TidBITS#1309/22-Feb-2016

The big news this week is how Apple and the FBI are locked in an important battle over civil liberties; Adam Engst has two articles in this issue that attempt to explain the dustup over the FBI asking Apple to help unlock a terrorist’s iPhone. More prosaically, Apple has issued an update to resolve Error 53, which was disabling iPhones that had been repaired by outside parties. Apple Pay is now available in China, where it’s proving popular, and it may soon be usable at ATMs in the United States. Finally, we’re soliciting your suggestions for the best personal finance apps for the Mac — we’ll publish the results in next week’s issue! Notable software releases this week include Mailplane 3.6.2, Microsoft Office 2016 15.19.1, Evernote 6.5, and Airfoil 5.0.

Apple Issues New iOS 9.2.1 to Fix Error 53

We’ve been following the saga of Error 53, the mysterious error message that’s been rendering iOS devices unusable. Last week, Error 53 was traced to mismatches between the Touch ID sensor and the Secure Enclave coprocessor, caused by repairs performed by technicians not authorized by Apple (see “What “Error 53” Means for the Future of Apple Repairs,” 15 February 2016). Thankfully, Apple has now issued a fix for affected users.

In a statement to TechCrunch, Apple explained itself:

We apologize for any inconvenience, this was designed to be a factory test and was not intended to affect customers. Customers who paid for an out-of-warranty replacement of their device based on this issue should contact AppleCare about a reimbursement.

To address the problem, Apple has issued a new version of iOS 9.2.1 specifically for those with this issue. Unless you force a restore in iOS, you will not receive this update, nor do you need it.

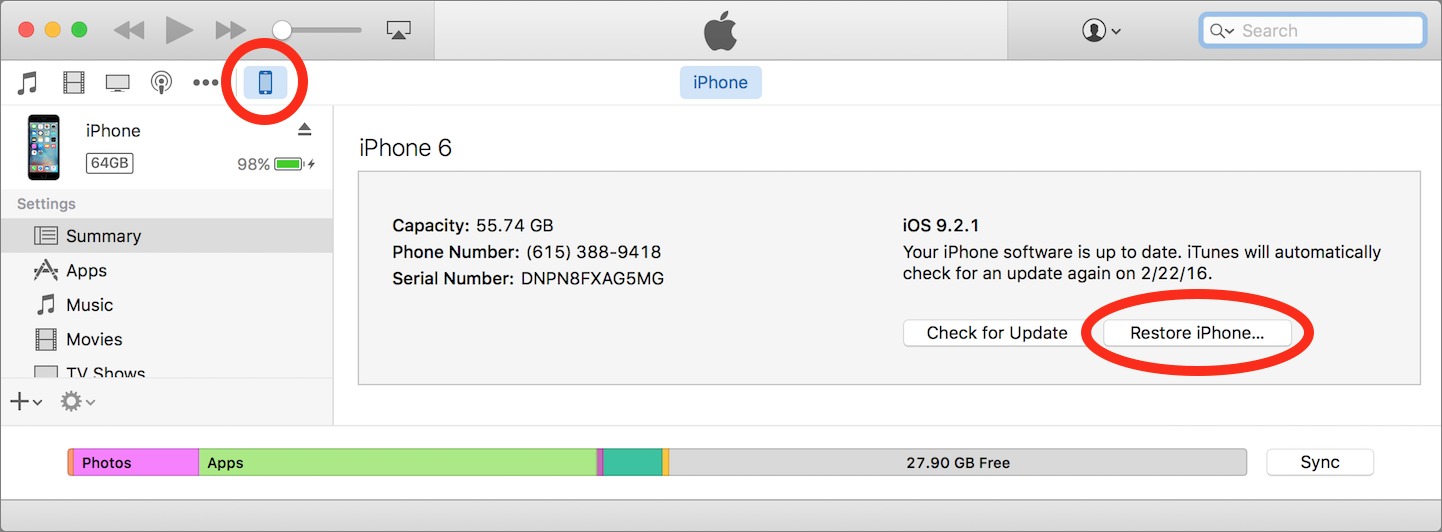

If you’re seeing Error 53, try restoring your device via iTunes by connecting it to your computer with a USB-to-Lightning cable, opening iTunes, clicking the iPhone (or iPad) button, and then clicking Restore iPhone (or iPad). Check Software Update to be sure you have the latest version of iTunes before restoring.

