TidBITS#1179/24-Jun-2013

Details surrounding recent allegations that the NSA can spy on users of online services continue to emerge, but in the meantime, TidBITS security editor Rich Mogull analyzes how much of your Apple data is actually vulnerable to government spying. Big Brother may be watching you, but will we be watching Big Brother? Jeff Porten looks at the social implications of wearable computers, ranging from smartwatches to Google Glass. Meanwhile, back in the present, Michael Cohen takes another look at the now-improved Marvin ebook reader, and Josh Centers runs down the recent channel additions to Apple TV — HBO and ESPN, notably — and clarifies the old-world catch that will prevent cord cutters from watching. Lastly, Josh wraps up the issue with the latest installment of FunBITS, featuring the Apple Design Award winner Badland for iPhone and iPad. Notable software releases this week include Mellel 3.2.1, Java for OS X 2013-004 and Java for Mac OS X 10.6 Update 16, TweetDeck 3.0.2, and Hazel 3.1.1.

Marvin Redux: A Smart Ebook Reader Gets Smarter

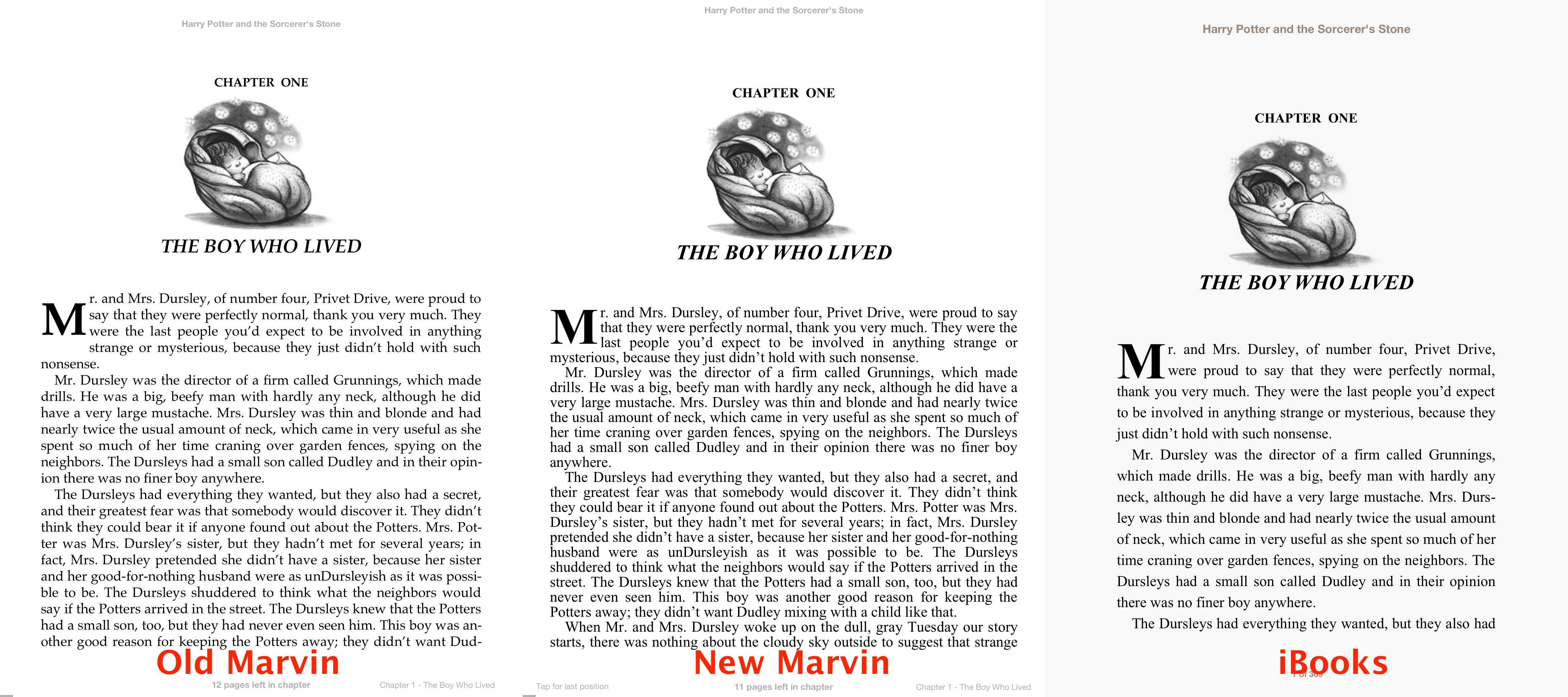

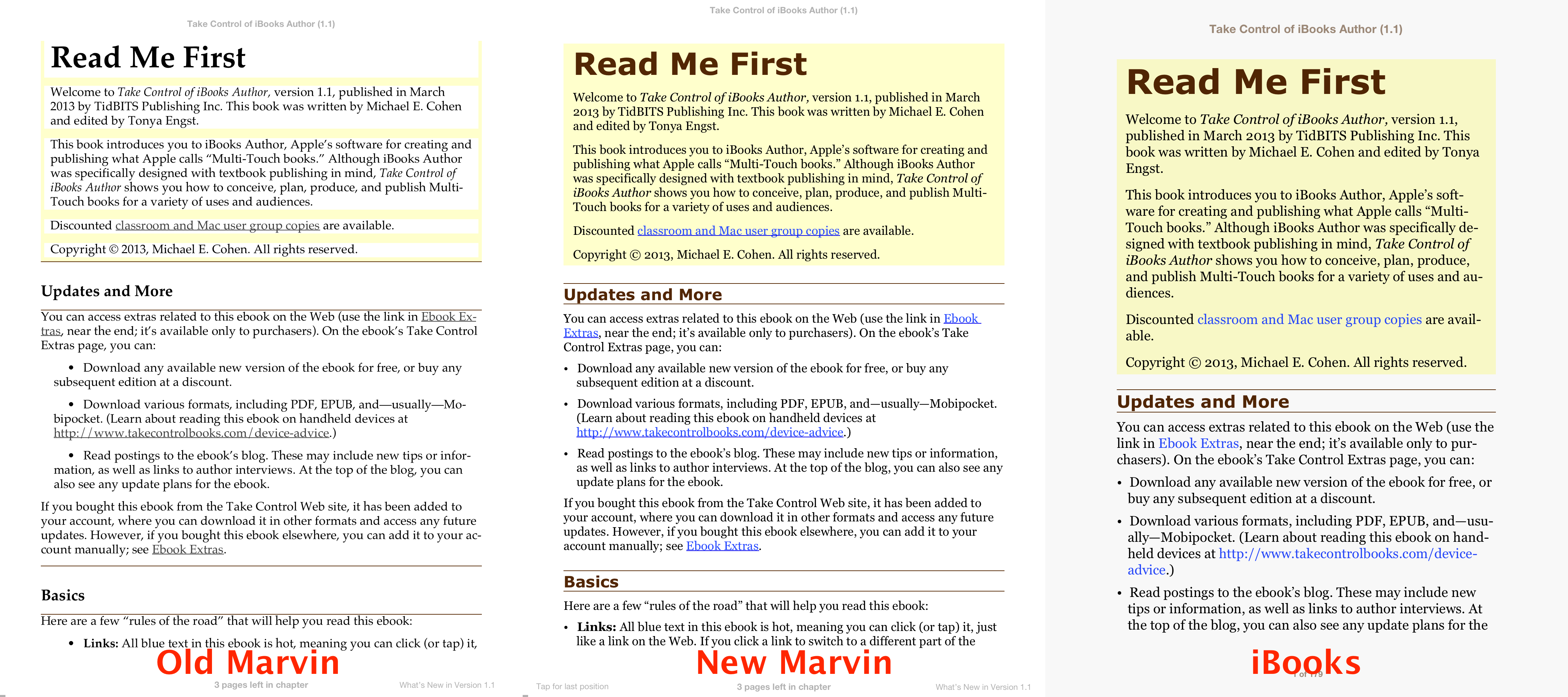

A month or so back, I took a look at Marvin, a free iPad ebook reader app from Appstafarian Limited (see “Marvin the Intelligent Ebook Reader (Almost) Gets It Right,” 10 May 2013), and, while I was impressed by its powerful tools for reading and organizing ebook collections, I was disappointed by its poor rendering capabilities when displaying complex ebooks, such as Take Control titles. I was also dismayed that Marvin made no attempt to respect an EPUB’s publisher-specified typefaces and text colors — although most EPUBs don’t include such specifications, some do, including, as I pointed out in my article, not only Take Control books, but such

best-sellers as J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter EPUB editions.

Within hours of my article’s posting, Marvin’s developer, Kristian Guillaumier, had contacted us at TidBITS. In his email, he noted that he was aware of Marvin’s rendering issues with complex layouts, and he promised that he was going to devote attention to it in the next version of the app.

I am pleased to report that he kept that promise: Marvin now respects publisher layout specifications for any EPUBs that have them. And, as it should be, adhering to those specifications is a user-controllable option: Marvin’s Format pane now has a prominent Switch to Publisher’s Formatting option that you can enable or disable.

Take, for example, the Harry Potter books. While the old version of Marvin could present the books well enough that the reading experience was adequate, the app was unable to deal with such fine touches as the proper placing and sizing of the drop cap that opens each chapter. The new Marvin, on the other hand, when set to use the publisher’s formatting, does a splendid job of it.

Even better, Marvin’s publisher formatting option can even handle the salmagundi of complex formats contained in a Take Control book. Text colors, background colors, bullet lists, horizontal rules, hanging indents — all of which the previous version of Marvin stumbled over badly — are no obstacle to the latest incarnation of Marvin. In fact, if anything, Marvin does a better job of rendering bullet lists than iBooks does. The only shortcoming in how Marvin presents a Take Control book is in the way it presents linked text:

although Take Control books tend to rely on blue text without underlines to present linked text, Marvin still insists on underlining those links — however, Marvin now does display them in the right color. I can live with that.

In my first look at Marvin, I said that Marvin could well become my go-to ebook app just for its toolset alone. Now, with its much improved text rendering, Marvin has earned a place on my iPad dock.

Apple TV Update Adds HBO GO, ESPN, and More

Apple has updated the second- and third-generation Apple TV to version 5.3, adding several new content options: HBO GO, WatchESPN, Sky News, Crunchyroll, and Qello. If you’re not familiar with them, here’s an overview of each service.

