#1528: The Case of the Top Secret iPod, Apple’s 2020 Environmental Progress Report, your thoughts on the App Store

In last week’s issue, we documented the many developer complaints against the App Store and asked you to share your thoughts in a survey. Several hundred readers responded with strong opinions about how Apple should change the App Store. But while we’ll criticize Apple in areas where the company could do better, we’ll also praise it for work well done. Apple recently released its 99-page 2020 Environmental Progress Report, and Adam Engst has now read the entire thing, both so he can share key points and encourage anyone interested in the environment to see how much the company has accomplished. Finally, Apple veteran David Shayer joins us again with the gripping story of his work on a top-secret government iPod modification, an article that went viral, garnering coverage on Ars Technica, BBC, CNN, Popular Mechanics, The Verge, and many other outlets. Notable Mac app releases this week include CleanMyMac X 4.6.11 and Transmit 5.6.6.

Your Thoughts on the App Store: Apple Should Change, but Voluntarily

In “Developers v. Apple: Outlining Complaints about the App Store” (13 August 2020), we outlined the major developer complaints about the App Store: Apple’s 30% revenue cut, Apple picking winners and losers, App Store ads, counterfeit apps, unfair developer treatment, capricious and arbitrary rules, banning game-streaming services, and the devaluation of apps.

We also wanted to get your opinions on how Apple is running the App Store and treating developers. It turns out that, although TidBITS readers are largely critical of how Apple runs the App Store, they’re also against government regulation as a solution. Let’s dig into the survey questions and your responses.

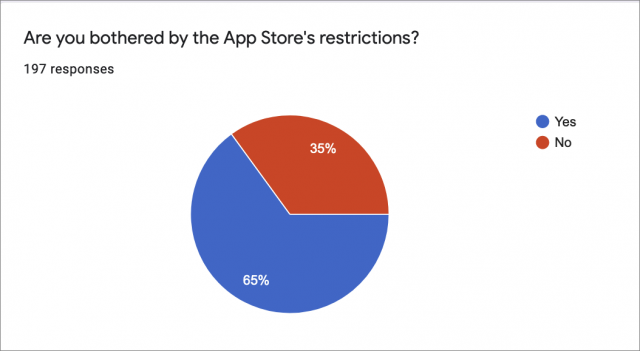

Are you bothered by the App Store’s restrictions?

We asked an admittedly broad question: Are you bothered by the App Store’s restrictions? That could include any number of issues we outlined, such as prohibitions on certain types of apps, removing apps Apple finds objectionable, etc. Apple is unapologetic about this, claiming that the restrictions are in place to protect its users and maintain high quality.

So we were a bit surprised by the strong response from our readers: a whopping 65% of TidBITS readers said they were bothered by App Store restrictions, with only 35% unbothered.

This was especially interesting, given that our audience tends to lean older and toward cautious usage patterns, and Apple is being too restrictive even for them. Maybe it’s time for Apple to ease up a bit.

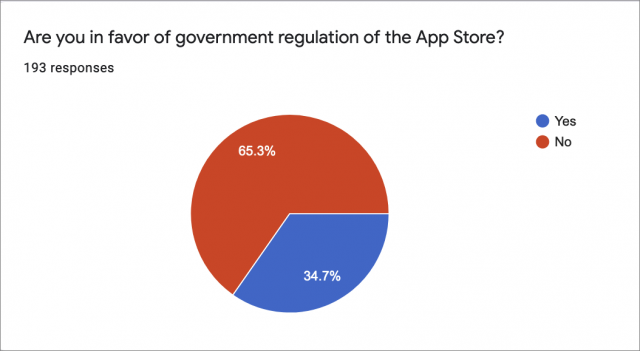

Are you in favor of government regulation of the App Store?

Yet another overwhelming response: No. In fact, at 65% against and 35% for, the numbers are almost identical to the responses about App Store restrictions. TidBITS readers may find the App Store to be too restrictive, but they don’t want the government stepping in and dictating how Apple should run it.

