How a Passcode Thief Can Lock You Out of Your iCloud Account, Possibly Permanently

Tech reporters Nicole Nguyen and Joanna Stern of the Wall Street Journal are back with a follow-up on their exposé of Apple’s problematic iPhone security design decisions. In the first article, they showed how a shoulder-surfing thief could discover a user’s passcode, steal their iPhone, and change their Apple ID password to disable Find My before making purchases with Apple Pay, accessing passwords in iCloud Keychain, and scanning through Photos for pictures to aid in identity theft (see “How a Thief with Your iPhone Passcode Can Ruin Your Digital Life,” 26 February 2023).

In another article (paywalled) and accompanying video, Nguyen and Stern now explore the ramifications of what happens when a passcode thief changes the user’s Apple ID recovery key, which is again doable with nothing more than the iPhone passcode. In short, the thief can lock the victim out of their iCloud account, possibly permanently, preventing access to precious photos and more. Apple has responded sympathetically but hasn’t helped—or been able to help—users get back into their accounts.

One Recovery Key to Rule Them All

The problem is that once the thief sets or resets a recovery key, it becomes the only way to regain access to an Apple ID account once the password has been lost—Apple says it can no longer help through its usual account recovery process. Apple is clear about how creating a recovery key puts additional responsibility on the user, but that’s an acceptable trade-off for a technically savvy, organized user.

What’s not acceptable is allowing a thief with nothing more than a stolen iPhone’s passcode to set or reset a recovery key. That creates a situation where a user becomes vulnerable to their account being locked even if they had no intention of setting a recovery key or were already managing it securely. The article says:

After Cameron Devine’s iPhone 13 Pro was stolen from a Boston bar in August, the 24-year-old said he spent hours on the phone with Apple customer support trying to regain access to over a decade of data. Each representative told him the same thing: No recovery key, no access. Mr. Devine said he had never heard of the key, let alone set one up.

The article does give another example of a person for whom Apple was able to disable the recovery key, allowing the user to regain access to the account. Although Apple declined to comment on that situation, the user reportedly used some Apple “business services,” suggesting that his iPhone might have been enrolled in device management and thus different from a regular user’s iPhone.

Although I haven’t been able to find a detailed explanation of how the recovery key works in Apple’s Platform Security Guide, my understanding is that it essentially acts as a second copy of a user-managed encryption key that takes over from Apple’s usual account recovery option.

To enable end-to-end encryption, such as with Apple’s Advanced Data Protection for iCloud, the user must generate and maintain the encryption keys (see “Apple’s Advanced Data Protection Gives You More Keys to iCloud Data,” 8 December 2022). In the Apple world, those keys are generated automatically and stored in the Secure Enclave, and to protect against their loss, Apple requires that anyone turning on Advanced Data Protection specify account recovery contacts or set a recovery key. That’s necessary because Apple doesn’t control the encryption keys and thus can’t help a user get into an account if the password has been lost or reset by a thief.

What Apple Can Do to Address This Vulnerability

If my understanding is correct, Apple is not being disingenuous or obstructionist when it comes to helping people who have suffered a passcode and iPhone theft. Once that recovery key is set, the company can do nothing to help—it no longer controls the necessary encryption keys. That’s why I say that users may be locked out of their accounts permanently.

When the Wall Street Journal article talks about how victims attempt to prove ownership of their accounts with various forms of identification, it’s missing the point—identification is not in question; the data is simply inaccessible because it’s encrypted with a key that Apple doesn’t control.

The ultimate fix comes down to reducing the power of the passcode. We’re constantly told that we must create strong, unique passwords, and yet the most important device in many people’s lives is locked with nothing more than a six-digit passcode. Apple could protect users against the more severe ramifications of passcode theft by requiring additional authentication—perhaps using Face ID or Touch ID without the passcode as a fallback—before allowing someone to reset the Apple ID password or recovery key option.

Saying that is easy, but I’m fully aware that many devils dance in the details. Apple is walking a fine line between strong security and being able to help users who lose access to their accounts. Apple might be weighing the risks to the relatively few people whose passcodes and iPhones are stolen against the problems faced by numerous unsophisticated users who forget their Apple ID passwords and have no other Apple devices. Then again, Apple is willing to inconvenience everyone with frequent security updates for vulnerabilities that might be used against only a few high-value targets. Security is always a balancing act.

What You Can Do to Protect Yourself

For the most part, my advice surrounding passcode protection hasn’t changed from my previous article. In “How a Thief with Your iPhone Passcode Can Ruin Your Digital Life,” I wrote that you should:

- Pay attention to your iPhone’s physical security in public.

- Always use Face ID or Touch ID in public.

- If you must use your passcode in public, conceal it from anyone nearby.

- Never share your passcode beyond highly trusted family members.

