TidBITS#1244/08-Oct-2014

Apple debuted Activation Lock in iOS 7 to discourage phone theft, and the company has now launched an online tool that can determine if a given device is locked. Josh Centers explains how to use the new Activation Lock checker and why you should when buying a used iPhone. Apple and Google are taking steps to make their devices even more secure, and some law enforcement officials are crying foul. Security Editor Rich Mogull examines both sides of the debate. Also this week, Josh dives into the world of iOS 8’s new third-party keyboards, and in FunBITS, he takes the Manual camera app for a spin. Notable software releases this week include Backblaze 3.0, GraphicConverter 9.4, OmniFocus 2.0.3, ChronoSync 4.5.3 and ChronoAgent 1.4.7, Carbon Copy Cloner 4.0, 1Password 4.4.3, and DEVONthink/DEVONnote 2.8.

What You Need to Know about Activation Lock

With new iPhones on the market, it’s prime shopping season for used iPhones as upgraders look to sell their older models. But as much as used iPhones can be a good deal (an iPhone 5 is still magic!), buying used can be stressful, due to working with a stranger, dealing with payment logistics, and worrying if the iPhone has any unseen problems. However, thanks to a new tool from Apple, you can at least make sure the iPhone isn’t stolen.

Back in iOS 7, Apple introduced Activation Lock, which is enabled when you turn on Find My iPhone in Settings > iCloud. (It works similarly on the iPad and iPod touch, but I’ll focus on the iPhone here.) When Activation Lock is enabled, it prevents:

- Disabling Find My iPhone

- Erasing the iPhone

- Activating the iPhone on a cellular network

The point of these features is to discourage theft, since once Activation Lock has been enabled, a stolen iPhone is worthless to a thief. Or at least it is as long as potential buyers know to check if Activation Lock has been turned on.

There are two ways to disable Activation Lock, which you would need to do before sending it in for service or selling it to someone who will need to reactivate it on another account. You can turn off Find My iPhone in Settings > iCloud, or you can erase the device entirely with Settings > General > Reset > Erase All Content and Settings. In either case, you will be prompted to enter your iCloud password first — that’s the key fact that a thief is unlikely to know.

Of course, if you know your iPhone was stolen, you can use Find My iPhone to put it into Lost Mode or even wipe it remotely to ensure that your data stays private. Activation Lock remains in place on a wiped iPhone to ensure that it can’t be reactivated by the thief — it’s just an attractive paperweight at that point. (Should a stolen iPhone be returned, you can restore it from backup, entering your iCloud password when prompted to get past Activation Lock.)

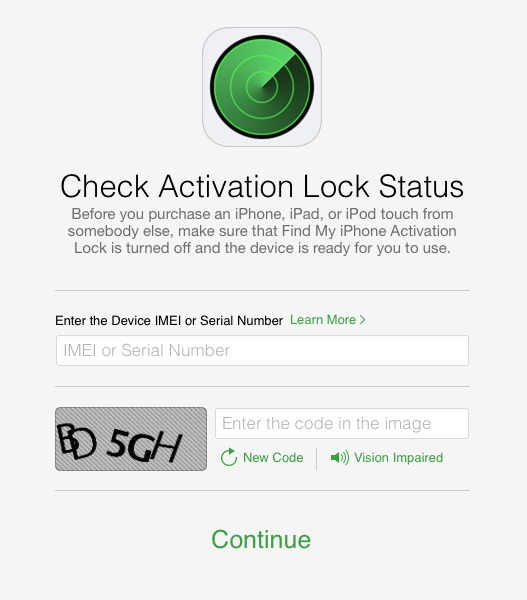

So, where does all this leave you, the prospective used iPhone buyer? As I mentioned above, Apple has introduced a Check Activation Lock Status tool (note that it doesn’t work on mobile browsers). To use it, you need the IMEI or serial number from the device, which can be found in Settings > General > About. The IMEI or serial number can also be found on the rear panel of the device, if you have really good eyes or a magnifying glass.

To check the status of Activation Lock on a device, enter the IMEI or serial number, then enter the CAPTCHA. I had problems trying to read the CAPTCHA, so it might take a few tries. Alternatively, click Vision Impaired to hear an audio CAPTCHA.

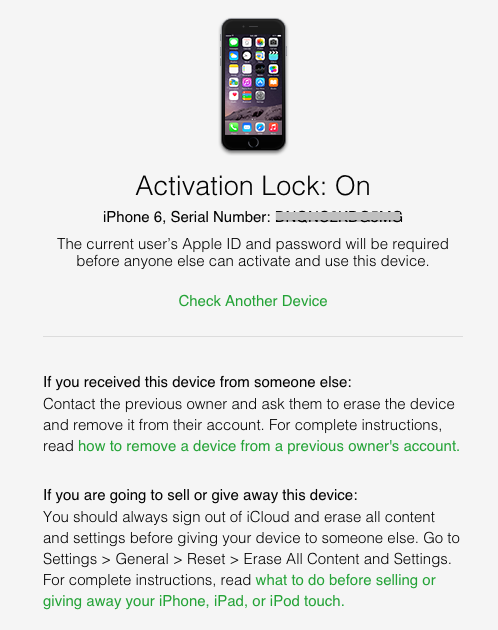

The Web page then informs you whether Activation Lock is on or off. If it’s on, Apple provides links to additional resources.

To make the most out of Apple’s Check Activation Lock Status tool, I recommend asking the seller to provide the serial number or IMEI before agreeing to the purchase. That way, you can make sure that you’re not wasting your time, or potentially getting into an undesirable situation.

Apple and Google Spark Civil Rights Debate

One small feature in iOS 8, barely mentioned during the keynote at Apple’s Worldwide Developer Conference, has engendered a major civil rights controversy. Apple said that, starting with iOS 8, all Apple-provided apps would be encrypted with Data Protection, which entangles your passcode with a special ID embedded in your device, that not even Apple can recover.

The implications were clear for months, but sprang into the public consciousness only after Tim Cook released an open letter on Apple’s privacy stance, highlighting that the technology would nearly eliminate the possibility of Apple accessing data on your device, even if compelled to try by law enforcement or the government (see “Apple Goes Public on Privacy,” 24 September 2014). This was quickly followed by FBI Director James Comey stating, “What concerns me about this is companies marketing something expressly to allow people to

place themselves beyond the law.”

