TidBITS#1013/08-Feb-2010

The iPad remains in our thoughts this week, with Glenn Fleishman examining in detail the question of whether or not the iPad will kill Amazon’s Kindle and looking back at his 3G data usage patterns to see if the 250 MB iPad data plan will be sufficient. Jeff Carlson also contributes a video of Glenn building and showing a presentation in the iPad’s Keynote app. Plus, Steve McCabe returns with the story of solving a maddening color display problem that afflicted only some of his Macs, and we announce the release of “Take Control of Screen Sharing in Snow Leopard” and an update to “Take Control of Back to My Mac.” Notable software releases this week include FontExplorer X Pro 2.5, Espresso 1.1.1, iPhone OS 3.1.3, iTunes 9.0.3, and 27-inch iMac Display Firmware Update 1.0.

Keynote Editing in Action on the iPad

At Apple’s media event introducing the iPad (see Hands-on Impressions of the iPad, 29 January 2010), Glenn Fleishman and I wanted to know what the experience of creating a Keynote presentation would be like. Inspired by a blog post from Fraser Speirs (“iPad Fallacy #1: ‘It’s not for content creation’“), I created a short video of Glenn manipulating objects (resizing, repositioning, rotating) and activating the annotation controls (including a laser pointer) in Keynote’s presentation mode. (A high-definition version is available at the

video’s page on YouTube.)

New Ebooks Aid Remote Support, Collaboration, and Administration

Do you use screen sharing? We do, all the time. As an editor, I use screen sharing to collaborate with my authors, since it’s convenient to discuss the same document in real time, even if the people having the discussion are on different continents. It’s also a great teaching and tech support tool that lets me control an author’s Mac and show what I’m doing while I explain some odd behavior in Microsoft Word.

But the king of remote control is Glenn Fleishman, who uses screen sharing for these and many other tasks, including remote server administration. Glenn’s enthusiasm for the topic has caused him to check out all the latest options while updating two screen-sharing-related ebooks – “Take Control of Screen Sharing in Snow Leopard” and “Take Control of Back to My Mac.” They’re available separately for $10 or together for $15 (look in the left margin of either book’s Web page for the discount link):

- In “Take Control of Screen Sharing in Snow Leopard,” Glenn documents the many Mac OS X screen-sharing options – in Snow Leopard and Leopard – including iChat, Bonjour, direct, and Back to My Mac, along with discussing Skype-based screen sharing, controlling your Mac from an iPhone app, and lesser-known options for working with older versions of Mac OS X and Windows. All these choices bring complexity, but you’ll learn how to identify, configure, and use the best screen-sharing approach for your needs. The 136-page book also includes troubleshooting information and assistance with router configuration.

- In “Take Control of Back to My Mac,” Glenn changes gears to focus deeply on the Back to My Mac feature available to MobileMe subscribers, since there’s a great deal to say about it. With Back to My Mac, you can connect from one of your Macs to another for file and screen sharing, making it possible, for instance, to snag a forgotten document or to control your Mac Pro from your MacBook while on a trip. You can also connect remotely to drives attached to an AirPort Extreme base station or Time Capsule. Or at least that’s the theory, since in practice, people have had huge trouble in getting Back to My Mac working. In this 95-page book, you’ll find essential

details on configuring common routers to work with Back to My Mac and learn about the security implications of using Back to My Mac.

The books work together as a pair if you want to take control of the entire Mac OS X screen-sharing enchilada, and they’re available independently. If you buy either one and then realize you want the other, you can use the Check for Updates button on the cover of each ebook to access a generous discount on the other.

(Those who have older versions of these ebooks should be sure to check their email – or click the Check for Updates button on page 1 of the ebook – to find out about upgrades. “Back to My Mac” is free to all who own an earlier version; “Screen Sharing” has an upgrade discount.)

Can You Get By with 250 MB of Data Per Month?

The iPad models that come with Wi-Fi and 3G will let users choose, on a month-by-month basis, whether to pay AT&T for 3G data service at one of two service levels. The unlimited plan is $29.99 per month, just like the iPhone’s data fee; the 250 MB per month plan (combined upload and download) is just $14.99 per month. Will that suffice?

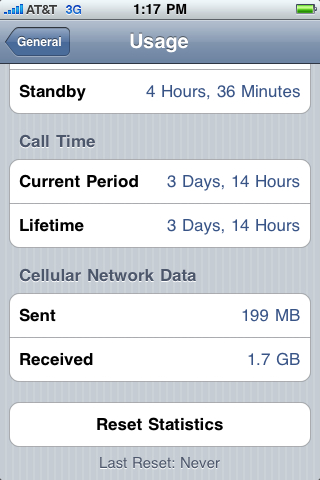

At first, I thought such a small amount of data laughable. I use my iPhone constantly, and must push vast amounts of data through it; with an iPad, I would surely use it even more. But I forgot that the iPhone tracks 3G usage separately from data sent over Wi-Fi until colleague Tom Negrino noted so in Twitter.

Tom wrote, “Checked iPhone’s 3G data use. Since Sep[tember], when I last reset the counter, 35 MB out, 171 in. iPad 250 MB plan OK.”

This prompted me to check my usage, which you can do in the Settings app by tapping General > Usage, and then scrolling down to the Cellular Network Data section and adding the two numbers there. As far as I can tell, I haven’t reset the phone’s usage statistics: I’ve used a combined total of 1.9 GB over 7 months or about 270 MB per month, just over the limit. I checked my AT&T account to see how much I used in January, a month in which I traveled with the iPhone and no laptop – just 150 MB total. Some research pegs average iPhone 3G usage at 500 MB per month. [And I’ve used just 589 MB since purchasing the iPhone 3GS in July 2009, well under the 250 MB per month limit. -Adam]

Neither AT&T nor Apple has said what will happen if you go over the 250 MB limit in a month. A rational approach would be simply to charge you $29.99 for that month and give you unlimited data for the rest of the month, but rational approaches have no role in the cellular industry – unless Apple has insisted on that as part of its continuing networking deal with AT&T. (The iPad could work on T-Mobile’s network in the United States, but not at 3G speeds, as the iPad doesn’t include the specific frequencies used by T-Mobile for 3G networking.)

One of our readers pointed out that Steve Jobs had said the AT&T plans would be prepaid; that’s in contrast to so-called postpaid plans. A postpaid plan requires that you pay for monthly service in the month before you use that service, but allows you to rack up additional usage and fees which are billed in the subsequent month. Prepaid service, by contrast, lets you use only the services that you have paid for, protecting you from additional fees. (Postpaid relies on credit checks and credit cards; prepaid typically allows many methods of payment, and delivers only up to the precise service paid for in advance.)

If AT&T is charging on what it calls a prepaid basis, but will bill for overages, that could get pricey. Most cellular carriers charge in increments of 5 cents per MB – $50 per GB! – for plans that have limits. A few carriers warn customers via texts, email messages, and sometimes phone calls as the data limit is approached. Without a cutoff, warnings, or a bump to the unlimited plan, expect customer horror stories to abound in the first few months after the iPad ships as people unknowingly rack up huge data bills.

