TidBITS#1110/23-Jan-2012

Apple’s special event last week may have been targeted at the education market, but the new iBooks 2, iBooks Author, and iTunes U apps — and how they’re being seen by both those who create books and those who read them — dominate this week’s issue of TidBITS. Adam covers the basics of Apple’s announcements, and also looks at why much of the consternation is happening because people are missing that Apple is aiming everything at the education market. Michael Cohen also weighs in with commentary about why iBooks Author will be a big deal in education, but taking the opposite view is physics teacher Steve McCabe, who argues that iBooks textbooks offer a warmed-up take on twenty-year-old ideas. In our own publishing news, it may not be an enhanced iBooks textbook, but Glenn Fleishman’s new “Take Control of Screen Sharing in Lion” still has all the help you need to choose and use the right method of screen sharing for your needs. And speaking of Glenn, he also runs down the latest changes in AT&T’s data plans for iPhones and iPads. Notable software releases this week include iTunes 10.5.3, Typinator 5, QuarkXPress 9.2, and Default Folder X 4.4.8.

No TidBITS Membership Signups in Person at Moscone

We said in “TidBITS Events at Macworld | iWorld 2012” (17 January 2012) that we’d be doing in-person TidBITS membership signups at Moscone West on Friday at 3:00 PM. That had been a last-minute decision, and it was ill-considered. Our friends at IDG World Expo have asked that we don’t do this, since we’re not paying for booth space, which is what’s necessary to conduct business at the show, and that’s entirely reasonable. So we’ll still show up near the escalators in the lobby to chat, but we won’t be taking memberships in person at Moscone.

If you see me somewhere else outside of Moscone, that’s fine, but we won’t be trying to set up any other particular meeting spots this year (though it would be fun to try the Square, it really is easier all around if you sign up online, where we’re still gunning for our goal of 2,000 members in January). Sorry if this change has caused any confusion, and our apologies to the IDG World Expo folks.

AT&T Raises Data Plan Prices for New Customers

AT&T is raising the price of its two smartphone data plans by $5, but increasing the monthly usage allotment by 50 percent at the same time. iPad service plans were also modified in a more convoluted way. Until 21 January 2012, the tiered smartphone plans cost either $15 per month for up to 200 MB of upstream and downstream data used, or $25 per month for up to 2 GB. Additional data cost $15 per 200 MB on the $15 plan and $10 for 1 GB on the $25 plan.

On 22 January 2012, the lower tier rose to $20 per month, but now includes 300 MB of data. Additional units of 300 MB cost $20 each. The next tier jumped to $30 per month for 3 GB of data, but picked up the previous plan’s $10-per-gigabyte overage charge. And finally, AT&T still charges extra for tethering and the personal hotspot option: it’s listed as a separate plan that costs $50 for 5 GB. Additional units of 1 GB also cost $10 with this tethering tier.

You can remain on your current plan — whether unlimited, 200 MB, or 2 GB — indefinitely, but the moment you switch to one of the new options, you can never return to unlimited service or the previous tiers.

AT&T offers extremely nice options for changing your service plan mid-month at no charge via the myAT&T app, its Web site, or by calling customer service. You can typically back-date a data plan to the first of the month, which can be a significant savings on the 200 MB or 300 MB plan if you burn through data, or pro-rate service from the current day of your billing cycle, if you expect to use much less or much more data through the end of a month. (In some cases, you may need to call or use the Web site to make the change, rather than modify service via the app.)

AT&T could adjust your service level to the optimum price each month with no jockeying on your part. This would increase customer satisfaction, which reduces churn (the number of customers leaving), and decreases marketing, retention, and account costs. But apparently AT&T, like other major cellular carriers, isn’t interested in this — presumably the companies feel the extra income is worth the customer annoyance.

Meanwhile, AT&T has stuck with its plan to throttle to EDGE speeds (about 200–300 Kbps) the top 5 percent of bandwidth users among its remaining unlimited subscribers, who pay $30 per month. Based on numbers provided by AT&T in earlier press releases, 20 million plans remained on the unlimited level in mid-2011. The throttling affects as many as 1 million users each month. On Twitter, one such capped user said he had used only a smidge above 2 GB last month and was throttled.

The new 3 GB tier at the same price as unlimited data may be an attempt for AT&T to lure unlimited customers who are being throttled to migrate to the metered way of doing things.

On the tablet front, there are also new iPad plans. The lowest level — 250 MB for $14.99 — remains available, but the 2 GB for $25 plan has been replaced by a pair of plans that cost $30 for 3 GB and $50 for 5 GB. The 2 GB plan remains available only for those currently using and automatically renewing at that level.

iPad subscribers who have postpaid accounts, where they are billed each month in advance for service, may pay $10 per GB for overages and be billed in a subsequent month. Those with prepaid service, in which all fees are paid in advance and fixed, may start a new 250 MB, 3 GB, or 5 GB plan when they have exhausted the usage allotment before a 30-day cycle is up.

New Take Control Book Unveils the Magic of Screen Sharing

Sharing screens is fun: it feels almost magical to view the screen of one Mac from another, and even more so to control another Mac from your own. With “Take Control of Screen Sharing in Lion,” Glenn Fleishman explains the many ways you can pull that rabbit out of your Mac’s hat. The 103-page ebook is available today for $10.

While fun to show off to less-experienced friends, screen sharing is an essential tool if you need to provide remote tech support (no more asking repeatedly, “So what did the dialog say?”), configure and manage remote servers, or collaborate on a document in real time, passing control of the cursor back and forth as necessary. That’s why Apple has provided a bunch of ways to share screens, including iChat, Back to My Mac, and the Screen Sharing application. Nor is Apple alone: Skype also provides Mac screen sharing, as do several iOS apps (yes, you can drive your Mac from your iPad, or even your iPhone!).

Glenn helps you choose the right screen-sharing technique for various situations, covering the pros and cons and what kind of security each method offers. He also discusses how to share screens with older Macs running 10.5 Leopard and 10.6 Snow Leopard, and how to manage your Mac from an iOS device.

Among the tricks and techniques the ebook covers are how to:

- Set up your Mac so that it can be controlled from your iPhone.

- Use screen sharing to help your confused uncle with his Mac.

- Find and launch the built-in Screen Sharing application on your Mac.

- Control an unattended Mac over the Internet.

- Turn on Back to My Mac with MobileMe or iCloud.

- Get set up and begin to share your screen through Skype.

- Give a presentation to a remote location through iChat Theater.

- Wake up a remote Mac in order to control it through screen sharing.

- Copy text from one computer to another while sharing screens.

- Put a shared screen in its own full-screen display in Lion.

- Control a far-away Mac through screen sharing when another user is logged in to that same Mac with a different account.

As the number of Macs in our extended professional and social networks continues to grow, so too does the need to access them quickly and efficiently from different locations. Glenn Fleishman’s “Take Control of Screen Sharing in Lion” puts the magic of screen sharing at your fingertips.

