How a Thief with Your iPhone Passcode Can Ruin Your Digital Life

Joanna Stern and Nicole Nguyen of the Wall Street Journal have published an article (paywalled) and accompanying video that describes a troubling spate of attacks reported by individuals and police departments aimed at iPhone users that may involve hundreds to thousands of victims per year in the United States.

Watch the video, but in short, a ne’er-do-well gets someone in a bar to enter their iPhone passcode while they surreptitiously observe (or a partner does it for them). Then the thief steals the iPhone and dashes off. Within minutes, the thief has used the passcode to gain access to the iPhone and change the Apple ID password, which enables them to disable Find My, make purchases using Apple Pay, gain access to passwords stored in iCloud Keychain, and scan through Photos for pictures of documents that contain a Social Security number or other details that could be used for identity theft. After that, they may transfer money from bank accounts, apply for an Apple Card, and more, all while the user is completely locked out of their account.

And yes, they’ll wipe and resell the iPhone too. Almost no crimes like this have been reported by Android users, with a police officer speculating that it was because the resale value of Android phones is lower. In the video, Joanna Stern said a thief with the passcode to an Android phone could perform similar feats of identity and financial theft.

The Wall Street Journal article details three kinds of attacks, only one of which is clearly avoidable. The one that’s heavily emphasized in the article I describe above. But Stern and Nguyen also spoke to victims who were drugged—a sadly common problem—and interviewed others who were subjected to violence to reveal their code. In no case have the victims done anything wrong, and anyone who frequents bars or similar venues in urban areas should beware.

Given the high profile of the Wall Street Journal coverage, I fully expect Apple to address this vulnerability in iOS 17, if not before. The obvious solution is to require the user to enter the current Apple ID password before allowing it to be changed in Settings > Your Name > Password & Security > Change Password. That won’t block access to iCloud Keychain, but at least it would let the user wipe the iPhone.

Apple probably hasn’t prompted for the current Apple ID password in the past because the passcode is considered a secure second factor—you have the iPhone, and you know the passcode. In contrast, when you log in to the Apple ID site to manage your account, you must provide your current password, go through two-factor authentication, and enter the current password again to change it. It seems like an easy change to make, at least until Apple has had a chance to think through other options.