Creating a longer alphanumeric passcode, as Nguyen and Stern suggest, could help, but only if it’s sufficiently long and complex that a shoulder surfer wouldn’t be able to memorize it. However, such a person could surreptitiously record you entering it and then refer to the video after stealing your iPhone. They might be more obvious while recording, but you would be less aware of your surroundings as you tap in the complex passcode. And none of this would protect against the threat of physical harm unless you reveal your passcode.

The best protection right now is to use Screen Time, as I discussed in my previous article. If you enable Screen Time, set a separate four-digit Screen Time passcode, navigate into Content & Privacy Restrictions, and select Account Changes > Don’t Allow, thieves can’t easily change your Apple ID password or recovery key options without that passcode.

Unfortunately, the Screen Time passcode does that by preventing anyone, including you, from entering Settings > Your Name to make changes without first going to Settings > Screen Time > Content & Privacy Restrictions > Account Changes > Screen Time Passcode > Allow. You’d also need to set that option back to Don’t Allow once you’re done. If Apple tweaked iOS 17 to prompt for the Screen Time passcode as a secondary security check when accessing the blocked options, it would be much easier to recommend.

More problematically, I believe it’s possible to reset the Apple ID password during the process of disabling the Screen Time passcode, thus bypassing Screen Time’s restriction on account changes. Apple reportedly addressed some of this vulnerability in iOS 16.4.1, but I was still able to change my Apple ID password knowing nothing beyond the passcode. My testing wasn’t as complete as I would have liked because I risked locking my Apple ID account for days, but Apple definitely has more work to do here.

There is one final thing you can do to protect your data: make local backups of everything stored in iCloud. Most of the users who lost access to their iCloud accounts were particularly distraught about losing their photos, which is understandable but easily avoidable.

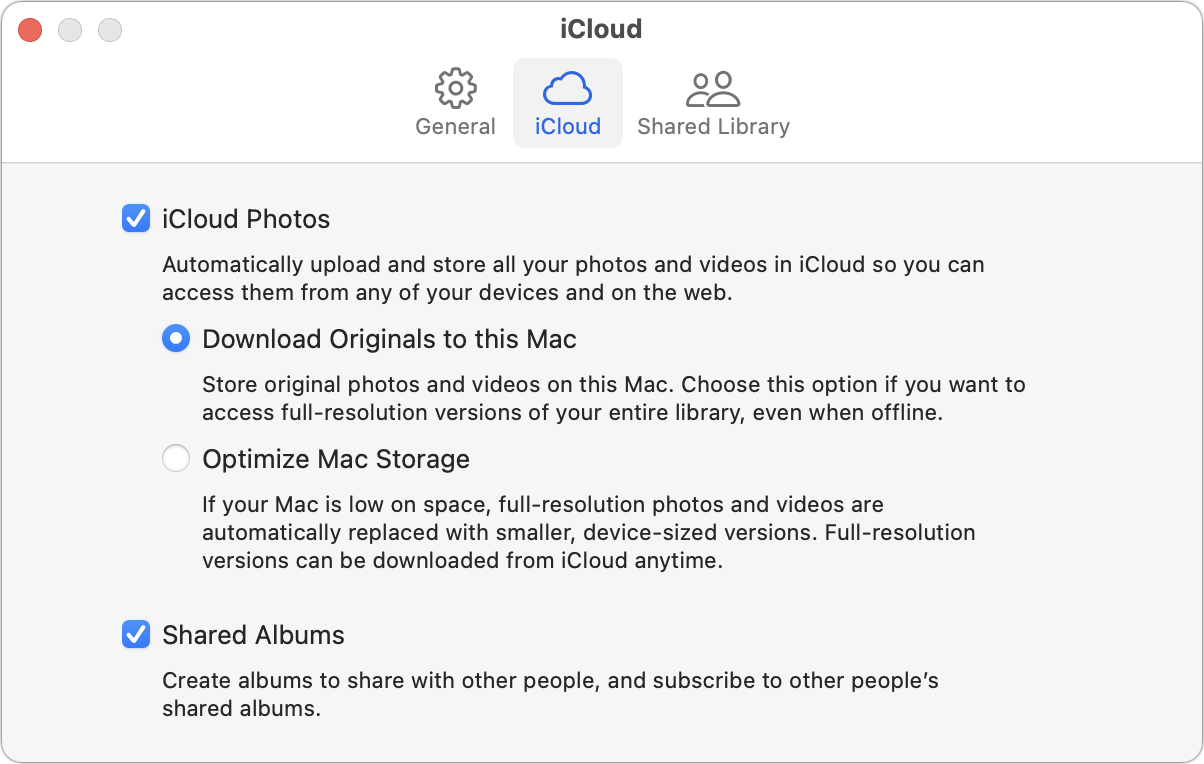

Set Photos on a Mac to download originals, and then make sure that those original images are included in your backup strategy, which should include at least Time Machine and an offsite backup, and preferably also a bootable duplicate. You’ll need sufficient free space for them all; if that’s a problem, you can relocate your Photos Library to an external hard drive.

