How To Avoid AI Voice Impersonation and Similar Scams

AI voice impersonation puts a new twist on an old scam, and you and your family need to be prepared. Forewarned is forearmed when criminals can take snippets of online audio and use increasingly widely available tools to make a sufficiently convincing AI voice, bolstered by claims to be on a poor phone connection.

I encourage you to have conversations among your family, at least—but maybe also within your company or social groups—so everyone is aware that these kinds of scams are taking place. The best defense relies on a shared secret password or other information only you and the purported caller would know.

How the Scam Works

The kind of fraud related to AI voice impersonation is typically called the “grandparent scam.” It works like this: The phone rings in a grandparent’s home, usually early in the morning or late at night. They answer, and it’s one of their grandchildren saying they have been in an accident, arrested, or robbed. They need money—fast. The connection is often poor, and the grandchild is in distress.

“Is this really Paolo? It doesn’t sound quite like you.”

“Grandma, it’s me. I’m on that trip to Mexico I told you about, and thieves stole my wallet and phone! Can you wire me some money so I can get a new phone?”

The grandparent leaps to help by running to a Walmart or Western Union—or even withdrawing cash from a bank and handing it off to a “courier” who arrives at their home. And their money is off to a scammer.

The FBI says this particular scam first reared its head in 2008, likely because of the confluence of inexpensive calls from anywhere, the ease of transferring money worldwide instantly, and social media making it easier for fraudsters to discover facts about people that let them make plausible assertions.

Of course, this scam doesn’t always involve grandparents, and I don’t mean to imply that older people are more easily fooled. Scammers also target children, parents, distant relatives, friends, neighbors, and co-workers. Sometimes the caller alleges to be a police officer, a doctor, or, ironically, an FBI agent.

The key element of the scam is that a close family member, friend, or colleague is in dire need. The purported urgency and potential threat against the caller’s freedom or ability to return home override the normal critical thinking most people would bring to bear. The scammers also often call in the middle of the night when we’re less likely to be alert, or attempt to take advantage of cognitive declines or hearing problems in older family members.

The AI voice impersonation aspect adds a “future shock” element: none of us are prepared for a call from a thoroughly convincing version of someone we know well. It’s already happening. The FTC highlighted it in a post on March 2023. And you can find news accounts around the country, meaning it’s just a slice of the whole scam ham: the Washington Post on a Canadian fraud, March 2023; Good Morning America, June 2023; New Mexico, September 2023; and San Diego, November 2023; just for instance. Posts on forums abound, too, like Reddit.

Services arose last year that can produce a credible voice impression from fairly small amounts of audio, notably ElevenLabs. The AI voice is eerily accurate when seeded with a few minutes of audio. It doesn’t cost much to generate a voice clone, and many services have few or no safeguards to prevent misuse, a variety of which happened almost immediately. The FTC is soliciting proposals on how to identify and deter voice cloning fraud.

It’s unclear how the scammers acquired a recording of the person’s voice in some cases. Obviously, if someone is a podcaster or appears in YouTube or TikTok videos, those are likely sources. But it’s also plausible that a generic voice of the right age and accent could fool people. There’s an outlier that’s occurred, too: a caller, who had to be an AI, tried to scam a grandmother in Montreal in part by dropping in Italian nicknames, like calling her Nonna. That’s uncanny and would have required a high degree of research for a relatively small financial gain.