If you see an error message when you try to restore your device, a new Apple support article recommends performing a force restart on the iOS device, by pressing and holding the Sleep/Wake and Home buttons until you see the Apple logo. After that, try restoring with iTunes again.

While this fix will make an Error 53-afflicted device operable again, Touch ID will not function, as it shouldn’t, given that its pairing with the Secure Enclave has been compromised. If you saw Error 53 after Apple or an Apple Authorized Service Provider repaired your device, contact Apple Support for a free repair or replacement. However, if your device was repaired outside of official Apple channels, you’ll have to pay Apple the out-of-warranty repair price to restore Touch ID, which should run between $109 and $149.

We hope this fix makes its way into the upcoming iOS 9.3 as well, so users who have had their screens or home buttons repaired by independent technicians will be able to update in the future without worrying about Error 53.

Apple Pay Expands to China, Coming to ATMs

Apple Pay has arrived in China, and the demand so far has been incredible. Mashable reported that within 1 hour, 10 million people had linked their bank accounts to Apple Pay, with a total of 38 million new users by the end of the business day.

However, the rollout wasn’t without its hiccups, as many Chinese customers were unable to complete the Apple Pay registration. The problem was originally reported to be caused by high demand, but Apple later explained that the service is being rolled out in waves, so it wasn’t available to the entire country at once.

Back here in the United States, Apple Pay may be coming soon to an ATM near you. TechCrunch reported last month that Bank of America and Wells Fargo are working on integrating Apple Pay in their ATMs, and TidBITS reader Alan Forkosh has spotted a Bank of America ATM equipped with an NFC reader, which would be required for Apple Pay. However, Forkosh wasn’t able to get the ATM to recognize his Apple Watch, so presumably the NFC reader in that ATM hadn’t been activated yet.

Meanwhile, Apple Pay has enrolled another 45 financial institutions, bringing the total in the United States to 1,045. On the retail end, chains like Au Bon Pain, Chick-fil-A, and Crate & Barrel are rolling out the service, and Apple Pay is set to arrive at Cinnabon, Chili’s, Domino’s, KFC, and Starbucks later this year.

Vote for Your Favorite Mac Personal Finance App

Over the years, no company has toyed with the loyalties of Mac users more than Intuit. The company has published the Quicken personal finance app since the early days of the Mac, and it has received preferred treatment from Apple on a number of occasions, aiding its success. (Apple subsidiary Claris bundled Quicken with ClarisWorks in 1992 and Apple itself bundled Quicken with Performa models in the mid-1990s.)

And yet, Intuit has jerked Mac users around repeatedly. Back in 1998, the company announced it was dropping Quicken entirely (“Intuit Drops Quicken for Macintosh,” 20 April 1998), before reversing the decision just weeks later after pressure from Apple (“Quicken Speeds Back to Mac,” 11 May 1998). Quicken 2002 Deluxe made the transition to Mac OS X successfully, although subsequent versions required the Rosetta emulator to run on Intel-based Macs. That was fine for Quicken 2005, 2006, and 2007, but then development paused, with Intuit announcing that the planned Quicken Financial Life would be delayed from 2008 to 2010 (“Quicken For Mac Delayed Until 2010,” 10 July 2009). It never shipped, and in 2011, Quicken 2007 was eventually replaced by the weaker Quicken Essentials. Quicken 2007’s reliance on Rosetta meant that it wasn’t compatible with Mac OS X 10.7 Lion, forcing many users to put off that upgrade (“Intuit Reminds Quicken Users of Lion Danger,” 6 July 2011). But in 2012, Inuit released a version of Quicken 2007 that could run in Lion and later versions of OS X (“Intuit Releases Quicken Mac 2007 OS X Lion Compatible,” 8 March 2012). Eventually, Intuit moved beyond Quicken Essentials to release Quicken

2015, though it too didn’t match up to Quicken 2007 (“Quicken 2015: Close, But Not Yet Acceptable,” 2 October 2014). And finally, Intuit said last year that it was looking for a company to acquire Quicken, a process that’s still underway (“Intuit to Sell off Quicken,” 24 August 2015). Phew!

