#1440: Music Modernization Act to aid artists, Nisus Writer Pro 3.0 reviewed, TechSoup helps nonprofits get tech discounts

Want to see musicians make a decent living from music streamed via Apple Music or Spotify? See Glenn Fleishman’s coverage of the Music Modernization Act here in the United States, a bipartisan bill that aims to improve the process for everyone involved in music streaming. More interested in serious word processing productivity? Joe Kissell reviews the just-released Nisus Writer Pro 3.0, which is a must for, as he says, anyone who “makes words dance for a living.” Finally, if you’re involved in a nonprofit of any sort, Jeff Porten shows how TechSoup can save your group money on hardware and software. Notable Mac app releases this week include Carbon Copy Cloner 5.1.6, Retrospect 15.6, OmniFocus 3.1.2, Twitterrific 5.3.7, and PopChar X 8.5.

New US Streaming Law Aids Musicians’ Rights and Payments

A gap in US copyright law left some musicians unable to collect royalties during the music-streaming revolution, and others never realized there was money owed to them. The recently enacted Music Modernization Act (MMA) attempts to rationalize a patchwork of common law, state law, and federal law that dates back to the dawn of sound recording in the 1870s.

The MMA combines three different pieces of music-rights legislation and establishes a new way of doing business that is both more fair and more consistent, especially when it comes to Internet radio companies like Pandora and streaming services like Apple Music and Spotify.

Amazingly, the MMA has been received well by every stakeholder, partly due to last-minute changes that tweaked copyright duration. Musicians, independent and major recording labels, digital-music services, and public-domain advocates—even members of Congress who were at various times opposed to some provisions—all have mostly good things to say about the law, even if it’s not precisely what they wanted.

Spotify’s Horacio Gutierrez, the company’s general counsel, said in a statement that the company wants “a million artists” to make a good living creating and performing music. “The Music Modernization Act is a huge step towards making that a reality, modernizing the outdated licensing system to suit the digital world we live in.” (Apple didn’t reply to our request for comment about Apple Music.)

Before the MMA, the music rights held by songwriters and performers were all over the place. For performers, whether they could collect royalties depended on when a song was first recorded (and sometimes, in which state). Producers, mixers, and engineers, often deeply involved in the creative process of making a song or album, received royalties only when it was played or sold in some places.

Streaming services had to apply for rights one song at a time in a cumbersome process that overwhelmed the US Copyright Office, and they could still be hit with lawsuits demanding massive fees if they didn’t find and pay a song’s composer or other rights-holder. Yet many artists remained unpaid, too.

It was a huge mess that cost every party involved time and money, although it particularly shortchanged creators and performers.

Services like Spotify and Apple Music will likely pay more for rights under the new law—both per song and to more artists—which could translate into higher subscription prices. However, those higher costs should be offset by reduced expenses and the elimination of a whole category of potential lawsuits.

Another positive effect? More music could wind up on streaming services, even as artists are paid better for it—or paid at all!

A Patchwork of Laws and Practices

Copyright for visual media like books, film, and television isn’t simple, but at least it’s mostly straightforward. More or less, anything you write, draw, or capture as an image (still or moving) in analog or digital form gets a copyright at the moment of creation. That includes every book, movie, issue of a newspaper, architectural drawing, photograph, and artwork—and musical composition, including variations in arrangements, such as for a quartet, a jazz band, or a full orchestra.

Depending on whether you produce that work for public consumption and whether it’s created directly for a company, copyright lasts from 95 to 120 years from creation, or for 70 years after the last contributor to a work dies.

But sound recordings have always been treated differently. They’re relatively new compared to books and periodicals, with Thomas Edison making the first audio recording in 1877 that could be replayed at will. This led to weird copyright situations, in which the law in the state in which a work was recorded or sold governed ownership. If a state had no specific law, rights were covered by common law—the judicial decisions resulting from criminal or civil cases—which could be all over the place.

