Reacting to Unsolicited Two-Factor Authentication Codes

I have long encouraged the use of two-factor authentication (2FA) or two-step verification (2SV) with online accounts whenever possible (for more about the difference, see “Two-Factor Authentication, Two-Step Verification, and 1Password,” 10 July 2023). Either one is a huge security win because, after entering your password, you must enter an authentication code to complete the login.

I standardized as many of my authentication tokens in 1Password as possible because it enters them automatically for me (see “LastPass Publishes More Details about Its Data Breaches,” 3 March 2023), but many online services continue to rely on SMS text messages due to their ease of use, even though authentication apps are more secure than SMS. Don’t let a site’s reliance on SMS dissuade you from turning on two-factor authentication—2FA via SMS is still far more secure than not using 2FA.

The most common problem with SMS is an attack called SIM swapping. An attacker poses as the victim and convinces the carrier to port a phone number to a new device, effectively taking over the victim’s communications. It requires knowing the victim’s username and phone number, as well as additional identifying information like the last four digits of a Social Security Number. Unfortunately, information like that regularly shows up in corporate data breaches, such as the recent Ticketmaster breach of personal data and financial details from 560 million users.

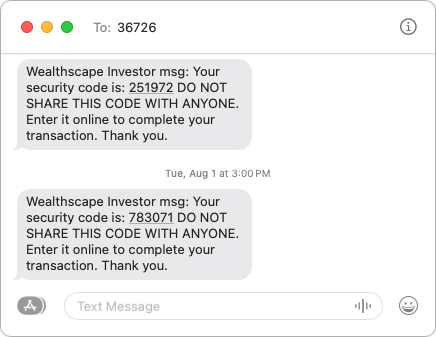

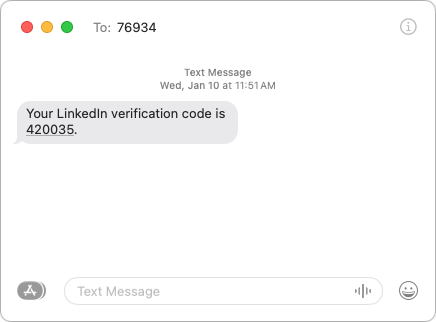

More commonly, you may receive an SMS text message containing a 2FA code you didn’t request. This one caused me a brief moment of concern earlier this year, and a friend asked me about one they received more recently.

What should you do if you get an unsolicited 2FA code? In order:

- Don’t panic. Receiving the code indicates that someone is trying to access your account and has your password, but the additional authentication step has prevented your account from being compromised.

- Never share an authentication code with anyone! A hacker may try to access your account, be blocked by two-factor authentication, and then email, text, or even call you with a trumped-up request for the code. Since authentication codes have a short lifespan, any such contact will typically happen right away. Many companies include advice against sharing along with their codes.

- Change your password without clicking a link in the message. Navigate manually to the account’s website, sign in, and change your password. Make sure the new password is strong, unique, and stored in your password manager. If the account in question relied on an old password that you also used for other accounts, which was common practice long ago, change the passwords on those accounts as well.

What does it mean if you receive an unsolicited 2FA code via SMS? Here are the main possibilities:

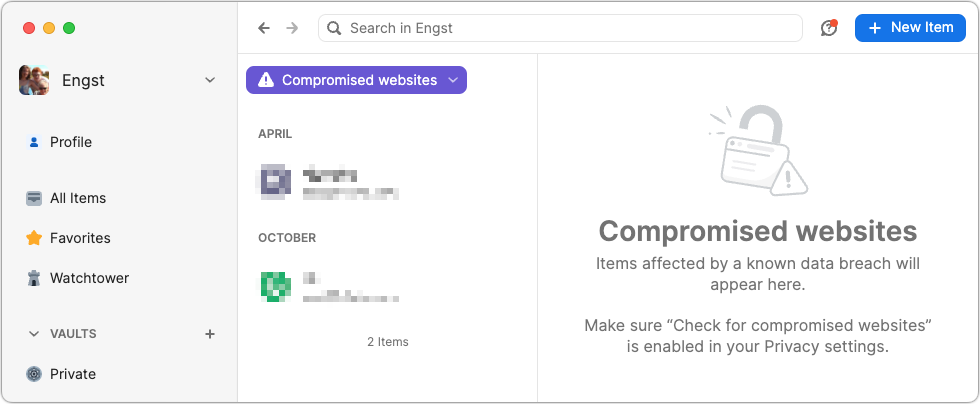

- Stolen credentials: The most common and worst-case scenario is that your email address and password were stolen, likely in a data breach, and the attacker is testing to see if they can get in. The Have I Been Pwned site is worth checking to see how many breaches you’ve been caught up in, but features like 1Password’s Watchtower are more helpful for identifying particular sites whose passwords should be changed. Other password managers have similar features. Always change passwords on breached sites.

- Identity theft: I’m having trouble working out all the steps here—I’m not a cybercriminal!—but it feels like there’s an identity theft attack vector that could result in you receiving unsolicited 2FA codes. I can imagine circumstances where an attacker had compromised your email and wanted to set up a new account impersonating you, but couldn’t finish the process without entering a 2FA code sent to your phone. Far-fetched, I know, but sophisticated attacks often sound that way. I don’t recommend automatically changing your email account’s password in response to receiving an unsolicited 2FA code, but consider it a warning to be alert for additional indications of having been hacked.