Apple Goes Back to School with iBooks 2, iBooks Author, and iTunes U

In a special event in New York City, Apple’s Senior Vice President of Worldwide Marketing Phil Schiller and VP for Productivity Software Roger Rosner unveiled a pair of free apps aimed at reinventing the textbook market: iBooks 2 and iBooks Author for the Mac. Not content to stop there, Senior VP of Internet Software and Services Eddy Cue and VP of iTunes Jeff Robbin then introduced the free iTunes U app for iOS.

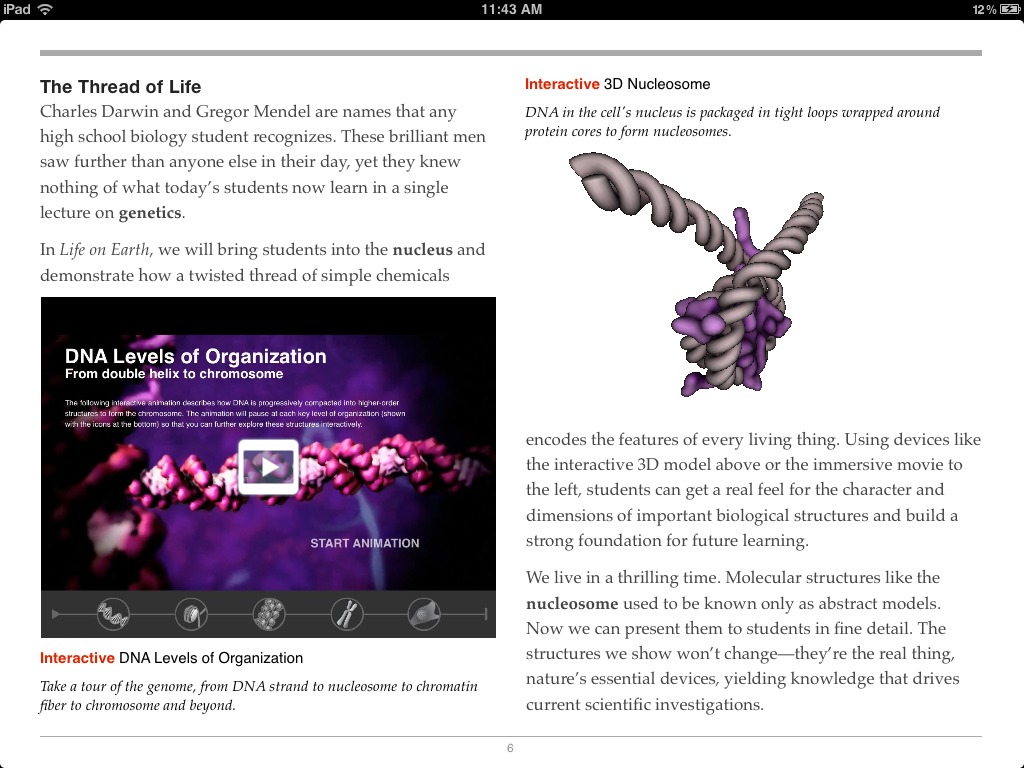

iBooks 2 — iBooks 2 is an update to Apple’s free ebook reading app for the iPad, enabling users to read specially created enhanced ebooks containing rich multimedia elements and interactivity, along with gorgeous layouts. Apple is focusing the new capabilities of iBooks on the textbook world, where videos, interactive images, 3-D graphics, and embedded review questions can significantly enhance the learning experience.

These features enable zooming into the image of a chromosome to get a better look, for instance, or rotating a 3-D model of a molecule. Or, an interactive graphic might enable you to tap the parts of an insect’s body, highlighting them in other photos elsewhere on the screen. Switching orientations changes the display from a scrolling approach (portrait) to a page-based design (landscape) with multiple columns and in-text graphics.

The iBooks textbooks that Apple showed off included a built-in glossary; you can browse through it or tap bolded words to look up their definitions in the glossary (which can even include images) or in a dictionary. Searching remains, of course, and is improved — when you tap a word, you can search for it in the textbook, in both text and media (presumably mediated by a search index), or extend the search to Wikipedia or the Web. If the textbook’s glossary includes the word, the glossary entry will also come up as a search

result.

Another nut that Apple has apparently cracked is that of pagination — it’s important in a class for everyone to be literally on the same page, and these books have fixed pagination in landscape mode. You can’t change fonts or sizes in landscape mode, but those standard iBooks controls appear once again in portrait mode.

More interesting are iBooks 2’s new note-reviewing capabilities, which work only in iBooks textbooks. Just as with iBooks previously, you can tap and hold or swipe to highlight text, and then tap the highlighted text to add a note. But with an iBooks textbook, notes can be used in a study card format where you see the highlighted text on the “front” of a virtual index card and your note on the “back,” which you reach by tapping it. The stack of cards can even be shuffled to aid in studying for tests.

Although iBooks 2 remains a universal app that runs on all iOS devices, the iPhone and iPod touch versions cannot display these new iBooks textbooks (they don’t even appear, which is good, since they’re huge). Plus, several times when I tried to view the “Life on Earth” textbook in iBooks 2 on my original iPad, all I got was the introductory audio on a gray screen — I had to shut my iPad down and restart it before iBooks 2 would show the book properly. (“Life on Earth”

is currently available for free; it’s a nearly 1 GB download.)

