Is Your Future Distributed? Welcome to the Fediverse!

A new concept with old roots has started to come to the fore on the Internet: federation. Instead of a centralized system, typically run as the equivalent of a single giant database by a company with a profit motive or investors to repay, federation relies on distributed servers. Each server, called an instance, runs a common protocol. Servers using that protocol agree to exchange nuggets of information, like brief posts or pieces of media. The best-known and most popular example of a modern federated system is Mastodon, a micro-blogging network that has garnered great attention as the primary alternative to Twitter. (See this article’s sibling, “Mastodon: A New Hope for Social Networking,” 27 January 2023, for more about the ins and outs of what Mastodon is, why you might join, and how to use it.)

The concept of federation has garnered recent attention because of the rise of the Fediverse, a set of open-source protocols that manage user activity on a server and the interchange of information among users on other, independently operated servers. (The most widely used such protocol is ActivityPub, supported by the World Wide Web Consortium, but there are others.) Server software—typically open-source as well—supports federation by allowing users to register accounts locally, then letting local users follow and be followed by users on both the local server and other servers within the Fediverse that run the same protocol. In essence, this open-source system builds a skein of connections across servers that don’t have to make prior arrangements to interact.

There’s no center of the Fediverse. Each participant and each server has their own agenda, operating principles, and local data store. The connections among servers are all consensual, voluntary, and subject to change. No authority dictates whether a given server can or can’t connect to another; nor can an overarching authority demand that users or content be removed. (Governments and courts are another matter, but they are always extrinsic actors with regard to individual or commercial speech.)

