#1574: FAQ about Apple’s “Expanded Protections for Children,” control third-party displays with Lunar, signing group cards during a pandemic

Apple ignited a firestorm of controversy last week when it announced new features designed to protect children by scanning iCloud Photos uploads for known child sexual abuse material and identifying images of a sensitive nature in Messages. Glenn Fleishman and Rich Mogull have compiled an extensive FAQ on how the technology works and how Apple is responding to privacy concerns. If you’ve had trouble controlling brightness on a third-party display from an M1-based Mac, we can explain why. New contributor TJ Luoma reviews Lunar, a utility that implements a technology missing in M1-based Macs to control third-party displays. Finally, Adam Engst wanted his running group to sign a card for a departing friend but struggled to figure out how to pull it off during the pandemic. He shares his solution so others can learn from his research. Notable Mac app releases this week include Quicken 6.3, Alfred 4.5, Ulysses 23.1, and Art Text 4.1. ![]()

A Solution for Group “Best Wishes” Certificates During the Pandemic

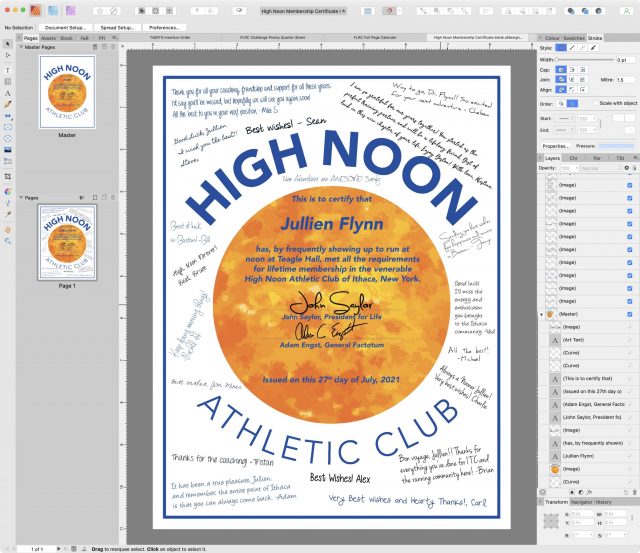

The High Noon Athletic Club that I run with has a tradition, or at least it did before the pandemic. To commemorate when one of our regulars moves away, we mark the event with a “last run,” complete with libations at a nearby creek and a membership certificate that was secretly passed around in the locker room for the rest of the group to affix their best wishes. One of our members recently completed her PhD and was headed off for a postdoc at MIT, but since noontime runs aren’t yet happening regularly, there was no way to collect signatures.

Rather than let another tradition fall prey to the pandemic, I came up with a solution that I’d like to share in case anyone else finds themselves in a similar situation. My approach had to meet a few requirements:

- People had to be able to write whatever message they wanted.

- The messages on the membership certificate had to look handwritten, but not as though they were all written by the same person with the same pen.

- It couldn’t require any time-consuming graphics work in cleaning up scanned or photographed messages.

To collect the messages, I set up a Google Form with a single short answer question and sent the link to the club mailing list. I encouraged people to keep their messages brief, though I wasn’t surprised when a few got wordy.

Many people don’t realize that Google Forms can save responses to a Google Sheet, making it easy to work with the data after the fact. That got me the data I needed, in a form that made it easy to copy and paste.