HBO GO — With HBO GO, current HBO subscribers can access HBO’s extensive content library and original programming. Unfortunately, you must already subscribe to HBO through a participating cable or satellite provider — cord cutters are not welcome, nor were DirecTV customers, until DirecTV responded to voluminous Twitter complaints. While this has been the subject of much debate online, with television’s current business structure, it’s not likely to change any time soon. However, recent comments by HBO CEO Richard Plepler offer a sliver of hope that it may one day be possible to subscribe to HBO content via HBO GO without having a cable subscription.

Cable providers pay big bucks for HBO, and if HBO sold directly to the consumer, the company might risk being banished from those providers. However, a long-forgotten fact is that HBO used to be a satellite provider itself. Back in the 1990s, my family owned one of the large, old-school C-Band satellite dishes, and we purchased access directly through HBO, via a service called HBO Direct, which included all of HBO and Cinemax’s programming. HBO exited this business in 2001.

Until the industry changes, you have to activate HBO GO through your cable TV provider. Choose Settings within the HBO GO Apple TV app, choose Activate Device, and follow the on-screen instructions. You must then visit a Web site and enter an activation code.

However, HBO GO does feature a few free clips and episodes as a teaser, so the app isn’t completely worthless for cord cutters.

WatchESPN — For sports fans, WatchESPN is an exciting addition, featuring live sports and programming from all of ESPN’s channels, as well as SportsCenter. As with HBO GO, you must have an existing cable subscription from a participating provider to enable it. Or, as I have discovered, Comcast Internet customers have access to it even if they don’t subscribe to ESPN. To activate WatchESPN on your Apple TV, choose Settings in the WatchESPN app, then Verify Your TV Provider. Again, you then have to visit a Web site and enter an activation code.

As with the HBO GO app, there are some free clips available for all, including news highlights.

Sky News — Based in the UK and owned and operated by Rupert Murdoch’s News Corporation, Sky News is a 24-hour news network. The app provides a 24-hour stream of news as well as news clips. While not my first choice for news, it’s nice to have an alternative to the often-spotty Wall Street Journal channel, and it’s absolutely free.

Crunchyroll — Anime fans may appreciate access to Crunchyroll, which is like a Netflix for anime and Asian television. You can sign up directly through the Apple TV for $6.99 per month for the Anime Membership or $11.99 for the All Access Membership, which also includes live-action drama.

Qello — Like to watch concerts on TV? Qello offers HD recordings of concerts and music documentaries. You need a free account even to browse the selections, and to watch much of any of the content, you must sign up for a subscription, which costs either $4.99 per month or $29.99 per year.

WWDC — Though it has been there for a while, you can still view this year’s WWDC keynote from the Apple Events app. However, if you’re a registered developer and want to watch session videos, you’ll have to AirPlay them from Safari or the WWDC iOS app.

What’s Still Missing — While these are all welcome additions to the Apple TV, its selection continues to pale in comparison to the vast array of content channels offered by Roku. For all the talk of how locked-down iOS is, it’s a regular free-for-all compared to the tightly controlled Apple TV, which still lacks support for Amazon Instant Video, PBS, Blockbuster on Demand, Crackle, and many of the hundreds of other channels available on Roku. While you can use AirPlay to send video from many of these services to an Apple TV, it’s a clunky solution for long-term viewing.

However, there might be a third-party solution to the Apple TV’s paucity of content. The developers of the Plex media management software have launched PlexConnect, a clever hack that expands the Apple TV’s selection.

