Understand Cryptocurrency, but Don’t Invest in It

Cryptocurrency is on everyone’s lips, but it should be in no one’s virtual pockets. An overhyped form of imaginary value storage, it has all the disadvantages of cash, suffers from all the volatility of an overhyped penny stock, and consumes more power than a mid-sized European nation. Although it has been vaunted as untraceable, anonymous, and beyond the reach of governments, none of that is true. Law enforcement agencies have used cryptocurrency to take down crime rings, stop people from exchanging child sexual abuse material, and seize massive amounts of Bitcoin and other currencies.

At one point, I thought cryptocurrency might be among the most exciting and important innovations in technology and finance. It felt as though it had a transformative power in transcending national boundaries, providing a measure of personal independence outside of that offered even in democratically run countries, and disconnecting value and ownership from greedy, predatory, and sometimes corrupt financial institutions.

Over several years, my thinking has evolved to a provisionally cynical position. As I’ll discuss, none of the promises and benefits of cryptocurrency have materialized. Instead, the field has devolved into hype and scams, with the most avid participants—whether fraudsters or true believers—just trying to get as many people as possible to pump real money into digital currency. The phrase “digital Ponzi scheme” crops up a lot.

My overriding advice right now is, “Don’t buy cryptocurrency.” No existing cryptocurrency systems provide investing, hedging, or other financial benefits worth engaging with compared to existing financial instruments and markets.

But I say I’m “provisionally cynical” because, despite all that is wrong with the current systems, I urge you to learn as much as you can about cryptocurrency’s underlying principles. Some portion of what we see today will migrate into mainstream finance. That will include activities as broad as sending money to a friend, making certain retail and online purchases, investing in stocks, raising money for projects, and even buying a house. All of these could be wrapped up in immutable, verifiable transaction records.

It might seem contradictory to say you should avoid engaging in cryptocurrency while becoming a student of it. But that could apply to any dangerous or risky endeavor you want to learn more about safely.

Within a few years, more than one government will issue an official form of cryptocurrency, likely including the United States; China is already underway with a digital renminbi. In addition to financial records currently managed by government entities like county clerks, permanent ledgers will appear that record details of sales, purchases, and other exchanges of value that require an auditable record.

Private companies, non-profit organizations, and government bodies will likely create ways to participate in decision-making by establishing a cryptographically verifiable stake of value that also gives you voting rights or other involvement in governance. This is akin to stock ownership but with fewer intermediaries preventing you from exercising your opinion.

None of the above is techno-futurism or hype. It all exists today in some form, albeit in examples that are often shaky, unreliable, mismanaged, fraudulent, or intended for Big Brother-like oversight. Bitcoin may eventually fade away—much like once-popular technologies like Gopher and FTP did—but cryptocurrency will survive. A massive percentage of today’s transactions already occur electronically but in such a haphazard and unverifiable way that we need something better.

We’re migrating to a situation where people need to differentiate between public, speculative projects that are far too risky—or simply corrupt from the start—and valid projects based on low-carbon, reasonably scalable private and governmental blockchains used for discrete purposes.

(I learned a lot of the nitty-gritty about cryptocurrency when researching and revising my book, Take Control of Cryptocurrency, which delves into cryptocurrency topics at greater length.)

Understanding Cryptocurrency Basics

I constantly wrestle with how to explain cryptocurrency to the uninitiated because it involves aspects that cross the boundaries of other kinds of financial instruments, like cash, debit cards, and stocks, as well as those that have no analog in everyday life.

Here’s a gloss on how cryptocurrency is like—and unlike—things we all know:

- Paper currency: Each cryptocurrency unit is uniquely numbered like paper money. It can pass between hands without help from a financial institution. The unit value is denominated as part of its nature. Transactions are quasi-anonymous: it’s hard, but not impossible, to trace the flow of value from one party to the next, at least for law enforcement when large amounts are involved. But cryptocurrency isn’t like paper money because you have to pass it through an online system. Plus, some cryptocurrencies, like Bitcoin, are highly volatile, unlike cash in most modern societies.

- Debit-card transaction: When you use a cryptocurrency, you’re always sending money; there’s no invoice, billing, or debiting process. This makes it somewhat like using a debit card—an electronic transaction that comes out of your stored value (your savings) held on a ledger somewhere (your bank’s records) that’s sent in a way the recipient can verify as legitimate. Yet, cryptocurrency’s “ledger” isn’t stored in a central location like a bank—it’s a distributed consensus that agrees on what transactions have occurred, so there’s no one to complain to if something goes wrong.

- Stock ownership: In many ways, cryptocurrencies are like stocks. Owning shares in a company lets you ride the tide of a combination of the firm’s real value and sentiment about its future earnings. For a company in turbulent times or around which rumors swirl, the price of shares can zigzag up and down. The stock can be exchanged for currency through intermediaries and vice versa. Cryptocurrency shares the volatility of stocks but doesn’t reflect any underlying fundamentals, just market perception. And unlike stock, no “company” exists whose value and performance are reflected in the “shares.”

- A password: At its heart, cryptocurrency relies on knowing secrets. Proving ownership or spending any chunk of crypto coin requires an encryption key that only you possess. But unlike a password used to unlock a computer or online account, you don’t gain access to anything with the key—you only use it for proof. All your ownership comes from that proof.

So with that in mind, what is cryptocurrency itself? Although it might take some advanced study to truly understand it, I can explain the basics in a few sentences. Cryptocurrency is a financial instrument that uses cryptography instead of other methods (like physical possession or traditional financial institution database entries) to verify ownership. When you purchase cryptocurrency, the transaction is written into a permanent, distributed ledger—a blockchain—that uses cryptographic algorithms to render the records permanent, unchangeable, public, and verifiable by any party.

As fully decentralized systems, cryptocurrencies don’t need a government or other single entity to issue units. Instead, cryptocurrencies rely on a consensus mechanism that lets participants bypass trusting any individual or organization. The blockchain contains the “truth”—you de facto don’t own that cryptocurrency if your record of ownership isn’t in the ledger, if you can’t produce a private encryption key related to your ownership (the classic “lost key” scenario), or if the transaction can’t be verified. It’s like having a bank account with a balance you can’t access—ever. Because there’s no central authority managing a cryptocurrency, there’s no one to complain to in the way you might dispute a charge with your credit card company or force a bank to release your savings account through a court action.

How Bitcoin Works

Here are the four major parts of Bitcoin, the highest valued cryptocurrency by far:

- A group of people (miners) voluntarily compete over short periods of time, about ten minutes, to solve a mathematical needle-in-the-haystack puzzle. The miner who solves the puzzle first is the winner and receives a chunk of Bitcoin. Only one miner is successful for each block; all other effort is discarded. The puzzle resets, and the contest begins again. Most mining is done by a handful of heavily invested mining companies.

- A network of peer-to-peer, independently operated software servers (nodes) exchange information about transactions waiting to be recorded, recently solved puzzles, and the state of the network and system.

- Sets of transactions are tied together cryptographically through mining (blocks). A miner creates a block when they solve a mining puzzle and broadcast their solution to nodes.

- An immutable ledger of all completed transactions (blockchain) grows by one block of new entries each time the mining puzzle is solved and accepted by nodes.

