Developers v. Apple: Outlining Complaints about the App Store

The early days of the App Store might have been rocky, but from the outside, they seemed like a virtual gold rush. The media was full of stories of independent developers becoming wealthy from simple apps. But after that initial excitement, many smaller developers now find themselves having a hard time making even a modest living in the App Store and feel like they’re locked in an abusive relationship with Apple.

Simultaneously, government regulators and media alike have started to focus more attention on the business practices of Apple and other big tech companies. Apple is already facing new regulations in the European Union and increased scrutiny at home (see “A Quick Rundown of Big Tech’s Showdown with Congress,” 31 July 2020). Depending on what happens in November’s US elections, that scrutiny could intensify.

At this critical juncture for the company, we wanted to take the opportunity to analyze the complaints against Apple regarding how it runs the App Store. We’ve spent a long time observing and considering these issues, and you may agree or disagree with our evaluation and conclusions. As we are neither regulators nor Apple executives, the decisions are ultimately not up to us. We merely want to lay out the issues and offer suggestions on how Apple can improve, for the sake of users, developers, and even the long-term viability of the company itself.

That 30% Cut

Let’s start with the most surface-level complaint: ever since Apple unveiled the App Store in 2008, the company has taken a 30% cut of every app sold and every in-app purchase. Apple later reworked this structure slightly so that the company takes a 30% cut of a recurring subscription only in the first year, after which it falls to 15%.

When he introduced the App Store, Steve Jobs said that the 30% cut was purely so Apple could break even. While there’s no requirement that the company honor that initial claim, it’s hard for small developers to see Apple raking in billions in profit while they struggle to earn a living.

Representative David Cicilline (D-RI), who recently chaired Congress’s hearing with CEOs of four Big Tech companies, including Tim Cook, said on a recent appearance on The Vergecast:

Because of the market power that Apple has, it is charging exorbitant rents—highway robbery, basically—bullying people to pay 30 percent or denying access to their market,” said Rep. Cicilline. “It’s crushing small developers who simply can’t survive with those kinds of payments. If there were real competition in this marketplace, this wouldn’t happen.

Now, to be sure, there are much broader issues with the App Store than the so-called “Apple tax,” but even discounting Cicilline’s overheated language, we can’t ignore the issue, either. Many of the other App Store squabbles over the years have revolved around that cut, who has to pay it, and how developers can work around it. For instance, it was the core of Spotify’s recent kerfuffle with Apple:

Apple requires that certain apps pay a 30% fee for use of their in-app purchase system (IAP). However, the reality is that the rules are not applied evenly across the board. Does Uber pay it? No. Deliveroo? No. Does Apple Music pay it? No. Apple does not compete with Uber and Deliveroo. But in music streaming Apple gives the advantage to its own services.

But there are problems with Spotify’s examples. One rule that Apple applies consistently is that real-world goods and services aren’t subject to the 30% cut. That’s why Uber doesn’t pay the fee, and why you can purchase physical goods through the Amazon app, but you have to open a Web browser to buy Kindle ebooks. And of course, Apple Music doesn’t pay the 30% cut because Apple would be paying itself. That’s just silly.

But it’s a real financial cost to developers. The Omni Group recently had to lay off many of its employees, and Brent Simmons, who was among those laid off, had this to say about the situation:

To put it in concrete terms: the difference between 30% and something reasonable like 10% would probably have meant some of my friends would still have their jobs at Omni, and Omni would have more resources to devote to making, testing, and supporting their apps.

While we can’t discount expert testimony—Simmons said the 30% cut hurt Omni, and we believe him—it should be pointed out that many developers have thrived in the App Store. Plus, everyone knows about the 30% going in and should be working it into their business planning. Would more developers succeed with a lower cut? We honestly don’t know.

Apple has responded the most vigorously to this issue of the 30% cut. Apple’s arguments break down to the following:

- The App Store has generated a tremendous number of jobs and billions of dollars in payments to developers.

- Apple’s cut is much lower than if the software was sold through retail outlets or cellular carriers, which charged fees as high as 70%.