What Apple Data the U.S. Government Can and Cannot Access

On 17 June 2013, Apple released a statement on the recent allegations claiming the NSA has access to user data. In it, Apple states that no government agency has direct access to Apple servers, that the company responds only to lawful legal requests and then provides only the minimum private data necessary to comply, and that sniffing of iMessage and FaceTime conversations is technically restricted due to end-to-end encryption. Apple also revealed that the company responded to 4,000–5,000 requests from U.S. law enforcement this year, predominantly for normal criminal cases as well as assisting in the recovery of lost children, adults with Alzheimer’s disease,

and people potentially at high risk for suicide.

Those of us in the security and privacy world haven’t been overly surprised by the recent media storm. Much of the information on government activities was already known, although the scope (especially of monitoring phone metadata) was a tad shocking. This is a difficult issue to write about because the story continues to develop quickly, the levels of hyperbole are astronomical, and it is highly unlikely the full truth has emerged (if it ever will). But as both the government and tech companies respond, and based on previous knowledge, we can learn a semblance of what’s possible, even if we can’t understand the full scope.

My professional assessment is that we should all be concerned with the erosions of our personal privacy enabled by law and business models, but both the government and private enterprises do still operate within those boundaries. Technically, any information we store with Apple, or nearly any online service, is accessible, for as long as it is stored on remote servers, but it is highly unlikely that any government is sweeping it all up on a daily basis.

What the Law Allows — First, the usual disclosure. I am not a lawyer, I don’t play one on television, and none of my immediate family members are lawyers (just one brother-in-law). But as someone who has worked in global information security for over a decade, I need to be nominally familiar with international legal structures for data privacy.

The first thing to understand is the concept of jurisdiction — companies must comply with the laws in the countries in which they do business. This is a huge pain, but if a company has a business presence in a nation, they have to follow the rules within that nation, or leave. For example, Google still struggles to operate in China due to local requirements to keep all data and make it accessible to the government. Many European businesses cannot legally transfer customer or employee data to the United States due to our lax privacy laws. Amazon builds Amazon Web Services data centers in other countries less for performance reasons, and more to allow

businesses to use the services while meeting local legal requirements.

Apple’s data centers are currently located in the United States. The company has not said how often it responds to legal requests in other countries, but we can assume that, as a minimum, Apple complies with U.S. law and may also be required to release data in other countries, on citizens of those countries, where it does business.

The current laws in the United States will likely surprise most residents. For example, law enforcement agencies state that, under current law, they can access any read email stored for over 180 days on a server without either a warrant or even probable cause. That same interpretation extends to most data you store with any online service that you don’t deliberately protect yourself, since the law says you give up your privacy by not keeping it on your person. Often those companies will fight to protect your data, but their user agreements (those things you don’t read before clicking) usually give them

full access to your data. Also, while phone calls are protected under law, the metadata about who you call isn’t. And none of this applies to non-U.S. citizens, even if your data is only passing through this country.

In intelligence and counterterrorism situations, U.S. government agencies have even more power. They can listen in on phone calls without a warrant if one side is a foreign terrorism suspect. They can obtain secret warrants after the fact, with very little justification required. They can force technology companies, like Apple, to provide specific data for investigations and operations, without allowing firms to reveal that any such request was ever made (ever!). That’s why Apple could state how many law enforcement requests it responded to, but not how many intelligence requests. We still have no idea how much data the NSA obtained from Apple (or any other company).

This puts PRISM and the disclosure that the NSA obtained all Verizon call information in context. Reading between the lines, it looks like nothing more than technology companies responding to perfectly legal requests with the minimum information required. We don’t know the scope of it, and maybe someone is lying or something is classified, but while you might dislike the extent of the law, it doesn’t appear anyone broke it.

What Apple Can Provide Governments — Apple is actually in better shape than many competitors, especially Google. Apple can assist law enforcement and intelligence with two categories of data and a third situation:

- Information you store on iCloud or with other Apple services, like the iTunes Store

- Your location, if Find My iPhone/iPad/Mac is enabled

-

Forensic recovery of information on an encrypted iPhone or iPad, but the security of those products may make that data unrecoverable even with Apple’s help

Open your iCloud preferences to see what data is available, which will likely include any email, calendar events, and to-do items (in iCloud, not your other accounts). Also included: your photos and the metadata (like location) associated with those photos. Your iCloud documents, contacts, notes, and reminders. Your App Store and iTunes Store purchases. Your Safari bookmarks and synchronized tabs. The biggest exposure with Apple is likely your iOS backups, should you back up to iCloud, since backups include everything on your phone.

Compare this data to what Google keeps, including Web searches, Web browsing history (through Google’s extensive ad network), email messages in Gmail, phone calls through Google Voice, events stored in Google Calendar, photos uploaded to Picasa or Google+, location searches in Google Maps, and anything else you do on any Google service.

In its statement, Apple also clarified what it can’t access. Apple doesn’t keep Siri searches or requests, nor does the company retain your location searches in Maps. iMessage and FaceTime are encrypted end-to-end, which means that the data is not accessible on Apple servers.

But it’s not as simple as Apple would have you believe. Apple manages the “root of trust” for iMessage and FaceTime conversation encryption, and Apple could potentially intercept the data using a man-in-the-middle attack, although it is highly unlikely that such capabilities are currently built in. Odds are that Apple’s lawyers would fight such a request to the death since it would involve actual code changes on Apple’s servers and violate its public privacy statements.

Apple may also be using this incident to jab at Google with the statement, “Apple has always placed a priority on protecting our customers’ personal data, and we don’t collect or maintain a mountain of personal details about our customers in the first place. There are certain categories of information which we do not provide to law enforcement or any other group because we choose not to retain it.” This criticism also applies to other companies, like Facebook and Amazon, whose businesses are predicated on providing personalized information to customers.

(It’s worth keeping in mind that just because companies collect data about users, it doesn’t mean that they share that data with anyone else voluntarily. Conspiracy theories abound about Internet companies selling customer data to unsavory marketers, but in reality, customer data is the secret sauce for firms like Google, Facebook, and Amazon — they would no more sell it than Coca-Cola would share the formula for Coke. There’s far more money in building a business around that data than in selling it to a would-be competitor.)

Although Apple doesn’t store location history, it can access your current location. This is likely how Apple has assisted law enforcement in locating lost children and mentally ill adults. As a former rescue professional, I’ve been personally involved in situations where such information could have saved lives.

Lastly, there are rumors Apple can assist law enforcement agencies with speeding up the forensic recovery of data on encrypted iOS devices. This almost certainly isn’t through a back door, but probably by supporting off-device brute force decryption, which still is effectively impossible if you use a sufficiently long passcode. Security and jailbreak researchers are constantly hammering on iOS and Apple’s devices; odds are that they would find any deliberate back door. Besides, such a back door is not only not in Apple’s business interests, but would be a massive potential PR (and possibly legal) liability.

