For many years, I’ve used an old Mac mini connected to a large external hard disk as a general-purpose network server. It was where all my music and movies were stored, but it also served as overflow storage and an occasional testbed for beta software. It has worked, mostly, but has always felt clumsily patched together. As my storage needs increased, and as I was preparing to write my book Take Control of Your Digital Storage, I realized I needed something more robust, like a NAS (network-attached storage) device.

When I asked a technical friend for his opinion on which kind of NAS to buy, his response mirrored mine (and perhaps yours, too). He had been thinking about getting one, but the sheer number of variables involved kept him from making a purchase.

A NAS itself typically looks like an unassuming largish box, sometimes containing just a single drive, but more often with two or more drive bays into which you insert bare hard drives or SSDs, making it possible to upgrade the overall storage over time by using higher-capacity drives. What makes it special is that it’s also a computer in its own right, with a processor, operating system, and RAM to handle all its tasks.

The NAS connects to your local network via Ethernet cable, making it available to everyone else on the same network. And in many cases, you can access the NAS when you’re outside the local network. If you arrive somewhere with your laptop and realize that an important file isn’t on your computer’s internal disk (or even if you’re on the couch downstairs and the file is on the NAS in your home office upstairs), it’s no problem; that file is available just as if its drive was directly connected to the computer.

Several vendors sell NAS units, such as Synology, QNAP, Drobo, and WD. And among those, you’ll find models designed for personal use, for small offices, and for industrial applications.

If you think hard drive specs are eye-glazing, wait until you wade into the technicalities of NAS devices. Price is always a consideration, and some manufacturers mix and match components to hit price points—a unit might have four drive bays instead of two, for example, but use an older processor and offer less RAM. But that also means you can likely find something in your budget that performs the tasks you need.

NAS vs. External Drive

Before we step through the features themselves, let’s consider the reasons to use a NAS instead of a standard external hard drive. Some common reasons include:

- More storage: A NAS can offer more storage than a single external drive. I put off buying a NAS for a long time because hard drive capacities kept expanding to fit my needs (thanks, manufacturers!). Although I knew a NAS could provide more than what a single drive offered, it was easier to bump up the storage and go with what I was familiar with. That started to get expensive, though. When your storage needs outpace individual drive sizes, a NAS with several drive bays becomes more appealing.

- Expandable storage: A NAS is designed to grow with your data needs. When an internal hard drive in a NAS fills up, you can easily replace it with a higher-capacity one. I could go through my office and count the current and retired external hard drives, with their enclosures and cables and power supplies, but that would be too depressing.

- Protection against drive failure: Related to the above, it’s no fun when hard drives fail—and they do fail. Some NAS devices are built as RAID 1 or RAID 5 arrays, or as proprietary variations that incorporate the same technology, to mirror data such that if a disk crashes, you don’t lose data. And if that does happen, you can keep using the NAS volume while swapping out the bad drive.

- Remote access: If you primarily work on a desktop computer that doesn’t travel, having a high-capacity external hard drive plugged in all the time is no trouble—for that computer. Connecting to the data from a laptop, or another computer on the same network, is made easier with a NAS. It doesn’t rely on a desktop computer to share its contents, as is true of a traditional hard drive, because the NAS is the computer. This point is doubly important if you’re nowhere near your local network, such as while on a trip to another city, and need access to files.

- Streaming media: Many NAS devices include software for streaming video and audio stored on the drives. If you’ve built up a home library of movies, whether recorded yourself, ripped from DVDs, or downloaded, a NAS makes it easy to stream them on TVs, tablets, phones, and other devices.

- Business services: Although these uses are outside the scope of this article, many NAS devices can be set up as Web or email servers, cloud servers (like having a private version of Dropbox), and more. Some businesses and individuals prefer to have full control over these services instead of relying on Dropbox, Gmail, and others.

- Network backups: With a lot of storage and a constant presence on the network, a NAS can be a good on-site destination for backing up local computers. For example, my wife’s MacBook Pro is usually in our living room, and she doesn’t want a hard drive dangling from it for Time Machine backups. Instead, her data is backed up over the network.

NAS Features

I’ve arranged the following specs based roughly on their importance, although you may have different priorities, like hardware transcoding for streaming movies.

