CES 2022: Another Year, More Tech Trends

You may be forgiven for feeling as though it has been ten years since last January, but in truth, only a year has passed—and that’s long enough for another CES to be underway in Las Vegas. As usual, the show begins with two Media Days with information for the assembled press; as per “the new usual,” these events and a portion of the rest of the show is being broadcast in hybrid format online. I was exceptionally unhappy with last year’s CES online format (see “CES 2021: Multi-Port iPad Cases, MacBook Pro SSDs, Videoconferencing Cameras, and a Plane You Can Drive,” 11 February 2021), and so I’m equally unhappy to be one of the people attending virtually. But given the forthcoming tidal wave of Omicron COVID-19 cases (which I wish to neither contract nor spread), as well as the thousands of flights canceled in the week I would have been traveling, it seemed wise to log in to CES remotely for another year.

One highlight of Media Days is the Consumer Technology Association’s Tech Trends to Watch presentation. It’s irrepressibly upbeat and staged to spin the positives of consumer tech, as one might expect, but it always contains interesting numbers. But there was a big dog in the room that wasn’t barking: this year’s presentation said much less about COVID-19 than I expected. Steve Koenig, CTA’s Vice-President of Research, who gave the presentation as usual, referred several times to “the season of the pandemic,” which makes me wonder if he spends too much time in Westeros, where the seasons span many years. Two years into the closure and partial reopening of… let’s call it Earth, only 62% of Americans are fully vaccinated and 21% have had booster shots; worldwide, those numbers are 51% and 7%, respectively.

The last two years were enough time for two highly infectious COVID-19 variants to emerge, while the unvaccinated population acts as a reservoir and spread vector for new ones. Given these facts and vaccination numbers, I don’t see a clear future boundary line at which point we can declare Mission Accomplished! and call the pandemic over. Instead, I expect we’ll settle into a semipermanent new normal as communities continually adjust to pandemic rates just as they do to changing climate. This recognition was absent from Koenig’s presentation, which struck me as a glaring omission considering how vital technology has been in our societal adaptation to the pandemic. I would have been much more reassured by a statement along the lines of, “This is how we see the pandemic developing over the next few years, and these are the actions we see the tech world taking to ameliorate its impacts.”

The Tech Economy Is Just Fine, Thanks

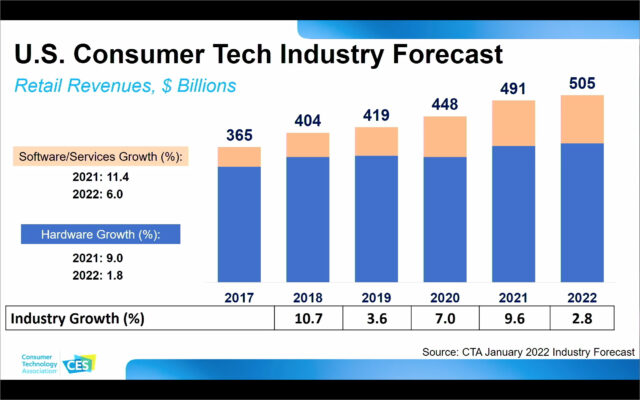

We might all be spending more time at home, but many of us have money to spend, and we’re spending it on tech. Consumer tech sales are forecast to pass the half-trillion-dollar mark in 2022.

Not highlighted in Koenig’s presentation, but striking in the bar chart, is that it seems that hardware sales increases have been small over the past five years—the real action is in software and services. Or, to rephrase it in consumer terms, how often do you buy a new TV set versus how often do you subscribe to a new streaming service? And have you accelerated that spending since the pandemic changed your habits? Koenig specifically drew attention to this segment in a later slide, with the top four streaming services ranging from 20 million to over 200 million subscribers.

