TidBITS#1375/03-Jul-2017

Mac app subscription service Setapp is now 5 months old — Adam Engst checks in to see how it’s doing and if it’s making developers any money. Speaking of money, Mike Matthews explores the question “Can your iPhone can replace your wallet?” Glenn Fleishman takes a deep dive into the details of the new HEVC and HEIF image formats coming to Apple’s operating systems, explaining how they’ll make a huge difference to streaming video and image storage. Finally, we welcome Jamf back as a TidBITS sponsor! Notable software releases this week include Transmit 4.4.13, Moneydance 2017.3, and MoneyWiz 2.6.

Jamf Now Sponsoring TidBITS

We’re pleased to welcome back as our latest long-term TidBITS sponsor Jamf Now, formerly Bushel, the cloud-based mobile device management (MDM) solution for Apple devices in the workplace.

What’s MDM? Put simply, it’s the automation of standard setup and maintenance tasks for iPhones, iPads, and Macs so when your company buys a new device, you don’t have to manually configure email, distribute apps, and enable necessary security settings.

Jamf Now is designed for small to mid-sized organizations that have outgrown manual configuration but aren’t yet at the size where the enterprise-level Jamf Pro is warranted for MDM. Much of the difference comes down to features and price — while Jamf Now offers only some of the core features that Jamf Pro does, it is much more affordable at $2 per device per month. And you can give Jamf Now a try for free with up to three devices.

Julio Ojeda-Zapata reviewed Jamf Now a couple of years ago when it was still called Bushel in “ITbits: Bushel Helps Small Companies Manage Apple Devices” (31 March 2015). He concluded that “it’s simple, easy to understand, and inexpensive — a perfect combination for allowing the part-time IT administrator to get back to her other tasks.”

That’s why I’m especially glad to have Jamf Now returning as a TidBITS sponsor — while there’s a lot more talk about social media and chat apps and games these days, I far prefer it when TidBITS can help people who use their Apple devices for productive work. If Julio’s hypothetical part-time IT administrator can tell her boss that she has rationalized all device management for less than $25 per year with Jamf Now after reading about it here, I’ll be happy.

Thanks to Jamf for their support of TidBITS and the Apple community!

Setapp At 5 Months: 10,000 Users and Better App Discovery

Early in 2017, I wrote about Setapp, an intriguing subscription service that provides access to a slew of carefully curated Mac apps for a $9.99 monthly fee (see “Setapp Offers Numerous Mac Apps for One Monthly Subscription Fee,” 25 January 2017). Just as Netflix does with video and Apple Music does with songs, Setapp’s pitch is that $9.99 per month ($120 per year) will be less than you’d spend on buying and upgrading apps individually.

Setapp Numbers — Nearly halfway through Setapp’s first year, it’s time to take a look and see how it’s doing. Most notably, the number of apps available to subscribers has grown from 60 to 77 (from 69 developers), providing users with lots more functionality without sacrificing quality or providing many nearly identical apps. No one would buy all those apps, of course, but if they did, it would cost $2437.

Julia Petryk of MacPaw tells me that Setapp now has 10,000 paying users and another 200,000 people who are using it in the free 30-day trial mode, which can be extended by encouraging a friend to sign up. Those aren’t Apple-level numbers, of course, but they’re respectable for just a few months.

I polled a few developers who are participating in Setapp, and although all of them remain optimistic about Setapp’s potential, Setapp hasn’t contributed significantly to the bottom line for any of them. Joe Japes of Econ Technologies estimated that the inclusion of ChronoSync Express in Setapp had increased revenues by less than 1 percent. Jesse Grosjean of Hog Bay Software told me that putting TaskPaper in Setapp had been a “nice but relatively minor boost” that generated about 5 percent of his monthly revenue.

On the plus side, Grosjean said the income from Setapp was increasing, and Japes noted that “the key for us is Setapp’s potential.” David Sinclair of Dejal Systems said he was quite pleased with Setapp and that Setapp “accounts for a significant chunk of new Dejal Simon customers.” He also pointed out that “Simon is a premium app, at $99, so offering an inexpensive subscription option for it alone makes a lot of sense for Simon users, and they get all those other apps as a bonus.”

Sinclair elaborated further: “I feel I’m making more money since Setapp than before. Some people might have purchased Simon directly instead of getting it via Setapp, but more people are discovering it via Setapp than before. I’ve had some people find Simon via Setapp but choose to buy it directly instead of continuing Setapp, but lots of people seem to prefer the subscription. It’s good to have both options. I think over time the revenue should be about the same for direct sales with paid upgrades every few years, compared to Setapp subscriptions.”