- Most apps are free and thus generate no revenue for Apple.

Apple has made these arguments consistently, and they were clearly outlined in Tim Cook’s opening statement to Congress.

However, it is misleading for Apple to compare the App Store to physical distribution. It’s not as if the only places to buy software before the App Store were brick-and-mortar stores. Internet-distributed commercial software started in the 1990s and was commonplace in the 2000s. Kagi was founded in 1994, and eSellerate in 2000, both with the express purpose of enabling developers to sell their software over the Internet. Mac users especially know this because it wasn’t as though you could walk into a CompUSA and buy a copy of BBEdit.

Developers have been distributing software online for a long time, with rates much, much lower than 30%—more like 3% to 8%. And they still do! Developers on the Mac and other platforms still often distribute outside of the App Store at much lower rates. In fact, the Mac App Store seemed to stagnate for years until Apple found ways to lure back high-profile developers like BBEdit’s Bare Bones Software.

The 30% fight may soon be coming to a head. Epic Games, producer of Fortnite, arguably the hottest game in the world, pulled a fast one by slipping in an option to buy in-game currency at a discount, bypassing Apple’s standard in-app payment system. Epic is playing a game of chicken with Apple and is so far losing. Apple quickly booted Fortnite from the App Store, though said in a statement that they were willing to let it back in as long as Epic follows the rules. Epic is now suing Apple in an effort to lift App Store rules:

Epic seeks injunctive relief in court to end Apple’s unreasonable and unlawful practices. Apple’s conduct has caused and continues to cause Epic financial harm, but as noted above, Epic is not bringing this case to recover these damages; Epic is not seeking any monetary damages. Instead, Epic seeks to end Apple’s dominance over key technology markets, open up the space for progress and ingenuity, and ensure that Apple mobile devices are open to the same competition as Apple’s personal computers. As such, Epic respectfully requests this Court to enjoin Apple from continuing to impose its anti-competitive restrictions on the iOS ecosystem and ensure 2020 is not like “1984”.

The clever reference to Apple’s “1984” ad aside, it’s hard to sympathize with Epic here. What it did was both sneaky and a blatant violation of the App Store rules, and Apple is reportedly now terminating Epic’s developer account. Epic is also suing Google.

Epic isn’t some small, struggling developer—Fortnite is one of the top-grossing apps on iOS, making $455 million in 2018 alone. And that’s just the App Store! Fortnite is also available for Windows, Mac, Android, and every mainstream gaming console. Apple’s 30% cut certainly isn’t breaking Epic’s business. The entire situation seems to be an effort to influence regulators.

Apple Picks Winners and Losers

At the Congressional hearing, Representative Val Demings (D-FL) expressed concern over Apple disadvantaging third-party apps in order to promote its own. Demings said:

I am concerned that Apple’s policies are also picking winners and losers in the app economy, and that Apple rules mean Apple apps always win.

The specific example Demings cited was Apple’s sudden banning of parental control apps using mobile device management (MDM), with the insinuation that Apple banned those apps to boost its own Screen Time feature, which was introduced in iOS 12. Cook defended the decision, as the company did at the time, by saying that apps that abused MDM in such a way were a threat to children’s privacy.

And that was true! But here’s the weird thing: Apple reversed course weeks later, specifically allowing parental control apps to use MDM. What happened to those privacy concerns? Even stranger, parental advocates had suggested opening API access to Screen Time, which would have been a “cleaner” solution.

There’s also a problem with Demings’s timeline: iOS 12 came out in September 2018, and Apple banned those apps in April 2019, about seven months later. That seems late if the goal was to boost Screen Time. Also, why would Apple feel the need to ban existing apps in order to boost a feature from which it makes no revenue?

Demings could have chosen better examples. Apple has prevented apps from coming to the App Store only to implement them in iOS later. An infamous example is f.lux, an app for adjusting blue light levels throughout the day. The developers had been petitioning Apple to allow it in the iOS App Store since 2009 but were told it was “too weird.” Of course, a similar feature later appeared in iOS in the form of Night Shift.