Eventually, Congress “federalized” audio copyright, known as the phonogram right, so that all recorded work from 15 February 1972 onward would have a clear set of ownership rights and copyright duration. But Congress also set an absurd expiration. While newly created works had rules similar to those for other kinds of publishing, the copyright on sound recordings made before 15 February 1972 wouldn’t expire until 2067! (Some state laws varied, but for most intents and purposes, that was the date.)

That federalization effort left out more too. It didn’t take into account the potential for new playback technologies that hadn’t yet been imagined. Streaming was particularly problematic because of its particular nature of not transferring music for storage.

One Law to Rule Them All

The MMA solves many of these issues by bringing everything into the same copyright regime. Simultaneously, it establishes a new independent body that will set and collect fees for certain kinds of playback, such as streaming. Here’s a summary of everything that happens.

Copyright Changes

The MMA federalizes all recordings before 15 February 1972. As a result, they’re covered by the same phonogram rights as recordings made on or after that date. As a result, streaming services have to pay performers and other rights holders in those recordings.

A late set of changes to the legislation finally put recordings under a similar set of expiration rules as published works, though it’s complicated. The phonogram rights for all recordings made before 1923 will expire on 1 January 2022. That will open up music locked away in vaults to new listeners and new scholarship.

All work made from 1923 to 1972 gets a term of 95 to 110 years, depending on when it was published. It’s complicated, but recordings from 1923 expire into the public domain on 1 January 2024, followed by annual expirations of subsequent years with a few gaps.

The law also allows non-commercial use of recordings, with a safe harbor for pre-1972 work. If you want to use a song from that era, and you can’t find it in commercial use (actively for sale on a CD or for download, for instance), you can file a notice with the Copyright Office. After 90 days with no response from any rights holder, you can then use the recording with a good assurance that it falls into so-called “fair use.” For some music historians, this will be a boon, even if they can’t sell a product that contains the music.

Clearinghouse for Composition Rights

The MMA creates a new nonprofit organization called the Mechanical Licensing Collective. This group sweeps away the need for every streaming service and digital-music company to track who has a stake in the underlying musical composition of material they deliver. (The “mechanical” right refers to making copies that use a composition. It refers to something like pressing a record—a mechanical process—even though today the process more often involves sending music as bits over the Internet.)

The Mechanical Licensing Collective will be similar to the group that already handles “compulsory licenses,” or the right that allows anyone to perform and release a recording after the first publicly released performance of a song. (This is why “cover” songs abound: the original songwriter has no right to prevent them, and the cost is set at a fixed rate.)

Right now, streaming and download services have to file a notice with the Copyright Office for each song they stream, and the paperwork is unbelievable. The Mechanical Licensing Collective will instead charge a fixed rate for everything and provide a “blanket” license. This change alone will eliminate a vast amount of duplicated and unnecessary effort.

The Mechanical Licensing Collective will also create a publicly searchable database of ownership rights in compositions, something that doesn’t currently exist. It will disburse royalties to those owed them and provide a way for composers and others to stake claims to work for which they aren’t yet listed.

The MMA doesn’t cover rights that have already been sorted out for other aspects of music. These include the fees collected for the sale of audio recordings (whether in analog or digital form), and performance rights in live venues or in movies or on TV. Those rights will still be managed by existing organizations.

Little Things

Producers, sound mixers, and engineers who contributed to a work now get royalties when it’s played on satellite radio or online radio (where a user doesn’t select which songs play), just like they do in other media.

Finally, the Copyright Ruling Board, an obscure group that mostly sets Internet radio royalties, can now consider a song’s popularity in determining how much services should pay to air it.

Pay to Play

In an age in which it seems like the creators of works seldom come out on top, whether it’s due to casual piracy by individuals or collective action by giant corporations, the Music Modernization Act is a surprisingly comprehensive win.

Many musicians will see literally a few dollars more, but some will connect with a revenue stream that could be meaningful. That’s especially true for older artists whose work remains popular and for which they haven’t been compensated at all.