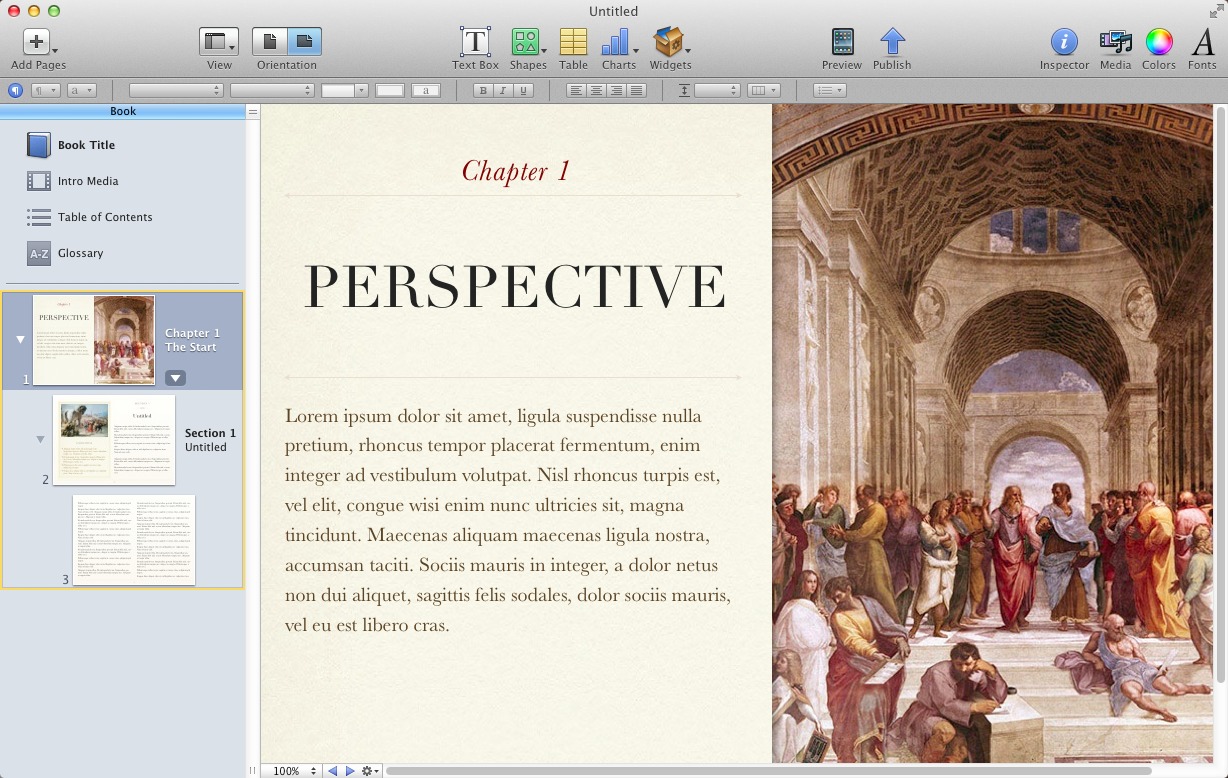

iBooks Author — Previously, iBooks was relatively limited in what it could display, and adding audio and video to an EPUB was difficult at best. Creating iBooks textbooks is where the second new app — iBooks Author — comes in. It’s a Mac application, available for free from the Mac App Store as a 136 MB download, and compatible only with Mac OS X 10.7 Lion. (It turns out that iBooks Author can be run in 10.6 Snow Leopard, but doing so requires some trickery. Digital Tweaker has the details.)

Not surprisingly, iBooks Author is reminiscent of Apple’s iWork applications, providing a number of templates to start. As in Keynote, you add pages to your book, putting text, graphics, and multimedia elements on each. You can import text from Pages or Word, and iBooks Author honors a set of styles for creating items such as headings, sections, and so on. You can even import Keynote presentations as interactive elements.

Like Pages, iBooks Author can build the table of contents automatically, based on styles that you use for headings in the manuscript, and you can create glossary entries from the Glossary toolbar or by Control-clicking a term and choosing from the contextual menu. Then you bounce over to the Glossary interface to enter a definition.

Unfortunately, iBooks Author doesn’t appear to have the change tracking and commenting tools that are necessary in any professional publishing situation, which means that text will have be pretty much final when it is flowed into iBooks Author, and any collaboration on layout and object placement will have to be done manually.

iBooks Author can export three types of files: text, PDF, and iBooks. The text export is likely good only for extracting text from an existing file, the PDF export appears to be useful only for a certain level of proofing, and the iBooks format is apparently slightly mangled EPUB, with a different MIME type (drop one on BBEdit if you want to look inside). You can export directly to a connected iPad for testing, which is far easier than the normal convoluted process for syncing ebooks to the iPad.

However, don’t get your hopes up for being able to use iBooks Author for EPUB in general — the license agreement states that files created with iBooks Author must either be made available for free or sold only through the iBookstore, and they will likely display only in iBooks on the iPad without some hacking. In short, if TidBITS wanted to create an enhanced Take Control ebook using iBooks Author, the only way for readers to purchase it would be through the iBookstore, which makes it much harder for us to communicate with readers and provide outside-the-book features as we do now. It would also make it harder for us to provide a similar ebook in other formats, such as one that can be read directly on the Mac or on the Kindle. I’m

not saying we won’t try iBooks Author, but it won’t be a sea change for our publishing model.

iTunes U — Apple’s third app — which requires iOS 5 and is available for not only the iPad but also the iPhone and iPod touch — does for online course content what iBooks 2 does for textbooks. Apple has long provided lectures from numerous colleges and universities in audio and video format via iTunes U, and with over 700 million downloads, it has been successful. The iTunes U app can play the simple audio and video for existing courses, but it gets far more interesting when used with a newly enhanced course (it also gets flakier — as with iBooks 2, I experienced a number of crashes; you can

expect minor updates to both apps as Apple works out the bugs). If you want a sample, check out Duke’s Core Concepts in Chemistry.

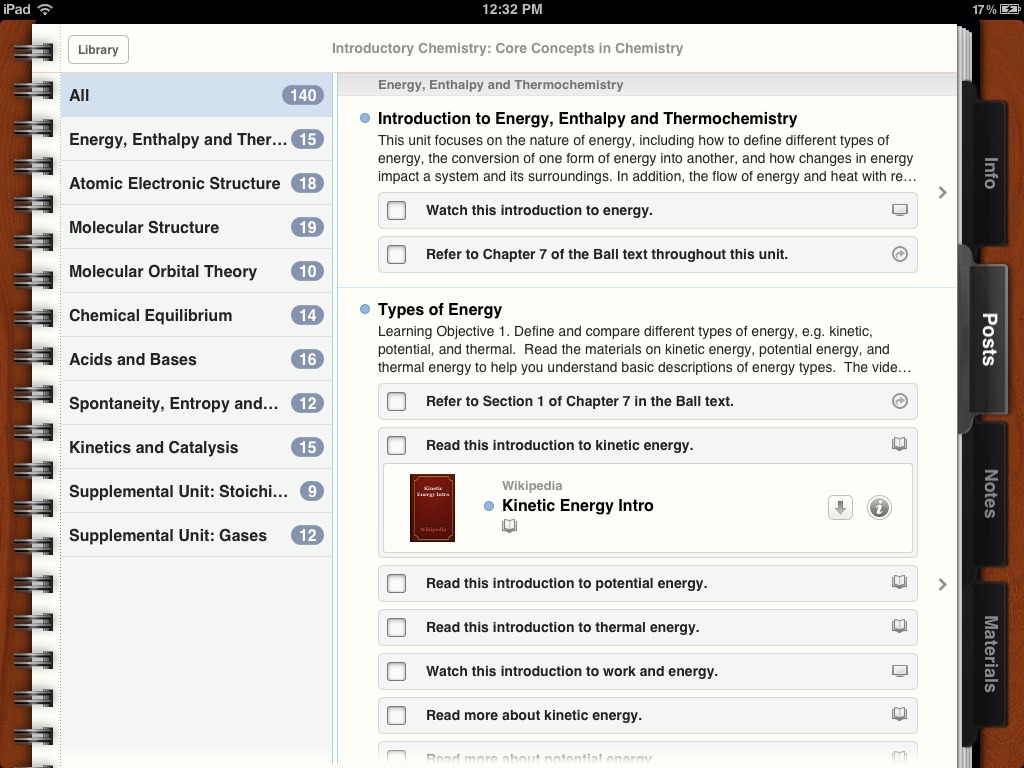

The iTunes U app breaks an enhanced course into four sections: Info, Posts, Notes, and Materials, and you switch between them using tabs on the right side of the screen (iPad) or bottom of the screen (iPhone/iPod touch). The Info tab provides subsections for things like a course overview, an instructor bio, and the outline of the course.