Moreover, Apple literally does choose winners and losers. An obvious example is the annual Apple Design Awards, which undoubtedly boost sales and downloads of the apps that Apple anoints. Even beyond those awards, Apple picks winners in the App Store every day with its featured apps, which benefit from top billing on the Today page of the App Store app.

To be fair, I’ve heard from developers that these featured articles don’t provide as big of a boost as one might think—people mostly interact with the App Store by searching, not browsing. But that doesn’t help Apple’s case. Either it admits that yes, it picks winners, or it has to acknowledge that it tries to promote certain apps, but it doesn’t help much. Neither is a good look.

Regardless of how well App Store features work, consider it from the point of view of a regulator. The App Store is the only place a developer is allowed to sell apps to iPhone and iPad users. Why are some apps highlighted? Why does Apple get complete control over distribution, take a cut of everything developers make through the App Store, and then arbitrarily decide which apps to put on the first screen? How is that a level playing field?

App Store Ads

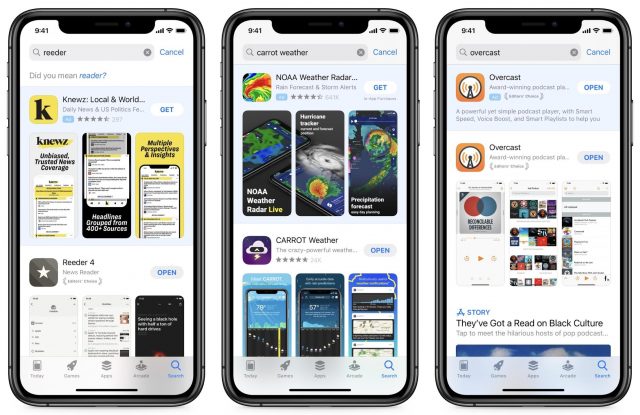

The App Store’s field can get even more tilted toward those who are willing to pay to play. Not only does Apple choose to highlight some apps, but thanks to App Store search ads, developers can pay to have their apps featured above those of their competitors. Numerous developers have complained publicly about this practice, saying that to even be competitive, they have to pay more money to Apple, on top of the 30% cut.

I searched the App Store for a few of my favorite independent apps by name. When I searched for the RSS app Reeder, the top hit, a paid ad, was an app called Knewz. I searched for CARROT Weather, and the top hit was an ad for NOAA Weather Radar. A search for Overcast… well actually, that pulled up an ad for Overcast because the developer, Marco Arment, paid for the placement. I guess I’m picking winners here too, but I don’t run the App Store.

At least Apple tastes its own medicine. A search for “Podcasts” placed an ad for iHeart over Apple’s own Podcasts app.

The upside of App Store search ads is that a smaller developer can—if they have the money—buy ads against a larger developer and potentially level the playing field. Of course, that assumes the larger developer won’t just outbid the smaller developer.

Nonetheless, it seems troubling for developers to have to pay Apple an additional fee to get top billing, even when users are searching for their apps by name. And as a user, it’s annoying that the specific app I search for is not the top result.

This is aside from other issues with App Store search, such as how easily it can be gamed and how it’s cluttered with junk and counterfeit apps. Let’s look at that last one.

Counterfeit Apps

One selling point for the App Store, and for Apple’s complete dominion over the distribution of iPhone software, is that Apple reviews each app to maintain a high standard of quality. This isn’t entirely untrue. Malware isn’t much of a concern for iOS users. However, there is plenty of junk in the App Store, and developers have, at times, been stunned to discover that Apple has approved blatant rip-offs of their original apps.

I’m not just talking about apps simply being copied by competitors, which, as Marco Arment explains, can’t really be prevented. But rather, bogus apps that are potentially harmful. Developer David Barnard explored this a couple of years ago (see “David Barnard Explains How to Game the App Store,” 30 November 2018), explaining how unscrupulous developers build junk apps from readily available templates, toss in absurd subscriptions, and gather personal information for profit.