Other law enforcement officials followed with their own condemnations. The chief of detectives for the city of Chicago even said, “Apple will become the phone of choice for the pedophile.” Ouch.

Before I go on, there are three things you need to know about me:

- My day job is advising companies and governments, big and small, about how to improve their security. One of my specialties is mobile devices and another is cloud computing.

- As an emergency responder (formerly a full-time paramedic, also with firefighting and mountain rescue experience), I have more than once had to tell parents that their child had died, often for easily avoidable reasons.

- I have three small children of my own.

Perspective is important. As writers, we are always biased by our experiences, especially with emotional issues that pit our civil rights against fundamental fears for ourselves and others. We shouldn’t vilify law enforcement officials who see access to our phones as important to their mission to protect us, yet we also can’t allow low-frequency statistical events, however great the emotional impact, to create even greater, more generalized risks.

iPhones Have Long Frustrated Law Enforcement — When the iPhone first came out, I was one of a group of analysts who advised enterprises to avoid it, largely due to security concerns. The original iPhone didn’t really have any security, but it also lacked apps. Since then, Apple has dramatically improved the resiliency of the platform from attacks, even if someone has physical possession of the device.

This level of security comes thanks to how Apple implemented Data Protection in iOS. Your iPhone is always encrypted, but in a way that is easy to circumvent. Data Protection enhanced the basic encryption by entangling your passcode (if you set one) with a unique identification number burned into the hardware of the device. There is no way to pull that code off the device, which dramatically increases the length of the “total” passcode that protects your encryption key.

One of the more effective techniques to crack phone encryption is to pull the data off the source device, and then brute-force attack it from larger, more powerful computers. By adding that device code into the mix, Apple makes it effectively impossible to crack iOS encrypted data on even the biggest computers, even if you can get the image off the device. Thus most forensics tools used by law enforcement (and criminals) have to crack the encryption on the iPhone (or iPad) itself, using the embedded processor that mixes the device code back in. However, this hardware is rate-limited, so once a passcode hits about six characters, it could take many years (even centuries) to break via brute force.

Data Protection has been around for at least three revisions of iOS devices, but for most of that time it protected very little: email (which the police can get from servers) and any apps that turned on the Data Protection API. Apple has never been able to access this data… for anyone. However, plenty of other data was exposed, including text messages, photos, app data that didn’t turn on Data Protection, contacts, and much more.

I detailed all of these limits in my iOS data security papers, because they were major security headaches for my enterprise clients. If you really wanted to secure data on an iOS device, you needed to be extremely careful and use all sorts of additional security controls. That’s why I traveled to China using only “clean” devices that didn’t have access to my normal accounts or data.

iOS 7 expanded Data Protection to all third-party apps (even those that don’t use the Data Protection API), and iOS 8 expanded it to all Apple-provided apps, including Messages, Camera, etc.

Apple didn’t deliberately lock out law enforcement to protect pedophiles, it added a much-needed security control to protect all of us from common criminals.

The Bane of Backdoors — It shouldn’t be a surprise that some law enforcement officials consider it their right to access our phones. Since the dawn of civilian law enforcement, we have granted police investigative powers: the ability to access anything outside our heads, with a proper court order.

With probable cause, the police can read our mail, enter our homes, listen to our phone calls, and more. That’s how many of them view the world — not with totalitarian malice, but as a legal privilege entrusted to them to protect society. Get the warrant, get the order, get the information. It’s all part of the legal process.

But technology advances have created a modern society that is no longer so clean. There is a term in the defense world called “dual use.” It describes technologies that can be used for good or evil. As a ski patroller, I used explosives to trigger avalanches. The same explosives are used in construction and in some military munitions.

Law enforcement, especially federal law enforcement, has a history of desiring and imposing backdoors into technology. The Communications Assistance for Law Enforcement Act (CALEA) of 1994 requires all telecommunications equipment manufacturers to enable remote wiretapping for law enforcement in the hardware. But CALEA backdoors have also been abused by criminals and intelligence agencies.

Last year, the New York Times revealed that the Obama administration was on the verge of backing CALEA-II, which would require any Internet communications service to include a backdoor for direct law enforcement wiretapping. All chat programs, social networks, and even webcasting tools would have had to provide a secret entrance for law enforcement.

Even dismissing concerns over NSA monitoring, it is technologically impossible to build such backdoors without the possibility of abuse by attackers. All wiretapping interfaces are dual use, and subject to abuse. No one has ever created a monitoring technology immune from attack or misuse.

In a short-sighted attempt to maintain existing investigative capabilities, the FBI is pushing to reduce communications security for the entire Internet, which would also destroy the competitiveness of U.S. companies globally. Then again, Microsoft is currently being held in contempt of court for not providing U.S. law enforcement private email messages from a customer in Ireland, from a data center in Ireland, even though doing so would violate Irish law. It’s a court case that could decimate the global market for all U.S.-based cloud computing providers.

A Rusty Key — On 3 October 2014, the Washington Post Editorial Board proposed Apple and Google build in a “Golden Key” to provide law enforcement, and only law enforcement with a court order, access to phones. That isn’t something I’m opposed to in concept — except it is technologically impossible.

I don’t know a single security expert or cryptographer who believes a secure golden key is viable. Especially not one that would be accessible to a range of law enforcement officials, over time, for various cases. It simply can’t be done. The closest equivalent is the fourteen holders (and seven backups) of the Internet DNS signing keys. That’s a system that works only due to their geographic distribution, and infrequent meeting requirements. A law enforcement equivalent could never handle ongoing law enforcement needs.

And that ignores the international implications of creating a backdoor to all phones, one that could be abused by any government.

Apple clearly sees its security as a competitive advantage, as I wrote, months before Tim Cook’s message. Especially since Google, by nature of its business model, can never maintain privacy as well as Apple, despite recent failures, no matter how strong its security capabilities. (Remember that privacy and security are not the same thing!) But all that marketing doesn’t eliminate the fact that Apple closed a long-known security flaw first, and leveraged the marketing later.

