Photo by Fancycrave

SMS Text Message Login Codes Autofill in iOS 12 and Mojave, but Remain Insecure

Many Web sites and apps now offer two-factor authentication (2FA), which requires you to enter a short numeric code—the so-called second factor—in addition to your username and password. These temporary codes are either sent to you via text message or are generated by an authentication app. In iOS 12 and macOS 10.14 Mojave, Apple has streamlined entering such codes when sent via an SMS text message, reducing multiple steps and keyboard entry to a single tap or click.

I explain just below how this new feature works, but I also want to raise a caution flag. SMS is no longer a reliable way to send a second factor because it’s too easy for even small-time attackers to intercept those messages (see “Facebook Shows Why SMS Isn’t Ideal for Two-Factor Authentication,” 19 February 2018). It’s time for Web sites that use 2FA to move away from SMS.

Passthrough SMS Codes in iOS 12 and Mojave

When you log in to a site with 2FA enabled that offers SMS-based codes, the sequence usually goes like this:

- You complete the standard password-based login and are prompted for a code.

- A text message with a code, typically six digits long, arrives in Messages.

- If you use notifications to show incoming texts and you’re fast enough, you enter the code as you see it into the Web form and submit it. Otherwise, you switch to Messages, either memorize the code or select and copy it, and return to the site to enter it. (In iOS, you can’t easily select part of a message, making that additionally frustrating.)

- Submit the form to login.

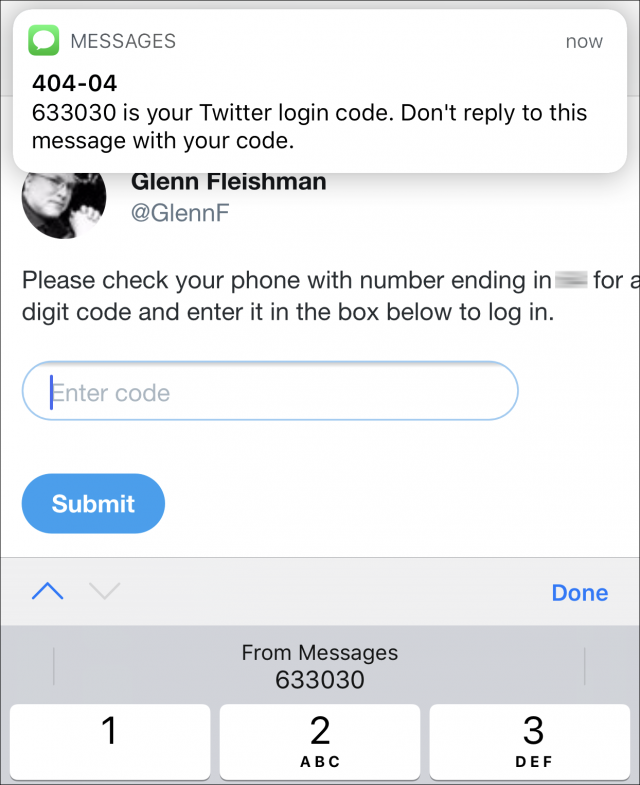

In iOS 12, Safari, Messages, and the QuickType bar above the keyboard work together, in a process that looks like this:

- Enter your username and password as in step 1 above.

- Tap in the second factor field.

- When the text message arrives, iOS 12 extracts the code and displays it in the QuickType bar. Tap it to enter the code in the field.

- Submit the form to log in.

Here’s a quick video demonstration.

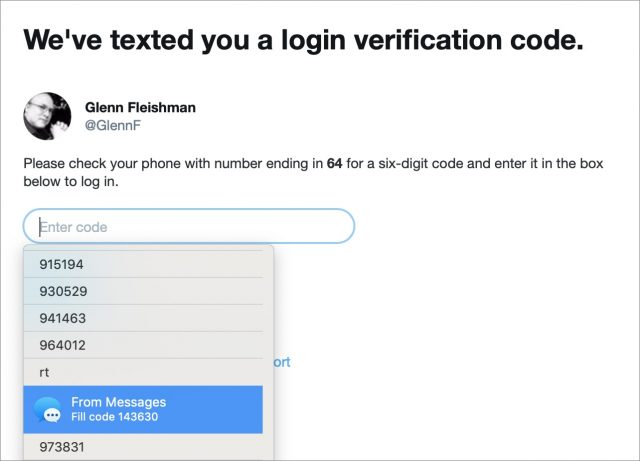

Mojave works almost identically. Instead of the QuickType bar in step 3 above, however, the autofill entry appears below the code field when you click in the field. It’s labeled From Messages and reads Fill Code followed by the short code. Click it to enter it in the field.