To be fair, this problem also plagues the Google Play Store, and Apple does ban some of these apps, but the problem still exists. A quick search reveals multiple how-to guides on how to avoid fake apps:

- MakeUseOf: 7 Tips for Avoiding Fake Apps on Mobile App Stores

- Trend Micro: Gambling Apps Sneak into Top 100: How Hundreds of Fake Apps Spread on iOS App Store and Google Play

- Lifehacker: How to Spot Fake Apps in Apple’s App Store and Google Play

Apple’s entire argument for a closed App Store and all the headaches and fees that it entails is that it provides a safe, curated experience where users don’t have to worry about junk. As it stands, Apple isn’t holding up its end of the bargain, which hurts both users and developers.

Some Developers Are More Equal Than Others

Tim Cook told a whopper during the Congressional hearing: “We treat every developer the same.”

Several counterexamples came up at the hearing. For example, Apple maintained a special team just to handle app approvals for the Chinese search engine Baidu. If that’s not being more equal, I don’t know what is.

Also, you can rent and buy movies from the Amazon Prime Video app, thanks to a special arrangement between Apple and Amazon (see “You Can Now Make Purchases in the Amazon Prime Video iOS and Apple TV Apps,” 3 April 2020).

Apple says this program, which “lets premium subscription video entertainment providers offer a variety of customer benefits,” is open to everyone. Still, Amazon Prime Video is probably the only app you’ve ever heard of in this program. It also lets these providers sidestep Apple’s 30% cut. And it was largely unknown until the shocking change to Amazon Prime Video.

Phil Schiller, Apple’s outgoing head of marketing, said in an interview with Reuters:

One of the things we came up with is, we’re going to treat all apps in the App Store the same—one set of rules for everybody, no special deals, no special terms, no special code, everything applies to all developers the same. That was not the case in PC software. Nobody thought like that. It was a complete flip around of how the whole system was going to work.

Alas, it seems that there are special deals and special terms. There is special code: private APIs that Apple reserves for its own use. And, unless you strictly look at brick-and-mortar retail, the bit about PC software isn’t true. The Windows world was, and still largely is, a completely open market, for both better and worse.

Capricious and Arbitrary Judgements

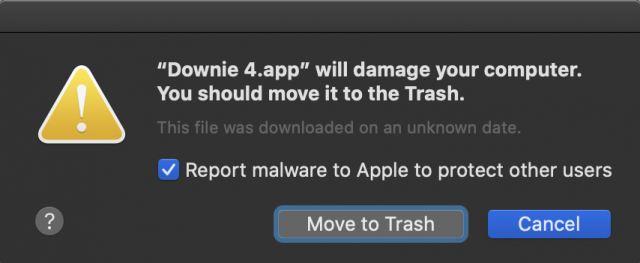

It’s common knowledge that Apple will yank an app from the App Store with little notice or warning. But apps don’t even have to be in the App Store now to get pulled by Apple. The most recent and egregious example of Apple’s overreach happened to Charlie Monroe Software, a small, family-based developer in the Czech Republic that develops a number of Mac apps, including Downie (see “Downloading YouTube Videos in macOS,” 18 July 2019) and Permute. (Disclaimer: Charlie Monroe’s apps are available on Setapp, which has sponsored TidBITS in the past.)

On 4 August 2020, Charlie Monroe Software found that it had been unceremoniously booted from the Apple Developer Program, its certificates had been revoked, and its apps no longer worked on most Macs. In fact, if users tried to launch one of the company’s apps, they were instructed that it was dangerous and that they should move it to the Trash.

In its blog post, the company wrote:

At this point you no longer know whether you have a business or not. Should I quickly go and apply for a job? Or should I try to found another company and distribute the apps under it? What should I do?

The good news is that Apple soon restored the account and apologized for the mistake. We don’t know if Apple compensated Charlie Monroe Software for the loss of business and damage to the company’s reputation. It’s disturbing that Charlie Monroe’s deplatforming appears to have been the work of an out-of-control automated system. At the very least, Apple should have conducted a human review before threatening a developer’s livelihood, and even if the human review identified abuses, Apple should have allowed the developer an appeal before revoking their certificates. You know, that whole “innocent until proven guilty” thing that’s considered an international human right by the United Nations.