Attorney General Eric Holder claimed Apple and Google are “thwarting” law enforcement’s ability to stop child abuse. I have witnessed such abuse. Perhaps not on the scale of an FBI agent, but I know what horrors lurk in the world, and I have directly seen the consequences. These are things I don’t talk about outside the circle of former coworkers who have been there themselves. No matter how statistically rare it is (and most abuse is by a family member), like all parents I fear for my own children. Being on what reminds me of 24/7 suicide watch for the first years of their lives — fretting about SIDS, the

consumption of inedible objects, power outlets, and other infant dangers — is hard to forget. If something happened to them, I wouldn’t care about what laws or social norms impeded my ability to protect them, and I know the feeling of helplessness when you lack the resources or ability to save someone else’s child. These are powerful, emotional forces.

I fully understand the drive and motivations the law enforcement community has to maintain access to our devices. That access speeds up or breaks open cases. It enables police, at times, to better protect us from the worst the world has to offer. I understand how they can perceive Apple and Google as interfering with their ability to collect data they are legally entitled to access in the course of their duties. Data that could, at times, save lives.

But law enforcement needs to understand that technology companies aren’t trying to protect the bad guys, but stop them. That until iOS 8, I had to walk my clients through the iOS security loopholes that made it difficult to protect corporate and personal data. That such backdoors are already used to suppress free speech throughout the world, sometimes with fatal consequences. That without this encryption, we are all less secure.

Society is in the midst of a major upheaval powered by technology. One where the lines of privacy, civil rights, and the role of government are shifting as we fundamentally alter our social and communications structures. We need to decide if, as we make this transition, we will provide our governments pervasive access to all of our information, which simultaneously reduces our collective ability to defend ourselves from criminals. And we need to realize that if we err on the side of stronger inherent security, some criminals, even the worst of them, will occasionally get away.

iOS 8 Third-Party Keyboards Explained and Reviewed

One of the most intriguing features of iOS 8 is how Apple opened it up to third-party keyboards. Google’s Android mobile operating system has allowed developers to create custom system keyboards for years, which has led to interesting experiments, like Swype, which lets you draw on the keyboard to spell out words.

At long last, keyboards like Swype are available for iOS, but how you enable and use them isn’t always obvious. Also of concern is how these third-party keyboards, some of which connect to the Internet, impact your privacy.