AT&T will include free Wi-Fi access at its 20,000-plus hotspots as part of both of the iPad 3G plans, and I’m sure I’ve used my iPhone plenty at Starbucks and other free locations, as well as over my home and office Wi-Fi networks. (McDonalds’ is now entirely free for everyone, and represents nearly 12,000 of AT&T’s 20,000 locations, by the way; see “Find Free and Inexpensive Wi-Fi,” 23 December 2009.)

Wi-Fi is also being widely installed for commuters, often at no cost or as part of a low-cost plan. This includes trains, ferries, buses, and, one day, the BART system in the San Francisco Bay Area. Most airports are already included in AT&T’s network through roaming agreements.

If I were to buy an iPad, I would lean toward spending another $129 to get a 3G flavor just for the advantage of having access, when I need it, everywhere I go. The fact that I haven’t been overusing my iPhone’s 3G plan is useful to know. To make the $14.99 plan work, I’d just have to be slightly more careful about watching the meter.

Solving the Universal Access Color Problem

The free time afforded me by the summer holidays here in New Zealand – without doubt the most splendid aspect of being a teacher – has provided an opportunity to update my Web site, and I’ve been converting it from static HTML to WordPress (that’s a topic for a separate article; it was fun and not as hard as I had anticipated). I poked and prodded at style sheets, and was bothered by the colors I was seeing on the monitor of my slightly aging iMac. (And yes, it was a little freaky that this came on the heels of reading Joe Kissell’s article “Solving the Photoshop Elements Color Shift Problem,” 19 December 2009 – that was, however, an entirely different situation.)

A visit to my site will show you that I had placed a brace of sidebars in my design, and I had picked out a rather delicate shade of grey – #F0F0F0, if you will. But on my iMac’s screen, the grey of these sidebars was an unmistakeable, undeniable white. I pulled out my not-quite-as-old MacBook Pro and opened the same page; the sidebars were just the shade of grey I had hoped for. I looked on my wife’s iMac – she, being an actual designer, gets the newer machine, one of last year’s iMacs with the glossy screens – and saw the same thing that my iMac had displayed. I took a look on my Mac mini’s Cinema Display. Grey. I looked on my iPhone. Grey.

I was most baffled at this stage, so I decided to try enlisting the help of the TidBITS Talk mailing list, the folks there being a highly knowledgeable, helpful and just generally all-round groovy bunch of kids. Everyone – and over a dozen people were kind enough to take a look at my site and report back to me – said they were seeing grey (many of them were unable to spell “grey” correctly, but I overlooked this). One person did simply point out that my XHTML was flawed, but I blame that on Dreamweaver and WordPress.

So what, then, was the problem? Clearly the issue wasn’t with my site (XHTML issues notwithstanding). As far as I could tell, it was a hardware issue, but what was flummoxing me more than anything was the fact that it was an issue common to the two iMacs, but to, as far as I could tell, no other machines. In utter desperation (and, let’s face it, it takes desperation to fire up Windows), I launched Parallels Desktop on both computers. Internet Explorer 6 on the laptop showed the desired shade of grey but displayed the same page element as white on my iMac. My flummox capacitor was, at this stage, redlining. I decided to use Art Directors Toolkit (a highly useful

utility, albeit one that doesn’t believe in apostrophes), and found that both my computers believed that they were displaying #F0F0F0. It was increasingly apparent that the issue was with the individual computers; why, then, did two quite different computers have the same problem?

I searched, as best I could given my compromised Internet connection (see “Paying by the Bit: Internet Access in New Zealand,” 15 January 2010), for news of video issues related to the iMac. The computer in question has an ATI Radeon X1600 graphics card; I could find no reports of issues with the X1600, or indeed driver updaters for the card – that’s the kind of thing that Apple usually incorporates into an update to Mac OS X itself.

I went back to my Mac mini, took a screenshot of my site in Safari, copied that file to my iMac, opened it in Photoshop, and, again, saw white. This was, quite evidently, a problem with my iMac. I opened a blank document in Photoshop, and painted #F0F0F0; I saw white. I then opened a random selection of photos, and noticed that they seemed curiously posterised. I also saw that the colors in Photoshop’s color picker didn’t transition gradually from white in the top left corner to black in the bottom, the way they should; instead, any luminosity value above about 90 simply showed up as white. I buttoned in my favourite shade of grey; it was firmly in white territory.

I decided that I was fighting a losing battle, and went back to working on the mechanics of my site. I noticed, as a bit of additional freakiness, that when I was working in programs like Fetch that use alternately blue and white backgrounds for list items, the majority of a window would have a plain white background, but if I happened to have such a window in the background behind a foregrounded application, then the foregrounded application’s windows would cast a shadow – and, in that shadow, I could see the stripes of the background window. And, oddly, my wife’s iMac, which, you’ll remember, is of an entirely different vintage, exhibited the same behaviour.

Back I went to the TidBITS Talk list. Many people suggested re-calibrating my display; while I was grateful for the time everyone took to try to help me, at this point it was like calling an ISP’s tech support and being asked “Is your modem plugged in?” I had re-calibrated my iMac’s display about half a dozen times, to absolutely no avail other than to learn that trying to spot that little Apple logo on a stripey background is intensely annoying after a while.

But then I got a reply from the truly brilliant Paul Durrant: “Check in the Universal Access control panel that the ‘Enhance Contrast’ setting is at Normal.” A quick trip to the Universal Access pane of System Preferences – my first, I believe, since the days of Mac OS X 10.2 Jaguar; I’m fortunate enough not to need its features, so I’ve not opened it, as far as I can remember, in a very long time – revealed that the Enhance Contrast slider was, indeed, slidden one notch to the right. I dragged it to the left stop, and felt as though a veil had been lifted from my eyes.

I kicked up Safari, punched in my site’s URL, and – mirabile dictu! – it displayed perfectly. I opened every page on the site, just to revel in the delights of medium grey. I opened another random clutch of photos in Photoshop; I was reminded of the day I got my first pair of glasses and could suddenly see properly again.

The mystery lingered, though. How could I have activated enhanced contrast, if that control is buried in a part of the operating system that I usually have no need to use? The answer, I suspect, lies in the fact that this feature can be activated using a keystroke combination – Command-Control-Option-period increases the contrast; the three modifier keys with a comma pull it back. (Try pressing the keys repeatedly; it’s an interesting effect. But be sure to reset it in the Universal Access preference pane once you’re done.) Once Paul’s solution appeared, it was suggested that an application that involves a lot of convoluted keystroke combinations might result in features like Enhanced Contrast being accidentally invoked. But I’m not a

big gamer, nor is my wife, so I don’t think that’s the issue.

But my wife has a cat. (We both have a dog; the cat is hers.) Cat has a tendency, as cats do, to wander across my desk. Among the many annoyances this results in are the unplugging of hard disks, the scattering of assorted kit and, I now strongly suspect, the triggering of unnecessary actions through – I can just picture the little bugger doing it – a back paw pressing down on three neighbouring keys, and a front paw stretching out and pushing the fourth.

My computer now behaves, the cat is banished from the office, and I owe a huge thanks to everyone who tried to help me, Paul Durrant in particular, who actually identified the issue. Now I’ll see about fixing the XHTML…

Is the iPad a Kindle Killer?

