TidBITS#1155/07-Jan-2013

We’re back from our break, refreshed and ready to delve into whatever 2013 may bring. To get you started on the new year, we have a wide-ranging issue. Agen Schmitz leads off with brief coverage of the iOS 6.0.2 release for the iPhone 5 and iPad mini, and Adam Engst follows up with a warning about how some users are seeing unexpectedly poor battery life after updating to 6.0.2. Michael Cohen passes on the news that Google Sync will cease to be available for new devices later this month, Glenn Fleishman writes about the City of Seattle’s gigabit Internet plans, Jeff Carlson ponders the design-driven trend away from outsourcing manufacturing to China, and Rich Mogull examines Apple’s security efforts in 2012. Notable software releases over the past few weeks include Carbon Copy Cloner 3.5.2, Airfoil 4.7.5, SpamSieve 2.9.6, BusyCal 2.0.2, Typinator 5.4, and BBEdit 10.5.1.

iOS 6.0.2 Squashes Unspecified Wi-Fi Bug in iPhone 5 and iPad mini

Released with a typically perfunctory description, Apple has pushed out iOS 6.0.2 for the iPhone 5 and iPad mini to fix “a bug that could impact Wi-Fi.” With such a blank slate to divine from, it’s hard to know what problems iOS 6.0.2 might address. However, there’s a lengthy and vitriolic discussion thread (3,155 posts and 485,390 views) at Apple Support Communities that suggests this fix is meant to patch a problem with the iPhone 5 that gives the appearance of a connection to a Wi-Fi network while receiving no data over Wi-Fi. Unfortunately, another long thread (2,587 posts and 371,438 views) detailing Wi-Fi woes seems to point its finger at iOS 6 itself, given that the problem started at its release and occurs on numerous devices other than the iPhone 5 and iPad mini.

If you have workable Wi-Fi connectivity, we recommend going the over-the-air update route (go to Settings > General > Software Update on the device) as this method downloads only the deltas that are much smaller and faster to install (a 51.4 MB download for the iPhone 5 and a 32.9 MB download for the iPad mini). You can also grab the full image of iOS 6.0.2 through iTunes on your Mac (which downloads a heftier 819 MB).

All that said, some people have experienced significant battery drain after updating to iOS 6.0.2 (see “iOS 6.0.2 May Impact Battery Life,” 19 December 2012), and while toggling Wi-Fi off and back on may help, it’s worth holding off on iOS 6.0.2 unless you’re experiencing Wi-Fi problems that it might fix.

iOS 6.0.2 May Impact Battery Life

I can’t state categorically that the recently released iOS 6.0.2 for the iPhone 5 and iPad mini will hurt battery life, since evidence is still anecdotal and battery life testing requires time. And yet, while there are not so many reports to indicate that the problem is universal, or even necessarily widespread, at least three people on the TidBITS staff noticed unusual battery drains over the 24 hours after updating, and a quick sanity check on Twitter revealed a number of others who have also seen surprisingly low battery levels since updating to iOS 6.0.2.

In my case, when Michael Cohen raised the issue on our staff list at 12:30 PM, my iPhone 5 was at 73 percent. That’s a bit low, given that I’d barely used the iPhone, but I don’t know that I started the day with a full charge. However, 90 minutes later, at 2 PM, I was down to 55 percent — an 18 percent drop — without having used the iPhone at all. Another 90 minutes later, at 3:30 PM, I lost another 12 points to drop to 43 percent, and as I write this at 5:30 PM, I’m down to 28 percent, a 15-percent drop in two hours. And again, apart from the occasional push notification from Twitter turning the screen on, I haven’t used the iPhone at all during this time.

I am not seeing the problem that bit me when I first upgraded to iOS 6, when Safari bookmark syncing to iCloud was failing repeatedly (see “Solving iOS 6 Battery Drain Problems,” 28 September 2012). None of the logs in Settings > General > About > Diagnostics & Usage > Diagnostics & Usage Data show anything that looks unusual at this point.

Our speculation, based on some quick testing that Michael did, is that the problem is related to a change in Wi-Fi behavior, which maps with Apple’s sole release note for iOS 6.0.2: “Fixes a bug that could impact Wi-Fi” (see “iOS 6.0.2 Squashes Unspecified Wi-Fi Bug in iPhone 5 and iPad mini,” 18 December 2012). Michael started a car trip that takes him past numerous Wi-Fi access points in Santa Monica with the battery at 97 percent. When he arrived at LAX, his iPhone 5 was warm and had dropped to 85 percent. He then put it in Airplane Mode for the return trip, and arrived home with a cool iPhone and no change in battery percentage. Of course, Airplane Mode turns off all other

radios too, so it’s far from conclusive, but indicates that the problem may be related to wireless communication in some fashion. Subsequently, I manually toggled Wi-Fi off and back on, and that seems to have resolved the problem for my iPhone 5.

