Slack AI Privacy Principles Generate Confusion and Consternation

Mea Culpa: I inadvertently based this article on a later version of the document than the one that triggered the online controversy. Most of my criticisms below are thus misplaced, and I apologize to those I impugned. Read my full explanation here.

Answering questions, making telephone calls, and (perhaps) telling jokes may be some of the things you think of when you think of Siri, but Apple’s digital assistant has many more tricks up its sleeve.

As I traveled home from Salt Lake City last Friday, controversy began to swirl around the popular group messaging system Slack, which we use and cover regularly. A Slack online document titled “Privacy principles: search, learning and artificial intelligence” went viral after it was discovered that Slack failed to use the Oxford comma in its title. Wait, no, that’s wrong—the controversy came about after a link to the privacy principles was posted to Hacker News with the title “Slack AI Training with Customer Data” and boosted on X/Twitter, focusing on how the document includes an awkward opt-out-via-email provision if “you want to exclude your Customer Data from Slack global models.”

Well, heck, yes, who wouldn’t want to exclude their data from Slack global models? One of Slack’s selling points is its promises surrounding privacy and security, so confidential business and personal information can be discussed with impunity. If Slack were training large language models (LLMs) on customer data, anything you say in Slack could be ingested into the model, digested by the neural network, and spit back out in who knows what situations and contexts. Maybe your competitors could even ask Slack AI to reveal your business secrets! Quick, panic on social media!

If people actually read Slack’s privacy principles document instead of just reacting to an incorrectly titled link or an out-of-context screenshot on X/Twitter, they would see that Slack isn’t doing any of those things. Refer to unambiguous sentences like:

We do not develop LLMs or other generative models using customer data.

No Customer Data is used to train third-party LLM models. Slack does not train LLMs or other generative models on Customer Data, or share Customer Data with any LLM providers.

That’s not to say Slack’s privacy principles are a paragon of clarity. The document uses a variety of terms without defining them (what’s a “global model,” and is it generative AI?), waits until the end to mention that Slack does use generative AI for the separate Slack AI product offering (but not LLMs trained on customer data), and tends to mix what Slack doesn’t do (develop LLMs using customer data) with what it does do (develop non-generative AI/ML models by analyzing customer data) in the same paragraph.