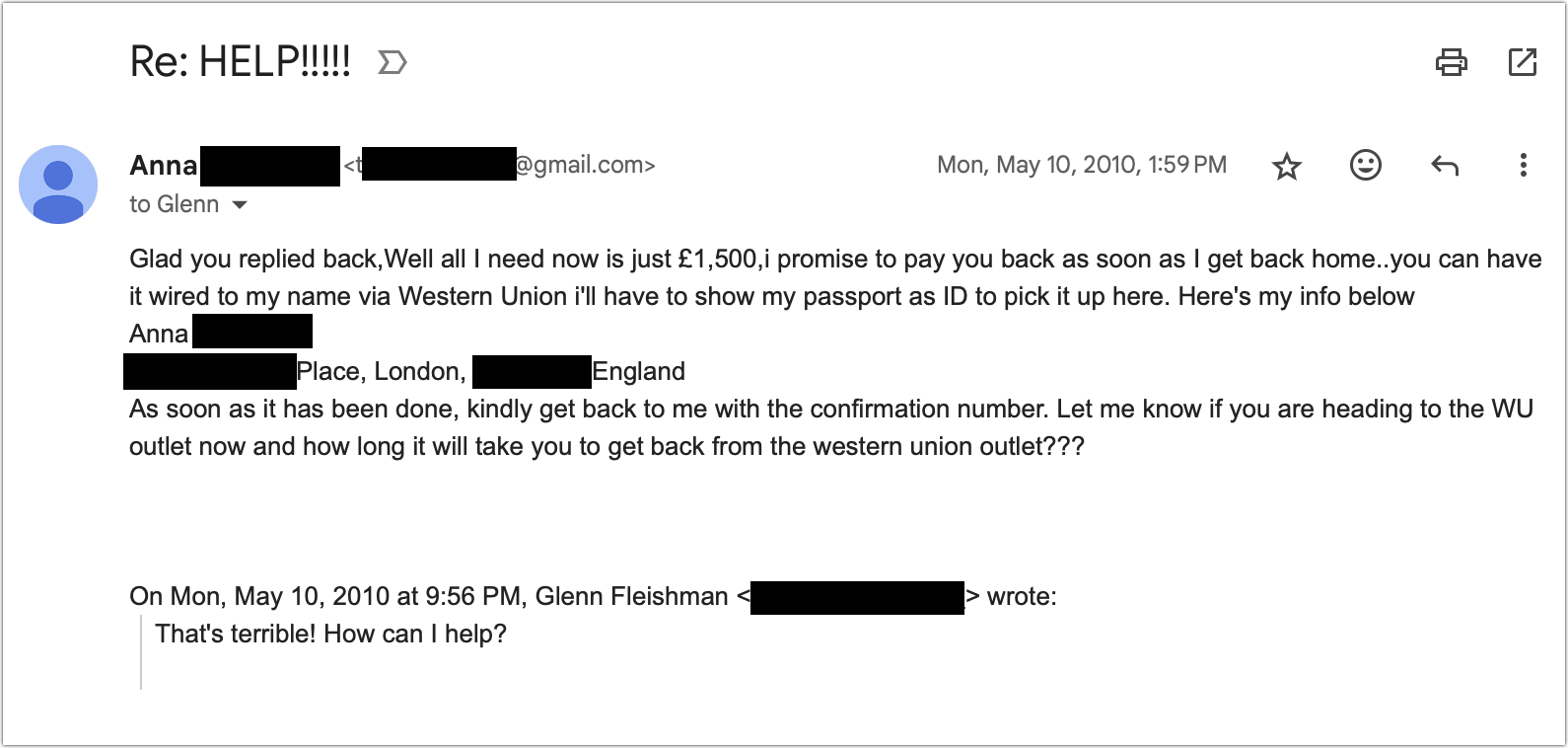

These scams can also come in by email, though they are often far less convincing due to less of a feeling of urgency, as well as issues with diction, spelling, and other written factors. I received this email in 2010 from my “friend” Anna. The real Anna was someone I knew and liked but wasn’t close enough to for her to ask me to borrow a pile of money, and she was well-spoken and careful with words in my interactions with her. The first email was brief; I replied and got what you see below. It’s not convincing—but that was before we had generative AI penning such letters.

The Robots Are Coming for Your Money

You can beat most of these scams with a shared password among family, friends, or co-workers. As with most aspects of verification, the process requires an out-of-band channel for information. Essentially, you want to provide a secret or details over a communication method that isn’t the same one you’re securing with that information. (We write about the out-of-band issue so much at TidBITS, we should form a musical group called “Out of Band”)

Your group should set up a password for situations where you need to confirm identities over the phone. Let’s say it’s “raspberry beret.” If you get a call from a loved one in trouble, you can say, “Look, there are scams, and we talked about this—what’s the password?” The password should be something familiar that’s easily remembered but not associated with you online. A family joke can be good. You don’t have to be strict about them getting it perfect—you’re not verifying their nuclear launch code authority.

If the caller can’t remember the password, dig deeper and ask for personal facts—they should be readily available to a person you know well. “Do you remember what Uncle Don told you?” “No, I don’t remember what he said.” “You don’t have an Uncle Don.” (As a result of researching this article, my family now has a password.)

You can also identify and defeat these scams through simple means:

- While stalling the caller (pretend to be sleepy or confused), surreptitiously text the person at their known phone number to confirm their situation.

- Say you’ll call them back, then call the person’s known phone number. A criminal will likely claim that their phone was stolen or not working. In many of the stories linked above, when the scam failed, it was because the victim placed a call or sent a text.

- Try to get them to switch to a video call “like you always do.” So far, AI isn’t good enough to provide live video impersonation of an arbitrary person.

