#1714: Generative AI Web scraping, persistent task reminders with Due, Authy breach

Generative AI features prominently in this issue. First, Adam Engst links to his Command Control Power podcast discussion that segued from Apple Intelligence to deeper questions surrounding AI. Then, to provide an alternative perspective to the outrage that seems to be sweeping the tech publishing world, he explains why he’s not particularly perturbed by AI companies scraping the open Web to train large language and image diffusion models. Back in the Apple world, he examines Due, an iPhone and Mac app that provides persistent notifications that ensure you can’t miss a reminder. Finally, we share the news that a hacker stole phone numbers from 33 million users of the two-factor authentication service Authy. Notable Mac app releases this week include Arc 1.49, Cyberduck 9.0, and SpamSieve 3.0.5.

Exploring Generative AI on the Command Control Power Podcast

My writing about generative AI (see “How to Identify Good Uses for Generative AI Chatbots and Artbots,” 27 May 2024) and Apple’s announcement of Apple Intelligence (see “Examining Apple Intelligence,” 17 June 2024) triggered several podcast appearances for me. Command Control Power typically focuses on issues of interest to Apple consultants, but this 90-minute conversation with hosts Joe Saponare and Jerry Zigmont delved into some of the deeper questions surrounding generative AI. You can also watch the live stream on YouTube.

Along with some discussion of Apple Intelligence, we talked about making effective use of generative AI, why we probably won’t end up with AI assistants talking to each other for a while yet, what sort of jobs aren’t at risk of being replaced by AI, and how we can deal with AI slop at both the individual and societal levels.

Although we recorded the episode a few weeks ago, it just dropped today, so I took advantage of a long ElliptiGO ride to refresh my memory of what we discussed. Perhaps I just like hearing myself talk, but I thought the wide-ranging conversation touched on important yet subtle topics. Give it a listen, and let me know what you think in the comments.

Just Due It: Persistent Notifications for Tasks

I hate it when I miss things I’m supposed to do. Although I have a good memory, I can forget things and miss notifications due to being either distracted or too focused. That was part of why I wrote “A Call to Alarms: Why We Need Persistent Calendar and Reminder Notifications” (11 May 2023) and started using In Your Face (see “In Your Face Provides Persistent Notifications for Events and Tasks,” 26 June 2024).

Helpful though In Your Face is, it suffers from one major problem—it runs only on the Mac, and I’m not always at my Mac. In contrast, my iPhone is nearly always in my pocket, and when it’s not, my Apple Watch is on my wrist. Is there an iPhone app that would provide persistent notifications I can’t ignore?