For the moment, my advice to anyone who has not noticed any Wi-Fi-related problems with iOS 6.0.1 on an iPhone 5 or iPad mini is to hold off on upgrading to 6.0.2 until more is known. If you are experiencing Wi-Fi weirdness, it may be worth the as-yet-unquantified risk to battery life to improve your wireless connectivity. And if you have already upgraded, be a little more aware of your battery life in case you need to charge more often to get through a long day.

Google Drops Google Sync for Most iOS Users

For a while now Google’s Help pages have been steering users away from using Google Sync, which uses Microsoft’s Exchange ActiveSync technology for mail, contact, and calendar syncing. Now the future picture of device syncing with Google services is clear, albeit not particularly rosy: in a page titled “Google Sync End of Life,” the company says, “Starting January 30, 2013, consumers won’t be able to set up new devices using Google Sync.” Instead, users are instructed to set up new devices using the following protocols for device syncing: IMAP for email, CardDAV

for Contacts, and CalDAV for calendars.

For those who have already set up their devices to use Google Sync, the end of the world is being postponed indefinitely: Google states in the same document that the service will continue to work for existing Google Sync devices, and that Google Sync will continue to be offered to new users of Google Apps for Business, Education, and Government. (Note that we haven’t found a good way to convert a regular Gmail account to a Google Apps account.)

Though Google Sync has never progressed beyond beta status, on iOS it has been the only syncing method for Gmail accounts that provides push email to iOS devices; the open-standard IMAP service offered by Google does not. In the early days of iOS (before it was even known as iOS), device owners who wanted push email and who had both Gmail accounts and Exchange accounts (the latter perhaps through work or school) faced a difficult choice: the operating system allowed only one Exchange ActiveSync account per device, so device owners had to choose which account to use on their devices. Recent versions of iOS have provided for multiple Exchange ActiveSync accounts on one device, so users could set up multiple Gmail and Exchange accounts on

their devices and get push email through all of them. Those were the glory days.

And those days are coming to an end. In fact, those days are already over for Google Calendar users: Google Calendar Sync was made unavailable to new (non-paying) users on 14 December 2012, although it will continue to function for those who have already set it up on their devices. New users instead will have to set up CalDAV accounts to access their Google calendars on iOS devices. They can do that, of course, through the Gmail setup assistant on iOS as described in Google’s current Calendar Help document. Similarly, those who wish to sync their Google contacts on iOS via CardDAV can also use the Gmail setup on their devices as described in

Google’s Contacts Help document, even though the Google Sync option for contacts still remains available to new users until the end of January 2013.

The fact that Google now supports open protocols for mail, contacts, and calendars is a good thing, of course, but that goodness is not unalloyed. As noted earlier, IMAP does not provide a push email capability, so iOS users will have to set up a fetch schedule for it on their devices to be alerted to new messages in a timely manner. And with CalDAV instead of Google Calendar Sync, new calendar invitations will be seen only when users open the Calendar app on their devices — CalDAV does not push them.

For those of you who have a new iOS device and want to receive push email from Gmail on it, time’s a-wastin’: you have until the end of January 2013 to set it up.

Gigabit Internet Just out of Reach in Seattle

On 13 December 2012, the City of Seattle announced a breakthrough in a previously shelved plan to bring fiber-based Internet service directly to homes and businesses. A partnership with a private firm, Gigabit Squared, and the University of Washington will make use of a fiber backbone that the city has built over many years to serve its own needs, and which it also leases for Seattle-based county, state, federal, and school uses. A previous plan had called for issuing revenue-backed bonds to fund the effort directly.

But the service won’t initially cover the entire city. Instead, the program will launch in 12 neighborhoods that comprise about 50,000 homes and businesses, and it will be connected directly to individual buildings: this is called fiber-to-the-home (FTTH) or fiber-to-the-premises. It will also use gigabit wireless (over licensed dedicated frequencies) to beam service from within the coverage area using highly directed line-of-sight transmissions to nearby multi-unit buildings, like apartments, as well as businesses. There’s also a vague description of building a high-speed wireless cloud in covered areas, but it’s unclear at the moment if that’s Wi-Fi or something else. All these

services have symmetrical throughput, offering the same bits-per-second upstream and downstream.

What’s interesting about this proposal, as far as it’s currently defined, is that it’s not a “triple-play” service that includes broadband, video, and voice. Some firms offer a “quad play” that adds a cell service, too. (The “play” is a baseball metaphor here: a company makes a triple play to “win” in the business.) Most of the city-wide fiber efforts to date, whether with private partners or run by cities or appropriate public utilities, have focused on the triple play.

But the triple-play approach requires provisioning services. Instead of having a big, dumb Internet pipe, video gets a dedicated chunk of broadband, as does voice. These provisioned services are designed to provide quality comparable to having a dedicated wire (like cable TV or a hardwired phone line). That’s no longer necessary when you have gigabit service, though, or even, say, reliable 25 to 50 Mbps service — so long as you aren’t beholden to the specific 24-hour-a-day, multi-channel video offerings of cable and satellite. Voice, too, can be easily replaced with Skype, Vonage, and other services. (For more on smart and dumb pipes, see “New App.net Social Network

Aspires Beyond Chat and Ads,” 28 August 2012.)