This backup won’t keep the photos out of the hands of a thief who has taken over your account, but at least you won’t lose your images.

Stay safe out there.

This purports to use Screen Time to prevent this from happening. Will that work (I don’t use Screen Time)

Yes, I explain the Screen Time approach in the article, and explain why I think it’s annoying: you can’t do anything in Settings > Your Name unless you jump through a six-step process to disable the setting and similar process to reenable it.

[edit: the below is now fixed with 16.4 and later.]

It doesn’t work though. If the thief knows the passcode and the Apple ID (discoverable in a few areas of the Settings app, or just by looking at the email accounts set up on the phone), they can change the Apple ID password, bypassing the screen time restriction, and then add a recovery key. I wish Joanna Stern would stop recommending that as a solution.Is that true if you don’t make the Screen Time passcode recoverable with the Apple ID, though? If you have a separate Screen Time passcode that can’t be reset without knowing what it is, it should work for preventing access to the account settings.

OK, I have to recant what I just said, and I’ll go update the article. The Screen Time passcode is always vulnerable to being turned off by someone who knows the Apple ID password. I verified this by creating a Screen Time passcode and explicitly skipping the step that claims to provide Apple ID recovery.

Then I tapped Change Screen Time Passcode > Turn Off Screen Time Passcode. That asks for the passcode, which a thief wouldn’t know, but there’s a Forgot Passcode? link at the bottom of the screen. Tap that and you’re prompted for your Apple ID and password, and once you enter them, the Screen Time passcode is deleted.

I consider this a serious bug in Screen Time, not to mention overall iOS security.

Wait a second! I’ve gotten mixed up about the chronology of events here.

The thief has stolen the passcode and the iPhone, but when they attempt to change the Apple ID password, the Screen Time passcode will block them from accessing the account settings. And since they don’t know the Apple ID password, they can’t use it to turn off the Screen Time passcode.

So I’m recanting my recanting and restoring my original text in the article.

Augh! The plot continues to thicken. You’re a thief with a stolen iPhone and its passcode. But there’s a Screen Time passcode preventing you from changing the Apple ID password. I think, but I haven’t confirmed for sure, that there may still be a workaround.

What I wrote above about turning off the Screen Time passcode is still accurate, but if you don’t know the Apple ID password, Apple helpfully provides another Forgot Apple ID or Password link. Tap that and you get into the flow of resetting the Apple ID password, which I think you can do if you know the iPhone’s passcode as long as the user hasn’t set up a recovery key. I had done that, so at some point, I was asked for my recovery key, and there’s no way a thief would know that.

So the combination of a Screen Time passcode and a recovery key should be full protection. Back to the article! I hope you’re all enjoying watching this in real time.

As it turns out, Apple fixed this with 16.4, at least if you have a trusted phone number and more than one trusted device. It used to be you could do a certain set of actions that would allow you to change the password even with the screen time passcode block (I won’t list them.) But with 16.4 Apple now requires you to confirm a trusted phone number, and then requires you to use another trusted device to actually change the password.

Ok, as I said I’ve avoided typing out the actual steps, but that’s what they were. Prior to

16.416.4.1, if you went through that procedure, it didn’t ask for the recovery key (or a trusted phone number) - it just let you change the Apple ID password. At the time Joanna Stern published her original article, that vulnerability existed. It still does I suspect if you are on iOS older than16.416.4.1.Thanks, I’ll have to test this all the way through—I am running 16.4.1.

For me, even if setting up a Screen Time passcode isn’t an impregnable defense, doing so is a good idea becaue it could buy me enough time to wipe my phone before a thief figured out how to bypass the passcode.

Adam

Do I recall correctly that this problem would disappear if Apple required that you enter the current Apple ID password before you can change it?

Norbert

Quick correction: this change happened in 16.4.1. I have a device with 16.4 and verified that I could change the Apple ID password with a screen time passcode restriction on the account knowing only the Apple ID itself and the device passcode. So, this was an undocumented change in 16.4.1.

Precisely my logic with the additional thought that if it might be too much hassle for them, they may choose to just discard.

OK, I just spent a bunch of time testing this carefully, and while it may be better, it’s not fixed.

Let’s assuming the thief has your iPhone and your passcode, but you’ve turned on a Screen Time passcode and locked account changes but not set a recovery key. The thief can find your email address and phone number from email and Settings > Phone.

Then, if they work through the steps to turn off the Screen Time passcode, saying Forgot Passcode when prompted, entering your email address when prompted, and then tapping Forgot Apple ID or Password, they’ll be able to reset the Apple ID password using just the passcode and turn off the Screen Time password in the same step.