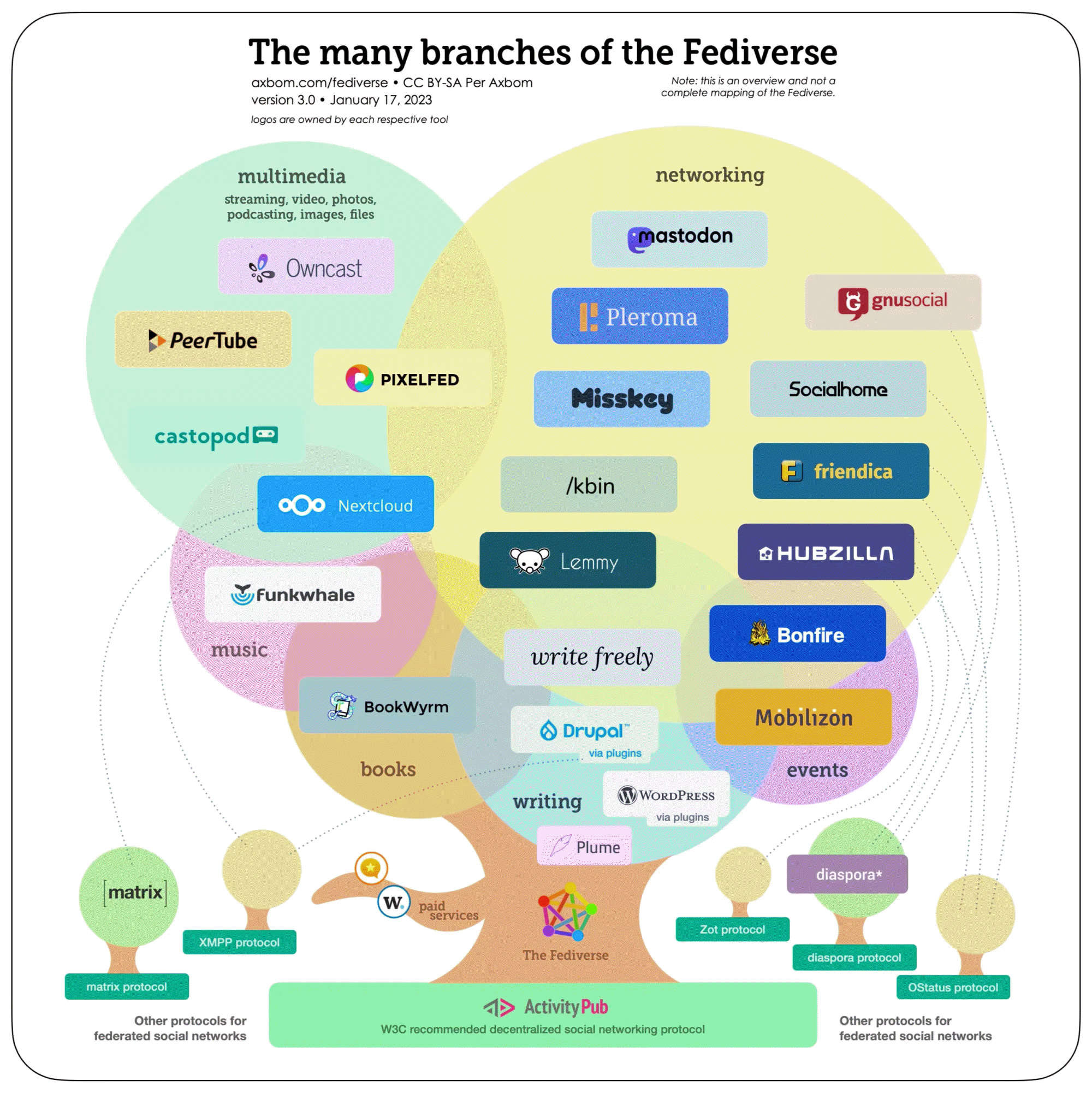

You can find Fediverse software for exchanging music, social networking, and photo and music sharing, among many other purposes. This nifty site—non-authoritative by its nature!—explains the Fediverse in depth and lists a huge array of Fediverse apps. I also love this graphic created last November by Per Axbom that visualizes many Fediverse apps as branches and leaves of a tree.

The Fediverse exists in stark contrast to most organizations’ centralized, commercial efforts to connect people via the Internet. It’s an example of the ethos of IndieWeb, which simultaneously looks back to the best of the Internet’s earlier days and forward to the best of what can be built today. The Fediverse is designed to share resources in a cooperative way that lifts all boats while also providing individual points of authority that decide how to connect to other independently operated networks and servers.

While your immediate interest may primarily be Mastodon—and for that, see the article linked above—the Fediverse is broader, a galaxy in which Mastodon is the language of peace among many star systems and trade routes, while co-existing with many other federated systems. Let’s dig into what the Fediverse is and what it means.

Back to the Future of Non-Centralized Interactions

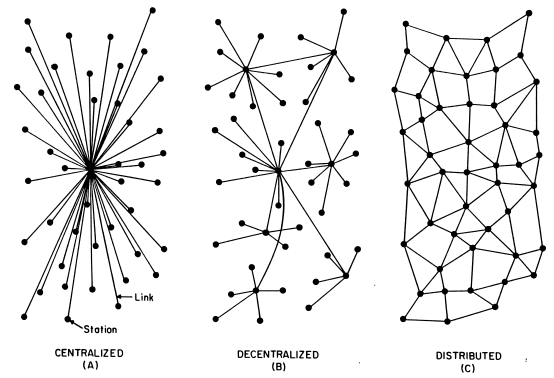

In the universe of possibilities of how people communicate electronically with one another, the choices largely separate out into centralized, decentralized, and distributed. This is not a new distinction, as you can see in this network types diagram from an influential 1964 research paper by Paul Baran.

Here are the definitions with services as examples:

- Centralized: Twitter is centralized. One company owns the protocol, data, and servers. It manages the accounts, sets policies, and has total control over advertising, what’s posted, who uses the service, and how third parties can access the data. (To wit: Twitter’s abrupt banning of third-party app access to the company’s API with no notification—see “Twitter Bans Third-Party Client Apps,” 20 January 2023.) The center is the truth: the only place to interact with the abstract notion of what the service is.

- Decentralized: DNS is decentralized. There is a hierarchy for the domain name system, which defines how parts of the Internet can be discretely named and associated with network IDs and other data. Certain resources in the domain name system are operated by central authorities who set some policies and operate many critical technical resources and servers. These authorities hold certain truths, like which servers hold the lists of .com and .org domains. Despite all that, within fairly loose constraints, anyone can host or delegate hosting of a domain name that they own, choosing all the associated values like subdomains, mail servers, site validation text entries, and so on.

- Distributed: The Fediverse is distributed. Each Fediverse instance is its own Little Prince world that can choose to engage with other servers through federation, the interchange of information stored locally with other servers remotely. There’s no one in charge and no single place to go for definitive truth about the network.

The oldest among us might find this reminiscent of what used to be called store-and-forward systems, like the original FidoNet, UUCPNET, and BITNET. These were early examples of a kind of federation. Every server knew how to pass information destined for non-local accounts, even if that merely meant passing it along to the next server. With UUCP, for instance, mail could be addressed using bang routing, which listed out each server between the source and the destination. These networks were critical in the early days of internetworking when modems were expensive, bandwidth scarce, and no backbone existed.

Centralization is, by definition, in opposition to that spirit. It spread partly because of the cost of resources required to manage the necessary computational and bandwidth requirements as the Internet grew richer in media and more complicated. The technical bar to entry also deterred mass adoption. Newer services provided an easier on-ramp to some components of the Internet, and social networks captured audiences who primarily used email and a browser, and didn’t want to blog, build a Web site, or post on Usenet.