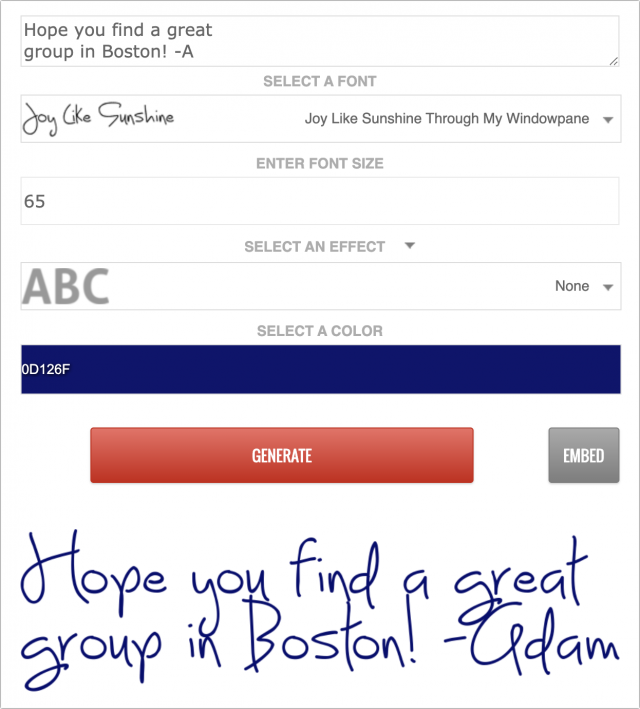

The linchpin for the project was Font Meme’s Text Graphic Generator for Handwriting Fonts. It let me enter some text, choose from a wide variety of handwriting fonts, and pick a color, after which it turned my text into a PNG graphic. Once I was satisfied, it was easy to Control-click the graphic and choose Copy Image.

Next, I opened our membership certificate in Affinity Publisher. (I’m converting all my projects from Adobe InDesign and Adobe Illustrator to Affinity Publisher and Affinity Designer because they each cost about the same as a single month of Adobe’s Creative Cloud). I pasted the message in, resized it to fit in an empty area, and angled it so it looked more like someone was trying to fit it into a particular spot. Then I repeated the process with all the other messages, choosing a different font for each. I had to insert returns into a few of them to make them more vertical than horizontal, and for some, I changed the color from black to blue to simulate people writing with different pens. It took a little work to resize and arrange them all in a realistic fashion, but the end result came out great and was significantly cleaner (and less sweat-stained) than our usual efforts.

This little project is far from being a cure for cancer, but it was a good feeling to be able to leverage various tools to do something nice for a departing friend. I hope others find it helpful as well.

Total Eclipse of the Mac: Lunar Controls Third-Party Displays

Not long after I received my M1-based Mac mini, I was working late in the night and decided to decrease the brightness of my Dell monitor. I reached up and pressed the F1 key on my Magic Keyboard as I had done for as long as I could remember. Nothing happened. I tried again but to no avail.

For the past several years, I’ve used a series of MacBooks—a 12-inch MacBook, a MacBook Air, and a 16-inch MacBook Pro. This was my first time using a Mac mini with an external monitor as my primary computer. I assumed I’d be able to control the brightness on my monitor using the standard keys on a Mac keyboard or the brightness slider in System Preferences > Displays.

I was wrong. It turns out that Macs can’t necessarily control the brightness on external displays with built-in options. Of course, that’s not a problem with Apple monitors like the older Thunderbolt Display, today’s insanely expensive Pro Display XDR, or the Apple-approved LG UltraFine monitors.

For reasons I don’t understand, macOS lacks built-in support for these settings when using a third-party display apart from the few models mentioned above. However, owners of Intel-based Macs can use various command-line and graphical tools for this purpose, but none seemed to work on my M1-based Mac mini. I started digging deeper and realized I wasn’t alone: each of these tools had someone commenting that it did not work with M1-based Macs and it was not a problem that Rosetta could solve.

The reason seems to be that M1-based Macs lack support for DDC or Display Data Channel, a standard set of control protocols that monitors have used for many years. Every tool that I could find needed DDC support, which is why none worked on M1-based Macs.

Obviously, I could use my Dell monitor’s buttons, like some kind of animal, but as everyone knows: they’re terrible. My monitor has four buttons along the bottom, but they don’t adjust the brightness or contrast. That would be too easy. To control those settings, I have to navigate the monitor’s onscreen menu hierarchy, which requires pressing one of the buttons, using another button to go up or down to the right sub-menu, pushing a third button to select brightness, and going back to a previous button to adjust the brightness up or down. It’s slow, it’s clunky, and I always press the wrong buttons and end up feeling like an idiot. Eventually, I found an app that could control brightness and contrast directly from my M1-based Mac mini.