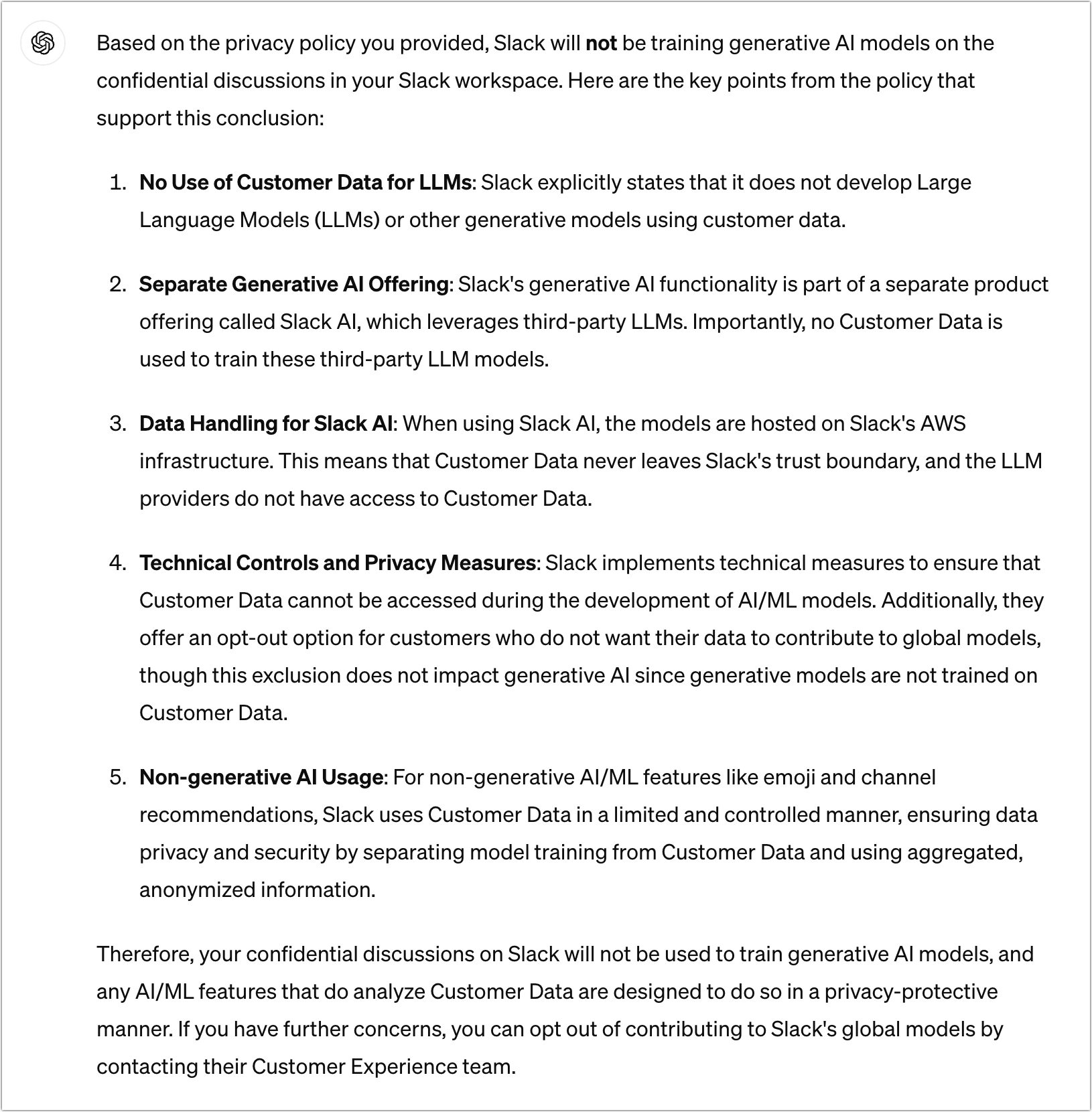

The entire kerfuffle occurred because people didn’t read carefully and posted out-of-context hot takes to social media. If only we had a tool that could help our social media-addled human brains extract meaning from complex documents… Hey, I know—I’ll ask ChatGPT if Slack will be training generative AI models based on the confidential discussions in my Slack workspace.

There you have it. ChatGPT: 1, random people on social media: 0. Unless, of course, ChatGPT is in cahoots with Slack AI, and that’s just what they want us to believe.

I also asked ChatGPT to tell me what people might find confusing about Slack’s privacy principles and to rewrite it so there would be less chance for confusion. You know what? It did a pretty good job calling out Slack’s definitional and organizational problems and creating a new version that relied heavily on headings and bullet lists to get the point across more directly. Paste in Slack’s privacy principles and try it yourself sometime—chatbots can do a decent job of telling you what’s wrong with a document.

More seriously, there’s an important point to make here. Even as we rely ever more on gadgets and services, society has lost a great deal of trust in the tech industry. This controversy arose because the suggestion that Slack was doing something underhanded fit a lot of preconceived notions. Slack didn’t even get enough of the benefit of the doubt to cause people to read its privacy principles carefully.

This lack of trust in how the generative AI sausage is made is understandable. OpenAI and other firms trained their LLMs on vast quantities of information from the Internet, and although that data may have been publicly available, using it to build and maintain billion-dollar businesses doesn’t feel right without compensation or at least credit.

Worse, will anything you say—or documents you submit—to an AI chatbot be added to future training data? Although the privacy policies for all the leading AI chatbots say they wouldn’t think of doing any such thing, prudence would suggest caution when sharing sensitive health, financial, or business information with a chatbot.

I fear there’s no returning to the techno-optimistic days of yesteryear. Experts say a company can regain trust with clear and transparent communications, consistent competence, ethical practices, a positive social impact, and a serious attitude toward stakeholder concerns. That would be difficult for even a motivated company and seems impossible for the tech industry overall.

But I’m not worried about Slack for the moment.

It continually annoys me how quick people are to assume all businesses are up to absolutely no good and want to rob us blind of our money, our data, and our freedom of choice. Every single time one of these “leaks” comes out, people jump on the out-of-context quotes and extrapolate to infinity on things that were never said and, when the original context is examined, weren’t even implied.

I want to blame the shortening of attention spans for the inability to understand that everything exists within a greater context, but I can’t help but wonder: are people really getting so much dumber, or is it just the reduced cost of broadcasting unvetted and unedited opinions making it seem that way?