One way to understand how Bitcoin works in practice is to compare a Bitcoin payment with a purchase made using a chip-based card or mobile payment system like Apple Pay. Here’s how that card-based transaction proceeds:

- When prompted to pay (either in person or via mobile payment in a browser or app), your card or mobile device performs a cryptographic handshake across a network to validate the payment and create a unique set of information that the payment network accepts. Your possession of the card (in person) or a biometric approval (like Face ID) makes the transaction legitimate.

- The merchant receives a digital acknowledgment that a payment was made.

- In a ledger maintained by the payment system, the transaction amount is debited from your record. Either it’s applied as a charge on a credit card ledger maintained by your credit card issuer, or it’s debited against your bank account and transferred as an electronic record through the payment network as a credit on the seller’s merchant account.

- Fees are collected in various ways across the system, typically from the merchant, and paid out in various amounts to the payment processor, payment network (like Visa or Discover), and merchant’s bank.

- If your payment is later declined, the merchant can complain to the payment network. If you have a problem with your purchase, you may be able to have the charge or debit reversed and refunded to you through your bank or credit card issuer.

With a Bitcoin payment, the process works similarly in total, but the actual set of actions is quite different:

- Get someone’s Bitcoin address. (Even ordinary people may have many.) It may be provided in several ways, including plain text or a QR code.

- Send them money via wallet software. The transaction requires a fee to encourage miners to consider including your transaction as part of their puzzle block. The wallet software essentially stores the encryption secrets you need to create a properly formatted transaction that proves your ownership and uploads that transaction to a node.

- The node broadcasts your transaction to other nodes in the network. Since it’s a peer-to-peer network, nodes are constantly receiving and broadcasting transactions.

- The transaction floats in a pool of all outstanding transactions until various miners’ software decides the fee justifies including your transaction in their attempts to solve the puzzle.

- A miner whose transaction payload includes your transaction solves the puzzle and distributes a block with the transaction baked in.

- Other nodes independently validate that block and add it to their copy of the blockchain.

- The recipient can validate that the transaction has been added to the blockchain by examining recent entries on the blockchain. Wallet software automates this.

New units of Bitcoin can be created only by miners, and only a limited amount of Bitcoin can ever be created. That amount left halves about every four years. The current reward is 6.25 Bitcoin per block. You can divide Bitcoin units down to tiny units called Satoshis, which are one-hundred-billionth of a Bitcoin. For example, $5 is roughly equivalent to 0.000124 Bitcoin or 12453.05 Satoshis.

Miners can then use those Bitcoin units to pay others in Bitcoin or cash out through cryptocurrency exchanges. These exchanges provide crucial liquidity for Bitcoin markets. Without parties willing to trade Bitcoin for other cryptocurrencies and government currency, Bitcoin would be an entirely closed system. Exchanges bear the risk of holding and trading cryptocurrency. They have to determine what price they will pay or charge for Bitcoin based on their own algorithms and monitoring prices paid at other exchanges. Cryptocurrency exchanges are similar to international currency exchanges, earning a fee as part of these conversions. When many people want to buy Bitcoin, the price may climb rapidly, but there’s a lot of Bitcoin to sell. Conversely, when people want dollars for Bitcoin, the price can plummet as exchanges hold relatively limited amounts of hard currency compared to conventional banks or central government banks.

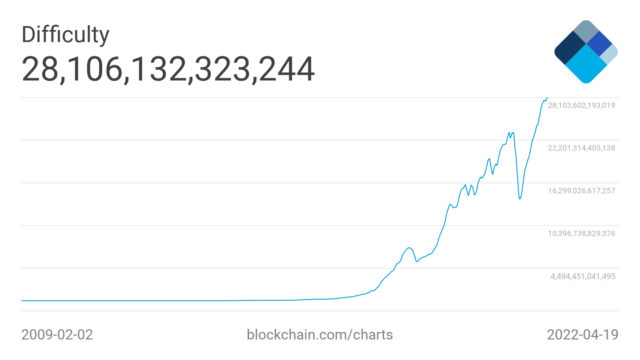

The Bitcoin algorithm provides a mechanism to keep block production on a cadence of about one every 10 minutes. That rate prevents the peer-to-peer network from being overwhelmed while also providing time for transactions to “cure”—to be in the blockchain long enough to be securely locked in place. (This helps protect against the 51% attack described below under immutability.) As miners add computational capacity, the Bitcoin system resets the difficulty of the puzzles they have to solve every few days. The additional computational speed is effectively offset by the difficulty factor, resetting it back to the 10-minute cadence. This method of requiring some weighted amount of effort is called proof-of-work, and it’s the basis of trust as it can’t be faked. Only hard work can solve the puzzle—there’s no shortcut.

Constantly adjusted difficulty requires miners to invest in faster equipment lest their competitors begin to earn more rewards. This strategy burns more and more power in a Red Queen’s race to get almost nowhere: the outcome is the same, but the electrical consumption and environmental cost increase in step with the difficulty. Mining makes economic sense only as long as the miners’ cost of equipment, facilities, and power remains, on average, lower than the value of the Bitcoin they earn as rewards.

Occasionally a blip occurs—such as a sudden drop in Bitcoin’s price or Chinese authorities banning mining—that reduces the profitability and takes mining capacity offline. In those cases, the difficulty resets to a lower level. But the strong trend is for the difficulty to increase over time.

Ethereum and NFTs

Bitcoin’s younger sibling is Ethereum (its currency is Ether). One Ether is worth about 8% of a single Bitcoin, and cryptocurrency exchanges value the full market value of the outstanding Ether at about half that of Bitcoin. Unlike Bitcoin, Ethereum wasn’t created as a replacement for cash, nor does it have a limit on the maximum amount of Ether that can be mined. The Ethereum network can perform simple transfers of value, and that’s its most frequent use.

But its power lies in smart contracts, network-based programs that run when they receive an input. They’re like tiny virtual software containers. Smart contracts can allow complicated rules for taking an incoming payment and splitting it up, but they can also be used for more sophisticated purposes. That includes decentralized autonomous organizations (DAOs), groups that set up smart contracts that define ownership, voting, and the consequences of votes—a nice idea, but such groups exist largely outside existing regulatory structures. That can cause problems when they fall afoul of fraud, attacks, and mismanagement. Ethereum also supports distributed apps (dApps), which remain in an experimental stage: they allow the use of the Ethereum network as a general-purpose distributed computer.

Ethereum also enabled one more element you should know about because they have been so omnipresent in the media: NFTs, or non-fungible tokens. NFTs are also entries on a blockchain but are formatted in a special manner that allows them to be created without an associated currency-style value. An NFT is effectively a serialized token with its uniqueness established by residing on the blockchain—like a signed baseball card or a ticket to a concert.

To explain, a fungible asset is one that’s identical to all others of its class: any dollar in one bank account is the same as any dollar in another. In contrast, a non-fungible item can’t be exchanged like for like. In the real world, non-fungible items include original works of art, real estate, and unique collectibles.

An NFT doesn’t confer ownership of an underlying asset, like a copyright, licensing permission, or possession of a physical object. It’s just a pointer that points to a URL. Once set, that URL can never be changed because NFTs are immutable. This is why people joke about “right-clicking to steal” NFTs: most NFTs point to images hosted on publicly available Web pages that can be downloaded locally by right-clicking and choosing Save Image As.

Bitcoin can’t host NFTs because it’s not “programmable,” so many NFTs are based on Ethereum. However, there are also now cryptocurrencies created solely to issue NFTs. As tokens, NFTs can be sold for arbitrary values. They aren’t fixed, like units of cryptocurrency.

