TidBITS#1138/13-Aug-2012

As we head into the third week of Mountain Lion’s reign, we look in more depth at aspects of Apple’s latest big cat that are causing confusion. Glenn Fleishman and Jeff Carlson lead off with a look at the Caller ID feature of Messages (in Mountain Lion and iOS), which controls the account to which replies will be directed. Then, very much on the same path, Joe Kissell tries to run down exactly what account Apple Mail will use when creating or replying to messages. Lastly, Matt Neuburg sets his laser sights on the Modern Document Model in Mountain Lion, explaining how it’s different from — and better than — its equivalent in Lion. Notable software releases this week include Nisus Writer Pro 2.0.4 and Express 3.4.3, DEVONthink and DEVONnote 2.4, and TextExpander 4.0.1.

Caller ID in Messages Helps to Direct iMessages

The Messages app in OS X 10.8 Mountain Lion confuses the heck out of us because we never know where a given iMessage we send or receive will wind up. Some people are irritated at having an incoming message pop up on an iPhone, iPad, and multiple Macs all at once. There’s no hope for that, as Apple doesn’t yet let you set a single incoming device for iMessage based on where your eyeballs are focused at the moment.

But the contrary problem is also baffling: what if you can’t get iMessages to appear on all your devices registered with the same Apple ID? We figured out the issue, which can let you both turn on that “feature” or disable it. The key is “Caller ID,” a preference that appears when you have multiple addresses registered in Messages in Mountain Lion or in iOS. (For an iPhone, the phone number counts as an address, so even a single email address produces this option.)

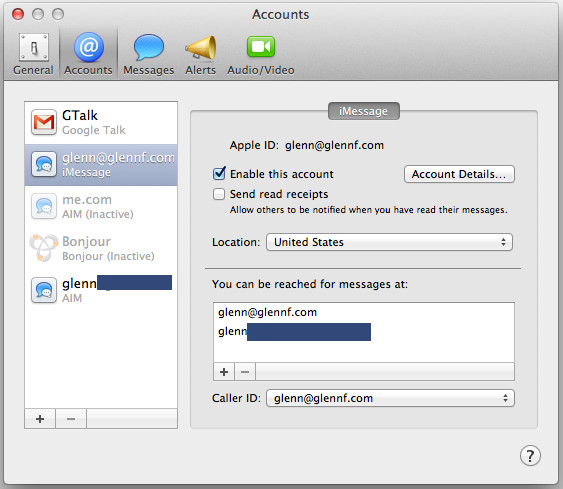

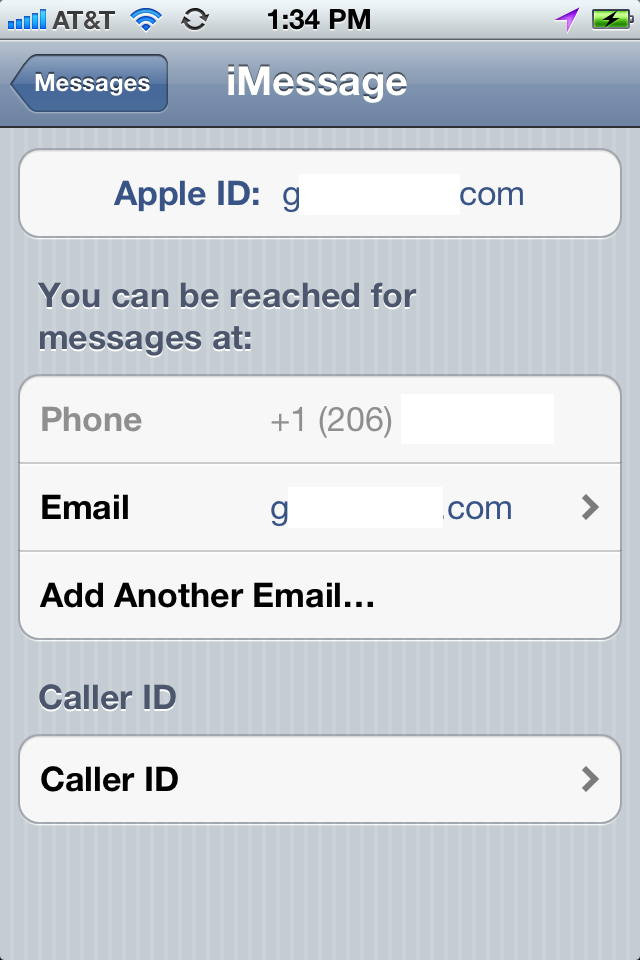

In Mountain Lion, you find the Caller ID setting in Messages > Preferences > Accounts: select your iMessage account, and the Caller ID menu appears at the bottom if multiple addresses are registered. In iOS, look in Settings > Messages > Receive At > Caller ID to find it.