Note that these numbers may not be directly comparable. Amazon’s Prime Video has 175 million subscribers by dint of Amazon Prime delivery services having the exact same number; the two services are bundled and can’t be purchased separately. The number of Prime viewers is almost certainly a fraction of its claimed subscribers. Likewise, Apple TV+ numbers are bumped up by anyone who purchased an Apple device and turned on the 90-day trial, and anyone opting into an Apple One service bundle. Only Apple knows how many of its subscribers are viewers—or how many show up only when new Ted Lasso episodes are airing. Compare with Netflix, the juggernaut with 214 million subscribers and a name that has almost become a generic verb for watching a streaming service, and Disney+, which has reached 118 million subscribers after only two years in operation with a much less diverse back-catalog of shows—although obviously, highly desirable ones.

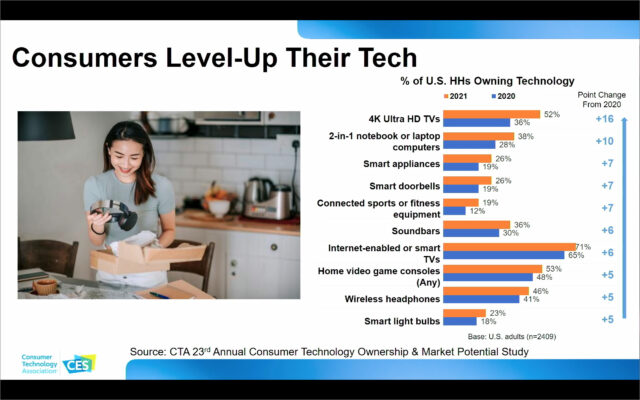

Koenig proposed that consumers are “leveling up their homes” with new technologies in response to the pandemic, but I don’t see a rosy picture for hardware sales in the next slide.

The biggest jump here is in 4K TVs, but I wonder whether that’s people who set out to upgrade their TV to a higher resolution or who simply decided it was time to buy a new TV of whatever quality and found that 4K TVs fell within their price range. (Especially considering how many people’s price range expanded from money not spent on eating out and going to theaters.) It paints a different picture depending on whether consumers are seeking out high-tech options for their electronics, or if they’re taking those options because they’re now standard, or even unavoidable, in the price ranges they’re willing to buy. You may not want wireless headphones, but buy a recent iPhone and that’s what you’re going to be using.

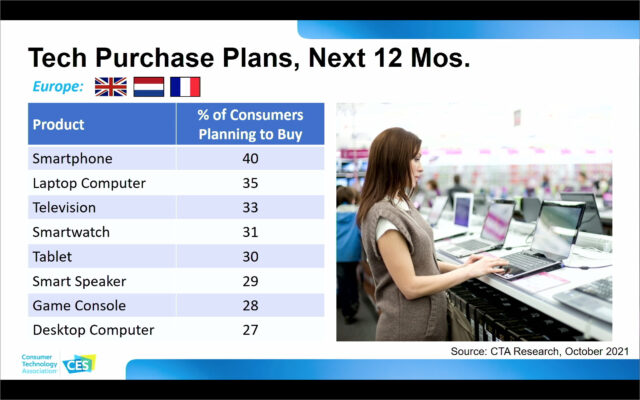

Similarly, it may sound exciting that 40% of Europeans are planning on a smartphone purchase in the next year, and 27% of them will buy a new desktop computer—but that is also what you’d find if both categories had no new customers and existing ones replacing their current gear on a 2.5–4 year cycle.

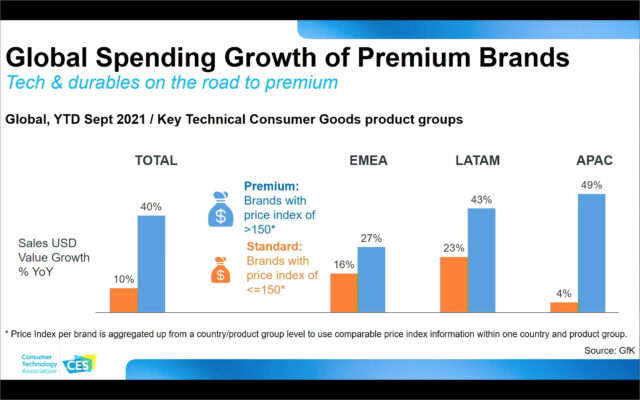

There are, however, two genuine bright spots in CTA’s numbers for the tech industry. The first is that by the measures CTA has formulated for what constitutes a “premium” expensive brand versus a “normal” midrange brand, premium sales are far more robust worldwide. Koenig said that this is about consumers seeking a higher-quality experience—not a hard argument to make here in TidBITS with an audience of Apple customers. But I suspect other factors are in play, and you might agree if you share my cynical view that more expensive devices are not always better.