The most reported-on use of NFTs is making iterative pictures of ugly graphics, like apes and lions. That’s the least interesting use, however, as NFTs could provide both verifiable uniqueness for all sorts of things and transferable ownership.

With those basics out of the way, let’s look at the myths of cryptocurrency and then see where it’s headed.

The Myths of Cryptocurrency

People who are cryptocurrency advocates or promoters tend to gloss over or ignore its drawbacks. You can hear them and more credulous tech writers recite a litany of cryptocurrency benefits:

- It’s anonymous.

- It’s untraceable.

- It’s decentralized.

- It’s immutable.

- Immutability is good.

- It’s anti-inflationary.

- It always appreciates in value.

- Transactions are cheaper than credit cards.

- It’s removed from governmental control.

- The environmental problems will be solved.

- It’s safe.

- It’s simple.

I could write even more thousands of words explaining why all of those are misguided, false, exaggerations, or require footnotes and provisos. Let’s see if I can instead knock them off in a few paragraphs.

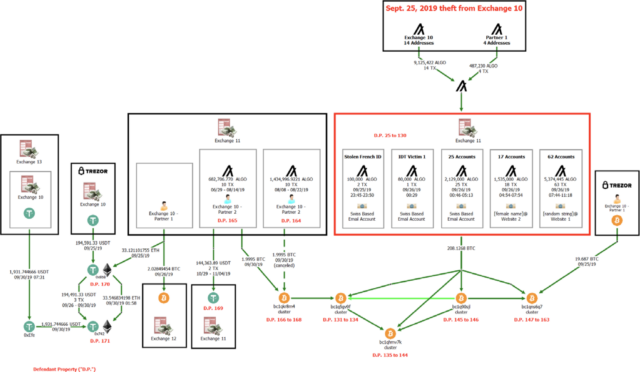

It’s anonymous. It’s untraceable. Cryptocurrency transactions rely on a public blockchain that everyone can see and validate independently. This is part of the basis of decentralized trust: you don’t have to believe anyone; just check the cryptographically consistent record. As a result, you can trace transactions over time as they move between addresses. Companies like Chainalysis specialize in this. It’s better to say that Bitcoin and other major cryptocurrencies are pseudonymous: identity and address are separate things but can be associated. (A few cryptocurrencies, like Monero, offer something much closer to irreversible anonymity, but their transactions are a tiny fraction of all those conducted.)

It’s immutable. It’s decentralized. The blockchain is designed to be immutable, but that relies on true decentralization of mining. Any time at least 51% of the computational power across the entire mining network is controlled by a single entity or back-room deal, the chain could be reversed by a few too many blocks depending on the amount of computation. It could allow double-spending, in which units of cryptocurrency appear in a block that becomes invalid but which the receiving party has already acted on (like releasing a real-world escrow or transferring ownership of a digital asset). Such a cabal could even prevent others from having their transactions written to the blockchain. This isn’t theoretical; it has happened several times.

Many cryptocurrencies and seemingly nearly all NFT projects have a high degree of central ownership: one or a few parties control the entire system and the direction it takes. Even when a larger group of people are involved, a small minority that controls the majority can have effective control. For instance, following a huge DAO meltdown in 2016 that would have cost participants the equivalent of $150 million, the core Ethereum group, the Ethereum Foundation, stepped in to rewrite Ethereum’s rules to annul the theft. This resulted in a hard fork of Ethereum, resulting in the Ethereum Classic spin-off created by miners who disagreed with the move. Even with wallets, software that manages ownership and sales, consolidation among vendors can lead to a situation where an immutable entry simply doesn’t appear because the wallet developer blocks it.

Immutability is good. You could argue that, in general cases, blockchains are immutable. But is that always good? Immutability is overrated in one sense. When you make a credit card purchase, you have a variety of protections under the rules of the card, the card’s issuing bank, and your state or regional or national government. Credit card transactions aren’t immutable, and thus they can be reversed to respond to fraud, misrepresentation, or other reasons. (Banks may hold balances or require reserves to cover reversed transactions.) Cryptocurrency transactions would largely sidestep such protections.

Also, blockchains can store or point to all sorts of data. Future blockchains may have the spare capacity to encode large amounts of data, such as complete legal contracts, media, and software source code. So what happens when CSAM, “revenge porn,” deeply personal details, and stolen software are permanently encoded into blockchains? For some categories of harm, the blockchain might be effectively illegal to possess on your computer or even view parts of—it simply hasn’t been adjudicated.

It’s anti-inflationary. It always appreciates in value. At one point, economic/political promoters of cryptocurrency liked to assert that Bitcoin and others would resist inflation. As inflation rises, currencies devalue relative to what they can purchase. Cryptocurrencies were supposed to counter that by having a rising exchange rate with real-world currencies to offset devaluation. It was a tricky point to make in the middle of one of the lowest periods of inflation across established economies in global economic history. And it hasn’t happened as inflation has increased in the last year. Instead, cryptocurrency has generally been so volatile, with huge spikes and drops multiple times since 2019, that it’s hard to draw any conclusion.

Internally, Bitcoin and Ethereum try to restrict the growth of their basic units. Bitcoin was created with a finite number of coins; Ethereum is unlimited but implemented a change in August 2021 to “burn” (permanently destroy the value of) Ether with every transaction relative to its complexity to prevent the deflationary effect of constant growth of Ether.

Transactions are cheaper than credit cards. A selling point of Bitcoin in its earlier days was that it would cost fractional US cents to carry out a transaction compared to the roughly 3% that credit cards eat up. It would enable micro-transactions, letting you send pennies to pay bloggers and dollars to pay musicians. That didn’t last.

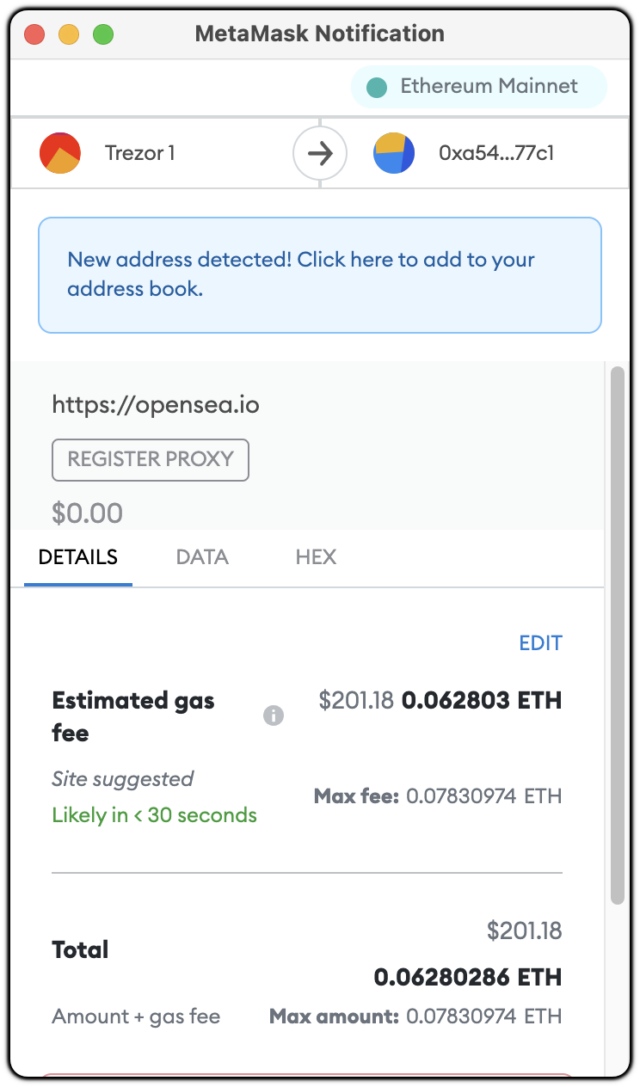

Because Bitcoin and Ethereum can handle only a modest number of transactions per minute, the fee paid to miners becomes a huge component of having transactions written to the blockchain. This pressure caused the cost of Ethereum transactions to rise to tens of dollars in 2021, regardless of the size of the transaction. Bitcoin fees have remained lower but can still average several dollars. (Some attempts to increase the transactions-per-second rate involve layering other blockchains on top of existing cryptocurrencies. However, building a robust infrastructure on top of unstable foundations comes with many risks.)