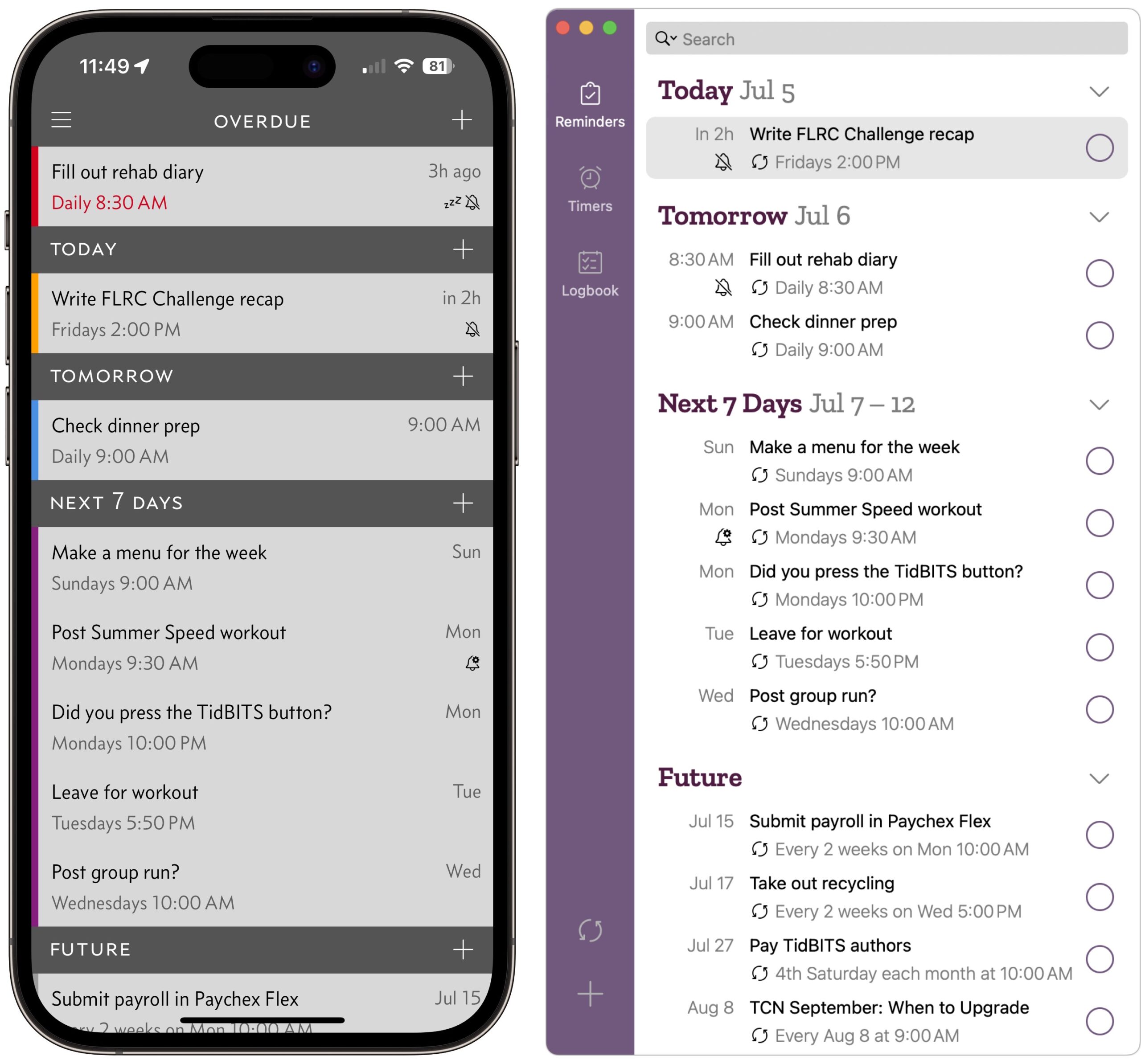

In the comments on my original article, numerous people recommended Lin Junjie’s reminder and timer app Due, which offers iPhone ($7.99) and Mac ($14.99) apps. The iPhone purchase includes iPad and Apple Watch apps; the Mac app is also available via Setapp. The iPhone and Mac apps seem functionally identical and sync data via iCloud, so you could create and manage reminders on the Mac while receiving notifications on the iPhone and Apple Watch. But the iPhone app can stand entirely on its own, and I prefer it. Purchasing the iPhone version of Due gets you a year of feature updates; receiving future features after that requires a $4.99 per year subscription.

Due’s claim to fame is that it repeatedly notifies you about outstanding tasks until you mark them as done or reschedule them. It’s nearly impossible to ignore Due, and many of its controls revolve around managing its reminder notifications. (I won’t address its timer capabilities—ad hoc access to timers on the Apple Watch via Siri meets my timer needs.)

Due’s main screen lists past, present, and future reminders and provides + buttons for creating new reminders. It supports rudimentary natural language entry, so you can type “Pack first aid kit for workout tomorrow at 5:45 PM,” and you’ll get a reminder set for 5:45 PM tomorrow. Alas, it doesn’t understand natural language repeat options like “every Tuesday at 5:45 PM,” and you must tap to confirm that it understood what you entered.

Since I use Apple’s Reminders heavily, I first opted to import my reminders from there. In its settings, Due lets you import reminders individually, which is more helpful than it sounds because not all reminders benefit from persistent notifications. You can also turn on Auto Import for specified lists in Reminders. And yes, the fact that you can import from Reminders means that Due maintains its own database of tasks, rather than syncing with Reminders.