The heart of the course lies in the Posts tab, which brings together text, audio, and video lectures and assignments, along with the new iBooks textbooks created with iBooks Author (which can be read only on an iPad, remember). Although the Core Concepts in Chemistry course I looked at seemed fully fleshed out, for courses that are in progress, new posts alert you to their presence via notifications. You can even play an audio or video lecture and listen in the background while in a different part of the interface, such as the

Notes tab. When you complete an assignment, you can check it off.

In the Notes tab, you can create general course-level notes, and any notes from iBooks that are part of the class will appear as well. (But remember, you can make notes only on EPUB-based ebooks; although iBooks can display PDFs, which will be common in courses, you can’t make notes on those.) Those books may appear within the assignments, and they’re all collected in the Materials tab as well. The course includes (or will download) all the core materials, but some supplemental materials, including books and apps, may require

additional purchases.

How one creates an iTunes U course was not shared, although Apple said that six schools have had access to the new tools and have created over 100 new online courses. We’d like to see Apple open up the tools necessary to create an iTunes U course, just like iBooks Author, such that it would be possible to create — and sell — training courses via iTunes, although that gets back into the single-store debate.

Ironically, the presence of all this information online may reduce attendance in classes even further, something we’ve heard professors in iTunes U lectures complain about with the ready availability of recorded lectures.

A more speculative question is what will happen — particularly in certain subjects where collaborative scenarios or access to specialized equipment aren’t important — to higher education in general if it becomes possible to take most courses online in this fashion. Will the intangibles of a college education — maturation, networking, exposure to opportunities — and the eventual diploma be seen as worth the skyrocketing tuition costs?

An Apple a Day for Education — I’ll give Apple this — they don’t think small. These apps set a new bar for electronic books and online courses, and the apps are all available for free. The problem is that Apple also wants to own the entire pie, and in the process say exactly what is and is not possible. That’s not particularly different from Amazon, which tries to lock works into the Kindle ecosystem by refusing to support EPUB. But at least the far-less-ambitious Kindle format can be converted to from other formats.

Debates are already raging on Twitter about how iBooks Author doesn’t allow works created with it to be sold anywhere but the iBookstore, and we publisher types are already trying to imagine how we can justify the extra effort and expense of creating iBooks textbooks for a single retail outlet. Plus, Apple is talking about these textbooks being inexpensive — on the order of $14.99 — which may play havoc with publisher business models that rely on high prices for books that are reused for multiple years. How it will shake out in the publishing world remains to be seen.

On the other side of the equation are the schools — where will the budget come from to outfit students with iPads and to buy these iBooks textbooks? It’s not impossible — we know of some local school districts that have had great success with pilot programs for tablets (Android, in this case), both in terms of student achievement and cost savings. But many schools can purchase only state- or district-approved textbooks, and that’s where Apple’s connection with publishers may be key — it should be much easier for a government entity to approve an electronic textbook if it is simply the electronic version of an approved traditional textbook.

Why iBooks Author is a Big Deal

When Apple made its education announcements last week (see “Apple Goes Back to School with iBooks 2, iBooks Author, and iTunes U,” 19 January 2012), the Web reverberated almost instantly with a deafening clamor of commentary and criticism. For some people, Apple’s end-user license agreement (EULA) for its iBooks Author program was a show-stopper, as well as providing corroborating evidence for the theory that Apple was as mendacious and evil as many had feared all along. For others, it was the new iBooks multi-touch book file format, which was seen as a direct attack against ebook standards and a betrayal of Apple’s commitment to open standards. And for still others, including our own Glenn Fleishman, it was Apple’s marketing message itself that evoked frustration and disappointment.

Although much of the criticism of Apple and iBooks Author is deserved, I don’t care. Here’s why.

First, I think that the EULA, like iBooks Author itself, is version 1.0, and that it will change — Apple has changed EULAs before, notably with its iOS restriction against which development tools were used to create apps. Second, I think the file-format issue is something of a red herring: iBooks 2 still displays normal EPUBs just fine, and will likely support the EPUB 3.0 standard sooner or later.

Third, although, like Glenn, I have heard the “students are bored and software will fix it” pedagogical panacea claims all before, and probably, I think, heard much more of it than Glenn: So what? It was ever thus.

I spent more than a quarter of a century in the thick of educational software development and interactive multimedia production, under the aegis of both educational institutions and publishing companies. Most of those for whom I developed such materials claimed the same magical pedagogical powers for the stuff on which I worked that Apple claimed for iBooks Author last week. Then, as now, it was over-reaching marketing nonsense. But most marketing is just that: over-reaching nonsense.

Teaching is hard. It was hard in a one-room schoolroom with slate-toting students and it is hard in a modern, media-rich classroom filled with digital tablet-bearing students. Furthermore, bad teachers are bad teachers no matter what tools they have available, and good teachers are good teachers, whether armed with chalk or laser pointers. Creating curricula that work effectively with disparate assemblages of young humans of various backgrounds, home environments, and states of cognitive development is enormously difficult, no matter the media used to deliver the curricular materials.

And it always will be.

But here’s the thing: having access to good instructional resources is always better for students and for teachers than not having such access. And although interactive multimedia textbooks of the type that iBooks Author makes so very easy to prepare probably won’t make a bad teacher into a good one or a poor student into a candidate for valedictorian, it is much better to have them available for teachers and for students than not.

Availability was the big stumbling block that tripped up most of the instructional projects I worked on since the early 1980s. At the beginning of my instructional technology odyssey, computers in classrooms were very rare, and teacher familiarity with digital technology all but non-existent. Back then, one really had to do a Bolshoi-scale song-and-dance just to get even small instructional technology pilot programs established.

Later, the biggest availability issue lay not in convincing the Powers That Be that interactive media had a place in education, but in finding the financial resources to build the necessary computer labs. And, just as costly — if not more so — was finding and hiring the people to develop the materials for those labs: the development tools were difficult to use, expensive, and hard to come by, and those individuals who had both the pedagogical and the technological knowledge to employ those tools effectively were just as expensive and hard to find.

Today, however, low-cost digital media tablets herald the end of the expensive dedicated computer lab. Sure, a $500 iPad is not cheap, but it’s far cheaper and far more within the reach of parents and schools than the bolted-down lab machines of years gone by. At the same time, though, cost and difficulty of developing rich instructional materials for these new devices has not seen a similarly drastic decline.

Until iBooks Author. Here is a tool that most teachers who are capable of writing an email can master. Here is a tool that produces something that is enough like a book that even a teacher with no training in computer-based pedagogy can understand and see how to use for teaching. Here is a tool that can deliver certain instructional experiences that are just much harder to deliver from a paper book, even when mediated by a teacher of exceptional skill.