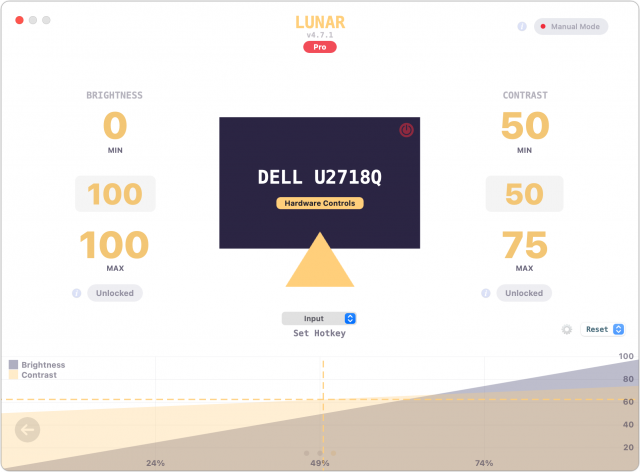

Developed by Alin Panaitiu, Lunar had a steady stream of development, culminating in its official release at the end of May 2021. Its website showed a bevy of options, including a wide range of customizable keyboard shortcuts. Even cooler, it could control the brightness automatically based on your location and sync the brightness of an external monitor with a MacBook’s built-in monitor. Most importantly, it just worked, and it worked reliably.

Back then, Lunar made use of an impressive hack for those of us who wanted to use an M1-based Mac. For such Macs, Lunar’s best hardware-based solution relied on a Raspberry Pi to relay commands from a Mac to the external HDMI monitor. Since the Raspberry Pi supported DDC, this was almost as good as a native solution… if you had a Raspberry Pi. I did, and I set up this “network control” approach, which was as simple as entering my Raspberry Pi username and password, and then selecting a menu option from Lunar. (Lunar also has a software-only solution that relied on adjusting gamma values, but that conflicted with utilities like f.lux that also use gamma, could only lower—not increase—the brightness, and lacked other monitor controls for volume and input.)

But Panaitiu didn’t stop there. With some help from other developers who contributed to the project, he recently added native DDC support for M1-based Macs to Lunar 4.5.1, so there’s no need for a Raspberry Pi or a software-only solution. You may still run into issues due to bugs in monitor firmware, but Lunar’s FAQ explains many of those issues. (And if you’re really interested in the backstory and technical details, see Panaitiu’s blog post about how getting an M1-based Mac caused him to quit his job and focus on Lunar.)

Now I can control my Dell monitor directly via my M1-based Mac mini, complete with the onscreen display when settings change. It does require that I use one of the Thunderbolt ports rather than the Mac mini’s HDMI port (the combination of that port and the Mac mini’s video driver just won’t send DDC messages, for some reason), but I can use the standard macOS keys for native brightness and contrast changes, or use Lunar’s preferences to set my own shortcuts.

And you can too, as long as you’re running macOS 10.15 Catalina or later. Lunar is free, but some of its fancier features require a $23 Pro license. I was only too happy to support the project. Sure, in a perfect world, we’d never need third-party software to add support for protocols Apple should build in, but in the here and now, $23 seemed like a small price to pay to support an active and creative developer. Plus, TidBITS members can save 30%, dropping the price to $16.10 and making it an even easier decision.

TJ Luoma is a Presbyterian pastor and computer nerd in Plattsburgh, New York. His first Mac was a NeXTStation he used in college in the early ‘90s, and he helped run the PEAK FTP site for NeXTStep/OpenStep software back in the mid-late ‘90s. More recently, he has written for TUAW and MacStories, and been a guest on the Mac Power Users and Automators podcasts. You can find him on Twitter as @tjluoma or at his website RhymesWithDiploma.com.

FAQ about Apple’s Expanded Protections for Children

Two privacy changes that Apple intends to reduce harm to children will roll out to iCloud Photos and Messages in the iOS 15, iPadOS 15, and macOS 12 Monterey releases in the United States.