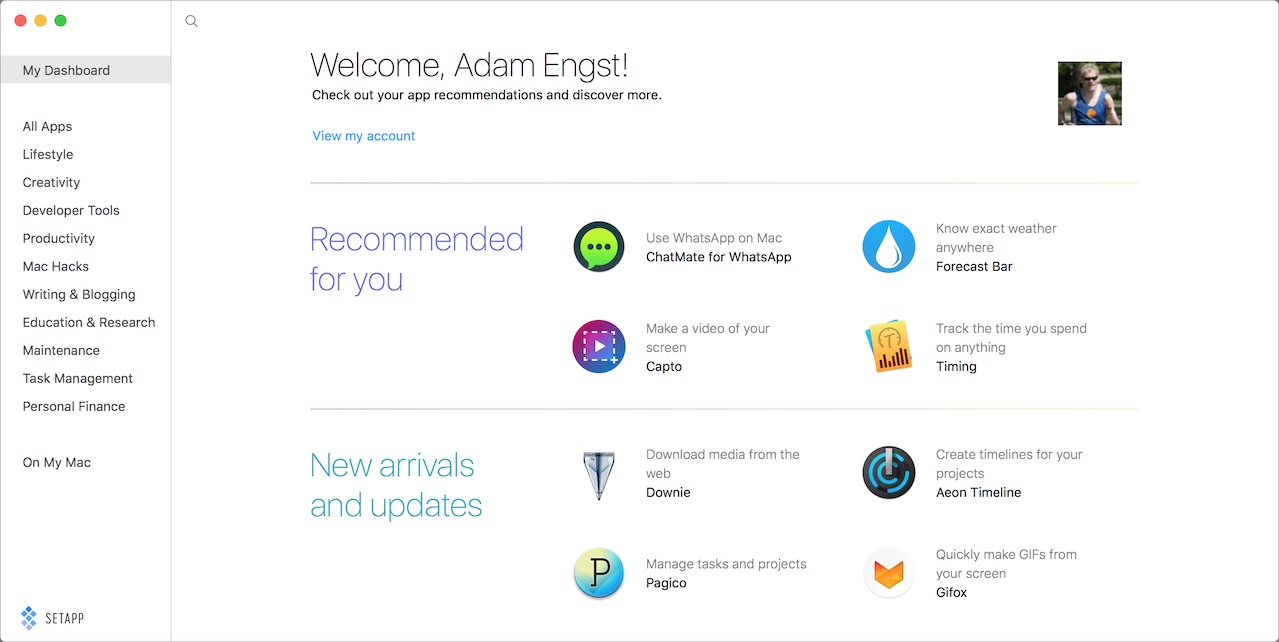

Setapp and App Discovery — The biggest problem Setapp faced initially — apart from simply being a new concept — was that of app discovery. With 60 apps at first, and now 77, how could you even figure out which apps you might want to use to solve a particular problem? In my introductory article, I noted that browsing through the apps listed on Setapp’s Web site was easier than opening each one in turn in the Finder. No longer.

MacPaw’s first swipe at this problem came a few months ago, when Setapp gained a catalog-like interface to separate all the apps into categories and call out those that you’d already installed. Each app received a brief summary and a full description, complete with screenshots.

That was a good step, but finding an appropriate app still took effort, so MacPaw went back to the drawing board and developed a recommendation system, which is rolling out to users now. It provides a My Dashboard entry above the app categories, and in it, recommends apps that you might want to try. The recommendation engine works by comparing the Setapp apps you’ve used against those used by other Setapp users and by finding apps similar to those you’ve already used. Even though it looks only at data within the Setapp ecosystem, the four apps it initially suggested for me were good guesses:

- Forecast Bar provides hyper-local weather information in your Mac’s menu bar. I love Dark Sky on the iPhone and Forecast Bar looks like it will give me single-click access to similar information on my Mac. I installed it immediately.

- Capto from Global Delight is a capable screenshot and video capture utility for the Mac. I prefer macOS’s built-in screenshot capabilities coupled with editing in Preview, and I usually use QuickTime Player for screen recordings, but it was a good recommendation.

- ChatMate for WhatsApp isn’t something I have much interest in, purely because I don’t use WhatsApp for messaging, but since I do use Messages, Google Hangouts, Skype, FaceTime, and more, it’s not a bad suggestion.

- Timing looks like a useful time-tracking utility, and since I’ve long had RescueTime installed and have just started testing Qbserve, it’s also a good recommendation. Perhaps I’ll have to do a three-way comparison.

Also on the My Dashboard screen are new arrivals and updates, which help you stay aware of how Setapp’s collection is expanding and improving over time.

Setapp for Users and Developers — Does SetApp make sense for users? It’s a great way to sample a lot of apps, even if you aren’t going to use that many of them in your everyday routine. In fact, I’d suggest that much of the value comes in apps you need to use only infrequently and thus wouldn’t buy. Julia Petryk of MacPaw said that the average Setapp user installs 10 to 12 apps.

For instance, the only app in Setapp I use all the time is iStat Menus because I like its menu bar performance graphs. But I’ve used Gemini to eliminate duplicate files a few times and Permute to convert video files to other formats. At a conference, I saved another speaker’s bacon by using Downie to download a YouTube clip so he could embed it into his Keynote presentation. I checked out iMazing to answer a reader’s questions about extracting SMS text message conversations and voicemails from an

iPhone. I also tried SQLPro Studio but decided that for what I need, the open-source phpMyAdmin is fine.

The beauty of Setapp for users is that it’s entirely optional, so if you feel it offers sufficient value for your $9.99 per month, give it a try. And if you’re not a fan of subscriptions, stick to buying the individual apps you need.

If you’re a developer, should you try to get your app into Setapp? That’s a tougher question. As Joe Japes told me, you have to weigh the pros and cons to make sure that participating in Setapp won’t cannibalize sales. For higher-priced apps, as with Simon, the subscription might bring in enough new users due to the lower price point to make up for the loss in direct revenues. And it’s a way that you could add a subscription option without having to roll the technology yourself.

Remember, though, that MacPaw curates the collection. David Sinclair said, “I would definitely encourage other developers to consider signing up for Setapp, though MacPaw is very selective of the apps they accept, which is great for users, but can be frustrating for developers.”

Other SetApp developers with similarly low revenue increases expressed the worry that, as MacPaw brings additional compelling apps to Setapp, the per-user payout will have to be split between more developers.

So that’s a tension, then. From the user perspective, you want to take advantage of as many apps as you can to ensure you’re extracting the most value from your subscription. Each developer participating in Setapp, however, would prefer that you use their app and as few others as possible, so the revenues are shared between only a few developers. And MacPaw is in the middle, wanting both to bolster Setapp’s perceived value to users by adding more apps and to keep developers happy by increasing revenues.

No one ever said that rethinking an entire business model would be easy.

Can Your iPhone Replace Your Wallet?

Fans of the TV show “Seinfeld” might remember George Costanza’s overstuffed wallet, which he described as “an organizer, a secretary, and a friend,” complete with notes, receipts, hard candy, Sweet’N Low packets, and possibly even cash. Back in the 1990s, unless you carried a purse, or as Jerry Seinfeld called it, a “European carryall,” your wallet was often the repository for all that stuff you might need just in case, like George’s Irish money.

Thanks to the iPhone, you no longer need a wallet so large that you have to stuff napkins in the opposite pocket to level out your posterior. Your iPhone can store notes, photos, and receipts. And with Apple Pay, Apple has even bigger ambitions.

When Apple VP Jennifer Bailey, who leads Apple Pay, said at a Recode Code Commerce Series event in 2016, “Everything in your wallet, we’re thinking about,” she probably didn’t have Sweet’N Low packets in mind. But while I’m not using my wallet to squirrel away artificial sweeteners, I am looking forward to when I don’t have to carry around a wallet full of random cards that I might need sometime.