A Lack of Transparency — Without being on the inside, we don’t know exactly how hard Apple or any other technology company fights to protect user data from governments. Businesses need to comply with local laws, but different companies respond in different ways. Google may collect an extensive amount of private user data, but there is every indication that it does its best to minimize government access. Google even provides a real-time Transparency Report of the requests it is allowed to reveal, and has asked the U.S. Attorney General and the FBI for permission to reveal more requests in the Transparency Report.

Apple appears to limit government access as best it can, and Apple collects far less data than many other companies, and only with user permission. If you don’t use iCloud, rely on your own mail servers, and store only local encrypted iOS backups, there isn’t much Apple can provide the government. Plus, FaceTime and iMessage appear more secure than normal phone calls and texts. Any mobile phone can be located physically, even if Apple data is potentially more precise (and your phone provider likely keeps that data for quite some time).

At least, for now. Federal authorities are currently lobbying for government back doors to all online communications services, as they currently have for phone wiretaps. (This would be disastrous, since it is inevitable that hostile governments and online criminals would crack the security of any direct access.) We also lack a clear picture of the extent of current U.S. law and the use of those laws, since companies like Apple and Google are not allowed to disclose how often the U.S. government uses such powers, and the government is not revealing how effective such information is in stopping terrorism and other crimes.

While the United States is in the headlines, we have even less insight into the behavior of other nations, some of which require Internet service providers to keep metadata or even all network traffic for years in case it’s needed for an investigation. Lastly, remember that, in general, any online company you provide data to can look at it whenever it wants — I explained how you can determine if this is possible in “How to Tell If Your Cloud Provider Can Read Your Data” (9 April 2012).

Thus, the good news is that Apple appears to provide the government as little data on us as possible, and has practical limits on what is even available. The bad news is that we have nearly no insight into what the U.S. government is doing on our behalf, even if it is within the boundaries of existing laws that all too few understand.

Pondering the Social Future of Wearable Computing

The battle for our technological hearts and minds is moving to our wrists and faces. Everyone seems to be racing to put a computer in your watch, while Google is leapfrogging several body parts to put one on your face. Meanwhile, the media have deemed this a hot story, so headlines are rife with predictive analysis and rumor, both of limited value.

Naturally, part of the breathless coverage of these devices — most of which still don’t exist — is the steady stream of pundit predictions about which device will be The One to Rule Them All, as well as which features “must” be included in order to provide their manufacturers Market Dominance for All Time. But the fact is, no one has any clue which devices will be successful, or if any of them will.

That’s because it’s not the companies that will decide what our next toys will be. It’s not even the early adopters who will, no doubt, purchase them in droves.

It’ll be everyone else.

Normal Is Deeply Weird — Consider your smartphone for a moment. I would say, “Take out your phone and look at it,” except that something like half of you are already doing just that while reading this.

If you’re older than 20, you probably remember a time when cell phone minutes were precious and sparsely used, like “long distance calls” in black-and-white movies. If you’re north of 30, you’ll remember when even having a cell phone indicated that you were fantastically wealthy, perhaps due to unethical reasons. Compare that with 2013; while I’m not actually aware of a cereal box that contained an Android phone as the free prize, I can’t discount the possibility. (However, Entertainment Weekly did include one of sorts in an advertisement.)

Unlike most technological changes, we can actually date when this one began: 29 June 2007, when the first iPhone shipped. Before then, it was extremely uncommon for the average Joe to have the Web in his pocket, and I can say that with assurance because I was one of those outcasts. Prior to the modern era of cellphones, you were considered irredeemably weird if you carried around a Sony Ericsson P900, knew how to send email with a Sony Ericsson T68i, or attempted to view Web pages on a Palm VII. (Arguably, attempting to surf the Web on a Palm VII also made you irretrievably masochistic.)

With the release of the iPhone — and with the equally important availability of Android phones at much lower prices — what was once viewed as somewhere between “bizarre” and “scary” has become the norm. (And if you don’t believe me about scary: the first time I held a conversation on a phone headset, a woman at a supermarket who couldn’t see the wire made eye contact and then literally ran away from me.) The division between “bizarre” and “normal” is the demilitarized zone between the early adopter and the general public. It’s commonly understood that early adopters are willing to pay more money and jump through many technical hoops attempting to get their bleeding-edge, wicked-cool devices to work.

More interestingly, they’re also willing to look rather silly doing it.

That is, using technology in public is a social action. An early adopter has to be willing to attract attention, and needs the mindset that “they’re interested in my technology” rather than “they think I’m a schmuck,” regardless of what the truth of the situation might be. Any technology that makes the move from early adoption to general usage has to normalize the behavior of using it.

But the fascinating thing about the shift from “outlier” to “normal” is that normal is a very wide umbrella, which has many holes in it that allow the rain to come in.

Dinner with Your Smartphone — You’re out to dinner with a companion: perhaps a spouse, coworker, friend, or date. Naturally, you both have smartphones, or at the very least, some handheld gadget that connects you in ways that would have been unimaginable in 1993.

Many people do something, consciously or not, with their smartphone when they sit down. If it’s in a back pocket, it has to be moved so as not to test the tensile strength of Gorilla Glass. If it’s in a front pocket, likewise to avoid denting a hipbone. Phones in purses may be shifted to avoid theft or scratches; phones in a jacket pocket may be self-consciously removed to avoid affecting its drape.

What do you then do with the phone? Do you turn off the ringer? Turn on the vibrator? If you set it down on the dinner table, is it face down or face up? If the phone beeps, rings, or rattles over the course of the meal, what’s the acceptable response to its clamor for attention?

Here’s the thing: it’s a trick question. Your answers to the previous questions have nothing to do with the phone, and in most cases, very little to do with your preferences. They were answered earlier, when I glossed over with whom you were eating and where you were. The social norms of two people out on a date are entirely different than the same couple five years later; two coworkers react differently than when one is eating with her boss.

And these norms have dozens of permutations and exceptions. It’s nearly universal that when a phone unexpectedly rings or buzzes loudly, it’s followed by the dive for the button that silences it. But when do you glance at the screen to see what caused the alert, and when don’t you? If you’re having dinner with an old friend or significant other, these might be explicitly negotiated. More commonly, they’re simply assumed, as are the reactions of the people around you. Expect disapproving stares when your phone rings at a funeral or during a movie; on the other hand, if you’re a surgeon, and known to be a surgeon, you’re likely to get a pass.

In the parlance of anthropologists, the culture surrounding mobile phones is “thick”: a set of rules and norms that vary depending upon who you are, whom you’re with, where you are, and dozens of other factors that are all instantaneously processed and coded.

These rules extend to how people near you are allowed to respond. People may stare at you if you talk constantly at Starbucks, but it’s rare that they’ll take your phone and dunk it in your latte. Talking constantly on a cell phone is considered rude but not transgressive; compare that with watching an explicit episode of “Dexter” or an adult movie on a MacBook in public, which might inspire a stronger reaction.

The amazing thing isn’t that we’ve developed these rules; similar rules exist for everything you do during a meal, ranging from the proper use of straws to how you might address your waiter. The amazing thing is that we’ve developed such a thick set of rules for handheld Internet computers after only five years.