- Call or text a relative or other person in common who might be more informed about the alleged caller’s location if they can’t be reached immediately.

- Call a police station where the person claims to be calling from.

I also hope all TidBITS readers know this, but police departments and lawyers never ask for funds to be wired through Western Union, Walmart or Amazon gift cards, Bitcoin, or the like; they don’t demand the money be sent immediately; they don’t make threats; and they don’t tell you not to call anyone to confirm the facts. While behavior like that should cause even the most trusting person to take notice, we’ll rarely be in these situations in our lives, so we can be taken unaware. It’s essential to consider the possibilities ahead of time to establish the pathways you’ll need to defeat scams under pressure.

I mentioned earlier that email can be much less convincing, using the example of my friend-of-a-friend’s hijacked email account and message. So I asked ChatGPT to compose an email to my grandmother telling her I was robbed in Mexico and my cameras were stolen. The first try was stilted, so I told it to use simpler, less formal language. On the second try, it came up with what could be a convincing message with no red flags:

Subject: Need Help Grandma! Got Robbed in Mexico 😟

Hey Grandma,

Hope you’re doing okay! So, guess what? I’m in Mexico right now, but something crazy happened. I got robbed! Yep, they took my cameras and some other stuff. But don’t worry, I’m totally fine, just a bit shaken up.

I really need your help with this. Can we talk about it soon?

Miss you and can’t wait to see you!

[Your Name]

No, ChatGPT, no! Generative AI assistance can easily eliminate the usual unconvincing use of language, idiom, and tone that characterize most “grandparent scam” attempts. Imagine an email interchange or live chat with someone who sounds like someone you know and love, trust, or work with, and who can answer a lot of basic questions. That’s why you must be ready with a shared password, backchannel confirmation, or video chat.

I’ve been sending a URL for those seniors I know or supported in the past to the AARP. Which has some good info for “seniors/retirees” about the current scams and to report.

There was a recent SFC article about a couple whose son was the reported called in an accident, and the mother was so upset and just fell for it all. Adrenaline and worry are powerful, as the mother clearly was so upset not to “just call her son”.

Thanks Glenn!

If you get a cal from a “relative” under suspicious conditions like this, ask a few questions that a third-party will always get wrong.

For example:

Or maybe:

or maybe:

I’m sure everybody can think of questions along these lines, where anyone impersonating your family will try to answer the question instead of responding with complete confusion.

That was the story that sparked me writing this!

We have to be evangelists on this and tell other people—if you’re reading TidBITS, you know! But I think there’s a bit of naivety both in the young and old who are not sophisticated online people but are online all the time. My kids were a bit gullible at times; fortunately, never got catfished, phished, or otherwise scammed.

My dad, in his 80s, is a sophisticated online user (he designed websites for a while, even), and he’s trained himself to double check stuff with me. He’s usually very dubious, which is good. Apple sent him a ridiculous email that was entirely legitimate and he thought it was phishing!

10 years ago, my (elderly) parents got a call from the “police” telling them that their grandson (my son) was in jail in the big city close to where my parents lived. The scammer talked fast and was convincing enough to get my parents to ask about bringing a check to the police station to bail out the kid. When the “cop” said a check wouldn’t work, Dad finally hung up the phone and called me.

I was able to reassure them that the kid was asleep in his room (I looked in at him) 1,500 miles away.

Talk to your family and friends! Tell them about this type of scam. Stress that if it was a real emergency, they would be able to get a case number and call back AFTER checking to see it was legitimate.

Some people (especially older folks) have trouble with being “rude.” I practiced with my mom to get her to say a quick “Goodbye” and hang up the phone when scammers called.

Excellent article! My wife and I just discussed one of the ideas Glenn mentioned and we’ve decided that if our ‘kids’ call us and it sounds suspicious we’ll just tap the ‘FaceTime’ button in the phone call. Our kids have iPhones and shouldn’t have a problem using FaceTime, but as Glenn says, scammers would likely reject the FaceTime call. If that happened we’d have some probing questions for them.

Yep…FaceTime and questions.

The problem with this is that the call may not show up as coming from their phone. In a real situation, one of the issues may be that they lost their phone and am calling from another. So, I don’t think this is a good test unless the call claims to be from their phone.

I do like the password and the various questions that may or may not have a real answer.

A frightening element to this is that banks and other agencies are, supposedly, using voice recognition to identify customers. Back to square one!

Some UK banks, we get:

bank auto-switchboard: "please say ‘My voice is my password’ "

customer: “my voice is my password”

…I guess not anymore it isn’t!