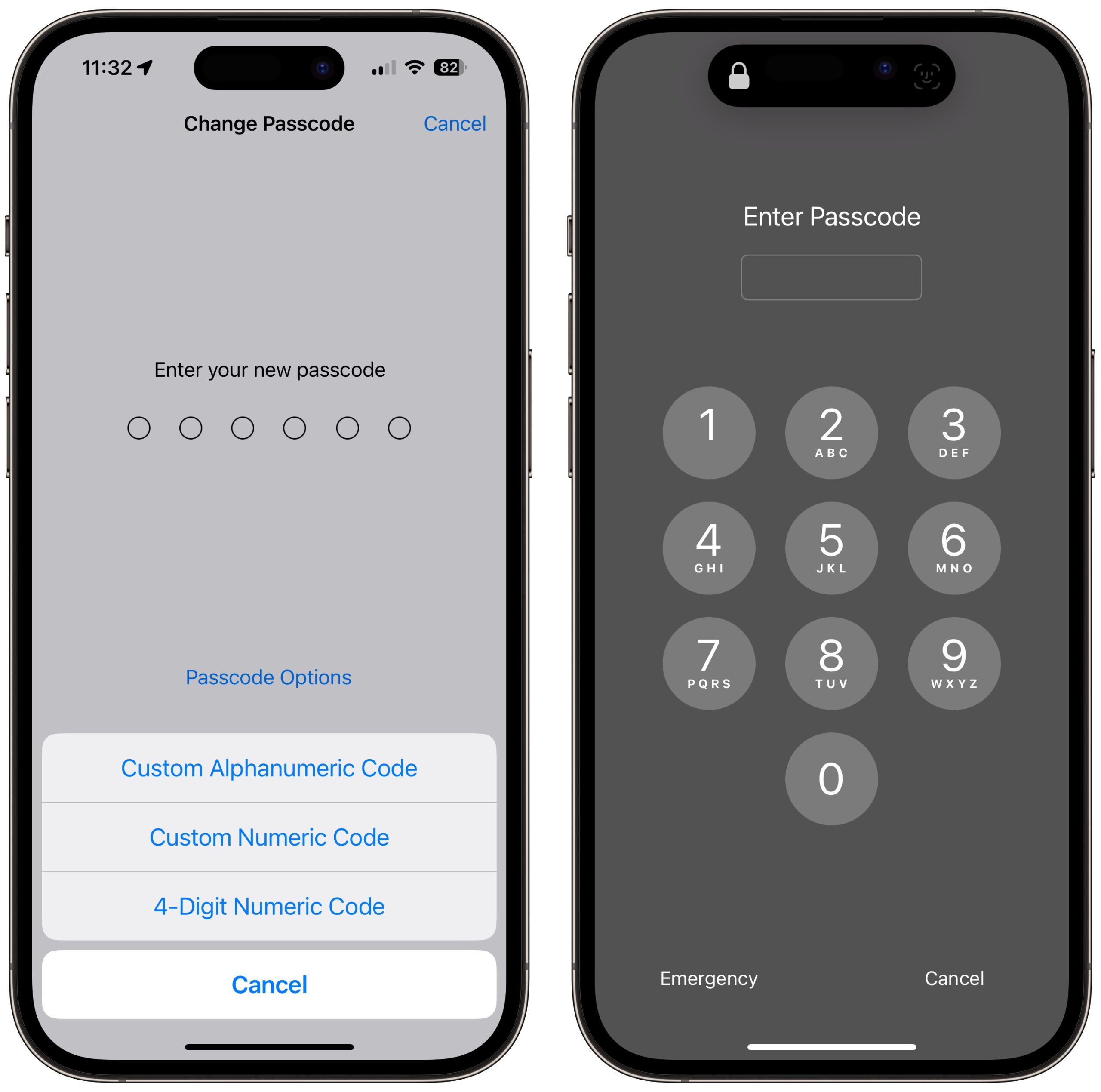

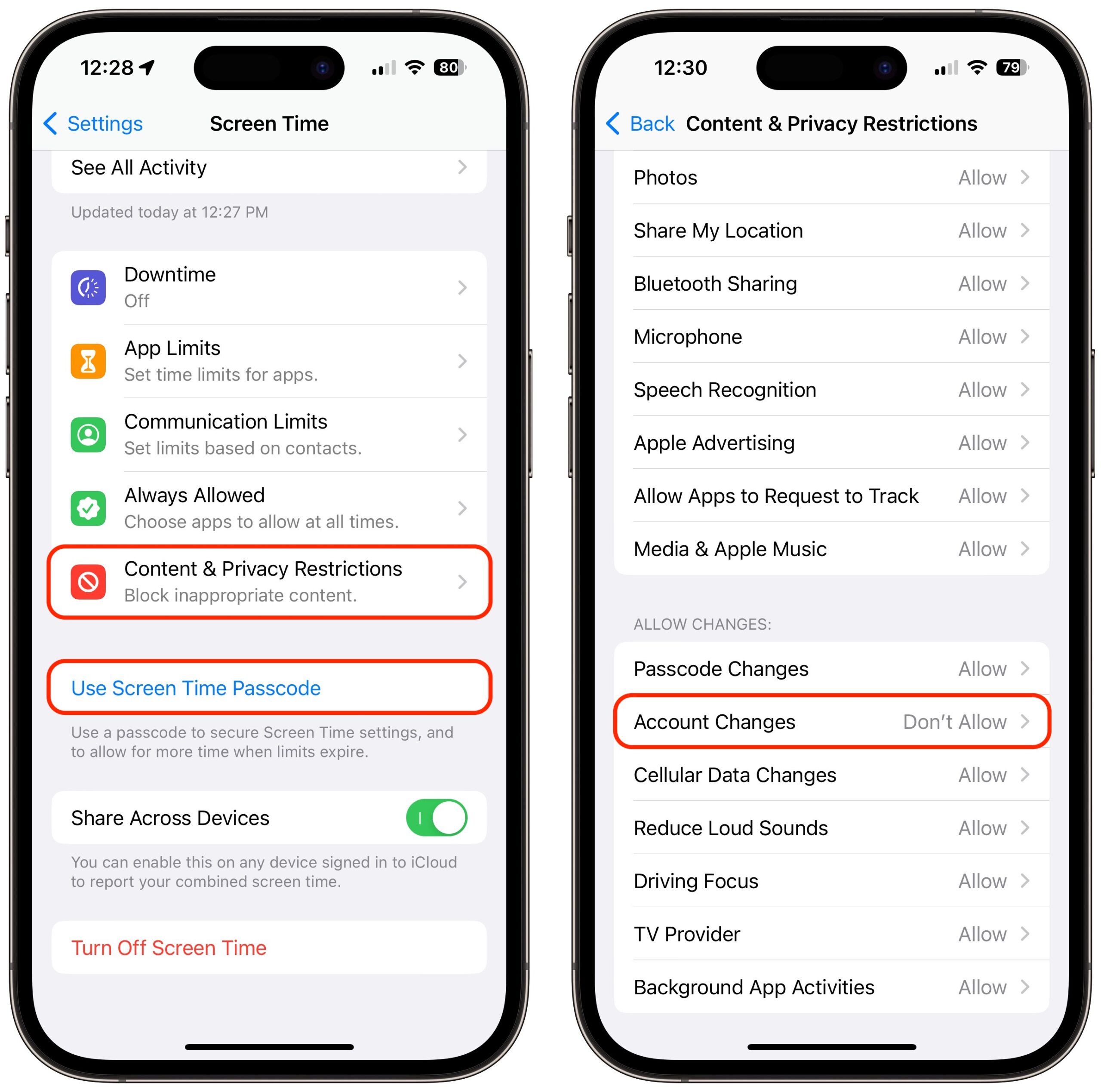

The closest we have to an additional password step is a Screen Time passcode. If you enable Screen Time, set a separate four-digit Screen Time passcode, turn on Content & Privacy Restrictions, and select Account Changes > Don’t Allow, no one can change your Apple ID password without that passcode. Unfortunately, it prevents you from even entering Settings > Your Name without first going to Settings > Screen Time > Content & Privacy Restrictions > Account Changes > #### > Allow. Most people wouldn’t put up with such a speed bump.

Another flaw that Stern and Nguyen note is that Apple’s new hardware security key option, if enabled, doesn’t always prompt for the hardware key when making changes if the user has the device passcode (see “Apple Releases iOS 16.3, iPadOS 16.3, and macOS 13.2 Ventura with Hardware Security Key Support,” 23 January 2023). The security key protection can be entirely removed, too, without having one of the hardware keys. Apple should re-evaluate how this high-security option—albeit one only a subset of users will employ—lives up to its promises.