On top of that, Ethereum has gas fees that are tied to the cost of executing a transaction, since all Ethereum transactions equate to programs that consume computational resources. Complicated smart contracts can require huge amounts of gas compared to a simple value transfer. These gas fees can become astronomical—much higher than the actual amount being transferred. Plus, you can’t accurately predict how much gas a transaction will require. If your wallet transmits the transaction without enough gas, you forfeit the gas fee and your transaction isn’t added to a block. The worst of both worlds! (The workaround is to send too much gas, after which the extra is refunded along with the output of a transaction. Previously, gas used to be paid to miners but has been burned since August 2021, as noted above.

This has resulted in an absurd situation where refunds from a failed collaborative project to buy a copy of the Declaration of Independence cost participants more than their initial contribution. Such scenarios are common.

The environmental problems will be solved. Cryptocurrency remains an environmental disaster of the highest order. Bitcoin burns electricity equivalent to the requirements of a modest-sized European country to no good end: the value per Bitcoin doesn’t match the amount of energy required to mine it. Mining a single Bitcoin could require 1 watt or 1 gigawatt of power. For practical purposes, the cost of mining produces an effective ceiling due to capital costs, operating expenses, and power usage. Miners try to stay in the black by mining more Bitcoin than their costs. However, if Bitcoin skyrocketed to ten times its current purchasing power, miners would fight an upward race to find more power wherever they could. The credit card network is millions of times more efficient per transaction and scales incrementally instead of in lockstep as transactions increase—ten times the current volume doesn’t require ten times the current hardware or electrical use, as most of the investment is in basic infrastructure.

Because the vast majority of cryptocurrencies, led by Bitcoin and Ethereum, use algorithms that require particular computations, it’s possible to estimate how many operations are performed per second across the network. Digiconomist uses that and other data to estimate a range of about 80 to 320 terawatt-hours per year of use between Bitcoin and Ethereum. That’s somewhere between the amounts of electricity used by Belgium and the UK.

Miners also literally burn through hardware, resulting in shortages of chips used for more productive purposes and a massive flow of e-waste, most unrecyclable. Digiconomist estimates Bitcoin mining currently results in 34 kilotons (70 million pounds) of tossed gear per year, equivalent to the IT waste of the Netherlands.

Promoters regularly try to explain how cryptocurrency is en route to becoming “greener” in two ways. First, Ethereum may be nearing the end of a multi-year transition to Ethereum 2.0, an energy-efficient algorithm that scales well without a corresponding leap in resources. The new protocol relies on proof-of-stake, which validates new transactions based on people’s ownership of Ether rather than how much computational work they perform.

If Ethereum 2.0 is successful, about which there are grave doubts and major anxieties, it could reduce Ethereum’s energy consumption by 99% or more. Still, even at 100 times more efficient, it remains several orders of magnitude worse than, say, a Visa card charge. Promised years ago, the transition is always just a few months away. In fact, just days ago, the latest upcoming target for the transition was pushed to… a few months away.

Many crypto advocates argue that the mining world has a plan—already alleged to be somewhat underway—to transition to renewable resources, such that it will ultimately be emissions neutral. Instead of effectively mining Bitcoin from coal and natural gas, why not tap into solar and wind, or put a geothermal generator on a volcano? These are nice ideas, but the Earth is a closed system: there is no surplus renewable power generation equipment or naturally occurring, accessible sources of renewable energy. Skeptics call this greenwashing, in which noble reductions are trumpeted while the reality is much different.

Because only a finite amount of equipment can be made and put into service, any “non-productive use” (burning computation cycles for cryptocurrency) removes capacity from other purposes. Either miners buy a lot of solar and other equipment or output of renewable plants, just as they caused hardware shortages for GPUs and SSDs, forcing other generators to use dirtier power, or they keep using the dirtiest power as the rest of the world moves towards a less destructive approach.

It’s removed from governmental control. Earlier in this story, I noted how governments have become adept at tracing cryptocurrency and, more recently, at reclaiming it. The US Department of Justice seized $3.6 billion (8 February 2022 valuation) of Bitcoin connected to a major 2016 hack of the Bitfinex exchange. That’s the largest such seizure, but dozens of others have occurred, including $34 million from an alleged scammer in Florida by the U.S. government on 4 April, $25 million by the German government on 5 April, and an unclear amount of donations to those involved in occupying downtown Ottawa earlier this year. (Josh Centers wrote an elaborate analysis of crypto as a workaround to governments for his prepping-related publication, Unprepared.)

It’s safe. Advocates would like to tell you that it’s safe to invest in and possess cryptocurrency, but to rebut that point, I simply suggest you read through Molly White’s “Web3 is going just great” site, which is a seemingly endless feed of scams, rug pulls, hot potatoes, phishers, incompetents, and other old-timey frauds and business failures rendered anew. (Rug pulling is raising funds for a project and then taking those funds without delivering on the promises in fairly quick order. A hot potato is a coinage I may have come up with for finding the least savvy person to leave holding the bag—one without any money in it.)

It’s simple. If you’ve read this far, you’ll understand why this claim should elicit hysterical laughter.

Where Cryptocurrency Is Headed

How can I argue cryptocurrency is part of the future of financial systems when I’ve just told you how thoroughly pointless, broken, and fraud-ridden it is? Because it has a number of excellent ideas that could be expressed in more reliable, trustworthy, and useful ways. To achieve these goals, we need new cryptocurrencies that change some of the principles proven false in the idealized initial approaches.

- First, some elements of centralization could dramatically improve cryptographic-based transactions without putting any or all of it in the hands of governments, all while keeping identity secret without exaggerations about anonymity or privacy. Instead of trusting software developers and cryptocurrency creators—while claiming to trust no one—we would trust other entities that can be better vetted. The notion of complete decentralization was clearly a dream of idealists that, in practice, has proven as problematic as the worst cynics predicted: the control of most cryptocurrencies is in the hands of a few people who have accumulated lots of money. Ditto, anonymity, as I’ve noted throughout this article.

- Second, any new cryptocurrencies need to provide a way to cap and control transaction fees to keep them predictable and low, a claimed advantage that hasn’t proved to be the case in reality. Imagine a value-transfer system that was far cheaper than the credit card system, which averages around 3% in the US, and other more costly person-to-person and funds-transfer systems. Later cryptocurrency systems that learned from Bitcoin and Ethereum can carry far larger numbers of transactions, reducing pressure and enabling far cheaper transactions.