- Accidental or random triggering: If you have a common email address or phone number, someone could have accidentally entered your address or number instead of theirs while trying to create an account. It’s easy to type [email protected] instead of [email protected] or mistake the upstate New York 607 area code for the Boston 617 area code (a college friend at Cornell who grew up near Boston was once able to explain a wrong number call she received from someone attempting to call MIT, which used the same exchange as Cornell at the time). If you don’t have an account at the site in question and receive only a single authentication code, you can probably ignore it. But again, stay alert for other issues.

- Glitches: There’s no way to know if human or computer error was responsible for a 2FA code being sent out incorrectly, but stuff happens.

Regardless of the cause, if you ever receive an unsolicited 2FA code for a site where you have an account, change the password immediately. It’s easy to do, particularly if you use a password manager, and the extra peace of mind is worth the effort.

@ace offers excellent advice here.

His article once again reminded me of this issue:

It boggles my mind that not all carriers — at least as an option — offer a possibility to completely lock this down. It’s not like I port my number all the time so why does this have to be made so quick and easy? If lazy people want this to be easy and are willing to take the risk, fine, but I don’t. I’d love an option to say that until I show up in their store (or at their contracted service provider) with at least one piece of government photo ID in hand willing to sign and leave prints etc. my number will NOT be ported. Ever. And certainly not over the phone using bogus “security questions” that are comprised of public knowledge elements.

I thought T-mobile was pretty good at this with their porting protection option (forget the name they use for it), until I recently called to have it lifted when I left them. There was no additional check at all. No password entry, no questions, no nothing. There wasn’t even a challenge text — I guess perhaps because they assume if it’s my cell phone no. that’s calling, it must be me. The only saving grace was the port PIN. That was set and revealed on my user account with its separate authentication. No idea if I would have also been able to just get that over the phone too.

A few relevant comments:

I’ve seen a few sites that no longer ask for passwords. You provide your user ID, and the site immediately sends a code to you by SMS or e-mail (I guess that’s now 1FA). If you respond (click the link or enter the code), you’re logged in. You can click a link on the login page to request a password-entry screen, but usually not until after the code is sent.

On a site like this, getting a code means nothing - it means someone entered your user name or e-mail address (which might be a typo, depending on what it is), but nobody has your password.

I personally don’t like this system at all, but I’ve seen it on several sites these days, including Expedia and Home Depot. I don’t like it, but it seems that this is becoming popular these days.

Personally, I think web sites should do this:

It does mean that you may see more 2FA requests if someone’s trying to hack your account, but they won’t mean anything.

WRT SIM swapping, you’d like to think that the carriers have learned their lesson, but apparently not.

FWIW, when I (and my daughter) legitimately needed our SIM cards swapped (about a year or so ago) due to card failure, we went in person to a Verizon company store. They asked to see a photo ID. And for my daughter, they wanted mine as well, since I’m the person paying the bills on the family plan.

Just to add that I have a PIN set on my Verizon account and they asked for that as well as the government ID.

Another explanation for unsolicited two-factor authentication codes: you’re using an aggregator service to pull together accounts. For example: Fidelity Full View, Mint, Yodlee, Personal Capital (now Empower), or even Quicken.

The way these work is you give them the userid and password used for online access to your account. In some cases (like Citi Card) the financial institution has a special API for such access, but in others they’re effectively “screen scraping” the accounts web page.

The aggregator doesn’t actually save the password. They just pass it through to the site, and save the authentication cookie provided – the same as when you use Safari and choose an option to stay logged in.

But some sites won’t provide such cookies, or they don’t last very long. Then when the aggregator tries to access the site, it triggers an authentication request – but there’s no way for you to respond to it.

So when my bank sends me an unsolicited authentication code, I know I’m not being hacked. It is just that my bank is user hostile.

For me, this has always been the reason for surprising 2FA codes being sent. I think this should be mentioned in the main article (which is nonetheless very helpful).

I think a lot of SIM swapping attacks are carried out with the help of corrupt or compromised retail store and call center employees. So while taking as many precautions, such as setting up PINs and 2FA, as possible is important, there isn’t much end users can do to defend themselves from “inside job” SIM swaps.

Interesting! We have several financial sites that rely on Yodlee for access to our bank accounts, and while we’ve had plenty of problems with keeping those logins working, I don’t think I’ve ever gotten an unsolicited 2FA code from them. They certainly require 2FA codes when you first link the accounts, so I wonder how they get around that on a regular basis?

If Yodlee needed a 2FA code every time they connected to our bank accounts, we’d be getting unsolicited codes daily.

Dang, I’ve gotten a few but just junked them. Will have to await more attempts and then go to those and change the password.

I found pawned and the 1Password option has its own issues like saying I have a lot of duplicates, but I do not or, the password is too weak but, I cannot make it better because the site limits me to a low character password, etc.

But the thing I AM MUCH MORE WORRIED ABOUT is this “My voice is my identity” system that all the major brokerage firms and maybe some major banks use as the two factor for calling in about an account like a 401k or brokerage. With AI voice cloning nearly perfect, this is a problem.

This makes Full View, Empower and other aggregators kind a pain to use sometimes.

But sometimes, this will not work on a less secure, pension/state, or smaller financial web site. They are just not as up to date. So you manually updated the data every few months. In an odd way, that less secure one may be more secure because of them being less security tech hip.

That’s why it frustrates me when text messaging is the only 2fa method offered. I recently had my medical insurance provider “turn off” my authenticator app 2fa because they no longer support it and revert back to text messaging.

It really frustrates me when a business (I’m looking at you, Chase) decides to stop using email “because it isn’t secure” and instead requires SMS for 2FA.