Media companies leak like sieves, so it was known for a long time before the iPad announcement that Apple was having conversations with book, newspaper, and magazine publishers about what those firms would want in an ideal device and in ideal software. We saw the first fruits of those discussions at the iPad launch, with the New York Times demonstrating a hastily revised demo app, and with Apple’s bundled iBooks app.

Apple didn’t discuss magazine and newspaper subscriptions, but the New York Times demo showed that Apple was clearly looking to the existing app approach coupled with in-application or one-time fees to suffice for that model.

For books, however, there’s a new app: iBooks. The program combines a bookstore and a bookshelf, enabling you to purchase books and download them for reading on the device. (The iBookstore was not yet enabled on the iPads available at the 27 January 2010 media event, so I couldn’t test it.)

While the iPad has the potential to render the Amazon Kindle 2 and Kindle DX obsolete, Amazon’s Kindle books are not limited to the Kindle itself; special software lets you read any book that’s available for the Kindle on an iPhone or Windows system. (The Mac OS X software has been “coming soon” for many months now; BlackBerry software is still on the way.)

Both publication subscriptions and book sales put the iPad into direct competition with Amazon – for any profit Amazon makes from selling Kindle hardware readers and for the income from selling content.

The iPad will certainly run the Kindle for iPhone app, and Amazon may trump Apple on book pricing, as the Seattle book and media seller has so far been willing to subsidize the cost of lower-margin or negative-margin ebooks – books that cost them money to sell – to keep overall sales strong. But Apple’s revenue split – apparently 70/30 for the publisher, just as with the App Store – trumps Amazon’s current general 50/50 split for large publishers.

Since I can’t evaluate iBooks on the basis of its available catalog, the shopping experience, or pricing, I have to focus on four elements: the reading and interface experience, the screen technology, networking and Internet access, and the desire of publishers to have more control and reap more profit from ebook sales than Amazon offers in the Kindle model.

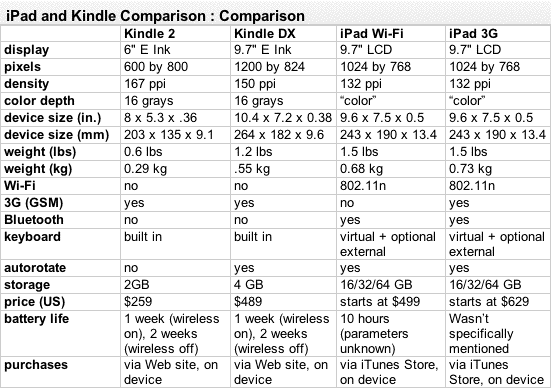

For a head-to-head hardware comparison, I’ve compiled a small spreadsheet (which you can also view as a Google spreadsheet).

(Disclosure: I worked at Amazon for six months as a senior manager in 1996 and 1997. I left before I vested stock, and own no stock in either Amazon or Apple. Besides Jeff Bezos, I’m not even sure if anyone I worked with at the company is still employed there.)

Reading — The simplest part of this whole ebook reader equation is the actual reading. No matter whether you’re absorbing text on a Kindle device, the Kindle for iPhone app, or an iPad, there’s little friction between you and the words.

Syncing, storing, and accessing library. The Kindle readers and iPhone software maintain a list of media you’ve downloaded. You can download media you’ve purchased but aren’t currently storing at no additional charge. There’s also no charge to sync over USB. Any Kindle software or hardware registered to your Amazon account can download and read any book you’ve purchased or media subscription (subject to hazy limitations).

iBooks might use iTunes to maintain its library, as iTunes manages music, podcasts, movies, and acts as a conduit for photo galleries; Apple has so far been unclear about whether or not iTunes will manage books too. Nonetheless, Apple will provide some software that will enable multiple iPhone OS devices under your control to sync books you’ve bought or loaded. Unlike Amazon, Apple considers it your problem to maintain and back up your media library; lost songs and videos can’t be re-downloaded. Of course, the fact that iPhone OS devices back up every time they connect to a computer makes data loss less likely.