Caller ID defines what the iOS and Mountain Lion Messages apps use as the implicit “from” address when sending an iMessage to another party. When the other person replies, her reply is directed to your Caller ID address. That’s straightforward enough. But where it gets tricky is when you have a

different set of email addresses associated with each iOS device and Mac.

For instance, let’s say Jeff has [email protected], [email protected], and [email protected] all associated with Messages in Mountain Lion on his MacBook Pro. On his iPhone, he has just [email protected], and on his iPad, just [email protected]. (This isn’t just hypothetical; in the process of testing, he realized that he’d set up each device with different addresses.)

If Caller ID on Mountain Lion has [email protected] selected, when he sends a text using Messages, the reply will return only to his Mac. If Jeff changes Caller ID to his [email protected] address, then responses come to his Mac and iPhone; if it’s changed to [email protected], then to his Mac and iPad.

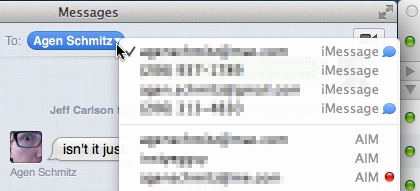

Now, Glenn can send Jeff an iMessage to any of those three email addresses, and the note will come in to his Mountain Lion chat window. But when he replies, Messages in Mountain Lion always changes the from address back to his Caller ID address. If Glenn, in turn, replies to that reply and doesn’t change the recipient address, his responses go just to the devices associated with that email address. (In Messages, in the Messages window, you can hover over the person’s name after the “To:” label in a Conversation, and then click the downward-pointing arrow — not the name — to switch the account to which you want to address a message.)

This provides you with a couple of possibilities.

- You can ensure that all devices receive all messages, by either making sure the same email addresses are entered or setting the Caller ID on each device to a common email address. For the moment, this is the most sensible approach for most people.

- You could set up device-specific iMessage accounts and mark each as the Caller ID sender for its particular device. This is a little absurd, but it would work for enabling you to receive an incoming message on all devices, but have subsequent replies directed only to a particular device. For example, Glenn could set up [email protected] on each of his devices, so iMessages to that address would show up everywhere. But, if the Caller ID address for his Mac was [email protected] and his iPhone was [email protected], responses to his iPhone-generated replies would come back solely to the iPhone. Similarly, when he initiates a conversation from a given device, his recipient doesn’t need to know that’s where it comes from;

they just reply.

Of course, this second approach highlights one of the main frustrations with iMessage. If someone stores this device-specific address and creates a new message later — instead of replying to Glenn’s last message or using his general iMessage address — they may send it to a device he’s not using! Also, only iPhones can use a phone number as an iMessage account, so it’s entirely possible that a friend will send a text to Glenn’s phone number and ignore any previous iMessage conversation, thus forcing the conversation to go only to his iPhone.

So, although you may have a small measure of control over which address is sent with your outgoing messages, you still can’t dictate how other people always send messages to you without relying on just one address for all devices.

This all serves to demonstrate the missing pieces in iMessage. Apple seems to not want to provide centralized management of email associated with accounts, leaving that up to the individual device. But Apple does validate email addresses that are used with iMessage centrally, and confirms that each non-Apple ID address is associated with only one Apple ID account at a time. A little bit of help in clarifying what goes where, even if we need a Web site or preference pane to manage the information, would eliminate a lot of confusion and unnecessary fiddling.

Mountain Lion Mail Perturbs Sending Behavior

Since the publication of “Take Control of Apple Mail in Mountain Lion,” several people have asked me about changes in the way Mail in Mountain Lion handles the From address in outgoing messages. At first I didn’t know what to say, because I hadn’t seen anything surprising in my own testing, but as more and more complaints have poured in (including many in Apple’s discussion forums), it became clear something was screwy. So I set out to investigate. It turns out Mail in Mountain Lion does handle outgoing mail differently than before, and for some users, it can be frustratingly difficult to predict what account Mail will send messages from.

Apple Mail lets you set up as many different accounts as you need, each with its own outgoing mail server and one or more associated email addresses. When you create a new message or reply to an existing message, Mail picks a default From account for you, although you can choose a different account from a pop-up menu in the header area of the message. That’s all entirely appropriate, and has been the case for as long as I can remember.

However, in Mountain Lion, Apple significantly changed the rules by which Mail chooses the default From account for outgoing messages. As a result, if you don’t carefully (and manually) check each outgoing message, you might find that you’re sending messages from an unintended account. This can have serious consequences if, for example, you end up sending work email from a personal account or vice-versa. I didn’t notice this during my first couple of weeks using Mountain Lion because I nearly always send email from the same account, and I don’t lose any sleep if I accidentally send mail from a different address. But for many users, this change is a big deal.