Nisus Writer Pro 3.0 Hits New Levels of Word-Processing Power

Nisus Software has released Nisus Writer Pro 3.0, a major revision to its high-end word processor, after years of development and more than a year of beta testing. The new version has over 300 changes, making it an even more powerful tool than the version it replaces—and yet the company has actually lowered the price from $79 to $65. Upgrades from older editions cost $45, and academic pricing is $55.

This upgrade is a big deal, and I’m incredibly happy about it. If you already use Nisus Writer Pro, you should buy the new version immediately because it will make your work easier and solve problems, saving you time and effort far out of proportion to its cost. And if you’ve been tempted to buy Nisus Writer Pro but weren’t sure that the previous version was quite good enough, you can put those doubts behind you now.

There are those, of course, whose modest word processing needs are adequately met by TextEdit or Google Docs, or to whom it never occurred that Pages or Microsoft Word might have any deficiencies or usability issues. If that describes you, there’s nothing to see here—I’m not going to convince you that you need a better tool. But if you make words dance for a living, you deserve the best word processor you can get, and Nisus Writer Pro is it.

A Quick Retrospective

I reviewed Nisus Writer Pro 2.0 here way back in 2011 (see “Nisus Writer Pro 2.0: The Review,” 8 June 2011). In that article, I recounted some of the history of Nisus Writer and of my own involvement with the app and with Nisus Software, stretching back more than 25 years—including the fact that I wrote a 600-page book, The Nisus Way, about an earlier version of the software in 1995. My impression in 2011 was that version 2.0 was a major leap forward that finally, after many years, made the macOS (then Mac OS X) version of the app a worthy successor to its Classic predecessor, and something I was excited to use every day.

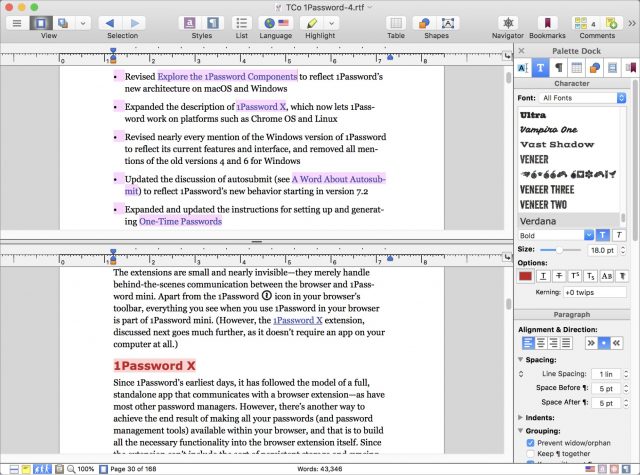

Not long after that, Take Control Books transitioned from Pages to Nisus Writer Pro for all book writing, editing, and production tasks. Because we create long, complex documents with lots of fiddly formatting—and make heavy use of features like change tracking, comments, autonumbering, bookmarks, and dynamic cross-references—the fact that Nisus Writer Pro could finally handle this work at all was noteworthy. But what sold us on switching was that it gave us essential capabilities we couldn’t get in Pages (or in Word, which we’d used previously).

Nisus Writer Pro 2.1 came out in 2015, adding lots of new features and addressing several of the complaints I’d raised in my version 2.0 review. (For example, it added an Edit > Repeat command and made important improvements to the macro language.) It was pretty good, but still lacked a few key capabilities that I longed for, and had some irritating bugs. I kept in touch with Nisus Software, reporting bugs and making sure they were aware of my wish list. Slowly but surely, they’ve addressed the majority of these issues, and many others. I’ve been using beta versions of Nisus Writer Pro 3 since October 2017, and it’s such a remarkable improvement over what was already a solid, reliable tool that I can’t imagine going back.