No, I don’t expect that iBooks Author will be the One True Magic Bullet that will slay all the pedagogical woes of the world or even most of them. Nor do I see it being even the one true instructional material development application for the ebook generation.

What I do see, however, is that iBooks Author and Apple’s related educational initiatives have a real chance of finally tearing down the availability stumbling blocks.

I think that’s a good thing.

iBooks Textbooks: Not Exactly Innovation in Education

No iPhone 5, no iPad 3, no update to the Mac Pro range, at Thursday’s Apple education event in New York. No, the innovations Apple were unwrapping at the Guggenheim were altogether more surprising.

Claiming to “re-invent the textbook,” Phil Schiller, Apple’s senior vice president for Worldwide Marketing, portrayed Apple as a crusader for educational innovation, and announced a new product range that, according to one of the talking-head teachers roped in to shill for iBooks textbooks, would “change my students’ lives for the better.”

This was intended to be, clearly, a spectacular advance, a leap forward in educational technology that would disrupt, innovate, surprise, delight; certainly, for me, a technology commentator, and a teacher since 1991, this should have been a revolutionary innovation. But it didn’t, and it wasn’t.

A company such as Apple should, surely, have the potential not simply to embellish and enhance the textbook as it exists in its current paradigm; they should have it in them, especially if they are to have the hubris to claim that they are “reinventing” the textbook, to introduce something utterly radical, something that turns the current understanding of the textbook utterly on its head.

Instead, Apple’s presentation should have been fronted by Rod Serling. I was watching the thing on a fast, powerful, modern laptop computer — an Apple MacBook Pro with a quad-core Intel processor, accessing fast Internet over a wireless connection, and downloading the new product as it was announced onto an Apple iPad — a tablet computer! — at the same time. And yet, and yet… what was being shown off, what was touted as a reinvention of the textbook, belonged back in the mid 1990s.

An iBooks textbook, we were promised, would be interactive. Interactivity in content has been a fundamental aspect of computer-aided delivery for as long as we’ve had CD-ROMs — I updated my Mac IIsi to a IIvx back in 1995 because I really wanted the CD-ROM drive, and immediately started playing with multimedia titles that were starting to appear. And what made these titles attractive was the fact that they could build on simple static text, offering, as it was known then, a multimedia experience — video, animation, audio.

This was, as I say, seventeen years ago — around the time some of the target audience of the iBooks textbooks were born. In those seventeen years, computer-mediated instructional materials (“textbook” is such an old-fashioned word) should, surely, have moved on. But what I find on my iPad today, in 2012 (for, at least, as long as iBooks 2 is usable; my experience so far is that it’s as unstable as a hippo on rollerskates) is an experience that, other than being on my ever-so-modern tablet computer, is, essentially, the same as that offered by multimedia CD-ROMs back in the early 90s.

It is true that iBooks textbooks offer a level of engagement that paper books are unable to match, and there is definitely evidence to suggest that novelty in presentation, especially when that novelty involves computers, will, at least temporarily, reduce affective barriers to learning. I know — I did some of the research as a graduate student, again back in the mid-1990s. But those years also saw an incipient movement to take the possibilities offered by computers to personalise and individualise the learning experience offered by technology and exploit the platforms available even fifteen years ago.

At a language-teaching conference in Japan in, I believe, 1999 or 2000, I listened to a presentation on adaptive language testing, a system that tested, observed student performance, and then selected the next instruction-testing sequence based on that performance. While this was, at that point, a somewhat rudimentary application of the principles involved, it at least showed that computers were able to make decisions on what to do next based on what had preceded that decision. iBooks 2 offers no such flexibility, as far as I can tell so far.

Partly this is due to the fact that iBooks textbooks are a product of iBooks Author, itself essentially the love child of iWork’s Pages and Keynote. Absent, so far, are any programming tools, even simple ones, that can allow any form of data-storing scripting, which is a shame, since programs such as FileMaker Pro, SuperCard, even HyperCard (of sainted memory) allow solutions to be created that offer a degree of decision-based scripting. Had Apple incorporated such elements into iBooks Author, a whole new level of interactivity and personalised learning could have been generated: “Steve, I see you’re spending a lot of time on simple harmonic motion, but you’re not doing very well on the end-of-topic quiz. Would you like some

extra help with this topic?” But while the student can interact with the content, the content remains unable to interact with the student, and this seems to be an opportunity badly missed; I can only hope that scripting will feature strongly in a future version of iBooks Author.

As it stands, iBooks textbooks offers very little that hasn’t been on offer for nearly twenty years. Far from reinventing the textbook, Apple have simply taken an existing concept and applied it to a new medium, with, it appears, relatively little in the way of points of difference due to the particular nature of the iPad platform. And so, instead of static text and static images on a page, we are now presented with static text and some moving images on a page. This is a small step forward in terms of paper textbooks, but, in terms of the state of the art with regard to multimedia presentation, it is, absent scripting, possibly even a retrograde step.

In terms of the pedagogy, too, advances are lacking. Beginning with Gardner’s work on multiple intelligences back in the 1980s, educational theory has emphasised learning modalities; it is impossible to escape a teacher-training programme in, at the very least, the United States or New Zealand, without having the concept of visual, auditory, kinesthetic, and tactile learners pounded deep into one’s brain; it is equally impossible to survive a lesson observation without some questioning of how much a teacher has addressed all of his students’ learning styles.

Textbooks, of course, by their very nature are limited to the visual modality; that is an inescapable constraint of paper. But this constraint, by and large, remains intact in an iBooks textbook, even though the technology no longer imposes it. The essence of an iBooks textbook is written text — everything else is an adjunct to that written text.

Being a physics teacher, I naturally downloaded a sample of McGraw Hill’s physics textbook, and played with the chapters on waves and vibration. This has never been the easiest topic in the world to teach in the classroom; springs, ropes and waveform generators can be rather temperamental, and while on a good day a standing wave can be fun, I’ve yet to see a teacher actually manage a third harmonic in a rope on demand. This is where the potential of iBooks 2 is teased to teachers, but even then not entirely brilliantly implemented, and this is a function of the file-size limitation set by Apple.

iBooks textbooks, we have been told, can be up to 2 GB in size if they are to be distributed through the iBookstore. This is reasonable — Apple is hoping to sell a lot of these books, of course, and so they need to make sure that their datacentres, already serving up iTunes, iCloud, and two App Stores, don’t suddenly start laboring under 15 GB behemoths. (This limitation, though, appears not to apply, for example, to the 2.77 GB of biology currently on offer from Pearson.)

