TidBITS#1232/21-Jul-2014

With his “Take Control of Apple TV” hat on, Josh Centers explains how the Apple TV’s Netflix client can now automatically play the next episode of a TV series when you finish an episode. Apple has launched a new iTunes Pass feature that lets you buy iTunes Store credit in a retail Apple Store via Passbook — we delve into what it’s useful for and how to set it up. Sitting too much may be killing us all, but the Stand Up work break timer could lessen the damage. Josh reviews it, as well as Marco Arment’s new podcast app, Overcast, which isn’t for everyone but brings welcome refinements to podcast listening. Michael Cohen tells the story of his involvement with the invention of the ebook, and how it almost fell prey to the curse of Macbeth. In this week’s FunBITS, Josh takes a look at The Rhythm of Fighters, a musical take on a fighting game mainstay. Notable software releases this week include DEVONagent Lite, Express, and Pro 3.8.1, Typinator 6.1, PDFpen and PDFpenPro 6.3.1, and Voila 3.8.

Apple TV Finally Gets Netflix Post-Play

Netflix has quietly added a feature to its Apple TV app that has been available on other platforms for years: Post-Play, which automatically plays the next episode of a TV series after the one you’re watching ends.

In my testing, the Post-Play screen didn’t appear at the end of every episode, so it’s possible that Netflix has yet to roll out the feature completely on the Apple TV.

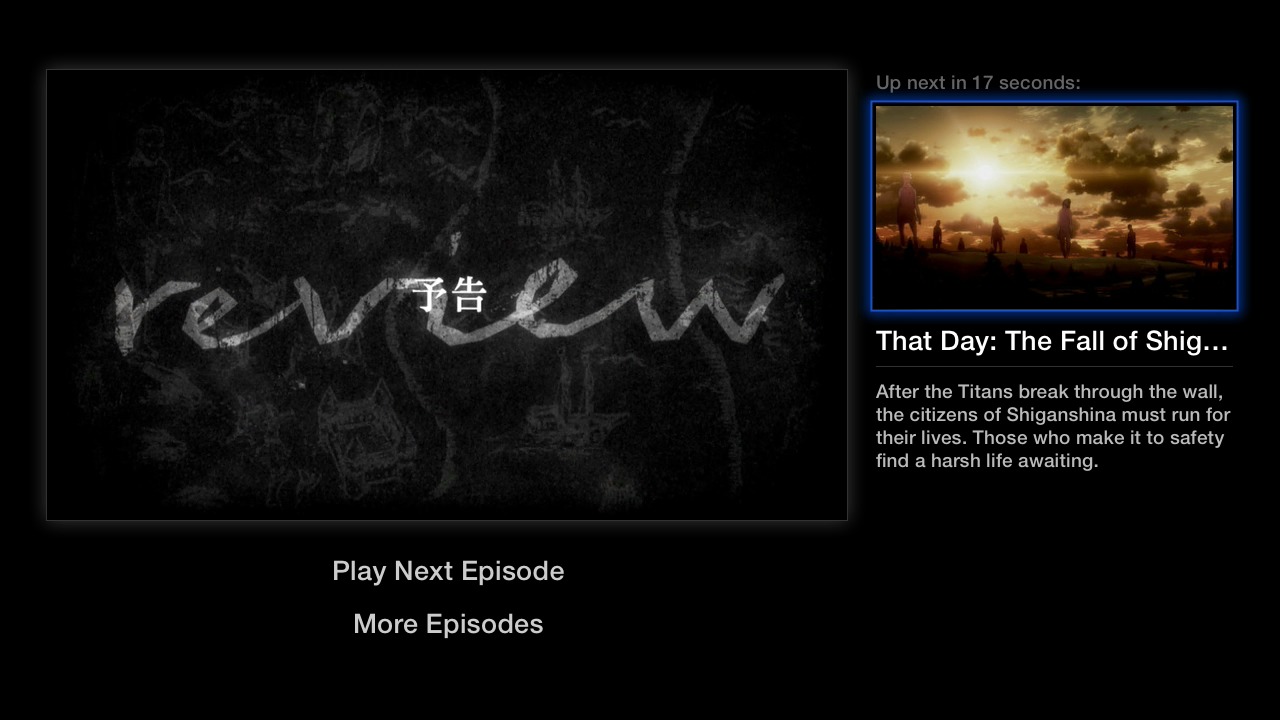

Here’s how it works: when you reach the end of an episode, Netflix switches to a special Post-Play interface, where the currently playing episode shrinks to the upper-left and a description of the next episode appears on the right. By default, the next episode starts playing in 17 seconds, but you can play it immediately by selecting Play Next Episode, or return to the episode list with More Episodes. You can also press the Apple remote’s Menu button to exit Post-Play.

After playing two episodes automatically, Netflix asks if you’re still watching, which is sensible.

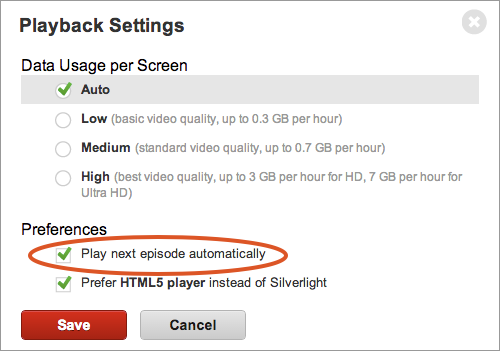

If you don’t like Post-Play, you can turn it off in your Netflix account, in the Playback Settings screen, by deselecting Play Next Episode Automatically.

For more tips to master your Apple TV, check out my book, “Take Control of Apple TV,” and its free cheat sheet.

iTunes Pass: How to Buy iTunes Store Credit via Passbook

We previously reported that Apple was testing the new iTunes Pass service in Japan (see “Apple Testing iTunes Pass in Japan,” 15 July 2014). The service, which lets you purchase iTunes Store credit in a retail Apple Store via Passbook, is now available in the United States.

With it you’ll be able to load up an iTunes account with funds you can use to buy iOS and Mac apps, iTunes music and videos, and books from the iBooks Store. We see two primary use cases for iTunes Pass, both revolving around iTunes Store accounts without credit cards already associated.

- You could set this up on a child’s iPhone or iPod touch, then either use that device in an Apple Store or share its Passbook card with your iPhone (tap the share icon on the card) so you could add money to it in an Apple Store without needing the child’s device.

- If you don’t have a credit card (something that’s true of about 23 percent of the U.S. population) or refuse to associate a credit card with your iTunes Store account, iTunes Pass would enable you to buy iTunes Store credit with cash in an Apple Store. (More generally, it would be good for cash-oriented cultures, but we suspect most countries with Apple Stores are well along in credit card adoption.)

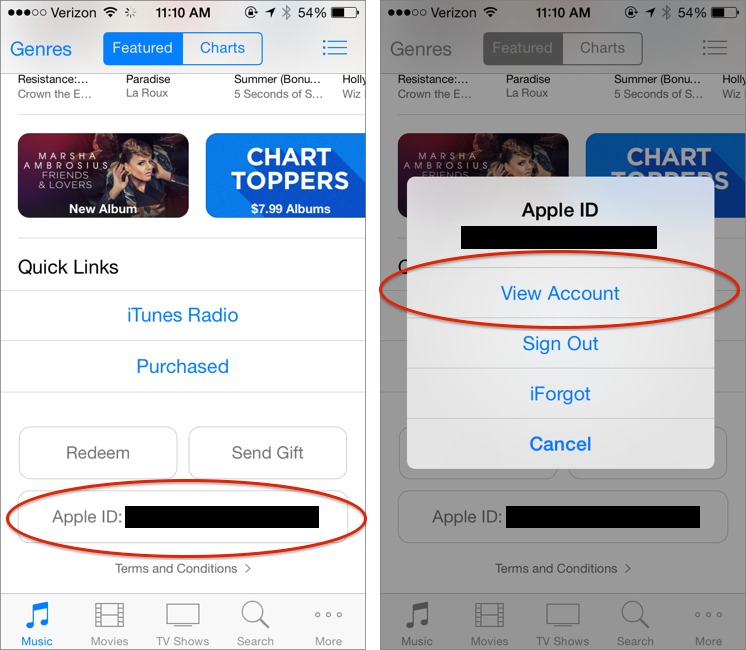

To add iTunes Pass to your Passbook app, open the iTunes Store app on your iPhone or iPod touch (this won’t work on the iPad, likely because it doesn’t have the Passbook app), scroll down to the bottom, tap the Apple ID button, and tap View Account.