Another recent and well-publicized example came from Basecamp’s Hey, which is a paid, proprietary email service. Apple initially allowed the Hey app in the App Store, but then rejected any updates until Basecamp agreed to allow signups through Apple’s payment system, thus giving Apple a cut. The two parties eventually reached an agreement, and Hey is now available on the App Store.

But for a short while, that didn’t seem likely. Apple’s former marketing head Phil Schiller went on the attack, saying, “You download the app and it doesn’t work, that’s not what we want on the store.” Initially, since you couldn’t sign up for Hey from within the app, due to Basecamp trying to avoid Apple’s 30% cut, yes, it was nothing more than a login screen if you didn’t already have an account.

However, many apps in the App Store function this way. Two notable examples are the Netflix app and Amazon’s Kindle app. In fact, Netflix briefly allowed in-app subscriptions before abandoning them. Even more baffling, Dropbox, which is a business productivity app with interactive elements, somehow slides into this category too, even though it’s not providing access to commercial media.

To explain this exception, Apple claims that apps like Netflix and Kindle are “reader apps.” Since they’re only for media consumption, it’s perfectly fine for them to be, as Schiller would say, an app that “doesn’t work.” The distinction is nonsense. Even Daring Fireball’s John Gruber, often somewhat unfairly accused of being an Apple fanboy, called it out as nonsense, summing up his arguments with a picture of Steve Jobs flipping off the IBM logo. Perhaps “reader app” means an app Apple would normally reject from the App Store but wants to approve without making some sort of general exception.

I could list dozens of examples of apps being unceremoniously yanked from the App Store, sometimes for reasons we can all agree upon, such as being actively malicious. In these cases, it’s good for Apple to have a kill switch to protect users. But in others, it’s harder to defend Apple’s actions.

Representative Jamie Raskin (D-MD) asked Cook about this absolute control Apple wields between developers and users. Cook was blunt and unapologetic:

Whether you look at it from a customer point of view or a developer point of view, there are enormous choices out there. If you’re a developer, you can write for Android, you can write for Windows, you can write for Xbox or PlayStation. If you’re a customer and you don’t like the setup, the curated experience of the App Store, you can buy a Samsung.

In other words, “If you don’t like it, leave.” However, I think this argument is disingenuous:

- It’s easy to say that it’s simple for an iOS user to switch to Android, but sticky Apple services make it much harder in reality. iMessage is notoriously difficult to switch away from, and Apple knows that. Switching is especially difficult for those who rely on a Mac or other Apple hardware and just aren’t enamored of being forced to purchase iOS apps through the App Store.

- Many iOS developers already also develop for Android. Whether or not they prefer one platform over another is irrelevant if they need both to make their business work.

That’s not to say that Apple necessarily owes users or developers anything, but again, we’re pointing out that, if nothing changes, the choice maybe not be left up to Apple for much longer. In theory, I’m all for “if you don’t like it, leave,” but the reality isn’t that simple for most folks, and regulators will take that into consideration.

Thankfully, Apple is addressing this problem, at least somewhat. After the Hey imbroglio, Apple announced two long-overdue changes to App Store policy:

First, developers will not only be able to appeal decisions about whether an app violates a given guideline of the App Store Review Guidelines, but will also have a mechanism to challenge the guideline itself. Second, for apps that are already on the App Store, bug fixes will no longer be delayed over guideline violations except for those related to legal issues. Developers will instead be able to address the issue in their next submission.

These are excellent policies that should have been in place from the start. The European Union has taken this even further with new regulations that prevent publishers like Apple from banning apps without notice. As developer Steve Troughton-Smith pointed out, Apple must give 30 days’ notice before removing an app, must disclose any preferential treatment, and must have an external mediator for issues that cannot be resolved by App Store review.

How these policy and regulatory changes will actually work out in the real world remains to be seen.

Banning Game Streaming Services

Amazingly, while Apple has made some progress, in other ways, the company has doubled down. After its Congressional hearing, Apple expressly forbade services like Microsoft’s Project xCloud and Google’s Stadia game streaming services. Before I explain what xCloud is and why Apple’s stated reasoning doesn’t hold water, I need to explain how these services work.