That’s the buzz saw that smartwatches and Google Glass have to avoid if they’re going to become successful. It’s not about the technology, and it’s not about the features; it’s about the public act of using them, and whether and how social norms will shift to accommodate them.

Screens 3.0 — Smartwatches are a technology with which nearly everyone has some experience: a wrist-attached gizmo that displays some interesting bit of information, and might demand your attention with a pre-set alarm. That’s a decent description of dumb watches for the past few decades. Watches are also a cultural artifact, with rules about how and when they can be used — ask anyone who has been caught glancing at one during an event that someone else thinks should be captivatingly interesting.

The possibility that you’re smiling at the memory of being this person, or frowning in annoyance about the time someone accidentally demonstrated boredom, indicates the universality of this cultural trope. Glancing at a watch signals impatience and boredom, but only because of what a watch does. You only look at a watch when you’re counting the minutes; everyone else knows that there’s no other reason to look at a watch if you’re not ten meters under water. When a watch might display very different information, the universal understanding of this gesture will change — but much more slowly than the technology does.

Picture that same dinner in three to five years. Your dinner companion glances at his watch — to check the time? Check a Facebook update? Read a text message? Unlike a buzzing cell phone, a watch can be expected to be right next to the skin, so its vibrator may be low-powered and undetectable to anyone but the wearer. You might not know if your companion is choosing to do this or responding to an alert. Does that make a difference? Does the content of the alert make a difference?

Unlike a smartphone, watches are difficult to remove. That is, you can put a phone away, but have you ever taken your watch off in public? Most people don’t take them off at all; some folks even buy waterproof watches so they don’t need to remove them in the shower. Presumably, a smartwatch will allow you to silence its buzzers and alarms just as a smartphone does, but since a watch can alert you more covertly than a phone, turning it off is similarly a more private act. Wear a smartwatch, and anyone with you is likely to have no idea how connected you are — and may draw social conclusions about you based on the wrong inferences.

If a watch is a potential minefield, let’s move the smartwatch to your face.

Google Glass is possibly the worst nightmare of people who believe that their importance is measured by the amount of attention they’re receiving — which is to say, the entire human race. Glancing at a watch may indicate boredom, but reading a smartphone screen screams, “what’s on here is more interesting than you are.” That’s why we have so many social cues that dictate when smartphones are to be left unloved in our pockets. Glass removes not only the need to physically handle a phone to be electronically entertained, but also the cues that allow people around us to know what we’re doing.

Then there’s the issue that Google Glass includes a video camera and microphone that can be activated by winking at it. Many concerns have been raised by the privacy community (of which I consider myself a member) that Glass can record audio and video when it would be inappropriate to do so. Google Glass supporters have fired back, stating that such surveillance can already be accomplished with existing technologies. And even I have given instructions for creating such devices in “iOS Hearing Aids… or, How to Buy Superman’s Ears” (8 February 2011).

But that’s the point. If you own a spy camera disguised as a pen or a hat, you’re either James Bond or you’re a creep. There’s no socially acceptable middle ground that allows you to walk around in public with a spy pen; just having that technology classifies you as a certain kind of person, and one who should probably be kept away from children and cats. On the other hand, everyone has that technology in their phone; you only get classified as a creep if you do creepy things with it. Putting video cameras into every phone not only gave more people the opportunity to be creepy — it also moved the bar for the definition of creepy, as merely owning the technology is no longer sufficient to qualify

you.

Why is a spy pen different from an iPhone? I suggest that it’s because the spy pen has only one function: surveilling people without their knowledge. Likewise, the iPhone has surveillance technology, but its widespread adoption makes it difficult to use without tipping off the subject of a video. Google Glass creates a middle ground: a technology that does allow for discreet surveillance, but also has alternate functions that “excuse” its usage in public.

The fundamental issue, then, is that Google Glass allows for surveillance, and the primary barriers against it are social norms. You have to trust a Glass-wearer that he doesn’t have the camera turned on for recording or live uplink to the Internet. This is in contradiction with the norm that anyone who has such technology is inherently less trustworthy; what’s questionable is whether the norm for spy pens will be applied to Google Glass, and if so, how long that norm will survive.

The Cost of Surveillance — The last twelve years have been eye-opening, and not in a good way, for those of us who have been banging the privacy drum as a social issue. Speaking as a long-time activist, I’ll summarize the last thirty years of privacy activism:

- Computerization and big data begin to give private corporations far more information about their customers than ever before. This is also a concern when used by repressive governments, but activism is muted in Western nations as it’s presumed that legal protections will prevent individual and collective monitoring.

- Governments begin to attempt to outlaw or restrict some technologies (specifically strong encryption) while expanding their abilities to monitor electronic communication without going through protective channels, such as requiring a warrant. Post-9/11, this trend becomes an avalanche, making camera surveillance and big data processing the norm rather than the exception.

-

Most importantly from the perspective of social norms, thinking changes about being the target of surveillance. It was formerly “unsurveilled unless suspected guilty” — a presumption that the government, at least, required a reason to track your actions and movements. That has changed to “I have nothing to hide,” which switches the onus of action from the watcher to the target, while arguing that most decent targets should, in fact, be perfectly OK with this.

The corollary to these shifts: I think there used to be a universal perception among privacy activists that at some point, some encroachment on privacy would be the straw that broke the camel’s back, causing a massive uproar that created stronger protections. And in fact, this happened: you can rest assured that your videotape rentals are safe from prying eyes. For everything else, though, a lack of concern is socially normative, unless of course you “have something to hide.” Why else be concerned?

The problem with this comes when we consider social norms about shame and transgressive activities. Tyler Clementi and Rehtaeh Parsons were both driven to suicide after video of their “transgressive” activities were circulated on the Internet. In Clementi’s case, he chose to kiss a man; in Parson’s, she was attacked and raped by multiple assailants.

It has been quite a long time since American and Canadian culture viewed suicide as a justifiable action following homosexual behavior or being a rape victim, but our norms about promiscuity in general and resulting video evidence are still several decades behind our actual actions. I doubt I’m alone in saying that whatever my friends do behind closed doors is their business, while at the same time, I’m certain that none of them are the “type of person” who have nude videos of themselves on the Internet.

What “type of person” is that? Logically, it’s potentially anyone who’s ever been nude with the lights on; that’s the set of all people who might have chosen to film and circulate their videos, or who might have had this done to them without their knowledge. Ergo, my thinking about this personality type is rather illogical.

What’s particularly telling about this example is that I had to switch to sexual activity to discuss a shameful or transgressive act that I thought most readers could relate to. Few people would be happy if their GPS data showed them going to a bordello while on a business trip to Reno; most married people would rather not have their GPS records correlated with their coworkers to show they were both in a hotel near the office at noon. But there might be entire categories of shameful activities that I’m socialized to ignore, and won’t notice until the first case occurs. (Arguably, the exceptionally tragic aspect of the Rehtaeh Parsons case is my belief that “being raped” was left behind as a reason for shame decades ago.)