Back in 2011, when Quicken Essentials was doing a poor job of replacing Quicken 2007, Michael Cohen wrote “Finding a Replacement for Quicken” (5 August 2011) and “Follow-up to Finding a Replacement for Quicken” (20 September 2011), which did a fabulous job of helping readers understand their needs and choose from the available alternatives to Quicken. If you’re considering switching to another personal finance app, be sure to read those articles.

But it’s time to do something different, which is to provide a forum for TidBITS readers to share their opinions of the state of personal finance software for the Mac. As we did with personal information managers (“Vote for Your Favorite Mac Personal Information Manager,” 11 January 2016), we’re asking you to evaluate the personal finance apps you’ve used. The survey is embedded at the bottom of this article on our Web site or you can navigate to it directly.

A few important notes before you start clicking your answers:

- Please rate only those apps with which you have significant personal experience. That means weeks or months of use, not something that you launched once before discovering that it lacked a feature you need. Don’t enter ratings for apps you haven’t used.

- We’ve listed a lot of apps in the poll, but if we missed the one you use, let us know so we can add it. To keep this manageable, we’re focusing on Mac apps that could conceivably replace Quicken — full-featured personal finance apps. Please don’t suggest simple budgeting apps, iOS-only apps, Web apps, or anything that’s not in active development. There’s nothing wrong with using these tools, but we have to draw a line in the sand somewhere.

- Some apps will get more votes than others, so when looking at the results (click Show Previous Responses after you vote), take that into account. A lot of votes may indicate popularity (or a successful attempt to game the system), but an app with just a few highly positive votes is still worth a look.

- Ratings don’t give a complete picture, so feel free to say what you like or don’t like about apps you use in the comments for this article; we’ve seeded the top-level comment for each app, and please keep your thoughts within the appropriate top-level comment. Searching for the app name will be the fastest way to find the appropriate comment thread.

We’ll report on the results next week, calling out those apps that garner the most votes and have the highest ratings. Thanks for the help!

Thoughts on Tim Cook’s Open Letter Criticizing Backdoors

Over the past few years, Apple CEO Tim Cook hasn’t been shy about speaking out against government requests for Apple and other technology companies to introduce backdoors into their products (see “Apple and Google Spark Civil Rights Debate,” 10 October 2014). His campaign seems prescient, given that the FBI has now asked Apple to create a new version of iOS that would enable the agency to hack the passcode by brute force, and install it on an iPhone recovered during the investigation of the San Bernardino terrorist attack. Claiming that this is equivalent to the creation of a backdoor in the iPhone, Apple is

fighting the FBI’s request. Apple has published Cook’s “A Message to Our Customers” to share the company’s position.

I encourage everyone to read Tim Cook’s piece; it’s clear and convincing, and it lays out the tensions well. Apple has cooperated with the FBI up to this point in response to legal subpoenas and warrants, and Cook is careful to state both Apple’s respect for the FBI and belief that the FBI’s intentions are good. But he comes out strongly against the FBI’s desire to use the All Writs Act of 1789 to justify an expansion of its authority in a way that would enable it to compel Apple to create the necessary cracking tool (more on that in a bit).

This is completely in line with Apple’s stance on backdoors thus far, as Cook’s introduction to Apple’s privacy policy makes clear:

Finally, I want to be absolutely clear that we have never worked with any government agency from any country to create a backdoor in any of our products or services. We have also never allowed access to our servers. And we never will.

Backdoors Want to Be Free — Tim Cook’s argument in his open letter, which is supported by both security experts and many members of the intelligence community, is simple. To paraphrase:

Any tool or backdoor that enables a government or law enforcement agency to bypass a product’s inherent security features legally can also be subverted by cybercriminals and hostile governments.

Since we’re talking about the digital world here, any such “master key” would itself be digital data, and would be only as secure as the other protections afforded it. Unlike physical objects, information can’t be restricted to a single location and barricaded inside vaults protected by armed guards.

The information that comprises such a master key would inhabit an uncomfortable space. On the one hand, information wants to be free, and on the other, such information would be of incalculable value.