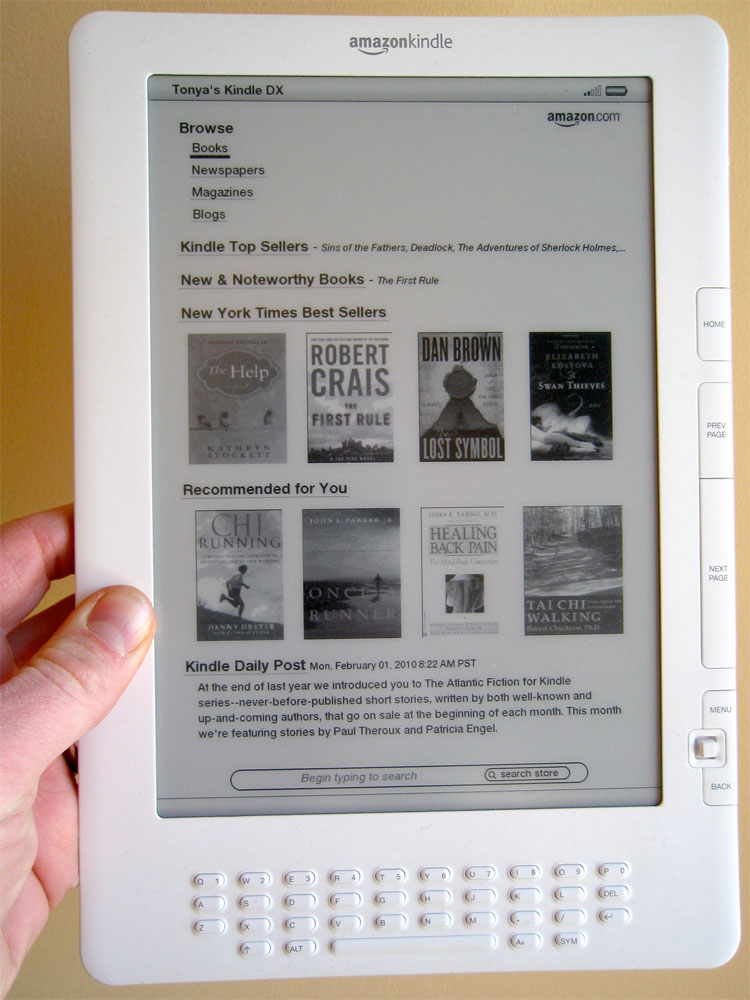

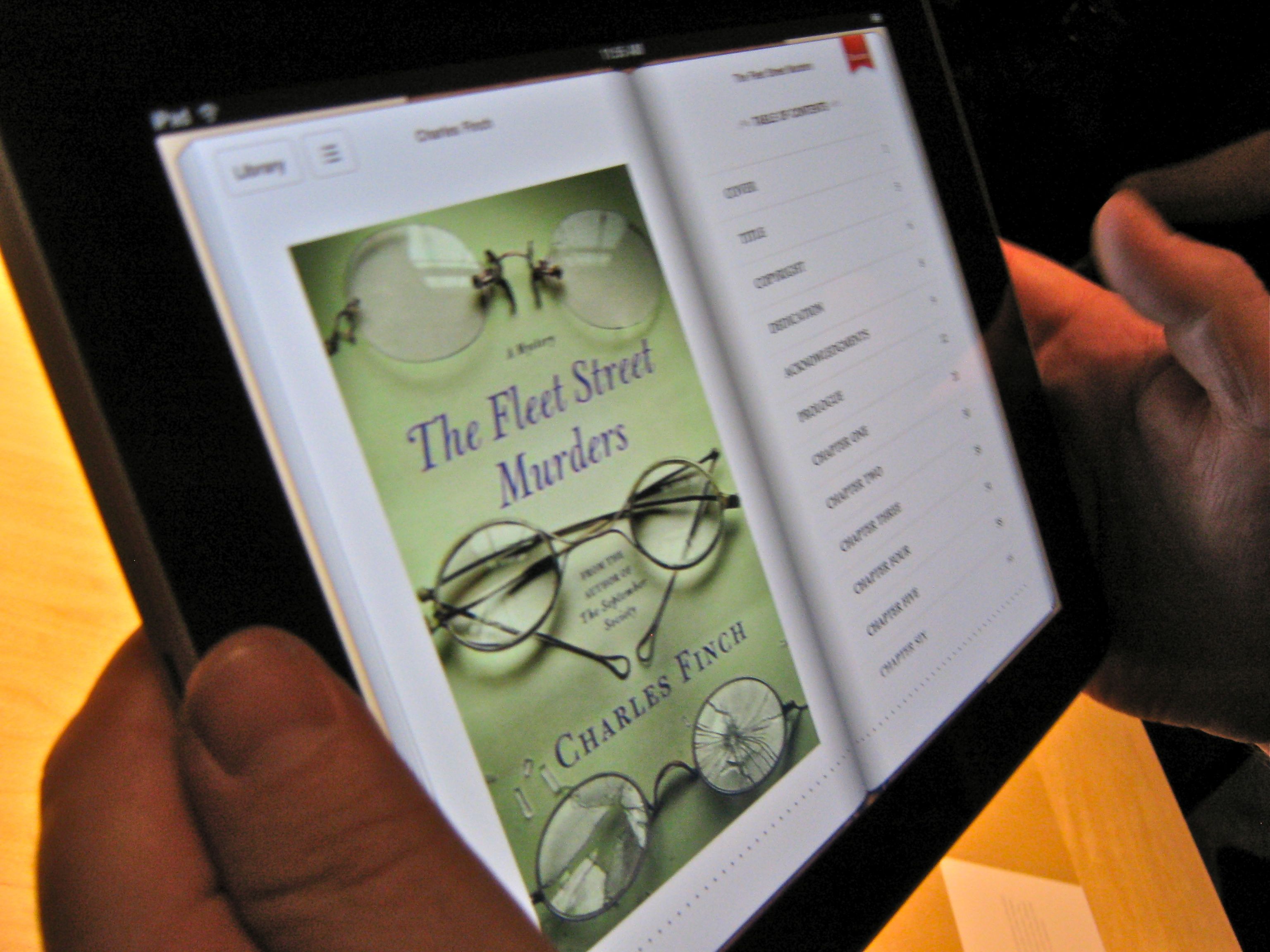

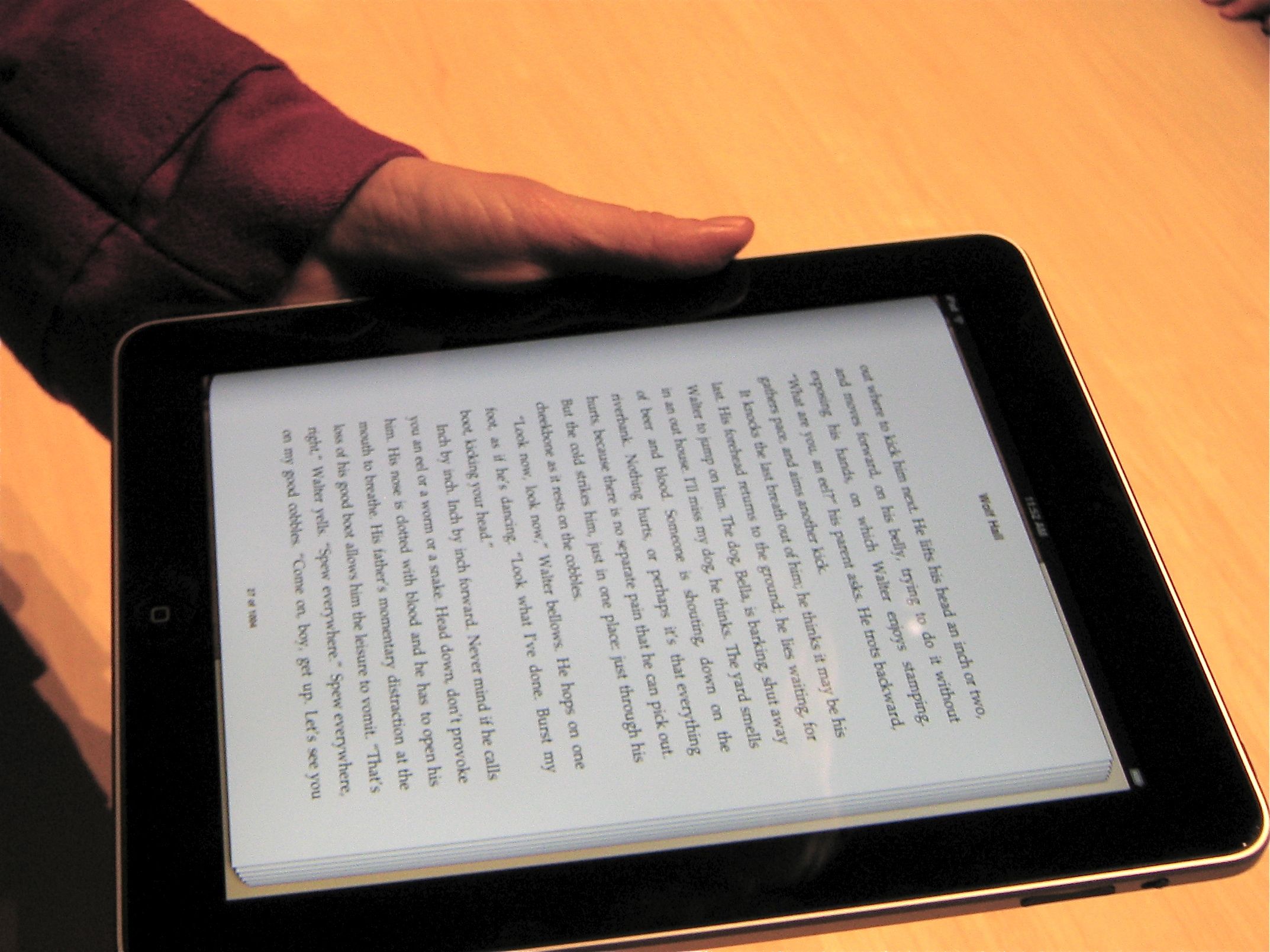

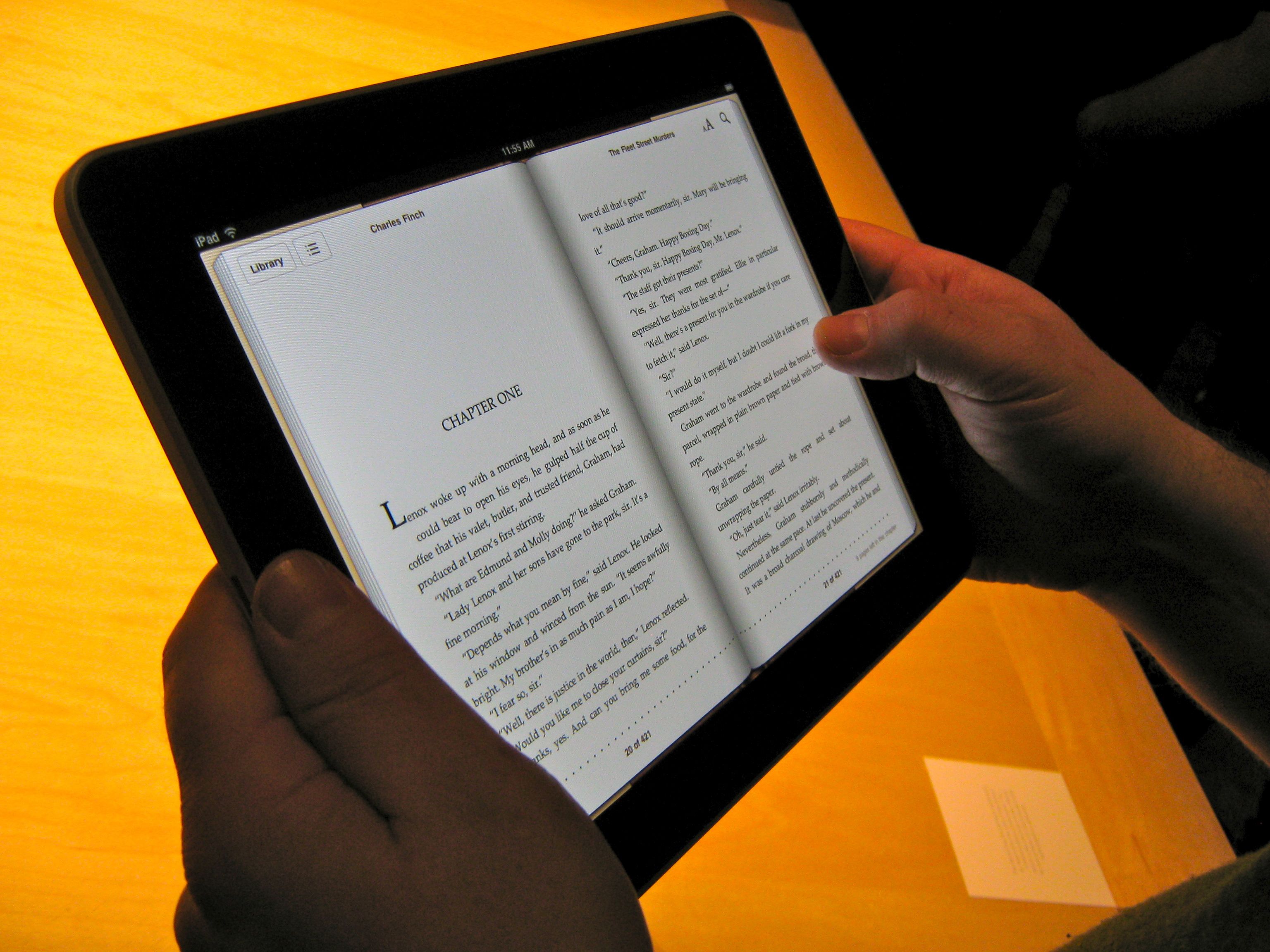

The interface for picking stored books to read on the iPad probably demonstrates at the outset what the Kindle is up against. You can see how book covers appear on a Kindle DX in this image. Contrast that with the iPad, which uses a bookshelf metaphor to show browsable shelves of full-color covers.

(I’d be remiss if I didn’t note that Apple appropriated much of the look and feel of the bookshelves from Delicious Monster’s Delicious Library software. That application didn’t invent the concept of using bookshelves, but it seems clear where the iBooks app got its visual inspiration.)

Amazon and Apple use different digital rights management systems to prevent books from being read on other devices or in other software. Both platforms can, however, read unencrypted files in a number of major ebook formats. Amazon requires that such files be transfered via USB, or via a special email address dedicated to each Kindle reader that requires additional fees.

Apple hasn’t yet explained how non-purchased ebooks can be added to the iBooks app. Apple supports PDF display in iPhone OS, but that’s only as an email attachment or within programs like GoodReader, AirShare, or Dropbox that open stored files. It would be lovely if iBooks would manage and allow PDF reading.

Reading interface. The Kindle’s main function is to read, and Amazon has made that process simple. Reviewers – including yours truly – expressed disdain for the original Kindle design, notably its poorly placed and sized previous/next buttons. The design was notably improved in the Kindle 2 and carried through to the Kindle DX.

Select a book to read, and the display opens in portrait view on the Kindle 2, or can auto-rotate to portrait or landscape (a single column’s width) on the larger Kindle DX. Amazon tracks the last position you read in a book regardless of which device or software program you last used. If you switch from a Kindle reader to the iPhone app and then to Kindle for Windows, you never lose track of where you’re at in the book.