Annoyingly, I found that Mojave listed all previous codes texted—in this case, for my Twitter login—and I had to scroll way down in the dropdown list to find the From Messages item. Selecting that item also proved difficult unless I clicked it and then quickly clicked away from the form field. Otherwise, macOS interpreted pointer movement that hovered over the dropdown list as scrolling and selection! Apple needs to refine this user experience and flush previous entries.

These shortcuts shave a few seconds and a little aggravation off the process, so they’re not a major productivity win, but they do make 2FA less of a roadblock for more people. By reducing friction and making it a simple workflow that feels nearly the same as entering a password from the iCloud Keychain, Apple hopes to encourage more of its customers to enable 2FA at more sites.

Unfortunately, there’s a cloud hanging over Apple’s optimism: SMS-based codes aren’t a reliable security method and should have been eliminated over the last few years.

It’s Easy to Hijack SMS Codes

You have probably seen headlines along the lines of, “Cryptocoin investor has entire holdings stolen with account hack!” Such thefts start with an attacker gaining control of a phone number. This is unfortunately surprisingly easy. Mobile phone numbers are portable, which means they can be easily moved from one physical phone to another, and even transferred among carriers. The basic approach works like this:

Step 1: Obtain personal information. “Background check” sites and stolen information floating around the Internet make it trivial to obtain someone’s phone number, Social Security number, bank account number, and other personally identifying details.

Step 2: Hijack a phone number. To take over a phone number, the attacker then generally uses social engineering, another term for scamming someone with words. They call a phone carrier and explain how they need the number transferred, provide the identity information required to verify themselves, and give the technical details for the new receiving phone.

Although major carriers have started letting customers set an additional PIN for account changes, news stories have revealed that hackers have sometimes managed to talk their way around not having the PIN. And since that additional PIN isn’t required, it’s unclear how many subscribers use one.

(Some hijackers have also shown they can insert themselves into the public switched telephone network to sniff information or hijack a phone number. If a lone attacker can do that, governments obviously can as well.)

Step 3: Take over an account with a password reset. Once the attacker can receive text messages for someone’s hijacked number, they can visit a site at which they expect someone has an account and take it over. Many sites that offer 2FA also allow password resets via SMS, making the assumption that physical possession of a phone is sufficient security.

For instance, it’s common to see text like this on a password reset page:

If you don’t have access to the email address on file for your account and need to reset your password, you can use your verified phone number to update the email address that receives the password reset email.

At many sites, the attacker would also need to know the original email address, which is trivial for someone who has hijacked a phone number.

Thus, an attacker requests an email address change and receives a link via SMS to complete it. On that page, they provide the new, illegitimate address, and verify its receipt to finish associating the account with the new email address. Then they can complete a password change, which sends a link via email to the new address, and with the new password set, they can log in—using the SMS code for 2FA.

Each of these steps is benign, but it all adds up to effectively requiring just one credential—the phone number—instead of two.

With full access to an account, the attacker can drain cryptocurrency, send out email, and carry out other financially or reputationally damaging attacks.

It’s Time to Stop Using SMS for 2FA

Sites originally chose to use SMS-based code validation for 2FA to lower the barriers to 2FA—more people understand SMS than authentication apps. And, regardless of the vulnerabilities of SMS, it’s far better to use a second factor than not, because it deters wholesale attacks against accounts. Even if an attacker gained access to all the decrypted passwords for a service, every account with 2FA enabled would still be able to resist unauthorized logins. But SMS-based 2FA is vulnerable to targeted attacks and identity theft.

Apple’s proprietary 2FA system for macOS and iOS remains extremely robust, but it still allows the use of SMS and voice calls as a backup when trusted devices aren’t available. Many other systems rely on authentication apps that generate time-based one-time passwords (TOTPs), including 1Password, Authy, Google Authenticator, and LastPass, among others. When you use this app-based approach, a service typically also issues you emergency one-time use backup codes that are static—they don’t expire over time, like TOTPs.