Modern video games need a tremendous amount of processing power, either requiring expensive desktop computers or specialized gaming hardware. Years ago, a company called OnLive came up with a crazy idea: what if you ran the games on a server farm and streamed the video output to the player? And then took input from the controller and sent it back to the server? It would be a “thin client” for video games. Such a system would require an extremely fast Internet connection, but in theory, it would enable you to play even the most demanding games on modest hardware.

While OnLive was a commercial failure, the system worked better than anyone expected. Since then, successors to OnLive have come from Sony, Microsoft, Google, and Nvidia, all of which have improved upon the concept.

It’s important to understand that with services like these, native game code is not running on your device. The game is running on a remote server, and you are interacting with the instance of that game running on that server. I point this out because any accusations of malware slipping through such a system are completely unfounded. The only way that could happen is if Microsoft or Google put the malware in the game streaming app itself, which is both ludicrous and should be prevented by the standard App Store review.

Apple put a blanket ban on these services supposedly because the company can’t review every game that is offered. But Apple doesn’t review content that’s distributed through Netflix, Kindle, Spotify, Amazon Prime Video, Hulu, or HBO, to name a few, and some of that content wouldn’t pass the App Store Review Guidelines if it were in an app.

Apple says the difference is that games are interactive. This doesn’t hold water either, because Netflix also distributes interactive video, including Microsoft’s own Minecraft: Story Mode. And even if an interactive video is somehow different from an interactive game, Apple currently allows other sorts of remote gameplay apps in the App Store, like Steam Link and PS4 Remote Play.

Granted, Apple also didn’t allow those apps for some time, but they effectively work the same way as Stadia and xCloud, the only difference being that the Steam Link and PS4 Remote Play apps stream games from a local game console over your local network rather than from a server on the Internet. Apple also allows remote desktop apps like Microsoft Remote Desktop which allow remote access to any sort of app. However, as John Gruber points out, Apple does put this distinction in writing in the App Store Review Guidelines 4.2.7:

The app must only connect to a user-owned host device that is a personal computer or dedicated game console owned by the user, and both the host device and client must be connected on a local and LAN-based network.

But Gruber also says that Apple’s official statement was nonsense. What’s the real difference between a host device on the local network and one that’s accessed over the Internet?

We also get into some murky philosophical territory here. What defines a “video game” and distinguishes it from a movie? Is Minecraft: Story Mode a video game? Could you consider books like the Choose Your Own Adventure series to be games? (I recall offshoots that involved dice rolls and other elements associated with “gaming.”) The 2013 app Gone Home sparked some intense debate over whether it was actually a video game. Must an artistic work exceed some threshold of interactivity to meet the definition of a video game, and can a video game even be considered art?

I can accept on some level that Apple could have good reasons to treat game streaming differently than books and movies beyond merely protecting its own business interests. But I can’t clearly define the distinction. As Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart said of obscenity, “I know it when I see it.” It might be more illustrative to use the more encompassing descriptor of interactive content, which may be easier to define.

The other argument in favor of Apple’s stance that I’ve heard is that Stadia and xCloud sell subscriptions or individual games outside of the App Store. But again, so does Netflix, and so do the Steam Link and PS4 Remote Play apps.

In a statement to Gizmodo, Microsoft responded to Apple’s decision:

Apple stands alone as the only general purpose platform to deny consumers from cloud gaming and game subscription services like Xbox Game Pass. And it consistently treats gaming apps differently, applying more lenient rules to non-gaming apps even when they include interactive content. All games available in the Xbox Game Pass catalog are rated for content by independent industry ratings bodies such as the ESRB and regional equivalents.

Microsoft could be an especially dangerous enemy right now. For whatever reason, the company seems to enjoy a favorable status with the federal government. Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella was not brought before Congress, despite Microsoft having a market cap on par with Apple’s. Microsoft was awarded the Pentagon’s lucrative JEDI contract over Amazon, although that’s being contested. Even more puzzling, the Trump administration is apparently assisting Microsoft in acquiring social video app TikTok from Chinese-owned company ByteDance.