We share that concern. While regulators may mean well, government officials are often uninformed and confused. The most comprehensive plan proposed so far, at least as it relates to Apple, is from Senator Elizabeth Warren (D-MA), who wants to break the App Store away from Apple.

Not only would this not solve the main issues people have, but it would also create chaos. How would it even work for another company to run the App Store? Would Apple have to allow old-fashioned software installs by default and then point people to third-party app stores? Would there be any reason for developers to use an App Store that wasn’t integrated into the entire user experience? We have no idea. Many people oppose sideloading (more on that in a moment), but making the App Store independent of Apple would take those concerns to a whole other level.

For the most part, developers aren’t upset about having to compete with iWork, News, Weather, and other Apple apps. They give users reasonable defaults, and third-parties can usually offer more-capable products. For some reason, likely ignorance, congressional representatives keep circling back to this issue, such as Representative Val Demings (D-FL), who spent much of her time with Tim Cook asking about competitors to Screen Time, a feature from which Apple derives no revenue (see “A Quick Rundown of Big Tech’s Showdown with Congress,” 31 July 2020).

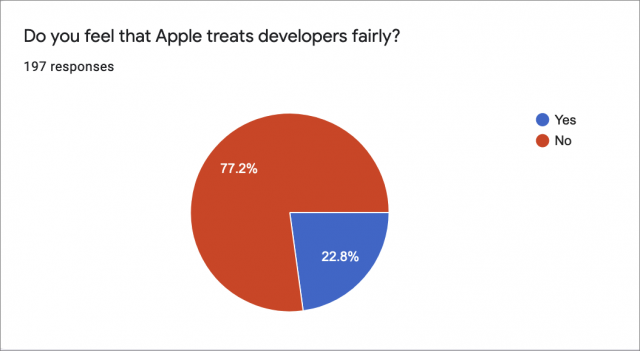

Do you feel that Apple treats developers fairly?

The answer is No, by an overwhelming margin of 77% to 23%. This didn’t come as a surprise, since it’s well-known that Apple treats larger developers differently than small ones. We documented several examples in “Developers v. Apple: Outlining Complaints about the App Store.”

However, we have to give Apple some credit here. After Epic Games slipped in a way to buy in-app purchases in Fortnite without using Apple’s payment system, Apple not only banned the Fortnite app from the App Store, it is now threatening to terminate Epic’s developer account entirely. Apple has often taken such a heavy-handed approach with small developers, but seldom with a developer as large as Epic.

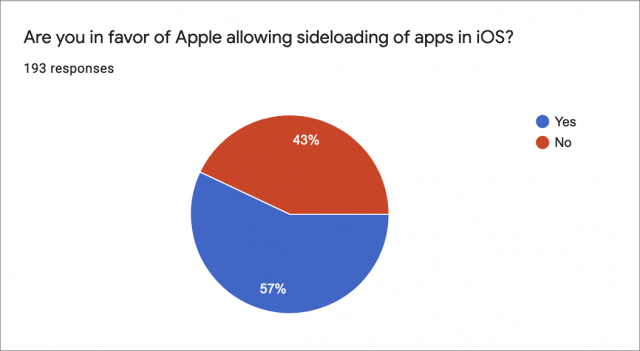

Are you in favor of Apple allowing sideloading of apps in iOS?

The answers to this question shocked me: 57% of you support it, a double-digit margin. Sideloading is controversial because it could open a vector for malware, the confusion of apps distributed outside of the App Store, and other issues. So I was surprised to see so many TidBITS readers supporting the idea.

But as I pointed out in “Developers v. Apple: Outlining Complaints about the App Store,” Apple allows “sideloading” on the Mac without many malware issues, thanks to strong security features and app signing, the latter of which will be required for all apps running on Apple silicon Macs.

In theory, allowing sideloading would let developers sidestep all of the App Store complaints. Apple could simply say: “Don’t like the App Store rules? Distribute your app on your own.”