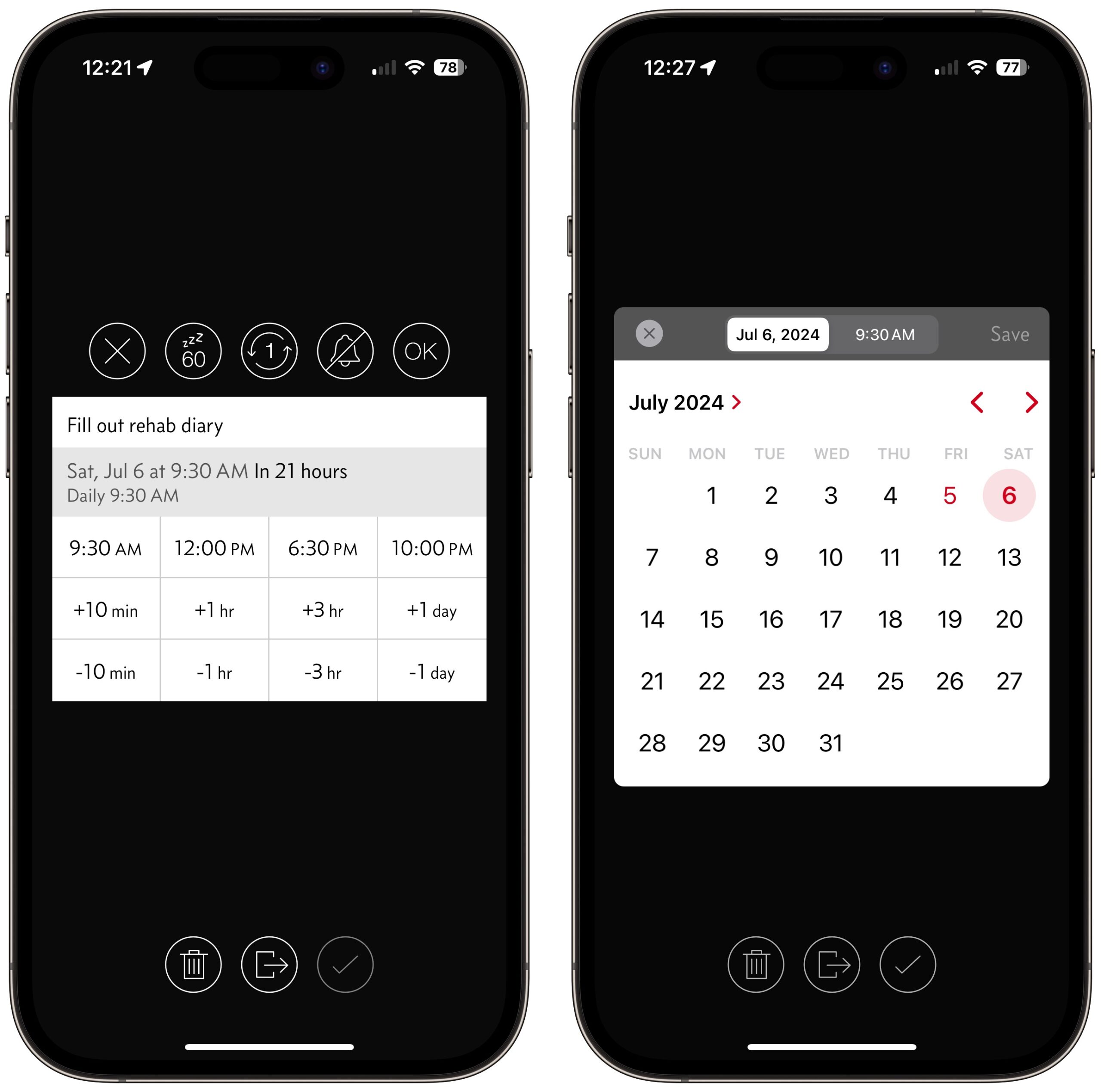

For new reminders, Due presents an interface that might be helpful for those who regularly create reminders, but I find it convoluted. Tapping the gray date-and-time bar (below left) brings up a picker (below right) that requires you to switch between date and time; there seems to be room for both on the same screen. Or you can tap one of the four preset times—9:30 AM, 12 PM, 6:30 PM, and 10 PM—and then adjust that time up or down by tapping the plus or minus buttons below. For instance, you could set a reminder for 11:30 AM by tapping 12 PM and then -10 min three times. Obviously, this is all optional, and Due recommends its natural language parser.