Satya Nadella could easily appear before Congress and lay out the following facts:

- Apple blocks services like xCloud from the App Store.

- xCloud distributes interactive content.

- Netflix is allowed to charge a subscription fee to distribute interactive content without sharing a cut with Apple.

- The interactive content on xCloud is vetted and rated by the ESRB.

- Apple provides its own competing subscription gaming service, Apple Arcade.

If you’re a regulator, particularly one who doesn’t really understand the tech world, what conclusion would you draw?

Apple Has Devalued Apps

A much vaguer issue is the accusation, oft-repeated over the years, is that Apple, by providing so much software for free and encouraging inexpensive or free apps, has driven the price of software to near zero. Whereas developers used to be able to charge tens or hundreds of dollars for software packages, they now feel like they have to offer them at rock-bottom prices.

Making the problem worse is that Apple has prevented developers from charging for updates from day one. That forced developers to chase new customers instead of serving loyal users from whom they’d never see another cent.

Eventually, without allowing simple paid upgrades, Apple came up with a different solution: subscriptions. It feels like every app now offers or requires some sort of ongoing subscription. Subscription revenue is good for Apple’s Services business, and it provides steady income to developers, but users are frustrated by having to keep up with innumerable monthly bills and are left feeling as though they merely rent their software.

But how much of this is due to misguided or malicious Apple business practices, and how much is due to market realities? The very existence of the Internet has devalued many creative works—music being an infamous example. Apple is also often unfairly blamed for music becoming cheaper as well, but Napster was a thing long before the iTunes Store.

The simple fact is that the popularity of the App Store, and the relative ease of developing for it, have created a flood of apps. As the iPhone ad used to say, “There’s an app for that,” even for the most obscure use cases, and in reality, there are often multiple competing apps for any given task. Supply significantly outweighs demand, and the inevitable result is reduced prices.

We don’t have any proposed solutions here. The source of the issue is hard to pinpoint, and subscriptions have largely solved the upgrade problem for developers, even if users aren’t entirely happy about it.

Potential Solutions

The most likely path forward is for Apple to do nothing different until forced to change by a regulatory body. I say this is the most likely, because, from Apple’s statements, the company seems to think it has nothing to apologize for and feels that it is doing the world a favor in the way it’s running the App Store.

However, I think this would be a mistake that both the company and its fans would eventually regret. The sad truth, evident to anyone who watches Congressional hearings on tech, is that many legislators, even the younger set, do not have a firm grasp on the issues at play, much less on their subtleties. For example, Representative Jim Sensenbrenner asked Mark Zuckerberg, the CEO of Facebook, why Donald Trump Jr. was banned from Twitter, a completely separate and competing service. Oops! These are the sort of people who would be making the new rules.

A governmental solution already proposed by Senator Elizabeth Warren, who is probably better informed on these issues than most of her peers, is to split up Apple so that hardware, software, and the App Store are separate businesses. I think this would be a nightmare for both the company and its users. Imagine all the tight integrations we’ve grown accustomed to, suddenly at risk. Or worse, a spun-off company being purchased by Microsoft or another company. It’s hard to see a breakup solving these issues anyway since most of the complaints don’t revolve around Apple’s hardware and software having preferred status.

Another, more controversial solution would be for Apple to allow sideloading—being able to install apps in ways other than through the App Store—of apps in all of Apple’s operating systems. Some Apple users feel sideloading would confuse the user experience and worry that it would open up Apple’s platforms to bad actors. But the fact is that this system works fine on the Mac, and Apple still maintains some control over Mac software distributed outside the App Store. Despite the case of Charlie Monroe Software, it’s a system that gives developers flexibility and hasn’t resulted in the Mac drowning in malware.