The confusion, I think, is that there’s a branch in the logic at one point, and if they follow the other branch, they’ll be prompted for your trusted phone number or recovery key. The problem occurs at the Screen Time Passcode Recovery screen:

If they enter your email address in the Apple ID field here, tap OK, and then get the password field, they can then tap Forgot Apple ID or Password and continue with the passcode to reset the password. In other words, the most obvious approach is the least secure.

If, instead of entering your email address right away, they tap Forgot Apple ID or Password first, and then enter the email address, they’ll go into the more secure password reset flow that tells them to continue on your other Apple devices. If they say they can’t get to them, they’ll be asked for your trusted phone number, which they can find out easily. But that doesn’t end up working out, at least in my testing.

When I entered that, I was prompted for the passcode again, but entering it threw me to the Don’t Know Your Passcode screen that was warning my account would be locked for several days. At that point, I bailed—who knows what would happen if I locked my account like this. But I very much got the sense that a thief wouldn’t be able to change the password that way.

I’m being a little waffly here because I only tested a few times—I was just too leery of locking my account or messing something else up entirely. But I’ll report this to Apple and see if anything comes back.

All that said, if you both turn on the Screen Time passcode and set a recovery key, you’re safe. There’s no way to turn off the Screen Time passcode without having access to the recovery key.

That seems incorrect in my case. I have both a recovery key set and a screen time passcode and I can still go through and change the Apple ID password with the procedure you listed. (I just, in fact, actually changed it - and very shortly afterward realized that this meant that my Sonos stopped playing music because I had to reauthorize my Apple Music account.)

Having a screen time passcode with account changes disallowed makes it harder to find the Apple ID address on the device, but not impossible.

Darn it, I think you’re right. That was my starting condition, and when I assumed it worked, it was before I discovered that there was a difference with when you enter the email address in the Screen Time Passcode Recovery screen. I have screenshots showing that the recovery key is required, but I’m pretty sure that’s in the branch where you enter the email address AFTER tapping Forgot Apple ID or Password.

I’ve set up to replicate now, and while I don’t actually want to change my Apple ID password again (it invalidates my app-specific passwords and causes all sorts of cascading alerts on different devices), I’m getting the screen to change the Apple ID password without being prompted for the recovery key first.

Any ideas about how to backup your iPhone photos if you don’t have a Mac?

I’m sure there will be other suggestions, but iMazing is cross-platform and gives you a lot of control over backing up and configuring iOS devices.

On a Windows PC, you are expected to install iTunes and use it for all of your iPhone backup/sync operations: Transfer photos and videos from your iPhone or iPad to your Mac or PC - Apple Support

To get iTunes, go to https://www.apple.com/itunes/ . If you’re on a Mac, that page presents you with a request to upgrade macOS, but there is a link to click on to get to the download page for the Windows version:

Windows users can also install it from the Microsoft Store.

Well, of course iCloud Backup also backs up photos whenever the device backs up, unless you have iCloud Photo Library turned on. In that case you can sync with Windows computers using Apple’s iCloud for Windows.

Online cloud file sync service apps like Dropbox also offer to sync your photos to their services, but IIRC when I tried this, it wasn’t the most reliable sync.

Let me restate: Any ideas about how to backup your iPhone photos if you don’t own any sort of (traditional, Mac or PC) computer?

Obviously iCloud is not a solution if the issue is that you have been locked out.

So far Dropbox has been proposed but not as a reliable solution.

Picture Keeper is a flash drive / app that lets you export your photos; the flash drive has a lightning end and a USB end. https://picturekeeper.com/

I’ve used this when I’ve been on vacation on a small cruise ship that had internet connectivity occasionally, but blocked iCloud sync when it did. It worked pretty well.

I think the issue raised regarding Dropbox’s “reliability” for iPhone photo backup involves background uploading, and this would apply to any non-Apple piece of software.

In short, Apple does not allow third party apps to run indefinitely in the background. Third party apps can request temporary “background” access to resources from iOS, but it is almost impossible to predict exactly when iOS will grant such access and the duration of that access. In part, this is intended to prevent apps from draining the battery or taking too much bandwidth without the user being aware of it, especially when resources are low.

I do use Dropbox to make an independent copy of my photos to the Dropbox cloud. I consider it a valuable part of my personal data protection strategy. I’ve gotten into the habit of opening Dropbox on my iPhone once a day or so. When it is opened, any photos that have not automatically uploaded to Dropbox “in the background” will start uploading immediately. It’s not perfect, but it is significantly better than nothing. No Mac or PC required.

Sure wish this had come out last week!

An additional way they accessed my account. They bought a new iPhone, used my Apple ID, changed the phone numbering proceeded to drain accounts. They took over $30,000 before all the banks locked my accounts, even though I called them the night it happened. The also made significant purchases from Best Buy, using two different banks.It took 5 days of calls with Apple support to finally get a Senior Advisor who tried all the normal actions to get my account back.

After all failed, she said that she could block the account, keeping them out of the account as well. Hopefully that worked.