- Third, a key goal should be reducing fraud. Existing cryptocurrencies regularly suffer from exploitable weaknesses across the ecosystem—some fundamental in the protocols, some in wallet software, some in smart contracts, and some at consumer crypto-financial websites. For instance, as Cory Doctorow noted of smart contracts, they “don’t just create instability by being too complex to understand and vulnerable to coding errors–they’re also fraud magnets”; being immutable, they can’t be updated and require you to run a buggy program forever. The credit card system isn’t a paragon to compare to: it lost nearly $30 billion to fraud in 2020, a number expected to rise. Because a tightly controlled secret is at the heart of all cryptocurrencies, the possibility of reducing fraud and theft has a high upside for consumers, banks, and businesses.

- Fourth, a government-regulated cryptocurrency could make trans-border commerce easier without reducing accountability, fraud resistance, and protections against funding terrorism, laundering money, and engaging in financial crime. It’s typically slow and costly to send money between countries (outside of the European Union), particularly for smaller amounts. Economic migrants and cross-border workers may pay roughly 5% to 8% of what they send back to family in remittance fees, for instance, for over half a trillion dollars of transfers.

- Fifth, a future cryptocurrency could allow an organizational structure in which your stake gives you proportional voting rights in projects that aren’t publicly traded corporations. (Companies tend to have concentrated ownership and even separate classes of voting shares that dilute the effect of individual and small owners.) We can see this in effect already with decentralized autonomous organizations that use smart contracts that combine a purchase with a stake. A DAO ostensibly provides validated voting, a public record, and directly enforceable outcomes. The reality hasn’t matched up with the theory yet, but there might be a role for smart contracts in certain kinds of organizations.

One of the earliest examples of a more regulated, non-volatile, and perhaps government-backed cryptocurrency will likely be a stablecoin. A stablecoin is a cryptocurrency pegged to a fiat currency, like the dollar or euro. Existing stablecoins, like Tether’s USD, rely on managers who buy and sell assets to maintain holdings they claim are redeemable on a 1:1 basis between USD and actual US dollars. (Tether’s claims of reserve assets are highly disputed due to the company having over $80 billion in ostensible outstanding stablecoins; various parties have claimed that Tether can possess only a fraction of that in cash and short-term liquid securities.)

Current stablecoins don’t have their own blockchain but are built as special kinds of transactions on top of existing cryptocurrency blockchains, making them no better at avoiding underlying issues like environmental devastation and processing speed. Management is centralized at the top layer, as the stablecoin operator has to maintain assets and issue new stablecoin. However, once issued, stablecoin units can be as freely traded without central involvement as any other cryptocurrency.

Governments like the United States already use their own non-cryptographic ledgers to track electronic cash. The U.S. Federal Reserve said that for February 2022, out of $21.8 trillion in cash in the money supply, only about $2.2 trillion—roughly 10%—circulates as notes and coins.

What’s the difference between a US-managed stablecoin and the Federal Reserve’s record of cash? Cryptographic validity and transaction tracing. For some people, the former is highly desirable and the latter something they want to avoid out of principle; for governments, both could be useful. Transaction tracing is a key reason China is pushing forward with its digital renminbi.

A private or invitation-only blockchain could power a US Treasury stablecoin. Private blockchains in which stakeholders maintain trust internally have become increasingly popular. Given that the US government has never defaulted, it might be able to create and run a private blockchain to power a US Treasury stablecoin. You could also imagine a consortium of US credit unions given a charter to run a stablecoin to further their mission of extending banking, reducing fees, and providing fair mortgage and lending rates.

That stablecoin might not become available for years for ordinary people or uses. Instead, it might be a way to transfer value securely among institutions for their own purposes or for consumer and business needs. For instance, imagine buying a house. Instead of escrow, a stablecoin transaction would provide the security that money has changed hands with cryptographic assurance instead of a call or letter from a bank. (Or, for those who remember, a certified check in an obscenely large sum.)

Countries would need to update their laws to deal with the widespread use of cryptocurrency. For starters, laws need to change to deal with immutability when so much else about property can be adjudicated: a court might say money has to go from one place to another and enforce that through the banking system, but it would have no power over existing cryptocurrencies.

Yet, every time I need to send money to another person, pay for something online, or receive payment for goods I sell, it’s hard not to imagine that our creaky old financial system would benefit from a modern approach that uses encryption as a component of security and assurance.

It’s hard to say what the future of cryptocurrency will look like. In the meantime, I repeat my advice at the outset: watch and learn, but don’t invest.

If the above intrigued you, you can read much more about nearly every aspect of it in my book, Take Control of Cryptocurrency.

I think I agree with everything written (that I read). I didn’t make it half-way because it doesn’t directly involve me although I have heard plenty of recommendations to invest in it, even if they’ve tailed off recently. Cryptocurrency has been around a fairly long time now and the article confirms it still has a long way to go. The only part of it that interests me, when I want to finally spend the time, is understanding the cryptographic and technical aspects. However, I do not even know how our usual financial system works in that regard. I’m just glad it works as well as it does (which is quite good) given that Murphy’s Law otherwise applies to security on the internet.

There’s plenty I don’t understand about cryptocurrency. I can’t even get past this first step. Who issues the puzzles?

Also, I’m wondering why cryptocurrency companies are suddenly buying Super Bowl ads and sponsoring MLB umpires. Are these just well-funded ponzi schemes?

As a Bitcoin (or other cryptocurrency) miner, you run the Bitcoin software (or software for the coin you’re going to mine). The “puzzle” is built into the operation of that software.

That’s not a controversial subject at all Ignoring that, you’ll find that many of the companies provide services to people in the crypto community. I’m sure you’ve heard the adage that in a gold rush, the ones that make money aren’t the gold miners, but those selling supplies to the gold miners. There’s an element of that in crypto. Crypto exchanges (where people buy and sell cryptocurrency) take their percentage regardless of whether the people using the exchange make or lose money.

Ignoring that, you’ll find that many of the companies provide services to people in the crypto community. I’m sure you’ve heard the adage that in a gold rush, the ones that make money aren’t the gold miners, but those selling supplies to the gold miners. There’s an element of that in crypto. Crypto exchanges (where people buy and sell cryptocurrency) take their percentage regardless of whether the people using the exchange make or lose money.

I live in an old gold mining town in California so I’m well aware of that concept. I have an old friend who’s convinced that he can make a million dollars selling NFT art even though he has no idea how it works. I keep trying to explain that adage to him.

I have an old friend who’s convinced that he can make a million dollars selling NFT art even though he has no idea how it works. I keep trying to explain that adage to him.

This is the so-called proof-of-work system.

In order to add a block to Bitcoin’s blockchain (and thus permanently record the transaction(s) contained within), some amount of cryptographic processing is required. The nature of the processing is that it is computationally expensive to add a new block, but very inexpensive to verify that a block (once added) is valid.

The algorithms are dynamically adjusted by the network in order to ensure that it is always computationally expensive - so the amount of work required goes up over time as hardware gets more powerful. It is also adjusted based on network load, in order to ensure that transactions are processed in a timely manner - when there are a lot of transactions to process, the amount of work goes down, and where there are fewer transactions, the amount of work goes up.

The idea is that you can’t add a block without doing all the work. This prevents attackers from spamming the blockchain - they would require as much processing power as the rest of the network combined in order to have a significant impact.

As a reward for donating the CPU horsepower to the network, when a block is added to the network, the owner of the computer (or pool of computers) that completed the computation first is awarded a small amount of Bitcoin. This is why “miners” are willing to buy so much hardware and consume so much electricity to perform these computations.