Let’s unpack that sentence. “Information wants to be free” was initially coined by Whole Earth Catalog founder Stewart Brand in 1984 with regard to the rapidly falling cost of publishing. In 1990, software freedom activist Richard Stallman restated the concept to incorporate a political stance, introducing the concept that what information “wants” is freedom, in the sense that wide distribution of generally useful information makes humanity wealthier. A digital master key would certainly be generally useful, if not necessarily for positive purposes, so Stallman’s point implies that it would be extremely difficult or even impossible to prevent such

information from escaping into the wild.

Preventing such an escape would be made all the harder by the fact that foreign intelligence agencies and criminal organizations alike would undoubtedly pay immense sums of money for access to such a master key. A security exploit broker called Zerodium already paid $1,000,000 for a browser-based security exploit in iOS 9 that it planned to resell to government and defense customers (see “The Million Dollar iOS Hack (Isn’t),” 3 November 2015). And that’s for something that Apple probably found and blocked in one of the updates to iOS 9. Can you imagine how much an iOS master key would sell for? And how that kind of money could corrupt people within the chain of trust for such a key?

Like Tolkien’s One Ring, the power of a master key for millions of phones would be nigh-impossible to resist (unfortunately, Apple’s latest diversity report didn’t break out the number of courageous hobbits working at the company).

Tim Cook is right: any sort of backdoor is a terrible idea that could result in immeasurable harm to the hundreds of millions of people who use Apple products, the overwhelming majority of whom have an entirely legitimate expectation that their private information will be protected from disclosure, regardless of who wants that data.

Worse, because information wants to be free, it’s now well within the capabilities of criminal and terrorist organizations to create and use their own unbreakable encryption software. Even if backdoors were required, the window in which they would be useful would likely be short, as everyone with something to hide switched to something that was guaranteed to be secure.

Why the All Writs Act of 1789 and Why Now? — The one place where Tim Cook’s open letter stumbles slightly is in its description of the FBI’s use of the All Writs Act of 1789 as “unprecedented.”

Rather than asking for legislative action through Congress, the FBI is proposing an unprecedented use of the All Writs Act of 1789 to justify an expansion of its authority.

Although the All Writs Act does indeed date to 1789, and is intentionally vague (it enables U.S. federal courts to “issue all writs necessary or appropriate in aid of their respective jurisdictions and agreeable to the usages and principles of law”), it has been used regularly in modern surveillance-related cases, some involving Apple. According to Stanford professor Jonathan Mayer in a lecture linked to by Wikipedia, the All Writs Act is used as a catch-all authority for the courts to supplement warrants, but only when:

- There is no other statute or rule that applies.

- It applies to a third party with some connection to the case.

- It is justified by extraordinary circumstances.

- Compliance isn’t an “unreasonable burden.”

It seems relatively uncontroversial that the first three requirements apply to this case. If other, more specific, statutes or rules applied, the FBI would be using them. Apple is a third party with a connection to the case through the terrorists’ use of an iPhone. And a case involving domestic terrorism certainly qualifies as an extraordinary circumstance. Less clear is what involves an “unreasonable burden.”

Before iOS 8, extracting the contents of an iPhone without unlocking it was possible for Apple, and when the company was asked to do so by courts invoking the All Writs Act, it complied. However, in a New York case that’s still pending, the judge suggested that the All Writs Act may be imposing an unreasonable burden, and it’s our understanding that Apple is using that as an opportunity to resist the government order. (For more background, read the EFF’s coverage of the situation.)

To you and me, the FBI forcing Apple to create a dumbed-down version of iOS and install it on an iPhone recovered in the San Bernardino case might seem like an unreasonable burden, if only in terms of the effort involved. But given Apple’s resources, the FBI could argue that what would be unreasonable for most companies would be well within the scope of Apple’s capabilities.

A better argument for Apple would be that the FBI is asking it to develop an actual attack against its own security software, rather than use existing capabilities, as the company had done prior to iOS 8. The “unreasonable burden” test would seem significantly harder to pass if Apple is being asked to do something that’s so far outside its corporate mandate and in direct violation of the company’s own privacy policy. While creating a tool to brute force a passcode wouldn’t technically be a backdoor (not being installed on the device itself), its capability to compromise the security of any iOS device with a Secure Enclave coprocessor would have exactly the same effect, and would be subject to the same desires from bad actors.