But how close are we, really, to that day?

Even before the debut of Apple’s Wallet app (when it appeared in iOS 6 as Passbook; see “Passbook’s Best Is (Probably) Yet to Come,” 20 September 2012), I had stopped trying to carry everything in my wallet. Begone, hotel membership cards. Away with ye, frequent flyer cards.

Back then, I replaced many such cards with a single, laminated card that held numbers for my hotel and airline accounts. That was helpful, but plenty remained.

What remains in my wallet now that I’m carrying an iPhone everywhere I go? My laminated card is gone, having been replaced by a password manager and iPhone apps for hotels and airlines (see “Comparing Five iOS Travel Management Apps,” 11 April 2017).

Still, there’s a lot left, and the collection probably looks a lot like yours. Let’s take a look at each category and see what the likelihood is that you’ll eventually be able to offload it to an iPhone app.

Cash — While it seems that Apple is printing money these days, that’s only in a metaphoric sense. But if you wanted to walk around with almost no cash and pay for nearly everything with some virtual payment scheme, you might be able to get away with it.

Apps such as PayPal, Circle, Square Cash, and Venmo allow people to pay for things or send cash to each other — Glenn Fleishman wrote about that last year in “Circle, Square, and Venmo: Payment Apps Let You Pay via iMessage” (3 October 2016).

The latest news, announced at WWDC, is that Apple itself will be getting into the payment game, adding person-to-person payments as a function of Apple Pay. The process will be initiated through an iMessage app and will use a virtual Apple Pay cash card when iOS 11 ships in a few months (see “iOS 11 Gets Smarter in Small Ways,” 5 June 2017). This change will be big, maybe bigger than George’s wallet. Never underestimate the stickiness of an app that’s native to the device.

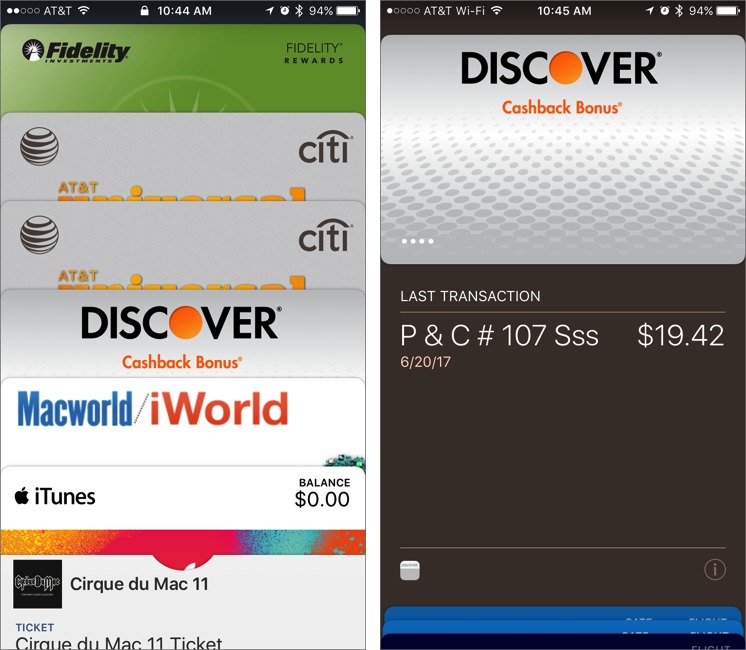

Credit Cards — If your credit card issuer is on board and you shop mostly at large chains, Apple Pay has the potential to let you leave credit cards at home. Plus, some stores let you pay via their own apps (like Walmart Pay — see “Walmart Pay Is Better Than You Might Expect,” 18 July 2016).

As a bonus, Apple Pay and similar apps can help you avoid paper receipts that fill your wallet, either storing them in the app or sending them to you via email.

Unfortunately, too many retailers still lack payment terminals that accept Apple Pay, so credit cards will have to stay in the wallet for now. But I have noticed that the silver paint on their raised numbers isn’t rubbing off quite so fast since credit cards come out of my wallet much less often.

As an aside, the rise of digital wallet technologies like Apple Pay also effectively killed off the nascent market for a single multi-account card — such as those offered by moribund or defunct companies like Coin, Plastc, and Swyp — that could be used in place of credit cards, debit cards, gift cards, and other loyalty cards.

Debit/ATM Cards — Apple Pay supports many debit and ATM cards just like credit cards. Using Apple Pay to pay with a debit card works mostly like paying via Apple Pay with a credit card, though you have to enter a PIN at the sales terminal.

Getting cash out of an ATM is a slightly different story. Many banks have updated their ATMs to include contactless card readers that will accept an ATM or debit card that has been added to the Wallet app.

The side benefit of using Apple Pay at an ATM is greater security because card skimmers — which thieves commonly use to capture ATM card data — can’t steal data from contactless card readers.

To use your debit/ATM card with an ATM, first double-press the Home button to invoke Apple Pay (this is best done with a finger that Touch ID doesn’t recognize). You can also open the Wallet app and tap your debit/ATM card. Then hold the iPhone near the contactless reader symbol and activate Touch ID by placing a recognized finger on the Home button. If you have one, you can also use your Apple Watch — double-press the watch’s side button to bring up Apple Pay. Finally, enter your PIN on the ATM’s keypad.

Alas, not every ATM has a contactless card reader. Even for those that do, some types of transactions, such as deposits, may still require a physical card. Until the ATMs close all these particular loops, my ATM card will have to remain in my wallet.

Transit Passes — If you live in the right place, such as New York City, London, or Japan, you can use Apple Pay to ride public transit (things have improved significantly since Steve McCabe wrote “Around The World With Apple Pay,” 13 May 2015). Apple Pay support for transit payments helps riders save time, particularly when

transferring from one service to another; can help speed passengers through fare gates; and could even save the transit authority some costs.

Sadly, far too few transit systems support Apple Pay yet. Even in Apple’s home territory of the San Francisco Bay Area, for example, commuters can use a single Clipper Card to navigate over 20 separate transit agencies but can’t use Apple Pay. It would be nice to replace that card with a virtual card in the Wallet app, but that hasn’t happened yet.