Put simply, there have been many winners and losers in the pandemic economy, and some people who have disposable income have much more of it now, while other people have had their income completely disrupted. I suspect that worldwide, it might be that if someone has the money to spend on technology at all, they have enough to buy premium brands for their prestige factor alone—leaving a much smaller budget sector and hence much flatter sales for technology competing on price. That’s bad news for companies selling commodity tech, but it’s very good news for innovators, cutting-edge R&D products, and design influencers, whose products hit the market with stiff premiums. It’s healthy for technology to have those high-risk sectors well-supported; this year’s cutting-edge is 2027’s mainstream.

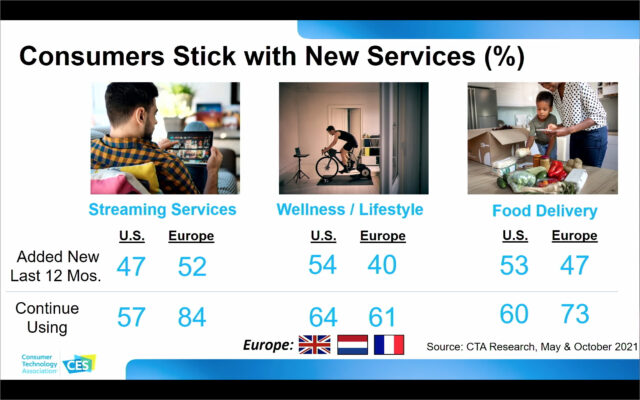

The other bright spot is that people who adopt new services and software tend to stick with their categories. Most likely, you might have tried several streaming services and abandoned a few once you decided what mix of shows you want to watch, but you didn’t stop paying for streaming services entirely. This is also true for fitness technology and food delivery services, both of which saw a major bump during the pandemic that isn’t likely to go away.

And I can attest, in other areas. I no longer pay attention to which of my Mac apps are licensed through Setapp (see “Setapp Offers Numerous Mac Apps for One Monthly Subscription Fee,” 25 January 2017), and I only noticed during the brief period I was transitioning from a MacBook Pro to a new M1-based MacBook Air since my subscription only allowed those apps on a single Mac. This kind of invisibility, where the service subscription fee is seen as a sunk cost and the service itself becomes intrinsically integrated into particular hardware, guarantees recurring revenues for those companies.

You Have Nothing to Lose But Your Supply Chains

Even the best technology in the world won’t do you any good if you can’t get it at any price. It’s not just about whether there’s a microchip available for your new truck; as with my decision not to go to Las Vegas, it’s also about whether there’s a sufficient workforce to plug in that chip (or keep planes in the air).

There’s remarkable fragility in the interwoven web of commerce that fuels modern society. The pandemic disrupted both the production of new widgets and our ability to get them where they were needed. Many people only became aware of the global shipping industry when a very large ship took a very bad turn in March 2021, but the fact is that a frighteningly large portion of our economy rests on our ability to get things where they’re needed at the time they’re needed. Remove some of the workforce necessary on docks and ships due to illness, and those disruptions ripple both up and down the supply chain. Of course, the same problem can occur in factories. In the case of microchips, in late 2020, it took 12 weeks for a commercial-size order to arrive; a year later, that delay had increased to 22 weeks.