It’s a nice theory, anyway. One of the bizarre twists in the recent Epic Games versus Apple drama is that while Epic sued Apple, demanding that Apple allow Epic to sideload its games in iOS, Epic also sued Google, which already allows sideloading on Android. Apparently, Epic didn’t think sideloading worked sufficiently well to stick with it instead of putting Fortnite in the Google Play Store.

Apple has since submitted emails between itself and Epic Games as evidence, which shed some light on the situation. Here’s what Epic really wants: to have its own store, which shares no revenue with Apple, and for Apple to distribute that independent store in the App Store.

That’s bonkers. If Apple acquiesced to that demand or was forced to, app discovery and acquisition would become complete chaos, as every developer would scramble to create its own App Store or join cheaper ones.

Surely Epic Games understands how destructive this is. Imagine if Valve, a gaming company that distributes software through its Steam service, sued to force Epic to publish Steam in the Epic Games Store, without the usual 12% cut to Epic. Epic CEO Tim Sweeney would laugh himself out of his chair, but that’s exactly what Epic is asking of Apple and Google, and only Apple and Google, because Epic isn’t going after Microsoft or Sony, which have very similar terms on their game consoles. In context, it’s hard to see Epic’s “request” as some sort of fight for freedom or a business move, but rather an attempt to sabotage smartphone app stores.

There’s no making some people happy, and it’s possible that Apple allowing sideloading might not be the solution I thought it would be.

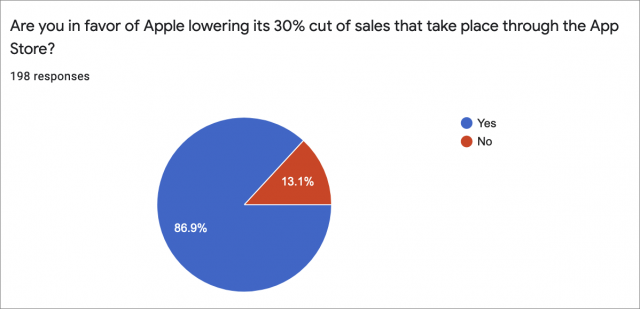

Are you in favor of Apple lowering its 30% cut of sales that take place through the App Store?

The answers here were less surprising: you overwhelmingly think Apple should lower the 30% cut it takes from most App Store transactions. Nearly 87% of you voted in favor of Apple reducing the 30%.

Granted, we don’t have the data Apple does, but most people seem to think the 30% cut is too high. If or how that gets resolved is up to Apple and regulators. And, if nothing else, it’s bad PR for Apple when such a large percentage of the company’s customers feel that it’s overcharging.

Some people have postulated that Apple could actually bring in more money by reducing the take for certain kinds of products that are currently kept outside the App Store entirely. For instance, what if Apple allowed Amazon to sell Kindle books in its iOS app for a mere 1% of the sale price? Amazon might be amenable to using in-app purchases (which isn’t true now), and Apple would have a new source of income. Similarly, in exchange for dropping the base rate well below 30%, Apple could extract a 1% tax on sales of real-world products and services, which are currently entirely free. Might that be fairer?

Of course, this poll is small and far from scientific, and Apple has no obligation to pay attention to the results, much less base business decisions on them. However, it does give us a bit of insight into how TidBITS readers are thinking about the App Store. Thanks to everyone who responded!

Read Apple’s 2020 Environmental Progress Report

A few weeks ago, Apple released its 2020 Environmental Progress Report. It’s a masterpiece of communications, starting with a gorgeous website with progressively revealed high-level content as you scroll. More About buttons provide additional details on the site, but the mother lode is a 99-page PDF. I’d encourage anyone with more than a passing interest in environmental issues to read the full PDF because it’s impressive to see just how much time and money Apple is putting into its environmental efforts. We think of Apple as a technology company, but it’s doing more than many organizations that focus exclusively on the environment.