Number of Drive Bays

Packing more drives into a NAS gives you more storage, but there’s more to it than that. A two-bay NAS sounds like a good starter, and it’s certainly affordable. But remember that a typical NAS RAID configuration is set up with one drive for data and the other for redundancy—RAID 1 in a two-bay model.

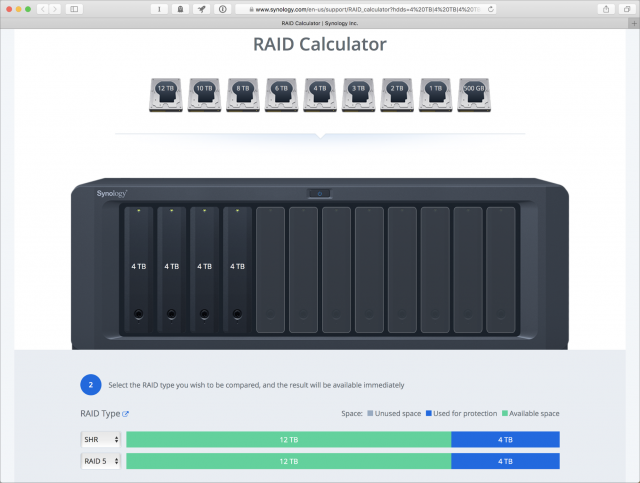

If you populate it with two 4 TB drives, for example, you end up with 4 TB of usable storage space and 4 TB of mirrored protection. To increase the capacity, you could buy two 8 TB drives to replace the 4 TB drives, giving you 8 TB of usable storage and 8 TB of protection.

With a four-bay model, you could instead add two more 4 TB drives (which cost less per terabyte than 8 TB drives) to fill out the slots and end up with 12 TB of usable storage and 4 TB of protection in a RAID 5 configuration (or similar proprietary setup) for greater data redundancy and failure protection.

(In a four-drive RAID 5 configuration, redundancy comes not from mirroring, but from recording parity information—small bits of extra data that are added when copying files to ensure that the operations were successful—which is why you have more usable storage compared to redundant storage in this scenario.)

If you’re unfamiliar with how storage and RAID levels interact, check out Synology’s RAID Calculator. Even if you don’t end up buying a Synology NAS, it’s helpful to spec out how various drive capacities work under different RAID levels.

Ethernet

The “network” part of network-attached storage comes from connecting via Ethernet. In most models, that refers to Gigabit Ethernet (GbE), capable of theoretical transfer speeds of 1 Gbps (gigabits per second). Some more expensive models provide 10 Gigabit Ethernet (10 Gbps) connections. Faster is always better, but consider that the iMac Pro is currently the only Mac that supports 10 GbE directly; you can buy adapters to achieve those speeds with Thunderbolt 3-equipped Macs. Also, 10 GbE networks require Ethernet switches that can handle the speed. My recommendation is that if you think you’ll want 10 GbE in the future, buy a NAS that either has 10 GbE built in or available as an option; some NAS models include PCIe expansion card slots that accept such upgrades.

Another Ethernet-related consideration is how many ports are included. NAS models with two or more ports offer a feature called link aggregation. When connected to an Ethernet switch that supports LACP (Link Aggregation Control Protocol), the NAS can balance the data between Ethernet ports to avoid a bottleneck. If multiple computers on the network access the NAS frequently, link aggregation can improve network performance among them. It does not, unfortunately, double the amount of data that gets fed to a single computer, so you won’t see a speed benefit in that case.

CPU

Since a NAS is a full-fledged computer, not just a dumb hard drive, it requires a processor to run the software and manage storage. For most uses, the type and brand of CPU don’t matter, as they can all serve files well. The CPU specifics become relevant when encrypting data or transcoding video to watch on devices that don’t support that resolution.

Memory

As with any computer, the more RAM a NAS contains, the more capacity it has to accomplish its tasks. You’re not running Photoshop on it, but more RAM helps when the unit is handling multiple simultaneous connections, encrypting data, and other duties. Look for a model that you can expand with more RAM. Even if you don’t max out the memory when you buy it, you can upgrade it later.