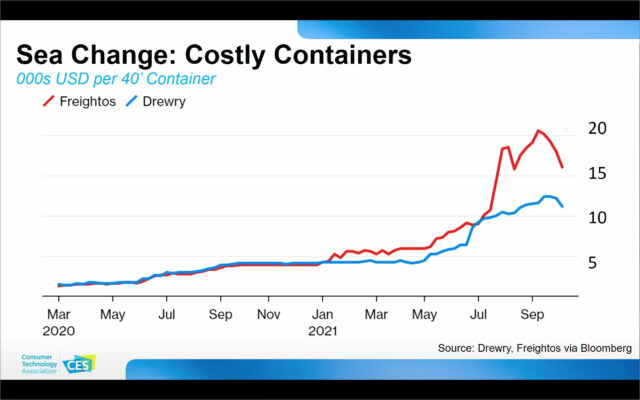

Meanwhile, the price you’re paying in stores is frequently based on what has in the past been negligible per-item shipping costs. Those costs are much less negligible these days, as part of the driver for the current rate of global inflation is a doubling or tripling of the cost to move a giant metal box of widgets across oceans.

Koenig said that while the shipping cost problem was unlikely to change soon, he expected that other issues would be resolved by adding new technologies to the problem at the enterprise level. But then he disturbingly referred to using autonomous trucks instead of drivers, or robots instead of humans in factories. These ideas aren’t necessarily problematic in and of themselves—indeed, in the long run, they’re almost a certainty.

But are they something we should look to as a quick solution to our current problems? There are 3.5 million truckers in the United States alone, supporting many other industries (think of every roadside motel, restaurant, and small-town economy near a highway). We may indeed have the technological capability to switch to self-driving vehicles in a few years (according to what I’ve heard at CES and elsewhere over the last decade or two), and it’s likely true that there will be major economic benefits when human driving becomes a hobby that isn’t allowed in cities or on interstate highways. (If you think that’s disruptive, keep in mind that the technology that cars replaced was 6000 years old.) But it will likely be a decade or two before we have the political and social will to take humans literally out of the driver’s seat.

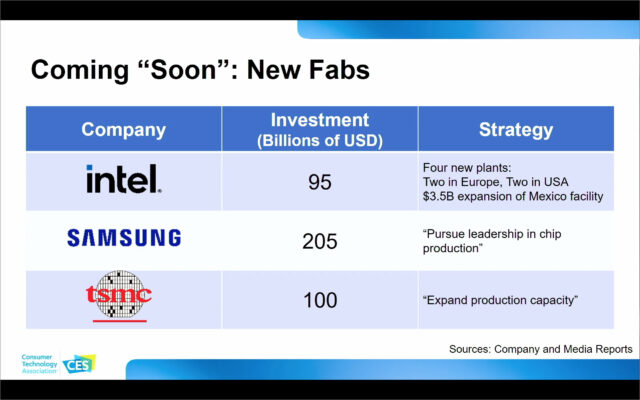

The more reliable solution, which is also being pursued, is to improve manufacturing capacity and factor shipping disruptions into future supply chain planning. The microchip deficit won’t be solved quickly, but three major chip fabricators—Intel, Samsung, and TSMC (the manufacturer of Apple’s M1 chip series)—have announced a total of $400 billion in investments in new factories, contributing to a total expected increase in manufacturing capacity of 16% in 2022. Better still, some of these factories will be spread out globally—as opposed to the current situation where 75% of fabs are located in East Asia. The current situation leaves us all vulnerable to a single large disaster that could take out multiple factories at once. This has happened in the past, as the one-two punch of 2011’s earthquake and tsunami in Japan and later flooding in Thailand impacted the supply of RAM chips and hard drives, respectively.

I Met a Verse I Didn’t Like

The presentation moved on to augmented reality and virtual reality (AR and VR), a perennial CES topic that has grouped both technologies under the term XR until this year. Virtual reality is what you might expect: the experience of putting on goggles or a head-spanning headset and being presented with a completely different reality, such as a video game or a walkthrough of a store distant from where you are now. Augmented reality is different: it takes information from your physical environment and overlays new information on top of it while still showing you your surroundings. Good examples of augmented reality include Google Live Street View, which shows arrows pointing in the right direction levitating in mid-air over the street, and Pokémon Go, a once-ubiquitous and still quite popular game where you can see critters showing up on your phone that—despite the illustration below—are decidedly not in your backyard.