All the Shiny New Things

The release notes for Nisus Writer Pro 3.0 detail its many new features, enhancements, and bug fixes. But they’re kind of dry and terse, as release notes tend to be, thus underselling the utility of the changes. So I’d like to highlight just a few of the new things I find particularly noteworthy:

- Split View: You can now split a window horizontally or vertically to see more than one part of a document at the same time. (In fact, you can even have multiple splits per window, something I haven’t seen in other word processors.) I said in my 2011 review how much I needed this feature, because I frequently need to compare multiple portions of a manuscript, and it’s beyond tedious to do if you must constantly scroll back and forth. This change alone saves me loads of time and aggravation when writing and editing.

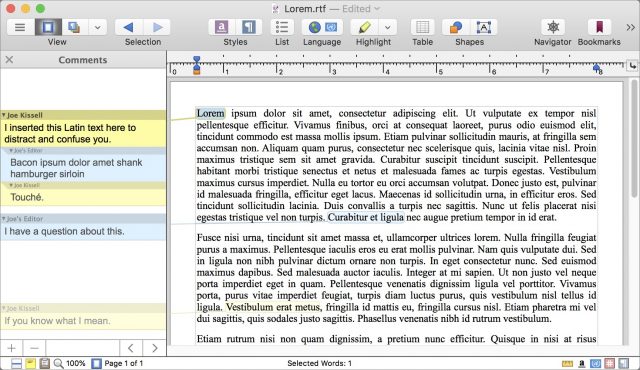

- Better Comments: Nisus Writer Pro now uses a “stacked” and threaded arrangement for comments, similar to what Word does. This makes it much easier for authors and editors to follow a conversation thread than in the previous comment interface.

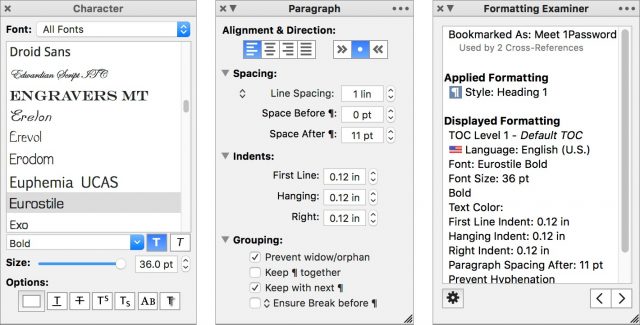

- Interface Improvements: The formatting controls that previously lived in a drawer attached to the side of the window now appear either in a sidebar or as floating palettes that you can position wherever you like. They’re arranged more sensibly, have lots of useful new controls, and are more customizable than before. One particularly nice touch is the new Formatting Examiner palette, which reveals hidden formatting and styles that would otherwise require lots of manual poking around to discover. The toolbar icons are also new and, finally, Retina-friendly. You can now select a line with a single click in the margin much like in Word, although in practice, it usually requires a click and a very slight drag. Oh, and you can now Command-click a plain-text URL to open it in your default browser, just as you can do in BBEdit.

- Cloud Sync for Settings: Nisus Writer Pro can now sync most of its settings (including macros, style library, keyboard shortcuts, and other customizations) across Macs using either iCloud or Dropbox. If you use Nisus Writer Pro on multiple Macs, this saves effort and ensures consistency.

- Find Improvements: The industry’s best find-and-replace capability gets even better, as you can now search all open documents, and find-and-replace results can appear in a separate floating window.

- Synchronized Scrolling: A marvelous feature from the Classic version that has finally reappeared, Synchronized Scrolling lets you lock two windows together, so that as one scrolls, the other scrolls at the same speed. This makes it easy to compare similar documents visually. (You could already use a macro to highlight differences between two documents using change tracking, but that approach, by its very nature, screws up formatting and page breaks.)

- Ensure Break Before ¶: Another feature I requested in my 2011 review, this new paragraph-level style attribute forces a page break before any paragraph bearing that style, which is useful for things like chapter headings. This, again, saves lots of grief and manual effort when producing books.