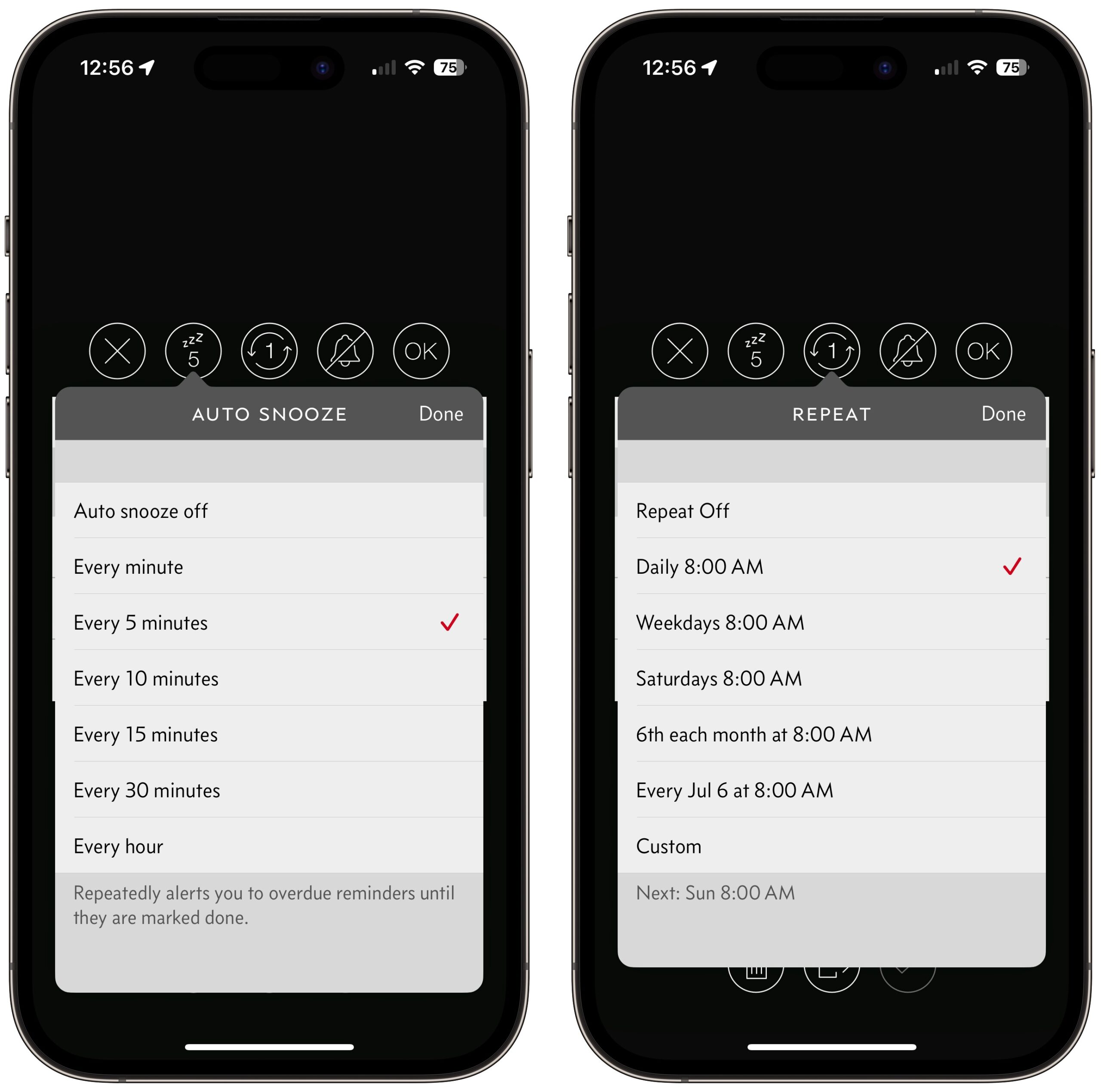

The core of Due comes in setting auto-snooze intervals and repeats. If you have to take some necessary medication every morning at 8 AM, set the auto-snooze to every 5 minutes so you can’t possibly forget for long. I have a few reminders that I set to every 15 minutes, and that’s annoying enough—I set most to hourly because their timing isn’t that important. Due’s custom repeat options are quite flexible; it should be able to handle whatever you need.