How exactly has the behavior changed? Here’s what I’ve found, based on well over 100 experiments covering as many combinations of variables as I could think of.

In Lion and earlier, the behavior is as follows:

- When replying to messages, Mail always sends replies from the account to which the message was addressed. This is true regardless of your preferences or where the message was stored.

- When composing new messages, Mail uses the account specified in the Send New Messages From pop-up menu on the Composing preference pane (in other words, exactly what the command says). The default choice, Account of Selected Mailbox, means that the account associated with whatever mailbox is currently selected in Mail’s sidebar is the one that should be used for outgoing messages. However, if a local (On My Mac) mailbox is selected, or if no mailbox at all is selected, Mail chooses a From account according to some rule I’ve been unable to nail down, even after many tests. And, if you have a particular message selected, then regardless of where it is, Mail may choose yet another From account — again, without

any immediately obvious logic.

In short, although Lion has some indeterminacy with the Account of Selected Mailbox setting, the behavior is mostly predictable — and when it comes to replies, it’s both consistent and logical.

On the other hand, in Mountain Lion, here’s what I’m seeing:

- When replying to messages:

- For messages stored in a server-based (e.g., IMAP or iCloud) mailbox, Mail uses the account associated with that mailbox — regardless of the account to which the message was sent or your preferences. That makes reasonable sense as far as it goes, and even though it’s different from before, it should yield the same result most of the time. But…

-

For messages stored in a local (On My Mac) mailbox, if Account of Selected Mailbox is chosen in the Send New Messages From pop-up menu on the Composing preference pane (as it is by default), Mail uses… um… some seemingly arbitrarily selected account. As with composing new messages in Lion, I’ve tried dozens of tests, and every time I think I’ve guessed the pattern (such as the topmost account enabled in the Accounts preference pane; iCloud first, then Gmail; the last account you sent mail from, etc.) I find an exception. I truly don’t know; all I can say is that Mail seems to pick the same account consistently as long as your account preferences remain unchanged. On the other hand, if a single account is specified in the

Send New Messages From pop-up menu, Mail uses that account — regardless of the account to which the message was sent. (In other words, it treats replies the same way as new messages.)

-

When composing new messages, Mail uses the account specified in the Send New Messages From pop-up menu on the Composing preference pane. As in Lion, Account of Selected Mailbox is the default choice, and for server-based mailboxes, it appears to work the same way. But if no mailbox is selected, or if a local (On My Mac) mailbox is selected, Mail uses the account whose Inbox appears first (under the unified Inbox in Mail’s sidebar); you can drag Inboxes up or down in this list to change their order.

To illustrate why this might be a serious problem, consider a user who has three different POP accounts — say, a home account, a work account, and a family account. Messages from all those accounts are filed into various local mailboxes, perhaps automatically by rules. When it comes time to reply to one of these messages, the user should be able to count on the fact that the reply will be sent from the same account that received it, without further intervention. That used to be the case, but it isn’t now. So outgoing messages may be missed or discarded because they come from the wrong account, messages can cross between business and personal domains, and so on.

I have no idea why Apple made this change, whether it was intentional, why it wasn’t documented, or whether it might be changed back in the future. Because the change might have been deliberate, and might have happened for some good reason that I simply can’t discern, I hesitate to label it as a bug. But in any case the change requires more thought and effort for users, and on the whole I think it was a pretty bad move. If you think so too, choose Mail > Provide Mail Feedback and share your thoughts on the matter with Apple. We can only hope Apple changes this in an update to OS X.

In the meantime, I’m sorry to say I know of no way to return Mail to its pre-Mountain Lion behavior. Choosing a single account from the Account of Selected Mailbox pop-up menu will keep Mail’s behavior fairly consistent, although that may not suit your needs. Likewise, using only server-based mailboxes, if you can do so, avoids the most serious part of the problem. Apart from those admittedly weak suggestions, I can’t offer any advice other than to be aware of the change and remain vigilant when sending messages.

One final tip, courtesy of Christopher Stone on the TidBITS Talk mailing list: In Mountain Lion, you can assign a keyboard shortcut to change the From account of the message you’re currently composing, which may be slightly easier than using a mouse or trackpad to choose the account from the From pop-up menu. To assign a keyboard shortcut, open the Keyboard pane of System Preferences, click Keyboard Shortcuts, and then select Application Shortcuts. Click the + (plus) button and select Mail from the Application pop-up menu. In the Menu Title field, type the exact name and email address as they appear in the From pop-up menu — for example:

Joe Kissell <[email protected]>

Enter the keyboard shortcut you want to use and click Add; repeat if necessary for multiple accounts. The next time you’re composing a message and realize you want to switch the From account, press the corresponding keyboard shortcut.