Proponents of AR—of which I am one—expect that the technology that will make it ubiquitous is some kind of unobtrusive headgear that shows you an augmented picture of your surroundings without making you look like you just beamed in from the Enterprise. Such a device doesn’t yet exist for either AR or VR. VR devices like the Oculus Quest 2 headset are laudable for what they can do in smaller packages than in the past, but they are decidedly not unobtrusive. Still, as with most years at CES, even a cursory review of exhibitors reveals a raft of small companies that promise a lightweight glasses-only XR future—just as soon as a major manufacturer licenses their technology for several years of development. Despite this lack of hardware, Koenig said that the “basic building blocks” of XR are available: mobile devices with CPUs that can handle the calculations in real-time, haptics to give feedback other than audiovisual, and 5G (presumably to allow for a future when XR content is sent by devices other than the one in your pocket).

Disturbingly, at no time did Koenig use the term XR. Instead, he referred to this collective group of technologies as the “metaverse,” a term which most of us heard for the first time when Facebook changed its corporate name to Meta. Apparently, the CTA is another organization that wants the metaverse to become the accepted term for all extended reality experiences because Koenig simply used the word without explaining or defining it, as if it was already generally accepted by the audience. (The Verge has a particularly amusing and cynical Q&A about the metaverse that shows just how amorphous the concept remains.)

I find this troubling for two reasons. The first is that it’s inaccurate: the prefix “meta” means that what follows is about something else. The metadata for a file on your Mac includes its last-modified date and its size in megabytes; it’s data about data. Virtual reality isn’t about your local reality; it’s a temporary replacement for it. Augmented reality can be metadata—such as a heads-up display of the temperature where you’re standing—but it’s more likely an overlay of information not directly derived from your surroundings. The name of the restaurant you’re looking at might be considered metadata; a Pokémon Go critter fluttering outside is not.

This distinction between metadata and overlay data might seem pedantic, but it becomes profound when you consider that metadata is essentially optional, whereas overlay data is essentially… essential. The more society and the economy start moving experiences into an augmented realm that requires overlay data, the more people will be left out if they can’t afford or don’t want the necessary technology to access it. Have you been to a restaurant with QR codes on the tables, where all the ordering is online? This pandemic adaptation, common in my area, makes it harder to eat out without a charged phone and adds a technological layer to what was previously a purely social process. It’s an existing example of what could happen when augmented reality becomes common and requires expensive gear. Koenig said that the experience of the metaverse will become “inextricably” linked with physical reality. I think he’s right, and I think it will operate in both directions—miss out on the extended reality of your surroundings, and you’ll miss out on key aspects of your society.

“Metaverse” is a rebranding of something for which we already had terms: XR most recently but also dating back to 1982 with the word “cyberspace” in William Gibson’s Neuromancer. “Metaverse” itself is also an old word, dating back to 1992’s Snow Crash by Neal Stephenson, but it never entered the mainstream like cyberspace. Typically, corporations promote new words when we already have perfectly cromulent ones because they want to own them. Cyberspace and XR are virtual places where community and public spaces might exist; a metaverse is intellectual property where communities are owned, like on Facebook. When a $925 billion company changes its name to make you associate it more with a technology space that’s still years off, that’s not done lightly—and it’s not done without investing in the idea that Meta, Inc. is going to own a metaverse in the same way that Facebook owns a public square with 2 billion inhabitants.

Pardon me for possibly sounding utopian, but in my view, it’s crucial for a society to have public spaces uncontrolled by commercial entities. The Internet became what it is only because no one owned it, which inspired thousands of companies and open-source programmers to create an interoperable cyberspace that could be extended and inhabited by anyone else. To me, a future where multiple non-interoperable metaverses are instantiations of intellectual property is dystopian—will the experience of visiting Facebook Paris be radically different from Google Paris and Apple Paris, or just plain unmediated Paris? That’s certainly possible.