In actual usage, Due works as you’d expect. When the clock ticks over to a reminder’s time, Due posts a notification. Ignore it, and Due will keep notifying you on the auto-snooze schedule. Tapping a notification opens the reminder in Due, where you can mark it as done or edit it, but I prefer to touch and hold the notification to bring up quick actions associated with the reminder. Most of the time, I’ve accomplished the task, so I tap Mark Done, but on occasion, I use the +1 hour, +3 hours, and +1 day options to put off future notifications for a while. The Apple Watch notification is similar, with a Mark Done button and buttons to push off future notifications by 1 or 3 hours.

I must admit to some ambivalence regarding Due. It absolutely does what it promises, and if you have tasks that must be completed regularly, particularly those with important timing, Due could be an essential assistant.

However, as much as I use it for a handful of regular reminders, it does not come close to my desired alarm notification type. Issues I have include:

- No calendar events: Due manages reminders, not calendar events, so if you wanted persistent notifications for calendar events, you would have to create separate reminders in Due. That’s more work than I’m willing to take on, especially since Tonya and I rely on shared calendars. It’s also my main problem with Due—it can’t pretend to be an iPhone version of In Your Face.

- Weak Siri integration: Much of the reason I use Apple’s Reminders heavily is because it’s so easy to tell Siri on my Apple Watch, iPhone, or HomePod, “Remind me to pack the car at 6 PM.” Although Due has some Siri support, it has issues on the Apple Watch and runs into trouble because Siri can’t parse the word “Due” well. I tried but couldn’t get Siri to work acceptably. That’s another dealbreaker for me—if it’s too hard to create a reminder, I avoid doing so and try to rely on memory.

- Most reminders don’t need persistent notifications: For most reminders, I like how Reminders notifies me once and leaves the notification on the iPhone’s Lock Screen. I use my iPhone frequently enough that I repeatedly see those notifications until I mark them done. Due has been useful primarily for repeating tasks I can’t delay long—I appreciate how Due nags me every Monday night to make sure I have already published TidBITS. For typical reminders, however, the repeated notifications are just annoying. Once I realized this, I moved some reminders from Due back to Reminders.

While I’ll keep using Due for certain reminders, most of my needs don’t fit well with its capabilities. Your mileage may vary. If you don’t need persistent notifications for calendar events, don’t use Siri to create reminders, and aren’t already a big Reminders user, Due’s persistent notifications can ensure you never forget to do something on your list.

Why AI Web Scraping (Mostly) Doesn’t Bother Me

Within the Apple pundit echo chamber, it seems like everyone is venting about how tech giants and AI startups are using Web crawlers to train their large language and image diffusion models on information sourced from the public Web. Even Applebot is coming under fire because Apple first trained its models for Apple Intelligence and then said that Web publishers could opt out.

John Voorhees and Federico Viticci of MacStories have penned an open letter to the US Congress and European Parliament that encapsulates the outrage, with links to a boatload of supporting articles. If you’re unfamiliar with the topic, you might want to read their piece for context. In short, they consider training AI models on content from the public Web without having requested prior permission to be ethically problematic, and more generally, they worry that the use of these tools will diminish creativity and consolidate “knowledge” in the hands of tech giants.

I can’t say that John and Federico are wrong. They seem to feel threatened, and I’m not one to tell someone that their feelings are invalid. Nor can I confidently say that the future they predict won’t come true. Finally, I don’t mean to pick on them specifically—I’m using their letter merely as a representative of feelings and concerns that are shared by many others in the publishing world.

Nevertheless, speaking as someone with over 34 years of publishing technical content on the Internet—nearly 16,000 TidBITS articles and hundreds of Take Control ebooks—I’m just not that bothered by all this. My overall opinions aren’t usually so divergent from my tech journalism peers, but since no one seems to be acknowledging that there are multiple sides to every issue, I want to explain why I’m largely unperturbed by AI and much of the hand-wringing that seems to permeate coverage of the field.