- New Macro Commands: There are many new or enhanced commands in the macro language, some of which only a macro geek like me would likely appreciate. One of my favorites is a new Image.sourcePixelSize property, which lets me get the dimensions of an image in pixels (rather than bytes or points) programmatically.

- Bug Fixes: Among the long list of fixes were quite a few that plagued Take Control manuscripts. Most crashes and hangs have been eliminated; various weird behaviors with bookmarks, cross-references, and table-of-contents entries are gone; paragraph border, shading, and padding issues have been resolved; macros no longer misbehave if Nisus Writer Pro isn’t in the foreground; automatic hyphenation is less twitchy; and so on. And overall performance has gotten much, much faster.

As I say, this is merely a small sampling—and it includes only things I find relevant in my usage of the product. Hundreds of other improvements will please users of all stripes.

But I Still Have a Wish List

I’m tempted to say I couldn’t be happier with this release, but that would not be entirely true. I could still be just a bit happier.

One feature that I always loved in Word but Nisus Writer Pro still lacks is a way to show multiple pages side-by-side. In Word, I can expand a window to fill up my 27-inch display, click a Multiple Pages button on the View Ribbon, and see as many as eight pages simultaneously at a legible (if barely so) magnification. Although Split View can get me partway there, with a bit of fiddling, it’s not as simple or as elegant as what I can get effortlessly in Word.

Speaking of page views, even with the significant performance enhancements, Nisus Writer Pro spends a lot of time recalculating layouts in longer manuscripts (as evidenced by the frequently appearing “Typesetting Text” dialog), even when I’m doing things that don’t affect the layout at all—and especially often when I’m using Split View. My contact at Nisus Software tells me that this is a consequence of using Apple’s Cocoa text engine (compared to WebKit, which Pages uses, and Word’s custom text engine that apparently relies on Apple’s CoreText framework). Addressing this would require major architectural changes, and realistically, the payoff is unlikely ever to be worth the effort.

Although Nisus Writer Pro can create EPUB ebook files, their formatting is awful—nowhere near sufficient quality that I’d be willing to publish them. Nisus Software tells me they rely on Apple’s framework for exporting documents as EPUB, so they can’t control the details. That’s a pity, and also puzzling since Pages does quite a nice job of creating EPUBs. I can work around this with a complex macro that converts our books to Markdown, and then a local toolchain that converts the Markdown to EPUB, but it’s weird and annoying that I have to jump through all those extra hoops.

I’ve also been wishing for live syntax coloring in Nisus Writer Pro for many years—that’s one of a few reasons I still use BBEdit for editing Markdown, HTML, XML, CSS, PHP, Perl, and other such files.

Finally, a few annoying bugs remain. One of them, which I mentioned back in my review of version 2.0, is that changing the beginning of a bookmarked string of text behaves differently from changing the end, yielding unpredictable (but nearly always wrong) consequences for cross-references to that bookmark elsewhere in your document. Cross-references also break if I select an entire image caption and type over it, whereas they’re fine if I change everything except the first character. In addition, I’ve seen a behavior many times in which I delete a chunk of text that includes some type of heading, and then undo that deletion to find that the heading’s style has changed, and can’t be restored with any number of undos. (Frustratingly, for as many times as I’ve encountered this, I’ve never been able to reproduce it twice in a row on the same document, which makes it a tough bug to track down.)

Parting Details

Nisus Writer Pro 3.0 is available either directly from Nisus Software or from the Mac App Store, and it’s a 334 MB download. Also available is Nisus Writer Express, a version of the app with a much smaller feature set (and a lower price to match: $20). The current version of Nisus Writer Express, 3.5.10, is still based on the old Nisus Writer code base, so it does not share the interface improvements or new features of Nisus Writer Pro 3.0.