Now the hard part is trying to establish a new account. To delete all the devices in your account, you must fill out a form for each device, using the serial number and the DATE OF PURCHASE! Who keeps that with their serial numbers? To get them from Apple, you must take your device into the store to have proof that you own them. Now I have to take in 3 iMacs and 3 iPads back to the Apple Store before I can begin rebuilding my devices. On top of this, I can find no way to get Apple to credit me with all the Applications I have bought. I have been an Apple since 1978 when I bought the first iMac SE, am a minor investor and get no joy from the company.

Final tip is lock all ATM and Debit cards. Unlock when you use it, then lock it back up immediately.

Another issue is that using my iMac, we were unable to get to the Recovery Key input area. Must have tried over 20 time to get to the location that the Apple instruction say to use (while screen sharing with apple) and there was no way to input the data. What’s the point of have a Recovery Key if its worthless.

Guess Apple needs to fix this then…but in reality I’m not sure it’s a serious problem since if you have any recent iPhone it’s got biometric ID of some sort…I get asked maybe once a week for my passcode by mine and it’s never happened that I recall away from home because that’s where I am the most. Still…it would be good to have a guaranteed method just in case…more security is usually better…at least up to a point.

Yeah, this is a pretty targeted attack, but the number of people that the Wall Street Journal has identified as falling victim to it suggests to me that a non-trivial percentage of iPhone users are either not using the biometrics or are having trouble with them, such that they enter their passcodes frequently. I actually audited my iPhone use for a week and confirmed that I was asked only once for the passcode, which jives with Apple’s claims that it will happen every 6.5 days regardless. I even have a friend who refuses to use Face ID because he think it’s sharing his facial features with Apple. I couldn’t convince him that he was wrong and that Face ID is far safer than tapping in the passcode repeatedly. Even after the WSJ article came out.

I’m so sorry to hear about this, @opiecook! Do you have a sense of how the thief got your Apple ID password? (From the way you describe it, it doesn’t sound like they stole your existing iPhone and passcode.)

The best I can figure out is that we had been in Oakland area for a wedding couple of weeks ago. My iPad was left in my room, with finger ID security. However the hotel had my email account, my phone number and my address. Either that was enough for the scammer to order a new phone on my account or they had a device that could copy my locked device. There is no way they could have figured out my Apple password, as it was a sequence of unreadable letters and numbers.

I have been on the phone with Apple and various credit card companies constantly since the 18th and it’s not over yet. They are trying to use Zelle and I finally got that locked. I did get good news yesterday. Schwab was able to stop all the money transfers they attempted. I’m now at a point I I want to know what’s on any of my accounts, I have to call in, as I have blocked all on-line access to my accounts.

BTW I have sent your article to almost everyone I know. Thanks for publishing, as it wasn’t early enough for me but I don’t want anyone else to encounter the same issue. I still haven’t gotten my computer back to where I can use it properly.

Adobe has a cloud storage option for photos in their ecosystem. If you have or get Lightroom CC, you can download the iOS app and give it access to your iPhone photos, which will then be copied into Adobe’s cloud.

This of course requires buying into Adobe’s ecosystem, but it might be worth it, depending on your situation. I’ve found it to be fairly reliable. YMMV.

One reason may be what I’ve experienced ever since I first bought a biometrics enabled Apple device: it has never accepted my fingerprint for Touch ID. It accepted the setup of that feature, but every time I’ve attempted to use it, it refuses to recognize my fingerprint. I’ve deleted its database and started the setup from scratch many times. Although it claims the set up is satisfactorily completed and working great, it still won’t recognize my “touch”. So I’ve just given up on it.

I also have a great deal of trouble getting an iPhone screen to accept swipes. I’m guessing my fingertips are just too calloused to get the devices to recognize my attempts at input.

Could the iPad’s screen have revealed your passcode with smudges?

Otherwise, there could be an interesting vulnerability related to a new iPhone being able to be added to an Apple account if email and phone number are known. I can’t quite imagine how that would work, but that’s not to say there isn’t some sort of hole in the process.

I don’t use a passcode on it, it has finger print verification. I agree that using the new phone attack seems very unusual, but unless there was someone on the inside that was working with them, I can not think of how this was accomplished. All I can say, is I wouldn’t wish this on my worst enemy.

I, obviously, only know what has been posted here about the attack. But my guess is that the account takeover was made possible through phishing, either online or through a phone call, and/or SIM swapping. The timing of the hotel stay may simply be a coincidence.

In any case, the overall situation is horrifying and I hope @opiecook is able to get everything sorted out and fixed soon.

Is it possible they pulled the sim and duplicated it? I never even thought of that possibility.

It’s impossible not to have a passcode, and even if you use Touch ID, you’ll be prompted for your passcode every so often.

Not inconceivable, I suppose, but the SIM only defines your cellular plan and is unrelated to the overall device security.