Seattle’s plan may also be an attempt to avoid too much “disruption” at once. If the gigabit plan doesn’t compete with cable services, Comcast still has a role to play. And, one imagines, Comcast may need to step up its game in terms of pricing and higher-tier bandwidth services, which are offered in some markets. CenturyLink, Seattle’s incumbent phone provider, has no plan for fiber to homes and businesses, and its DSL offerings are slow and erratic. It has a fiber-to-the-neighborhood (FTTN) plan that allegedly brings 12 to 24 Mbps of raw throughput, but it isn’t price-competitive with cable. Landlines are being rapidly shed by households, and DSL speeds have been unable to keep up in practice with cable modems, and can’t

hold a candle to fiber.

(For those having trouble keeping track of who is the “phone company” these days, US West was the Baby Bell that served most of Washington State as well as a bunch of the Northwest and a few other scattered states. Qwest acquired US West, and then was itself sucked into CenturyLink. CenturyLink used to be mostly a rural telephone company known as CenturyTel, but it acquired Sprint’s spun-off landline business, Embarq, and then Qwest. Verizon has been urged to sell its landlines, too. Landlines are a dying business.)

You’d think phone companies would be ideally placed to put in fiber to the home, but they all switched their focus to the high growth and profit in mobile voice and broadband. AT&T has its U-Verse FTTN, which gets decent reviews, but has only 7 million broadband subscribers (out of about 30 million locations to which it’s available) in AT&T’s vast service area, and it isn’t growing. The firm’s CEO just said that it’s more or less done building out the offering. Verizon’s FTTH service, FiOS, could carry gigabit, but doesn’t. And FiOS’s 300 Mbps down/65 Mbps up offering costs $210 per month, far higher than the gigabit services in cities that have already deployed FTTH. Verizon has also more or less said it

won’t build out more FTTH, too, with only about 3 million customers taking the service of 15 million to whom it is available.

The joy of gigabit Internet is unfettered access, of course, but it’s not necessarily about today’s Internet. As I wrote recently in the Economist, citing Cyrus Farivar’s Ars Technica coverage, most Web sites and services currently either can’t keep up with gigabit connections or simply don’t have anything to fill the pipe. If you need only a few Mbps to get the best possible HD streaming movie over the Internet, gigabit service provides you the overhead to ensure you can always get it, assuming the connection to Netflix, Amazon, or others is clear. (For

backups and other huge data transfers, gigabit already shines.)

No, gigabit Internet paves the way for the next big thing: whatever services develop for customers who always have massive bandwidth available, whether it’s super-high-quality two-way teleconferencing for remote workers and remote offices (something that can be done with modest quality today), the delivery of Blu-ray-quality video as temporary 50 GB downloads that take just a few minutes or that can be burned to Blu-ray disc for future use, or high-bandwidth gaming that provides more real-time interaction at higher rendering resolutions. In the short term, always getting the highest possible speed from any site or service probably suffices.

I’m peeved because I don’t live in any of the 12 initial neighborhoods, although I’m not far away: a stone’s throw from the University of Washington and the north end of one of the large neighborhood segments south of the university. I’ll just have to wait and sob over my “mere” 25 Mbps cable connection, itself the envy of many in Seattle served only by a second-tier cable firm or CenturyLink. Many of those areas of the city are, of course, getting fiber first, and they will soon be able to lord it over me. At least Jeff Carlson and Agen Schmitz — the other Seattle-based members of the TidBITS staff — aren’t any closer to a covered area than I am, or I’d never hear the end of it.

The Insourcing Boom and Apple’s Influence

Charles Fishman’s excellent article “The Insourcing Boom” in The Atlantic barely mentions Apple — just one instance of “iPhone-sleek” to evoke a design goal — but the company’s ethos is everywhere in the piece.

Fishman writes about how General Electric has moved manufacturing of some of its products like washing machines and refrigerators back to the United States from China. On the surface, this seems absurd, because we all know that labor costs in the United States are vastly higher than costs in China (about 30 employees in China for the price of one employee in the United States, he notes). But it turns out that labor is no longer the most important factor: oil prices have risen over the past decade, making it much more expensive to ship goods by boat; the typical five-week travel time between continents is becoming a liability as the market demands faster revisions to products.

However, what’s really crucial turns out to be design. To manufacture a water heater called the GeoSpring in their own facilities (which have remained largely empty for years), GE’s engineers realized that actually building the thing was a mess.