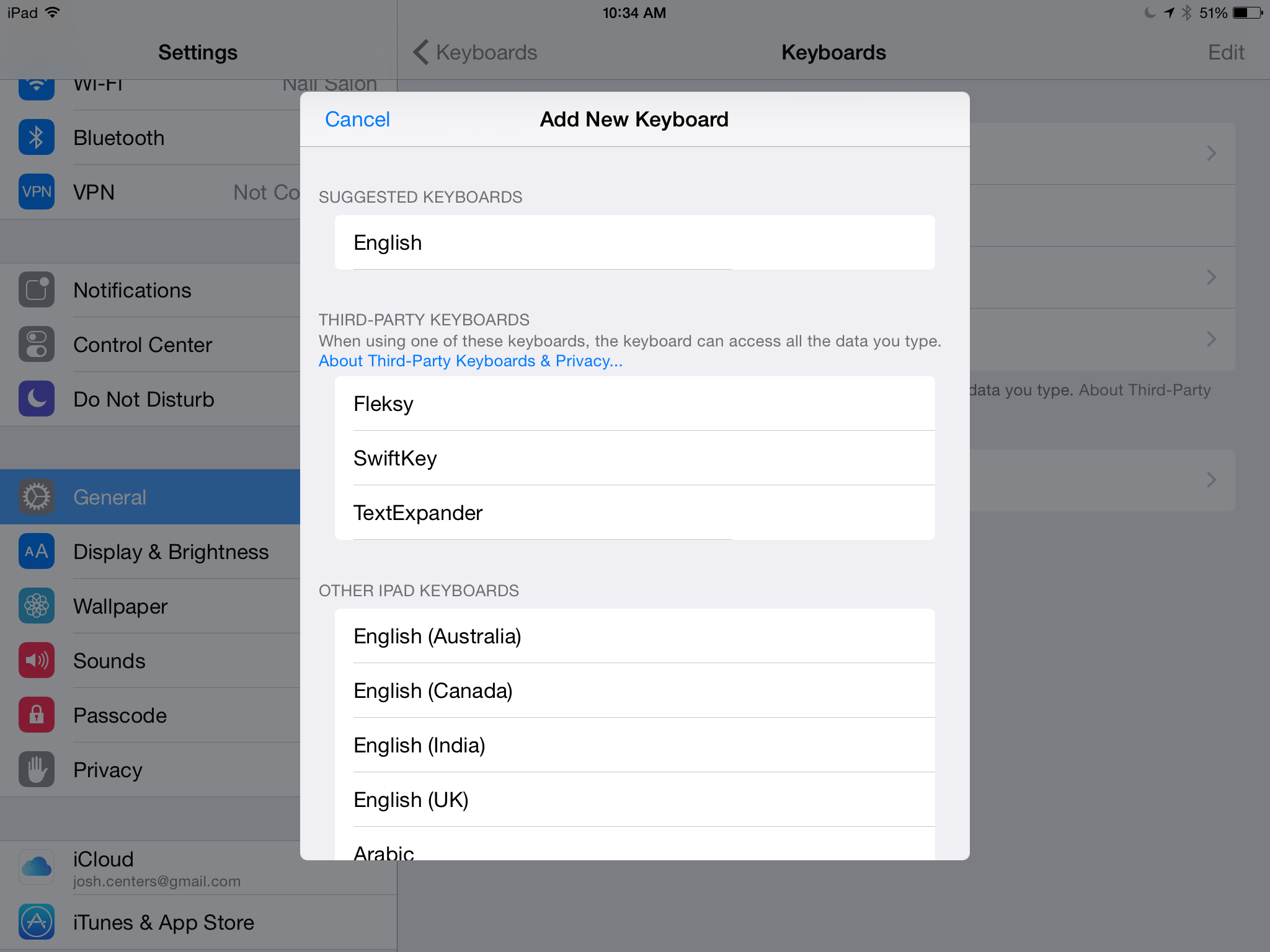

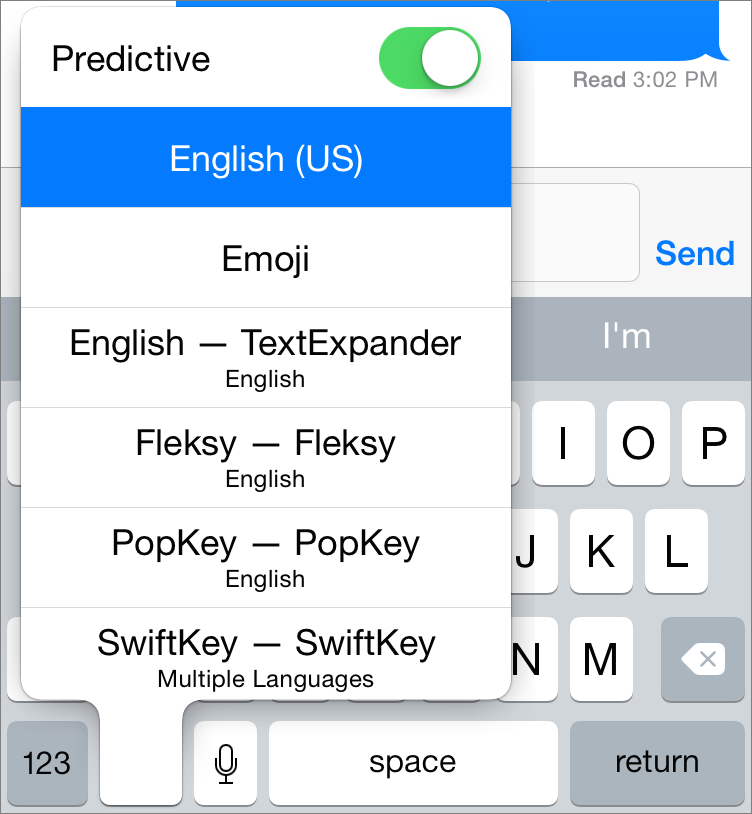

Setting Up Third-Party Keyboards — So you’ve heard about a keyboard, perhaps in this article, and you want to install it. The first thing to know is that keyboards are inherently associated with apps — if you want the Fleksy keyboard, you need to download and install the Fleksy app from the App Store. What next?

Somewhat confusingly, you don’t activate the keyboard from the app itself, though the app may give you instructions on how to do so.

Instead, here’s how to set up a keyboard: navigate to Settings > General > Keyboard > Keyboards > Add New Keyboard. You should see a heading titled Third-Party Keyboards. Under that, tap the keyboard you want to add. That will usually add the keyboard, though in some cases, you might have to choose a specific option. For instance, Smile’s TextExpander offers keyboards for five languages.

So what’s the app for, if you don’t add the keyboard from it? For most of the keyboards I tested, the container app offers additional settings, instructions, or even a space to practice with the keyboard. It may also provide some of the keyboard’s data or capabilities, as it does in the case of TextExpander. And of course, the app is how the keyboard gets into the App Store.

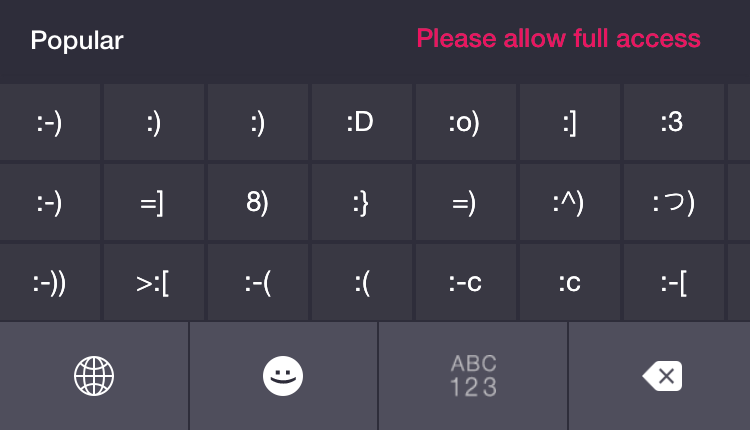

What Is Full Access? — Most of the keyboards I’ve tested require you to turn on Full Access by going to Settings > General > Keyboard > Keyboards, tapping the keyboard’s name, and then toggling the Allow Full Access switch.

After this, you’re given a stern warning before confirming that you indeed want to enable Full Access:

Full access allows the developer of this keyboard to transmit anything you type, including things you have previously typed with this keyboard. This could include sensitive information such as your credit card number or street address.

Yikes! But if you don’t enable Full Access, some keyboards are unusable. For instance, PopKey, which lets you type with animated GIFs, shows only emoticons until you enable Full Access. When Full Access is off, SwiftKey disables most of its features, like autocorrect, word suggestions, and SwiftKey Flow, and displays an obnoxious warning message.

However, even without Full Access, most keyboards work, just with fewer features. For example, Fleksy works fine, but you won’t be able to change settings, add new languages, add words to its dictionary, and other fairly minor things.

What does Full Access do, exactly? In the simplest terms, it enables the keyboard to communicate with its host app. There is nothing wrong with this, in and of itself. For example, for TextExpander to expand a text snippet, it needs to be able to look the snippet up in its database. On the flip side, that means that a keyboard can do anything an app can do, include transmit information, like keystrokes, over the Internet.

Unfortunately, this means that we likely won’t see more granular options for keyboard access in the future unless Apple re-engineers how third-party keyboards function.

However, as Smile founder Greg Scown pointed out in a blog post, apps have always been able to store and transmit your keystrokes. The difference is that there are now specific controls to prevent such behavior, and that capability is mostly system-wide.

Apple does limit third-party keyboards in certain ways to protect users. They cannot access the microphone or type into secure input fields (which should include all password fields, in theory), and app developers can bar the use of third-party keyboards in apps where the data is highly confidential, such as banking apps.

Apple also offers the following App Store review guidelines:

- Keyboard extensions must remain functional with no network access or they will be rejected.

- Apps offering Keyboard extensions must have a primary category of Utilities and a privacy policy or they will be rejected.

- Apps offering Keyboard extensions may only collect user activity to enhance the functionality of their keyboard extension on the iOS device or they may be rejected.

In theory, if a third-party keyboard were to do unscrupulous things with your keystrokes, Apple wouldn’t allow it in the App Store to begin with, and if it somehow slipped through, Apple would boot it from the App Store. But the information would have to leak out somehow for Apple to even know it should act.

In its developer documentation, Apple outlines certain things a keyboard should do, such as autocorrection and suggestion, which are the sort of things SwiftKey requires Full Access for. But Apple’s own guidelines say that a keyboard must remain functional with no network access. What is Apple’s exact definition of “functional?”