It’s worth pointing out that enterprise users can already sideload their companies’ internal iOS apps, and there are alternative app stores out there already that take advantage of these tools that anyone can install with a bit of knowledge and chutzpah, no jailbreak required. You could argue that the sideloading problem has already been solved, but I think these alternative app stores survive largely because they remain below Apple’s radar. If an app distributed in such a way became a sensation, I suspect Apple would be quick to shut it down. My point here is that these systems are already in place and don’t seem to be hurting users; they simply require Apple’s blessing.

Alternatively, Apple could lower its rates, perhaps using a tiered system that would encourage the likes of Netflix, Basecamp, and Epic to take advantage of the better in-app signup experience. That one simple act would probably take a lot of heat off the company. However, with iPhone sales growth slipping and the Services segment becoming increasingly important, it’s hard to see Apple doing that voluntarily. The company is determined to maintain steady double-digit growth for Wall Street.

Finally, Apple could clarify its definition of “reader app” or eliminate the distinction altogether. Let any app use a payment system outside the app and let developers clearly state that in the app itself, so users don’t open an app to find a spartan login screen.

What Do You Think?

Are these concerns as big a deal as developers, media, and regulators seem to think? Register your vote in our quick survey, and tell us what you think Apple should do in the comments.

Quibble: Kagi was founded in 1994 (I was their first customer and signed contracts with them in August 1994).

I’ve been making a living selling Mac software online since then, and Apple comparing 2008 App Store sales to “bricks & mortar” shops as if that was the only solution is profoundly misleading and offensive. Gaslighting at its finest.

30% is a lot of money. If you deduct taxes then there isn’t a lot of money that remains for the developer.

As developer the whole “experience” of the AppStore process is a bad one.

Certificates: they work until they don’t work. Bad error messages. Too many certificates with different bad names.

Contracts: Apple decides that you need to sign new contracts. I get an email with a link. The contracts are at a different location. If you forget to sign the contracts you get a badly worded error message.

Review: I want to do a new dot release for my app. Reviewer is complaining about a feature that has been in the AppStore for months. Recently they decided that a specific function is bad. Every app that used the function was rejected with no prior warning. The best advice for getting through the review process is to just submit again to get a different reviewer.

Functionality: only severly castrated apps are allowed in the AppStore. AppleScript for Mail: no. Accessing data for Thunderbird or Postbox: no.

That usually (plus some arguments I’m not sure were actually read) was what worked for my free little iOS app (EncycloClip). Once I used the official appeal process, after a little chat with the executive who suggested a cartoonist “consider resubmitting” his rejected app after he won the Pulitzer prize. Another time my app was quietly approved after I posted a review noting that my update was being delayed.

Eventually my app was removed, in violation of Apple’s stated App Review Guidelines, because I hadn’t needed to update it. It seemed obvious that the rep just wanted me to re-post the app so that the mod time was updated, which I couldn’t do for unrelated reasons.

Thanks! Bloomberg has it wrong.

Kagi Inc - Company Profile and News - Bloomberg Markets.

Ben Thompson of Stratechery has, as usual, some well-considered points to make about the situation Apple is in.

In regard to the Epic lawsuit, he notes:

Nice article! Regarding streaming games, isn’t this the opening wedge for having much of your other interactive software running (mostly) remotely? Perhaps Apple is legitimately worried about the associated loss of privacy and control, and the bad user experience when the network connection is poor?

Thanks for the kind words, Norm. I mean, it’s possible, but Apple already allows many remote desktop apps. The tradeoff with game streaming apps like xCloud is that you deal with a bit of latency in exchange for running software on a device that couldn’t otherwise run it. Also, these services require tremendous data centers and other resources, because the games and the bandwidth requirements are about as demanding as it gets.

I don’t think it would make sense to distribute other types of software in this way.

You’re right, Josh, that this approach is probably only of specialized interest for the moment. And many apps already push their heavy lifting into the cloud. Still, this obviously reduces the incentive to make native versions of games for iOS, and creates new rules/monitoring/refund headaches for Apple. Nevertheless, I agree Apple is wrong here. This approach, with its strengths and weaknesses, should be allowed to compete.

I wonder how this will play out when Apple releases its much anticipated VR and AR headset and/or glasse? The rumors I’ve been reading about are currently pegging an early 2022 release date for a headset.