The GeoSpring suffered from an advanced-technology version of “IKEA Syndrome.” It was so hard to assemble that no one in the big room wanted to make it. Instead they redesigned it. The team eliminated 1 out of every 5 parts. It cut the cost of the materials by 25 percent. It eliminated the tangle of tubing that couldn’t be easily welded. By considering the workers who would have to put the water heater together — in fact, by having those workers right at the table, looking at the design as it was drawn — the team cut the work hours necessary to assemble the water heater from 10 hours in China to 2 hours in Louisville.

In the end, says Nolan, not one part was the same.

So a funny thing happened to the GeoSpring on the way from the cheap Chinese factory to the expensive Kentucky factory: The material cost went down. The labor required to make it went down. The quality went up. Even the energy efficiency went up.

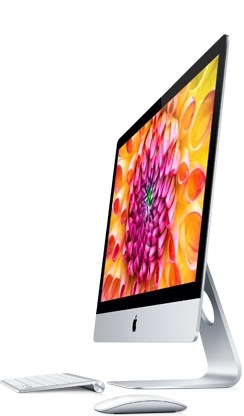

Even if you know Apple just for its products, you know that design is a huge focus at the company. Design is the company. And the way the iPhone appears or the thinness of the latest iMac is just a small part of the products’ design.

To make their products as sharp and beautiful as they are, Apple must also design the manufacturing processes to create them. The fit and finish of an iPhone 5 is unmatched because a machine with high-resolution cameras examines the partially assembled phone in front of it, snaps photos and precise measurements of it, and then chooses from 725 versions of one piece to find the one that fits best (watch the iPhone 5 video starting at 4:31).

In the documentary “Objectified,” Apple Senior Vice President of Design Jonathan Ive says that much of the work that goes into coming up with a new product design is focused on building the machines and processes that will create the product. For example, Apple designed the machines that turn single slabs of aluminum into the cohesive frames of the MacBook Air and MacBook Pro laptops; making the body a single piece increases rigidity, while using aluminum keeps the weight down.

(Apple is a great source of behind-the-scenes machine assembly pr0n, which also shows that it knows this manufacturing is a significant competitive advantage. After you’ve held an iPhone 5, just about any other phone on the market feels like cheap plastic.)

So Apple has been aware for years of the advantages of designing systems and manufacturing processes catered specifically to their products. And yet, nearly all of its production happens in China.

Fishman talks also about the disconnect between a product’s designers and engineers in the United States and the people doing the manufacturing in China. It’s not just an issue of speaking different languages.

It happens slowly. When you first send the toaster or the water heater to an overseas factory, you know how it’s made. You were just making it — yesterday, last month, last quarter. But as products change, as technologies evolve, as years pass, as you change factories to chase lower labor costs, the gap between the people imagining the products and the people making them becomes as wide as the Pacific.

Apple benefits from several advantages in this respect, made possible largely because Apple has so much money to address the issues. Apple employees spend time in the factories, and have built up perhaps the world’s most impressive supply chain. Back when Apple CEO Tim Cook was vice-president of operations, an important manufacturing problem came up. According to an article by Adam Lashinsky at CNN:

“This is really bad,” Cook told the group. “Someone should be in China driving this.” Thirty minutes into that meeting Cook looked at Sabih Khan, a key operations executive, and abruptly asked, without a trace of emotion, “Why are you still here?”

Khan, who remains one of Cook’s top lieutenants to this day, immediately stood up, drove to San Francisco International Airport, and, without a change of clothes, booked a flight to China with no return date, according to people familiar with the episode.

Apple also circumvents the time-to-market issue by flying new products from the factories directly; when you place an order for a new model of iPad, for example, you can track its progress from the factory to the United States via FedEx or UPS tracking number. Loading many — hundreds? — of 747 cargo planes full of devices so they arrive in people’s hands the first day of availability is massively expensive. But Apple has the money to do it, the margins to afford it, and millions of customers willing to pay for it. (Here’s another area where design is crucial: it’s no coincidence that Apple’s product packaging has shrunk over the years. Smaller boxes mean you can fit many more onto a pallet, which translates to hundreds more

devices that can be carried on a single plane, reducing the cost of fuel per device.)

Tim Cook is an operations genius, and is no doubt aware of the points raised in Fishman’s insourcing article. Which is why it’s not a surprise that Cook told Brian Williams of NBC that Apple plans to begin producing one of its existing Macs in the United States in 2013. Given the company’s extensive experience designing manufacturing in the past, I have no doubt it’s taking the same skills and figuring out how to make it work in the US.

Fishman’s article is a great look at an exciting new chapter in U.S. manufacturing. Although it was published just a couple of weeks before Cook made his announcement, the article has Apple written all over it.

Examining Apple’s Security Efforts in 2012

Apple’s security is, across the board, stronger now than at any time in the nearly eight years I’ve been researching and writing about the company’s products and services. Which is important, since Apple also faces more security challenges than at any time in its past.

When I first began writing about Apple security, the situation was bleak yet meaningless. Bleak thanks to a company that didn’t prioritize security and not only responded poorly to issues, but also left the platform wildly exposed to potential attacks. Meaningless, since said attacks never actually happened in the real world. As much as I may have fretted over the lack of security features or what the future might hold, my worries were trifles considering the absence of actual problems for users.