What Google Glass portends is a future where such surveillance is (a) imposed on its targets without their control, and (b) in the hands of private citizens. To my way of thinking, it’s currently a bigger but different issue when a government with the power of prosecution has such data. In fact, widespread surveillance of the government is a useful check on its abuse of power.

But the problem with putting this in the hands of the general public, not to put too fine a point on it, is that some small percentage of the general public are bastards. The norms we develop about appropriate use of the technology will be broken, and the norms we currently have about people being “caught on film” will take a long time to catch up to the realization that it could be anyone.

Where might we be headed if we don’t take the reins of our cultural and legal environment? One possibility is a future where we can be placed under government scrutiny for saying the wrong thing or associating with the wrong people; one where we can be shamed in public if we aren’t self-censoring our private activities at all times. The problem with this is that the red line of transgression moves all the time; the wrong person, the wrong statement, and the shameful act may be very different ten years from now, but our data probably will live longer than that.

Placing Bets — It’s easy to presume from the prior discussion that I’m opposed to video cameras in general, and Google Glass in particular. I’m not; I would have gotten myself into the private Glass beta if the price weren’t ridiculous, and it’s a safe bet I’ll be an early adopter of whatever comes down the pike in 2014. I’m extremely concerned about what happens when most people are wearing Glass-like devices — but I think the solutions to this are legal protections and a more actively evolving culture about whom we deem to be “bad people.”

That said, I can make a few predictions about where the field will go, based on the cultural observations I’ve made here, and on how we’ve already adopted technologies like smartphones, GPS, and webcams:

-

Smartwatches are likely to become standard sooner than Google Glass. We’re already comfortable with handheld screens, and there’s little question than many people do want to get text messages and notifications on their wrists. The questionable part is whether our cultural norms will change to make smartwatches acceptable. My guess is that they will, but not without a great deal of kicking, screaming, and letters to relationship advice columnists. The interesting things to watch, so to speak, will be whether there are places and times when smartwatches will be considered rude; likewise, widespread adoption of smartwatches might expand the realm of places where using a smartphone more overtly is socially unacceptable.

-

Google Glass is ultimately what’s next, but it might be too soon — the Newton of 2013. A wearable heads-up display has been part of science fiction for decades, and among a certain part of the viewing and reading public (of which I also consider myself a member), the response has been “that is so damn cool.” The problem is that Google Glass stretches too many social norms, possibly past the breaking point. In its first generation, Glass is immediately recognizable; future models that make Glass less obtrusive might make the technology fall more squarely into the creepy spy pen category, not less. I reluctantly believe that video cameras in watches and headwear will do little to slow the adoption of such

devices; on the other hand, their unique ability to follow us soundlessly into bedrooms and private areas (and instantaneously broadcast that information out) could extend the creepy definition to them in a way that it has not extended to smartphones. -

The unsolved problem with both of these technologies is the control mechanism. It has become socially acceptable to have a brief phone conversation in public, but it’s not generally kosher to use Siri or voice dictation. That’s the primary way to control Google Glass, and probably the way you’ll do complicated things on a smartwatch. (Unless there’s a major breakthrough for user interfaces on a two-inch square surface.) I think voice control of smart devices is shortly going to become much more common and will generate new norms of public behavior; I wouldn’t be surprised if, just as we have the “quiet car” on Amtrak, we might soon have “quiet” cafes and restaurants.

-

Where I expect Apple to dominate is in pushing this out of the early adopter phase and into the mainstream. Apple will do the heavy lifting of coming up with a useful (by general standards), underpowered (by geek standards), and simple (by your parents’ standards) way of interacting with your other Apple devices through a watch. That’s not to say that I expect Apple to “win” the smartwatch competition automatically, only that it’s Apple’s involvement — and perhaps only Apple’s involvement — that transitions a smartwatch from “geeky toy” to “the kind of thing you see everyone wearing the airport.”