Some sort of phishing attack could be related—if the user can be fooled into entering their Apple ID password into a malicious Web page, that’s a major problem. In theory, there should be additional checks (@opiecook, do you have two-factor authentication turned on for your Apple ID?).

Maybe but SIM swapping more often involves either the actual theft of a SIM card or corrupt mobile phone company employees transferring control of a phone number to criminals. More here: FCC Proposal Targets SIM Swapping, Port-Out Fraud – Krebs on Security

Yes. However, losing control over a mobile phone number can lead to criminals easily taking over a victim’s online and financial institution accounts. This is why, as you know, passkeys will be a massive improvement over SMS-based 2FA and account resets. I can’t wait for passkeys to become widely adopted!

I used 2 factor verification, and while it’s supposed to be the best security, it sure as heck didn’t secure my account.

Lynda, I certainly echo the sympathy for your plight others here have expressed. However, Adam is asking the same question that occurred to me as well: Could the supposed thief in the hotel have unlocked your iPad with its passcode? This the code you would enter when Touch ID failed for some reason. Also, your iPad would likely have prompted you from time-to-time (and certainly after a restart) to “enter your passcode to enable Touch ID.” The question would be was that a simple four-digit code that might have been guessed by looking at the smudge patterns on your iPad screen, or by someone who knew, for example, the last four digits of your cell phone number, or your street address number?

And please don’t misunderstand, I’m in no way trying to “blame the victim” here. Just trying to help get to the bottom of the mystery.

Anything is a possibility, but I don’t remember using a password on this in months.

But you can turn it off, no? According to what I’ve seen, this will remove your Apple Pay cards, and give you a warning about all your other data being available to anyone who uses the device. The text of the warning message seemed to imply that turning off the passcode disabled all security, but I couldn’t find anything specifically stating that was the case.

I believe that biometrics like Touch ID and Face ID require a passcode. Remove the passcode and there is no need for Touch ID - the device is never locked.

How do you get into the iPad after it updates to a new version of iOS? The passcode is always required at that point.

I just saw this post on Mastodon today: Baldur Bjarnason: "Turns out that Adobe is collecting all of its cus…" - Toot CaféJust FYI.Adobe clarifies that this is not used to generate images from customer images. So, never mind.

Is this only in the new subscription based products? I am using LR6 and do not share with the cloud but I have friends using the current version.

Diane

Interesting. I have no recollection of adjusting this, but I just checked and the machine learning is already turned off on my account. Of course it’s possible I just glanced at it a long while back, thought “that seems intrusive and doesn’t need to be turned on” and flicked it off and never thought about it again. I tend to default to turning off/opting out of these sorts of privacy invasions when I can.

Worth checking on your accounts if anyone has them with Adobe.

Trying to follow this Screen Time lock issue. Two questions about your statement above:

Final question do you disagree with Adam’s final sentence in his post that you were replaying to, “All that said, if you both turn on the Screen Time passcode and set a recovery key, you’re safe. There’s no way to turn off the Screen Time passcode without having access to the recovery key.” ?

Yes, it was with 16.4.1. The first time I tried I must have hit something wrong. This hasn’t changed. If you know the Apple ID and the passcode for the device, you can still change the Apple ID password and then remove recovery keys, trusted devices, trusted contacts, and then set a new recovery key to frustrate the real owner’s attempts to recover their Apple ID.

I did. In fact, I didn’t realize you could skip that step - it’s not obvious that hitting cancel still allows you to set a screen time password. But it doesn’t matter - I just tied, and if you hit forgot screen time passcode, it still goes through the same prompt for your Apple ID, and you can still reset the Apple ID passphrase.

Yes.

Thanks! Just to be completely clear about the sentence above:

The starting point of the whole topic is how much damage the thief can do by having the phone and having the passcode. The sentence above says if he also has the Apple ID, by which I assume you mean Apple ID name and Apple ID password, which is a different scenario from just having the passcode.

Thanks

I can answer my own question by experiment. You are correct… Screen Time password is not the answer even with Recovery key set (which I have), though it does put some more obstacles in the thief’s path. Maybe some less knowledgeable thieves would be stopped. Also some of the branches possible might lead the thief to a delay in Recovery, but the sequence below is instant break in.

I just went through these steps:

Screen Time settings > Change Screen Time passcode.

Click Forgot Passcode

Enter Apple ID email but not password…click forgot Apple ID password

Get screen asking for iPhone Passcode which thief has. Enter Passcode leads to screen to enter new Apple ID password.

While doing the above I had “enable reset of Screen Time with Apple ID” enabled, but accept that when you tried with it disabled you reached the same end point. EDIT confirmed by repeating with reset with Apple ID off.

Yes! But even with a screen time passcode blocking access to account changes, there are a number of ways that a thief can find the phone’s logged in Apple ID:

If you have a family plan, you can find it in that section of the settings app.

Also on the settings app, in the AppStore section, it’s probably listed as the sandbox account for almost everyone.