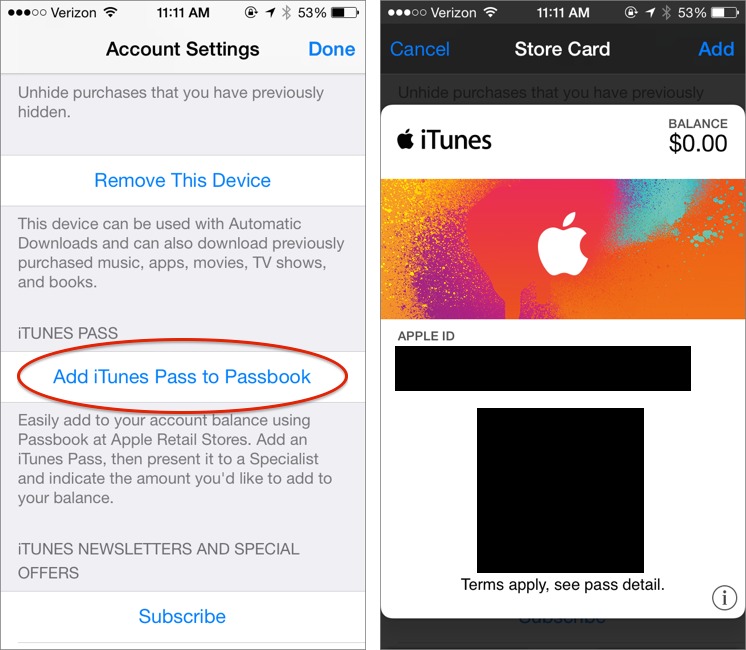

Enter your iTunes password, if prompted, then scroll down and tap Add iTunes Pass to Passbook. You’ll be presented with the iTunes Pass to verify that it has been added.

Now, while in an Apple Store, open the iTunes Pass card in Passbook, flag down a Specialist, tell her that you’d like to add credit to your account, and show her the card on your device. Presumably you’d then need to pay for the credit with cash or a credit card.

If you want to delete iTunes Pass, open the card in Passbook, tap the information button in the lower-right corner of the card, and tap Delete in the upper-right.

Stand Up! The Work Break Timer that Wants to Save Your Life

Sitting is killing us. Study after study has linked extended periods of sitting to cancer, diabetes, and heart disease, and we presume tooth decay and the moral decline of society will be on the list soon. Unfortunately, even exercise doesn’t offset the harm done by sitting.

“A consistent body of emerging research suggests it is entirely possible to meet current physical activity guidelines while still being incredibly sedentary, and that sitting increases your risk of death and disease, even if you are getting plenty of physical activity,” Travis Saunders, a Ph.D. student and certified exercise physiologist at the Healthy Active Living and Obesity Research Group at Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario told Runner’s World.

The common answer to the hazards of sitting is a standing desk, or even a treadmill desk, but not everyone can take advantage of those. Most people work in offices where they have little say over what kind of equipment they can use. Some people have health issues that prevent them from standing all day. Others, like yours truly, can’t concentrate well while standing.

Fortunately, research shows that standing up and moving around every 20–30 minutes offsets the damage done by sitting. You could manually set a timer to remind you to stand up, but I’ve found a free solution to make it even easier: the Stand Up! app by Raised Square LLC. It runs on your iPhone, so you can use it at your home or office.

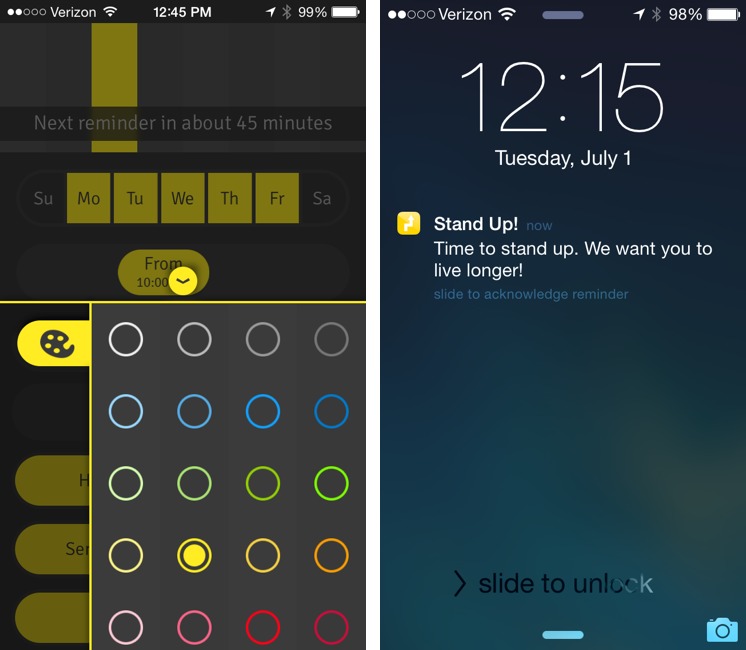

Stand Up does one thing and does it well. Open the app, select which days you would like alerts on, set a time range for those days, set an alert interval, and if you choose, even set alerts to work only at your current location so it doesn’t nag you when you’re out of the office. For a 99-cent in-app purchase, you can choose from a selection of alert sounds, though the free default is perfectly audible and pleasant.

By default, the app features a yellow theme, but if you wish, you can change it to a number of other colors. Not that it matters much; after setting your preferences in Stand Up, you won’t be spending much time in the app. Now, every few minutes (45 by default), you’ll receive a notification on your iPhone telling you to stand up. If you’re in a meeting or other situation where suddenly popping to your feet would be inappropriate, you can tell Stand Up to remind you again later, and there’s also an always-visible graph that shows how many

reminders you’ve explicitly acknowledged. Simple, and effective.

It does seem that Stand Up could make use of the iPhone’s accelerometer, both to acknowledge alerts automatically and to reset the timer if you stand up on your own before being alerted. Perhaps a future version will add some additional smarts in this area.

I’ve been using Stand Up for a few weeks now, and I’ve noticed less pain in my back and posterior. There are a lot of reminder apps out there, but Stand Up is free, well-designed, and can be taken anywhere. In addition to that, it might extend your life.

Overcast Refines the iPhone Podcast Experience

Marco Arment may have helped develop the microblogging service Tumblr (currently owned by Yahoo) and gone on to create the read-it-later service Instapaper and the biweekly electronic publication The Magazine, but in the last few years he has become most famous for his podcasts: first the now-retired Build and Analyze with co-host Dan Benjamin and now Accidental Tech Podcast with co-hosts John Siracusa and Casey Liss.

It was only natural that fans of his podcasts — yours truly included — bugged Arment to build a podcast app of his own. (I’ll cop to being obsessive about podcast clients. See “Five Alternatives to Apple’s Podcasts App,” 22 December 2012, and “Instacast for Mac Fills the Desktop Podcatcher Gap,” 31 May 2013.) But what we didn’t know was that Arment was already working on one, and had been since October 2012. After selling off Instapaper to Betaworks (see “Betaworks Takes over Instapaper,” 25 April 2013) and The Magazine to our own Glenn Fleishman (see “Glenn Fleishman Buys The Magazine from Marco Arment,” 29 May 2013), Arment had freed up the time to develop it, announcing Overcast in September 2013 at the XOXO Festival. It’s now available for free for iPhone in the App Store, with an optional $4.99 in-app purchase.