Power Consumption

A NAS is designed to run continuously, so check how much energy it requires both under normal operation and when drives are in low-power or hibernation mode. For example, the Synology DiskStation DS418play (the model I purchased) supposedly uses 29.01 W during access and 10.59 W when in its disk hibernation mode. For a current Mac mini, by contrast, Apple specs its power usage as 85 W for “maximum continuous power” and an idle usage of 6 W, so it’s likely that it would average higher than the DiskStation DS418play based on what the Mac is doing.

Hardware Encryption

If it’s essential that your data remain encrypted while stored on the NAS, look for a model that offers hardware encryption. You can still encrypt data without this feature, but doing so requires more CPU power and is slower than dedicated encryption hardware. Reading and writing encrypted data involves a decrease in performance overall, but some hardware assistance is preferable to none. Also, check whether the NAS you’re considering encrypts data at the volume level or just at the folder level.

Hardware Transcoding

If you’re planning to host your audio and video libraries on the NAS and stream the content to computers and devices on the network, consider buying a model that supports hardware transcoding. This feature more quickly converts high-resolution video files to versions that are optimized for the destinations. For example, let’s say you capture a 4K movie file using an iPhone X: when viewed on a 1080p HD television, the NAS streams a transcoded version suitable for that device, discarding the overhead of the 4K resolution data.

Plex, a popular software system for streaming media, uses only the CPU in a NAS for processing, so hardware transcoding isn’t relevant for Plex users. Prioritize the CPU and RAM specs when looking at possible Plex servers.

RAID/File System Support

A NAS that includes more than a single drive uses a RAID scheme to make the disks appear as a single volume. Check to see which RAID levels are supported, in case you want to change them manually. It may also employ its own custom RAID configuration. Synology, for instance, uses Synology Hybrid RAID (SHR), which offers striping and redundancy while maximizing the amount of usable storage. Drobo’s BeyondRAID technology works similarly.

Depending on the model you’re researching, you’ll run into two file systems: the long-standing ext4 and the newer Btrfs, which adds support for snapshots and some low-level data integrity checks.

Normally, a file system isn’t a feature most people need to worry about; I bring it up here because some vendors use Btrfs as a marketing point. Ext4 tends to be a bit faster than Btrfs and has a longer history. Btrfs was designed as a modern alternative that’s more active about preserving data. Think of ext4 as being roughly analogous to the Mac OS Extended (HFS+) file system and Btrfs as the APFS (Apple File System) file system introduced in macOS High Sierra (see “What APFS Does for You, and What You Can Do with APFS,” 23 July 2018). I wouldn’t call Btrfs an essential feature, but you’re likely to be faced with the decision.

Other Considerations

There are plenty of other things to note, such as the amount of noise the NAS makes and the operating temperature if its location is in a warm environment. I’m also tempted to add performance throughput to this list—after all, faster performance is better, right? However, manufacturers don’t provide it for all models, and those numbers come from controlled tests designed to come up with the best results. So, by all means, take performance into account, but with a skeptical eye.

Why You Should Buy NAS-specific Hard Drives

Hard drive docks make for an excellent general-purpose storage solution. They connect to your computer and accept standard internal hard drives for backups without being burdened by an external drive’s case, cabling, and power supply.

As a result of using such a dock over the years, I have stacks of old drives lying around that were retired when I moved to higher capacities. Wouldn’t it be great to throw them into a NAS and make use of that storage?

It’s a tempting approach, but don’t do it, for three reasons:

- Combining drives of mismatched capacities can leave you with unusable disk space in many RAID configurations.

- Those drives have already seen a lot of use, so the probability that one will fail is higher.

- Most important, drives designed for NAS include features for minimizing data corruption, sensing and minimizing vibration, adjusting rotation speeds to last longer, and better enduring the rigors of always running.

Although there are many drive manufacturers out there, my research consistently turned up good reviews of WD’s Red line and Seagate’s Ironwolf line. Both companies also offer “pro” versions that are further hardened for NAS use but are more suited for large enterprise installations.

A NAS Primer

A NAS can be a versatile addition to your Mac’s storage, but the number of options and specifications when buying one can be paralyzing. Use this article as a reference when doing your own research.