The Very Model of a Modern Mountain Lion Document

In the recently released OS X 10.8 Mountain Lion, Apple has done something I thought they’d never do: they backtracked — sort of. They heeded the objections of users to a major feature of 10.7 Lion, and took steps to meet those objections. They didn’t remove the feature — that, I suppose, would be asking too much — but they changed the interface and provided an increased range of user choices and capabilities.

In this article, I’ll sketch out how Mountain Lion is different from Lion with regard to this feature, and why, therefore, I personally like Mountain Lion much more than Lion. For more detail, and for lots more about Mountain Lion, see my book, “Take Control of Using Mountain Lion.”

The Lion Situation — The feature in question, which Apple calls the Modern Document Model, is the way documents are saved and handled by applications that have been appropriately rewritten to adopt certain technologies introduced in Lion:

- Auto Save, the heart of the Modern Document Model, means that documents open in these applications save themselves automatically as you edit them. You can still save a document explicitly; but you can, in theory, work with a document in a Modern Document Model application without ever saving it explicitly — except, perhaps, at the outset, when you save a new untitled document to assign it a name and a place in the folder hierarchy.

In Lion, the black dot in the document window’s red close button, familiar to users from years of previous Mac OS X systems, never appears; a document is never “dirty” (in need of saving), because it is always being autosaved. Moreover, for the same reason, when the document is closed, no “Save changes?” dialog appears. (There’s one exceptional situation where such a dialog does appear in Lion, which I’ll describe in a moment.) The word Edited appears in the title bar of a document that has been changed since it was opened or explicitly saved, but many users don’t find this a sufficiently strong cue.

- Resume is the capability of an application, when launched, to reopen automatically all the windows (especially documents) that were open when that application was running previously. Lion allows you to toggle this behavior globally or when quitting a particular application (though, as I pointed out in “Lion Zombie Document Mystery Solved,” 23 May 2012, under certain circumstances an application’s windows might be resumed on launch even when you’ve set them not to be). Resume is tightly integrated with Auto Save; with both of them operative, Mac OS X is clearly trying to imitate iOS, where ideally one should not be able to tell the difference between switching to an app

and relaunching it after it has been terminated.In Lion, if you quit a Modern Document Model application with a new untitled document still open, that document is automatically saved (Auto Save) and automatically reopened the next time the application runs (Resume), regardless of your Resume settings. But if you close a new untitled document explicitly (with File > Close or by clicking the window’s close button), a dialog appears (“Do you want to save…?”) where you can either save the untitled document or dismiss its unwanted contents once and for all.

-

Versions is the capability of the system to record the current state of an autosaved document so that you can later retrieve that state. To some extent, such states are maintained automatically. Additionally, in Lion, once a document has been saved (so that it is no longer a new untitled document), the File > Save menu item is replaced by File > Save a Version; the document is being autosaved constantly, of course, but choosing Save a Version not only saves, but also causes this particular state of the document to be stored in the Versions database.