The first relates to preventing the transmission and possession of photos depicting the sexual abuse of minor children, formally known by the term Child Sexual Abuse Material (CSAM) and more commonly called “child pornography.” (Since children cannot consent, pornography is an inappropriate term to apply, except in certain legal contexts.) Before photos are synced to iCloud Photos from an iPhone or iPad, Apple will compare them against a local cryptographically obscured database of known CSAM.

The second gives parents the option to enable on-device machine-learning-based analysis of all incoming and outgoing images in Messages to identify those that appear sexual in nature. It requires Family Sharing and applies to children under 18. If enabled, kids receive a notification warning of the nature of the image, and they have to tap or click to see or send the image. Parents of children under 13 can additionally choose to get an alert if their child proceeds to send or receive “sensitive” images.

Apple will also update Siri and Search to recognize unsafe situations, provide contextual information, and intervene if users search for CSAM-related topics.

As is always the case with privacy and Apple, these changes are complicated and nuanced. Over the past few years, Apple has emphasized that our private information should remain securely under our control, whether that means messages, photos, or other data. Strong on-device encryption and strong end-to-end encryption for sending and receiving data have prevented both large-scale privacy breaches and the more casual intrusions into what we do, say, and see for advertising purposes.

Apple’s announcement headlined these changes as “Expanded Protections for Children.” That may be true, but it could easily be argued that Apple’s move jeopardizes its overall privacy position, despite the company’s past efforts to build in safeguards, provide age-appropriate insight for parents about younger children, and rebuff governments that have wanted Apple to break its end-to-end encryption and make iCloud less private to track down criminals (see “FBI Cracks Pensacola Shooter’s iPhone, Still Mad at Apple,” 19 May 2020).

You may have a lot of questions. We know we did. Based on our experience and the information Apple has made public, here are answers to some of what we think will be the most common ones. After a firestorm of confusion and complaints, Apple also released its own Expanded Protections for Children FAQ, which largely confirms our analysis and speculation.

Question: Why is Apple announcing these technologies now?

Answer: That’s the big question. Even though this deployment is only in the United States, our best guess is that the company has been under pressure from governments and law enforcement worldwide to participate more in government-led efforts to protect children.

Word has it that Apple, far from being the first company to implement such measures, is one of the last of the big tech firms to do so. Other large companies keep more data in the cloud, where it’s protected only by the company’s encryption keys, making it more readily accessible to analysis and warrants. Also, the engineering effort behind these technologies undoubtedly took years and cost many millions of dollars, so Apple’s motivation must have been significant.

The problem is that exploitation of children is a highly asymmetric problem in two different ways. First, a relatively small number of people engage in a fairly massive amount of CSAM trading and direct online predation. The FBI notes in a summary of CSAM abuses that several hundred thousand participants were identified across the best known peer-to-peer trading networks. That’s just part of the total, but a significant number of them. The University of New Hampshire’s Crimes Against Children Research Center found in its research that “1 in 25 youth in one year received an online sexual solicitation where the solicitor tried to make offline contact.” The Internet has been a boon for predators.

The other form of asymmetry is adult recognition of the problem. Most adults are aware that exploitation happens—both through distribution of images and direct contact—but few have personal experience or exposure themselves or through their children or family. That leads some to view the situation somewhat abstractly and academically. Those who are closer to the problem—personally or professionally—may see it as a horror that must be stamped out, no matter the means. Where any person comes down on how far tech companies can and should go to prevent exploitation of children likely depends on where they are on that spectrum of experience.

CSAM Detection

Q: How will Apple recognize CSAM in iCloud Photos?

A: Obviously, you can’t build a database of CSAM and distribute it to check against because that database would leak and re-victimize the children in it. Instead, CSAM-checking systems rely on abstracted fingerprints of images that have been vetted and assembled by the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (NCMEC). The NCMEC is a non-profit organization with a quasi-governmental role that allows the group to work with material that is otherwise illegal to possess. It’s involved in tracking and identifying newly created CSAM, finding victims depicted in it, and eliminating the trading of existing images. (The technology applies only to images, not videos.)