How to Protect Yourself

You might think you would never be the victim of a watch-snatch-and-grab theft, being drugged at a bar or on a date, or a violent crime. But the theft of a passcode can happen in other circumstances. And it has such severe consequences, as the Wall Street Journal reporters noted, that even if you’re not a barfly or live in an area with a high incidence of violent property theft, I think everyone should take stock of these ways to deter malicious use of their passcode:

- Pay attention to your iPhone’s physical security in public. These attacks require both your passcode and physical possession of your iPhone. Many of us have become blasé about exposing our iPhones in public because we use them constantly and because everyone else has smartphones as well. Apple has also done a great job with the message that an iPhone is useless to a thief due to a passcode protecting its contents and Activation Lock ensuring it can’t be resold intact—this probably makes us less concerned about its security even if there’s a hassle and expense in replacing it. There’s no good way to prevent a thief from grabbing the iPhone from your hand when you’re using it, but if you can keep it in a pocket or purse when it’s not in use, rather than holding it or leaving it on the table in front of you, that reduces the chance that a thief will target you.

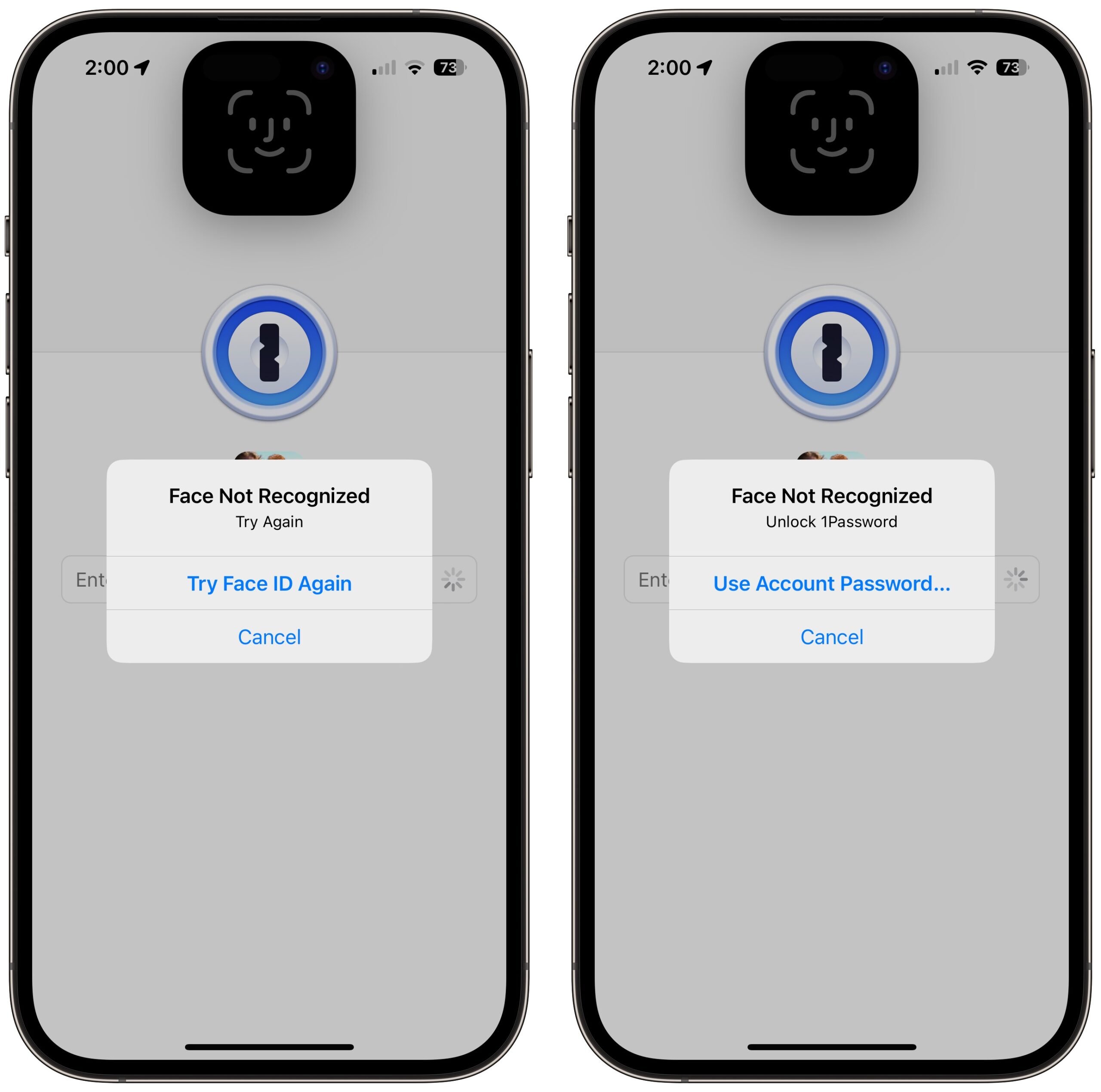

- Always use Face ID or Touch ID in public. The key to these attacks is acquiring the user’s passcode; the easy way to do that is to observe or record you entering it. If you rely entirely on Face ID or Touch ID, particularly when in public, no one can steal your passcode without you knowing. (Police believe those who are drugged while drinking have their faces or fingers used, but that doesn’t reveal their passcodes.) If you have been avoiding Face ID or Touch ID based on some misguided belief about the security of your biometric information, I implore you to use it. Your fingerprint or facial information is stored solely on the device in the Secure Enclave, which is much more secure than passcode entry in nearly all circumstances. If you are one of the few people for whom Face ID or Touch ID works poorly, conceal your passcode from anyone who might be watching, just as you would when entering your PIN at an ATM.