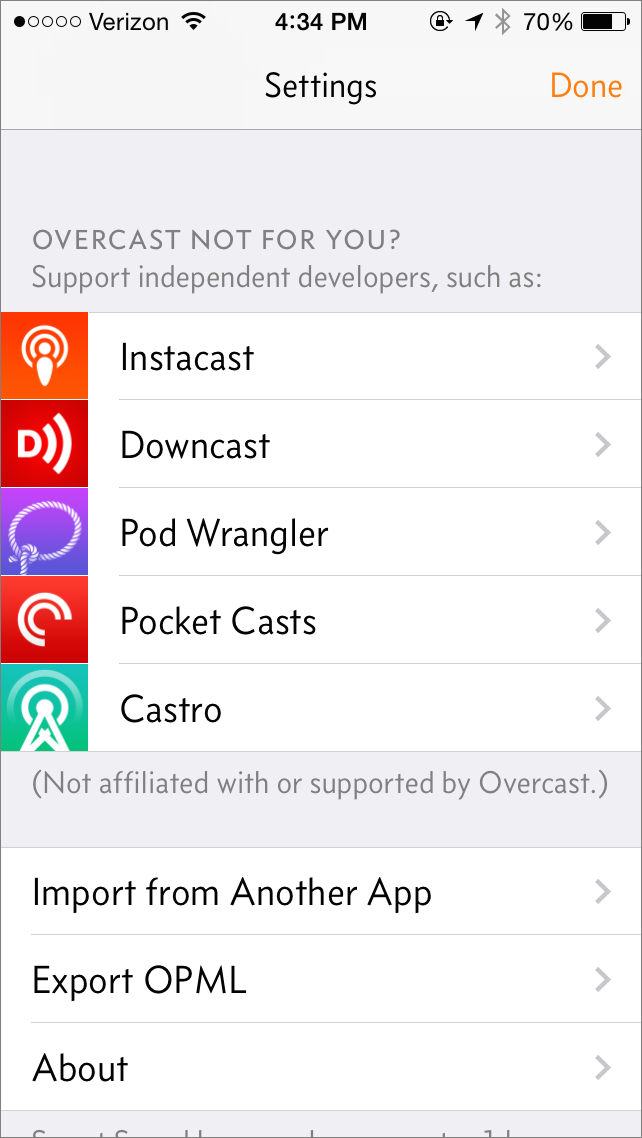

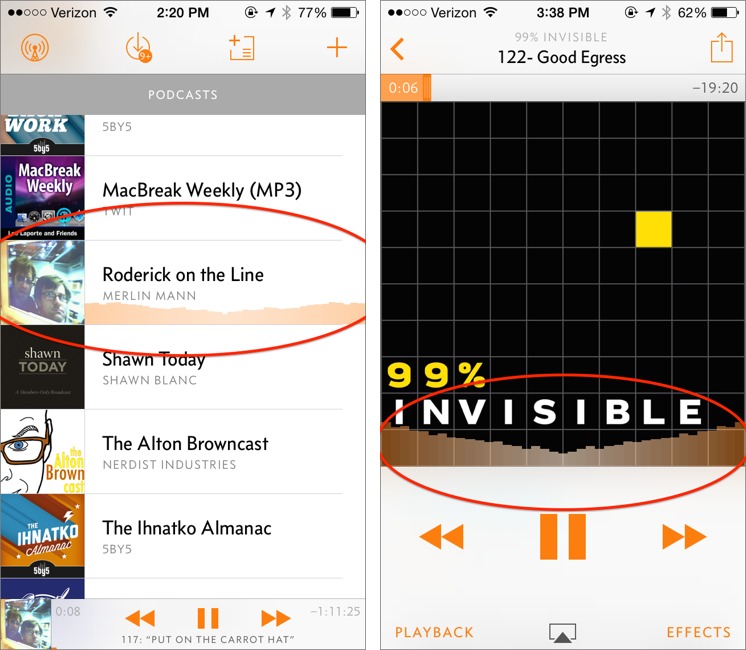

Overcast may be the most hyped podcast client ever, but Arment isn’t seeking to revolutionize podcasting. Rather, he created Overcast to satisfy his own podcast listening needs. If it happens to work for you as well, all the better. Arment freely admits that Overcast may not be for everyone, even going so far as to link to other podcast clients in his app’s settings.

That said, Overcast brings a number of welcome refinements to the podcast listening experience, along with a nicely designed user interface that makes it easy to control without requiring much visual attention.

Server-side Sync — Podcast clients are, at their core, RSS clients. The way most work is by checking each subscribed feed, one at a time, at a set interval.

While obvious, this approach is woefully inefficient, as the client must connect to a different server to get new episodes of each podcast. To reduce this unnecessary work, Overcast borrows a feature from Shifty Jelly’s Pocket Casts, instead relying on a single server to aggregate and cache new podcast episodes (Arment had help from Shifty Jelly’s Russell Ivanovic in developing Overcast).

Although this approach requires you to create a free account before using Overcast, it enables Overcast to use less battery power and receive new episodes faster than many other podcast clients. For instance, in my testing, Overcast typically received a new podcast episode 30 minutes before Instacast.

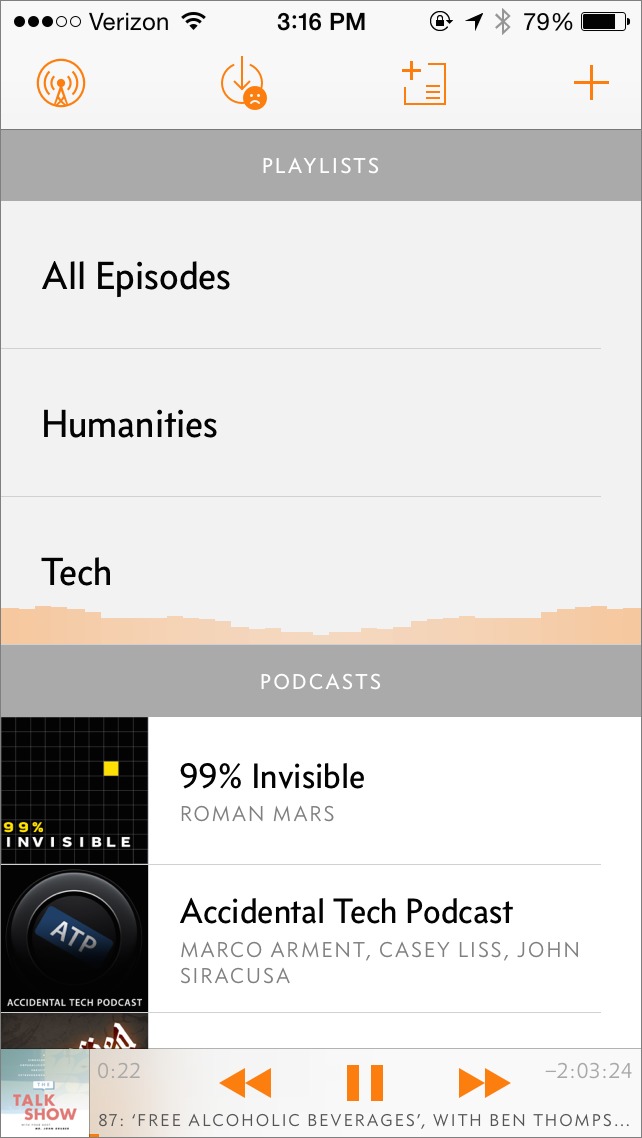

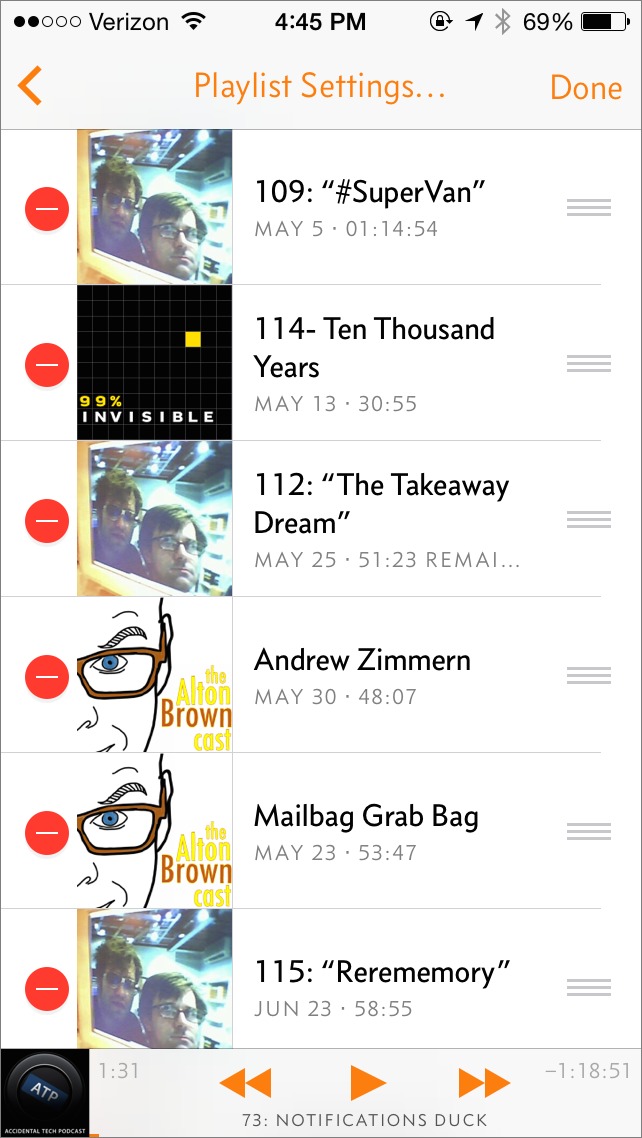

Proper Playlists — One podcast client feature I almost always ignore is playlists. In theory, they’re great for grouping podcasts on similar topics so you can listen to a bunch of related episodes, one after another, without fussing with your iPhone in the car. Alas, in practice, playlists are either buried deeply in the interface or are too difficult to manage.