Apple describes the CSAM recognition process in a white paper. Its method allows the company to take the NCMEC database of cryptographically generated fingerprints—called hashes—and store that on every iPhone and iPad. (Apple hasn’t said how large the database is; we hope it doesn’t take up a significant percentage of a device’s storage.) Apple generates hashes for images a user’s device wants to sync to iCloud Photos via a machine-learning algorithm called NeuralHash that extracts a complicated set of features from an image. This approach allows a fuzzy match against the NCMEC fingerprints instead of an exact pixel-by-pixel match—an exact match could be fooled by changes to an image’s format, size, or color. Howard Oakley has a more technical explanation of how this works.

Apple passes the hashes through yet another series of cryptographic transformations that finish with a blinding secret that stays stored on Apple’s servers. This makes it effectively impossible to learn anything about the hashes of images in the database that will be stored on our devices.

Q: How is CSAM Detection related to iCloud Photos?

A: You would be forgiven if you wondered how this system is actually related to iCloud Photos. It isn’t—not exactly. Apple says it will only scan and check for CSAM matches on your iPhone and iPad for images that are queued for iCloud Photos syncing. A second part of the operation happens in the cloud based on what’s uploaded, as described next.

Images already stored in your iCloud accounts that were previously synced to iCloud Photos won’t be scanned. However, nothing in the system design would prevent all images on a device from being scanned. Nor is Apple somehow prohibited from later building a cloud-scanning image checker. As Ben Thompson of Stratechery pointed out, this is the difference between capability (Apple can’t scan) and policy (Apple won’t scan).

Apple may already be scanning photos in the cloud. Inc. magazine tech columnist Jason Aten pointed out that Apple’s global privacy director Jane Horvath said in a 2020 CES panel that Apple “was working on the ability.” MacRumors also reported her comments from the same panel: “Horvath also confirmed that Apple scans for child sexual abuse content uploaded to iCloud. ‘We are utilizing some technologies to help screen for child sexual abuse material,’ she said.” These efforts aren’t disclosed on Apple’s site, weren’t discussed this week, and haven’t been called out by electronic privacy advocates.

However, in its 2020 list of reports submitted by electronic service providers, NCMEC says that Apple submitted only 265 reports to its CyberTipline system (up from 205 in 2019), compared with 20,307,216 for Facebook, 546,704 for Google, and 96,776 for Microsoft. Apple is legally required to submit reports, so if it were scanning iCloud Photos, the number of its reports would certainly be much higher.

Q. How does Apple match images while ostensibly preserving privacy?

A: All images slated for upload to iCloud Photos are scanned, but matching occurs in a one-way process called private set intersection. As a result, the owner of a device never knows that a match occurred against a given image, and Apple can’t determine until a later stage if an image matched—and then only if there were multiple matches. This method also prevents someone from using an iPhone or iPad to test whether or not an image matches the database.

After scanning, the system generates a safety voucher that contains the hash produced for an image, along with a low-resolution version of the image. A voucher is uploaded for every image, preventing any party (the user, Apple, a government agency, a hacker, etc.) from using the presence or absence of a voucher as an indication of matches. Apple further seeds these uploads with a number of generated false positive matches to ensure that even it can’t create an accurate running tally of matches.

Apple says it can’t decrypt these safety vouchers unless the iCloud Photos account crosses a certain threshold for the quantity of CSAM items. This threshold secret sharing technology is supposed to reassure users that their images remain private unless they are actually actively trafficking in CSAM.

Apple encodes two layers of encryption into safety vouchers. The outer layer derives cryptographic information from the NeuralHash of the image generated on a user’s device. For the inner layer, Apple effectively breaks an on-device encryption key into a number of pieces. Each voucher contains a fragment. For Apple to decode safety vouchers, an undisclosed number of images must match CSAM fingerprints. For example, you might need 10 out of 1000 pieces of the key to decrypt the vouchers. (Technically, we should use the term secret instead of key, but it’s a bit easier to think of it as a key.)