- Consider a stronger passcode. By default, iPhone passcodes are six digits. You can downgrade to four digits, which is a bad idea, but you can also upgrade to a longer alphanumeric passcode. In the video, Joanna Stern recommends that, and it might make it harder for someone to observe surreptitiously, but I’m unconvinced the increased security would be worth the added effort. Someone could still record you entering your alphanumeric passcode, and the longer and harder it is to enter, the more time it will take and the more focused you will be on typing it correctly, making you less aware of your surroundings. (Interestingly, if you set an alphanumeric passcode with just digits, you still get a numeric keypad to enter it, whereas if you add non-numeric characters, you have to use the full keyboard.) Still, I can’t recommend most people go beyond a standard six-digit passcode. Just make sure it’s not something trivially easy to observe or guess, like 111111 or 123456.

- Never share your passcode beyond trusted family members. If you wouldn’t give someone complete access to your bank account, don’t give them your passcode. If extreme circumstances require you to trust a person outside that circle temporarily, change the passcode to something simple they’ll remember—even 123456—and change it back as soon as they return your iPhone.

- Use a third-party password manager instead of iCloud Keychain. It pains me to recommend this option because Apple keeps improving the interface to iCloud Keychain with Settings > Passwords and System Settings/Preferences > Passwords. But until the operating systems protect access to iCloud Keychain passwords with more than the passcode, relying on iCloud Keychain is just not safe enough. In contrast, third-party password managers secure your passwords with a separate password. Even if they support and you enable biometric unlocking, the fallback is the password manager’s account password, not the device passcode.

- Delete photos containing SSNs or other identification numbers. It’s common to take a photo of your Social Security card, driver’s license, or passport as a backup, just in case you lose the real thing. That’s not a bad idea, but storing such images in Photos leaves them vulnerable to these attacks. Instead, store them in your password manager. Search in Photos on

SSN,TIN,EIN,driver’s license, andpassport, along with your actual Social Security and other identification numbers. Also search onVisa,MasterCard,Discover,American Express, and the names of any other credit cards you might have photographed as a backup. (Searching for text in Photos works in macOS 13 Ventura and iOS 16. For older operating system versions, try Photos Search; see “Work with Text in Images with TextSniper and Photos Search,” 23 August 2021.)

My Response

I’m putting my time where my mouth is. Even though I’m at a very low risk for these attacks, which primarily target bar-goers in large cities and people in areas with frequent street crime, I’ve taken steps to reduce my exposure.

First, I already rely on Face ID whenever possible, and I’ll be even more aware of who’s watching while entering my passcode if Face ID fails and I’m forced to tap in my secret digits. I’m already slightly embarrassed to have my iPhone out when I’m in public when I’m not using it, and I’ll probably keep it in my pocket even more than I used to.

Second, I decided to clear out all my iCloud Keychain-stored passwords. On my MacBook Air, I went to System Settings > Passwords, selected all of them, and pressed Delete. (You can also do this in Safari’s Passwords settings pane.) Because I have never seriously used iCloud Keychain, this was no hardship—everything in there was essentially random. Until recently, I used LastPass, but after LastPass’s breach, I switched to 1Password and imported all my LastPass passwords (see “LastPass Shares Details of Security Breach,” 24 December 2022). I had a lot of passwords already stored in 1Password from various imports and tests over the years, plus the vaults I share with Tonya and Tristan. Whenever I use a password now, I take a few minutes to clean up duplicates and related cruft, like leftover autogenerated passwords.

I realize those who rely on iCloud Keychain won’t be comfortable deleting their passwords, but I can say that I found it simple to switch to 1Password from LastPass, and 1Password offers instructions for exporting iCloud Keychain passwords and importing into 1Password. Do the export/import dance and live with 1Password—or whatever password manager you choose—for a week or two to make sure it’s working for you before deleting everything from iCloud Keychain. If you decide to return to iCloud Keychain in the future, that’s possible too.

Third, I visually browsed and used text searches in my Photos library for identification cards and the like, exporting a few for import into 1Password and deleting everything afterward. (Remember that Photos stores deleted images in the Recently Deleted album for about 30 days before deleting them permanently. To remove them immediately, select the photos in that album and hit Delete.) I found my driver’s license, passport, credit cards, insurance cards, and other cards from my wallet. Make sure to click See All after performing a Photos search if there are more than a handful of results. I even searched on card and scrolled through 500-odd photos to find a few that escaped other searches. (Who knew I took so many photos containing cardboard?)

I briefly considered moving those sensitive images to the Hidden album in Photos and using the new iOS 16/Ventura option to protect that album with Face ID or Touch ID. Unfortunately, when I tested multiple Face ID failures on my iPhone, I was eventually prompted for my passcode, which revealed the Hidden album. It’s another example of how the passcode is the key to your kingdom.

While the chance of any given person falling prey to this sort of attack is vanishingly small, and I’m not actually worried for myself, the Wall Street Journal reporting led me to think about and clean up my broader security assumptions and behavior. I appreciated the nudge, and I’d encourage you to reflect on your security situation as well.

This is indeed a bit scary, especially for those of us who also use ApplePay/AppleCash or iCloud Keychain.

I use encrypted notes for some sensitive information. Usually this unlocks with FaceID, but testing that with my wife’s face I see that it also accepts passcode as backup for FaceID. Is there any way to force a different password for those encrypted notes?