In reality, the only thing a keyboard absolutely has to do is provide a way to switch to the next keyboard.

Using Third-Party Keyboards — After setting up a keyboard, how do you use it? Tap a text field to bring up the keyboard, then tap the Next Keyboard key (it looks like a globe) in the lower left. You can also hold this button to see a popover list of available keyboards. Tap one to switch to it.

The more complex question is how to switch between third-party keyboards. Apple specifies that every keyboard must provide a way to switch between keyboards, but it unfortunately doesn’t specify a single way of doing that.

As a result, switching between keyboards looks and works a bit differently in each keyboard — it’s a mess:

- Fleksy: press and hold the globe key

- PopKey: tap the globe key

- SwiftKey: tap the globe key

- TextExpander: tap the Smile mascot

- Swype: press and hold the Swype icon, then slide your finger over the globe popover

If you have several keyboards enabled, switching between them is infuriating. Not only can there be a different method every time, but the keys are often in different places. Even Apple’s own emoji keyboard is guilty of this user interface offense, moving the Next Keyboard key one space to the left from the U.S. English system keyboard.

Even worse, developers can’t integrate the keyboard selection popover, so once you’ve switched to a third-party keyboard, you have to cycle through the rest one at a time.

Where Apple Can Improve — It’s early days for third-party keyboards, and there’s much Apple could do to improve the experience.

First, switching between keyboards has to become a smoother experience. Apple needs to give developers access to the keyboard selection popover so users can switch between keyboards quickly, and it should specify a location, name, and icon for the key that switches keyboards. Under the current rules, switching keyboards could technically be done via a gesture, leaving users to guess even more than they already have to.

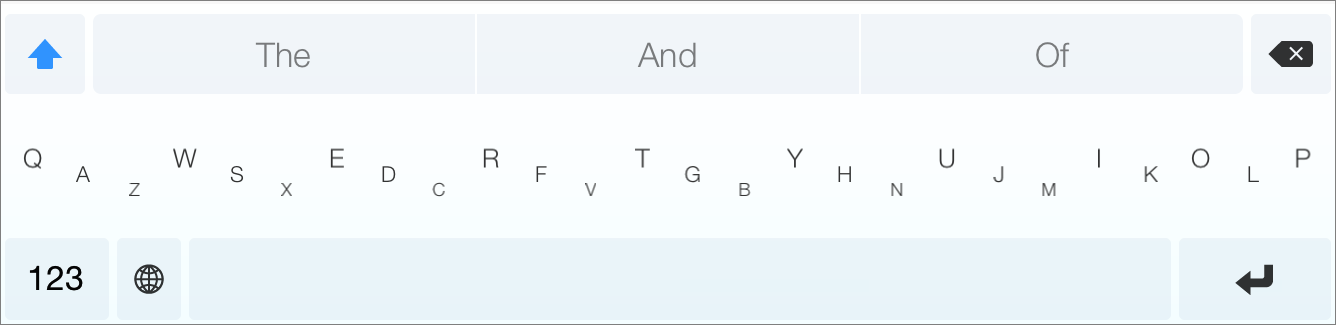

Second, there are many more keyboard resources Apple could open up to developers, like iOS 8’s auto-correction and text-prediction mechanisms. As it stands, developers must recreate every keyboard feature from scratch, which makes keyboards look and work significantly differently from the standard iOS 8 keyboard, which hurts the user experience unnecessarily. Ideally, an app could use the standard keyboard as a jumping-off point, and change only the desired functionality, rather than start from scratch.

Third, I’d like to see better privacy controls for keyboards. Perhaps I’m just paranoid because I’m not accustomed to the possibility of my keystrokes being recorded, but right now, you have the choice between letting developers do anything and having a partially functional keyboard. I’d like to see more granular privacy settings for keyboard container apps.

My Keyboard Recommendations — For the sake of simplicity, I’m going to divide keyboards into two categories: replacement keyboards and utility keyboards. In my terms, a replacement keyboard is a keyboard that’s trying to reinvent how you enter text across the board. In this category, I’d put apps like Fleksy, SwiftKey, and Swype.

Utility keyboards, in contrast, are those that offer capabilities unavailable on the standard keyboard. PopKey is a perfect example, since it types not with text, but with animated GIFs. I’d also include keyboards like TextExpander, since it’s handy to have access to your snippets throughout iOS, but you wouldn’t necessarily want to use it as your main keyboard in all apps.

The reason I’ve defined those categories is because my first recommendation is to pick one main keyboard (either the system keyboard or one of the replacement keyboards), and one or two utility keyboards, if needed, to augment it. You don’t want to enable too many keyboards at once or you’ll grow frustrated trying to switch between them. Two example setups might be:

- System keyboard, emoji, PopKey

- System keyboard, Swype, TextExpander (TextExpander snippets can insert emoji)

As far as main keyboards go, I have yet to find anything that compares to Apple’s system keyboard. It’s accurate, dependable, and best of all, is free and familiar. And with QuickType suggestions in iOS 8, typing is faster than ever before.

But if you’re looking for an alternative to Apple’s keyboard, Swype ($0.99) is currently one of the best, most polished options. Its innovative draw-to-type feature was invented by Cliff Kushler, who also developed T9 text input for traditional cell phones. I’m personally not a fan of drawing on my keyboard, but if you want to try it, Swype is the original and best.

Other interesting replacement keyboards are Fleksy ($0.99), which focuses on gestures, and Minuum ($1.99), which uses a hyper-compressed keyboard, depending on smart text prediction to get your wording right. I found both a bit too weird to use on a regular basis, but you may have better results.

The problem with replacement keyboards is that while many promise to save you time, they’re different enough from what we’re all used to that it takes time to adapt. Whether the time you save in the long run is worth the learning curve is questionable. Also, since you can’t use third-party keyboards in every situation, getting used to one and then having to go back to Apple’s, could be confusing.

I’d also like to take a second to discuss SwiftKey. One of the most popular Android third-party keyboards, SwiftKey is a jack of all trades, offering smart text prediction, Swype-like word drawing, and many other features.