Despite Facebook’s routine hiding of new policies that are invasive of people’s privacy and personal information, the company does allow you to use 2FA without a phone number. (This is more significant now that researchers have discovered Facebook has been exploiting people’s 2FA-associated phone numbers for marketing purposes.) Google doesn’t make this fact explicit, but after setting up 2FA, you can remove phone numbers, too, and rely on a combination of other second factors.

While it’s admirable Apple has streamlined SMS code entry, it would be even more so if the company would kickstart the move away from SMS. Such a move doesn’t have to be forced: it could begin with Apple and others providing education and offering a switch to disable SMS codes as backups. It’s inevitable that we’ll have to stop using SMS-based 2FA codes, and it would be better to work toward that before a wide-scale hack makes it a crisis.

If you’d like to learn more about managing security features in iOS 12, as well as understanding and configuring networking and privacy, check out my new book, “A Practical Guide to Networking, Privacy, and Security in iOS 12.” TidBITS readers get 25% off with the coupon code TIDBITS.

I’m not sure I understand why we should give up on using text message 2FA because of phone number porting. Shouldn’t the proper response to the issue be that carriers are forced to ensure that I and only I can authorize them to move my phone number to another SIM or device? I would expect the carrier to be responsible for safeguarding my number since they are the only party who can do that. If they aren’t willing to do that, why should I be doing business with them in the first place?

Any system that relies on human frailty will fail.

The answer is yes, the carriers should secure us from SIM hijacking, but they remain imperfect. What remains nearly impossible to hijack (if not impossible) is time-based one time passwords (TOTP), such as delivered by an applications like Google Authenticator or Authy, or even the method used by Apple with their devices, which delivers these messages to all devices using the Apple ID to approve a new login.

Here is a recent article detailing how easy it is to be SIM-hijacked: https://motherboard.vice.com/en_us/article/vbqax3/hackers-sim-swapping-steal-phone-numbers-instagram-bitcoin (and I apologize if this has been linked before.)

Plus the accompanying “what we can do to protect ourselves”: https://motherboard.vice.com/en_us/article/zm8a9y/how-to-protect-yourself-from-sim-swapping-hacks

Phone companies are supposed to ensure that you are the person authorizing them to move your phone number to another SIM. But in reality this doesn’t happen often enough. The customer support people end up doing the move in the name of customer support. There is no reason to believe that the phone companies will get any better at it.

There is a big difference between “should” and “does.”

Yeah, I was being facile above, but that’s it. There’s no sensible way to use SMS reliably, because both the telephone switching system (SS7) used globally cannot be properly secured (allowing hacking and interception), and the way in which user accounts and phone portability has been designed prevents creating a process with enough identity integrity that it won’t frustrate average people who won’t be able to reliably cross the security bar.

Using an authentication app or Apple’s 2FA ecosystem makes vastly more sense if you actually want the extra security. SMS is more secure than single-factor password logins, but not secure enough as a continued path forward.

And if they make it harder, customers get frustrated and shift carriers — and they also add to the cost and burden of customer service. It’s a no-win situation. 2FA wasn’t designed to work over an insecure medium like SMS in the first place, which is why it’s not a good idea now.

So are providers who choose to have their customer service reps put convenience over security not getting sued big time when somebody gets defrauded of hundreds of thousands of $ and/or falls victim to identity theft with serious consequences?

I have to admit I have a hard time seeing how using a myriad of apps should offer better security. How many apps have had security issues? How many businesses (who issue these apps) have been hacked? How many app “stores” have suffered form hacking? iOS might be one thing, but what about the large rest of the world? On another note, how is using a plethora of apps to essentially do one thing (2FA) convenient? I don’t think a world where every online account I have also requires me to download some app that I essentially have to trust blindly is such a great perspective.

I guess I’m just asking a whole bunch of naive questions because the more I hear about the issue the more I wonder if 2FA was such a great idea to start out with. That said, it also sounds like a somewhat regional issue. Identity theft seems to be especially rampant in the US (compared to several western European countries I know). From what I gather perhaps because companies here are not really held to especially high standards when it comes to safeguarding their customers’ data and privacy.