I have a longer alphanumeric passcode which certainly makes it safer, but I’m under no illusion that this is entirely sufficient. Indeed, Apple should at the very least require you enter your old iCloud passcode before you can set a new one.

Even then, at the end of the day the underlying vulnerability is that we have all our eggs in a single iPhone/iCloud basket. Sure, I could use 3rd party password managers and such, but that breaks a lot of the elegance of Apple’s highly integrated approach we so much enjoy. Anyway, the easiest and cheapest method will always continue to work:

Source: xkcd

I am continually surprised by how many people store ordinary photos of sensitive documents on their phones without any special protections. I’ve stored that kind of information in 1Password (on my Mac) since long before I got my first iPhone.

Then again, I routinely find myself facepalming at how many people share front-and-back pictures of their credit or gift cards on social media, and later complain about being hacked. Basic personal security, like basic personal finance, really needs to be part of the standard school curriculum.

No, but Settings / Notes / Password and you can set a custom password (which will disable Face ID/Touch ID). I believe you have to unlock and relook notes that already exist with the (new - this started in iOS 16 I believe) biometric unlock method.

As for changing the Apple ID passphrase from the device with the device passcode, it should be mentioned (I don’t believe that Adam’s article does) that the WSJ suggested using a screen time passcode (different PIN from your phone’s PIN, obviously) and in Settings / Screen Time / Content and Privacy Restrictions change “Account Changes” to “Don’t Allow”. This will lock the change password function until you toggle this back on (and you can’t toggle back on without the screen time passcode). (If you make this change you’ll notice that you can no longer access the Apple ID settings at the top of the Settings app.)

Good article.

This trick:

Just today, I was blown away at how good this text recognition is. I was looking for pictures of my power meter (do you just photograph things these days to take a note, too?) by just typing the words “Meter”. Photos successfully pulled up a picture, taken 7 years ago with a handwritten note visible and turned sideways, that had the word “meter” scribbled. Very clever.

Rob

Adam, many thanks for passing this on! I’m about to head off for a business trip in an unfamiliar place, and while I usually use FaceTime to unlock my phone, it’s good to know about this significant security flaw with the passcode. I’ll be very careful if I have to enter it in public.

After reading the WSJ report and the associated article on how to protect your phone, I did what @ddmiller suggests and set up a Screen Time passcode, then disabled Account Changes on my phone. That seems like an easy way to prevent changing the Apple ID password, absent the kind of extortion that the xkcd posted by @Simon shows.

Very interesting, thank you.

I do not use Keychain as a password manager (I use Dashlane) but I see that iCloud Keychain is switched on on my iPhone and Mac. There are over 100 passwords in the Mac’s Keychain Access app many for com.apple.xxxx objects and very few for stuff I recognize. Questions:

I may come in for criticism here but I think all of these security alarums are over the top for the average person.

The average person is much more likely to leave their ($1,000 Supercomputer!) phone on the table in the cafe than they are going to be drugged or mugged in a bar. They do it all the time. That is the prime security vulnerability. Just the other day at Starbucks I saw someone waltz off to the bathroom leaving their laptop and phone on the table. What!?

More so when you’re traveling. Thieves have learned that jet-lagged travelers are kind-of unconscious and are easy marks for a quick motor bike swoop and phone grab.

It’s clear that Apple must eliminate the iPhone passcode validation for an AppleId change and maybe should implement a separate level password for icloud keychain. Those are really bad and it’s surprising they chose to offer them. I’m guessing they’ll change them very quickly.

In the meantime, unless you live in bars and are frequently inebriated I’d wait to make huge, tiresome changes to your password system for a month or so to see what they do.

Oh! And get those ID pictures out of your Photos! Jeez!

Dave

Just searched for my surname in Photos, 196 images.

Some IDs but a lot of snaps taken for functionality as well which could be used, bills, etc.

Another argument for the watch for tap-to-pay. I only ever unlock that in the morning when I put it on.

You are right that this probably isn’t that big a risk for many people, but the WSJ article explained it’s not just being drugged or mugged.

It sounds like it’s a lot of young, single people socializing who are vulnerable to this sort of attack. But I could see people tourists in foreign countries falling victim to something like that by charming locals in bars, too.

I know that this is a less of an attack that will risk losing your Apple ID, but another attack I’ve read about recently (this pops up on Reddit a lot) are people whose phones are stolen by people on bicycles as they stand on or near a street after unlocking their phones (on the curb, crossing a street, etc.) The thieves are watching for people taking out their phones and unlocking them (maybe to check on the location of their Uber driver, or getting directions, or just unlocking a device). These thieves don’t have the passcode, so some of the risks - draining bank accounts, etc. - may be less likely, but with the phone unlocked they can still scan photos for any personal info, perhaps send themselves money with Venmo, quickly turn off cellular and WiFi (to make tracking by find my impossible), and then just sell the phone for parts, or even sell them to rubes who don’t understand that they are Apple ID locked or IMEI blocked.

The WSJ article strikes me as one where the reporter found an interesting anecdote or set of anecdotes and spun that into a giant trend piece. There’s no actual evidence in the article that this is happening more frequently than it always has, just individual stories and police saying scary things. The focus on Apple fits with that, as it hooks it into the “Look What Apple’s Doing!” genre.