FunBITS: Badland for iOS

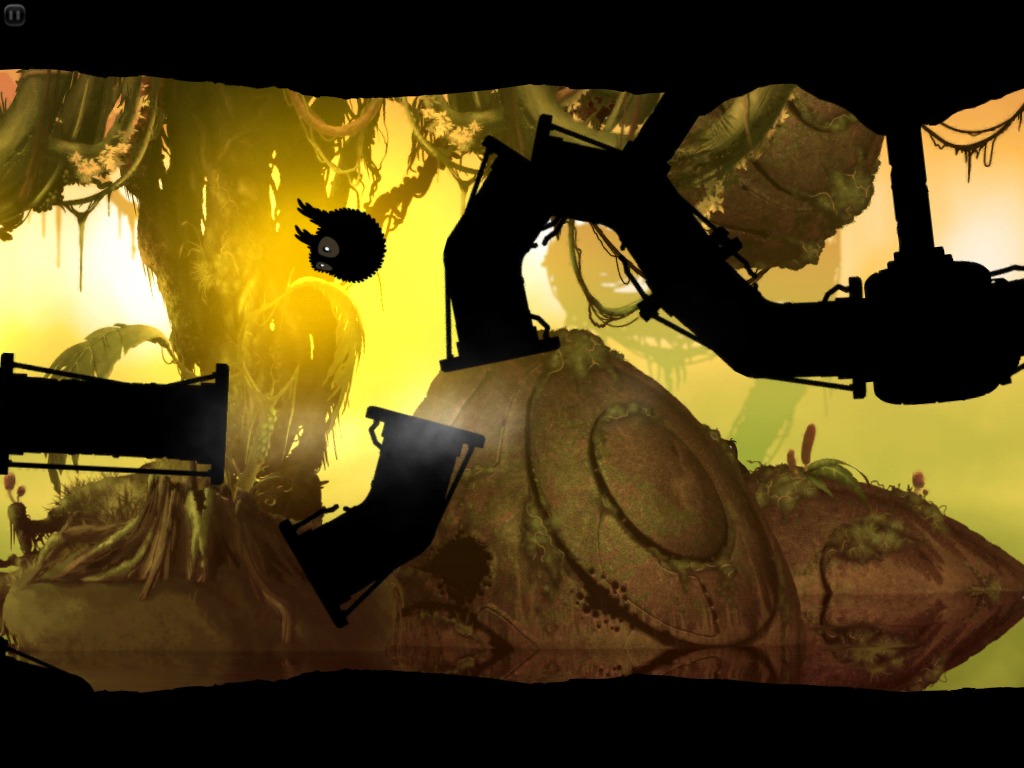

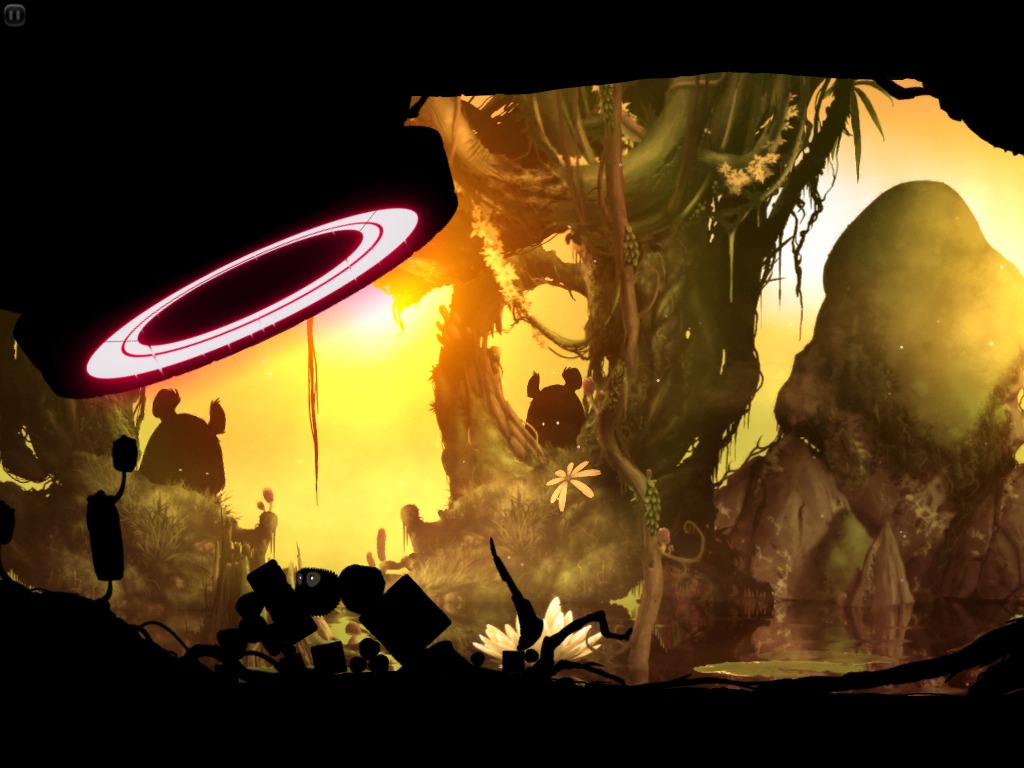

Every year, I love to see which apps win Apple Design Awards, as the awards often turn my eye to overlooked gems. This year’s winners were no exception, highlighting a game that I sadly missed when it debuted in March 2013: Badland by Frogmind, which normally costs $3.99, but as of this writing is on sale for $1.99, and works on both iPhone and iPad in the App Store.

Badland is, at its basic level, an endless runner — a game genre popularized by the iPhone — where you control a character that is constantly running, taking a break only to jump or sometimes fire a gun. It’s a genre born of the iPhone’s inherent limitations, but Badland takes it to a whole new level.

The game is dark, yet gorgeous, making heavy use of shadow, contrasted with bright, yet dour, tones. Visually, it resembles the dark World of Goo, or a Tim Burton movie. You control a, well, I’m not quite sure what, as the game leaves the setting and story completely to the player’s imagination. But whatever the protagonist is, it resembles a cross between a fat hedgehog and an oil-soaked tribble.

The character, for lack of a better name, doesn’t walk, run, or even fly exactly, but awkwardly flutters up and forward as you hold your finger on the screen. Physics plays a big role in the game, and so does gravity, so if you lift your finger off the screen, the character quickly plummets to the ground and to a dead stop. Literally dead in this case, because as soon as you’re ejected from an oily pipe at the start of the level, the screen starts scrolling to the right, and if you don’t keep up, you’re dead.

In typical endless runner fashion, you have to keep moving and dodging obstacles to make it to the end of each of the game’s 50 levels. But there’s more complexity here than jumping over gaps or blasting zombies with a shotgun. Instead, you have to solve puzzles — pushing levers, tree branches, rocks, and steam pipes in just the right way to make it through in time. All while dodging saw blades, thorns, and bouncing rocks.

There are power-ups, both to help and hurt you. Some make you tiny, some make you huge, some help you cling to surfaces, and all affect gameplay in notable ways. When you’re small, you can squeeze through tight spots, but are out of luck if you need to push anything. When you’re large, you can easily push obstacles out of your way, but are slow and too big to make it through small gaps. Sometimes it’s in your best interest to skip a power-up, as accepting it might make the next portion of a level impossible. And

sometimes, you need to be both large and small to get through a section, and that takes careful management of your clones.

As you move through the level, you can pick up clones of yourself, and the score for each level is based on how many clones you manage to bring to the end intact. However, that’s harder than it sounds, since navigating through the game’s puzzles and traps with a horde of clones can be a challenge, and often you have no choice but to sacrifice a few to survive. Sometimes you have to carefully split them up, as some puzzles will require big characters to activate something to create an opening that only the small ones will be

able to enter.

Badland is a tough game, one that takes trial and error, and often repeated execution to survive. While challenging, it won’t cause you to hurl your iPad through a window in frustration. Each level has numerous checkpoints, so if at first you don’t succeed, you can try again quickly instead of fighting your way back through a level. Also, the controls are responsive, so the only frustration you experience is due to your own failings. In fact, in spite of its darkness and difficulty, Badland is actually pretty relaxing. The chill jungle environment and sounds help with that, even if it’s the sort of jungle that you’d be lucky to escape in one piece.

There is a multiplayer component of Badland that supports up to four players, but it works with only one screen — networked play isn’t supported. Multiplayer games take the form of a race through a level — first to reach the end or the last alive wins. If you’re dexterous enough and curious about the multiplayer levels, you can control more than one character at once.

Most iOS games are stripped-down console games, cram so much into the screen that it’s impossible to control, or are simple games that would work on any platform. Badland is true to the device, offering an identical experience on both iPhone and iPad, even including flawless iCloud syncing of game progress, which isn’t as common as you might think. It never feels like a feature-limited port, nor is it designed for the lowest common denominator. Yet, it is balanced enough to be enjoyable by casual and hardcore gamers alike. If you’re looking for a rich, unique gaming experience for your iPhone or iPad, Badland is worth a download.

TidBITS Watchlist: Notable Software Updates for 24 June 2013

Mellel 3.2.1 — Less than two weeks after the release of Mellel 3.2 (12 June 2013), developer RedleX has released Mellel 3.2.1, which fixes compatibility issues with Mac OS X 10.5 Leopard. The word processor update has also restored support for automatic baseline shift adjustments for MathType equations and features smarter application of default languages with new documents. ($39 new from RedleX and the Mac App Store, free update, 105 MB, release

notes)

Read/post comments about Mellel 3.2.1.