Outside of Mac OS X users, vanishingly few people used .Mac, the iPhone was brand new and locked down, iOS hadn’t yet been named, there was no iPad, iPods were still music players, and Apple products were almost universally banned from enterprises.

Today Apple is the second most popular brand in the world, trailing only Coca-Cola. It is also one of the most profitable companies in the world, with massive sales in smartphones, laptops, and tablets — a category Apple essentially defined — and a reported 85 million users of the iCloud online service. Never before have so many users relied so much on the security efforts of the company from Cupertino.

This popularity hasn’t been ignored by the media, security researchers, or criminals. The slightest Apple security or privacy glitch creates an instant media frenzy, the online equivalent of the local news telling parents that drinking water will poison their children. 2012 also saw the first widespread, albeit non-damaging, Mac malware. “BYOD” (bring your own device) is the biggest hot-button issue in enterprise security, and is predominantly driven by user demands that their organizations support iPhones, iPads, and Macs. I can no longer walk into a meeting with enterprise IT without at least some Macs or iPads in the room, officially supported or not.

This is a nearly complete reversal from just five years ago. And while Apple seems up to the task, it’s clear that the intensely private company is struggling to find the balance between its close-mouthed corporate culture and its new responsibilities as a global technology leader in the post-PC era. Let’s look at what Apple has done with OS X, iOS, and its cloud services.

OS X — It’s trite to say OS X 10.8 Mountain Lion is the most secure version of OS X yet, since it’s also the latest version. But Mountain Lion did introduce one significant new security feature with the potential to reduce the risk of widespread malware on Macs even as the platform increases in popularity.

Gatekeeper (which I described extensively in “Gatekeeper Slams the Door on Mac Malware Epidemics,” 16 February 2012) is a new feature in OS X designed to alter the economics of mass malware. In its default setting, Gatekeeper allows the user to run only those downloaded applications that come from the Mac App Store, or that are digitally signed by the developer using a key issued by Apple. Since most widespread malware today relies on tricking the user into installing and running unapproved applications, this presents a serious roadblock to attackers.

Applications in the Mac App Store are now required to implement sandboxing and undergo review by Apple. This reduces both the chance of a malicious app making it into the Mac App Store, and the potential harm of either a malicious app or one compromised by an attacker. Sandboxing on other platforms (like iOS) has been shown to be an effective technique of increasing the cost of attacks, even if the sandbox is broken. Both Mac App Store applications and those independently distributed and signed with an Apple-issued Developer ID are digitally signed, which helps the operating system detect if the application was tampered with; again, adding yet another roadblock attackers need to circumvent.

Mandatory sandboxing hasn’t been popular among developers, but as I discussed in “Answering Questions about Sandboxing, Gatekeeper, and the Mac App Store” (25 June 2012), it is an incredibly important security tool for protecting users, even if we lose some functionality. Unfortunately, since sandboxing is mandatory in the Mac App Store, that means it has also been caught up with otherwise-unrelated issues in distributing applications through Apple that complicate the lives of developers.

While Gatekeeper certainly won’t prevent all infections, and I’m sure there is still a contingent of Mac users who will be tricked into installing malware, it disrupts the economics of fooling users into installing malicious software. Today’s Internet criminals are in it for the money; tools like Gatekeeper dramatically increase the cost of running a malware campaign, reduce their profits, and make the Mac a less appealing target.

Gatekeeper is only one of a number of security controls built into OS X. FileVault 2, introduced in 10.7 Lion, transparently encrypts hard drives to protect data in the event of physical loss. It’s a massive improvement over the original FileVault, so much so that Apple probably should have used another name due to all the negative connotations associated with the previous version. Mountain Lion also extended FileVault 2 to cover external drives, including Time Machine backups (with a little extra work). FileVault can even be combined with Find My Mac to wipe your hard drive remotely in case of loss, although this can be dangerous if anyone accesses your iCloud account and you lack current backups (see “Watch TidBITS Presents “Protecting Your Digital Life”,” 22 August 2012).

In terms of the core operating system, Mountain Lion extends ASLR (Address Space Layout Randomization), a powerful tool to limit the ability of attackers to exploit vulnerabilities, to the kernel itself. Mountain Lion also added some additional memory exploitation protection techniques for those on current processors, like the Core i5 and i7, included in new Macs. These processors include extra hooks that operating system vendors like Apple can leverage to further complicate an attacker’s efforts.

In 2012 Apple also showed a clear ability to make difficult decisions in favor of protecting users from the most common forms of attack. In response to the Flashback malware infection earlier in the year (see “How to Detect and Protect Against Updated Flashback Malware,” 5 April 2012), Apple began tightening the screws on the two most common sources of Web browser based malware infections: Java and Adobe Flash.