The two specific vectors mentioned are actually substantially different. If you get mugged/drugged/kidnapped, no level of reasonable security is going to help. The criminals will just keep asking for what they need, using (as Simon/XKCD pointed out) a $5 wrench to get it. The 1980s version of this was the ATM breach, where muggers would force people to withdraw money from their accounts at gunpoint. Not much use in having a complicated security setup if you have a muzzle in your face.

If they read your passcode and get your phone, then additional security can help, but it’s a balance. I guarantee that a lot of people are going to end up locked out of iCloud if they need to use a separate password for it. The ATM example is instructive here as well – if people needed to enter multiple different PIN numbers to get to various accounts, it would have caused a fair amount of chaos.

Generally, I’d like to see some evidence that this is actually happening frequently before panic sets in.

As a result of reading the WSJ article, I changed my four-digit iPhone lock code to an alphanumeric password. I rarely take action based on articles in the popular press, for most of the same reasons as some of the more cynical posts in this thread have pointed out (news media exists to sell advertising; disseminating information is at best a secondary goal). However in this case, the scenario of someone shoulder-surfing my fairly simple code and then stealing my phone seemed plausible enough, and the risks high enough, to warrant action. I decided to use the same password as my iCloud account, since this is essentially the same resource, and it is one of the only complex passwords I’ve committed to memory.

And you know what? The few times since making the change where I’ve had to enter that password, it actually feels right. I know that’s not a measurable benefit, but I’m already starting to look back at my four-digit days with a “what was I thinking?” mindset.

Does it require switching to a different screen for the alphabetic characters or is an alphabetic keyboard displayed in addition to the numeric one?

The standard alphanumeric keyboard is automatically displayed if you have a “complex” passcode. Bonus: I discovered testing this before I replied that if the “Enter passcode” prompt is on the screen, and you subsequently put your face in front of the camera, your (obscured) passcode is filled in automatically and the phone unlocks.

A number of digits more than 4 for me and my bride…that way it’s not obvious how many digits are involved…but it’s almost always unlocked via TouchID anyway for us…and we have the erase after 10 tries option enabled as well…although supposedly some of the hardware cracking devices from Israel can get around that IIRC.

Another item that the WSJ covers is how the thieves used access to the phone to create an iCloud Account Recovery Key, if one had not been made, which locked people out of their accounts entirely because they could no longer reset their password on their own.

While it would make sense to generate a recovery key ahead of time to prevent that, I haven’t found any good guidance on how to store it - obviously, if you keep it in Notes, it’s going to be accessible on your device and therefore too accessible if your device is stolen. But I also don’t think I want to print it out and keep it in my desk drawer if I needed to get at it while on a trip.

I keep ours in a secure note in Enpass, synced across all my devices.

I don’t have a very new iPhone, but I lock mine with a SIM PIN, too.

I have mine in 1Password plus recorded in an encrypted disk image on one of my Macs. If you use an encrypted Note using a passphrase (rather than using your device passcode and biometrics to unlock), that would not be readable.

Also, going back to the WSJ recommendations: if you use iCloud Keychain and fall victim to this PIN surfing attack, locking out the ability to change the Apple ID password with a screen time passphrase isn’t much of a protection if the Apple ID passphrase is stored in the iCloud Keychain. They can just log in to the Apple ID with another device, use your phone as a trusted device to approve the new log in, and then change the password there.

The article does point out that using a third party password manager that has a separate passphrase is much more secure.

Perhaps Apple should think about some way to protect iCloud Keychain (with a separate PIN perhaps) that allows unlock with biometrics and times out after a period of time. Perhaps one of the screen time restrictions, so it’s optional and not a default behavior?

Is there a way to lock your phone with you Apple Watch, so if people get your phone, you can lock them out?

You can via “Find Devices” on watch, but the idiotic thing is Lost Mode can be turned off with just the device’s passcode, so if the thieves have that (like in the original WSJ article), this won’t be of much use.

Well that was illuminating. I had no idea of how many of the old undeleted temporary note photos I have on my phone have sensitive data. I found one page of a tax return from a couple of years ago, several hand written passwords, too many sales receipts, accidental screenshots, photos of monitors with more than the window I was aiming at…

But I also discovered that using search won’t find everything. It seems to be better at words than pictures, but I’m still finding plenty that need to be deleted as I look through everything by hand. The worst so far is a screenshot from when I was looking at my Apple Card number. (I have double back tap set to do screenshots, and also the habit of drumming on the phone while doing things. Oops.)

Yeah, I added this yesterday after the initial posting of the article. I played with it a bit and it was so utterly annoying that I can’t see many people seeing it as worth the tradeoff in standard use (but possibly worthwhile for a limited period, such as a trip). I had hoped that it would prompt for the Screen Time passcode when you went to change the Apple ID password, for instance, which would be fine, but instead it blocks all access to all account settings, and the only way to regain access is to disable the Account Changes setting. (After which you’d have to re-enable it again.)

Sure, and I pointed out that physical security is important, but lax physical security just reinforces the need for protecting the passcode even more.

I don’t think there’s any claim in the article that these crimes are happening more frequently in the past, just that the reporters have just now assembled all the stories and technical underpinnings. My conclusion was that law enforcement has only recently started to put all these crimes into the same statistical bucket. It’s possible that the article will cause more police departments to realize what’s happening. As far as numbers, they’re not hard statistics, but the relevant quotes would seem to be these, and while they come from police, I’m not sure where else they could come from.

I don’t think this will make any difference to the passcode attacks because it only affects cellular usage and only after a restart or SIM swap. Apple says:

If you rely on Dashlane, I can’t see that you’d lose any functionality if you turn iCloud Keychain off. And, as long as the passwords you have in iCloud Keychain are also in Dashlane (which was my situation), there’s no harm in deleting them.