The interesting thing is that the purpose of all this computation is not to secure the blockchain, but to prevent small players without the necessary investment in hardware from being able to directly alter (and therefore potentially corrupt) the distributed database.

There are other techniques used by other cryptocurrency networks that don’t involve massive server pools (and the energy consumed by them). One (which Etherium plans to switch over to at some point in the future) is proof-of-stake, where priority is given to those nodes that manage the most assets on the network.

There are many other proof-of-whatever systems that try to avoid network abuse by restricting transaction processing to nodes that contribute large amounts of memory/storage (proof-of-space), nodes that are pre-approved and trusted (proof-of-authority) and other algorithms.

Different algorithms are more suitable for some blockchain applications than others.

For instance, a blockchain run by a consortium of electronic parts manufacturers for tracking global supply chains, or one run by municipal governments to track land ownership would probably be best served by a proof-of-authority system, since you would only want authorized users to be able to modify the data. But a cryptocurrency designed to be independent of any central authority (e.g. Bitcoin) would definitely not want that algorithm.

Interesting point that we didn’t insert—maybe should have noted right above this, @ace @jcenters, that cryptocurrencies are founded on a white paper. Bitcoin was the model for this. First, you write a description of how your cryptocurrency works. Then you (and possibly others) implement it in code. That description in code is fixed unless 95% of mining capacity “agrees” to adopt updates that change how nodes process transactions or blocks work. (Smaller improvements or bug fixes that don’t introduce changes in block creation can be rolled out by nodes agreeing to update.)

So the Bitcoin algorithm as described in its white paper and written in code specifies the puzzle. The puzzle is basically:

The puzzle is: does the resulting hash in binary have a certain number of zeroes at the start before you hit a one? Because the hash’s output can’t be guessed from the input—that is the nature of a hash—the only way to “solve” the puzzle is to use brute force. So if the first test fails, increment the counter and try again. This might have quadrillions of times before any miner solves the puzzle.

Difficulty increases by requiring more leading zeroes and decrease the opposite way.

One thing I didn’t get into is that there are really four divisions in cryptocurrency: the miners, the node operators, the participants (people posting transactions), and the programmers. The programmers may work for mining firms or be entirely independent. They could work for foundations and nonprofits.

In order to get major changes in the underlying code approved, programmers have to implement it and then 95% of blocks mined in a certain period of time have to signal adoption of the updated protocol. If they don’t, the change isn’t made. Sometimes developers will “go on strike” and not roll out other improvements needed if miners don’t adopt protocol changes. It’s an interesting tension as you would think the miners had all the leverage!

They’re well-cashed-out Ponzi schemes. People who got in early can cash out holdings to later entries via exchanges which exists to swap cash and cryptocurrency. Some people are true believers and own riches only in code. Others, wiser, diversify and get real government currency they can spend directly. The more they advertise, the more people buy in, raising the exchange price, allow promoters to cash out more of their virtual currency into real cash.

This isn’t just limited to ads during the Super Bowl and other big sporting events, crypto companies have been furiously bidding to license their names on stadiums, a few have already been successful. Major League Baseball, other leagues and teams are actively courted by Cryptos as well, and not just for stadiums, but for stuff like patches on uniforms, logos on beverage and food containers, etc.

Here’s just a few examples:

Sports attracts huge audiences, whether broadcast, online, in stadium, etc. Establishing brand recognition, expanding bases of clients, building revenue. They are also focusing on luring away traditional banking, stock trading and other financial customers, as well as spreading the word among emerging markets of potential customers. And legalized sports betting has been spreading around the US; it recently became available in New York and we are being inundated with broadcast ads for online betting as well as crypto betting.

Even though it’s months away, negotiations about next year’s Super Bowl are underway. I suspect there will be even more crypto ads on next year’s Super Bowl and most other major sports.

Another important takeaway from this article is that there is a difference between cryptocurrency and the blockchain technologies that underlie it. Although all current cryptocurrencies are built over blockchain technologies, blockchain has many other uses, which I think will prove to be far more important over time.

(TL;DR: Blockchain: Yes. Cryptocurrency: No.)

IBM is one company that is conducting massive amounts of blockchain R&D. Their Hyperledger Fabric family of products is using blockhain technologies to manage enterprise data resources over a decentralized network of (presumably IBM cloud-based) servers, and is supposed to be lower cost than doing it the traditional way (e.g. with SQL databases replicated to many locations).

Most blockchains of this form will never see life outside of the company that’s running them. Definitely not cryptocurrency. But if the products live up to the marketing hype, they may prove to be a big cost saving to companies big enough to be able to take advantage.

Another example I’ve read about (but not yet seen in practice) is for things like real estate transactions. By keeping deeds in a blockchain (run by a local, county or state government), it should be possible to perform transactions much faster and cheaper than the way it’s done today. A seller and buyer could provide their data to this blockchain and transfer the property (after a valid sale, of course) without the time consuming and expensive process of manually recording the deed at a town clerk’s office. And if multiple municipalities decide to share a single blockchain (or link them in some other way), this could allow much easier cross-jurisdictional sales.

Again, this is not cryptocurrency. A real estate blockchain like this would almost certainly be run by the existing government authorities that record deeds today, and those authorities would be the only ones with permission to execute a transaction. But even this way, it could dramatically simplify and reduce costs for these transactions.

I just thought of another excellent motivation for crypto companies to invest in the Super Bowl:

Thank you for highlighting that! I’m not sure I did enough. I think of it as “value” versus “immutable public record” or at least “immutable record.”

Yes! Any kind of serial transaction in which records should never be deleted, but only updated or amended. If you look at county property records in the United States, they’re basically an unsecured “immutable” ledger. This would also be incredibly valuable for art provenance.

I miss the gold standard.

After a bit more reading, I realized that Hyperledger is not an IBM project, but is an open source project managed by the Linux Foundation: https://www.hyperledger.org/. IBM does sell products based on it. Many other big companies are members of this group, including

Some of the Hyperledger Foundation’s more interesting case studies (at least to me) include:

Yep. My personal opinion is that cryptocurrency and NFTs are just one big scam and they will eventually collapse into themselves because there is no intrinsic value in their concept. The tech has uses.

.but money it ain’t.

I always recommend reading Matt Levine at Bloomberg. You can subscribe to his free newsletter there, Money Talks. In today’s installment, he makes a funny and accurate summary of a big aspect of cryptocurrency:

and

I’ll second this recommendation. While you probably need to know a little bit about finance and investing, Matt does a great job of explaining some fairly esoteric things. He’s also a really funny writer. I mean, anyone that can come up with “the Elon Musk Division of the SEC”…

Great article. I’m still skeptical of the claims that it will be useful in the future.

Isn’t that already what Credit Card companies are?

It’s easy to imagine, but that’s the amount that the market has been willing to pay, so I see no reason why cryptocurrencies wouldn’t end up at the same market rate.

A PIN is a tightly controlled secret. In the US, credit card companies have not even required us to use a PIN to facilitate a transaction. The prospect of loss of spending in their system is apparently worse than the fraud that would be prevented by a tightly controlled secret.

The reason the fees are high is because that is a lot of work. Government could of course take on all of that work, but why would they? It’s expensive to do all of that. It would require a lot of tax money. It’s far cheaper for the government to simply require private companies that want to facilitate trans-border commerce to do those things. Why should the tax-payers subsidize trans-border commerce?