I publish to enrich the world, not to make money

Much of the concern seems to center around the belief that AI will prevent writers and artists from making money. I don’t believe that’s necessarily true, and even if it is, it’s not as though the Internet hasn’t caused multiple disruptions to business models in the past.

Regardless, I don’t share this concern because I publish TidBITS to help people understand and make the most of their technological surroundings, not primarily to make money. That has always been true—we published TidBITS for over two years before pioneering the first advertising on the Internet in 1992 (see “TidBITS Sponsorship Program,” 20 July 1992). While the income from the TidBITS sponsorship program was welcome, it wasn’t significant for years. It also eventually waned in importance—since 2011, an increasing percentage of our revenues have come from the TidBITS membership program (see “Support TidBITS by Becoming a TidBITS Member,” 12 December 2011), which lets those who benefit from our work support us directly. I don’t see AI chatbots changing that at all.

But TidBITS has an unusual business model. For many other companies, the bottom line is paramount, and reasonably so. I would suggest that they watch for shifts in the ecosystem and be willing to adapt—we’ve had to do that several times in response to competitive and business pressures. Generative AI may be an agent of change for some industries, just as the Internet has been since the early 1990s. Flourishing in the future has long required adaptability.

AI chatbots won’t take over original content

Many people seem to be worried that AI-generated content will “replace or diminish the source material from which it was created,” as the MacStories letter says. It’s unclear to me what would need to happen for this to be true, at least for genuinely original content. When I write about one of my tech experiences, the only place such a story can come from is my head. I fail to see how my creativity would be diminished by what others do.

It’s important to remember that AI chatbots don’t do anything on their own. They produce text only in response to a prompt from a person, so ChatGPT isn’t somehow going to start a newsletter that will compete with TidBITS. A person could do that, and they could use ChatGPT to generate text for their newsletter. But that’s not the fault of generative AI, and it’s not as though I haven’t had to deal with competition from the likes of 9to5Mac, AppleInsider, and MacRumors as they appeared over the years.

Derivative content is valuable mostly in context

Even in TidBITS, most content isn’t entirely original—scoops are few and far between for most publications. Something happens, information becomes known, and I decide if it’s a topic worth sharing. That’s derivative content. But I research everything I write by reading more about the topic and talking to people, and what I learn informs the resulting article. My eventual article may also draw from my personal experience or simply be what I consider a better way of explaining a complex topic. Such content gains value because of how I’ve chosen to relate it, but it’s adding to the discussion, not starting it.

Could someone learn about what I write from other sources? Certainly, and generative AI doesn’t change that. If what you want to learn is widely known by others, numerous websites already contain that information (at varying levels of clarity and accuracy), and searching the Internet will reveal it. Personally, I’m uninterested in playing the SEO game to try to get my version of some article to rank higher in the search results. It will or it won’t, and my experience is that nothing I do will change that in a big way. I’ve focused my business model on serving regular readers, not chasing eyeballs online.

Old content isn’t worth much

Implicit in the complaints about AI crawlers scraping websites is the concern that it will somehow hurt the market for a site’s older content. If you’re the New York Times (which is suing OpenAI), your back content may be extensive enough and historically important enough that it has at least aggregate value.

However, I’ve found that the nearly 16,000 articles in our archive are largely irrelevant from a business perspective. They might attract a few clicks, but too few to make impression-based banner advertising worthwhile. We don’t generate the millions of pageviews necessary to turn the low CPM rates on banner ads into useful amounts of money.

Web publishing requires constantly creating new content—that’s what real people want to read, and while generative AI may make it somewhat quicker to do that, it’s not drastically different from how some websites hire low-paid workers in other countries to churn out unoriginal posts.