Ben Evans on Twitter reminds us of the already existing content and privacy restrictions in "Screen Time " settings that provide a layer of protection to your Apple ID and Passcode.

https://twitter.com/benedictevans/status/1629541926956351488?s=20

The basic steps are:

Enable a passcode for Screen Time

Settings\Screen Time\Screen Time Passcode

Note - just don’t use the passcode of your device. Also store a copy of the new pin somewhere safe

Restrict Access to Passcode

Settings\Screen Time\Content and Privacy Restrictions\Allow Changes\Passcode Changes\Don’t allow

Restrict Access to Apple ID

Settings\Screen Time\Content and Privacy Restrictions\Allow Changes\Account Changes\Don’t allow

When you implement the changes, the settings for Apple ID and FaceTime (Passcode) will be greyed out.

Workflow.

Whilst “don’t allow” is set you will not be able to access the Apple ID and iCloud settings on you device. The same applies for FaceTime settings.

When you do need access to these areas, just go into Screen Time and adjust the above settings to “allow”.

You will be prompted for your Screen Time PIN when this happens. Also remember to reset this to “Don’t allow” when done.

Future State

It make senses that Apple provides a more elegant approach to managing your system settings on iOS/IPadOS similar to the padlock approach, or better, on the MacBook.

The entire article is framed as if this is a new and increasing threat: cases are “piling up in police stations around the country.” "“This is growing,” he said. “It is such an opportunistic crime. Everyone has financial apps.” There has been a “recent spate of thefts.”

The problem is not using cops for insight, it’s when that is the only insight. The stories & quotes are anecdotal and played for maximum drama, but without any underlying evidence that shows this is a serious and widespread issue.

To give an example of what I mean, both the FBI Crime Data Reporter and the NYPD’s CompStat dashboard show robberies and burglaries down substantially year over year, both nationwide and in NYC.* Does that mean that there couldn’t be a wave of iPhone robberies like in the story? No, but it does make the picture a bit more complex and was something the journalists needed to have included.

*https://cde.ucr.cjis.gov/LATEST/webapp/#/pages/explorer/crime/crime-trend /

NYPD CompStat 2.0

I don’t feel any of this discussion is unwarranted and I don’t sense any “panic” or overt sensationalism. It’s become fashionable these days to discredit sources just because they’re related to LE, but I don’t buy into that. Joanna Stern is, as usual, very serious and points out who is most likely affected by this, ending her segment with concrete steps people can take to protect against such attacks. @ace’s article is very similar and also most appropriately points out what next steps Apple needs to take to limit potential damage from such an attack. I’m very glad the story broke and was treated in the way it has been. I learned something and reconsidered some of my digital habits (even though I’m unlikely part of the “target demographic”). And judging by the replies here, several others have also benefited in similar ways. IMHO this has so far been an excellent exercise in prevention.

As it turns out, there is a way to bypass this - a horrible security bug by Apple in my opinion. Adam, I’ll post the procedure to follow if you want - I’m not sure that it’s a big secret, and I have a strong feeling that people who would be inclined to steal people’s phones already know of this workaround - but if you prefer to keep it off the Discourse, I’ll keep it to myself.

Basically it allows you to change the Apple ID password. You do need to know the Apple ID itself, but that’s generally findable in Settings / App Store, or in the iTunes Store app at the bottom, or just guessing one of the email addresses on the phone itself.

(I have a feeling that this a procedure that kids follow whose parents have put a screen time PIN on their devices to get around restrictions. But, maybe not.)

And I try so hard to avoid being fashionable. In any case, your point is not accurate for my comments since the additional sources I’m suggesting using are both law enforcement.

As to overt sensationalism, the WSJ article absolutely is sensationalizing it. The headlines alone – “A Basic iPhone Feature Helps Criminals Steal Your Entire Digital Life: The passcode that unlocks your phone can give thieves access to your money and data; ‘it’s like a treasure box’” – are impressive clickbait.

If you delete everything from iCloud Keychain, nothing, as long as you keep the passwords stored elsewhere so you can still reference them.

If you delete them from Keychain Access (on your Mac) or Passwords (on your iDevice), you’ll probably have issues. Your known Wi-Fi networks passwords are stored there, as are your Mail.app account passwords. Yes, you can also store them in a password manager, but your Mac can’t automatically access those like it can the ones in Keychain, so you’d have to enter them yourself to connect to networks or check email. Also, most of the com.apple.XXXX entries are AppleID tokens for various apps, and will just reappear after you sign back in to your AppleID, so the only thing you get from deleting them is that you have to sign back in.

If you’ve been using iCloud Keychain, many of the entries will be irrelevant to your Mac, as they’re shared from your iDevice(s), and probably can be safely deleted. But don’t delete them from Keychain Access before turning off iCloud Keychain, or they’ll be deleted everywhere, and some of them may be critical on your device.

Generally speaking, unless you know something you see in Keychain Access is risky or outdated, it’s probably best to leave it alone. If it looks suspicious but you don’t know or aren’t sure what it is, Google it before deleting it. (If it looks suspicious and you do know what it is, that’s different.)

EDIT: Be sure to turn off iCloud Keychain before deleting anything from either Keychain Access or Passwords.

Thanks. Everything I need is in a password manager and in a separate password protected file. However, I’ll just leave Keychain as is for now. I have half a century IT experience and do not find this exactly obvious, no wonder inexperienced users get into trouble.