But I don’t trust it. I didn’t trust it on Android, and I don’t trust it on iOS. There are a few reasons for this:

- It’s free. On Android, SwiftKey makes money by selling themes and other features through in-app purchases. But those have not arrived on iOS yet. There has also been talk of offering advertisements on the keyboard, though that is expressly forbidden by Apple’s App Store guidelines. In any case, I’m unconvinced by these business models, and I’m less trustful of companies that don’t seem to have a clear, dependable revenue stream.

-

It’s more insistent about requiring Full Access than any of the other replacement keyboards I’ve tried, to the point that it’s practically unusable without it.

-

It “helpfully” offers to scan my Facebook and Gmail accounts to learn my writing style. Creepy. No thank you.

The company addresses these concerns in a blog post, which explains that SwiftKey requires Full Access for advanced features, saying, “It is worth stating very clearly, however, that no language information leaves your device at all unless you opt in to our SwiftKey Cloud service to get these benefits.”

I remain unconvinced. But SwiftKey costs nothing to try, so let your judgment guide you.

I’m much more optimistic about utility keyboards. My current favorite is PopKey (free), which provides a database of animated GIFs, sorted by the feeling you wish to express. I like to think of them as advanced emoji. A winky face is one thing, but an animation of a famous actor slowly raising an eyebrow says so much more.

One thing I dislike about PopKey is that it required me to sign up with an email address and provide a phone number so I could receive an activation code. I never received the activation code, but the keyboard works anyway. Adrian Salamunovic, co-founder of PopKey developer WorkshopX Inc., told me that registration is needed to upload your own GIFs and transfer them between devices, and that the phone number activation is simply to make registration faster. Salamunovic also confirmed that it helps thwart the uploading of offensive or illegal content.

A less-invasive alternative to PopKey is Riffsy (free), though I’ve found Riffsy to be less reliable, and the images it provides tend to be all over the place size-wise, while PopKey provides consistently sized images. Both keyboards require Full Access to function. However, in this case, I don’t care, because what could anyone determine from animated GIFs I insert?

I’m also a fan of the new TextExpander ($4.99), which includes a third-party keyboard. Having access to my snippets everywhere in iOS is game-changing, especially since Apple’s iCloud sync of its own text shortcut implementation is unreliable. But I can’t yet recommend TextExpander as a main keyboard, since it still has some rough edges. It doesn’t offer any word suggestions, and a bug in the iPhone 6 and iPhone 6 Plus causes the keyboard to expand and contract somewhat randomly. (I’ve been informed that a fix has been submitted to Apple, and is awaiting approval.) TextExpander also requires Full Access, but developer

Smile (a longtime TidBITS sponsor) has a golden reputation, as well as an actual business model, so I’m totally happy to grant Full Access.

Third-party keyboards have a long way to go in iOS, but this is only the beginning. The entire situation will only improve with time, and even if you don’t care for any third-party keyboards now, they are entirely optional. My own misgivings aside, I’m thrilled that Apple has opened up this avenue for developers and users to address the significant problem of text entry in iOS.

To learn more about the power of iOS 8, pre-order my upcoming book, “iOS 8: A Take Control Crash Course,” which will cover third-party keyboards and other new features that will change the way you use your iOS devices.

FunBITS: Manual Gives You Total iPhone Camera Control

“This is an amazing camera, but sometimes it can be %$#&@^% stupid,” says developer William Wilkinson in the introductory video to Manual, a new camera app for iOS 8 that provides nearly complete control over your iPhone’s camera.

Wilkinson has a point. I’ve often found myself struggling to tell the iPhone’s camera exactly what to do, especially when it comes to what object in the scene I want to focus on. But for a mere $1.99, you now can take complete control of your iPhone’s camera.

A bit of a disclaimer: My skills are nowhere near those of photographers like occasional TidBITS writer Charles Maurer or our own Jeff Carlson. I struggled through my university’s photography class, eking out a hard-fought C. But, as I noted in “Canon EOS M Combines Quality and Simplicity at a Low Price,” (23 August 2013), I’ve managed to learn enough to take some decent baby photos.

For those who aren’t familiar with the fundamentals of photography (and these days, you don’t really need to be), they all revolve around controlling how much light is captured in an image, as determined by aperture, ISO, and shutter speed:

- Aperture: In simple terms, the aperture determines the size of the hole capturing light. Aperture is measured in f-stops, and the smaller the number, the larger the hole. So an aperture of f/1.4 is much larger than f/8. A lens’s stated aperture size is the largest size it can open up to. So if a camera lens is rated at f/2.5, that’s the widest it can open, and the most light it can let in.

- ISO: Referring to the ISO 5800:2001 standard, the ISO setting on cameras determines how sensitive to light the film or digital sensor is. In the days of film, ISO was determined by what film you had in the camera, but in the digital era, it’s a software setting. Higher ISO settings capture more light, but also introduce visible noise. Ideally, you want to use the lowest ISO setting you can get away with to minimize noise.

-

Shutter speed: How quickly a camera’s shutter opens and closes is measured by its shutter speed, in fractions of a second. The faster the shutter, the less light is allowed in, and the less risk of image blurring. A slow shutter speed lets more light in, but since the exposure is longer, any movement of the camera or the subject will result in blurring.

At one time, you had to be familiar with all of these fundamentals — and how to adjust them on your camera — to take a decent photo. But even with most cameras now attempting to be idiot-proof, understanding these basics enables you to pull off some neat tricks. For instance, if I’m trying to photograph an active baby in a dimly lit room, I know I need to max out shutter speed, open my aperture up as wide as possible, and increase ISO. If I wanted a motion blur effect, I would slow down the shutter speed, but since that causes more light to be captured, I would also tighten the aperture and reduce ISO.

Until iOS 8, Apple didn’t permit such control over the iPhone’s camera. The iPhone’s processor (and the dedicated image processor in recent iPhone models) automatically selects the settings to make the best image it can, and usually does a good job. But now, thanks to the increased freedom offered to developers in iOS 8 to control those aspects, an app like Manual has become possible.

But does Manual deliver on its tantalizing promise of offering complete, SLR-like control to the serious iPhonographer? Yes and no.

Manual lets you adjust a number of settings, most of which weren’t accessible before iOS 8:

- Exposure compensation

- ISO

- Manual focus

- Shutter speed

- White balance

You probably noticed the big omission: aperture! Unfortunately, the iPhone’s camera has a fixed aperture: f/2.2 on my iPhone 6. Since adjusting the aperture is a key way to control exposure, I can’t do many of the things on my iPhone that I can on my Canon EOS-M.