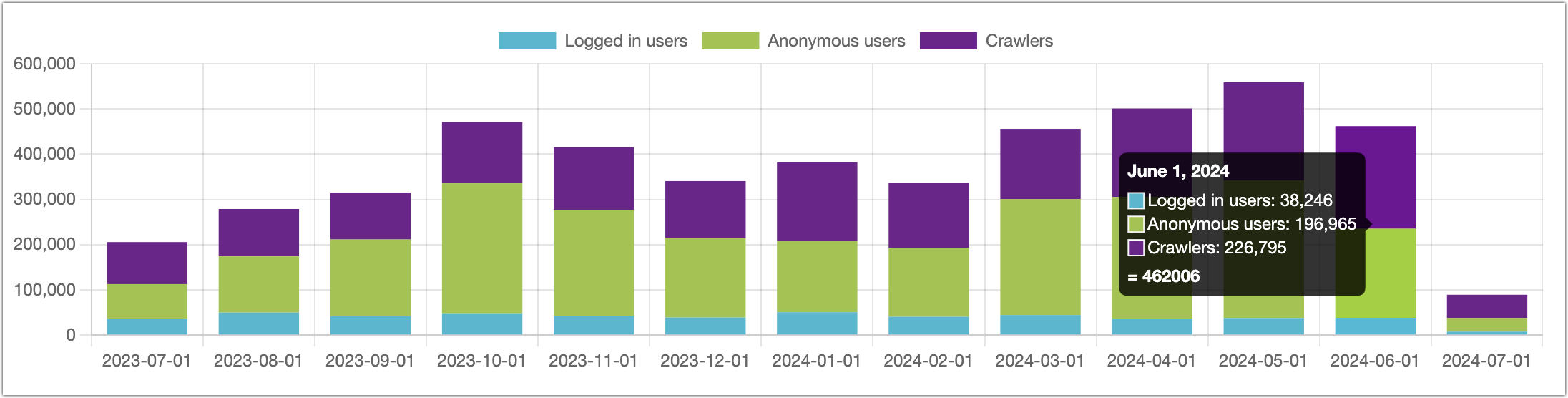

Web scraping doesn’t usually cause operational problems

Crawlers are a fact of life in Web publishing. The Discourse software we use for article comments and TidBITS Talk shows that crawlers generate a quarter to a third of all page views. The extra traffic doesn’t cost us anything or slow down the server because our hosting plan includes sufficient CPU power and more data than we need. That’s not expensive—DigitalOcean charges just $14.40 per month for our Discourse server.

However, small groups with limited hosting plans may be more put out by excessive crawler traffic, regardless of the source. The Finger Lakes Runners Club recently incurred several monthly overage charges with its WPEngine host because of traffic spikes caused by badly behaved AI crawlers. Scraping isn’t the problem; the problem is crawlers that assume every website has infinite processing power and bandwidth. That’s one step below a denial-of-service attack. Such bots—whatever their purpose—should be blocked.

Links and citations aren’t as helpful as we’d like

One of the main complaints about AI chatbots is that clever prompts can cause them to derive their answers heavily from specific sources or even come close to regurgitating text without credit.

I had some fun asking ChatGPT to tell me about The Verge’s coverage of WWDC 2021 because Vox Media owns The Verge, and OpenAI’s licensing agreement with Vox Media requires “brand attribution and audience referrals.” Although ChatGPT was happy to credit The Verge when asked specifically, the links it created never worked for me. When I asked for plain text URLs, I could see that everything in the URL was accurate except the necessary article ID. We’re still in the early days of chatbot attribution capabilities.

On the one hand, I do think that credit is important, and if a chatbot derives significant portions of a response from particular sources, they should be credited and linked, much as the AI-driven search engine Perplexity does. However, the desire to receive credit for one’s work is more about manners than business models. It has also been an issue for years before chatbots.

We’ve published plenty of articles that have generated derivative reporting on numerous other sites. The credit has often been weak at best, with some sites giving TidBITS or the author credit and linking back to the article, but many others doing one or the other but not both, and still others failing to provide credit at all. Regardless, apart from commentary sites like Daring Fireball that encourage readers to read the original article to understand what’s being said (which is also what we do with our ExtraBITS articles), we’ve seen very little referral traffic when other publications link to our original reporting. It’s unsurprising—they’ve essentially rewritten our article, so why would anyone want to read it again?