Regardless of how terrorists or organized crime might lust after such a tool, with it available, what would prevent law enforcement agencies from asking for it to be employed regularly?

To my mind, then, that explains why Tim Cook chose this moment to write the open letter. Apple has never before been pressured by law enforcement in such a high-profile case, and it’s conceivable that a judge who was ignorant of the technical aspects of digital security could view the circumstances as sufficiently extraordinary and the burden as insufficiently unreasonable to compel Apple to comply. More so than at any time in the past, Cook and Apple need to make clear to everyone the danger of government intervention into legitimate encryption technologies. This case, or one like it, very well may end up in the U.S. Supreme Court, and the more precedent there is of judges being dubious of law enforcement requests, the less likely we

are to end up in a situation where technology companies are forced to crack open smartphones for even trivial crimes.

Is there anything for those of us in the Apple community to do? In his open letter, Tim Cook isn’t obviously asking for anything other than understanding, but I think we should take the opportunity to make sure our elected representatives are as educated as possible about the danger and futility of intentionally compromised encryption software. That’s because Cook notes that the FBI is using the All Writs Act “rather than asking for legislative action through Congress.” Perhaps I’m reading more into those words than was intended, but if Cook views Congress as a future battleground, the more we communicate with our representatives at all levels of government, the better the eventual legislative tussle will go.

More Thoughts on Apple’s Stance on Backdoors

Apple’s resistance to the FBI’s request for an iPhone hacking tool can be hard to evaluate because the dispute is taking place on three levels: technical, legal, and policy. None of these is necessarily more important than any other, and focusing on just one or two presents a skewed view of what’s going on.

On the technical level, we now know that Apple could do what the FBI wants, but the company is tremendously worried that any such technology would escape into the wild. It’s one thing to create a digital tool, but an entirely different thing to prevent it from being stolen, subverted, or simply copied. Since this tool could subvert the otherwise unbreakable (as least as far as is known) encryption embedded in the iPhone’s Secure Enclave coprocessor, its creation would undermine the privacy of millions of iPhone users.

Because there’s no actual law requiring Apple to comply or, conversely, protecting Apple from such requests, the FBI is relying on the All Writs Act of 1789. That Act has been used in similar surveillance-related cases in the past, but it’s inherently vague, which means that lawyers and judges could wrangle about the specifics for a long time.

When it comes to policy, it seems clear that the FBI is using this high-profile case of domestic terrorism as an opportunity to further its real goal, which is to be able to gain lawful access to evidence from any smartphone or digital device. And while Apple denies that it’s resisting for marketing reasons, given that Apple is a for-profit business, it’s impossible to know how much of its stance stems from being the right thing to do versus being a competitive advantage or marketing point.

I’m coming down on Apple’s side because I don’t believe the FBI understands the technology well enough to appreciate Apple’s argument about the impossibility of keeping a digital genie bottled up. I also don’t see weakening iPhone security as a long-term win, given that it’s far too easy for any interested organization to create, distribute, and use unbreakable encryption software. While I can’t claim sufficient experience to comment on the legal issues, I dislike the way the FBI is using this case to push its agenda, and while Apple sometimes employs its commitment to privacy in ways that aren’t entirely fair to competitors, that’s a far lesser sin.

With all that said, here are the ExtraBITS we’ve published since my original coverage. They paint a fuller picture of what’s happening and are well worth reading if you’re interested in this case.

Google and Microsoft CEOs Back Apple — Twitter doesn’t lend itself to subtlety or nuance, but Google CEO Sundar Pichai used a 5-part tweet to weigh in on Apple CEO Tim Cook’s open letter to customers about the FBI’s request that Apple create a hacking tool to brute force an iPhone passcode in the San Bernardino terrorism case. Pichai essentially signed on to Apple’s position, saying that Google builds secure products and complies with legal orders to hand over data when possible, but simultaneously expressing concern that requiring companies to enable hacking of customer devices and

data could be a troubling precedent. Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella also commented, though less directly, by retweeting a post from Microsoft President and Chief Legal Officer Brad Smith that summarized the firm’s anti-backdoor position via a linked statement from the Reform Government Surveillance group, of which Microsoft is a member.