Companies tend to do this because that’s what they want. Nothing prevents anybody from setting up an organizational structure with proportional voting rights. If it isn’t happening now, it won’t happen just because of some new cryptocurrency. The fact that DAOs exist in a simplistic form just means they haven’t gotten complex enough to do what people actually want—separate classes of voting shares, etc.

Ok. That I understand. There was an Advent of Code puzzle in 2016 that was basically this. I had no idea I was learning how to be a bitcoin miner!

Fidelity is jumping head first into the crypto waters:

…and the pool has no water in it.

It’s possible their announcement is premature:

@glennf - Nice article. Helped me to clarify some of my addled thoughts about cryptocurrencies.

One small correction: it wasn’t the wallet developer who removed Moxie Marlinspike’s poo-emoji-swapping NFT, it was OpenSea the NFT marketplace! And, to top it off, they made it disappear from all crypto wallets.

So much for write-once, immutable register-of-record.

More blockchain related than cryptocurrency, but anyway. You’re more into blockchain and Web3 than I am. Is this domain service for real and legit? I have no way to judge.

Warren’s Buffett’s take on Bitcoin:

Thanks for this informative article. I’ve got a question…

PoW mining advocates say that blockchain security is so much better with PoW than with other methods of consensus like Proof of Stake.

I’m not saying I buy it, but I’ll go with it…

But is there any benefit to the security of the blockchain (or any other benefit) from having more and more rigs, more and more hash power, more and more mining farms getting into the game - or is it all just a money grab?

The argument is that PoW produces a sort of active contention for control that’s mediated by the desire of all parties to not destroy the value of the blockchain or associated cryptocurrency. So because you cannot reverse blocks out of the blockchain or fork it without having 51% control (and theories suggests 40%+ is enough), you must demonstrate your work through investment in continuous calculation. You can’t just manipulate the records. The encryption is underpinned by the enormous amount of work that can’t be reproduced except through comparable work.

Proof of Stake requires an anti-fraud/anti-collusion system in which people are risking value they put into the system by being unreliable. With a majority of reliable actors, it’s impossible (they say) for an unreliable party with skin in the game to overcome the reliable actors and manipulate the contents of the blockchain or fork it. However, this has never been tried, and a new protocol that’s that complicated and doesn’t rely on brute force could have flaws that would lead to exploitation without risking stake.

Yup. I get that. But if the hashrate in the world never increased from what it is now, and the mining pools stayed as diverse (or even increased their diversity) so 51% attack was not possible - would there be any harm vs the option of more and more hashing, more and more energy consumption…

The mining pools aren’t diverse. There’s a widespread understanding that the current ownership consolidates control into a handful of parties.

Still not good:

However, there’s no likelihood of a point of stasis: either Bitcoin grows in value and drives an ever high hashrate or it shrinks into obscurity and the hashrate could drop to something that isn’t nearly as horrible.

Ok. That’s what I’ve been trying to get at. There is no point, no “productive purpose” to the increasing hash rate, and massive energy waste from more and more mining. The blockchain isn’t any more secure, or any better off because another 10,000,000 ASICs have joined the game.

Thanks.

Thanks Glenn, useful as always and a handy article to point to when it comes up in conversation.

I can’t help but observe that it is far removed from regular folks understanding of economic transactions and wealth. Further, it is a set of technologies that will not gain public confidence from being foregrounded or explained. If anything going into detail on them makes them appear worse.

It’s a big ugly bad mess, we can do better.

Hi Glenn,

I shared your article with a coworker who’s into crypto currency. Here are some comments he wrote, and which he “authorized” to publicly share with you:

In case you’d like to respond to any of his points, I’ll very gladly pass those responses back to him. :) Thanks!

This is awesome—particularly because he’s clearly a realist!

100% agreement. Bitcoin has all the attention and Ethereum has had governance issues and PoS is always six months away. It’s hard to believe in a better proof-of when nobody feels particularly motivated who has money in the game. (The stakes in Ethereum 2.0 are real, but we are years into a promised transition that’s always just that far away.)

I am actually very interested in this and have interviewed some of the people who created things like ZCash on previous projects (pre-crypto). I think it’s very difficult to explain and the mojo doesn’t seem to be going that way. But it is absolutely an interesting counter-argument to a lack of true anonymity. However, if Monero et al succeeded, I think governments would go absolutely insane and create mass enforcement actions to prevent exchanges from trading in and out due to the threat of how it might be used for illegal transactions.

Absolutely. Is that where more than a fraction of activity is occurring? Absolutely not. So it’s one of those “the solution exists; nobody is using it” (where nobody = it’s a side issue compared to the main solutions). I think Layer 2 solutions have the problem of building on a landfill of rotting timber: if your problems exist in Layer 1, a second layer isn’t the solution. But it has an appeal in terms of transaction speed and cost.

Stablecoins are all extremely suspect because of the cash reserve issue. Some stablecoins hedge and use cryptocurrency as a method to reduce the cash they keep in reserve. As a result they are using imaginary money to peg their imaginary money to real money. Tether is the poster child for this with USDT, not one of the ones listed, but it’s the biggest by far and is one of the key liquidity players in Bitcoin. If it were to collapse, and I predict it will based on its shaking footing, it will cause a massive drop in $-to-Bitcoin valuation.

Gruber linked to this interview with a computer scientist who studies cryptocurrencies today. The money quote:

Yes, he’s pretty smart on this. Strident! I disagree with how he says “buybacks and dividends” make the stock market a positive-sum game. The ever-increasing value of the market does that mostly. It seems like a small point, but if you’re comparing crypto, which has no intrinsic value and it’s valuation is always marked through illiquid exchanges based on stress—no central bank can shore up Bitcoin, etc.—then the stock market is based on the continuous value of underlying assets combined with the optimism of future earnings growth.

If you say “crypto has winners and losers and the stock market doesn’t [for long-term investors]” that’s not totally it. Crypto has no reason why some people are winners and losers, and the rapid climb in value means that it’s a Ponzi scheme, as people cash out only by hyping more people to come in so they can take those people’s money via those limited exchanges that allow cashing into fiat.

The stock market also picks winners and losers, but because on average over any reasonable period of time (like any 15-year period), it has a significant average positive return, the losers are only the ones who stay in for short periods. If you climb on the ride at any point and stay on it, you exit at a higher level. (Based on the last century, including the Great Depression.)

Excellent response and explanation. My investment advisor says the same thing. People only lose money in the stock market if they sell their stock.

Until you sell, you haven’t lost a penny despite what your brokerage statement says today’s value is. If the reason you bought a stock is still valid, there is no reason to sell. Let it sit and grow long enough and you can take out money monthly and never lose your principal.

This was a hard lesson to learn when I look at my 401(k) and see 4 figure losses every day from panic selling. But I have learned from a great investment adviser the truth of what you wrote.

Within 18 to 24 months of every market crash over the last 100 years, if you have good stocks, the market comes back and the stock goes higher than it ever was before the crash.

Buy, hold, and grow richer. Apple, Amazon, and Google are not going out of business anytime soon.

Another important lesson that’s hard to internalize is that your portfolio value moves in percentages, not absolute dollar amounts.

If your portfolio is worth $10,000, then a 1% swing equates to $100. But if your portfolio is worth $250,000, that same 1% swing now equates to $2500. And if your portfolio is with $1.5M, that 1% swing now equates to $15,000.