Apple’s Environmental Progress So Far

Most notably, of course, Apple’s stores, data centers, and offices in 44 countries are powered with 100% renewable energy, much of it generated by Apple-driven solar, wind, hydro, and biogas installations. Even better, over 70 of Apple’s suppliers have committed to using only renewable energy for producing Apple products. As of April 2020, Apple is carbon neutral for its corporate emissions, thanks to investments in projects that protect and restore forests, grasslands, and wetlands.

But it doesn’t stop there. In the past 11 years, Apple has reduced the average energy use of its products by 73%, to the point where the company estimates that it costs only $0.70 per year to charge an iPhone 11 Pro once per day. Apple is also working hard to reduce its use of virgin materials that come with significant environmental impacts. For instance, the Taptic Engine in the iPhone 11 models uses 100% recycled rare earth elements, a first for any smartphone, and the 2019 MacBook Air has 40% recycled materials overall.

Apple has also reduced its use of plastics in packaging by 58% over the past 4 years, and all of the paper used in packaging comes either from recycled sources or responsibly managed forests. Through partnerships with The Conservation Fund and the World Wildlife Fund, Apple says it has improved the management of more than 1 million acres of working forests in the United States and China.

Apple’s Environmental Goals

As impressive as these achievements are, they pale in comparison with the company’s larger goals:

- By 2030, Apple wants to be carbon neutral across its entire footprint, meaning that it will take into account the carbon impact of the entire lifecycle of its products. That will require low-carbon designs, increased energy efficiency, transitioning its supply chain to 100% renewable energy, avoiding direct carbon emissions, and scaling up investments in carbon removal projects.

- Apple wants to work toward using only recycled and renewable materials in both products and packaging. There’s no time frame on that ambitious goal, but the company does say that it’s trying to eliminate all plastics in packaging by 2025.

The more I read through Apple’s Environmental Progress Report, the more astonished I became. I think it’s safe to say that I pay more attention to Apple than most people, and while I’ve seen Apple’s press releases on a solar farm here or reduced use of toxic materials there, I had never fully internalized just how much Apple does with the environment in mind. The report is definitely worth your time.

Apple’s Environments of Scale

My first thought was that Apple must be spending billions on these efforts. As far as I can tell from the Environmental Progress Report and Apple’s financial filings, the company never says exactly how much. However, it does trumpet the fact that it has issued $4.7 billion in “green bonds,” which are fixed-income investments whose proceeds must go to specific environmental projects. Apple also claims that it is the largest corporate issuer of green bonds, though I’m not financially savvy enough to know why it would want to issue bonds rather than financing environmental efforts directly.

I suspect that Apple can do all this for the environment in large part because it makes so much money. Scale is important here—when we were running Take Control Books, we donated $0.25 per print-on-demand copy sold to a charity that planted trees. I don’t remember the total amount we ended up donating, but it was a drop in the ocean compared to what Apple is doing.

Reading about Apple’s environmental achievements and goals makes me feel better about Apple’s traditionally high prices. We all have different thresholds, I’m sure, for how much more we’re willing to pay to ensure that a manufacturer isn’t engaging in horrible behaviors like forced child labor or egregious pollution. With Apple, it’s clear that some percentage of the purchase price goes to deeply considered and carefully analyzed reductions in environmental impact. I’m willing to make that tradeoff for devices that I use all day, every day.

Of course, Apple has multiple motivations for its environmental efforts. Apple is a for-profit company, so if building a massive solar farm to power a data center results in long-term reduced energy costs along with the boost toward the effort to be carbon neutral, that’s a double win. Similarly, you may have noticed that the boxes that many Macs come in are smaller than they used to be—Apple has reduced the amount of packaging necessary to protect them in shipping. That’s good for the environment, particularly with reduced plastics, but it also means that more units fit in a shipping container, which reduces Apple’s transportation costs (and also its carbon emissions from shipping). And while Apple has numerous environmental projects that benefit the communities that host Apple data centers, those may be accompanied by tax breaks and generalized goodwill.