I have a simple camera trick I like to use for testing. To capture a motion-blur effect, I slow down the shutter speed, adjust aperture and ISO as needed, and then wave my hand in front of the camera while snapping a picture.

On the EOS-M, this is easily accomplished. However, with my iPhone 6 and Manual, it’s a lot more difficult. Since I can’t control aperture, it’s easy to blow out the image with too much light, resulting in a white rectangle instead of a picture. I was able to pull off a similar effect on both cameras, but it took some trial and error in Manual.

Of course, this hardware limitation is outside the Manual developers’ control. But I have a few other issues as well. Sometimes, touch targets are unresponsive, which, to be fair, seems to be a common bug with apps on the iPhone 6 and may thus be iOS 8’s fault. Also, when I dial down the shutter speed, the viewfinder responds in kind, displaying jerky video of what I’m looking at. While it sort of makes sense, no other camera I’ve used does that, so it’s disconcerting. Finally, Manual doesn’t have a… manual. Just

a terse FAQ. I think a lot of amateur photographers would appreciate at least an overview of what each function does.

If you’re interested in iPhone photography, you’ve probably already dropped the $1.99 to start playing with Manual. I don’t blame you. In fact, I fully expect much better photographers than I to do amazing things with it — I’ve been impressed by what people have been able to squeeze out of even earlier iPhone cameras. But set your expectations accordingly. While the iPhone has an amazing camera for a phone, it’s still a phone camera.

But if you’re not a photography buff, you don’t need Manual. The iPhone 6’s camera and image processor combine for better photos than I could take with my iPhone 5, and in iOS 8, you can adjust exposure and focus by tapping objects in the viewfinder screen. If you just want to pull out your iPhone and snap a decent-looking photo without manual intervention, the built-in Camera app is tough to beat.

TidBITS Watchlist: Notable Software Updates for 13 October 2014

Backblaze 3.0 — Backblaze has updated its eponymous backup software to version 3.0 with loads of under-the-hood improvements. Backblaze 3.0 (which is tied to the subscription-based Backblaze online data backup service) improves the efficiency and throughput of its data storage while also improving integrity checks for stored data, doubles the speed of the deduplication process for both initial and incremental backups, improves the speed and efficiency of breaking down and reassembling large files, and adds support for using 2 GB of memory on 64-bit systems. The auto-update process for current Backblaze subscribers will begin in

the next couple of weeks, but you can get this update now by downloading directly from the Backblaze Web site or performing a Check for Update within the Backblaze software. (Free with Backblaze subscription, 9.1 MB, release notes, 10.5.8+)

Read/post comments about Backblaze 3.0.

GraphicConverter 9.4 — Lemkesoft has released GraphicConverter 9.4 with several improvements and new features added to the venerable graphic conversion and editing utility. GraphicConverter is now solely a 64-bit app, and the update adds an auto-convert feature with batch conversion and folder watching capabilities, a function to add or remove a fisheye effect, support for saving embedded Photoshop paths in TIFF and JPEG formats, an optional full-screen preview to the browser, the capability to search by label in the browser’s find function, and the capability to set the default GPS location for

images without GPS data. The release also fixes a possible memory leak in the slideshow, a crash that occurred during the AppleScript Convert File command, and many other unspecified issues related to OS X 10.10 Yosemite. Note that the Mac App Store edition is still stuck on version 9.3 as of this writing. ($39.95 new, free update, 248 MB, release notes, 10.7+)

Read/post comments about GraphicConverter 9.4.

OmniFocus 2.0.3 — The Omni Group has released OmniFocus 2.0.3, a maintenance release that fixes some OS X 10.10 Yosemite compatibility issues as well as a few other bugs. The Getting Things Done-inspired task management app’s Clip-o-Tron tool now captures only the subject, a link, and any selected text from an email message in Yosemite (and OmniFocus requires the updated Clip-o-Tron 1.0.1). Newly captured links to Mail messages from Send to OmniFocus now work in both the Mac and on the iOS version of OmniFocus. The update also fixes a couple of

issues with viewing help pages on Yosemite, squashes a bug in Yosemite that split the original message link from a clipped email into two links, and fixes a problem with the compact layout mode that prevented the status circle and flag from being clicked. Note that the Mac App Store edition of OmniFocus remains at version 2.0.2 as of this writing. ($39.99 new for Standard edition and $79.99 for Pro edition from The Omni Group Web site, $39.99 for Standard edition from Mac App Store (with in-app purchase option to upgrade to Pro), free update for version 2.0 licenses, 44.2 MB, release notes, 10.9.2+)

Read/post comments about OmniFocus 2.0.3.

ChronoSync 4.5.3 and ChronoAgent 1.4.7 — Econ Technologies has released ChronoSync 4.5.3 and ChronoAgent 1.4.7 with improved compatibility with OS X 10.10 Yosemite. The ChronoSync automated synchronization and backup app also migrates away from using several deprecated APIs in Yosemite, provides a much shorter delay when performing a Trial Sync that finds a large number of nonexistent files, performs update checks via a secure connection, sets a volume’s Ignore Ownership state to Off when performing a bootable backup,

fixes a bug that interfered with the initial Document Organizer display and the auto-update check on launch, and fixes some animation glitches when running 10.9 Mavericks. The ChronoAgent utility receives some minor interface tweaks when running in Yosemite and improves its performance and error handling. (Free updates for both apps; $40 new for ChronoSync with a 25 percent discount for TidBITS members, 41.7 MB, release notes, 10.6+; $10 new for ChronoAgent, 12.5 MB, release notes, 10.5+)

Read/post comments about ChronoSync 4.5.3 and ChronoAgent 1.4.7.