Overcast has the first podcast playlist system I feel inclined to use, thanks to easy access, well-considered options, and the capability to rearrange episodes manually.

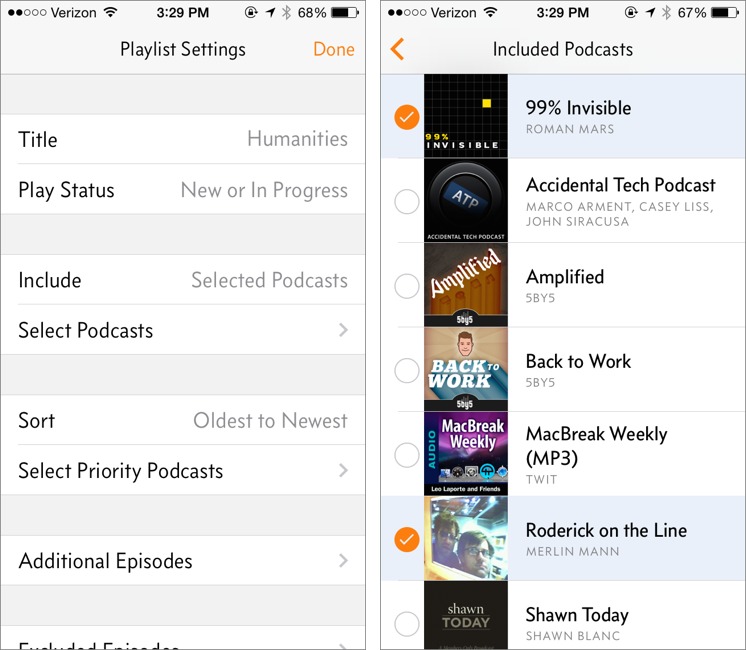

Playlists appear on the main screen, alongside individual subscriptions, so they’re easy to find, and they’re just as easy to create and manage.

To create a new playlist, tap the Add Playlist button, the third button from the left at the top of the screen. Give the playlist a name, then select which podcasts to include (or exclude), as well as other episodes to include or exclude individually.

You can also choose how to sort podcasts and select podcasts to prioritize in the playback order. But what I most like about how Overcast does playlists is that, while a playlist is selected, you can tap edit in the upper-right of the screen and manually rearrange episodes to your liking.

The free version of Overcast allows only a single playlist that displays the top five episodes. Full playlist functionality requires the $4.99 in-app purchase.

Here’s a bonus feature. With playlists and subscriptions taking up the main screen, you may wonder how you can tell what’s playing at the moment. To help make it obvious, Arment has placed a neat waveform animation over the currently playing playlist or show. You can also see that animation on the playback screen, at the bottom of the show art.

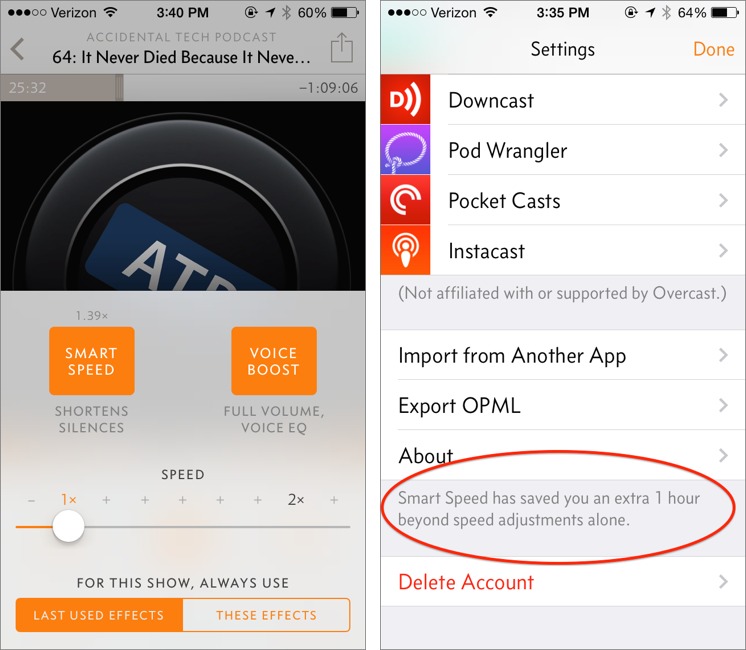

Smart Speed and Voice Boost — Perhaps the only downside of trading my day job and 100 mile commute for working at home on TidBITS is that I don’t have nearly as much time to listen to podcasts. That’s why I appreciate Overcast’s Smart Speed feature.

Overcast, like most podcast clients, can be set to speed up playback, but this makes your favorite podcast hosts sound like chipmunks. Overcast’s Smart Speed feature instead shortens silences, reducing playback time without any noticeable difference in audio quality.

I was initially dubious that this could save much time, but it turns out to be a surprising amount. To make sure you realize what it’s doing, Overcast reports on how much silence it has skipped in the Settings menu. In the past week or so, even without listening to too many shows, I’ve saved an hour, which is significant.

Being able to listen to more podcasts in less time with no drawbacks in audio quality is a killer feature. But just as good is Overcast’s Voice Boost audio effect, which is an equalizer that highlights vocals. It makes a huge difference when listening over teeny iPhone speakers.

Smart Speed and Voice Boost require the $4.99 in-app purchase, though you can try both for five minutes without charge.

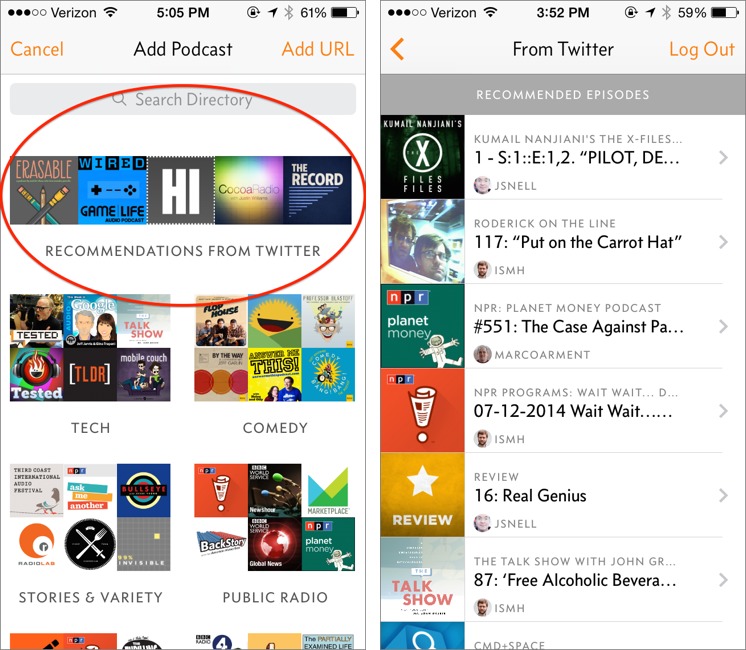

Recommendations from Twitter — If you tap the Add Podcast button in the top-right corner, you’ll see the standard searchable podcast directory that’s in every podcast app these days, highlighting some of Arment’s favorites. But if you link up your Twitter account, you’ll see a Recommendations from Twitter category at the top, with episodes and shows tweeted about by those you follow on Twitter.