It’s easy to be cynical and suggest that Apple’s doing some of these things only because it saves money. But that’s missing the point—the best ways to protect the environment, the ones that we want all companies to be doing, are those that are both environmentally positive and improve the bottom line.

Some years ago, there was a lot of coverage about how Walmart played hardball with its suppliers, forcing them to accept razor-thin margins to be able to sell their products to Walmart. It’s now clear that Apple is using similar corporate pressure on its suppliers to get them to agree to commit to clean energy, waste reduction, and lowered greenhouse gas emissions. Is Apple throwing its weight around? Yes, just as Walmart was (and continues to do), but with a greater good in mind, rather than just shaving a few pennies off already cheaply made products.

Apple CEO Tim Cook has said:

Climate change is real and we all share a responsibility to fight it. We will never waver, because we know that future generations depend on us.

In many ways, climate change is just like today’s coronavirus crisis. It’s a global threat that ignores borders, kills people, and destroys economies. The difference is that climate change moves slowly, so its mortality and economic effects add up gradually over decades rather than overwhelming us in a period of months. But there won’t be quick fixes, either—there’s no vaccine for climate change. Bill Gates lays this out well in a recent GatesNotes post called “COVID-19 is awful. Climate change could be worse.”

Even Apple’s efforts are unlikely to make a significant dent in the climate change problem—it’s just too vast—but I hope they can serve as a role model, both for other large businesses and for governments that seem to lack the willpower to move in the necessary direction.

The Case of the Top Secret iPod

It was a gray day in late 2005. I was sitting at my desk, writing code for the next year’s iPod. Without knocking, the director of iPod Software—my boss’s boss—abruptly entered and closed the door behind him. He cut to the chase. “I have a special assignment for you. Your boss doesn’t know about it. You’ll help two engineers from the US Department of Energy build a special iPod. Report only to me.”

The next day, the receptionist called to tell me that two men were waiting in the lobby. I went downstairs to meet Paul and Matthew, the engineers who would actually build this custom iPod. I’d love to say they wore dark glasses and trench coats and were glancing in window reflections to make sure they hadn’t been tailed, but they were perfectly normal thirty-something engineers. I signed them in, and we went to a conference room to talk.

They didn’t actually work for the Department of Energy; they worked for a division of Bechtel, a large US defense contractor to the Department of Energy. They wanted to add some custom hardware to an iPod and record data from this custom hardware to the iPod’s disk in a way that couldn’t be easily detected. But it still had to look and work like a normal iPod.

They’d do all the work. My job was to provide any help they needed from Apple.

I learned that an official at the Department of Energy had contacted Apple’s senior vice president of Hardware, requesting the company’s help in making custom modified iPods. The senior VP passed the request down to the vice president of the iPod Division, who delegated it to the director of iPod Software, who came to see me. My boss was told I was working on a special project and not to ask questions.

Background

I was the second software engineer hired for the iPod project when it started in 2001. Apple Marketing hadn’t yet come up with the name iPod; the product was known by the code name P68. The first software engineer later became the director of iPod Software, the guy who gave me this special assignment. I wrote the iPod’s file system and later the SQLite database that tracked all the songs. Over time, I worked on almost every part of the iPod software, except the audio codecs that converted MP3 and AAC files into audio.

(Those audio codecs were written by two engineers with advanced degrees from Berkeley and Stanford. When they weren’t teasing each other about which school was better, they were writing mathematical audio code that I was scared to touch. You would no more let a regular engineer mess with code like that than you’d let a bike mechanic rebuild the transmission in a Porsche. They had an occasional poker game I played in. The only reason I didn’t lose all my money was that one of them enjoyed his vodka.)

Compiling the iPod operating system from source code, loading it onto an iPod, and testing and debugging it was a fairly complex process. When a new engineer started, we typically gave them a week to learn all this before we assigned them any actual tasks.