Finally, for those who will inevitably ask: sorry, but the likelihood that I’ll ever write a new book about Nisus Writer is close to zero. The Take Control Customer Survey we conducted a few months ago asked about interest in a book on Nisus Writer Pro, and it didn’t even make the top ten third-party apps. That, combined with a variety of other data points, tells me that my efforts would be better directed elsewhere, but if public interest in Nisus Writer Pro skyrockets thanks to version 3 (which of course it should!), perhaps I’ll revisit that decision.

TechSoup: Get Deep Discounts on Technology for Your Nonprofit

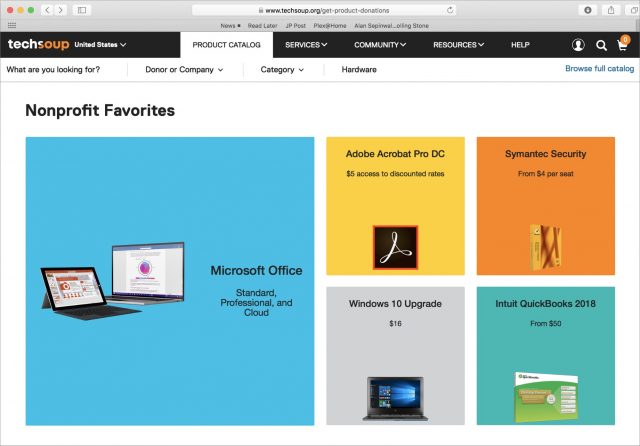

I recently took the helm of an educational science nonprofit. Like any good technocrat, my first instinct was to find tools to automate and streamline our management and communications infrastructure. Just about every major tech company advertises—sometimes loudly, sometimes selectively—that they provide free or discounted services to people doing good work, but finding and accessing those resources can be tricky. But it’s worth it if, for instance, you want to get Microsoft Office for your nonprofit at a 95% discount.

Thankfully, there’s an organization that acts as a clearinghouse for such things: TechSoup. Although TechSoup is a great deal and provides an extensive catalog of resources, it can be difficult to make good use of it. Here’s how TechSoup works.

TechSoup for the Soul (and Groups That Aren’t Churches, Too)

TechSoup exists because the problem of matching resources to organizations happens in both directions. Say you’re Adobe and you want to donate your software to folks doing good things. You can’t just open the floodgates to everyone. If you offer Creative Cloud at a discount to everyone who volunteers for a Parent-Teacher Association, pretty soon all your customers will bake cookies once a year to save $400.

Instead, companies like Adobe—over 80 of them right now—outsource the selection process to TechSoup, which in turn passes it along to the Internal Revenue Service. If your organization has a 501(c)(3) designation from the IRS, you’re “probably” eligible (to quote the TechSoup sign-up page), and there’s a form where you can check if you are. Religious organizations are likely also categorized as 501(c)(3). Also included are any libraries registered in the Institute of Museum and Library Services database, regardless of their 501(c)(3) designation. Excluded are nonprofits organized under different tax subchapters, such as the 501(c)(4) designation for nonprofits engaged in political activity. If you’re international, you’re also in luck, as TechSoup operates globally.

Somewhat oddly, schools that don’t have 501(c)(3) status can’t use TechSoup. Public schools are governmental entities and can’t get such status. For private schools, it comes down to the business structure of the school and perhaps the mood of the tax examiner. In any case, unless you’re running the school and can control what tax designation it uses, there’s nothing you can do to gain status. You might be able to form a separate 501(c)(3) to run educational programs the school cannot, or you might do so under the umbrella of a nearby community organization with 501(c)(3) status. However, all such nonprofits would still need to apply and qualify for TechSoup, as membership is never automatic.

Forming a nonprofit is not insanely difficult, but not for everyone. I’ve been involved in several “nonprofit-ish” organizations that decided to remain unincorporated. It’s not just the application process that can be complicated; it’s also dealing with the ongoing compliance procedures to make sure your status isn’t later revoked. And having your status revoked can come with legal and tax penalties if you operated in for-profit ways while you had a nonprofit exemption. Operating as a nonprofit becomes much easier if two of your volunteers are a lawyer and an accountant.