This is a great way not only to discover new podcasts, but also to discover great individual episodes. I’d love to see a future update that includes curated playlists, like Beats Music, with collections of recommended episodes from individual contributors.

But It’s Not for Everyone — What’s not to like about Overcast? People have different desires when it comes to podcasts, which is why there are so many clients in the App Store. Unfortunately for me, Overcast lacks a few features that prevent it from replacing Instacast as my client of choice.

Overcast doesn’t do streaming at all. An episode can’t be played back until it has been downloaded. I understand why Arment chose to leave this out, as streaming is finicky and tough to get right. If you often listen to podcasts while on the road, downloads are better, since playback can stop (or do stranger things) when you pass through an area with poor cellular connectivity. But for someone like me who is often at home, streaming is preferable, since I don’t have to waste bandwidth and storage space automatically downloading episodes I may or may not listen to.

That leads to my next complaint, which is that Overcast, unlike Instacast, can’t limit how much storage it uses. While Overcast does warn you when your iPhone’s free space falls under 200 MB, it happily keeps downloading podcasts until your iPhone is full. To manage storage, Overcast provides only a limited set of tools: you can unsubscribe from shows, change how many to keep (two by default), or delete episodes manually.

In a way, Overcast forces you to choose which shows you’ll actually listen to, instead of my inefficient method of subscribing to 40 podcasts and listening to only a handful. Perhaps a future version of Overcast could suggest shows to drop, based on how little the user listens to them?

My final problem with Overcast is that it’s mostly tied to the iPhone. I prefer listening to podcasts from my Mac, so I don’t miss any notifications or system sounds while using earphones. Also, a Mac app could provide keyboard shortcuts for faster interaction than is possible on the iPhone. Arment has a rudimentary Web app available, but it offers bare-bones functionality. An iPad app is in the planning stages, and he’s considering creating a Mac app in the future.

Who Is Overcast For? — I’m sad that Overcast isn’t for me, because it’s a beautifully designed podcast client with numerous well-considered features. But I fully accept that I am now an unusual podcast listener, given that I rarely leave the house.

Most people listen to podcasts while on the go — commuting, walking the dog, or running — and for those folks, Overcast is a great client. When I was listening to podcasts while driving, I would have especially appreciated Overcast’s oversized playback buttons, which are handy when you need to play or pause an episode with a minimum of eye contact. Voice Boost would also have been handy when my cantankerous Bluetooth FM transmitter flaked out.

If you’re unsatisfied with the current slew of podcast clients, try the free version of Overcast to see if it’s right for you. If not, you can always check out one of the other podcast clients that Overcast itself recommends — they’re all pretty good.

The Birth of the Ebook

We had trouble finding the door.

It was a late spring day in 1990. Professor Richard A. Lanham of UCLA and I stared up at the ocean-facing building’s decaying balconies and rusted ironwork. Sand swirled at our feet. “I think it’s down here,” I said, looking down a shadowy walkway that led away from the beachfront path with its distant rumble of heavy surf and out to the Pacific Coast Highway with its deafening roar of heavy traffic. Midway along the building’s side we found a determinedly unprepossessing door. We stopped. I shrugged and pressed the buzzer by the door. Several long moments later, it opened. We had found the Voyager Company.

Voyager had invited Lanham to attend a one-day meeting about computers and text, and Lanham asked me to tag along. Lanham was something of a big name in the nascent field of computers and text: a few years earlier, he had completely revamped UCLA’s composition courses, and his new Writing Programs introduced computer technology to undergraduate writing instruction. (Yes, “Writing Programs” is plural; the organization that Lanham established managed several different writing programs.)

I was his technical advisor, anointed with the bizarre payroll title of producer/director. He hired me because my computer program, Homer — which I had begun developing while still in graduate school — had evolved into one of the computer tools used in the Writing Programs classes. Although both he and I had largely moved on from the Writing Programs by then, we had stayed in touch, and it felt right that I would reprise my tech advisor role.

Meanwhile, Voyager, known for its Criterion Collection laserdiscs, had just made big waves in the tiny digital media world when it released its groundbreaking CD-Companion to Beethoven’s 9th Symphony. The Companion, authored by UCLA Professor Robert Winter, married a HyperCard stack to an audio CD recording of the symphony. Designed to run on those few Macs that had CD-ROM drives, it offered all sorts of interactive historical, musicological, and biographical information about the work and

its composer, and even included a running text commentary synced to the CD recording.

Voyager’s president, Bob Stein, had obtained some grant money to explore whether anything comparable to a CD-Companion could be created for literature, and the grant paid to bring several digital text luminaries to Voyager’s Santa Monica beachfront offices to hash out the possibilities. Lanham and I were among the cheap invites: UCLA lay just a few miles inland, so in our case Stein only had to pay our parking and give us a free lunch.

Neither Lanham nor I recall many details about that Bloomsday meeting. He mostly remembers the outré attire — to him — of the Voyager staff. I remember that at least one dog roamed free through the ramshackle offices: we were warned to watch where we stepped. I also recall a long discursive conversation that eventually crystallized into two factions with two distinct visions of the future of digital text. One group proclaimed that text’s future was full-on hypertextuality and the long-awaited death of linearity; the other group saw a future of the Book Renewed, revitalized by all the adornments that digital technology could provide.

Stein (and Lanham and I) fell into the Book Renewed camp. We all agreed that simply putting an ordinary book on the screen was a non-starter — digital text would have to be interactive in some way because the physical experience of reading on even the best desktop computer monitors of that era was less than delightful.

At the end of the meeting, Stein offered me a job. I thought he was joking. Eight months later I found myself being interviewed by Jane Wheeler, who managed the programmers, producers, and artists at Voyager.

Stein had decided that a CD-Companion-like treatment of a Shakespeare play would be perfect for cracking the nut of digital text, and, of the plays, one of the big four — Hamlet, Othello, King Lear, and Macbeth — would make the loudest crack. Of those, he picked Macbeth: among its other benefits, it was the shortest of the four. (Slightly more than 2,100 lines in most editions; by comparison, Hamlet has almost twice as many.) My job was to produce this digital book.

The Expanded Books Project — The first couple of months I continued to work part-time at my UCLA job while sketching out rough ideas for the Macbeth Companion. By summer I had a lot of false starts behind me. Then one day I showed up at Voyager and found everyone buzzing about a review unit of the as-yet unreleased PowerBook 100 that Apple had loaned Voyager. The sleek (5.1 pounds or 2.3 kg!), powerful (2 MB of RAM!), portable Mac with its amazingly spacious screen (640 by 400 pixels!) was passed lovingly from hand to hand.

Florian Brody, a loquacious Austrian with a background in computer science, film, and linguistics, had put a couple of pages of “The Sheltering Sky” on the PowerBook, turned it on its side, and asserted, “This looks like a book!” You could almost see cartoon lightbulbs flaring over people’s heads.

Within weeks, the Macbeth Companion was put on hold and I began working full-time at Voyager on the quickly coalescing book project. In the hallway outside of Wheeler’s office, meeting after meeting took place, or perhaps it was one long meeting that ran for days, ensnaring anyone — artists, coders, even the receptionist — who happened by.