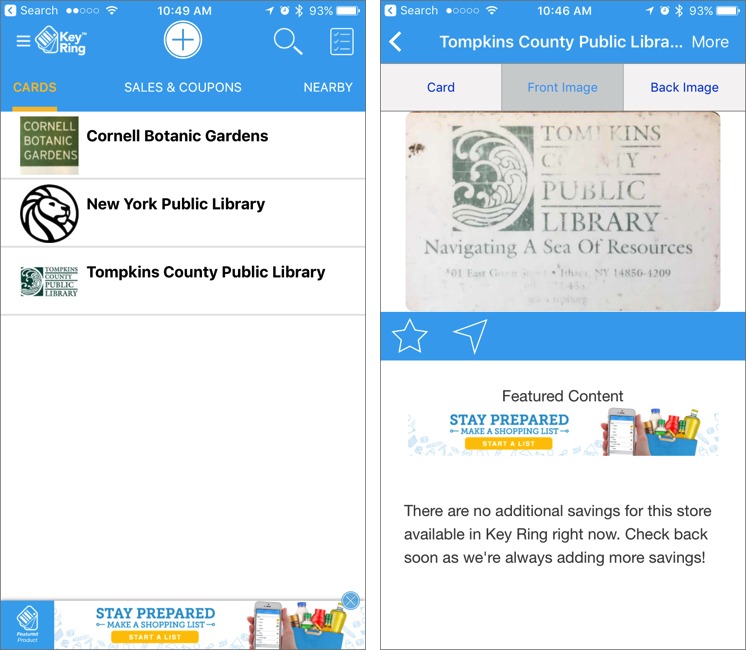

Loyalty/Stored Value/Gift/Membership Cards — Department stores, drug stores, and restaurants are starting to see the value of having their loyalty programs appear in their apps or in Apple’s Wallet. Some are placing special offer coupons right in the Wallet app, giving customers one less thing to forget when heading out for the day and increasing the odds of an impulse buy.

Apps like Stocard and Key Ring offer you the opportunity to put all your loyalty cards into one app and may also present information about ads and store sales. These apps may also be able to handle membership cards that have barcodes. For instance, TidBITS publisher Adam Engst was able to lighten his wallet load by adding his Tompkins County Public Library card and others to Key Ring.

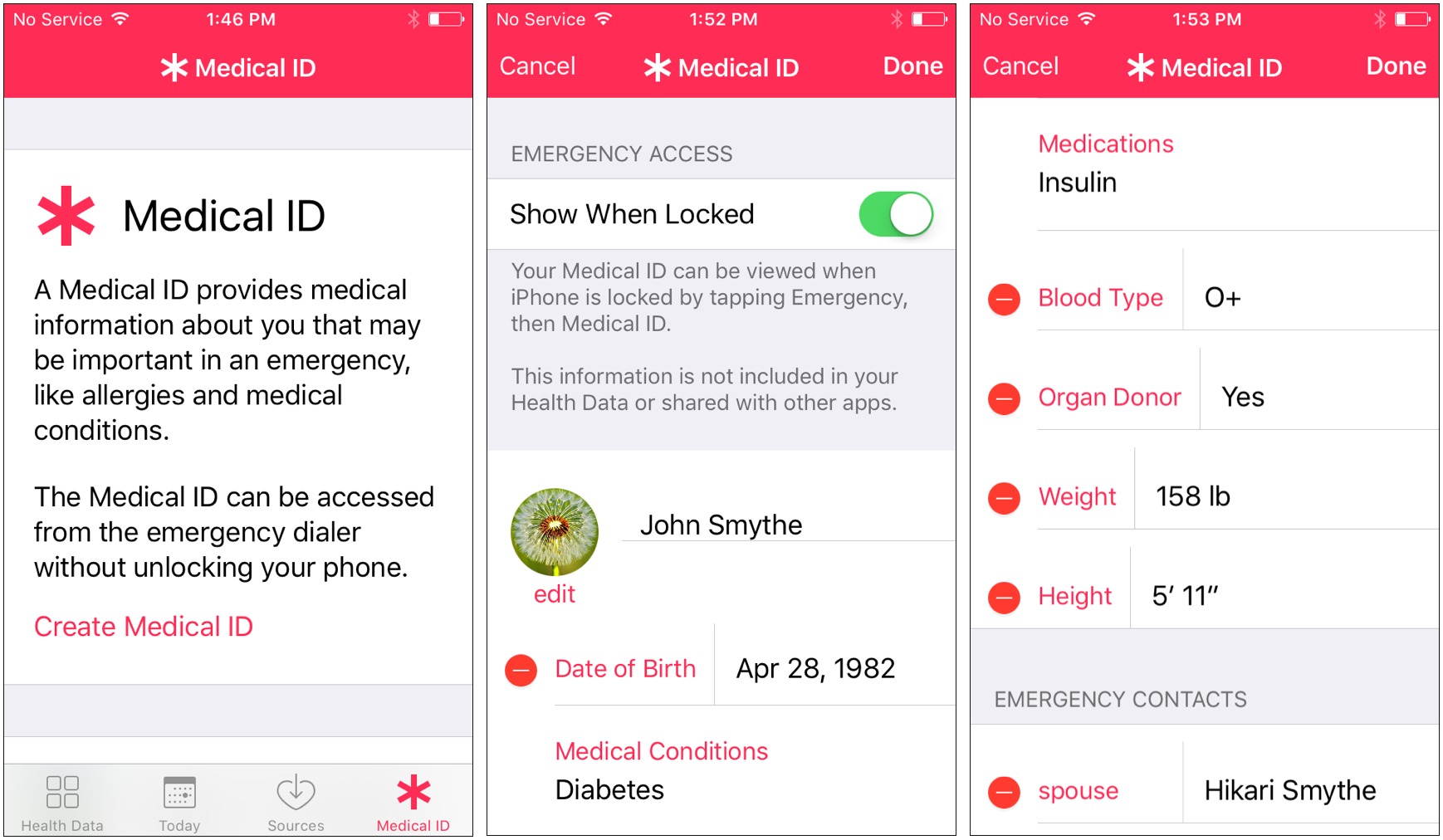

Health Insurance/Emergency ID — Everyone should carry this sort of information because you never know when a medical emergency (such as a bus) will strike. Ouch!