Tim Cook’s Open Letter Prompted by the FBI Going Public — Apple’s spat with the FBI over building a cracking tool for an iPhone linked to the San Bernardino terrorism case has taken an interesting turn. The New York Times reports that while Apple had asked the FBI to file its request under seal, the government chose instead to make it public. That supports the theory that the FBI is using this high-profile case of domestic terrorism to pressure Apple into compromising the security of its products. Faced with this PR onslaught, Apple saw no choice but

to take its case for supporting encryption to the public in Tim Cook’s open letter. Sadly, this fight between the FBI and Apple could have been avoided had the assailant’s employer used standard mobile device management tools to maintain passcode control over the work iPhone in question.

A Forensics Expert’s View into the FBI’s Request — The more we learn about the Apple/FBI dustup, the more clear it has become that this is actually a subtle and dangerous game of chess. The latest insight comes from Jonathan Zdziarski, considered to be among the world’s leading experts in iOS-related forensics. In a blog post, Zdziarski explains the difference between “lab services” and developing an “instrument.” Apple has provided one-off lab services in the past to help law enforcement recover data when required by law. But developing an instrument is a tremendously involved, verified, documented,

tested, and validated process. It would require significant resources and would result in the hacking tool being made public and usable by any law enforcement or intelligence agency — along with foreign governments and criminal organizations. That’s why Apple is resisting.

Details Emerge in Dispute between Apple and FBI — In a call with reporters, as covered by TechCrunch, Apple executives clarified a couple of points in the ongoing dispute between the company and the FBI. First, any tool that met the FBI’s desire for software that would enable the brute force cracking of an iPhone’s passcode would also work on newer iPhones with iOS 8 or iOS 9 and a Secure Enclave coprocessor. That’s because the data in the Secure Enclave is encrypted by the passcode, which provides access to everything on an iPhone. Second,

the FBI apparently reset the Apple ID password for the account associated with the iPhone right after taking the iPhone into custody. That prevented any further automatic iCloud backups, which Apple could have turned over to the government.

Apple Answers More Questions about FBI Court Order — As speculation swirls about the implications of Apple resisting the FBI’s request for help accessing an iPhone used by one of the assailants in the San Bernardino terrorism case, the company has posted another public statement answering some of the questions that have arisen. In particular, Apple explains why it objects to the government’s court order, whether or not the FBI’s request is technically feasible, why such a technical solution could not be contained, and more. One particular note — despite what has appeared in the media, Apple says it has

never previously unlocked iPhones. Prior to iOS 8, Apple had extracted unencrypted data from locked iPhones for law enforcement, using a technique that didn’t require them to be unlocked. The encryption in iOS 8 and iOS 9 makes that impossible now.

TidBITS Watchlist: Notable Software Updates for 22 February 2016

Mailplane 3.6.2 — Uncomplex has released Mailplane 3.6.2, upping the system requirement for the Gmail-specific email client to OS X 10.10 Yosemite or later. The update also fixes issues with Google Inbox (with the notifier now opening an existing Google Inbox tab instead of Gmail), adds a Reply All button to the separate compose window toolbar, updates WebKit to the same version used in Safari 9.0.3, and switches its update feed to HTTPS. ($24.95 new, free update, 23.1 MB, release notes, 10.10+)

Read/post comments about Mailplane 3.6.2.

Microsoft Office 2016 15.19.1 — Microsoft has issued version 15.19.1 of its Office 2016 suite with some improvements and patches for security vulnerabilities. In Outlook, the release restores the keyboard shortcut for Forward Message (Command+J), ensures the Cancel Meeting command on the ribbon and the Message list filters on the View menu work correctly, and maintains Read or Unread status when a message is moved to another folder. The update also adds more commands to the Quick Access toolbar (such as New, Print, and Save), opens older format files (.doc, .xls, and .ppt) as read-only on NFS

share directories, and retains a Word file’s name when printed to PDF (instead of displaying Untitled.pdf). Although Microsoft doesn’t say mention this, reader Tom Gewecke tells us that the update to Word also includes improvements in support for Hebrew and Arabic. On the security front, Office 2016 15.19.1 patches several memory corruption vulnerabilities that could allow remote code execution. ($149.99 for one-time purchase, free update through Microsoft AutoUpdate, release notes, 10.10+)

Read/post comments about Microsoft Office 2016 15.19.1.