The overall impact on your net worth is the same in all three cases, but when your portfolio gets large (which is not unusual if you’ve been steadily contributing to a retirement plan for over 20 years), those swings can seem really scary. You just need to remember that the market swings both ways, and that large portfolio will translate to similarly large (in absolute dollar amounts) gains when the market recovers later on.

Which is why most advisors today recommend against picking individual stocks. It’s very hard (nearly impossible over long periods of time) to figure out which stocks will win and which will lose. But the aggregate behavior of the entire market is quite predictable (over long periods of time). Hence the advice to invest in passive mutual funds and ETFs - so you have a little bit of everything and can therefore benefit from the general upward trajectory of the market as a whole.

But also rebalance. Otherwise, your portfolio ends up getting skewed away from the asset allocation you want (or that your advisor is recommending).

For example, let’s take a trivial example where you want to have 50% stocks and 50% bonds. Now let’s say that the stocks outperformed the bonds one year - they grew in value faster than the bonds did. So after a year, your portfolio is now (for example) 60% stocks and 40% bonds. And if this happens again for another year, you may end up with 70% stocks and 30% bonds - which is a far more aggressive portfolio than you wanted.

The solution is to rebalance. Sell some of the stocks (the “winners”) and buy bonds (the “losers”) with the proceeds, so you end up once again with 50% of each. And when the market swings in the opposite direction in the future, only 50% of your assets (the stocks) will be affected, instead of 70%.

Any brokerage firm should be able to set up your account this way. Tell them what investments you want, and at what percentage of your portfolio. And then tell them to periodically rebalance (perhaps quarterly or monthly) in order to keep the overall allocation similar to your chosen percentages.

Some financial companies can even monitor your asset allocation and trigger rebalancing when the pattern drifts more than some percentage from your chosen allocation, instead of based on time elapsed, which is even better, if you have the option.

It’s not just about being broad. It’s about going passive because of much lower cost. If you’re targeting net 4% revenue, but your commission comes in at ~1% (instead of say 0.03%), that’s devastating over the course of 20 years. You want something like an ETF on the S&P500 (on the stocks side) to get both broad coverage as well as lowest possible cost. And then if you want to go really broad you can start worrying about mixing in some non-US/Japan/EU based stocks. There’s of course ETFs that target exactly that too.

Passive is definitely important. Although some fund managers claim to be able to beat the market, and advertise such an objective, no manager has ever been able to do this consistently over time. They may get lucky for a few years, but then they will also have plenty of years where they are not so lucky.

But you don’t want only an S&P 500 fund. That will get you the 500 biggest US large-cap stocks, but you also want small-cap and mid-cap. You want some growth stocks and some value stocks. You want US, developed foreign markets and emerging markets. You also want some bonds - government, corporate and maybe others. Real estate and precious metals are also important. And you want coverage in all market sectors - consumer staples, energy, finance, healthcare and many others.

Fortunately, there are ETFs for all of these. You can probably cover everything with a dozen or so carefully-selected funds. As for which ones to hold and in what proportions - that’s what you need a good financial advisor for. The mix should be custom tailored for your specific goals, objectives and risk tolerance.

Yes to all the above. After years of using the late, long-term Yale endowment investment manager David Swenson’s advice for individual investors—a carefully adjusted, ruthless balancing of stocks, bonds, domestic, and international—I finally shifted nearly everything in the retirement account into a Vanguard target date retirement fund. They basically do all the work for me and the fee right now is, IIRC, .08%, down from .1% a few months ago.

I realized they were using very much the same strategy. I’d already moved all my accounts to Vanguard after reading Swensen’s book, as he explained some of what everyone did just above: management fees are the killer without producing better returns on average over the long haul than passive investment in low-fee funds.

Vanguard does indeed make a lot of this fairly simple, without requiring you to pay $$$ for somebody else to do it for you.

A not insignificant part of my retirement is in the UC system (which is managed by Fidelity) and they make a big deal about how they change the bond/stock/cash ratio as you get closer to retirement age. It’s of course a perfectly sound idea to have more stocks (with their higher expected returns over longer investment periods) when you’re farther from retirement, and then increase the bond ratio as you get closer and need more security because you’re about to start drawing down.

But, honestly, most of that anybody can do themselves without a paid manager or a fancy brokerage. You’re rebalancing anually anyway (assuming you’re not being borderline reckless), so you can include in that another step where your balancing also takes into account the stock/bond split. Naturally, financial people like to also drag in real-estate and metals and yada yada, but truthfully, that’s icing. For most people, if they just gave up on individual stocks, actively managed funds, and reduced instead to roughly 2-3 bond ETFs plus 2-3 stock ETFs, they’d be 90% of the way. You can always do better, but I’d never advocate for letting perfect be the enemy of good (where good is already much better than what likely most regular Joes are doing today).

All good advice, folks, but let’s keep it focused on cryptocurrency going forward.

Cryptocurrency is dead, Adam!

Just stumbled across this enjoyable story from @paul1 about a Bitcoin scam that he played out and profited from to the tune of $5. My takeaway is that the entire cryptocurrency world is sufficiently confusing and opaque that it makes scams like this far more possible. If the scammers did this with regular money, no one would fall for it (he says, optimistically, but probably not realistically).

Every time I read about the FTX implosion I think about this article and the ensuing discussion. Matt Levine from Bloomberg has been covering it in his Money Stuff newsletter. It’s horrifying but he makes it hilarious. This is in the initial report from the guy who was installed as CEO to handle the bankruptcy liquidation:

It was just a bunch of bros who had no interest in accounting or keeping records. Their balance sheet was just some manual entries in an Excel spreadsheet. Expenses were approved by thumbs-up emoji in a group chat. There was “an unsecured group email account as the root user to access confidential private keys and critically sensitive data.” They didn’t even keep track of who their employees were!

FTX was worse than simply a Ponzi scheme. It’s hard to fathom how it was valued at $32 billion. Reading Levine’s newsletter really boggles the mind. I highly recommend it. It’s a free subscription and is good for laughs and head-shaking.

https://www.bloomberg.com/account/newsletters/money-stuff

What, you mean that there’s a reason why adults exist? :-)

No, it’s not. People see “crypto” and think “get rich quick”, which always leads some people to lose whatever critical thinking skills they may possess. If you can technobabble your way through things, you can convince investors without having the slightest shred of competence.

As an artist, I had briefly considered trying to sell NFTs. A little research convinced me that it was something I didn’t want to touch at all. Yes, it’s possible to make good money from it. But it’s more probable that you’ll get burned, no matter how diligent you are, because most of the companies you would have to work with don’t appear to be doing their own due diligence sufficiently. FTX may have been the worst, but they absolutely are not special in this regard.

Crypto may someday be useful, but right now, it’s primarily a way to part fools and their money.

The Verge featured excerpts from the FTX bankruptcy filing:

The full filing is available here.

New York State just passed a two-year moratorium on cryptocurrency mining operations that use fossil fuels for proof-of-work validation methods. Nice to see this issue getting local attention!

I wasn’t sure if moratorium meant “halt” or “holding up new stuff.” There’s a good CNBC story about it that digs in further. Sounds like because permits won’t be issued or renewed, there could be shutdowns of projects underway—but some of those projects can continue for a period of time within the next two years.

I do love how the crypto proponents are saying it creates high-paying jobs, when often it creates like, two or three jobs. So, yeah, it’s money injected into a community…and that comes with a cost of noise, pollution, and often increased utility costs and other failures.