I would like to see every photograph in my physics textbook link to a video of a dynamic experiment. But while videos of projectiles, and animations of graphs of their motion, would be a valuable enhancement to a textbook, their creation will inevitably increase production costs for the book, and slow down the editorial cycle somewhat. I already use YouTube to demonstrate things I can’t readily demonstrate in the classroom, such as the brick-on-a-rope-not-hitting-your-face illustration of conservation of energy, but I spend a lot of time doing quality control on YouTube videos; having a ready-made bundle of content on an iPad would be enormously beneficial. Similarly, trying to draw, on a flat, two-dimensional whiteboard, a diagram of

the three-dimensional vectors of Maxwell’s Laws is guaranteed to give headaches — so much easier simply to call up the relevant page on an iPad. But the more content you include in your book, the bigger the file will be, and the longer it will take to download.

And downloading is an issue for many people. As I have written about in “Paying by the Bit: Internet Access in New Zealand” (15 January 2010), outside the United States not everyone, including schools, has access to unlimited Internet connections. If my students were issued iPads next month, for the start of the new school year, they would then need to download their textbooks. Would they do this at home? Given that a typical home Internet connection in New Zealand, assuming it even has broadband (dialup is still quite widespread here), has a data cap of 5–10 GB per month, it’s fair to assume that most of my students will want to download their books at school. Perhaps the school

would download one instance of each book, and syncing could happen centrally; this would, of course, require that all students sync their iPads with the school’s computers, of which there are not that many; the headaches are multi-layered. Or my school would have to set up and maintain a Wi-FI network for this purpose; that simply becomes another associated expense.

This is before the school has even provided the iPads. Given the uproar over plans by Orewa College, a moderately well-off secondary school north of Auckland, to require that all incoming students buy iPads or similar, I very much doubt that my school, in the poorer end of south Auckland, would fare terribly well in requiring that parents purchase. This would then leave the school having to buy the devices themselves, which would be difficult. My school, with its socio-economic decile rating of 2, receives almost no funding from the “voluntary” contributions that other schools raise from parents. As a result, it is dependent almost

solely on its operating budget of around $1,000 per student from the Ministry of Education. Given that iPads start at $799 here in New Zealand, a very generous educational bulk-purchase discount from Apple would be required in order to make this an even remotely feasible purchase.

In American schools, too, where budget crunches are hurting badly, I question how many schools will be able to afford this technology. Pinellas County in Florida, where I once taught, is facing a budget crisis such that teacher layoffs and furloughs are being proposed to try to make the books balance. Last year’s budget allowed for a per-student spend of $7,845; a $499 iPad would represent 6 percent of the entire funding allocation for each of the 103,000 students in the county. But while the per-student budget

in Pinellas may seem significantly more generous than a New Zealand school’s funding, remember that out of that money must come teacher salaries, which make up 85 percent of the district’s budget; of the remaining $1,177, a $499 iPad is still a very big ask, and when teachers’ salaries are being considered fair game for budget reduction cuts, a five-million-dollar expenditure on iPads would not sit well.

So, in the end, is it worth it? Will students benefit from iPads with textbooks on them? Will they, indeed, benefit sufficiently to warrant the funds outlays involved? Yes, paper textbooks are expensive, and yes, they involve a buy-in that locks schools into using them for maybe five years. But, in physics, for example, the content being taught is not changing so rapidly that we need to replace our textbooks that often, even if wear and tear make it advisable. We can make do for another year; lock-in is not as terrible as it might seem.

But while iPads make it easy and relatively affordable to update content readily, how often will publishers offer free updates? By the time a publisher has updated a textbook to the extent that it actually exploits iBooks 2 and the iPad fully, will that then be a free update? In the meantime, the hardware costs of iPads is not one-off; once the up-front purchase has been made, there will be service costs. Do schools buy AppleCare? What happens to out-of-warranty repairs, in particular batteries wearing out? Will school insurance cover accidental loss, damage, theft?

Had iBooks 2 and iBooks Author been released back in 1996, when CD-ROMs were still a pretty neat idea, I would be writing a very different article. But today, when Apple are trying to claim that twenty-year-old ideas represent a “reinvention” of the textbook, I am less impressed. Schiller, see me after school. Grade: C-. Really must try harder.

[Steve McCabe is a Mac consultant, tech writer, and physics teacher in New Zealand. He writes about his adventures in New Zealand, he blogs about technology, and he has just finished rebuilding his personal Web site.]

Examining iBooks Author from the Publisher Perspective

Apple’s announcement last week of iBooks 2 and the iBooks multi-touch textbooks, which are created in the free iBooks Author app on the Mac, has generated admiration and applause simultaneous with consternation and criticism. That has been true even within our ranks.

Glenn Fleishman wrote an editorial for Macworld in which he points out that technology initiatives in education have largely fallen flat over time and that iBooks textbooks don’t seem to offer much that’s new. Steve McCabe, a New Zealand physics teacher and occasional TidBITS contributor weighs in on Glenn’s side, arguing that iBooks Author merely warms up twenty-year-old ideas in “iBooks Textbooks: Not Exactly Innovation in Education” (22 January 2012). On the other side, Michael Cohen, who has worked in both educational software development and interactive

multimedia production, believes that having good instructional resources is always better than not having them (see “Why iBooks Author is a Big Deal,” 21 January 2012).

I’d like to look at a different aspect of the entire scenario — what these announcements mean for publishing in general — and to do so from the perspective of a publisher who would dearly love to have better publishing and reading tools.

The main problem with iBooks Author is its license agreement, though it may take some work to find it. When you export something you’ve created in iBooks Author to the iBooks format, you’re greeted with a dialog that tells you “Books can only be sold through the iBookstore. To publish your book on the iBookstore choose File > Publish.” Ignoring the poor placement of the word “only,” which should follow “sold” to make the sentence mean what Apple wants it to mean, the dialog also includes a link that explains more about publishing to the iBookstore. That explanation page in iBooks Author’s help says:

Even if you don’t submit your book to the iBookstore, you can still export a book that you can distribute yourself.

Important: If you choose to distribute your book yourself, be sure to review the guidelines in the iBooks Author software license agreement. To see the agreement, choose iBooks Author > About iBooks Author, and click License Agreement.

And when you finally get to the PDF-based license agreement, you’ll find this preamble and explanatory clause.

IMPORTANT NOTE: If you charge a fee for any book or other work you generate using this software (a “Work”), you may only sell or distribute such Work through Apple (e.g., through the iBookstore) and such distribution will be subject to a separate agreement with Apple.

2B. Distribution of your Work. As a condition of this License and provided you are in compliance with its terms, your Work may be distributed as follows: (i) if your Work is provided for free (at no charge), you may distribute the Work by any available means; (ii) if your Work is provided for a fee (including as part of any subscription-based product or service), you may only distribute the Work through Apple and such distribution is subject to the following limitations and conditions: (a) you will be required to enter into a separate written agreement with Apple (or an Apple affiliate or subsidiary) before any commercial distribution of your Work may take place; and (b) Apple may determine for any reason and in its sole discretion

not to select your Work for distribution.Apple will not be responsible for any costs, expenses, damages, losses (including without limitation lost business opportunities or lost profits) or other liabilities you may incur as a result of your use of this Apple Software, including without limitation the fact that your Work may not be selected for distribution by Apple.