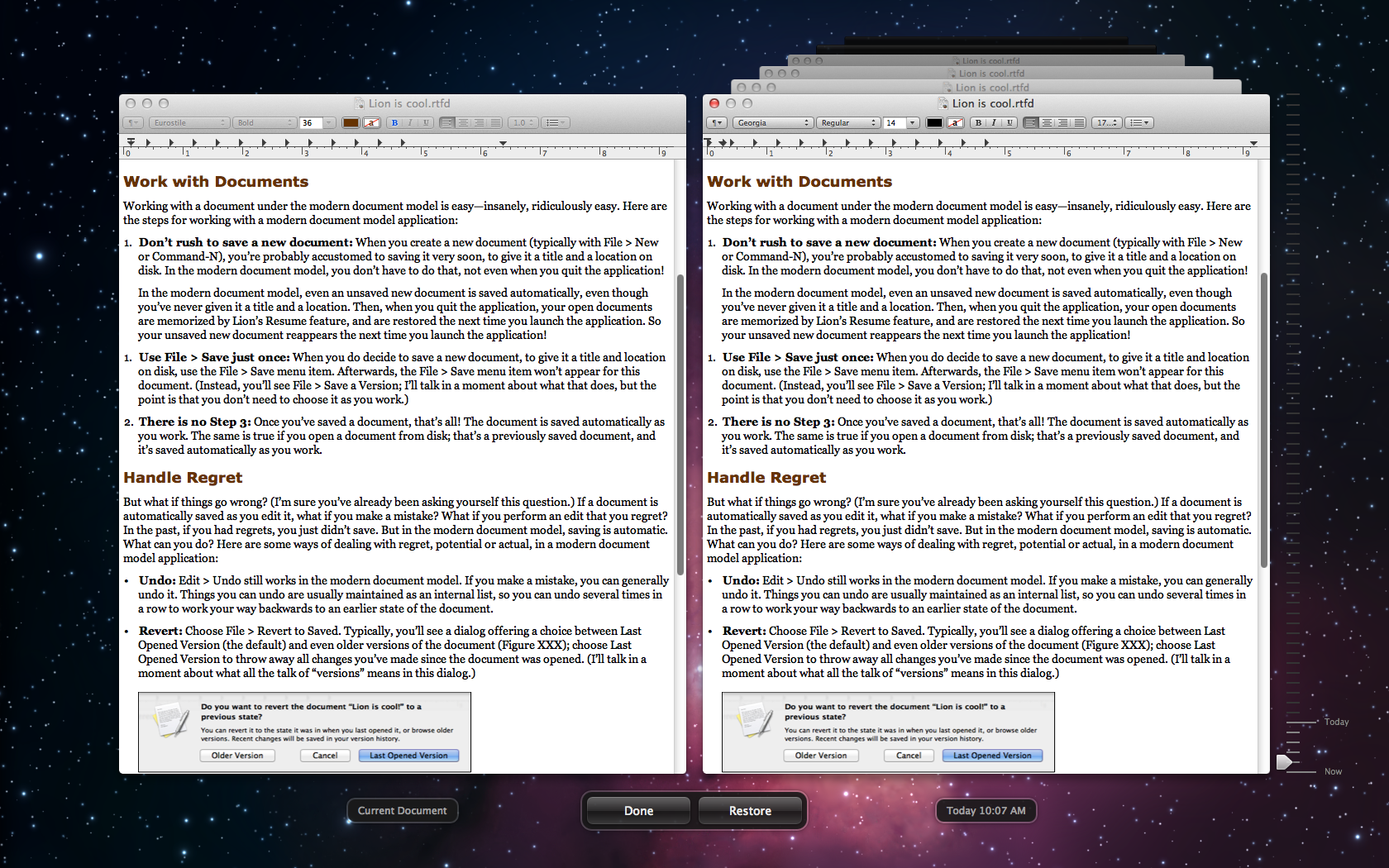

In Lion, access to the Versions database is chiefly through the File > Revert Document menu item, which brings up a Time Machine-like interface showing all saved states of the document. One particular document state — the state of the document when last opened or last saved — might also be accessible by choosing from the document’s title bar menu.

-

The File > Save As menu item, to which users have been accustomed since System 6 (or before), is absent in Lion. In the case of a new untitled document, it is redundant, since File > Save performs the same function, giving the user the opportunity to assign the document an initial name and folder location. In the case of a previously saved document, its functionality is replaced by that of File > Duplicate, which copies the current document’s state into a new untitled document, without closing the original document. The user can then save this new document (giving it a name and folder location).

The Trouble With Lion — Lion’s Modern Document Model constituted a revolution in how users had to work with documents through applications, and for many users, it wasn’t a revolution they liked. Unlearning the habit of saving whenever you think of it, lest your work be lost if the application crashes, was easy; the heart of the problem had more to do with accidents.

Who hasn’t quit an application, supposedly without having altered a document, only to see the “Save changes?” dialog appear unexpectedly? It turns out that you did alter the document, but by mistake; you thought you were copying, perhaps, but you cut instead, or the cat prodded the keyboard while an important paragraph was selected. That dialog warned you, and rescued you, letting you cancel those unintended changes. Under Lion, there is no dialog and no warning; your accidental changes are saved without your knowledge and possibly contrary to your desires.

Auto Save in Lion, users objected, was thus a potential trap, an invitation to cause the very thing it was supposedly designed to prevent — accidental data loss. The data might not really be lost, since the Versions database might hold an acceptable earlier state of the document; but finding that state in the clumsy Time Machine-like interface wasn’t easy. And what if, after saving a problematic change that you weren’t even aware of, you closed the document and didn’t return to it for days, perhaps weeks, opening it later only to be horrified and confused? Would Versions help you understand what had happened? Would the database still contain the desired document state? It all seemed so backwards, somehow: first make a

drastic accidental mistake, then later discover it (if you’re lucky) and scurry around trying to fix it — whereas, prior to Lion, you would have been alerted before making the mistake of saving the faulty document in the first place.

Then there’s the matter of experimentation. Who hasn’t deliberately played with a document experimentally, knowing that no harm would be done if things went wrong, since you could easily close without saving at the end, or spawn off your unsaved changes into a different document with Save As? Now Lion comes along and saves your experimental changes behind your back and against your will. Lion doesn’t really prevent experimentation, of course; all you have to do is choose File > Duplicate, and now you’re working in an unsaved copy of your document, which you can ultimately close without saving. But here again, things seem to be backwards, since you must remember to choose File > Duplicate before you

experiment; you might easily forget to do that, or you might not realize, until it’s too late, that your changes are undesirable.