The carriers have seemingly negotiated away some liability through disclaimers and disclosures, as I haven’t yet heard of a successful lawsuit. (They may make private settlements and force NDAs to avoid them.)

2FA is a great principle, and SMS isn’t technically a second factor by a lot of definitions. A second factor has to be disconnected from the first. It’s also not a myriad of apps. There are only a few apps that offer TOTPs that people recommend (Authenticator, Authy, Duo Security, and 1Password), and the other apps used for verification are made by the service provider (Facebook, Google, etc.), which has some liability and responsibility.

SMS was convenient, not the right choice.

It gets reported more here, but I cannot believe there’s less of it. A lot of the reporting in Europe will be in non-English languages, reflecting the majority of residents’ native tongues, so likely to be less visible than, say, identity theft in the UK, which is as much of a problem as in America.

While I would argue that TOTP apps like Google Authenticator are a bit tech-heavy to explain to average non-technical user, it surely doesn’t require having a security app for each app that you own. Not only does a single instance of Google Authenticator/Authy work with online services from Google, Facebook, Dropbox, Twitter, Instagram, Amazon, Microsoft (and many others), now 1Password supports storing these TOTP codes for you, and can fill them as well as user ID and password for you. (One might argue that using 1Password to do this is putting all of your eggs in one basket, though.)

Google Authenticator’s great weakness is that there is no way to restore the codes, such as when you buy a new phone are restore from backup. Authy does offer a password-secured cloud backup of these codes, though.

A good, though old, article from TidBits about such a scenario (though the info about Apple is out of date): Dancing the Two-Step: Coping with the Loss of a Second Factor - TidBITS

And an articles about getting started with 2FA using an app like Google Authenticator: How to Secure Your Accounts With Better Two-Factor Authentication | WIRED

And there is one other method not already mentioned: using a security key made by a company like Yubikey.

Apple does have a two factor authentication system that handles the security issues that SMS two factor authentication has.

I wonder if it’s possible to open up to third parties. Not a fan of Google’s effort because they take so much effort.

Noted in the article, but it falls back to SMS (or a voice call).

Yes, but Apple’s two factor authentication system isn’t available to other developers. Apple could open it up to them. If they did, then they’d have a secure and simple way of doing two factor authentication.

The fallback to text or voice call does cause security concerns. However, if for some reason you cannot do two factor authentication the secured way, what should the system do? Lock you out entirely? Maybe there could be a more secure way. Facebook allows you to choose five people who can vouch for you.

I was thinking about why Apple doesn’t open their 2FA system up, but my suspicion is that if they let other developers use it, it would be much more likely to be exploited.

Most authentication app systems let you print out emergency codes; Apple could do something similar, although I think they’d probably go for a system that would rely on biometric information stored in the Secure Enclave if they could.

Apple could easily offer an authentication app for Android and Windows that could produce a location alert and code securely and very much like the baked-in versions in iOS and macOS, but perhaps would require launching the app and authenticating it, instead of providing a notification popup.

I just don’t think Apple has a motivation to do so.

A different but important problem with SMS based (or other phone based) 2FA is the fact that some users (as myself) access sites using different SIM cards (& phone#) while they travel. This --in addition to the fact that SMS services may not be reliably available in parts of the world-- practically eliminate 2FA with phone based second factor for most applications. Some banking services in Europe offer a physical “dongle” that generate a time-limited one time code, but physical objects have their own vulnerabilities (stolen/lost) and how many of these items one have to carry? Time for a better solution (IMHO)

A better solution exists: Time-based (not message-based )Google Authenticator codes via an application like Authy. See this article from a few years ago on Tidbits: https://tidbits.com/2014/11/06/authy-protects-your-two-factor-authentication-tokens/.

I have used Authy for several years, with it installed on my phone, tablet and watch.

Noted in the article! App-based authentication can be effectively tied to a device — its internal tokens can’t just be copied elsewhere and used — so it meets the “something you have” requirement fairly well. I’m a big Authy fan.