While it may be true that people jumped to conclusions, another lesson might be to have tech companies write things clearly, and not in legalese that sounds like its trying to hide things by default.

BUT… using ChatGPT to ‘prove’ that Slack isn’t doing naughty things… the same ChatGPT that hallucinates left and right, is of questionable value.

The opacity and mind-numbing length of corporate policy statements, user “agreements” and the like have certainly contributed to the loss of trust in tech companies. I first noticed this several years ago when I tried to read a user agreement before buying some software. The web page including the agreement timed out before I could finish. Since then it’s gotten worse, and I’m afraid the tech companies themselves have become a huge problem. That’s a damned shame because technology has made tremendous contributions to our society, but today’s technology companies are becoming all about profits.

They’ve always been this dumb. Just to pull one example, Proctor & Gamble in the 1980s had to deal with many years worth of accusations that they were in league with Satan:

A major mea culpa here. When I first became aware of this situation on May 17, I was traveling home from a conference and didn’t have time (or much connectivity) to read the original document. I also had no time to devote to the topic on Saturday or Sunday due to helping my in-laws move and timing a trail race, so I didn’t return to the topic until Monday. By that time, Slack had updated the document (on May 18) to include the unambiguous sentences I called out. I actually had the thought that it might have changed and consulted the Wayback Machine, but the changes started in the second paragraph and were quite minor until the addition of the Generative AI section at the end. It was close enough and I was moving quickly enough in an attempt to meet my Monday publication deadline that I erroneously assumed the document was the same.

With all that in mind, many of my criticisms are misplaced, and I apologize to those whom I’ve impugned. The May 17 version of the document that triggered this situation does not explicitly call out generative AI or large language models, although none of the examples it gives (channel recommendations, search ranking, autocomplete, and emoji suggestions) involve generative AI.

The main problem with the May 17 version is that it’s old. Its first instance in the Wayback Machine was from October 2020, when it was titled “Privacy principles: search, learning and intelligence” and gives roughly the same examples. Although the document has changed since then, it’s an obvious evolution. It’s notable that the first version doesn’t even use the term “artificial intelligence” or mention AI and ML—it predates ChatGPT and the generative AI boom.

The criticism that Slack requires workspace admins to send email to opt out of the global models is legitimate, although I’m not sure it’s necessarily any harder to send email than to find a setting in Slack’s proliferation of options. From Slack’s perspective, the likelihood of anyone wanting to opt out of pattern-matching that would recommend channels and suggest emoji was probably sufficiently unlikely that no one thought to build a setting. It was only after these features became associated with AI that it seemed unreasonable.

All that said, I still feel like Slack’s mistake in failing to update the document to be more clear wasn’t that bad. The subsequent changes Slack made show that even if the document wasn’t as clear as would be ideal, Slack wasn’t trying to put one over on us. Even in the problematic May 17 version, Slack said:

Of course, because of the lack of trust many people have in the tech industry, even relatively clear statements like that don’t necessarily have the desired effect. “Sure,” one may think, “that’s what you say, but how do we know that’s true?”

And we don’t. There are many lapses, security breaches, and broken promises. But simultaneously, we have to trust the technology we use to a large extent because the only other option is to stop using it.

Well done Adam for explaining more. You’ve spent quite some time comparing versions of documents, which is something that shouldn’t be necessary.

Tech companies will email ‘privacy policy update, making changes to this, that and the other’ area, but not summarising what the changes are, or even telling us where they are in a meaningful way. That comes across as trying to hide the changes, or as making it as hard as possible to find the changes while fulfilling their duty to notify us. That in itself builds distrust.

Transparency surrounding revisions to online documents is an interesting issue, and I’m not sure there’s a single right answer. For instance, I regularly make silent changes in TidBITS articles until the point when I publish them in an email issue. After that, I only make changes for very small typos and other infelicities that couldn’t cause confusion. If I need to make a more significant correct, I publish another article, much as I just did with iPhones Pause MagSafe Charging During Continuity Camera - TidBITS.

Of course, as you point out, significant changes should be noted. We don’t have a good standardized way to do that on the Web, but there should at least be a revision date. Ideally, the Wayback Machine would make comparing versions easy, but I haven’t found that to be the case. Maybe I need to do more research into how it works.

This is another instance where Ted Nelson’s Xanadu had it right, at least in theory. Everything was under version control at all times.