I wanted to include the full path to getting the agreement, and all the license text in question, to eliminate any concern that my summary here is in any way inaccurate. In essence, Apple is saying, “You can distribute anything you create with iBooks Author for free in any way you want; if you want to sell what you create (or include it as part of a subscription service), you may sell it only through Apple, and even then only if Apple approves it.”

Realizing this immediately raised my publisher hackles. “But, but, but,” I spluttered, “there’s no way in hell I’m going to publish something that I can sell only in the iBookstore, and even then only if Apple approves it. There aren’t even any guidelines outlining what Apple will and will not approve!”

And you know, for the most part, I haven’t changed my mind. I think this license agreement is attempting to do something that’s very seldom, if ever, been done with consumer-level software before (apparently, some software development kits have similar clauses), and based on my experience with selling through the iBookstore, I would strongly discourage any non-textbook publisher from basing a significant business decision on iBooks textbooks. Although it’s likely that some early titles will sell well because of the novelty value, the iBookstore doesn’t yet have a sufficiently large customer base, and it would be nuts for such a publisher to bet the farm on a single retailer, especially one that reserves the right to reject your

books. (For the record, although the trend is moving upward, the iBookstore made up roughly 4 percent of Take Control sales in 2011 — certainly welcome, but not a number we could use to justify a major change in business model.)

I don’t want to get further into criticism of the iBooks Author license agreement, not because I think it is a good thing, but because Dan Wineman has done so well in a pair of posts: “The Unprecedented Audacity of the iBooks Author EULA” and “Common Misconceptions about What I Wrote Yesterday.” I also don’t want to criticize the iBooks Author license agreement further because I’ve realized that we’re missing Apple’s point. (We may not agree with it once we see it, but it’s important to acknowledge it first.)

The trick is to remember that Apple seldom explains any of the rationale behind its decisions. The famous public letters from Steve Jobs were the main exceptions, and those came only when a sufficient fuss was made that Apple decided to drop the curtain. So all we can do is read into the tea leaves of Apple’s actions and public statements. What we cannot do is read anything into Apple’s inaction or silence on a particular topic — and that’s just what we’ve been doing.

The fact of the matter is that last week’s event was explicitly targeted at education, and to be more clear, at the education market, which is separate from the concept of educating people in general. While we consider our Take Control ebooks to be educational — they certainly attempt to impart knowledge and teach skills — we are by no means part of the education market. The mistake we — and so many others — have made is to assume that iBooks Author is aimed at anyone other than textbook publishers and teachers. It just isn’t.

Although I’m not an expert in the textbook publishing world, I do know that it’s quite different from the technical book publishing world. In particular, where we sell copies of our books to individuals, one at a time, textbook publishers in K-12 markets in the United States sell in bulk to schools, or even entire school districts, and textbooks need to be approved to qualify for state financial assistance, so that a school can purchase them with state-provided funds. (I suspect college textbooks are more on a class-by-class basis.)

So in a situation where every student already needs an iPad to read an iBooks textbook, textbook publishers aren’t going to be at all bothered by the restriction of selling only through Apple (and it will be done through Apple’s Volume Purchase Program anyway). It’s possible that having Apple involved in these volume buys might be a benefit to the textbook publishers, since they won’t have to fuss with the technical details of counting seats and the like.

Another aspect of the textbook publishing world that’s quite different from many other types of publishing is that textbooks, while not entirely evergreen, tend not to need constant updates. That’s due in large part to the fact that what’s taught in 7th grade science, for instance, isn’t going to change much based on new discoveries, and to the extent that other subjects might, teachers are accustomed to supplementing textbooks with other resources. Textbooks have to last at least a few years in paper, so the content has to be stable. So textbook publishers can devote more time and energy to creating multimedia and interactive resources that would be hard to justify in a field where the book might have only a 6- to 24-month

lifespan before becoming painfully out of date.

In fact, textbook publishers may not have to create much new content. Many paper textbooks already have Web-based adjuncts, and I would assume (since it’s what I would do if I were in charge) that textbook publishers will be repurposing that online content when possible rather than incurring new development costs. For publishers in markets like ours, the multimedia and interactivity development costs would be entirely new and could be quite high, making the business proposition of a $14.99 book (less Apple’s 30 percent) rather tenuous. Especially for books with short shelf lives.

What about individuals? Teachers are a dedicated lot, and I believe we’ll see teachers — and other people, to be fair — creating quite a number of iBooks textbooks to give away for free, just because they want to share their knowledge and think that iBooks Author is a cool tool to play with. This isn’t new — when I was a Cornell undergraduate, I was on the receiving end of a textbook (in Greek Composition, nonetheless!) written by Matt Neuburg for a class of two students, simply because none of the existing books explained the subject the way he felt it should be explained. This is a good thing, and exactly why Michael Cohen thinks iBooks Author will be a big deal.

But I don’t see the iBooks platform becoming a significant self-publishing tool for commercial books as it stands right now. It’s not so much that the iBookstore is too limiting as a single sales venue — self-published authors aren’t likely to be as concerned about multiple sales outlets as an established publishing house would be — but that the iBookstore isn’t easy enough for an individual author with just a title or two. Despite how iBooks Author points people to publishing through the iBookstore, it’s highly non-trivial to work with the iBookstore, and internally, the iBookstore itself points those intimidated by the technical and business requirements to Apple-approved aggregators such as Ingram, INscribe Digital, LibreDigital, Lulu, and Smashwords in North America, and Bookwire and Immatérial in Europe.

There’s one other key thing to keep in mind about how Apple is focusing all this on the education market, and that’s that iBooks textbooks can be viewed only on the iPad. As technical limitations go, this one is a bit weak — the files are only slightly customized EPUBs inside a different wrapper — but the fact remains that E-Ink-based Kindles could never imagine displaying these files, and while Android-based tablets (including the Kindle Fire) might have the display and processing chops to do so in theory, there’s no software that can show them right now. Macs and Windows-based PCs are also right out at the moment.

This all makes huge sense from Apple’s perspective — you create a scenario where content can be created only on a Mac, purchased only from the iBookstore, and viewed only on an iPad. What’s not to like? If you’re not a textbook publisher, though, you might not want to create your content on a Mac, you definitely don’t want to sell only through the iBookstore, and you don’t want to restrict your audience to iPad owners. That’s what’s not to like, and the people I know at Apple undoubtedly realize that — they’re not stupid. But again, refocus the entire initiative on the education market, and those criticisms largely fall away. Even better, the textbook market is dominated by a few large companies that Apple can

negotiate with directly — Pearson, McGraw Hill, and Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Note that I’m not saying that I like things the way Apple has set them up. What I would like to see instead is Apple competing entirely on quality instead of platform lock-in: the quality of iBooks Author and the Mac for creating content, the quality of the iBookstore as a retail experience, the quality of the iPad as the hardware platform, and the quality of iBooks for reading. All that’s necessary for Apple to make that change is to switch to standard EPUB 3.0 for the iBooks Author output format and drop the iBooks Author license agreement. Apple has proven that it can compete well on quality — look at the iPod and the iTunes Music Store, and at the iPhone and iPad and the App Store. So when I see Apple taking a different tack

and competing based on platform lock-in, I start wondering if Apple lacks confidence in the quality of the products in question.