After you’ve added a NAS to your setup, see my book Take Control of Your Digital Storage to learn more about working with files on the NAS, accessing it when you’re away from the network, and more. The book also covers other aspects of digital storage, such as using Disk Utility and First Aid, understanding the APFS file system in macOS High Sierra, and strategies for freeing up disk space.

We’re running a three-question survey to see what TidBITS readers think of NAS devices.

Several years ago, I purchased a dual-bay QNAP NAS server for the purpose of storing all my media. In retrospect, I bought the cheapest model available and set it up with a simple RAID 0 configuration. It was grossly underpowered and it crashed constantly. Although it always rebooted itself, the Macs on my network lost connectivity every single time. I ended up donating the NAS enclosure, but keeping the WD Red drives and mounting them in drive enclosures. Actually, those two drives are still functioning as backup boot drives, some eight years later.

Since that time I have used a Mac Mini (replaced once) as a media server, first with synchronized external hard drives, then with a 4-bay thunderbolt external drive from OWC. I have a RAID 5 configuration which has been functioning perfectly for the past few years. However, the thunderbolt drive is noisy - way too noisy to use as a media server, so I had to build a ventilated, sound-isolating cabinet for it. Using a Mac Mini as a dedicated server is overkill, but it has some major advantages on an all-Mac network. All of the apps I have on my other Macs work on the Mini, and maintaining separate accounts for separate users is no more difficult than on my other Macs. I can use the same firewall configuration and the same anti-virus software, although with an additional license. With a little work and by hooking it up to my TV, it can be used as a streaming device too.

I think there are advantages and disadvantages to any file server configuration. My early experience definitely soured me on the use of a NAS. Although I see many advantages and although a NAS is a lot more affordable than a dedicated Mac with an external RAID array, there are a lot of drawbacks to be kept in mind. Perhaps the biggest one is that the file system of a NAS is not a Mac file system and setting up multiple user accounts is nothing like it is on a Mac. Both may use Unix file permissions, but the tools available on a NAS are much more rudimentary and fixing things is much more difficult and involved. If you’ve every tried setting up a router using the built-in web interface, particularly if you’ve had to configure limited MAC access and port forwarding, setting up a NAS is even more complicated. Network security is particularly important - an improperly configured NAS may allow hackers another way into your network.

I think anyone considering a NAS should ask themselves some key questions. Do your really need a NAS? Would a cloud-based service work for you? The monthly fees may be steep, but there’s virtually no work involved in setup, reliability is high and access is available from any device, anywhere in the world. Also, how much redundancy do you really need? A RAID 0 or RAID 5 configuration provides automatic data redundancy but at a cost. If the data on your server isn’t changing all that frequently, having two separate, synchronized external drives can be a lot more practical - you just have to make the effort to keep them synchronized using software such as ChronoSync. Also, Backblaze provides unlimited backup, and that includes attached external hard drives of any size, but not a NAS.

The bottom line in my opinion is that if you don’t need separate user accounts or a high degree of network security, then a NAS may well be the most cost-effective way to go. If you have multiple Macs on your network that are always connected, always on and are not overly taxed by CPU-intensive tasks, then there is little point - multiple external hard drives should be more than adequate. If your needs are more complex, however, and you need a lot of on-site storage with multiple user accounts or with a high degree of security, however, then you’re probably better off with a dedicated computer as a server and redundant external storage.

There are Thunderbolt 2 10GbE adapters as well as Thunderbolt 3 plus bare PCIe cards you can put in a Thunderbolt chassis. 10GbE is pricy but it is getting cheaper; the Sonnet Solo 10G Thunderbolt 3 is less than $200, almost half the price of the last Thunderbolt adapter I bought (to use it with a Thunderbolt 2 Mac, I think you can unscrew the back panel, disconnect the TB3 cable, and attach a TB2 to TB3 adapter, those adapters are bidirectional). I was looking at small, “cheap” 10GbE switches recently, they’re roughly $500: Netgear XS708Ev2, QNAP QSW-804-4C, Buffalo BS-MP20.