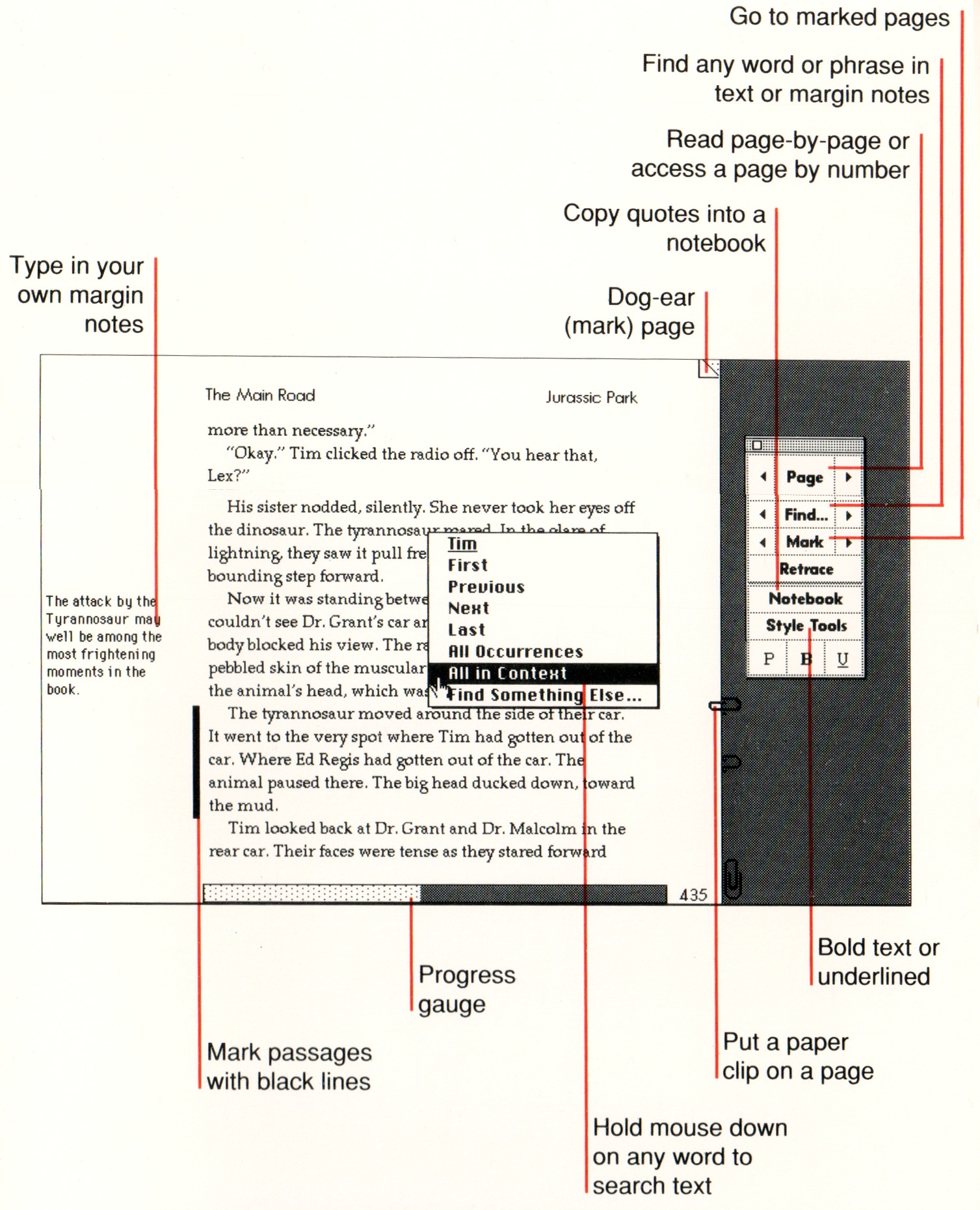

We hashed out the details of what kind of digital book we could make, how it would look, what features it would have, even what the format would be called. It was inevitable that the general term would be “e-book,” but we argued for days about what the “e” stood for before we decided that it stood for “expanded.” Many of the standard features of today’s ebooks, including bookmarks, margin notes, and page gauge, first saw the light of day in that hallway.

We built the books on top of Apple’s HyperCard, Voyager’s platform of choice. Colin Holgate, a soft-spoken, compact Brit with an unparalleled talent for making HyperCard do astonishing things, took on scripting the book shell (that is, the empty HyperCard stack into which the book’s contents would be “flowed”). Voyager’s small art department provided a clean,

book-like page design. I laid out the text, using utility scripts that Holgate created to “flow” a book’s text into consecutive pages. As the number of scripts multiplied, I also created a hidden Magic button in the book shell that presented an ever-growing menu of Colin’s scripts (and some of my own) so I could readily invoke them at need. (When I eventually got around to Macbeth, I gave it its own, much more complex Magic button — it may still be there in some early releases of the CD-ROM if you know where to look.)

The first three Expanded Books slowly came into being that fall in a small office by the stairwell on Voyager’s second floor. Copies of the in-progress EBs (as we called them) were regularly loaded on the PowerBook, which Stein had begun to travel with. One day, he returned from a business trip to inform us all smugly that he was the first person in history to have read an EB in the restroom of a jetliner in flight.

By the time the San Francisco Macworld Expo rolled around in January 1992, the first three EBs were ready. They were loaded on floppy disks and packaged in stunning paperback-like packaging designed by Voyager artists. We made it just barely in time: even two days before the show, Stein still wanted to make major changes to the EB interface, but I was ready to get back to work on Macbeth.

The Toolkit and Other Distractions — The EBs were a big hit at Macworld. I spent hours at the Voyager booth, demoing them to hundreds of people, including one very tall, very genial fellow with a plummy BBC accent who turned out to be Douglas Adams; his collected “Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy” novels were one of the EBs. I told him about Macbeth; he suggested I follow it up with something by Chaucer and recommended a book about “The Knyghtes Tale” by a friend of his, Terry Jones. (Yes, that Terry Jones. The book is “Chaucer’s Knight: The Portrait of a Medieval Mercenary.”

It’s both readable and scholarly; I highly recommend it.)

But I couldn’t return to Macbeth after the Expo. Stein had promised that Voyager would produce an EB toolkit so other publishers could adopt the format, and work on that project ramped up almost immediately. Voyager programmers Brock LaPorte and Steve Riggins were drafted to write external C routines for the Toolkit to provide capabilities beyond what HyperCard, even with Holgate’s clever scripts and my Magic button, could manage on its own.

I wrote the Toolkit manual and the book-building tutorial. The example text I passive-aggressively chose for that was Chapter 94 of “Moby-Dick,” the “sperm-squeezing” chapter, much to Stein’s amusement and the embarrassment of almost everyone else at Voyager.

At the same time, I was assigned to do post-production work on a CD-ROM version of Adams’s book about endangered species, “Last Chance to See.” Macbeth languished that spring and summer, wandering in Birnam Wood.

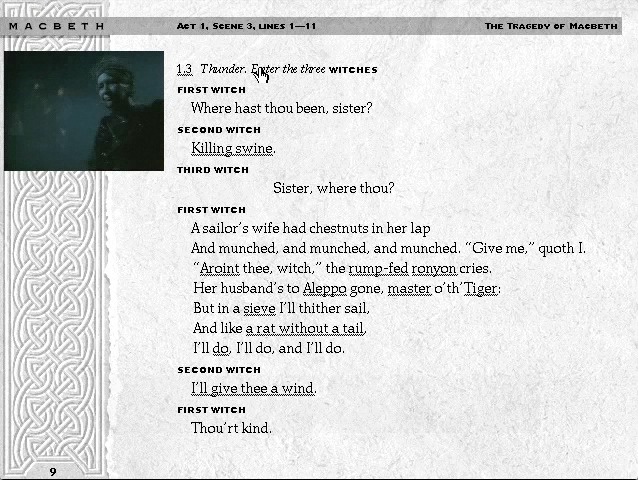

Back to the Highlands — We finished the Expanded Book Toolkit in time for the Boston Macworld Expo that August, and at last I could return to the Scottish play. In the interim, I realized that Macbeth would not be a CD-Companion but, rather, an example of the next stage of the Expanded Book. (In fact, even as I was finishing Macbeth I was also adapting its HyperCard shell so it could be used in other projects. One such was a Voyager CD-ROM edition of the film “Salt of the Earth.”)

Voyager finally assigned some resources to the project. Chief among them was Brian Speight, a graphic artist at Voyager who created beautifully elegant Celtic-interlace page backgrounds for the program along with maps of Shakespeare’s London and Macbeth’s Scotland.

Stein had already contracted with UCLA professors to write the text: David Rodes, who had wildly popular undergraduate Shakespeare courses, in part due to his own élan as a presenter, and in part to his habit of inviting professional actors, some of them his friends, to perform scenes in class. Rodes wanted more scholarly depth on the bench for Macbeth, and suggested Al

Braunmuller, also a popular classroom teacher, then editing Macbeth for a new Cambridge edition of the play. Braunmuller agreed to produce original essays for the project and to provide an authoritative play text.

Rodes, Braunmuller, and I agreed on a table of contents for the disc; Braunmuller began delivering both play text and essays; Rodes wrote an introductory essay along with act and scene headnotes; and we started to acquire copyright permissions for the picture gallery that would be included.