The iPod operating system wasn’t based on another Apple operating system like Classic Mac OS or Darwin, the underlying Unix core of macOS, iOS, iPadOS, watchOS, and tvOS. The original iPod hardware was based on a reference platform Apple bought from a company called Portal Player. Portal Player had also provided the lower levels of the iPod OS, including power management, disk drivers, and the realtime kernel (which Portal Player had licensed from another company called Quadros). Apple bought the higher levels of the iPod OS from Pixo, a company started a few years earlier by ex-Apple engineers trying to write a general-purpose cell phone operating system to sell to mobile phone companies like Nokia and Ericsson. Pixo code handled the user interface, Unicode text handling (important for localization), memory management, and event processing. Of course, Apple engineers modified all this code, and over time, rewrote much of it.

iPod OS was written in C++. Since it didn’t support third-party apps, there was no external documentation on how it worked.

Finally, the iPod team developed on Windows computers. Apple didn’t have working ARM developer tools yet, because this was before the iPhone shipped. The iPod team used ARM developer tools from ARM Ltd., which ran only on Windows and Linux.

My job was to get Paul and Matthew up and running on a new operating system they’d never seen before, much less developed for.

Getting Started

I requisitioned an empty office for Paul and Matthew in our building. I had IS&T (Apple’s IT department) reroute the Ethernet drops in that office so they connected only to the public Internet, outside Apple’s firewall, preventing them from accessing Apple’s internal network. Apple’s Wi-Fi network always connects outside the firewall. Even inside Apple buildings, if you’re using Wi-Fi, you need a VPN to get past Apple’s firewall. This wasn’t a collaboration with Bechtel with a contract and payment; it was Apple doing a favor under the table for the Department of Energy. But access for that favor went only so far.

Needless to say, Paul and Matthew weren’t allowed to access our source code server directly. Instead, I gave them a copy of the current source code on a DVD and explained it couldn’t leave the building. Ultimately, they were allowed to keep the modified copy of the iPod OS they built, but not the source code for it.

Apple didn’t provide them any hardware or software tools. I gave them the specs for the Windows computers they needed, along with the ARM compiler and JTAG debugger. They bought retail iPods to work on, several dozen at least, possibly many more.

As with all Apple buildings, everyone had to present an Apple badge to the badge reader to unlock the door and enter the iPod building. Only employees cleared for our building were allowed in. On each floor, there was another locked door and badge reader, and only people cleared for that floor were allowed in.

So every day, Paul and Matthew called me from the lobby since they didn’t have Apple badges. I signed them in as guests and escorted them to their office. Eventually, I arranged to get them vendor badges, as if they were selling Apple coffee or memory chips, so I didn’t have to sign them in daily. I was a programmer, not a babysitter.

Top Men

Paul and Matthew were smart—top men, even—and with a little help, they were up and running pretty quickly. I showed them how to set up the development tools, build a copy of the operating system from source, and load it into the iPod. We made some temporary changes to the user interface, so we could see that their build was actually running. I showed them how to use the JTAG hardware debugger, which was rather finicky. They dove into their work.

As they learned their way around the system, they explained what they wanted to do, at least in broad strokes. They had added special hardware to the iPod, which generated data they wanted to record secretly. They were careful to make sure I never saw the hardware, and I never did.

We discussed the best way to hide the data they recorded. As a disk engineer, I suggested they make another partition on the disk to store their data. That way, even if someone plugged the modified iPod into a Mac or PC, iTunes would treat it as a normal iPod, and it would look like a normal iPod in the Mac Finder or Windows Explorer. They liked that, and a hidden partition it was.

Next, they wanted a simple way to start and stop recording. We picked the deepest preferences menu path and added an innocuous-sounding menu to the end. I helped them hook this up inside the code, which was rather non-obvious. In all other respects, the device functioned as a normal iPod.

