. (As Facebook does, even if you don’t have an FB account.)

Nothing. Sendy is an app installed on our server and never gets the information.

If you avoid loading images, which is certainly your prerogative, you wouldn’t be counted in the open rate. That doesn’t bother me at all—I like to know roughly what percentage of subscribers are actually reading our work, but there’s no need for precision.

That may be true for other sites. The only data we get out of it is open rate. I don’t know, nor do I care about, what other information might be determinable through this method.

The only Web tracking we do is Google Analytics for analyzing article popularity and the only email tracking is this pixel for open rate. I doubt you’ll find many other tech news sites that do less. In particular, we don’t use any ad network for serving ads, so there’s no third-party tracking there, which you’d find on nearly every other site.

This is true! The only one I can think of is Daring Fireball, which to my recollection, uses a simple image + URL click for ads (no other tracking), and doesn’t send out email (only uses RSS and Twitter for pushing stories outside the site).

I love not loading images for lots of reasons, including this one. I use Mailsmith (32-bit, sob, will someday have to migrate off or virtualize it), which shows no rich contents (text only); and Postbox, which has good, granular image-loading controls. I can set it to allow images to load only from specific domains I approve, which has been useful.

I would assume also that Amazon (who is preparing the dashboards you see) has a database of who has read each mailing, along with the HTTP environment that accompanies the request.

But, as has already been pointed out, these images accompany mailings from all kinds of sources. Fortunately, most mail clients (even web-mail ones) provide mechanisms for not downloading external images from mail messages. The only problem there is that it’s usually not selectable on a per-image basis, so you may be out of luck if the message has images you want to see in addition to the tracker.

On the other other hand, any image downloaded, even ones containing the content you watch, also create trail that can be mined by whoever is hosting the image, so a person who is serious about this shouldn’t be downloading any images at all.

It’s possible, but the screenshot I posted was from Sendy itself, running on mailer.tidbits.com.

As far as I know, Amazon only knows about email addresses on my list in a transient fashion, while sending, or if they bounce. And with bounces, even I can’t see a list of bounced addresses. If someone bounces and needs to be reinstated, I can paste their address into a CAPTCHA-protected form on Amazon, and if I get the CAPTCHA right, Amazon SES tells me that, if the address was on the bounce list, it was removed.

This is why I personally never stress about loading images. I don’t care enough, and I don’t want to put the extra mental cycles into deciphering messages that assume graphics in some way.

We include a fair number of images in TidBITS issues, and we do so only when we feel that they illustrate what we’re writing in some useful way. No one is forced to look at them (or to read anything we write, of course), but not loading them will detract from the overall reading experience. And all it will do is hide from us the fact that the recipient opened the message; given that the recipient presumably trusts us enough to have subscribed in the first place, it seems excessively cautious. But hey, as I said, whatever floats your boat.

I hear you, @ace. I would in principle like to turn off auto image loading (not because of mailings like yours), but I find it just too tedious to have to repeatedly select to load images from senders I trust. I’d love for Mail to allow a default setting and then on top of that a per sender setting that is preserved and overrides the default (kind of like how Safari does Reader view or content blocking). With something like that in place, I’d leave the default off. But as it is today, with one size fits all, I find leaving it off just interferes too much with my workflow.

Another new twist to the same old story:

Safari’s privacy report tells me tidbits.com uses one tracker only. Well done. I was shocked to discover arstechnica.com to be the worse offender instead with well over 70 trackers. What they even do with so many is a mystery to me.

By default, Thunderbird blocks all images, but you can turn it on for individual messages or individual senders.

I firmly believe that a lot of the trackers on these sites are there because the people in charge tried a new ad network or installed a little snippet of JavaScript to do something cool without realizing it came with trackers. Do that for a few years and you end up with a lot of crud. That was one of our design goals when we redid our site a few years back—eliminate all the crud.

The main thing that’s preventing me from ditching Google Analytics entirely is being able to access historical usage data and compare across time. The WordPress Jetpack plugin does analytics as well too, which I turned on a few months back. Once I have a year of data in that for comparison sake, I may turn Google Analytics off. I’ll have to see if Google Search Console is related to that as well, since I do rely on that to tell me when there are crawling errors on the site.

ars technica showed only 2 trackers for me (amazon and double-click). I am a subscriber, though and see no ads. I topped at 57 trackers for yahoo, dropping to 35 for next on the list.

A site like Ars (and the Economist among many others) participates in a ton of ad networks simultaneously, and some of those ad networks required the use of other third parties, and so on and so on. I realize everybody is trying to make some money, but the continued ad-blocking backlash is entirely to be expected when webpages crash or sites don’t load. There are several sites I simply can’t visit (and they are sometimes run by major media companies), because I can’t even scroll down a page without ads leaping at me, filling the screen, shifting the text, etc. If enable ad blocking, the sites won’t load or break entirely.

Such companies make the decision for me. If I am required to let you spy on me to use your website, the short polite answer is “no.” (The actual phrasing usually involves something physically impossible.)

I have 50 trackers listed for wired.com with the same owner of Ars. One more reason to subscribe then.

I believe this the most likely explanation.

Condé Nast, one of the largest global publishing companies, bought Ars Technica years ago. Among the many publications they own are The New Yorker, Wired, Vogue, Vanity Fair, Epicurious and many more. Condé Nast is owned by Advance publications, which also produces many respected newspapers and broadcast properties. They have a very complicated, and IMHO, interesting, relationship with ad blockers that began well over a decade ago:

Without page views and clicks, they’d be out of business lickity split.

Google has said it’s going to move away from tech that tracks people across sites. The Wall Street Journal has an article about that here:

https://archive.is/iPM0A

I think it’s a really good step in the right direction, but it’s a little baby step. It doesn’t cover Google services, including YouTube, Blogger, Gmail, Google Maps, etc. And their third party ad networks, like DoubleClick’s AdSense, AdMob, Ad Manager, etc. aren’t a part of the plan either.