If you think I’m reading quite a lot into a single word, consider that Koenig wasn’t just selling metaverses; he also said that “crypto[currency] is the coin of the meta realm.” There was no other data to substantiate this extraordinary claim. Even if you’re an investor in Bitcoin or some of its thousands of competitors, it’s quite unlikely you’ve used any in commerce. As I write this, the value of a Bitcoin has dropped 3.2% today and 11.8% in the past week, while being up 23.1% overall in the last six months. That’s a highly volatile currency of a terrifying economy, possibly based on Dutch tulips, and while it might be fun to visit, I wouldn’t want to live there.

There was one thing Koenig said about the metaverse that I agree with: “We’ll be talking about this for the next 20 years.” Yes, and I hope that’s long enough for us to come to some agreement about how this technology can change our societies before we adopt it wholesale.

This Year’s Future Is the Same as Last Year’s

Otherwise, Koenig’s presentation said many things familiar to annual attendees of Tech Trends, which is to say, the future wasn’t here last year and it’s not yet here now. 5G communications are the “connective tissue” for the next decade, just as they were last year. What’s potentially new is that in 2022, the 3GPP working group will be coming out with a new set of requirements for 5G that will add additional standards for the industry. That’s unlikely to affect you directly, but it could help Koenig’s assertion that 5G will be revolutionary for how enterprises do business, both with each other and internally.

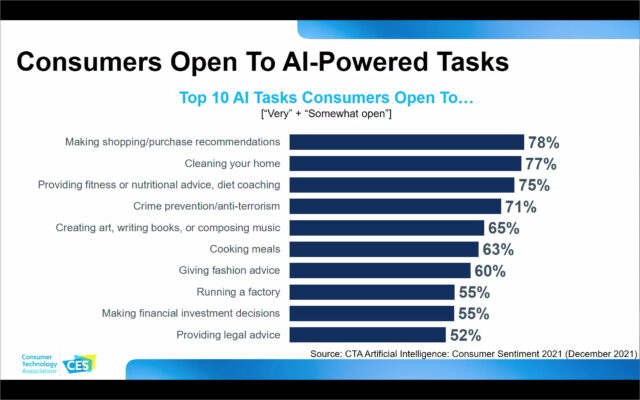

Artificial intelligence is such a CES regular that even Koenig called it a “perennial.” Even so, I was intrigued by CTA’s study about what tasks consumers would be willing to have performed by AI. The data describes a population that is, in my view, deeply uninformed about the risks and rewards of AI technology. At a Yale forum on ethics in AI that I attended recently, experts argued that AI must only be supportive of key decision processes, with the ultimate arbiters remaining human. Compare that with a population that’s apparently open to allowing AI to make investment and counterterrorism decisions rather than recommendations (although people do make this distinction in the very important realm of shopping).

One potential example of this missing risk assessment might be in the highlighted example of John Deere’s new See and Spray Select AI technology, which targets weeds in farm fields selectively, lowering the use of pesticides by over 75%. This sounds like an unmitigated win, but I’m curious to know how well secondary impacts have been studied, including how this might affect farmers who already can’t repair the tractors they depend upon. A country that makes counterterrorism surveillance and arrests dependent on AI may find itself taking actions inimical to its values; likewise, an investor who prefers a safer buy-and-hold strategy of index funds may be unpleasantly surprised to discover that their AI has decided to get into day-trading.