Historically, the main reason you would do this is so your members could deduct their donations to you from their income taxes, but 2018 revisions to the tax code changed it so they have to donate more money (to all nonprofits collectively) before they get any personal benefit from doing so.

All that said, if I were running an unincorporated nonprofit, TechSoup would be a significant reason to incorporate as a 501(c)(3); the benefits it provides are pretty good if they match what you need.

Getting Into the Soup

Applying to TechSoup is free, and it’s free to be a member; you don’t incur any costs until you ask for stuff. TechSoup terms this, somewhat oddly (and perhaps misleadingly) as a “fee” for a “donation.” Do you want a free copy of Microsoft Office for Mac? That’ll be a $29 fee, please.

But that’s a nice 95% discount off the $588 market value reported in the resulting email; this isn’t the Home and Student edition anyone can get for cheap. Since the size of the fees roughly correlates to the value of what you’re asking for, it’s the equivalent of paying a fraction of the retail cost to TechSoup for what you get. That fraction varies by product; software and services get nice discounts, but hardware less so.

Setup requires a three-step process:

- Sign up for your personal account as a member of TechSoup.

- Register your organization with TechSoup and request to be validated. (If you’re not a 501(c)(3) or a library, you won’t get past this step.)

- Set up your personal account as an authorized agent for that organization. A member can act as the agent for multiple organizations, and an organization can have multiple agents.

If you’re a volunteer setting up an existing nonprofit, you’ll need someone in the organization to provide you with documentation proving your status. Among other documents, I had to send in the determination letter from the IRS proving our status, even though such proof is readily available online since the tax filings of all 501(c)(3)s are public. TechSoup uses these documents to both qualify the organization and as implicit proof that you’re approved to act as their agent, because you’d need internal support to have copies.

The process took about a week, but my organization was already signed up—I didn’t have to qualify it, only myself. TechSoup says the organizational step takes up to seven business days, which is in addition to whatever time is necessary to make you an authorized agent.

However, even once your organization is validated and you’re the agent, you don’t necessarily qualify for everything TechSoup has in its product catalog. That’s because every donor can set additional rules per product, and a human reviews every request. Organizations with larger budgets may be turned down for some donations, and there may be limits on how many licenses, seats, or hardware units you can request.

There are also terms and conditions for what you can do with donations once you receive them. You’re not allowed to transfer ownership outside the organization, so you can’t buy 100 copies of Office and give them away to your biggest donors. However, this leaves a gray area because many volunteers legitimately qualify as part of their work. How each nonprofit determines a “qualified volunteer” is a loophole large enough to march a Salvation Army battalion through. TechSoup monitors donation requests and may take action if it spots a violation, which could range from a pleasant communication clarifying the relevant policies to termination of your membership.

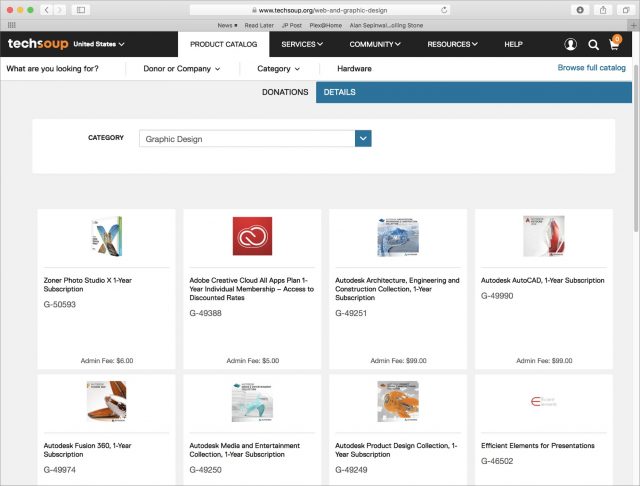

What’s on Offer

The slam-dunk reason to sign up for TechSoup is free access to Google’s G Suite and Microsoft Office 365 (the version that doesn’t include the downloadable apps). Either of these would cost thousands of dollars annually for an organization the size of mine. My interest in G Suite is what led me to TechSoup in the first place, since it’s the only way to get Google’s nonprofit offerings. In both these cases, after TechSoup approves the donation, there’s an additional process with each company, and it’s convoluted enough that I’ve purchased but haven’t yet activated either my Office for Mac apps or Office 365. (Which is to say, I needed G Suite so I stuck with it; I don’t have a pressing need for Microsoft’s apps, so I haven’t yet made the time.)