My understanding is LACP (Link Aggregation Control Protocol) requires configuring it not only on the NAS but also on the network switch ports it’s connected to, requiring it be a managed network switch (at work we definitely had to have the ports on the big Cisco switch configured for LACP for our NASes. NAS’s. Naxen?). Few people at home have a managed network switch and they would be another cost.

CPU and RAM are important for RAID5 performance and for actual file serving, not just for running “apps” on a NAS. If a NAS isn’t hitting the limit of gigabit Ethernet serving files, it’s probably because the CPU is underpowered.

It has become fairly common for NAS vendors to not only sell devices with a fixed set of bundled capabilities but also with optional “apps” one can install and they don’t necessarily have to be developed by the vendor. My impression is Synology has the most robust app ecosystem.

RAID 0 provides no internal redundancy, every file is split into chunks spread across each drive. The odds of losing the data stored on a RAID 0 array is multiplied by the number of drives it contains. Read/write speeds are faster for RAID 0 than a single drive but that’s rather pointless in a NAS because even a single magnetic drive is faster than gigabit Ethernet, the network should be the bottleneck.

Thanks for your comments, and I apologize for an early morning slip - I meant to say RAID 1 and not 0.

There’s no doubt that a NAS is a tempting approach to providing for massive storage for shared data on a network. A preconfigured NAS is definitely the way to go, and with the availability of apps, the NAS can serve as a very effective media server without the need for a dedicated Mac. With PLEX or Kodi installed, your entire media library can be accessed from any DLNA-capable device on your network. If you’re expecting to back up personal data to a NAS, however, or to have multiple accounts, you’ll need to invest a bit more time and effort. Also, if you want to use it to store your iTunes and Photos libraries, keep in mind that although the content can be shared, they can only be managed by only one computer at a time.

Although a NAS is cheaper than having a dedicated Mac, it’s still a four-figure expenditure. It’s not worth it to try to get by on the cheap with an under-powered CPU. Also, redundancy is no substitute for a proper backup. A RAID5 array protects against a single drive failure, but it doesn’t protect against a natural disaster or accidental file deletion. Backblaze provides unlimited backup for attached hard drives, but not for a NAS. For that, you need a B2 account and Backblaze charges by the GB - for storage, uploads and downloads. The 6TB I have in my Thunderbolt drive, currently backed up for free as part of my Backblaze package, would cost an additional $400 annually if stored in a NAS. Over the life of the drive, a dedicated Mac mini would be cheaper.

Yep, I agree with pretty much all of that. Note that Backblaze B2, like basically all cloud storage providers, does not charge for data uploads, only storage, downloads, and a small amount for API calls.

BTW, Wasabi is another cloud storage company, they charge slightly less per GB/month than B2 and they don’t charge for uploads, downloads, or API calls.

My needs are somewhat less industrial. When I bought my 27" iMac more than four years ago, all the Thunderbolt solutions were expensive RAIDs. Then OWC came out with the original Thunderbay 4 drive enclosure and my problems were solved. I had a variety of hard drives, two from external cases and two from my old Mac Pro. But a RAID requires matched drives, and mine were various. The Thunderbay 4 supported those mismatched drives just fine. They mount individually on my desktop. Of course I’ve upgraded all the drives in the meantime, but the Thunderbay 4 matches my iMac with the original Thunderbolt 1 standard, which is plenty fast enough for 7200 rpm drives.

I store most of my data on one drive and back it up on another. I also have a Time Machine partition and a clone of my internal drive, and one other drive for various archives. Oh, and I have a bare 5TB drive that I’ve partitioned for additional backup that I started keeping in a safe deposit box a few years ago. I use a Voyager S3 “toaster” to access this and other bare drives.

If you have a newer Mac with TB2 or TB3, OWC has kept up with the times, offering compatible versions of the Thunderbay 4. And, unlike some reports I’ve heard, my Thunderbay 4 is not noisy. I suspect the noise issue has to do with the drives one is using rather than any inherent problem with the enclosure. Oh, and OWC makes models designed for 2.5" drives and SSDs as well.

I have a small local LAN using a simple Ethernet switch over which I can share any of these drives to computers connected either by wire or via WiFi. Screen Sharing also works reasonably well. And my Router uses the switch to provide internet access to all connected computers.