Fortunately, major health care providers offer apps that often include account details or even on-screen replicas of insurance membership cards. Search on your health insurance provider’s Web site to see if they provide such an app.

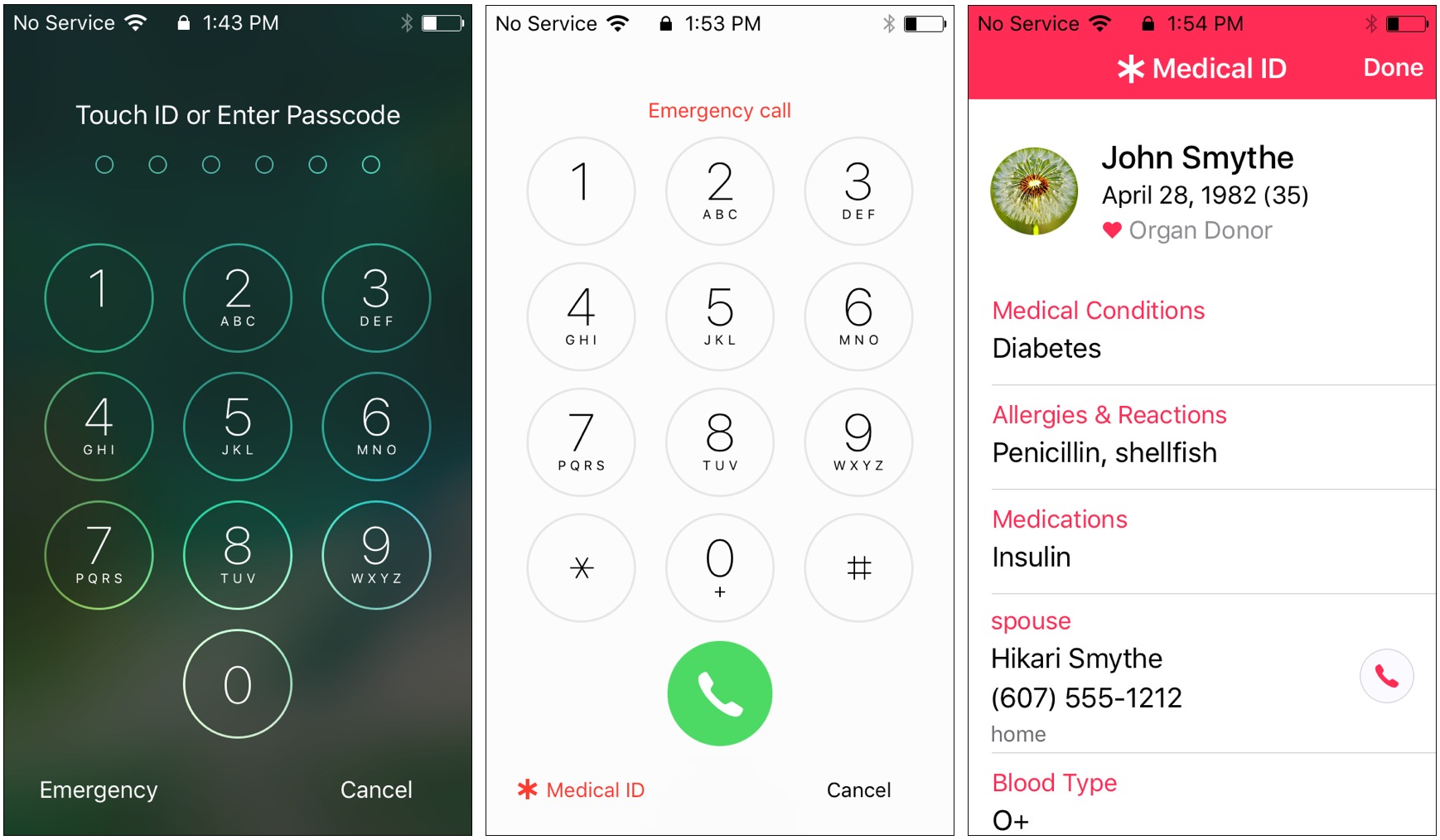

In addition, Apple’s Health app includes a Medical ID into which you can enter your age, blood type, height, weight, and organ donor status, along with people to contact in case of emergency.

If you’re in an accident, emergency responders can access this information from the iPhone’s Emergency screen (tap Emergency on the Passcode screen) or by pressing and holding the side button on the Apple Watch.

Be sure to tell your iPhone- and Apple Watch-using friends about the iPhone’s Medical ID, since it will be useful only if it contains helpful information and people know to access it.

Government ID — While you could take a picture of your driver’s license and store it on your iPhone, that’s not going to get you very far if you have to present your actual ID card to get into a bar, past the TSA at the airport, or to a police officer who has just pulled you over.

That said, Alabama now offers a digital driver’s license, and quite a few other U.S. states — and other countries — are exploring the possibility.

The idea of replacing passports and driver’s licenses is rife with security and privacy concerns, however. Digital IDs may initially be offered as a complement to traditional plastic or paper forms of identification.

For instance, the Mobile Passport app is authorized by U.S. Customs and Border Protection. It doesn’t replace the need for a passport; it merely permits U.S. and Canadian citizens to submit their passport control and customs declaration information via an iPhone or iPad (rather than fill out a paper form) and then bypass the regular line when entering the United States at selected airports and seaports.

We’re still far from solving these larger tensions surrounding identity, privacy, and security, so we’ll probably have to resign ourselves to carrying physical wallets for a bit longer.

Right now, if I could put all of these options to work, I might be able to downsize my current wallet to just a bit of cash, my driver’s license, a credit card, an ATM card, and a transit fare card.

That would be pretty much everything I need. Except for some hard candy, of course.

HEVC and HEIF Will Make Video and Photos More Efficient

If you haven’t already experienced abbreviation overload, Apple has added two more to your plate: HEVC (High Efficiency Video Coding) and HEIF (High Efficiency Image File Format — yes, it’s short one F). These two new formats will be used by iOS 11 and macOS 10.13 High Sierra when Apple releases them later this year.