We still hadn’t picked a performance to sync with the text. I viewed every video production of the play I could lay hands on — the most laughably idiosyncratic starred the otherwise fine actor Jeremy Brett — but we eventually chose Rode’s original pick, a Royal Shakespeare Company performance directed by Trevor Nunn, starring Ian McKellen and Judi Dench.

Voyager video specialists began digitizing a master videotape of it we obtained into 160 by 120 resolution QuickTime video — tiny but watchable; anything larger would take up more space than a CD-ROM could store. They also digitized scenes from three movie adaptations to complement the main performance: Roman Polanski’s and Orson Welles’ versions, along with Akira Kurosawa’s “Throne of Blood.”

Our plan also included a game: a “Macbeth Karaoke” that would enable readers to perform some scenes opposite professional actors. We recorded these karaoke audio tracks in Rodes’s house in the hills above West Los Angeles, with me perched on the daybed in Rodes’s study, digital audio recorder on my lap, while two actor friends of Rodes did take after take of several scenes between Lord and Lady Macbeth, pausing whenever airplanes flew over.

By winter’s end, Macbeth had three complete scenes, including two levels of annotations, and enough accompanying material to be demoed at the open house evenings that Voyager regularly held. Psychedelic explorer Timothy Leary was a guest at one such open house: he repeatedly insisted to me that we had met before (we hadn’t — not, at least, on this astral plane).

When Macworld Expo in Boston rolled around again that summer, I gave the ultimate demo: a performance of the Macbeth Karaoke before thousands of people, staged in the big tent used for the Expo keynote. It was well-received, though neither Broadway nor Hollywood came knocking at my door.

A Walking Shadow — Actors will tell you that Macbeth is a bad luck play, one whose very title you utter at your peril.

We had already been mildly hit by the curse once. In David Rodes’s introduction to the play, he mentioned that the title character in the film “Ghost” was on his way home from a performance of Macbeth when he was murdered. We wanted to illustrate that part of the introduction with a picture of the newspaper advertisement for the movie, but the cost of procuring rights to use the ad were too high.

Now, though, the curse came into full play.

First, at the post-Macworld Expo dinner, Stein crushed everyone’s celebratory mood with an after-dinner speech full of gloom and portents — despite our Expo success, Voyager was facing hard times, and we would all have to work much harder than ever before to make it through them. A few weeks later we discovered that the Santa Monica offices were to close and the company would relocate to New York City at the end of the year, ostensibly to be closer to the center of the publishing industry.

I was encouraged to uproot stakes and move to New York, but, with all my family and friends in Southern California, I elected to stay and finish the CD-ROM in Santa Monica, working remotely with Voyager via modem and phone from my apartment. In February, the 1994 Northridge earthquake struck, destroying the old Voyager beachfront building, and nearly wrecking my home office — it took almost a week to get the office in working order again.

The big blow, though, was when Stein informed me that rights negotiations with the Royal Shakespeare Company had hit a snag: they wouldn’t approve the use of the video unless we made it much larger, a technical impossibility at that time. As a sop, the RSC did, however, grant us audio rights to the performance. I rewrote the text-synchronizing code so that it would work with an audio-only track. Given all the material we had to leave out of the CD-ROM in order to accommodate the complete video, this development, so late in production, was heart-breaking.

At about the same time, Stein informed me that I would really need to live in New York to contribute to future Voyager projects: he did not think it was feasible to maintain a remote West Coast office with a single employee.

So it was that, two weeks shy of the four-year anniversary of that first meeting in Santa Monica, and with the CD-ROM all but finished except for final QA testing, I emailed Stein my resignation.

This time, I had no trouble finding the door.

(This article originally appeared in slightly different form in issue 32 of The Magazine, 19 December 2013. Used with permission.)

FunBITS: The Rhythm of Fighters Beats the Beats

I’ve written extensively about the challenges of adapting traditional game genres to touch screens (see “FunBITS: Leo’s Fortune Perfects Touchscreen Platforming,” 27 June 2014). Perhaps no genre is worse served in the age of touch than that of the fighting game, where two characters square off on screen, jumping around and exchanging punches, kicks, and other attacks.

Not that it hasn’t been tried. Capcom adapted Street Fighter IV to the iPhone with onscreen controls, but the result is laughable. While fighting games seem simple on the surface, they may be the most difficult genre to master. Anyone can mash buttons for frenetic gameplay, but advanced tactics like special moves, combos, and counters require absolute precision, so much so that even gamepads aren’t quite good enough. Dedicated players often shell out for arcade-style fighting sticks to reach that level of precision.

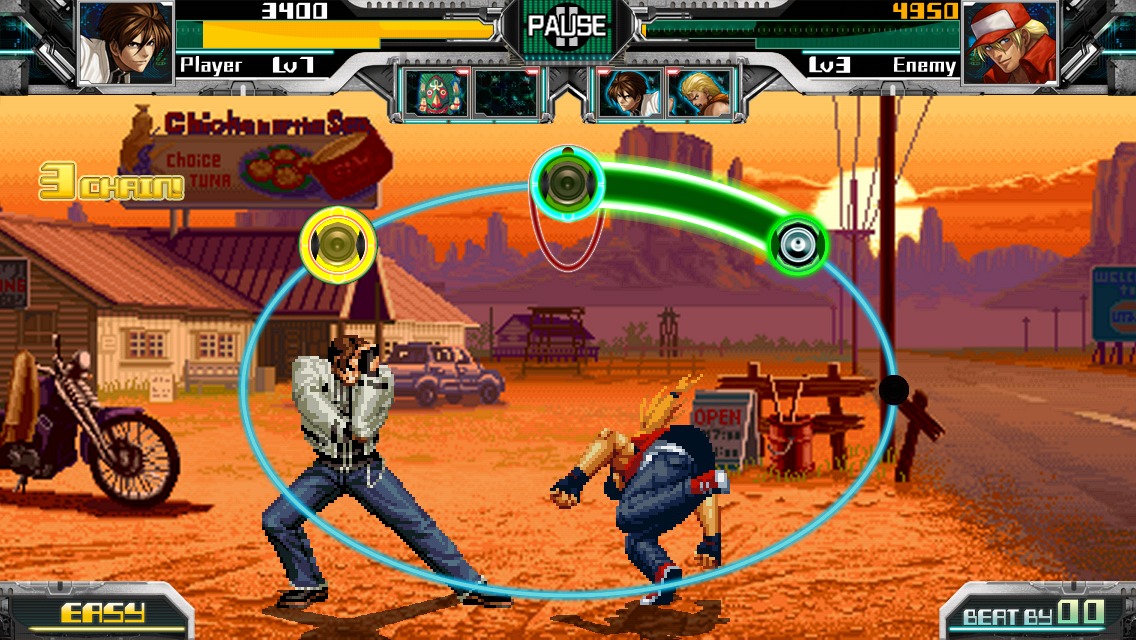

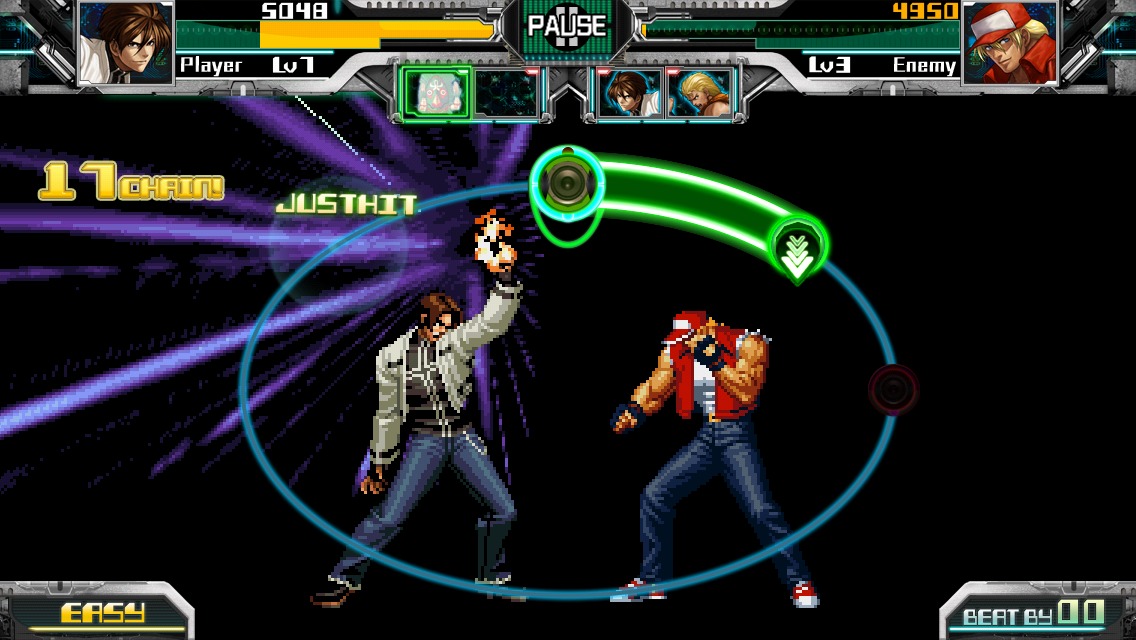

But someone at SNK Playmore, developers of the fighting game series The King of Fighters, had a crazy idea: what if you merged a fighting game like The King of Fighters with a rhythm game, like Dance Dance Revolution or Rock Band? The result is The Rhythm of Fighters for iPhone, available for $0.99 in the App Store (42.7 MB, iOS 7). Here’s a video showing how the game works.