The very best solution is U2F (universal two factor), which requires a physical dongles and uses public-key cryptography to identify a user uniquely to a service and to let the user validate that the service requesting a code is the one they signed up for. You first enroll, and the service holds your public key. So the next time you log in, the service sends something that’s signed with your public key. If you don’t get a properly signed message, you know it’s a phishing site, not the real one. A great layer on top of https.

However, in practice, I don’t know when and how it will be widely adopted. Yubikey makes a bunch of these U2F dongles, and they’re supported in macOS via Chrome, as well as more deeply elsewhere. Because it requires a physical connection, it’s a problem with mobile devices, and you have to carry your U2F device (however tiny) around.

My suspicion is that a mobile phone could embed a U2F-like system into Secure Enclave or a similar secure area, and provide generic 2FA validation that’s completely device locked and uses the protocol effectively.

One of the advantages with U2F on services that don’t offer fallback (it’s U2F or a backup one-time code or nothing) is that the password can be super simple—like a 4-digit or 6-digit code. Because there’s no value at all in breaking the password.

The dongle my bank gave me back when I lived in Sweden didn’t require a physical connection at all. It required I insert my debit card and then punch in my passcode as well as a one-time passcode they displayed on their website while I was logging in. The dongle then gave me an answer passcode that I punched into their website. Done. This actually worked even on iPhone Safari, no cable connection whatsoever. It might sound a bit cumbersome and the disadvantage is of course that you need that dongle on you, but I suspect it was top notch in terms of security and it always worked very well for me.

Yes, that’s a hardware TOTP generator. It qualifies as something you have because it is locked to hardware you have to possess.

Glenn, couldn’t something like that be used by 3rd parties instead of SMS for 2FA?

It has been for years, but the devices gradually became replaced with authentication apps, which are more or less as secure, because the use of the token is tied to the app as installed on a specific hardware device. You can’t move the app or its data to another device and have it work, as opposed to a phone number.

I had a couple of hardware TOTP dongles for E*Trade and PayPal for many years (I think one had to be replaced), before companies switched to authentication apps and SMS.

My suggestion, echoing security experts who understand the details better than I do, is that SMS be slowly phased out, and that existing services that allow SMS fallback provide an option for sophisticated users to disable SMS. So for Apple users, you’d rely entirely on trusted devices. But Apple would have to create one-time use backup codes, too, which they don’t offer now.

The other issue with those dongles is that it was infrequent when you could use one with multiple services, so you could envision carrying multiple dongles with you. That’s definitely an advantage of Google Authenticator based TOTP apps, which deliver the codes to apps on the phone or tablet, though many more services are now supporting the YubiKey devices that Glenn mentioned earlier.

I’m not at all convinced apps are a good replacement for dedicated hardware. I am also not convinced that trying to have everything on one phone and accessed through one app (such as Google Authenticator) is a good idea. Just look what happens each time Google or Facebook get hacked and people realize they used Google or FB to authenticate with all kinds of other businesses.

I realize the convenient solution is one app on your one phone with you at all time and accessed by just glancing at the FaceID camera. That kind of convenience, however, appears to come with a security penalty. I’m not ready to believe there’s a free lunch here.

An issue with hardware dongle authenticators is that there is no universal peripheral connector on Internet capable devices. For example, my 3-year old desktop has only USB3 and Thunderbolt 2, my 3-month old laptop has only USB-C/Thunderbolt 3, and my IOS devices have only Lightning. So for all but one device, you end up needing to use another dongle to interface to your hardware dongle.

As I already wrote above, the dongle I used a couple years ago never required any kind of tether, wired or wireless. The only standard it relied on was my eyes and my fingers. I’d argue that’s a rather global standard.

Definitely a key problem. I have an iMac, and I got a Yubikey with USB-C—then realized I a) don’t want to occupy a port all the time with it, as I only have four USB-C ports, and b) it’s hard to reach (as you have to press it) behind my iMac!

Yes, Alan is talking about the new U2F and similar authenticators. The kind you’re talking about are many years old and have been widely used in government, commerce, and sometimes in consumer finance.

Google’s entry into the U2F field (the Titan Security Key) comes in USB and Bluetooth flavors. (Last time I looked, it appeared that you had to buy one of each. I’m not sure how close Bluetooth comes to “universal” these days, but it has to be more widely available than any given single wired connector.

–Ron