While you may not have heard of HEVC or HEIF before, both are attempts to solve a set of problems related to video and still images. As people take photos and shoot video at increasingly higher resolutions and better quality, storage and bandwidth start to become limitations. Even in this day of ever-cheaper and ever-faster everything, consuming less storage space and requiring less bandwidth when syncing or streaming still has many benefits.

The Current Landscape — Those of us who have been around the block a few times have seen plenty of image formats come and go. Once, I thought the Kodak-backed FlashPix format might make inroads because of how it created a hierarchy of multiple sizes of images in a single file for faster retrieval. But it was not to be.

Since the 1990s, only the PNG (Portable Network Graphics) format, designed to avoid certain patents then extant, has joined the pantheon of widely supported, well-established image formats, alongside JPEG and GIF. (The long-established TIFF isn’t used on the Web, but it remains important in publishing workflows.)

The main split between image format types is whether they’re lossless or lossy. Lossless formats retain pixel-for-pixel details and tones exactly, at the expense of a larger file size. Compression in lossless formats reduces the storage required for redundant information without discarding detail. Lossy formats rely on algorithms to approximate detail and tones across regions of an image, allowing for typically much smaller file sizes.

None of the popular formats fit all needs. JPEG is lossy, so it’s great for photos but less useful for screenshots, and it doesn’t support an alpha channel for transparency, like GIF and PNG. GIF is lossless, but relies on limited color palettes, making it great for certain kinds of artwork, but poor at reproducing photos. (Reduced color palettes were more important when color displays had shallow color depth and bandwidth was more constrained). GIF also supports animation, unlike JPEG and PNG’s most common implementation. PNG, either lossy or lossless, works particularly well for screenshots and was designed around the patent encumbrances that once restricted GIF usage. PNG and JPEG are both used on about 74 percent of Web sites, but GIFs still appear on 36 percent of sites. PNG didn’t succeed in killing GIF, but it made huge inroads.

HEIF tries to combine all the best aspects of PNG, JPEG, and GIF, while dramatically improving compression and adding new features like the capability to store bursts of photographs.

Video formats have suffered from a more fraught path, because many were caught up in newer patents that hampered widespread adoption. Image formats had to deal with patents, too, but either they were near the end of their lives when the Web was young, as with LZW compression, or the makers of various tools to create and display images — from Photoshop to Internet Explorer — had already licensed all the necessary bits and pieces.

These video patents complicated things for Web sites. Questions arose as to whether sites would have to pay royalties for every view, free software groups debated the use of encumbered standards, and Flash took off as a cross-platform delivery package for video, because Adobe took care of all the back-end licensing and display issues.

Ultimately, the MP4 family of standards and its H.264 codec (encoder/decoder) won the day, with the vast majority of video available on the Web now using that format. (The group that pooled patents for H.264 said it wouldn’t collect royalties for free Internet-delivered video. Hardware-accelerated encoding and decoding followed. That took the wind out of competitors’ sails.)

What will be the real-world benefits of these new formats? Let’s start with HEVC and move on to HEIF.

HEVC: Encompassing the Future While Shrinking the Past — Video streaming gobbles up over 70 percent of evening Internet traffic, and network-management firm Sandvine estimates it’s on track to hit 80 percent in 3 years. Thus, streaming video companies, ISPs, and viewers who have monthly caps or overage fees have a huge incentive to get more from less, and HEVC is the solution. Apart from Google’s 4K-capable VP9 codec, HEVC is the only reasonable path for most streaming services to affordably and practically feed out 4K Ultra-High Definition (UHD)

video for mobile devices. (VP9 is built into Android starting with version 5.0 Lollipop.)

HEVC is another name for the H.265 standard, and it’s being promoted as taking 50 percent less data to produce streams or downloads of the same quality as H.264 when the resolution is 1080p or less. Netflix, which accounts for about half of the aforementioned primetime data usage in the United States, found that it did indeed achieve 50 percent savings. (Google’s VP9 hit the same 50 percent mark.) Netflix suggests 5 Mbps for HD video now, which would consume about 340 GB for 150 hours of content.

When it comes to 4K UHD video, HEVC uses about 40 percent less data. But that’s still tremendously more efficient. Netflix streams only 4K to televisions released starting in 2014 that had an earlier version of the HEVC hardware decoder. The streaming company currently advises a constant 25 Mbps or higher rate to stream its 4K content, which is about 1.7 TB for 150 hours of viewing. It would be over 40 Mbps at H.264 compression rates.

How can HEVC achieve such a notable improvement in compression without sacrificing quality? As with the jump from MPEG2 to H.264, it involves hardware acceleration on the encoding side. With chips that can perform specialized calculations, algorithms that perform more intensive analysis of video to find places to compress become more viable. HEVC can require up to 10 times more computation than H.264 to encode at the same bit rate!

But this is asymmetrical. In plain English, HEVC works because it’s relatively cheap to buy super-powerful computers with specialized chips to encode the video in production, but even tiny mobile devices can decode those highly compressed streams or downloads quickly and easily. Producers crunch the files; viewers reap the bandwidth benefit.

Both H.264 and HEVC break down every frame in a video into a series of rectangles (mostly squares) based on the image’s tonal values, with the goal of grouping similar tones for more compression. A frame that has a large area of blue sky and small figures walking across a desert could obviously be compressed better if the blue sky and desert regions were broken out from the people walking across it. HEVC can encode larger areas at once, which results in higher compression for less-differentiated detail.

HEVC is also much better at “predicting” how elements in a frame will change from frame to frame and in which direction those elements will move. The full explanation is eye-glazing, but the summary is that increased compression efficiency both within a frame and between frames lets HEVC gain that extra 40 to 50 percent reduction.

Smaller files and fewer bits-per-second required for streaming are great when you’re Netflix, but why should you care as an individual user or even a company using video from iPhones as part of your workflow? Because every bit saved is a bit you don’t transmit and a bit you don’t store.

For starters, if a video occupies only half the space for the same quality, your iPhone’s precious storage goes twice as far before you have to sync or offload video.