One additional factor to consider in this particular attack vector is the fact that possessing an unlocked iPhone will typically result in the thief having access to both email and SMS. Even without access to a third-party password manager, having access to either / both of those (but especially email) will typically allow for most password reset processes.

I would think to completely avoid the possibility of having financial accounts being accessible from a stolen phone + passcode would involve either not being logged into an email app with an account connected to the related accounts (perhaps only accessing those accounts through an incognito tab), or to use an email app which has a separate authentication (i.e. that doesn’t fall back to the phone passcode) step before emails can be accessed.

Same story for text message authentication — using a Google Voice number only accessed through the web interface would prevent the attacker from being able to successfully reset any passwords that way.

Not directly related to the topic, but the ability to recognize and grab text is quite good lately. Yesterday I took a photo of my home router, at a bad angle, in bad light, and grabbed Japanese text for a light I didn’t recognize and was able to paste it into Google Translate and find out what it meant. Pretty amazing.

doug

I keep credit card and password info in PasswordWallet. Maybe it’s older than 1Password, but I find it quite easy to use to enter passwords when I need it. Syncing between devices sometimes requires a manual sync step though. The developer is quite helpful whenever I have had problems.

Very important:

Apple allows a user to remove or change the screen time passcode using the Apple ID and then mstarting the “forgot pwd “ flow in screen time. Thief must know the Apple ID email which can be obtained if the user has a Family set up (just under iCloud name at the top of settings) or by opening email apps.

At the end the ID gets reseted again with the passcode.

This way locking with screentime is completely useless.

Also using the new hardware keys is useless. I tried it, via screen time , delete screen time code, lost ID, they won’t ask for the keys.

Means at the moment there is no workaround.

Also interesting, if you use the new hardware keys. If you know the device pin , you can just remove the keys. The os won’t ask for the keys or any password.

Didn’t Apple stop this, so that even turning-off the phone doesn’t stop Find My tracking now – as literally doing any of these was stopping the point of the service. Sure I guess if the thief stops cellular service somehow then that’s it (one reason to use eSIM, as that can’t be physically removed), but at least turning the phone off (with the extra battery they keep in reserve), isn’t meant to stop Find My.

Right, for relatively newer phones. (Since iPhone 11 I think?)

But accessing the control center from the lock screen and turning on airplane mode will stop find my from sharing your location (unless the person who has the phone brings it to a place where WiFi will connect.) And the attack I was mentioning - somebody in a crossroad, or a sidewalk, actively using an unlocked phone, stolen from their hand by a passing bicycle or scooter - the phone is unlocked. The thief doesn’t know the passcode, but they can turn on airplane mode, turn off wifi, etc., quite quickly as long as they do so before the device display times out.

If the phone never connects to a network, find my won’t reveal the location. Thankfully these people are protected from this particular attack mentioned in the WSJ - changing the Apple ID from the device - because they don’t know the passphrase.

The discussion is implicitly invoking the “Swiss Cheese” model of security, where there are multiple layers of protection, each with its own holes, but if the holes don’t line up, then one layer will protect against an attack that another layer will let through. The danger is if the holes all line up (as they do with the way Apple uses the passcode).

But it also occurs to me that some layers are more important than others, at least in terms of threat & inconvenience. The first layer is to protect against the phone getting stolen at all. If it doesn’t get stolen, then none of the other risks materialize. That makes it the most important layer to worry about. The second layer, unlocking the phone, is the second most important. If the thief can’t unlock the phone, then all the owner has lost is the phone itself.

I’d rather have Apple (and people) focus on hardening those first two layers than get obsessed with the ones further down. There are ways to do it: have the screen reduce brightness and contrast when you’re entering the passcode to make it harder for people to see from a distance; have the numbers on the screen be randomly scrambled so people can’t “read” your motions when you type them in. Etc.

For people, being aware of using the phone in public is critical. Don’t use it in such a way that you’re vulnerable to having it snatched. Don’t store it in an obvious place that is accessible when you’re not paying attention. Etc. etc.

I know you’re not suggesting these are actually implemented. But I want to point out to anyone who thinks they’re a good idea that either of these would make the phone unusable for a sizeable portion of the population. The most likely effect would be for many people to disable a passcode altogether. What looks like a security improvement might turn out to be the opposite on a population level.

Very good point – as always, Apple would have to balance security vs. usability (and not just general usability, but usability for specific communities).

These could be non-default options for people who might want better security. Advanced Data Protection is an option, and Apple makes it clear when you turn that on that they cannot help you recover the account if you forget the password and lose the recovery keys; why not add an option to prevent resetting the Apple ID from a device with just the passcode from that device? There is, in fact, an option on MacOS to allow or prevent using the Apple ID password to reset the user account password. Why not this level of control on iOS in the Apple ID settings?

Yes, I know that sometimes there seem to be too many options, but after the WSJ article detailing this vulnerability (to losing control of your Apple ID just by a thief knowing the device passphrase), it seems like a worthwhile option to me.

I think because the people who would take advantage of the options are already keeping things extra secure. I’d prefer a simple universal solution that ups the security level for everyone (it even helps those extra secure people because if thieves know that every iPhone is pretty darn secure, it reduces the incentive to steal any iPhone).

Agreed! Another idea I like is trying to avoid asking for the passcode unless the iPhone is in a known location, like Home or Work. Obviously, that won’t work all the time, but anything Apple can do to reduce the likelihood that a passcode is typed in public, the better.

Looks like Apple is planning to block the majority of these problems.