As a result, I write for those who already read TidBITS, not hypothetical readers who might stumble across one of our articles from a link. The vast majority of such people are one-and-done readers and probably couldn’t say where they visited anyway. That’s a fact, not a criticism—beyond a few big names like Wikipedia and YouTube, I can’t remember all the sites I’ve read while researching this article.

More to the point, I wonder to what extent actual conversations with chatbots return text that should be credited. Just because a chatbot can be prompted to do something undesirable doesn’t mean it’s actually doing so in most situations. It’s legitimate to push the limits on what you can get a chatbot to say, but that’s like probing for security vulnerabilities in other systems. Just because a security researcher can break into a system doesn’t mean everyone can, and just because someone has figured out how to get a particular chatbot conversation to jump the shark doesn’t mean most other conversations stray from the straight and narrow.

It’s called the open Web for a reason

I also have trouble with the suggestion that content intentionally shared on the open Web should require prior permission to use. First, it’s not helpful to complain about something that’s patently impossible—there are 1.9 billion websites out there.

Second, the entire point of publishing on the open Web is to make the content available to everyone. If you want to restrict who can read your content or how they can use it, you put it behind a paywall.

Third, there are already numerous ways content can be repurposed on the open Web without permission, including quoting and linking. We accept those, even when we may not appreciate the quote or link, because there’s no way to say who gets to do what with your content.

Search engines are the prime example here. By scraping the open Web, Google has become one of the world’s most valuable and influential companies. We let Googlebot in because of the implicit agreement that Google will drive traffic to us in return for indexing our content. In fact, Google offers two things in exchange for content sourced from the open Web—traffic to Web publishers and the overall utility of a general-purpose search engine to the world.

But that trade isn’t quite as simple as it seems from the publisher perspective. There are other search engines and many other crawlers. I’m willing to bet that none deliver nearly as much traffic as Google—over 90% of our search engine referrals come from Google, less than 4% from each of DuckDuckGo and Bing, and 1% from Yahoo.

From the user perspective, although we’re still learning what AI chatbots and artbots are good for (see “How to Identify Good Uses for Generative AI Chatbots and Artbots,” 27 May 2024), generative AI opens up entirely new possibilities. Perplexity should be slapped for ignoring robots.txt and hiding its user agent to avoid blocking, but it can be quite helpful in ways that traditional search engines aren’t. It extracts and summarizes key information from a handful of pages that may require non-trivial time to read and parse. The combination of Perplexity and an Apple Intelligence-enhanced Siri makes the concepts in Apple’s 1987 Knowledge Navigator video seem within reach. That’s enticing.

AI crawlers don’t copy the way we think of copying

One of the subtleties of how large language models are built is that they don’t store copied content. An AI crawler has to read the content, which could be construed as copying at some level. However, what it actually does with the content is adjust the weights for each token in the neural network, making certain connections between words slightly more probable and others slightly less probable. Adding more content doesn’t inherently make the model bigger. (Props to Bart Busschots for pointing out this key fact.)

Despite this, it’s possible for a chatbot to regurgitate text from a particular source word for word. The statistical probabilities may work out such that the words in a particular source are more probable than others. It’s not good for a chatbot to do this, but it’s not all that far off from what authors of a lot of derivative content do when summarizing or recasting original articles.

It will be up to the courts to decide if what AI companies are doing counts as copyright infringement. I tend to think that it won’t because copyright protects expressions of ideas, not the ideas themselves. Even if the courts decide that copying is happening, what the AI companies are doing may qualify as fair use if it’s determined to be transformative and not pose a commercial threat to the market for the work.

This may speak to my background as a writer, but my feeling is that artists have a significantly stronger leg to stand on than writers with respect to the market effect. It’s not hard to imagine someone asking an AI artbot to generate an image “in the style of” and being happy enough with the results to avoid hiring the artist. I have a harder time believing that a publisher could do that effectively with text, especially as the length and complexity of the desired output increases.

I like feeling disproportionately represented in LLMs

Ultimately, I’m slightly pleased that generative AI models have trained themselves on so much of my content. That means my authorial and editorial voice is far more heavily represented than that of most other people. It’s an unusual legacy that I never anticipated.