Mountain Lion to the Rescue — What Mountain Lion brings to the Modern Document Model mix are two checkboxes, in the General pane of System Preferences, that affect the behavior of applications when documents close, along with some new menu items. Let’s start with the two checkboxes:

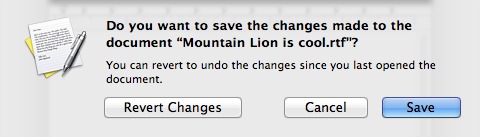

- “Ask to keep changes when closing documents.” If this checkbox is unchecked, Mountain Lion behaves like Lion. If checked, though, Mountain Lion behaves more like Snow Leopard and before: The close button’s “dirty” dot returns! The warning dialog appears when you close a “dirty” document! So, in Mountain Lion, the chances are not as great as in Lion that you might accidentally keep unintended changes in a document.

Note, however, that this checkbox does not turn off Auto Save; your document is still being saved automatically behind the scenes! The warning dialog asks “Do you want to save the changes…?” and its default button is labeled Save; but in fact the document has already been saved, and what you’re really deciding is whether to keep those saved changes or to revert the document to an earlier state (preserved, of course, in the Versions database). So Auto Save is still operative, but the

interface gives the illusion that it isn’t. -

“Close windows when quitting an application.” This second checkbox is a little tricky, in that it actually does two things: (1) it determines whether Resume is turned on or off globally, and (2) it determines whether quitting an application counts as closing its documents, as far as the first checkbox is concerned.

To see what I mean, suppose first that this second checkbox is unchecked. Then when you quit an application with open document windows, those windows just vanish with no warning dialog, even if they represent “dirty” documents. In a way, by unchecking this checkbox, you’re saying: “Quitting an application is different from closing its document windows one by one. When I say quit, I mean quit now, without waiting around for any dialogs.” This is true even if the first checkbox (“Ask to keep changes when closing documents”) is checked — because, according to this second checkbox, quitting an application doesn’t actually count as closing its documents! Instead, the state of those documents is automatically saved

(Auto Save), and the documents will be opened again automatically (Resume) the next time the application launches. (Note that if the first checkbox is checked, then when these documents are automatically re-opened, their “dirty” state is remembered from when they were closed: if they were “dirty” when you quit the application, they reopen with the “dirty” dot still present in the close button.)If, on the other hand, this second checkbox (“Close windows when quitting an application”) is checked, then when you quit an application with any “dirty” document windows open, those windows fall under the power of the first checkbox (“Ask to keep changes”). So, if the first checkbox is also checked, then when you quit an application with a single “dirty” document window, you’ll see the “Save changes?” dialog, and when you quit an application with multiple “dirty” document windows, you’ll see the familiar Cocoa dialog asking: “You have … documents with unconfirmed changes. Do you want to review these changes before quitting?”

Moreover, if this second (“Close windows”) checkbox is checked, Resume is globally turned off. But let’s say that you hold Option while quitting. This turns on Resume temporarily, and things then work as if this checkbox were unchecked: you’re saying, “Quit now, darn it!” So the application quits instantly, even if the first checkbox is checked, and even if some open windows are “dirty” documents (and, the next time you launch the application, those windows are reopened automatically and their “dirty”

state is remembered).

In addition, Mountain Lion’s Modern Document Model provides the following menu items:

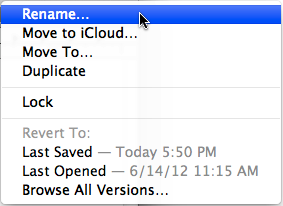

- File > Save is now always File > Save; it doesn’t change to File > Save a Version. Of course, saving a previously saved document does still save a version; but the unchanging menu title simplifies things.

-

In addition to File > Duplicate, which is still present from Lion, the File > Save As menu item is back; in fact, the latter is an alternative to the former (hold Option to see it). This gives users a choice of working in whichever way feels comfortable and appropriate to the circumstances. File > Duplicate copies the current document as a new untitled document, leaving the current document open behind it; File > Save As, similar to pre-Lion systems, lets you create a copy of the current document with a new name and location, with the document window showing the copy rather than the original.

-

File > Revert To (instead of Lion’s File > Revert Document) is now a hierarchical menu item: its subitems, depending on the circumstances, may include Last Opened, Last Saved, and Browse All Versions, thus focusing on the most common use cases and clarifying your options.

-

Last but not least, there are two completely new menu items in Mountain Lion. File > Rename lets you rename a document in place; File > Move To lets you move a document to a different folder. These are actions that previously you might have performed on a file from the Finder; now you can perform them on a document directly from within the application that has the document open. Both these menu items are so useful that one is left wondering how we lived without them in previous systems.