Something that charts a new course on old paths has to demonstrate a thriving community, provide easy access, and work reliably. It’s hard to argue that all three of those exist today in the Fediverse, but each of those elements is heading in the right direction.

Mastodon and the Fediverse represent something far better than Web 2.0—and vastly better than what’s already seen as the ill-fated, ridiculously branded metaverse/crypto-focused Web3. The Fediverse is more like Web 1++: what you liked back in the early days, only modern and much more of it.

The Limits of Federation

Federation has some drawbacks related in part to the lack of a central organization that handles infrastructure and policy. That said, these drawbacks are really all two-edged swords, with both negative and positive aspects:

- Instances choose which other instances to federate with. There’s no way to force an instance to exchange messages with every other instance. An instance you’re on may block lots of others for trivial reasons. Generally, that’s not the case because capriciously run instances wind up only with users who strongly agree with those capricious decisions (which sounds a lot like Twitter these days).

- Instances that are media-heavy, user-heavy, or interaction-heavy may have higher server and bandwidth costs than less-loaded instances—perhaps thousands of dollars per month instead of just a few dollars a month for a smaller instance.

- The admins who run an instance have a burden of moderation to ensure users on their instance are happy and that the instance isn’t engaged in activities that violate the law. In the US, instances also have to be responsive to Section 230 requests, legally binding demands to remove reported content immediately.

- Most instances are run by an individual or small group volunteering their time and donating their money. Few involve paid staffers. Thus, every minute an admin or moderator spends dealing with something structurally, socially, or legally wrong is time stolen from something else they could be doing.

- ActivityPub, the underlying protocol, wasn’t designed to be efficient in the face of massive interconnections among servers. This can lead to long delays in message propagation. However, because ActivityPub is open source, developers are actively working to improve efficiency.

You might recognize some of these problems from email, which is effectively a federated service despite the massive numbers of consumer and business email accounts hosted by Apple, Google, and Microsoft, as well as for employees by large corporations. For instance, the admins who run email servers can and do block mail from going to or being received from other email servers; constantly updated lists of bad actors aid that process. Individual email recipients can use tools to block messages from individuals or entire domains. (In contrast, admins of federated servers may have to examine individual messages constantly, something that’s rarely done with email). Email used to suffer from limitations on email attachment size and volume of messages sent, sometimes resulting in huge backlogs in receiving email. These issues have subsided over time as the costs of bandwidth and running servers have dropped.

Despite these problems, email has thrived. Turn-of-the-century predictions that email would become increasingly balkanized, with servers interacting only with subsets of other servers, didn’t come to pass. One specific worry was that any given email message might not be able to get from here to there, wherever there was, because of a block in between. That hasn’t happened. The success of email as a decades-long experiment in federation should give us hope.

In the Fediverse, most instances do block other instances. But it’s typically a subset of other instances for various bright-line reasons. The most common are instances used by people with extremist ideologies. This so-called defederation—blocking traffic from another instance—happens at the discretion of the admins of an instance. Within Mastodon, in particular, you can also mute or block accounts or entire instances aside from the instance on which your Mastodon account is hosted. You then will never see that individual or posts from that instance.

Admins can also take various moderation actions against individuals and posts or other items. In the Mastodon world, some instances have a robust moderation team and a detailed acceptable use policy. Some even have a review board or advisory group to ensure fairness and offer recourse. Moderation doesn’t benefit from scaling, making it a challenge as the Fediverse grows. An increase in users and activities could result in the heavy-handed removal of posts and people or insufficient throttling of bad actors. That, in turn, could lead to other instances being defederated from an instance that is either too severe or not severe enough!

Fortunately, while every account must live on a particular instance, you own your social graph, your connections with other people. You can migrate your identity from one server to another, bringing followers and those you follow along, and leaving behind an automated forwarding address. (With Mastodon, your posts don’t migrate but remain in amber on the previous server unless an admin there removes the account.) If you’re blocked or banned on the instance where the account you want to migrate lives, that naturally introduces complexity.

If a given Fediverse project, including the underlying ActivityPub protocol, became too radical in its behavior, it could be forked, or become a duplicate of the project taken in a new direction, because most of these efforts are open source. People running instances that use a protocol could opt to install the forked version if they didn’t like the primary direction. This could split up the Fediverse or a service within it, but in practice, most forks don’t deviate far from the primary branch.

Not all apps compatible with the Fediverse are dedicated to it. For instance, Manton Reese’s Micro.blog service supports ActivityPub as a format and enables it by default on accounts created starting in October 2022. In Mastodon, you can add a Micro.blog user’s feed as easily as adding another Mastodon user. WordPress users can install an ActivityPub plug-in (in beta) to allow similar feed subscriptions. The Fediverse is also highly flexible around RSS, using it as a sort of lingua franca to obtain non-interactive feeds.