Other software and services get good discounts, but not as high as the 95% off I got for Office for Mac or the 100% off for G Suite. Adobe Creative Cloud will run you $19.99 per month versus the $52.99 per month retail price (for the first year; it may be higher after that but still “at least” 40% off). FileMaker is here in a five-user server package for $540 per year; that’s roughly 80% off the retail price, but you can’t buy a single copy.

The only slam-dunk hardware I’ve found so far is the Mobile Beacon device and unlimited data plan, which is designed to provide mobile Internet access for nonprofits. It’s a small device about the size of a 1990s-era pager that gives you a mobile Wi-Fi hotspot. For $120 total, it provides a year of unlimited data on the Sprint network. Its definition of “unlimited” is more generous than the usual: after 23 GB per month, your connection will be throttled, but only in the case of network congestion. I haven’t yet hit that cap to test it. What I can say is that comparing the speed to what I can get on my Project Fi phone when it’s using Sprint, Mobile Beacon is slower but not egregiously so. I’m paying roughly $10 per month to cut $40–$60 off my phone bill so I’m happy with a little slower. You can also order directly through Mobile Beacon, which still requires nonprofit status but not necessarily 501(c)(3); notably, schools can use Mobile Beacon to provide disadvantaged students with Internet access at home.

The rest of TechSoup’s hardware is less exciting. There’s a refurbished section that’s mostly Windows hardware. I’ve seen a mid-2011 iMac and an early-2015 MacBook Air there, both for higher fees than you can find elsewhere. I can’t tell if the Windows hardware is a bargain—some laptops I spot-checked were more expensive than Amazon pricing, but one or two had a deep enough discount that I wasn’t sure if I was comparing apricots to oranges. Some companies—not including Apple—offer programs along the lines of “pay a $10 fee for a 30% discount on new products on our Web site.” If you need to furnish an office or buy mid-range professional hardware like a Cisco switch, this could save a bundle.

There may be other software packages just as enticing to your organization as G Suite was to me. For example, we’re evaluating a product available through TechSoup for where our accounting infrastructure will live.

TechSoup also offers a range of services over and above its catalog. You can sign up for the Boost program for $79 a year, which lowers the fees on some items. TechSoup even has an IT consulting and help desk infrastructure that you can sign up for as needed or with annual subscriptions. It might not replace the need for an IT department, but if your nonprofit doesn’t have the expertise to know what questions to ask, these services will get you started.

Finally—not every company is here. My organization also receives free services from Salesforce, and what we get there would cost over five figures if we were for-profit. But even as someone who’s worked with similar software for 20 years, I found Salesforce’s services to be completely incomprehensible. As my account representative confirmed, one reason Salesforce offers them for free is that the company expects some percentage of nonprofit subscribers to pay for training and consulting services. In other words, if there’s something you want, it can never hurt to ask if a company has a nonprofit program of their own—at which point, look for the hidden gotchas before committing.

I recommend TechSoup for G Suite, Office 365, and Mobile Beacon alone, but the top reason for my recommendation is that, as a one-stop shop for technology needs in my volunteer work, TechSoup focuses my planning and cuts down on the time I have to spend searching. And that’s the real limiting factor for this kind of thing. If you’re involved in a nonprofit that could use more technology infrastructure than you can afford, give TechSoup a try.

Josh Centers

1

comment

Josh Centers

1

comment

Josh Centers

5

comments

Josh Centers

5

comments