All of these menu items are present not only in the File menu but also in the document window’s title bar menu — except, oddly, for Save As, which is thus unfortunately reduced to second-class status and is unnecessarily difficult to discover.

(I should also mention one further change. In Lion, a document would be locked automatically if it wasn’t edited for some amount of time, such as two weeks; in Mountain Lion, this autolocking behavior has been withdrawn. You can still lock a document by choosing Lock from the title bar menu, but this is no different from the capability the Finder has always had to let you lock a document.)

Conclusions — For me personally, these changes have made Mountain Lion usable and acceptable in a way that Lion was not; and I expect that many users will feel the same way. I’m particularly impressed with Apple’s willingness to provide users with options, something that in the past I’ve frequently called upon them to do. The two General preference pane checkboxes enable users to make Mountain Lion either keep on behaving like Lion or simulate the pre-Lion document behavior with which they may feel more comfortable and confident. Similarly, I like being able to choose File > Duplicate or File > Save As, depending on the nature of the task at hand. And I think

Apple’s rejiggering of the File menu items, especially the new Rename and Move To items, is just splendid.

Please note, though, that I’m not claiming to be entirely happy with the Modern Document Model. Actually, to be quite honest, in my view, Auto Save is itself a massive mistake, an utterly erroneous pretense that the desktop is like iOS. Its deeply flawed nature is well revealed by what happens when you edit a file on a mounted remote disk: you get Auto Save without Versions, which even Apple has admitted is troublesome; see Adam Engst’s article on this topic, “Beware Lion’s Versions Bug on Network and Non-HFS+ Volumes” (8 September 2011).

Also, complications are added by the presence in Mountain Lion of “Documents in the Cloud” — the capability of some applications to save their documents where iCloud can synchronize them. I don’t want to get into details here, but suffice it to say that if an application is iCloud-savvy, its various Modern Document Model warning dialogs and its Open and Save dialogs look different from those of an application that isn’t iCloud-savvy. We thus end up with a three-way “Balkanization of the desktop”: applications that don’t subscribe to the Modern Document Model, those that do but aren’t iCloud-savvy, and those that do and are iCloud-savvy. Each of these looks and behaves differently from the others (see my “Take Control of Using Mountain Lion” for details).

While I’m in a complaining mood, I’d also like to mention my reservations about that second checkbox, “Close windows when quitting an application.” As I’ve said, this really does two things — it toggles global Resume on and off, and it changes whether quitting causes a document window to fall under the rubric of the first “Ask to keep changes” checkbox. But those two things, while related, aren’t strictly identical, and the title of the checkbox doesn’t describe either of them very accurately. The result is that it’s hard to understand just what this checkbox does; even the usually scrupulous John Siracusa seems to miss its full significance in his technical review of Mountain Lion, and I myself accidentally omitted part of the story in my Take Control book.

And Apple hasn’t quite implemented the first checkbox correctly, either. It says, “Ask to keep changes when closing documents,” but if you open and edit a document and then choose File > Save As (surely the most common use case for Save As), the original document is effectively closed without asking you about those changes; the new file contains the unconfirmed changes, which makes sense, but so does the old file, which is clearly a violation of your request to be asked about changes. Oddly, this is something Lion did somewhat better than Mountain Lion: in Lion, when you chose File > Duplicate on an edited document, you got a dialog offering a chance to revert before duplicating; that dialog no longer appears in Mountain

Lion.

However, all of that aside, I would still submit that the changes to the Modern Document Model in Mountain Lion are welcome, ingenious, and extraordinarily significant. I would still prefer a way to turn off Auto Save altogether; but if we stipulate that Apple will never allow that, they have bent over backwards to make Auto Save acceptable to a lot more users, even if they still haven’t got everything quite right. I cannot sympathize with an attitude like that of David Pogue, who, in his New York Times article introducing Mountain Lion, rightly calls Lion’s Auto Save “baffling”, but then

dismisses the Mountain Lion changes to the Modern Document Model as consisting only of a couple of menu items and assigns them a negative value. Those changes are the main reason, I argue, for preferring Mountain Lion to Lion, and might even entice users who never really updated from Snow Leopard to Lion (in which number I include myself) to make the switch to Mountain Lion more or less full-time.