(For what it’s worth, I don’t buy the argument that the output of iBooks Author is akin to an app — there’s a big difference between iOS-specific code and slightly mangled EPUB when it comes to platform lock-in. With iOS apps, Apple’s lock-in is largely technical; with iBooks, it’s largely contractual.)

In a world where iBooks is an open publishing platform, publishers still face the hurdle of creating rich content that can’t be viewed on anything other than an iPad (the Kindle can’t display EPUB now, and I don’t see that changing), but they can do so without fear of being rejected from or locked into the iBookstore.

We can hold out some hope that Apple is thinking about publishers outside the education market who want to create iBooks that aren’t textbooks and won’t be sold in bulk to school districts. Apple has on occasion changed license agreement terms, most notably relaxing development tool restrictions for iOS apps. And some of the text surrounding iBooks Author goes beyond the education market. First, on the iBooks Author page on Apple’s site, there’s this description (emphasis mine):

Available free on the Mac App store, iBooks Author is an amazing new app that allows anyone to create beautiful Multi-Touch textbooks — and just about any other kind of book — for iPad.

And in the Mac App Store description of iBooks Author, there are a number of statements that make the app sound like a publishing tool for the rest of us:

Now anyone can create stunning iBooks textbooks, cookbooks, history books, picture books, and more for iPad. All you need is an idea and a Mac. Start with one of the Apple-designed templates that feature a wide variety of page layouts. Add your own text and images with drag-and-drop ease. Use Multi-Touch widgets to include interactive photo galleries, movies, Keynote presentations, 3D objects, and more. Preview your book on your iPad at any time. Then submit your finished work to the iBookstore with a few simple steps. And before you know it, you’re a published author.

It’s entirely possible this is just marketing fluffery, since the final bit about submitting to the iBookstore with a few simple steps is pure hogwash (all File > Publish in iBooks Author does is copy your book and its cover graphic into a new document in iTunes Producer, one of Apple’s most misbegotten programs ever). But it is a ray of hope that Apple plans to move beyond this current laser-like focus on the education market to open up the entire iBooks platform to the publishing world at large.

And that, I think, would be a good thing for everyone, including Apple.

TidBITS Watchlist: Notable Software Updates for 23 January 2012

iTunes 10.5.3 — In conjunction with the unveiling of interactive textbooks in iBooks 2 for the iPad (see “Apple Goes Back to School with iBooks 2, iBooks Author, and iTunes U,” 19 January 2012), Apple has released iTunes 10.5.3, whose only change is support for syncing these new titles between iTunes and an iPad running iBooks 2. (Free, 102 MB new download or 10.5 MB via Software Update)

Read/post comments about iTunes 10.5.3.

Typinator 5 — A major new release, Ergonis’s Typinator 5 typing expansion utility has been updated with a plethora of new features, the biggest of which is scripting support. Text expansions can now execute external scripts written in AppleScript, Perl, PHP, Python, Ruby, and other shell scripting languages, and then include those results in the expansion. Other new features include date and time calculations, a calculator in the Quick Search field, and the option to delete characters typed immediately before an abbreviation. The internal expansion mechanism has been redesigned with improved support for Undo and

handling of fast typing during expansion processing, and the update includes a variety of fixes to improve stability. (€24.99 new with a 25-percent discount for TidBITS members, free update for licenses purchased on or after 1 June 2011, 4.4 MB, release notes)

Read/post comments about Typinator 5.

QuarkXPress 9.2 — Quark has released QuarkXPress 9.2, a free update with new features focused on publishing ebooks and iPad apps. In addition to creating new projects for EPUB export, you can add audio and video to an EPUB ebook, specify types of content that should be included in the table of contents, and store export settings in an output style. On the iPad front, the update adds new Actions for controlling sound and video elements in iPad apps as well as Newsstand support under iOS 5. ($849 new, free update, 1 GB, release notes)

Read/post comments about QuarkXPress 9.2.

Default Folder X 4.4.8 — Contextual menus have returned to the latest update of St. Clair Software’s Default Folder X 4.4.8, making them available in all Open and Save dialogs and enabling you to rename, delete, get info, and compress any file. This release of the Open and Save dialog enhancement utility also brings compatibility with the latest version of Google Chrome, adds support for QuickTime Player X, improves the capability to ignore certain folders, and fixes a variety of bugs that caused Default Folder X to crash or hang. ($34.95 new with $10 off for TidBITS members, free update, 10.5 MB, release notes)

Read/post comments about Default Folder X 4.4.8.

ExtraBITS for 23 January 2012

Read on for a collection of links to the most interesting articles and resources that the TidBITS staff discovered on the Web this week.

New York Times Explains Chinese Advantage for Apple — The New York Times has a clever feature article explaining why Apple (and other firms) manufacture in China for a host of reasons, of which low wages may be a relatively small part. The ability to hire a massive number of trained people nearly instantly is one factor, regardless of how well those people are treated by the contractors Apple employs. For instance, Americans typically won’t live in dormitories and work six 12-hour days in a row, which is commonplace in China and other developing

nations.

Apple Textbooks Repeat the Past — Glenn Fleishman writes in an editorial at Macworld about how Apple’s “new” digital textbook plan reminds him of countless efforts to push multimedia pedagogy without evidence that it improves achievement in any measure. The iPad is remarkable, but interactive textbooks aren’t.

MacJury Deliberates about iBooks Author EULA — Just hours after Apple’s education announcements on 19 January 2012, the Internet began to vibrate with discussion, much of it dismayed, about some of the terms in the end-user license agreement (EULA) that accompanies Apple’s iBooks Author application. Take Control Books editor-in-chief Tonya Engst was empaneled with other concerned netizens by Chuck Joiner at MacJury to deliberate about how the EULA, even more than the iBooks format itself, might affect the publishing community.

Supreme Court Shrinks Public Domain — We haven’t been following the Golan case before the U.S. Supreme Court, but Techdirt explains how the Court has ruled that the United States can retroactively take works out of the public domain and put them back under copyright. The government’s claim is that this is necessary for a trade agreement to make other countries respect our copyright, but the end result is that it could (and likely will) be used to shrink the public domain. We’re all in favor of copyright

giving incentives to creators, but we can’t see how putting the works of dead people back under copyright will result in any new work.

Wikipedia Blackout Leaves Nagging Hole — David Carr of the New York Times neatly explains how Wikipedia’s blackout to protest poorly drafted anti-piracy bills under consideration in the U.S. Congress leaves a ragged hole in the Internet. He doesn’t see Wikipedia as authoritative, but as fundamental: it’s the way to start to understand and research millions of topics.