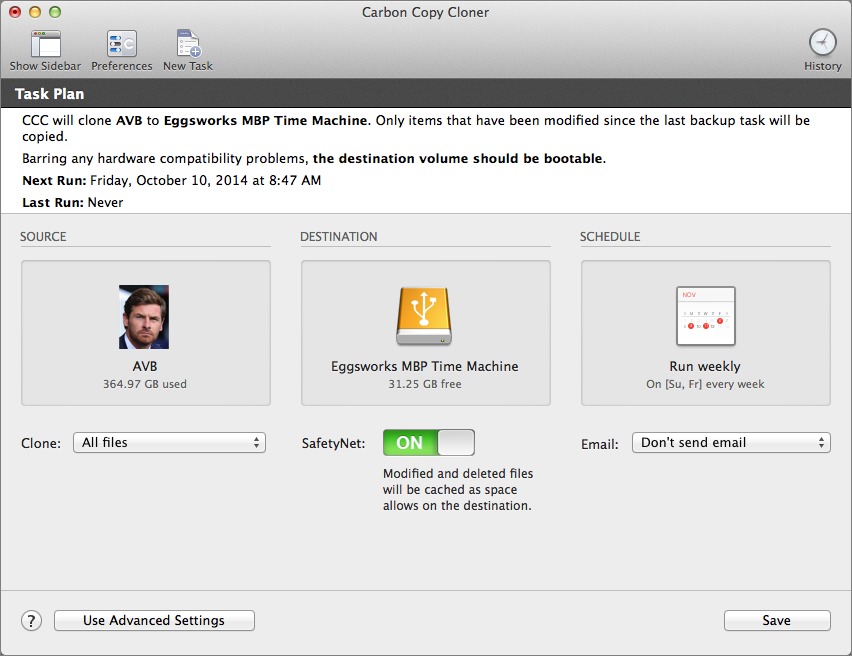

Carbon Copy Cloner 4.0 — Bombich Software has released Carbon Copy Cloner 4.0, a major update to the popular backup utility that comes just in time for the imminent release of OS X 10.10 Yosemite. Sporting a redesigned interface and architecture, Carbon Copy Cloner (CCC) adds many user-requested features, including a consolidated window that brings together task configuration and scheduled tasks, easier configuration of backup tasks, a menu bar application for quick access to task information, the capability to chain tasks together for more complex backup routines, and more control over when and how scheduled tasks run.

At this time, CCC 4 offers “provisional” support for Yosemite (as noted on this blog post), but a fully qualified update to CCC 4 will be released on or before Yosemite arrives in the App Store, with adjustments for a handful of cosmetic issues. Carbon Copy Cloner 4 now requires 10.8 Mountain Lion or later, but Bombich Software will continue to support 10.6 Snow Leopard and 10.7 Lion users with CCC 3.5.7 (for more on the move to CCC 4, see

this blog post). Carbon Copy Cloner 4 is priced at $39.99, and registered users of version 3.5 and later can upgrade at a 50 percent discount. If you purchased a CCC 3.5 license on or after 2 June 2014, you are eligible for a free upgrade. ($39.99 new, $19.99 upgrade from version 3.5.x, 11.0 MB, release notes, 10.8+)

Read/post comments about Carbon Copy Cloner 4.0.

1Password 4.4.3 — AgileBits has released 1Password 4.4.3 with several bugs squashed out of the popular password manager. The update fixes an issue that caused new logins from the browser extension to copy only the username and password fields, addresses a problem that prevented backups from being performed or restored on OS X 10.8 Mountain Lion, ensures that exiting edit mode without any changes does not prompt you to save or cancel, and fixes a couple of rare crashes. In addition to the Mac app, 1Password for iOS has

been updated to version 5.1 with a fix for an issue that caused the Master Password to be required at times instead of relying on Touch ID on supported devices. It also adds the capability to add tags and support for turning on third-party keyboards (for a review, see “1Password 5 Touches New Heights in iOS 8,” 1 October 2014). ($49.99 new with a 25 percent discount for TidBITS members when purchased from AgileBits, also available from the Mac App

Store, free update, 38.8 MB, release notes, 10.8+)

Read/post comments about 1Password 4.4.3.

DEVONthink/DEVONnote 2.8 — DEVONtechnologies has refreshed all three editions of DEVONthink (Personal, Pro, and Pro Office) and DEVONnote to version 2.8 to prepare for the coming rollout of OS X 10.10 Yosemite. In addition to updated Yosemite-friendly interface elements, the three editions of DEVONthink add a sharing extension that enables you to clip text and Web addresses with a single click (rather than using drag and drop). The DEVONthink updates also receive an improved Clip to DEVONthink extension that works from Safari’s reading

list (available from the Dock and Import menu), better conversion of Markdown to rich text, a fix for autocompleting in the Tags column when running Yosemite or 10.9 Mavericks, and the capability to set images in Web views as document thumbnails. DEVONthink Pro and Pro Office get a script for Safari that adds bookmarks for all the open tabs, while DEVONthink Pro Office updates support for ScanSnap Manager to version 6.x. DEVONthink and DEVONnote also add a Share submenu to the contextual menu of Web and PDF views (requires 10.8 Mountain Lion or later). (All updates are free. DEVONthink Pro Office, $149.95 new, release notes;

DEVONthink Professional, $79.95 new, release notes; DEVONthink Personal, $49.95 new, release notes; DEVONnote, $24.95 new, release notes; 25 percent discount for TidBITS members on all editions of DEVONthink and DEVONnote. 10.7.5+)

Read/post comments about DEVONthink/DEVONnote 2.8.

ExtraBITS for 13 October 2014

Josh Centers talks iOS 8 with The Tech Night Owl, Adam Engst discusses smartwatches with other tech luminaries, and we learn some lessons from the end of The Magazine.

Josh Centers Talks iOS 8 with the Tech Night Owl — Managing Editor Josh Centers joined The Tech Night Owl podcast to discuss iOS 8 in advance of his upcoming book, “iOS 8: A Take Control Crash Course.” Josh discusses what’s slowing iOS 8 adoption, how Apple can improve third-party keyboards, and what he expects to see from Apple’s next event.

Adam Engst Joins Pebbled Panel on MacNotables — The forthcoming Apple Watch may have sucked a lot of the air out of the wearable industry, but Adam Engst, Jason Snell, and Andy Ihnatko all have Pebble smartwatches (and Andy has quite a few other models as well). In this episode of MacNotables, they talk about what the Pebble does well, what other smartwatches need to do, and how it all relates to Apple’s announcement.

Nine Lessons from The Magazine — After two years, Glenn Fleishman is closing down his publication, The Magazine. In talking to Cult of Mac, Glenn outlined nine hard-learned lessons that prospective publishers would be wise to read. Some of The Magazine’s challenges were set in stone from the beginning: in particular, being reliant on Apple’s Newsstand feature, which changed for the worse in iOS 7, limited exposure.