On the Kindle hardware, changing pages involves using hardware buttons that you press to move forward or back. Other menus let you reach the table of contents. The E Ink hardware offers an irritating flash as the page is rewritten for each turn. For smaller changes – such as a menu appearing – only part of the screen is rewritten, the flash isn’t noticeable, and the Kindle momentarily appears fast.

Words can be selected in a somewhat awkward manner using a stubby joystick and looked up in the dictionary. You can also search the contents of the book for matching words or phrases.

You can annotate selected text, and your annotations are stored and synced across whatever devices you own. Annotations can’t be extracted from Kindle to other formats, however. You can choose among six sizes for type. Books are justified ragged right or fully across the page (leaving rivers of white) based on the publisher’s preference, apparently, and cannot be changed.

The Kindle for iPhone app uses swiping gestures and a draggable position indicator to move through a book, and offers five type sizes from which to choose.

iBooks is equally simple, but designed around the multitouch experience. Tap a book in the bookshelf to read, and it opens to where you left off. We don’t yet know if Apple will sync the last-read position among devices registered to your account, but that’s the behavior used for listening to podcasts and audio books. You tap or swipe to go backwards and forward through the book. Swiping slowly lets you see the page curl and turn. You can select among five fonts and several sizes to read books. You can also quickly navigate to the cover and table of contents.

iBooks shows either a single page in portrait view or side-by-side pages in landscape orientation. Black-and-white and color images, as well as video, can be embedded in books, although I didn’t see any video in the sample books I looked through. Full justification appears to be the only formatting option.

The version of iBooks I saw is certainly not what will ship, but the omissions at the launch event were notable: no annotations or highlighting, no way to look up references, and no bookmarks. There was a search icon, but the feature wasn’t yet activated.

Amazon got around the “where in the book am I?” problem by indexing a book using reference locations. These reference units allow sync across devices by referring to the same unit, regardless of format and type choice.