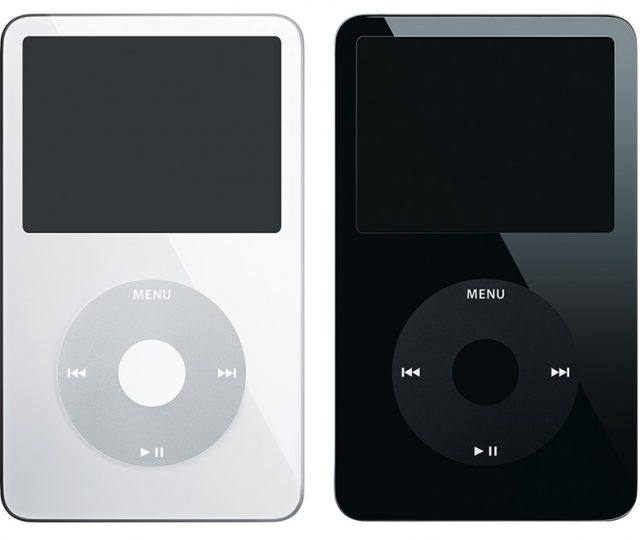

At the time, the latest iPod was the fifth-generation iPod, better known as the “iPod with video.” It was relatively easy to pop open the case and close it again without leaving obvious marks, unlike the iPod nano models that became popular shortly after. Plus, the fifth-generation iPod had a 60 GB disk, so there was plenty of room to have lots of songs and still record extra data. And it was the last iPod for which Apple didn’t digitally sign the operating system.

That was important because it made the fifth-generation iPod somewhat hackable. Hobbyists enjoyed getting Linux to run on iPods, which was hard to do without the special knowledge and tools Apple possessed. We on the iPod engineering team were impressed. But Apple corporate didn’t like it. Starting with the iPod nano, the operating system was signed with a digital signature to block the Linux hackers (and others). The boot ROM checked the digital signature before loading the operating system; if it didn’t match, it wouldn’t boot.

That was important because it made the fifth-generation iPod somewhat hackable. Hobbyists enjoyed getting Linux to run on iPods, which was hard to do without the special knowledge and tools Apple possessed. We on the iPod engineering team were impressed. But Apple corporate didn’t like it. Starting with the iPod nano, the operating system was signed with a digital signature to block the Linux hackers (and others). The boot ROM checked the digital signature before loading the operating system; if it didn’t match, it wouldn’t boot.

I don’t think Paul and Matthew ever asked Apple about signing their custom operating system build so it would run on the iPod nano. I’m pretty sure Apple would have refused. The larger fifth-generation iPod was better suited to their purposes anyway.

After a few months of on-again, off-again work in their requisitioned office, Paul and Matthew finished integrating their custom hardware into the iPod and wrapped up the project. They moved their computers and debugging hardware back to Bechtel’s office in Santa Barbara. They returned the latest DVD with Apple source code to me, along with their Apple vendor badges. They said goodbye, and I never saw them again. The DVD sat on a shelf in my office for years, until I finally tossed it while cleaning up.

What Were They Doing?

The Department of Energy is huge. Its 2005 budget was $24.3 billion. It’s responsible for the US nuclear weapons and nuclear power programs, including the Los Alamos National Laboratory, which was part of the Manhattan Project. As the DOE’s budget request says:

The FY 2005 budget proposes $9.0 billion to meet defense-related objectives. The budget request maintains commitments to the nuclear deterrence requirements of the Administration’s Nuclear Posture Review and continues to fund an aggressive strategy to mitigate the threat of weapons of mass destruction.