Java is an extremely common source of infections across Macs, Windows PCs, and any other computing device it runs on. Java applets are easy to embed in Web pages and tend to run, by default, in the Web browser. Java is also very difficult to sandbox off from the rest of the operating system. Thus a good Java exploit dropped on a Web page may easily infect most visitors (though generally on a platform-specific basis). This was especially pernicious on Macs since Apple did a poor job of maintaining its own version of Java, often letting it go unpatched for weeks or months after the official version was fixed and thus giving potential attackers a roadmap to success.

When Java attacks like Flashback started to increase, Apple performed three key actions via a series of updates. First, Apple disabled Java from running not only in Safari, but in any major Web browser on your Mac unless you explicitly turned it on. Even then, OS X would disable Java again in 90 days if you didn’t use any Java applets. Second, Apple also stopped installing Java on Macs by default at all (before Flashback), although it’s fairly common for users to add it back in. Third, Apple handed the responsibility for updating Java on the Mac back to Oracle, so now Mac users receive patches at the same time as all other platforms. Java is now uninstalled by default, blocked in your browser unless you explicitly enable and use it,

and patched on time.

Apple then extended similar protections to Adobe Flash, another common source of browser-based vulnerabilities. Although Flash hasn’t been installed by default for years, it was nearly universally installed by users, and rarely updated. Apple and Adobe worked together (sort of) to address this situation. Recent versions of Flash include a self updater to ensure users are using the latest, patched versions (see “Flash Player 10.3.181.26,” 23 June 2011). Since many Mac users weren’t using the self-updating versions, an Apple security update disabled any version of Flash that lacked the self-updating function, essentially forcing users to update.

It’s hard to overstate the effectiveness of these combined improvements. Our Macs are well-protected against physical loss thanks to FileVault. The combination of Gatekeeper, the Mac App Store, code signing with Developer IDs, and sandboxing dramatically raise the cost to attack Macs by tricking users into installing malware. The constant improvements in inherent operating system security continue to reduce the chances of attackers exploiting vulnerabilities. And by reducing the exposure to Java and Flash in the Web browser, the cost to attack Mac users through Web vulnerabilities is materially higher.

Apple showed its hand with Mountain Lion and ongoing security updates — the company is focused not only on hardening the operating system, but addressing common user behaviors that enable attackers. This combination won’t stop every attack, nor even every widespread attack, but it is hard to imagine Macs ever suffering an ongoing malware epidemic even as they increase market share. The key takeaway is that all these technologies are aimed at attacking the economics of malware.

iOS — There’s a short version and a long version of the iOS security narrative. The short version? iPads and iPhones are the most secure consumer computing devices available. They have never suffered any widespread malware, exploits, or successful attacks in their entire history. None. Zero. Zip.

The long version? iOS is hardly immune from security issues. There is no perfect security, and iOS suffers vulnerabilities just like every other platform. iOS 6 itself contained well over 100 fixes for various security flaws. But iOS 5 was difficult for attackers to exploit, and iOS and Apple’s latest processors (the A6 and A6X chips) continue to add ever more security hardening. The best indicator of iOS security is the availability of jailbreaks, since every jailbreak is technically a security exploit. As of this writing, there are no jailbreaks available for iOS 6 on the iPhone 5 or fourth-generation iPad (using the A6 and A6X processors), and only limited (tethered) jailbreaks for the iPhone 4S, the iPad 2, and the

third-generation iPad (which use the A5 processor).

Another strong indicator of iOS security is that digital forensics firms, those who produce the software used by law enforcement to recover data from mobile phones and computers, are as yet unable to crack data protected by the highest level of iOS encryption enabled by default (for email and participating apps) when you set a good passcode.

iOS is highly restrictive, allowing only apps from the App Store, extensively sandboxing applications from each other, nearly eliminating shared storage, code-signing all apps to limit tampering, and disallowing background applications. All this is on top of a hardened platform that makes wide use of security features built into the underlying hardware.

The main security enhancements in iOS 6 were the addition of kernel ASLR and other memory protections similar to those in OS X, which isn’t surprising since the two operating systems still share much of their code base. iOS 6 also added a series of enhanced privacy protections. Apple stopped allowing the unique device identification (UDID) to be available to apps in order to limit user tracking by independent developers. Also, users must now explicitly approve access to locations, contacts, calendar entries, and photos on a per-app basis, and can revoke those rights at any time through the Settings app. This move came in direct response to widespread reports of abuse by some application developers accessing private data that their

applications didn’t technically need.

Apple also added some additional features to support enterprise deployments of iOS, such as a global proxy setting to manage Internet connections, blocking of iMessage, Passbook, Game Center, Photo Stream sharing, and the iBookstore (in addition to existing application and feature limits), time-limited configuration profiles, and improved certificate and profile management. I spend a lot of time talking with enterprises about iOS security, and their main concerns are supporting employee personal devices while still protecting enterprise data, not malware or other external attacks.