Apple, so far, is using absolute page numbers derived from the current typeface and size. This would make it difficult to refer to a precise location in an iBooks title, and would be a particular problem with textbooks that may appear in ebook and print formats and be used interchangeably by the same students in a class. Nevertheless, most readers won’t care at all, since by far the main use of page numbers in the real world is to remember your place in a book, something the iBooks app should just do for you.

Screen versus Screen — Amazon made hay from using the E Ink screen for its Kindle, despite the technology’s previous inclusion in the Sony Reader. E Ink has a tremendous advantage over LCD displays in two ways: persistence without battery drain, and no need for backlighting.

When pixels are changed from one shade to another, the screen technology causes a fixed physical change, as opposed to varying the charge applied as in an LCD display. An E Ink display’s image remains in place without any additional power consumed. That’s a big reduction in battery use right there.

The relatively high contrast without backlighting also makes for easier reading for some people – many of our friends on Twitter swear by the ease of E Ink screens on their eyes – while also consuming less power than a backlit LCD. Like paper, the screen can be read from varied viewing angles, too.

However, those two advantages seem to be eroding. The iPad uses a color LCD with a wide range of viewing angles. I noticed the angle issue at the iPad launch: you could see an iPad at an extreme rotation and still make the screen out clearly, even from many feet away, or hold one up closely and move it around without losing screen acuity.

We have only Steve Jobs’s word so far on battery usage: he said 10 hours, and apparently meant 10 hours of real usage, as he cited watching movies from San Francisco to Tokyo. If so, that’s a huge improvement over any comparably sized and featured device.

While the Kindle devices promise one week of reading with the wireless 3G modem turned on and two weeks with it turned off, the Kindle is used for far fewer activities. I’d imagine that with wireless off and just reading, the iPad will have a far longer lifetime than the 10 hours cited. You can also adjust backlighting on the iPad to reduce battery drain, just as on an iPhone or iPod touch.

The use of an LCD allows books to include videos and full-color images, which makes possible the correct reproduction of certain types of books, like graphic novels and anatomical textbooks, which simply wouldn’t work on the Kindle’s grayscale screen.

I have no trouble reading a backlit display all day long, but as noted above, many people seem to prefer the Kindle, noting especially how well the Kindle readers work in daylight conditions. LCDs often perform poorly with any kind of direct light or glare. Whether this advantage of the Kindle screen is significant depends on your usage patterns. If you do a lot of reading at the beach, it’s important, but if you prefer a comfortable couch inside, it’s largely irrelevant. On the flip side, reading on a Kindle in bed requires additional light, whereas the backlit iPad won’t.

From the screen size and pixel density standpoint, the difference isn’t great.

- The Kindle 2’s 6-inch screen (measured diagonally) has 600 by 800 pixels at a 167 pixel-per-inch (ppi) density.

- The Kindle DX has a 9.7-inch screen, 1200 by 824 pixels in size, and a 150 ppi density.

- The iPad uses a 9.7-inch screen with 1024 by 768 pixels at a 132 ppi density.

The iPhone and similar smartphones have about a 167 ppi display, while newer phones, like the Droid, feature even higher resolutions. The higher you go, the closer to paper a display resembles: type and graphics appear smoother.

I didn’t notice any artifacts except in the page curl in iBooks with the lower-density iPad screen.

Networking — Amazon broke through the indifference to ebook readers by building a cellular modem into every Kindle. More recently, it switched its carrier partner and modem technology from Sprint, which uses a network standard widely employed only in the United States, to AT&T, which uses the worldwide dominant GSM standard. Both current Kindle 2 and DX versions use the GSM modem and can work (with different delivery prices) on over 100 GSM networks worldwide.

Amazon lets you use the cell modem only to purchase and download content or subscribe to paid content. Free content that can be converted or read in native format on the Kindle 2 or DX must be transferred while the Kindle is plugged in via USB to a computer. The Kindle mounts as a USB drive, and synchronization is manual. On the other hand, you don’t have to sync the Kindle to a particular machine. You can also send documents to your Kindle via email, at a cost of 15 cents per megabyte, rounded up to the next whole megabyte.

Amazon’s avoidance of Wi-Fi is odd, because Wi-Fi networks are abundant, and ever more of them have turned free-with-purchase or entirely free. (See “Find Free and Inexpensive Wi-Fi,” 23 December 2009.)

The iPad will come in two versions. The less-expensive flavors, with price determined by built-in storage, have only 802.11n Wi-Fi, the fastest wireless networking version currently available, and one that is supported by all three Apple base station models released since 2007. As with the iPhone and iPod touch, it seems clear that you won’t be able to sync media over Wi-Fi, however, but must instead use USB to connect to a single copy of iTunes.

Apple will also offer iPad models that support 3G technology, using GSM as in the iPhone and adding $130 to the price of each iPad, but requiring no service plan on purchase and no service contract for use in the United States.

Amazon bundles the cost of each download into the price of the books and subscriptions it sells; it’s probably pennies per transaction given the 15 cents per megabyte cost Amazon quotes in general. Apple, by contrast, struck a deal with AT&T to allow 250 MB of use per month for $14.99 and unlimited use each month for $29.99. For a general-purpose device, this makes far more sense as a plan, of course. (AT&T’s 3G service is coupled with free Wi-Fi access at its 20,000-plus hotspots, although nearly 12,000 of those are McDonald’s restaurants that have already switched to free service as of mid-January 2010.)

Given that Apple is requiring iPad purchasers to pay the cost of Internet transport, Apple has no secondary payments to network operators, giving it a small slice of additional revenue to play with when pricing books.

The Kindle fares far more poorly in its network pricing outside the United States. Amazon charges a small fortune – sometimes dollars per book – for downloads of books on a U.S. Kindle taken overseas, and for titles purchased on non-U.S. Kindles in the country in which the Kindle was bought (see “Amazon Extends Kindle Beyond United States,” 8 October 2009).

Apple will have no such problem. Wi-Fi can always be used as an alternative to 3G. Apple will strike carrier-specific deals akin to the AT&T arrangement as it expands its 3G plans for the iPad outside the United States later this year.

Publishers — This last of these four elements is the trickiest, because it’s not about you – unless you run or work for a media company – but about the book, magazine, and newspaper companies that are worried in various ways about the future of their industries.

Yes, the biggest of these firms used to reap huge profits and control their fortunes; now, newspapers in particular appear to be sliding down a ramp into bankruptcy and obsolescence. That’s why the iPad has assumed disproportionate interest – especially among the newspapers covering Apple.

Amazon may have sold “millions” of Kindles according to a remark by company founder Jeff Bezos, but that’s still a drop in the electronic bucket. The Kindle penetration couldn’t begin to produce enough revenue on the subscription side, even if it’s pulling in many millions of dollars of ebook revenue. (Bezos said millions of people own Kindles, but his choice of words might mean he’s counting all members of households that have Kindles as “owners.” Consumer electronics analysts have pegged the Kindle at more like a million units sold to date, and Amazon has coyly refused to give solid sales figures.)

Publishers also hate Amazon’s terms on subscriptions and book pricing. Amazon gets 70 percent of the revenue from subscriptions, which seems excessive for what it delivers. The reason there are so few subscriptions available on the Kindle – relative to the number of periodicals in the world – is that Amazon hasn’t offered a particularly compelling deal.