Is the Future One in Which Divided, We’re United?

The future of the Fediverse isn’t dependent on mass adoption by hundreds of millions of people. No company has to pay thousands of employees or maintain massive server resources. Instead, it’s predicated more on momentum and commitment. Open-source projects and volunteer-run servers require people who believe what they’re doing is worthwhile, whether from enlightened self-interest or generosity.

The excitement over the Fediverse is that we could see the blossoming of a dream held in the equivalent of an Internet seed vault for nearly two decades, thanks to the current focus on Mastodon. As blogs died, RSS receded, and people owned less of what they posted and their relationships with others, the question was whether the seeds of the dream of a distributed Internet would die ungerminated. The Fediverse is fresh soil. Let’s see what blooms.

While on the subject of federated social networks, does anyone know of a federated equivalent to Facebook?

Mastodon (and most of the non-federated free-speech social networks) seem to be following the Twitter model - posting short messages to be seen by subscribers. Sort of a wide-area version of iMessage.

But Facebook (at least the Facebook of 10 years ago, when I was using it and when it was still fun) is different. It also allows sharing of long-form content (like blog posts), photo sharing (albums your friends can view), other kinds of shared data (e.g. leaderboards for connected games and (in the old days) the ability to personalize a home page for your friends to see, with more than just a picture and a name.

I’ve been out of the social network loop for a long time, for reasons well beyond the scope of this message, so I don’t know if anybody has created a system with features like the FB of old. If there is such a system, I’d love to know about it.

I’m very interested in responses to your query too. I’ve lived a pretty happy and fulfilled life without paying any attention to Twitter, so Mastadon - while appealing in some ways - doesn’t hold a lot of interest. But I have maintained a Facebook presence, largely to keep track of far-flung acquaintances, and to some degree the activities of musician friends. With virtually nobody maintaining personal email mailing lists anymore, Facebook has become my primary way of finding out about local musical performances and events.

But these days my FB feed seems to be 90% advertising and “selected for you” junk, and I’ve been teetering on the edge of closing that account, were it not for the fact that about once a month I find out about a concert or a talk or some public activity of interest that I wouldn’t have heard about otherwise. I’d love to find a new channel for this information that lets me filter out most of the garbage.

I’ve never used it but I think Facebook is what Friendica is modeled after. Another is diaspora* but l think it is more distinct.

I haven’t seen any platforms following Facebook’s model of two-way Friending, If I accept your Friend request, we both can access whatever each other shares with Friends. Newer platforms are one-way, I Follow you but you may choose to not Follow me. By default, Mastodon accounts have “open” Follows (like Twitter), anyone can immediately Follow you, you get a notification they have done so; if you have a problem with them, at any time you can remove them as a Follower and Block them from seeing what you post. But you can also set your account to require Follow requests, people ask to Follow you and you can accept them or not. Posts can be set to be visible to Followers-only by default or on a post-by-post basis (but like Direct Messages, don’t think of them as truly private, they can also be read by any instance administrator with at least one intended recipient). I assume these Mastodon features are shared by many other systems using ActivityPub.

@phfweb @cwilcox

I would suggest micro.blog. Manton added support for Activity.Pub a few months back and has been improving it. What’s great about micro.blog is that it has support for both short or long posts as well as photos. That’s for the basic $5/month plan. $10/month also adds support for video and creating podcasts.

micro.blog is great in that you have your blog which can be at your domain name or just at your username, mine is Denny.micro.blog. Posts can be any length at all. Blog themes are based on Hugo and you can pick from community created themes or create your own. In addition to the standard blog your posts also appear on the micro.blog timeline for anyone that follows you. So it has a social/timeline aspect for those that want that. And of course, comments are built in. In addition to following micro.blog accounts in your timeline, there’s also support for following other websites and mastodon accounts on that timeline too, almost like a built in RSS reader.

It works very well from the website or you can use apps that are available for Mac, iOS, and Android.

There’s also a family/team plan if you want to use it for a small group of shared posts.

Re: Mastodon

I like the fact that there is a lot of variety in the servers, depending on who is controlling them. Some will be like the wild west but others will be tightly controlled and more friendly. It is early days but I think we will see some good enhancements down the road.

I am not a fan of social media companies that make money by amplifying conflict to get eyeballs for ads.

I want to like micro.blog and recently signed up for a paid plan to give myself some options to experiment but can’t figure out what it is useful for vs. Mastodon. I’d love thoughts from folks here.