In any case, if you have lots of external drives cluttering up your workspace, a Thunderbay 4 is a good way to consolidate your drives and save space without the complexity of a RAID or a NAS. And it is easily upgraded as well, or rather the drives are.

This may be a bit off topic, but if you are considering a NAS, I think alternatives are relevant. Just as RAID and cloud storage are.

Old topic but maybe it’s still being monitored. Does the NAS have to be plugged directly into a free ethernet port on the router as most online tutorials show or can it be run through a multi-port ethernet switch (Gigabit or faster)?

Either will work fine. Most of the tutorials talk about plugging to the router as few homes have ethernet switches…

Cheers,

Dave

What this article failed to make clear is that RAID is not just used by NAS’s but can also be used by DAS’s too. So you don’t need a NAS to get a big multi-drive volume; you can just as well get a RAID box that’s a DAS.

What is more interesting and open for debate about the differences, is whether it’s better just to use an always on (low energy usage with M-series) Mac which has decent CPU/GPU with large DAS hanging off it via fast 40Gb Thunderbolt 3/4 (even if you don’t saturate the max 40Gb speed), vs. just having a decent 10GbE NAS somewhere on your network?

That question is typically completely avoided in NAS journalistic articles, for some reason.

AFAIUI, most modern Macs will beat almost any NAS for reliability and certainly performance (maybe except for only the most expensive NAS’s CPU’s perhaps??), making the Mac+RAID DAS idea both faster for moving data on/off the storage box but also for transcoding duties (using the Mac to do it), and affordable Backblaze-type data backups.

I wish there were better options in the DAS box world.

My three old Drobo multi-drive boxes were retired this last week. The 5 drive (5D) Thunderbolt 2 power supply had died, the 5N2 NAS was off loaded and the original 8 drive NAS was too slow today and only 18TB of storage. Of course the other main issue is the DROBO drivers will likely die in the next Mac OS upgrade. I replaced them with a Synology 1522+ NAS that has five 12TB drives and all the other Synology options are maxed out so it also has 10Gb ethernet. It has a hot swappable drive capability like the Drobo drives had.

Both my Mac Studio Ultra (10Gb ethernet 128GB Ram and 8TB SSD) and my 2019 Intel i9 Mac mini (10Gb ethernet, 64GB OWC Ram and 2TB SSD) are connected via an 8 port 10Gb switch to the DS1522+.

The Mini has a 4 bay OWC USB C enclosure with four 8TB drives inside attached as a SoftRaid 5 drive. We updated to the new Netgear ORBI 6E wifi system so we ran a 2.5Gb line from it’s router to the 10Gb ethernet switch.

We use Apple’s iCloud to back up all of the iDevices (iPhones. iWatches, big and small iPads). We have six laptops with years of photos that are being moved to the two disk arrays. Takes lots of time even with 10Gb ethernet as the drives through put is the throttle to the process.

NAS is slow but the OWC drive is speed limited as well by the hard drives data transfer speed.

Finally getting backups working like I wanted to do years ago and this is a much more user friendly system for me at age 78.

Carbon Copy Cloner does the backups for me.

Just keep in mind 40 Gbps is the theoretical peak on paper. For data transfer, there’s actually only 32 Gbps left. And for real-world storage i/o that translates to about max 28 Gbps read and 21 Gbps write. While that’s still a factor >2 over 10GbE, it’s also about a factor 2 lower than the frequently tossed around “40 Gbps”.

And obviously, that’s total b/w so if you dangle anything else off that TB port (eg. external display) that will further reduce. If you’re out to get max throughout to DAS, probably raiding across multiple separate TB-attached NVMe flashes (which each have to be on their own TB bus, not just port) would be the way to go.

For those who are moderately technical, it’s straightforward to build your own NAS with much greater CPU power (say for Dockers and VMs). unRAID and TrueNAS both work well and have great community support, and support multiple levels of redundancy, so you can withstand more than 1 disk loss if you have a hardware failure.

These are definitely not quite plug-and-play like commercial solutions are supposed to be, but I wouldn’t say they are tremendously difficult, either. I do think they are worth considering if you’re interested in either NAS or DAS.