Evernote 6.5 — Evernote has released version 6.5 of its eponymous information management app with a change to using Command-Shift-> and Command-Shift-< to increase or decrease font size, enabling the app to use Command-Shift-+ and Command-Shift– (minus) for a new Zoom feature that’s in beta. If you’ve installed the direct download edition from the Evernote Web site, you can turn on the Zoom feature by going to Preferences > Software Update and selecting Enable Zoom. Additionally, direct download users can access a new Code Block feature, which takes any selected text and converts it to a monospaced font and creates a

gray background around the line of text (turn this on in Preferences > Software Update as well). Users of the Mac App Store edition will have to wait for a later version for both of these beta features.

Evernote 6.5 fixes a bug that prevented checkboxes from printing, resolves an issue where tags with periods or other symbols wouldn’t be found in the tag filter, and improves initial Mac setup performance for accounts with over 1,000 tags. As of this writing, Evernote remains stalled at version 6.4 in the Mac App Store. (Free from Evernote or the Mac App Store, 51.6 MB, release notes, 10.9+)

Read/post comments about Evernote 6.5.

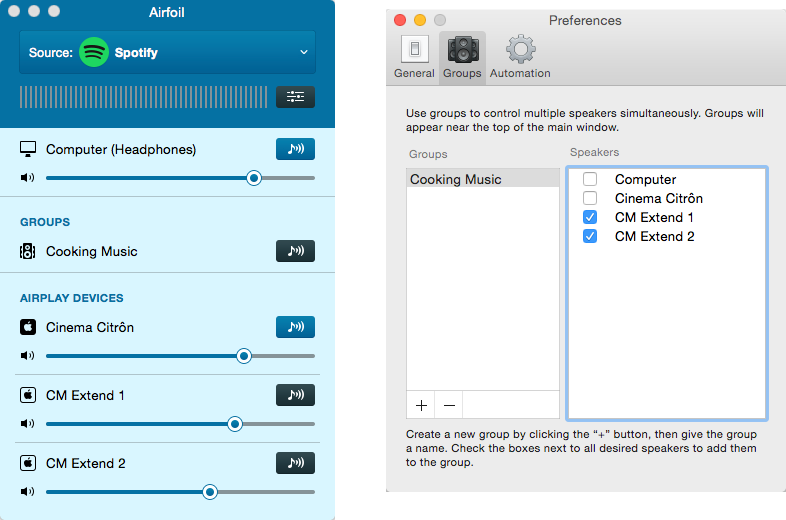

Airfoil 5.0 — Rogue Amoeba has released Airfoil 5.0, a significant update to the wireless audio broadcasting app that brings a number of new features, including support for sending audio to a Bluetooth speaker or headset, as well as to multiple Bluetooth devices simultaneously. In addition to a new and improved user interface with sleeker graphics and longer volume sliders, Airfoil 5.0 also adds the capability to create Speaker Groups (found within Preferences), enabling you to select multiple audio outputs with a single click.

Other new features include a silence monitor (which automatically disconnects Airfoil when it’s streaming silence, freeing up the output device for others to use), adjustable output sync options (found in Speakers > Advanced Speaker Options), and custom equalizer presets. The release also improves the Instant On component and offers full compatibility with Rogue Amoeba’s free range of Airfoil Satellite apps, which enable iOS and Android devices plus Macs and Windows PCs to be used as audio receivers.

Airfoil 5.0 is still priced at $29, and it’s free for those who purchased Airfoil 4 on or after 1 November 2015. For those with an Airfoil 4 license purchased prior to that date, you can upgrade to Airfoil 5.0 for $15. ($29 new with a 20 percent discount for TidBITS members, $15 upgrade, 13.9 MB, release notes, 10.9+)

Read/post comments about Airfoil 5.0.