Media firms don’t want to get locked into the bad revenue split, and can already get visitors to their sites where they display advertising that provides direct revenue. The New York Times earned $100 million in online advertising in 2008, according to the Wall Street Journal.

Apple plans to flip the revenue split around, although, so far, it doesn’t seem to be on the path to offer automatic downloading of new content. Kindle subscriptions include downloading new media content as it’s released, so you don’t need a network connection at the time you want to read the latest New York Times article.

At the iPad launch event, representatives from the New York Times showed off a hastily revised iPhone app that took advantage of the larger screen for better layout, integral videos, and other elements. The model Apple is pushing is clearly that periodical publishers should create custom iPhone OS apps designed for the iPad, and Apple will keep 30 percent of subscription revenue as it does now for in-app purchases and flat-rate app sales.

Because Apple hasn’t released any specific information about periodical subscriptions, I’m reading the tea leaves and extrapolating, of course.

Book revenue is trickier. For major publishers, Amazon pays 50 percent of the list price of the current cheapest print format book. If a book is only in hardcover – a new release like a Dan Brown blockbuster – the cover price might be $30 and Amazon pays $15. When that book goes into paperback format and sells for $12, Amazon pays just $6.

However, Amazon wants ebooks to be cheap, and thus charges $9.99 for books still available only in hardcover. It subsidizes the price of these books to set the overall price low, and reaps its profit margins from cheaper books for which it makes its full 100-percent markup – or even more. Since Amazon is the dominant ebook seller, it may be using that position to charge more than double its wholesale cost for less-expensive books.

Just before the iPad launch, Amazon offered a new set of terms for smaller publishers that gives 70 percent to the publisher, in exchange for a requirement that the book is priced between $2.99 and $9.99, isn’t sold for less at other ebook stores, and is at least 20 percent below the cheapest print edition. (See “Amazon Opens Kindle to Developers, Changes Royalties,” 21 January 2010.)

Apple reportedly wants just 30 percent of subscription and ebook revenue, and doesn’t want to set book prices, although the $13 to $15 range is more likely to be the top instead of the $10 line Amazon has tried to hold.

As I write this, Amazon is fighting a public battle with Macmillan, one of the largest U.S. publishers. Macmillan wants to set a higher list price for newly published books as they appear in electronic form (that $13 to $15 mentioned earlier) and give Amazon 30 percent of that list price. If Amazon doesn’t want the new terms, Macmillan would offer a far smaller catalog than it currently provides when it starts its new ebook pricing system in March 2010. (Macmillan is one of the five publishers Apple said it had signed up at the iPad launch.)

Macmillan is in part trying to prevent the erosion of revenue from the big push for new big books in hardcover. If Amazon can sell such titles for $9.99, even at a loss, and even if Macmillan makes $15 from Amazon selling at that price, it sets the wrong expectation, and overturns some of the economics for both blockbusters and mid-range books. (The blockbusters’ margins make possible the more interesting books that sell vastly fewer copies.)

Amazon balked, and not only pulled Macmillan’s ebook titles, but also stopped selling all Macmillan print books temporarily. That’s the biggest hissy fit I’ve ever seen a company pull. Macmillan’s head issued a letter to its authors and illustrators (and their agents) which noted that what Macmillan wants is control over its own destiny. I also like author John Scalzi’s take in “Amazon.fail,” in which he enumerates the contempt shown by the firm.

On the face of it, this seems like a bad deal for consumers. Wouldn’t you rather pay $10 than $15 for a book? Absolutely. But in the long run, Amazon would achieve de facto control over book pricing, which would hurt small and large publishers. It also locks in users who become accustomed to lower prices.

But it’s not that Macmillan wants to sell books for $13 to $15 forever; rather, “Pricing will be dynamic over time.” That is, Macmillan can price books in response to demand, instead of being stuck in whatever pricing system Amazon wants to impose; it frees Macmillan and Amazon from structuring pricing around print book list prices, too.

With more control on the supply side, Macmillan can reduce prices as demand lessens. Those who desperately want a book immediately might pay $15 at its launch; Macmillan would also guarantee print and ebook editions would be issued at the same time. If you can wait, you might pay less and less.

As science-fiction writer Charlie Stross – who writes for a Macmillan imprint and whose own books were pulled – wrote, “Such a system would allow them to get a lock on the price elasticity of demand, and thus work out the price point at which they can maximize book sales.”

This is good for readers, writers, and publishers, as well as ebook distributors, including Amazon and Apple. More books will be sold this way, and more revenue directed at the creators, not the middlemen.

For its part, Amazon is saying this is about Macmillan setting its ebook prices “needlessly high.” But the firm also notes, “Amazon customers will at that point decide for themselves whether they believe it’s reasonable to pay $14.99 for a bestselling e-book.” That’s right: they will! That’s how the market works. And because Amazon can sell Kindle ebooks to read on an inevitable updated Kindle app for iPad, we can see market choices directly on that one device.

Amazon said it will capitulate to Macmillan’s pricing structure, but as I write this only the print editions of Macmillan’s titles have been restored for purchase; ebooks remain “shelved.”

Part of my interest in this area is that the “in-print” catalog of ebooks from Amazon, Sony, and Barnes & Noble remains pitifully small compared to all in-print books. There are perhaps as many as three million books available from the trade and publishers in the United States, but Amazon offers fewer than 10 percent in its catalog. The reason is partly its revenue split and interest in control of the market.

I suspect that Apple’s emergence into the ebook market precipitated this Amazon temper tantrum. Apple may be able to offer publishers more of what they want than Amazon, and Amazon is freaking out. Apple, after all, has not viewed music, video, or app sales as profit centers; instead, the company’s approach is to sell devices (with higher margins), like the iPad and iPhone, that excel at playing media. (Amazon’s behavior reminds me strongly of this November 2007 Crazy Apple Rumors Site parody article, “Apple e-Book Reader Captures the Market.” [Language not safe for work.])

Kindle Co-opetition — In the end, Amazon is a bookseller, and its foray into hardware shows that it’s better at moving media than making machines. The Kindle has evolved into a nice piece of hardware that gets great reviews from those who keep it.

But, put bluntly, the Kindle DX just doesn’t compare favorably with the iPad in any way other than battery life and screen visibility in sunlight; the Kindle 2 benefits from being smaller and cheaper. And the Kindle ebook library may offer titles at a lower price, though Amazon may be forced to capitulate on that.

When the iPad ships, we can get a better sense of how it will be received. If most people consider it a glorified book reader with a Web browser, then the ebook portion of the iPad may be vastly more important than if people instead see it as a new kind of computing device in which ebooks are just another bullet point.

It’s interesting to note that Apple’s dominance of the downloadable digital music market led music publishers to cut deals with Walmart, Microsoft, and Amazon to provide full catalogs without any digital rights management – partly because Apple refused to compromise on pricing!

The music publishers forced a crack in the digital music world, and incidentally gave us what we wanted in terms of removing DRM from music, while creating a range of music and album prices that averaged just above what the one-price-fits-all model had previously provided.

Strange that Amazon doesn’t see the poetic reflection.