At the average user level, if you’re an iCloud storage subscriber above the free 5 GB tier, when you cross 200 GB with your current media needs, you suddenly leap from $2.99 a month for 200 GB to $9.99 a month for 2 TB. Halve your storage and you save that difference in cost. For even relatively modest video production houses storing massive amounts of video, the same scenario applies to local SSD or RAID storage and remote cloud storage, and could result in savings of tens of thousands of dollars per year.

Similarly, if you send or receive video via cellular data, you might be able to drop to a cheaper data plan without being throttled or charged for overages. And for commercial users, being able to transfer less data to cloud storage or stream at lower bit rates could reduce costs significantly. Amazon S3 and Google Cloud may offer cheap storage and transfer, but it still adds up. Half of anything is half as much!

As viewers, we should get better and more consistent quality television and movie streaming on our iOS devices and Macs, as well as on the fourth-generation Apple TV, which is slated to receive HEVC decoding in tvOS 11 (see “What’s Coming in tvOS 11,” 15 June 2017). People with lower broadband throughput rates will potentially use the same amount of data and see a much crisper picture. Those with higher bandwidth connections will consume half as much data for the same results.

The central question about HEVC is how easy or hard it will be to capture, edit, and play back on various devices. Apple hasn’t named compatible devices, but in a developer presentation, it provided a clear rundown of the hardware and software support (go to 22:00 in the video to listen and see).

In short, all Macs and iOS devices that run the upcoming releases will be able to decode HEVC at least in software. But for hardware decoding, you’ll need an iOS device with an A9 or later and a Mac with an Intel Skylake or Kaby Lake processor (6th and 7th generation Intel Core). On the iOS side, that means an iPhone SE, iPhone 6s or later, any iPad Pro, and the fifth-generation iPad. The 2016 MacBook Pro models have Skylake processors, and the 2017 iMac and MacBook Pros sport Kaby Lake chips.

Depending on the size of files and other parameters, HEVC software decoding might be erratic or consume much more battery life than H.264. Smart Web sites may check a device’s vintage and iOS apps can use new developer queries about supported video formats, and then feed out H.264 if HEVC might suffer from software decoding hiccups. Of course, that means older hardware that’s technically capable of HEVC might not get the full bandwidth advantage, but owners will probably then appreciate H.264’s battery savings, reduced fan noise, and smoother video.

If you want to edit and encode with HEVC, you’ll have the same issues as decoding, and it probably won’t be practical without a newer Mac.

(A technical aside for those who care about deep color. Both H.264 and HEVC allow for 10-bit color, which provides richer differentiation of tones than 8-bit color: a billion different shades instead of just over 16 million. 4K and 5K iMacs and the Mac Pro support 10-bit color, as do the 2016 and later MacBook Pros, and external monitors on some other 2015 and later Macs. 2016 MacBook Pros with Skylake chips include only 8-bit HEVC hardware encoding; Kaby Lake models handle 10-bit.)

Because not every device will display HEVC video, exporting will produce compatible formats for social media and other sharing, as you can do with Photos, iMovie, and other apps today.

With video out of the way, HEIF will seem vastly simpler by comparison.

A Container for Images, Rather Than a Simple File Format — Even though it’s billed as an image format, HEIF is in fact a container that rethinks what an image format needs to do in today’s complex world. An HEIF file will be able to hold text, audio, video, still images, and sequences of frames for bursts and animations, and software will be able to extract and present the relevant information depending on what we’re trying to do.

HEIF is built on an ISO standard — hurray! — developed into a full spec by the Moving Picture Experts Group (MPEG). Apple has based its implementation on a second, more fully realized version that the company said at WWDC will soon be released. Also, Apple says HEIF is pronounced “heef,” rhyming with “beef.” (An Apple developer presentation offers a good amount of detail, if you want the not-too-gory bits.)

Once again, compression is perhaps HEIF’s most significant benefit. To make things simpler, HEIF can use HEVC compression. That’s both because HEVC compression is more efficient than JPEG, but also because Apple can use HEIF to store bursts of images and animations (think Live Photos), both of which benefit from HEVC’s inter-frame compression.

Less obvious benefits include better support for alpha channels, which are used for transparency and masking of images, and for deeper color, something Apple has been pushing into its hardware for a few years. HEIF can also break an image into rectangular regions so editing and display software quickly retrieve just the necessary adjacent pieces without loading the entire file. And it can store both an original image and images derived from the original, much like apps like Lightroom store a base image and then record a series of transformations.

Although HEIF can be used to store bracketed images — photos of the same scene taken in quick succession with different exposures — to let software produce high dynamic range (HDR) output, Apple instead generates HDR images directly in the image signal processor in iOS devices. Third-party software could opt to bypass Apple’s hardware and use HEIF for this purposes. ProCamera, for instance, has its own HDR mode.

But with two-camera iPhones, currently including just the iPhone 7 Plus, Apple will store the depth map that it derives for its Portrait-mode photographs in the HEIF file. The depth map identifies a series of planes at a range of distances from the foreground. This lets Apple separate out figures in the front and aesthetically blur the background to achieve the “bokeh” effect (see “Behind the iPhone 7 Plus’s Portrait Mode,” 24 September 2016). But it can also be used for a host of interesting effects by developers, who will be able to access the depth map in iOS 11 both as the camera is in operation and from stored HEIF images. Apple showed examples like a foreground figure being

in full color, while the background was in black and white. It will also make it easy to composite foreground elements against artificial backdrops.

I won’t reiterate the advantages for storage, since they apply just as much to photos as to video. As someone with dozens of gigabytes of video and hundreds of gigabytes of photos, I’ll likely find more savings from HEIF than HEVC video.

Just like HEVC, HEIF relies on newer hardware for hardware decoding: iOS devices need an A9 or later processor, and for Macs, the same Skylake and Kaby Lake models noted above. All other iOS devices and Macs that can run iOS 11 and High Sierra rely on software decoding.

Because HEIF is a container format, it gives individual implementors like Apple a lot of flexibility about what ends up inside. I hope that doesn’t create compatibility issues when moving HEIF files between other platforms that eventually support it as a native file type. At the moment, HEIF files can be read only by Apple beta software. Conceivably, we’ll see Adobe Photoshop and other software gain support.