Kevin

I was really talking about ‘your average user’ who doesn’t want to build their own custom-build stuff at all anymore, but just buy off-the-shelf stuff, plug-in and use – much like a typical Mac user who wants to get stuff done, rather than having to manage technical stuff in order to do so.

The trouble I’ve noticed is the myriads of NAS raid boxes that are offered in many models from many companies, whereas there just aren’t many Thunderbolt DAS raid boxes of any type in comparison.

For HDD’s, the OWC Thunderbay’s seems to be the only multi-bay ones that are reasonably affordable, that you can buy your own drives for to save money. But the fans OWC use are truly atrocious so you get a lot of fan noise (on top of the HDD noise inside)! And as they use software raid, there have been reliability issues with using their SoftRaid for people who need more than R0 or R1 that Apple’s Raid offers, especially using 4+ bay boxes where R5/R6 is more typical.

The only other options for are hardware raid Thunderbolt boxes: LaCie (Seagate’s brand), SanDisk/G-Tech (WD’s brand), and Pegasus – all of which are pre-populated with HDDs, and typically the >2-drive models cost a lot of money per-TByte accordingly.

For SSDs, NVMe’s are the ones to aim for as they offer greater speeds yet are starting to cost similar money to larger volume but much slower SATA SSDs. There are no decent quality empty enclosure Thunderbolt 3/4 multidrive (>2) NVMe raid boxes all all (in order to achieve a single large raid volume, rather than extra speed).

Again, the only ones seen are two 4-bay’s from OWC: Express 4M2 (super-loud fans!) and Thunderblade (only comes with drives and expensive – though some users on MacRumors have resorted to emptying a lower-volume Thunderblade, adding 4 x 8TB NVMe sticks, and re-adding thermal paste as it’s passively cooled – in order to get a QUIET+LARGE VOLUME of decent enough speed NVMe solution! Not exactly off-the-shelf though, is it!)

So not much out there right now.

…Jellyfin 100GbE for a $gazillion, anyone?

N=1 case but we’ve been using RAID 5 on Thunderbays with Softraid for over a decade without a single RAID issue. They’ve been solid as a rock. Naturally in that time we’ve had a few disk failures but we swap the disk out, it rebuilds and don’t have so much as a hiccup.

Our Synology cluster has been pretty good but we’ve had one instance where it corrupted itself so badly we completely lost one side of the cluster.

Yup, need more DAS options, but ultimately the problem is macOS: no RAID 6, so even if you could economise on drive and enclosure and avoid proprietary hardware RAID crap (Mac audience, all in-band managed, with bloatware to match) you can’t have the reliability of even a custom-built NAS box. So either pay through the nose for the moderate capacity or else do what I did, settle for bus-powered NVME enclosures and use application-level redundancy (read: Time Machine, Arq). Even running Linux on the old Mac Minis isn’t an option because external DAS boxes really are confined to the same Mac-centric audience. Ultimately lots of people will (correctly but sadly) conclude that just buying a NAS is simply the better option, even though it’s clearly inferior from both a performance and flexibility standpoint than running your NAS on a Mac with external storage. But there we are.

For affordable products targeting the desktop/consumer space, you mean.

In the enterprise/server space, you can get servers with U.2 and U.3 slots. These drives physically resemble 2.5" SATA drives, but they carry PCIe data on the connectors, making them functionally equivalent to NVMe.

But these drives are expensive, and I’ve only seen the connector used on rack-mount server chassis. So they’re really only going to be practical if you want to spend tens of thousands of dollars on an enterprise or data center class storage server.

Yep consumer/prosumer space. Clearly those U.2/U.3 things are more for serious –typically business– users with the cash to match.

Anyway, I wonder if we’ll finally see some more 4-drive NVMe box options over the next few months? Otherwise I’m likely to wait a bit longer then go the OWC Thunderblade manual upgrade route previously mentioned above. I need a quiet(!), fairly large volume box for my media storage.

Also perhaps 8TB-sized NVMe’s will have lowered a bit further to make them feasible in whatever box I end-up using (in 8TB size, “Corsair MP600 Pro NH” are the most affordable right now, AFAICT, and they’re decent TLC – rather than QLC, which to my understanding, heavily slow-down after they fill their cache).