Again in settings, you may find it at the bottom of the TV settings.

Open the iTunes Store app and you will probably find it at the bottom.

It’s probably one of the email addresses on the phone in the mail app. You can also search the mail app for any messages from Apple.

Yes, as I found in my later post, you only need the Apple ID email which is easy to find, not the Apple ID password.

Even though it easy to circumvent the screen time password I am leaving it set on my iPhone, at least for now. It does put some obstacles in the thief’s path.

I want to see how inconvenient having it on is in my normal daily use.

I’m confused about your Screen Time instructions:

Under “Content & Privacy Restrictions” for Screen Time, am I making 1 or 2 changes.

AND

"If you enable Screen Time, set a separate four-digit Screen Time passcode, navigate into Content & Privacy Restrictions, and select Account Changes > Don’t Allow…

Unfortunately, the Screen Time passcode does that by preventing anyone, including you, from entering Settings > Your Name to make changes without first going to Settings > Screen Time > Content & Privacy Restrictions > Account Changes > Screen Time Passcode > Allow.?

I think the confusion is the italics. In TidBITS style, italic text in a sequence like that indicates something you type or that’s different for every user—in this case, your Screen Time passcode. I’ve bolded those above for clarity.

There’s no need to block passcode changes; the thief has the passcode already and doesn’t need to change it.

I have just tested this again (first time since May) and in iOS 17, with the 28 digit Recovery key set, I am finding it impossible to change Apple ID account password if a Screen Time Passcode is set.

This was not true in May (even though I had Recovery key set at that time). In May, attempting to turn off or change Screen Time passcode, and clicking forgot passcode or forgot password, eventually led to requiring the phone passcode which the thief already has.

Now the same sequence leads to this screen:

The thief would not have the 28 digit Recovery Key.

I don’t know if this is an iOS17 change or Apple has changed something behind the scenes.

I read the article. Basically a shoulder surfing thief can watch you type in a passcode, grab your phone, and use the passcode to get access to your entire phone including all of your accounts. Except…

The solution is to always use TouchID or FaceID when you’re out and about. They both work so seamlessly, you can almost forget your phone is locked. So, set them up.

Since you’ll FaceID and TouchID use 95% of the time, using more complex passcodes is much easier. Apple defaults to six digits which is barely acceptable. It’ll be hard for a shoulder surfer to get all six digits. However, older users have four digit passcodes which is unacceptable.

The iPhone has four options:

The idea is to prevent the shoulder surfer from picking up the entire passcode. If the thief gets only four digits of a six digit passcode, they’ll have to guess the last two, they really can’t do any damage. After five attempts, the iPhone will take longer and longer to allow the next guess.

The idea is speed and length. Thus, option #3, an extra long digital passcode is the best option. You can type it pretty fast, and a shoulder surfer might not be able to pick up the code. Note that if you choose option #3 and your passcode is just six digits long, Apple will treat it as a six digit passcode. That means it’ll prompt you that the passcode is six digits. That will make it easy for. Shoulder surfer to pick up.

Option #4, Alpha numeric passcodes might be too slow for you to type, and if your passcode is a word, the shoulder surfer could pick that up.

I’ve noticed that Android still defaults to four digit passcodes. Even worse are the swipe pattern locks. I’m glad Apple never implemented them. I’ve been able to shoulder read swipe patterns without even trying. Heck, most people use the same swipe pattern — around the perimeter then diagonally from bottom right to top left. It’s like leaving your car keys in the toe of your shoe when you go swimming at the beach.

So setup TouchID and FaceID and use them. If you suddenly find yourself out and about and must use your passcode, check around you for shoulder surfers. Use either the extra long numeric passcode or an alphanumeric passcode that is not a simple word. Make sure you can type it fast without hunting and pecking.

If you speak a foreign language that uses a Non l-Latin alphabet, you can use your non-Latin keyboard for the passcode. Unless the thief is familiar with the language, they’ll probably never figure out your passcode.

At the risk of reiterating the issues this brought up, what you missed is that somebody with your phone can reset the Apple ID passphrase and set a recovery key that you won’t have with only the iPhone’s passphrase. This will effectively lock you out of your Apple ID permanently, and, so far, very few people have convinced Apple to give them access back. You’ll lose any apps you’ve purchased, subscriptions you’ve been paying for (and I’d say it’ll be hard to stop recurring charges until you cancel the credit card), iCloud backups of your device; if you use Messages in iCloud, all of your message history. If you have an Apple Watch, all of your Health information. Obviously, the more you use iCloud, the more you stand to lose.

I’ve verified what @mikebhm reported - that iOS 17 has made it even more difficult to reset the Apple ID passphrase if you’ve set a recovery key. In fact, it adds a step that requires another device linked to your iCloud account (if you have one) to approve the change to the Apple ID passphrase when you set a screen time restriction on account changes - a big improvement from iOS 16.