To be specific, The Rhythm of Fighters is the merger of a fighting game and the Nintendo DS classic, Elite Beat Agents, and if you’ve played that game, you’ll find the gameplay of The Rhythm of Fighters to be virtually identical. Check out a gameplay video of Elite Beat Agents to see how similar the two are.

Each of the game’s 50 stages is set up like a traditional fighting game. Your character squares off in an arena with an opponent, attempting to land blows that will drain the other’s health bar. But instead of mashing buttons to perform attacks, you tap onscreen circles, called Notes, in time with the beat of the background music.

There are several kinds of Notes that require different invocations, resulting in different fighting moves. You activate Tap Notes by simply tapping the screen. But timing is key. An outline appears outside of the Tap Note and shrinks around it. The right time to touch the screen is when the outline meets the edge of the Tap Note. Then there are Flick Notes, which are like Tap Notes, but specify a direction to flick instead of tapping. Most important to master are Long Notes, which follow along an onscreen track. You

must first press at the right time, then release when the Long Note reaches the end. Perfectly executing a lengthy Long Note unleashes a devastating combo on your opponent. Some Long Notes also end in a Flick Note, so you have to stay alert.

But knocking out your opponent isn’t actually the objective of The Rhythm of Fighters. Instead, you’re trying to prevent your opponent from knocking you out for as long as the music plays. Successfully attacking your opponent prevents her from hitting you, but missing Notes leaves you wide open to attack.

The main problem I’ve encountered is that my taps are occasionally ignored, causing me to miss Notes and absorb punishment my character doesn’t deserve. I hope this frustrating bug can be resolved in a future update.

While fans of The King of Fighters may be thrilled with this game, I find the fighting game aspect a distraction, since the fight has little to do with the gameplay. While the concept is interesting, it could be so much more. For example, two-player fights are a must in a fighting game, but The Rhythm of Fighters offers no multiplayer option, which would have made the game unique.

However, The Rhythm of Fighters does offer some unusual aspects that add depth. There’s a leveling system, which makes your character more powerful as you play each stage. As you complete stages, you also unlock support characters, each of which enhances your character by enabling him to regenerate life or deal more damage.

Along with things you can unlock by playing the game, The Rhythm of Fighters offers extra content, support characters, and playable characters as in-app purchases. Packs of four songs cost $2.99, packs with three support characters cost $0.99 apiece, and new playable characters cost $2.99 each.

The Rhythm of Fighters is an interesting experiment. By itself, it’s a fun rhythm game (despite the frustrating bugs), and a must-have for anyone who loves The King of Fighters series. But as a fighting game hybrid, it could be so much more than a knockoff of Elite Beat Agents. Despite that, it’s a fun distraction for 99 cents.

TidBITS Watchlist: Notable Software Updates for 21 July 2014

DEVONagent Lite, Express, and Pro 3.8.1 — DEVONtechnologies has updated all three editions of its DEVONagent research software (Lite, Express, and Pro) to version 3.8.1. The Pro and Express editions now support Open Graph for matching HTML pages, enable you to skip Amazon search results while crawling, improve the reliability of the Twitter Accounts scanner, fix an incompatibility with DEVONthink 2.7.6 that caused delays, and improve the handling of background tasks. The Pro edition now executes many scripts in the background, adds a German localization, ensures the address bar is properly

updated, and fixes support for RSS feeds using isPermaLink=false. All three editions also receive an update to the MacUpdate plug-in. (All updates are free. DEVONagent Lite, free, release notes; DEVONagent Express, $4.95 new, release notes; DEVONagent Pro, $49.95 new with a 25 percent discount for TidBITS members, release notes. 10.6.8+)

Read/post comments about DEVONagent Lite, Express, and Pro 3.8.1.

Typinator 6.1 — Following its jump to version 6.0 (see “Typinator 6.0,” 17 June 2014), Ergonis has released Typinator 6.1 with a number of enhancements added to the text expansion tool. The update brings new markers that can temporarily pause Typinator for suppressing the next replacement, as well as for suppressing the current replacement (used for defining exceptions of other rules). It also adds a new set for defining exceptions for the auto-capitalize sentences rule, a function for sorting text lines (such as for sorting lines found in the clipboard), and an

option to insert a delay in the middle of an expansion. In addition, Typinator 6.1 fixes an issue where some regular expressions matched internally used mark characters, a memory leak that occurred when set options were edited multiple times, and a problem that caused auto-capitalization of sentences to fail in certain cases. (€24.99 new with a 25 percent discount for TidBITS members, 7.2 MB, release notes, 10.5.8+)

Read/post comments about Typinator 6.1.

PDFpen and PDFpenPro 6.3.1 — Smile has released version 6.3.1 of PDFpen and PDFpenPro, a small maintenance release to the company’s all-purpose PDF editing apps that fixes the frustration of a few bugs. The update works around a performance issue caused by a bug in OS X 10.9 Mavericks, fixes a crash that occurred when hot-plugging a scanner, avoids potential crashes with the scanning window, and improves the appearance of the editing bar when running the OS X Yosemite developer preview. ($59.95/$99.95 new with a 20 percent discount for TidBITS members, free updates, 52.0/52.8 MB, release notes, 10.7+)

Read/post comments about PDFpen and PDFpenPro 6.3.1.

Voila 3.8 — Global Delight has released Voila 3.8 with several new features added to the screen capture utility. The update adds a magnifier to aid in drawing precise boundaries for your captures, brings support for uploading captures directly to Google Drive, adds support for scaling down videos recorded on a Retina display, and improves access to trimming videos by placing an option in the video player strip. For a limited time, Voila is priced at $14.99, 50 percent off its normal $29.99 price. ($29.99 new from Global Delight with a 25 percent discount for TidBITS

members or from the Mac App Store, free update, 23.5 MB, 10.8+)

Read/post comments about Voila 3.8.

ExtraBITS for 21 July 2014

Managing Editor Josh Centers sat down with Gene Steinberg to discuss Gmail and Apple TV on The Tech Night Owl podcast, Apple has been denied a trademark on its Touch ID fingerprint scanner, and Greenpeace has declared Apple the greenest company in the tech world.

Josh Centers Discusses Gmail and Apple TV on The Tech Night Owl — TidBITS Managing Editor Josh Centers joined host Gene Steinberg on The Tech Night Owl podcast to explain why he uses Gmail, and what Apple will need to do to keep the Apple TV competitive.

Apple Denied Touch ID Trademark — The U.S. Patent and Trademark Office has denied Apple’s application to trademark Touch ID, the fingerprint-sensing technology built into the iPhone 5s. Apparently, the Touch ID name is too similar to an existing trademark, Kronos Touch ID, which the USPTO claims could cause customer confusion. Apple has six months to change the trademark or make a deal with Kronos, a workforce management solution company whose biometric Touch ID terminal manages employee time-tracking and access in casinos.

Apple Declared the Greenest Company in Tech — Apple is now the greenest major tech company, according to a new report by Greenpeace. In the organization’s Clean Energy Index, which ranks companies based on clean energy usage, as well as use of other energy sources such as natural gas, coal, and nuclear, Apple scored 100 percent. By comparison, Facebook received 49 percent, Google scored 48 percent, and Amazon Web Services managed only a paltry 15 percent.