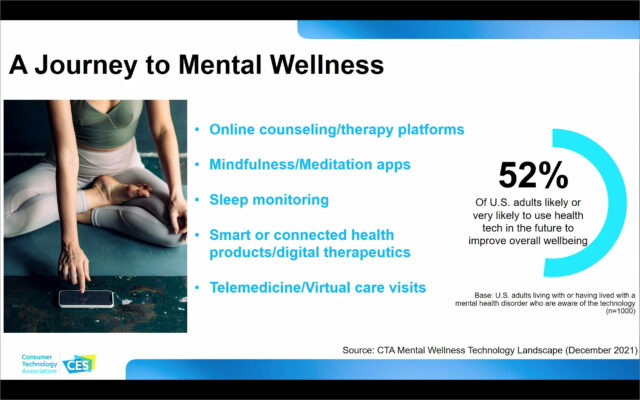

In other news, this year’s future is the same as last year’s, and readers seeking details about upcoming changes in space technology, transportation, sustainable technologies, and digital health will be better served by my past coverage of Tech Trends events than by coverage of this year’s events, which provided few details. One interesting exception: documentation of a possible future trend where people are more comfortable using technology to improve their mental health. Over half of respondents who live with or have had a mental illness say they’re willing to adopt such measures. In a country where there’s a shortage of mental health professionals, and with the pandemic making stress and depression a more common occurrence, the use of technology to prevent milder cases from becoming worse seems like a positive step.

Tune in again next year, when we’ll see what the CTA both thinks and is promoting as the next set of trends. Here’s hoping that the pandemic will have subsided enough by then to make physical attendance saner and safer.

Meanwhile, when are 16K see-through OLED televisions coming?

/s

Previously, my understanding was that Microsoft had been saying “the metaverse,” implying a single interoperable one. Now it seems that the company is going in the other direction, as per this quote:

I am very, very dubious about the metaverse concept. Or, more accurately, I’m very, very dubious about the reality of what might somehow be considered a metaverse. Conceptually, it’s fine as (dystopian) science fiction—fine, go read Snow Crash and Ready Player One. But in reality? O don’t trust any of today’s tech giants to create something that (a) won’t suck and (b) won’t be utterly exploitive. Apple probably has the best chance since it would be mostly content to make money on the hardware and subscription fees and in-system sales, whereas the rest would likely focus on advertising, especially since they could know exactly what you would be doing in-metaverse at all times.

I couldn’t tell if this was tongue-in-cheek, but from everything I’ve heard (admittedly not as an insider in the field), that seems massively optimistic (or pessimistic, depending on your point of view). It’s not yet possible to have safe self-driving cars in a limited, bounded, highly-mapped area. I think we’re a long way off from HGVs driving themselves door-to-door across random areas, without being mass killing machines.

I follow this world pretty closely, largely through the eyes of Brad Templeton, and while it’s definitely going to be more than a couple of years, some things are moving pretty quickly. The sudden interest in electric vehicles is something that wasn’t expected as well, and once robocars get to some level of good-enough, it’s possible adoption will happen quickly. People are really interested in the Tesla Full Self Driving beta, which is, from everything I’ve seen, truly terrible. Nowhere near what Waymo is doing in Arizona, for instance.

From what I’ve read, there’s little likelihood of robocars being dangerous to people; when they fail, they’ll fail in terms of being too start-and-stop to ride in or slowing down traffic by not being sufficiently decisive.

Apple Accelerates Work on Car Project, Aiming for Fully Autonomous Vehicle

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-11-18/apple-accelerates-work-on-car-aims-for-fully-autonomous-vehicle

Apple shares hit record after report says the company wants to build self-driving car as soon as 2025

Apple’s Mystery Self-Driving Car Tech Covered 13,000 Miles Last Year

Apple’s Project Titan has been running full steam ahead on developing autonomous cars for years, and I’ll bet they are also thinking about other autonomous vehicles. “Changing the world” is Apple’s big thing. They already have their own battery, chip, mapping, etc. expertise and manufacturing capabilities. They were reportedly negotiating with car manufacturers about a partnership for a while, but it looks like they decided to go on their own.

What’s different about Apple’s efforts is that they are not blabbing incessantly about what they are going to to build to the press like Elon Musk, Mark Zuckerberg, etc. do. Like iPod, iPhone, Watch, SE30, etc., etc. Instead, Apple slyly builds anticipation for their new products and services, but reserves the details and fine points for a big reveal.

Google has also had a not very secret autonomous vehicle in the works for years.