Web browsers won’t support HEIF initially, and it’s not inherently suited for the Web because any given HEIF file could include all sorts of excess data. I expect that Apple and others will define kinds of HEIF that will be appropriate for Web usage, such as a substitute for animated GIFs and for better compression than JPEG provides. Web servers can already supply different kinds of image and video types based on browser versions, so HEIF would just extend that capability. But Apple hasn’t said anything along those lines yet.

Apple has created developer tools that let apps assess what format an image has to be in to share or display, and export and serve that up as needed. iOS, macOS, Apple’s apps, and independent apps will perform a lot of conversions or offer export options, while retaining and passing HEIF for intra-ecosystem use.

Are HEVC and HEIF Like USB-C for Media? — People still have issues with the USB-C connector used for USB 3.1 and Thunderbolt 3 because it requires adapters, raises compatibility issues among identical connectors, and generates anxiety about what will work with what. (I’m a big fan of USB-C — as evidenced by my owning a 12-inch MacBook and a 2017 iMac — but I understand the complaints.)

HEVC and HEIF shouldn’t suffer from the kind of confusion that plagues USB-C, however, because Apple has built its support around the notion that only devices within Apple’s ecosystem will support the formats natively. Moving outside Apple’s ecosystem will typically — at least initially — require transcoding and export, and those conversions will almost certainly happen without you even realizing. Apple is encouraging developers to keep this approach in mind, too.

The one sore spot you might hit is if you don’t upgrade all your devices to iOS 11 and High Sierra at the same time, or if you own older hardware that can’t be upgraded. For instance, if you use the same iCloud account with iCloud Photo Library across both new and old devices, I’m not clear on how pre-HEIF/HEVC platforms will deal with those images. Apple hasn’t provided guidance about that yet.

Another question that Apple has yet to answer is how your existing JPEG photos and H.264 video will be treated when you update to High Sierra. Will Photos automatically convert your entire library? What about files outside of Photos?

Nevertheless, the advantages for HEVC and HEIF are clear, and the transition shouldn’t be rocky if you move forward all at once. But hey, keep good backups, just in case.

TidBITS Watchlist: Notable Software Updates for 3 July 2017

Transmit 4.4.13 — Panic has released Transmit 4.4.13 to remove support for a now-deprecated Dropbox API for syncing favorites. Panic promises to introduce its own synchronization service, called Panic Sync, in the forthcoming Transmit 5. Other changes in Transmit 4.4.13 include improved behavior when adding new custom Amazon S3 Upload Headers and strengthened security during the auto-update process. ($34 new from Panic and the Mac App Store, free update, 30.2 MB, release notes, 10.9+)

Read/post comments about Transmit 4.4.13.

Moneydance 2017.3 — The Infinite Kind has released Moneydance 2017.3 with improved computer-to-computer syncing and smoother setup of synced computers. The personal finance manager gains a new text file importer that can handle CSV, tab-delimited, and other formats with automatic delimiter, field type, and date format detection, as well as duplicate detection and elimination, automatic category guessing, and description cleanups. The update also improves automatic merging of downloaded transactions, moves to the Dropbox v2 API, enhances security by removing all traces of previous encryption passphrases, fixes a bug that

displayed dividend reinvestments as regular dividends, improves scripting with Python, and updates the trusted certificate list to enable connections to more banks. ($49.99 new from The Infinite Kind with a 40 percent discount for TidBITS members, free update, $24.99 upgrade from versions previous to Moneydance 2015, 96.8 MB, release notes, 10.7+)

Read/post comments about Moneydance 2017.3.

MoneyWiz 2.6 — SilverWiz has released version 2.6 of MoneyWiz with added investment account functionality that supports over 3700 institutions. MoneyWiz automatically refreshes the values of your holdings once per hour; supports stocks, bonds, options, ETFs, precious metals, and other commodities; and can handle all types of investment/brokerage accounts, including retirement accounts (IRA, 401k), self-managed accounts, and more. Because support for investment accounts requires a new database structure, you’ll need to update MoneyWiz for iOS to version 2.6 so that ; continues to work.

The personal finance manager also now marks newly downloaded transactions with “new” in the transaction status flag, fixes a bug related to an incorrect calculation of carried balance when creating a budget, resolves a scaling issue related to fullscreen mode on an iMac with 4K Retina display, and addresses a bug that caused the app to freeze on quit when automatic backup was enabled. ($59.99 annual subscription, free update, 26.3 MB, release notes, 10.8+)

Read/post comments about MoneyWiz 2.6.

ExtraBITS for 3 July 2017

In ExtraBITS this week, we continue our celebration of the iPhone’s 10th birthday: Joanna Stern lives with the original iPhone for a day and some of the iPhone’s creators worry about its impact on society.

Trying to Live with the Original iPhone in 2017 — The Wall Street Journal’s Joanna Stern vowed to live with an original iPhone for a week, but she lasted only 12 hours, as summarized in this amusing video. The original iPhone lacks a front-facing camera, video capture, and Siri, and both performance and battery life were underwhelming. Worst of all, most apps and Web sites don’t work with it anymore. There was a headphone jack, but even then you needed a dongle to use non-Apple headphones. It’s easy to say that technology has advanced considerably since 2007,

but it’s also clear that many problems stemmed from a lack of emphasis on backward compatibility. Be sure to watch until the end to see Stern’s helmet cam setup! The article is limited to subscribers, but the video is free for everyone.

10 Years Later, iPhone Creators Worry about Smartphone Addiction — During a panel at design firm IDEO, three former Apple employees gathered to discuss the iPhone’s impact after 10 years. All agreed that they’re concerned by society’s addiction to smartphones. “I don’t feel good about the distraction. It’s certainly an unintended consequence,” said Greg Christie, who led Apple’s human interface team. Bas Ording, who designed much of the iPhone’s multi-touch interface, said, “The positive is that it’s easy to use, so a lot of people can

use it. The downside is too many people are staring at their phones. I probably do it, too.” And input engineer Brian Huppi, who helped develop the iPhone’s touchscreen, worried about how smartphone use is implicated in automobile accidents, saying “I’ve got to believe there’s just so many accidents on the road now from people looking at their phones.” However, there was also consensus that the iPhone has been as significant of a change as radio, television, and the Internet were, and that we’ll eventually adapt to it.