As strong as iOS security is, we know it isn’t perfect. Vulnerabilities are discovered, new jailbreaks are created, and rumors in the security world are that some governments have paid hundreds of thousands of dollars for single exploits to enable them to hack iPhones and iPads remotely. Strong encryption (called Data Protection) covers only email messages and attachments by default, and other apps that enable the API, potentially leaving large amounts of data recoverable if you lose the device. Also, shorter passcodes like the default four digits can still be broken via brute force attacks.

None of these should be concerning to the average user not facing a hostile government (which, we admit, does happen in parts of the world). Government-level exploits are rare, expensive, and not wasted on the average user. If you lose an iOS device, the odds are against the person finding it trying to steal your data — he or she is far more interested in selling the device. If you are concerned with law enforcement or a government peeking at your information, using a longer passcode and Data Protection-enabled apps will probably thwart their efforts.

As for the “Great Mobile Malware Epidemic” constantly predicted every year by various publications and security companies? It doesn’t seem to be an issue for iOS.

iCloud and the iTunes Store — Discussing Apple’s online services — iCloud and the iTunes Store — is far more difficult, thanks to a complete lack of transparency from Cupertino. Unlike OS X and iOS, security updates are handled on Apple’s servers with no public notification. Apple makes no public statements regarding the security particulars of either platform, and what little information is publicly available is little more than marketing statements. Within those limitations, here is what we can infer.

Apple states that all iCloud communications are encrypted, and all data is encrypted when stored on its servers, with the exception of Mail and Notes, which are encrypted only over the network (stored data encryption is rare for online mail services). This data is protected using keys Apple manages, and thus Apple employees can technically see your content. The easiest way to determine if any online service can access your data is to see if you can access the content through a Web browser. Unless the company writes complex code to encrypt and decrypt within your browser (which is extremely rare outside password-related services like LastPass), that means its Web server, and thus

its employees, can access the data.

An important aspect to iCloud security is that your iOS device backups in the cloud are potentially accessible to Apple, or to anyone with a warrant or subpoena. If you’ve ever restored from iCloud, you probably noticed that you have to re-enter most of your usernames and passwords, which you don’t need to do if you restore from a local and encrypted backup. That’s because Apple scrubs the keychain for unencrypted backups, either local or iCloud.

iCloud data is not stored encrypted on your Macs or iOS devices, unless you turn on some other additional encryption. The network connections to Apple are encrypted, and the data encrypted on Apple’s servers, but it is accessible by Apple.

Apple’s security guide for iOS states that both iMessage and FaceTime support “client-to-client” encryption. The most common interpretation of this means your messages are encrypted even from Apple. But since Apple manages the encryption certificates and keys, there’s always the chance that an Apple employee could perform a “Man in the Middle” attack to sniff your data. My belief is that, although Apple has this capability, at worst it is something only accessible to and used by law enforcement, like any other wire tap, and we have no idea if that has ever occurred.

There isn’t much more to say about iCloud. Apple doesn’t talk about security incidents, but I’m unaware of any that have been reported publicly. Apple also doesn’t discuss iCloud security controls, such as how the company restricts access by employees to your data, so we have no idea how good or bad those practices are. On the upside, although Apple’s privacy policies technically allow the company to look at or share your private data, we are unaware of Apple mining your data for other purposes, as do Google, Facebook, and other advertising-supported services.

The iTunes Store and iTunes in the Cloud also use encrypted communications, but obviously handle less-sensitive information. The main security concern with them is credit card data, and there have been reports of illegal purchases, phishing attacks, and other financial crimes associated with iTunes Store (including the App Store and Mac App Store) accounts. Earlier this year, Apple implemented enhanced security, including sending you email when new devices make purchases, notifying you via email of account changes, and requesting account verifications at least once a year. Also, Apple does mine your iTunes usage for Genius and ratings, but, again, we do not believe any user-specific data is ever shared or used for

advertising.

It’s hard to know what’s really going on since Apple doesn’t make public statements about the reports of iTunes Store attacks, and there is often a distinct lack of consistency that might support getting at the root of the problem. If there even is a problem or flaw, we honestly don’t know.

Unfortunately, silence fosters fear when it comes to active security incidents. Once incidents become public enough, users rightfully worry and look to Apple for answers. But this is a lesson Apple will learn for itself, and adapt to in its own way. While I don’t ever expect to see Apple respond as quickly and publicly as a company like Microsoft, I do see early signs that Apple is taking security communications more seriously.

Four events from the last two years show this gradual change. During the Lion development process Apple invited select security researchers to participate in the beta testing for free, instead of hoping they might join Apple’s official developer program. Before the release of Mountain Lion, Apple pre-briefed a security researcher (yes, me) under NDA so the rest of the press would have a security expert to discuss Gatekeeper with. Apple also, for the first time, released a detailed iOS security guide discussing the operating system internals. Finally, at this year’s Black Hat security conference Apple delivered a presentation for the very first time,

talking about iOS security but refusing to take questions.