Java for OS X 2013-004 and Java for Mac OS X 10.6 Update 16 — Apple has released Java for OS X 2013-004 for OS X 10.8 Mountain Lion and 10.7 Lion and Java for Mac OS X 10.6 Update 16. Both update Java SE 6 to 1.6.0_51, but they have different effects on the built-in Java browser plug-in. The update for Snow Leopard enables per-site control of the plug-in, while the update for Lion and Mountain Lion removes Apple’s Java plug-in entirely, directing you to download Oracle’s plug-in if you need it. Apple’s security page

notes that these updates address several critical vulnerabilities that could cause arbitrary code execution outside of the Java sandbox, as well as 33 other vulnerabilities. The updates are available via the App Store app or Software Update and direct download, and Apple reminds you to quit any Web browsers and Java applications before installing either one. For more information about Java on the Mac, see “FlippedBITS: Java, JavaScript, and You,” 2 May 2013. (Free, 64.01 MB for 2013-004 and 69.48 MB for Update 16)

Read/post comments about Java for OS X 2013-004 and Java for Mac OS X 10.6 Update 16.

TweetDeck 3.0.2 — Twitter has released TweetDeck 3.0.2, which offers a notable interface redesign. A new icon sidebar on the left side replaces the previous top-mounted controls, offering a pair of buttons for creating a new tweet and for searching, and then a stack of buttons for each of your columns, plus three buttons at the bottom that expand the icons into text, open the list window, and access settings. You can finally rearrange columns by dragging their sidebar icons, and clicking a column icon focuses on that column, scrolling the main window as necessary. Some additional interface

refinements are coming soon, but haven’t yet appeared in the Mac App Store. Once the next version arrives, you’ll be able to drag grab handles to rearrange columns as well, clicking a column icon will bring columns to the left edge if fewer than four columns are showing, and clicking a second time on a column icon will scroll that column to the top. (Free, 1.4 MB, release notes)

Read/post comments about TweetDeck 3.0.2.

Hazel 3.1.1 — Noodlesoft has released Hazel 3.1 with a ton of changes to the file cleanup and processing utility. New features include support for uploading matched files via FTP, SFTP, and WebDAV; the capability to use patterns to match against and extract the contents of PDF and certain text file types; a custom date token that can match dates in text; descriptions of rules for later reference; an option to copy over an existing folder structure; and an option to avoid overwriting existing files. There are also a number of user interface changes that should make Hazel easier to use. Under the hood, Hazel 3.1 has

optimizations to reduce unnecessary multiple passes on file processing, added delays before trashing duplicate files and deleting too-large files, and improvements in metadata handling that should improve performance. A variety of bugs have also been fixed, most of which are pretty specific, though Noodlesoft closes the release notes with “honey bunches of fixes.” A quickly released version 3.1.1 addresses a couple of crashes and other bugs. ($28 new, free update, 7.5 MB)

Read/post comments about Hazel 3.1.1.

ExtraBITS for 24 June 2013

This week in ExtraBITS, Marco Arment calls for the end of the App Store’s “top” lists, the Computer Desktop Encyclopedia is now free for all, a musician evaluates the forthcoming Mac Pro, AT&T customers will now receive iOS 6 government alerts, and the iPhone 5 has finally come to Virgin Mobile. Speaking of eagerly awaited things, HBO GO has at long last appeared on the Apple TV, and The Verge has the story of what it took to get there. While many Mac users are looking forward to the superior battery life of the new MacBook Air, some have been disappointed with Wi-Fi problems. Finally, the new MacBook Air and other WWDC news was the topic of Adam Engst’s appearance on the Tech Night Owl Live podcast.

Looking for a Better Computer Encyclopedia? — David Pogue of the New York Times writes about the Computer Desktop Encyclopedia, an online encyclopedia of computer terms that has lost corporate licenses in the wake of Wikipedia’s popularity. In response, creator Alan Freedman has now made his encyclopedia free at computerlanguage.com. If you’re researching a computer term, give it a try, since its definitions can be better written and more comprehensible than Wikipedia’s sometimes torturous text.

New MacBook Air Owners Complaining of Wi-Fi Issues — Gizmodo reports that many owners of the new 2013 MacBook Air are complaining of lost Wi-Fi connectivity, requiring a reboot to reestablish the connection. The issue is reportedly worse when the MacBook Air is on a desk, which might indicate a hardware issue. So, if you’re thinking of buying a new MacBook Air for its significantly improved battery life, perhaps hold off until more is known about this Wi-Fi issue.

HBO’s Long Road to Apple TV — The Verge has a compelling account of the barriers HBO had to hurdle to get its content on the Apple TV. One was technical, including efficient encoding of the entire HBO library and writing the software, which was made possible by a new HBO development center in Seattle. The other was political — cable companies are distrustful of online distribution and set-top boxes.

iPhone 5 Headed to Virgin Mobile — Pre-paid cell phone users rejoice! The iPhone 5 is finally headed to Virgin Mobile on 28 June 2013. Virgin Mobile, which runs on the Sprint network, will be selling the 16 GB iPhone 5 for the unsubsidized price of $549.99 at RadioShack and other participating retailers. The iPhone 5 will be compatible with Virgin Mobile’s Beyond Talk plan, which starts at $35 for 300 minutes of talk, unlimited texting, and unlimited data (throttled to 256 Kbps or lower after 2.5 GB of monthly usage), with a $5 monthly discount for customers who enable

automatic payments.

Adam Engst Discusses WWDC on the Tech Night Owl Live — Adam Engst joins host Gene Steinberg for a lightning discussion of the announcements at WWDC, focusing on the low-level improvements to Apple’s operating systems, the battery life of the new MacBook Air models, what will happen with 1Password after the release of iCloud Keychain, how apps will support both iOS 6 and iOS 7, the Mac compatibility matrix for OS X Mavericks, and more.

AT&T Users Finally Getting iOS 6 Government Alerts — AT&T is pushing out an update to iPhone 4S and 5 owners to enable the government alerts feature that was introduced in iOS 6, a capability that has been available to Verizon customers since September 2012. The alerts are part of the FCC’s CMAS (Commercial Mobile Telephone Alerts) initiative, and include severe weather alerts, AMBER alerts for abducted children, and Presidential alerts. All but the Presidential alerts can be disabled in settings, and none of the alerts count against data or messaging limits.

What the New Mac Pro Means for Audio Pros — Peter Kirn, a musician, inventor, and teacher writing for Create Digital Music, has penned a treatise on how the forthcoming Mac Pro will affect musicians and audio pros. It’s a lengthy read, but worthwhile for anyone in the field. Much of his examination revolves around the new Mac Pro’s lack of interior expansion. While many pros will be disappointed at the lack of PCI slots, Kirn argues, “…if you want to take the material you worked out in the studio and bring it on the road with you, you can

unplug a Thunderbolt accessory and use it with your laptop. It’s hard not to see that as a very good thing.”

Marco Arment Calls for the End of App Store “Top” Lists — Marco Arment, creator of Instapaper and The Magazine, is arguing for the end of the “top” lists in the App Store: top paid apps, top free apps, and top grossing apps. His reasoning is that those lists simply help top sellers stay on top, as many people rely entirely on the lists for app discovery. Also, he argues that the lists encourage cheap, shallow apps, and says that the system itself is easy to game. More human curation would help, as would better search and discovery within the App Store.