Thanks Doug, I don’t remember the ability to reset the Account Recovery Key coming up before but you are correct. So presumably the thief now has to do this extra step before he can turn off Screen Time lock and thus changed Apple ID password.

Is that why you say iOS17 has made it more difficult than iOS16?

WAIT! What I wrote above is wrong,

The thief does not have access to either the Recovery Key reset or “FaceTime and passcode” setting while Screen Time Code is set. And he can’t turn off Screen Time Code without the Recovery Key.

So I am back to believing what I wrote in my previous post that iOS 17 has fixed this issue…

And it appears this indeed the crucial issue for those of us who use iCloud Keychain.

I’m no fan of 1Password and all those apps, especially not those that somehow require a subscription. But I’m afraid this loophole (which apparently is by design, not just a bug) is a strong argument against relying on iCloud Keychain and in favor of instead getting a 3rd party password manager that is secured with a different and unique master password.

I don’t want to switch away from iCloud Keychain. I really wish Apple would change this design. Or at least give us an option to trade off last resort recovery vs. securing this potential weakness.

What I wrote was shorthand. Previously, up to at least iOS 16.4 (I never tested much after that version), anybody with your phone’s passphrase could reset the Apple ID password, even with a screen time passphrase and account change restriction set, so long as they also knew the actual Apple ID address (which is discoverable from other areas in the Settings app, from just looking at your email accounts, etc.)

Once the thief changed the Apple ID password, they could then remove a recovery key that you set from the Apple ID settings webpage, and create a new recovery key that only they knew, to prevent you from regaining access to your Apple ID (they could also remove any trusted devices from your Apple ID settings, so you wouldn’t be able to quickly go back to a Mac or iPad that uses the same Apple ID to regain access.)

As you detailed in your post above, if you have set a recovery key yourself, a thief would need to enter the recovery key before they would be allowed to reset the Apple ID password. At least so far this suggests that this loophole is now closed.

Thanks for confirming Doug.

The second Wall Street Journal article covered this. However, this is still contingent upon someone getting access to your iPhone, knowing your passcode, and unlocking it. Using TouchID and FaceID on a regular basis will make it easier to keep your passcode safe.

The problem seems to be in bars. A group of several thieves work in concert, targeting people who are using passcodes to open their phones. One thief start getting friendly with the person. Meanwhile, another one gets in position to read the passcode while another one gets in position to grab the phone at the right opportunity. It looks like the phone is grabbed when placed onto the bar.

One software change could be to require the Apple ID password to change the passcode, to open the iCloud settings, or when the m user doesn’t want to use FaceID or TouchID to do certain functions such as ApplePay. Maybe Mail and Messaging should require TouchID or FaceID too.

Then again, the sheer number of people who can’t remember their iCloud password is astounding. And you could be just getting someone to shoulder surf your Apple password too. Or that constantly using FaceID and TouchID makes the phone clumsy to use.

Yes I guess that would have been an alternative. The solution that Apple have introduced in iOS 17 is less intrusive on everyday tasks.

Perhaps you may find this interesting?

Using a third-party password manager alongside keychains

Doug, I have been shot down in another forum. In iOS 17 it still possible to change Apple ID password with just the phone passcode. Details in this post.

Thanks for the follow-up. Boy, I really hope that Apple adds an option to shut this down for people who don’t want this ability.

This is a News+ link from the WSJ, but Joanna Stern is reporting that the iOS 17.3 beta is including some new protections against this attack.

Let’s see if this link works for those who don’t have News+

So is the idea that in that 1-hr delay window you have time to register the device as stolen? But does that help if the thief also has the passcode? Can Find My’s Mark as Lost not be overridden on device with the device passcode? Or would that indeed require the iCloud password thus allowing you to block your iPhone even in the event the thief also has the passcode?

In the past, using biometric ID has always been optional; when it didn’t work, you fell back to using a password or passcode. However, with Stolen Device Protection on, biometric ID will be required for many operations if you are not in a ‘safe place.’ For critical operations, you must biometricly authenticate twice, with the authentications separated by at least 1 hour.

However, if you are in a ‘safe place,’ everything works as before. The safe place option is there because biometrics have been known to fail.

I think having safe locations as the only way to get around Stolen Device Protection’s restrictions might be too restrictive and not restrictive enough. A place where your identity might be compromised might be within the perimeter of a safe location (a bar downstairs from your apartment?). If you are traveling and not stopping in any location for more than a day or two (e.g., a performer on tour), you might have vital functions disabled for an extended period.

Perhaps an alternate method would be a protocol involving an account recovery contact.

I agree with that. For some this could be too restrictive, for others (or for other situations) not enough.

I like to see an option where you’re required to authenticate on another AppleID-connected device. What are the chances the thief copies down my passcode, steals my iPhone and then also snatches my Mac? Not to mention he’d need the Mac’s password too (which obviously isn’t the same as the iPhone’s).