Culture is difficult to evaluate. It lacks the objective indicators of operating system or hardware updates, especially when much of the discussion takes place in private or under NDA. On the objective side, I see Apple adding more security features, giving them a more prominent role in the operating systems, and responding more quickly and directly to security issues. Subjectively, the company is still secretive, but far more responsive and communicative than in the past.

It’s clear Apple recognizes that security plays an essential role in maintaining the growth of the company. To that end, the company has not only been more responsive, albeit in its own way, but has made important long-term investments in the security of the Apple ecosystem. These efforts paid off in 2012, and we are likely to see them continue to pay off for years to come.

TidBITS Watchlist: Notable Software Updates for 7 January 2013

Carbon Copy Cloner 3.5.2 — Bombich Software has released Carbon Copy Cloner 3.5.2 with a change in notification support for OS X 10.8 Mountain Lion users, shifting from Growl to Notification Center. (Mike Bombich details the reasons for the switch and offers a workaround to generate Growl notifications before or after scheduled backups.) The update improves handling MacFUSE filesystems, displays a “bread crumb”-style indicator of the path to the folder selected as a source or destination, improves how Carbon

Copy Cloner prevents a system from going to sleep during a backup, and fixes an issue with the OS X 10.8.2 Supplemental Update that prevented a backup from taking place. Additionally, the system requirements for a remote Mac are now the same as those for your Mac running Carbon Copy Cloner — notably, backing up to a PowerPC-based Mac won’t work anymore. ($39.95 new, free update, 10.7 MB, release notes)

Read/post comments about Carbon Copy Cloner 3.5.2.

Airfoil 4.7.5 — Rogue Amoeba has released Airfoil 4.7.5, which restricts searches to your local network to prevent possible issues with Back to My Mac and iCloud. The update also fixes an issue with failing to open a DVD in Airfoil Video Player, prevents a crash if the Transmit button gets pressed exactly as an output disappears, and provides some small improvements for Retina displays (a full Retina display update is yet to come). ($25 new with a 20-percent discount for TidBITS members, free update, 10.6 MB, release notes)

Read/post comments about Airfoil 4.7.5.

SpamSieve 2.9.6 — C-Command Software has released SpamSieve 2.9.6 with a fix for a bug that slowed down spam-filtering operations in Postbox when running OS X 10.8.2 Mountain Lion. The update now understands that @icloud.com, @me.com, and @mac.com addresses are equivalent for training purposes in Apple Mail, and SpamSieve also offers to load addresses from Microsoft Outlook directly rather than use the less-than-reliable Sync Services to perform that task. The release also removes flags from a message trained as good in Apple Mail, improves handling of invalid data received from a mail program, and improves interaction

between SpamSieve and server-based spam mailboxes to prevent a trained spam message from ending up in the local spam mailbox. ($30 new with a 20-percent discount for TidBITS members, free update, 10.4 MB, release notes)

Read/post comments about SpamSieve 2.9.6.

BusyCal 2.0.2 — BusyMac has released BusyCal 2.0.2, a minor update that puts paid to several bugs. The update fixes some unspecified Google Calendar syncing bugs, a bug that prevented past due to-do items from showing in the To Do List, bootstrapping bugs with Daylite and Zimbra CalDAV Servers, and a bug that occurred when entering start times between 0001-0059 in 24-hour time. It also adds an option to print multiple months/weeks when viewing a custom number of weeks/days. ($49.99 new, but currently selling for $29.99 solely via the Mac App Store, free

update, 8.3 MB, release notes)

Read/post comments about BusyCal 2.0.2.

Typinator 5.4 — With the release of Typinator 5.4, Ergonis’s typing expansion utility now enables you to export abbreviation sets using either tab-delimited text format or comma-separated value (CSV) format. The update also improves imports from TextExpander with conversion of date/time calculations, special keys, and input fields. The release also avoids a delay after opening the Typinator window for the first time, fixes an issue with Default Folder X, and provides improved compatibility with Photoshop CS6 droplets. (€24.99 new with a 25-percent discount for TidBITS members, free update, 5.0 MB, release notes)

Read/post comments about Typinator 5.4.

BBEdit 10.5.1 — Bare Bones Software has released BBEdit 10.5.1, a maintenance release devoted exclusively to fixes after the recent release of 10.5 (see “BBEdit 10.5 Adds Versions and Brings Web Sites into Projects,” 4 December 2012). Amongst the voluminous bug squashes listed in the often humorous release notes, the update ensures the Markup menu’s H1 through H6 commands render the correct heading level, fixes a bug that would reinstall command line tools if they were already present and

up to date, adjusts behavior for the clippings system to avoid a crash at startup, corrects line spacing for printed documents, and fixes a bug in which attributes couldn’t be removed from existing markup by using the Markup Builder panel. ($49.99 new from Bare Bones or the Mac App Store, free update, $39.99 upgrade from pre-10 versions, 12.6 MB)

Read/post comments about BBEdit 10.5.1.