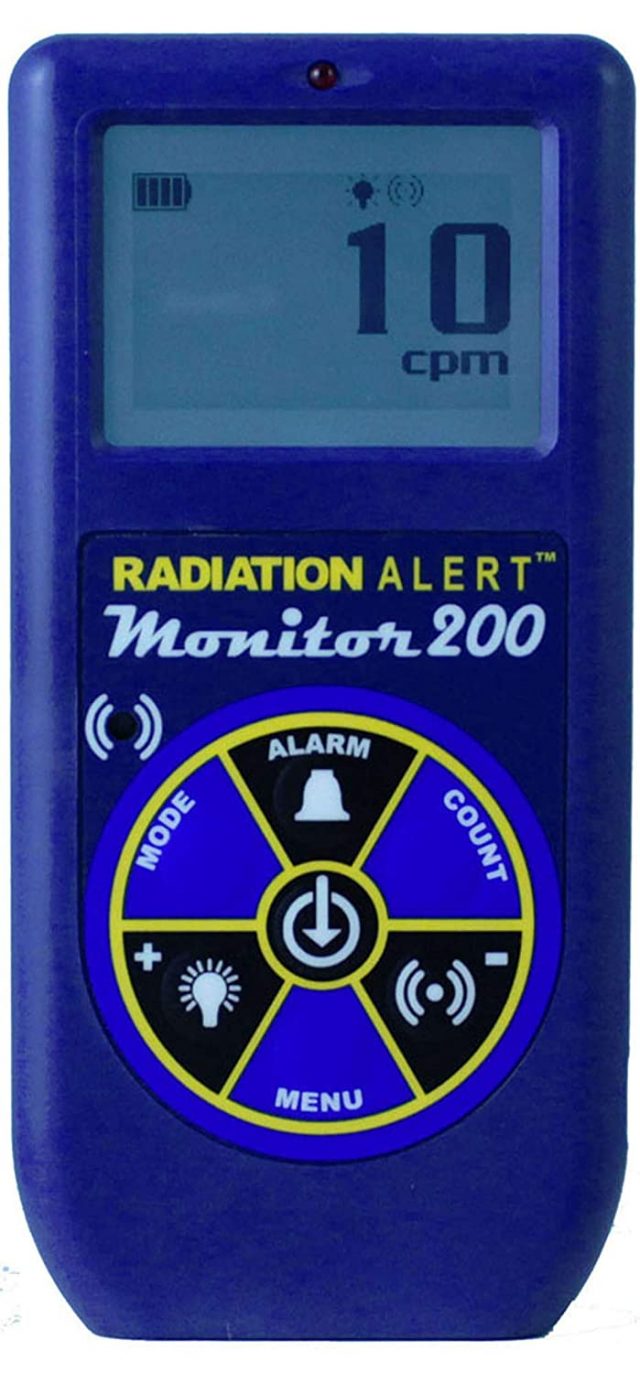

My guess is that Paul and Matthew were building something like a stealth Geiger counter. Something that DOE agents could use without furtively hiding it. Something that looked innocuous, that played music, and functioned exactly like a normal iPod. You could walk around a city, casually listening to your tunes, while recording evidence of radioactivity—scanning for smuggled or stolen uranium, for instance, or evidence of a dirty bomb development program—with no chance that the press or public would get wind of what was happening. Like all other electronic gadgets, Geiger counters have gotten smaller and cheaper, and I was amused to run across the Radiation Alert Monitor 200, which looks an awful lot like a classic iPod.

My guess is that Paul and Matthew were building something like a stealth Geiger counter. Something that DOE agents could use without furtively hiding it. Something that looked innocuous, that played music, and functioned exactly like a normal iPod. You could walk around a city, casually listening to your tunes, while recording evidence of radioactivity—scanning for smuggled or stolen uranium, for instance, or evidence of a dirty bomb development program—with no chance that the press or public would get wind of what was happening. Like all other electronic gadgets, Geiger counters have gotten smaller and cheaper, and I was amused to run across the Radiation Alert Monitor 200, which looks an awful lot like a classic iPod.

Whenever I asked Paul and Matthew what they were building, they changed the subject and started arguing about where to go for lunch. Standard geeks.

The Custom iPod That Never Existed

Only four people at Apple knew about this secret project. Me, the director of iPod Software, the vice president of the iPod Division, and the senior vice president of Hardware. None of us still work at Apple. There was no paper trail. All communication was in person.

If you asked Apple about the custom iPod project and got past the stock “No comment,” the PR people would tell you honestly that Apple has no record of any such project.

But now you know.