TidBITS Watchlist: Notable Software Updates for 8 February 2010

FontExplorer X Pro 2.5 — Linotype has released a major update to its professional font management tool FontExplorer Pro. The user interface has been updated and streamlined, a new widescreen mode enables the user to set the Preview area off to the right, a new transparency mode can be used to overlay and preview fonts in a working document, and printing is now enabled. Also, users can now tag their fonts for easier organization. Finally, several bugs related to the Apple font panel have been resolved, support for Adobe InDesign CS3 and CS4 has been improved, and various unspecified crashing bugs have been fixed. Full release notes are available on Linotype’s Web site. ($79 new, free update, 28 MB)

Read/post comments about FontExplorer X Pro 2.5 .

Espresso 1.1.1 — MacRabbit has updated its Web authoring application Espresso with a handful of minor tweaks and fixes. Version 1.1.1 adds pixel dimensions to Image Preview, the capability to show hidden files in project listings, and support for some JavaScript commands in previews. Also, regular expression searches are now supported in Find in Project, Sugars now load faster, window sizing is improved when dragging multiple tabs out of the workspace, and a crashing bug related to SFTP publishing has been fixed. A full list of changes is available on MacRabbit’s Web site. ($79.95 new, free update, 10.3

MB)

Read/post comments about Espresso 1.1.1.

iPhone OS 3.1.3 — Apple has released iPhone OS 3.1.3 to provide a couple of performance improvements and address several security threats. Changes include improved accuracy on the iPhone 3GS’s battery level display, a fix for a bug that prevented some third party programs from launching, and a fix for an issue that caused application crashes when using the Japanese Kana keyboard.

Also eliminated are three security vulnerabilities that could lead to application crashes and arbitrary code execution after playing maliciously crafted audio files, viewing maliciously crafted TIFF files, or visiting a maliciously configured FTP server. Another fix prevents remote image or video content being loaded in Mail even when remote image loading is turned off. And finally, the update blocks a vulnerability that could enable an attacker with physical access to a locked iPhone or iPod touch to gain control of personal data via the recovery mode. The update is available only via iTunes. (Free, 291 MB)

Read/post comments about iPhone OS 3.1.3.

iTunes 9.0.3 — Apple has released a small but helpful bug-fix update for iTunes. Version 9.0.3 fixes an issue that prevented the “Remember password for purchases” setting from being enabled, addresses problems with syncing certain smart playlists and podcasts with unspecified iPod models, and resolves a bug that caused problems in recognizing connections with some iPods. Apple says the update also improves general stability and performance. The update is available via Software Update or from Apple’s Web site. (Free, 90.82 MB)

Read/post comments about iTunes 9.0.3.

27-inch iMac Display Firmware Update 1.0 — If you own a 27-inch iMac that’s afflicted with the cursed screen-flickering problem, Apple’s 27-inch iMac Display Firmware Update 1.0 will come as very good news. The update claims to correct the iMac’s firmware to ensure proper display performance, eliminating the widespread flickering issue marring the displays of many 27-inch iMacs (see “New iMac Screens Cracking and Flickering,” 10 December 2009). Be sure to follow Apple’s warning not to turn your computer off during installation. More information regarding

installation is also available on Apple’s Web site. The update is available via Software Update or the Apple Support Downloads page. (Free, 294 KB)

Read/post comments about 27-inch iMac Display Firmware Update 1.0.

ExtraBITS for 8 February 2010

Not surprisingly, our focus this week was on the iPad, with links to a podcast with Adam, Tonya, and Andy Ihnatko; an interesting article from Macworld’s Chris Breen suggesting how the iPad will be used in everyday scenarios; and the news that Amazon is looking to add touch capabilities to the Kindle. Plus, AT&T is relaxing its limitations on what can be transferred over 3G, and will be allowing both streaming video and voice-over-IP calls. Finally, Apple has added iPhone apps to the iTunes Preview Web site, a security firm has identified a theoretical vulnerability in the iPhone OS, and it turns out that Macs control the market for $1,000 computers.

Podcast Discussion of the iPad, Amazon, and Ebooks — In this two-part MacNotables podcast, Adam, Tonya, and the inimitable Andy Ihnatko joined host Chuck Joiner to discuss the dust-up between Amazon and Macmillan. They segued from there into a discussion of the Kindle, the ebook market, and the iPad in general. Well worth putting on your iPod for the evening commute.

Apple Enables Web-Based App Store Previews — Apple’s iTunes Preview Web site has enabled Web-based previews of many titles in the App Store, such as Tap Tap Revenge 2.6, linked here. Aside from making it easier for users to check out apps without having to leave their browsers and launch iTunes, Apple undoubtedly wants to encourage Web search engines to link into the App Store. Given that, it’s not surprising that the iTunes Preview site still pushes you to iTunes whenever it gets the chance.

Stay Alert for iPhone Phishing Attacks — Security research group Cryptopath has discovered a vulnerability in the way the iPhone OS handles authentication certificates that could enable potential attackers to gain access to user data. To take advantage of this flaw, an attacker would have to trick users into downloading a malicious file under the guise of a legitimate update. While there are no reports of this security flaw currently being exploited in the wild, be extra careful when opening unverified links or files until an official security update is released.

Slingbox for iPhone Will Work over 3G — AT&T and Sling Media have worked out a deal where SlingPlayer Mobile app for iPhone will be able to stream content from an individual’s SlingPlayer digital video recorder over a 3G network. AT&T also said it has worked out streaming video guidelines for 3G, which other developers will have access to in the second quarter of 2010. The updated version hasn’t yet been approved and posted by Apple, but it’s unlikely to hit other snags.

Amazon Looking to Add Touch to the Kindle — The New York Times reports that Amazon has purchased the tiny startup Touchco, which was working on a next-generation touch-screen technology that could be used to create full-color touch-screen displays that would be significantly cheaper than current touch screens. Gee, do you think Amazon may be acknowledging that slow E Ink screens aren’t going to be sufficient to compete with the iPad?

Skype Plans VoIP in 3G in Next iPhone Release — Skype said in a blog post (with a brief video interview) that Apple’s iPhone OS 3.2 update, currently available for testing with developers, provides the changes necessary to allow voice-over-IP calls using a 3G connection. Apple had previously not allowed this, but U.S. regulators pressed for a change, which Apple has made. Skype says the new release will come when it is confident of its software’s capability to make high-quality calls.

Chris Breen Ponders the iPad’s Potential — So where does the iPad fit in the world of gizmos and gadgets? Macworld’s Chris Breen shares some thoughts regarding the iPad’s potential uses in every room of your house, as well as when you’re on the road or in the air. His visions suggest that third party accessories will be essential for integrating the iPad into our lives, much more so than the iPhone or the MacBook.

90 Percent of $1,000 Computers Are Macs — Joe Wilcox on Betanews reports on numbers gathered from research firm NPD showing that 9 out of every 10 computers priced at over $1,000 sold in Q4 2009 were Macs. This is evidence of Apple’s success in positioning the Mac as a premium brand, but NPD also points out that most of the growth in the PC market is at the under-$500 price point. With Apple posting record sales and profits quarter after quarter, we don’t see the company worrying about the low end of the market.