TidBITS Watchlist: Notable Software Updates for 13 August 2012

Nisus Writer Pro 2.0.4 and Express 3.4.3 — Though both of its word processing apps were recently updated with numerous changes, Nisus Software has released Nisus Writer Pro 2.0.4 and Nisus Writer Express 3.4.3 to fix some commonly reported problems. When running OS X 10.8 Mountain Lion, both apps now display Apple’s Start Dictation menu command in the Edit menu and fix a crash that occurred when right-clicking the style list in stylesheet view. Additionally, both apps ensure correct hyphenation for non-English languages, correct a problem with clipping and zooming in the Print dialog preview,

fix issues with links to files, and fix a problem with an “ungraceful” flickering redisplay that occurred when zooming in and out of Draft View. For just Nisus Writer Pro, version 2.0.4 fixes an issue when exporting a document with special characters to EPUB format, prevents a hang when copying or pasting multipart selections with applied TOCs, and fixes an issue with changing the color of a style’s paragraph border or edge. (For Nisus Writer Pro: $79 new, free update, 159 MB, release notes. For Nisus Writer Express: $45 new, free update, 51 MB, release notes.)

Read/post comments about Nisus Writer Pro 2.0.4 and Express 3.4.3.

DEVONthink and DEVONnote 2.4 — DEVONtechnologies has updated all three editions of DEVONthink (Personal, Pro, and Pro Office) plus DEVONnote to version 2.4, bringing compatibility with the new features of OS X 10.8 Mountain Lion. In particular, the releases support Notification Center, play nicely with Gatekeeper, and add a share button for sharing documents via iMessage, Mail, Twitter, Facebook, and AirDrop (as well as adding them to Safari’s Reading List). With added 64-bit support, database sizes are now bound only by the available

memory and performance of your Mac. All three versions of DEVONthink can now import scans and images from scanners and cameras that are compatible with Image Capture (including iOS devices). Previously, this feature was available only in the Pro Office version. (All updates are free. DEVONthink Pro Office, $149.95 new; DEVONthink Professional, $79.95 new; DEVONthink Personal, $49.95 new, release notes; DEVONnote, $24.95 new, release notes)

Read/post comments about DEVONthink and DEVONnote 2.4.

TextExpander 4.0.1 — Smile has released TextExpander 4.0.1, a maintenance follow-up for the recently updated typing shortcut utility with a modicum of fixes and improvements. The release restores transparency to the menu bar icon, makes the checkbox label clickable for optional section fill-ins, and updates its help section for Japanese and Italian localizations. Additionally, equality abbreviations in the Symbol group now end with two equal signs (such as “>==”). It’s rounded out by many other unnamed minor fixes and improvements. ($34.95 new with a 20-percent discount for TidBITS members, $15 upgrade (free for purchases after 15 January 2012), free update, 8.5 MB)

Read/post comments about TextExpander 4.0.1.

ExtraBITS for 13 August 2012

HyperCard was released 25 years ago, so we point at Twitter-linked reminiscences this week in ExtraBITS, along with Dan Frakes’s explanation of Mountain Lion’s new Power Nap feature and more on how Mat Honan’s iCloud account was hacked (the specifics of which should no longer be possible).

HyperCard’s 25th Anniversary Reminiscences — On 11 August 1987, Apple released the “software erector set” HyperCard at Macworld Expo in Boston, and while it hasn’t been with us for many years now, back then it made a huge difference in the lives of Mac users, enabling many to give life to ideas that would otherwise never have seen the light of day. That might include even TidBITS, since we published our first 99 issues in HyperCard format, in a stack that could import its content into a searchable archive. Without the thrill of publishing in an entirely new format, it’s possible that TidBITS

might have fallen by the wayside. Scroll through what others have posted in this Twitter search, and be sure to check out Infinite Canvas on the iPad too!

Dan Frakes Explains Power Nap — Mountain Lion offers a new feature called Power Nap, but since it’s limited to only a few recent laptop Mac models, most people probably haven’t seen it. In short, Power Nap enables supported Macs to wake up briefly to back up via Time Machine, check for email via Mail, receive new messages in Messages, and update iCloud-related data, including calendar events, contacts, reminders, notes, iCloud documents, and photos in Photo Stream. Over at Macworld, our friend Dan Frakes explains just what Power Nap can do, how you use it, why it works on

so few models, and more.

How Apple and Amazon Security Flaws Led to Mat Honan Being Hacked — Gizmodo writer Mat Honan has penned an article for Wired that explains exactly how security flaws at Amazon (revealing part of a credit card number) and Apple (verifying identity using the Amazon details and other public information) led to much of his digital life being hacked. It’s a fascinating read, and our initial takeaway is that you absolutely must have local backups of all your data, whether on your Mac, your iPhone, or your cloud-storage accounts. Mat didn’t, and while the online disruption of his life

may be temporary, the data he lost from having his Mac wiped remotely is irreplaceable.

Apple and Amazon Change Security Practices — Details are still coming in, but Wired reports that the relatively simple hack that made it possible for Mat Honan’s digital life to be taken over remotely should not be possible anymore, with Amazon and Apple both changing account-related security practices, at least temporarily. What these policies will evolve to remains unknown, but both companies clearly needed to do something.