This two-layer approach lets Apple check only vouchers that have matches without being able to examine the images within the vouchers. Only once Apple’s servers determine a threshold of vouchers with matching images has been crossed can the secret be reassembled and the matching low-resolution previews extracted. (The threshold is set in the system’s design. While Apple could change it later, that would require recomputing all images according to the new threshold.)

Using a threshold of a certain number of images reduces the chance of a single false positive match resulting in serious consequences. Even if the false positive rate were, say, as high as 0.01%, requiring a match of 10 images would nearly eliminate the chance of an overall false positive result. Apple writes in its white paper, “The threshold is selected to provide an extremely low (1 in 1 trillion) probability of incorrectly flagging a given account.” There are additional human-based checks after an account is flagged, too.

Our devices also send device-generated false matches. Since those false matches use a fake key, Apple can decrypt the outer envelope but not the inner one. This approach means Apple never has an accurate count of matches until the keys all line up and it can decrypt the inner envelopes.

Q: Will Apple allow outside testing that its system does what it says?

A: Apple controls this system entirely and appears unlikely to provide an outside audit or more transparency about how it works. This stance would be in line with not allowing ne’er-do-wells more insight into how to beat the system, but also means that only Apple can provide assurances.

In its Web page covering the child-protection initiatives, Apple linked to white papers by three researchers it briefed in advance (see “More Information” at the bottom of the page). Notably, two of the researchers don’t mention if they had any access to source code or more than a description of the system as provided in Apple’s white paper.

A third, David Forsyth, wrote in his white paper, “Apple has shown me a body of experimental and conceptual material relating to the practical performance of this system and has described the system to me in detail.” That’s not the kind of outside rigor that such a cryptographic and privacy system deserves.

In the end, as much as we’d like to see otherwise, Apple has rarely, if ever, offered even the most private looks at any of its systems to outside auditors or experts. We shouldn’t expect anything different here.

Q: How will CSAM scanning of iCloud Photos affect my privacy?

A: Again, Apple says it won’t scan images that are already stored in iCloud Photos using this technology, and it appears that the company hasn’t already been scanning those. Rather, this announcement says the company will perform on-device image checking against photos that will be synced to iCloud Photos. Apple says that it will not be informed of specific matches until a certain number of matches occurs across all uploaded images by the account. Only when that threshold is crossed can Apple gain access to the matched images and review them. If the images are indeed identical to matched CSAM, Apple will suspend the user’s account and report them to NCMEC, which coordinates with law enforcement for the next steps.

It’s worth noting that iCloud Photos online storage operates at a lower level of security than Messages. Where Messages employs end-to-end encryption and the necessary encryption keys are available only to your devices and withheld from Apple, iCloud Photos are synced over secure connections but are stored in such a way that Apple can view and analyze them. This design means that law enforcement could legally compel Apple to share images, which has happened in the past. Apple pledges to keep iCloud data, including photos and videos, private but can’t technically prevent access as it can with Messages.

Q: When will Apple report users to the NCMEC?

A: Apple says its matching process requires multiple images to match before the cryptographic threshold is crossed that allows it to reconstruct matches and images and produce an internal alert. Human beings then review matches—Apple describes this as “manually”—before reporting them to the NCMEC.

There’s also a process for an appeal, though Apple says only, “If a user feels their account has been mistakenly flagged they can file an appeal to have their account reinstated.” Losing access to iCloud is the least of the worries of someone who has been reported to NCMEC and thus law enforcement.

(Spare some sympathy for the poor sods who perform the “manual” job of looking over potential CSAM. It’s horrible work, and many companies outsource the work to contractors, who have few protections and may develop PTSD, among other problems. We hope Apple will do better. Setting a high threshold, as Apple says it’s doing, should dramatically reduce the need for human review of false positives.)

Q. Couldn’t Apple change criteria and scan a lot more than CSAM?

A: Absolutely. Whether the company would is a different question. The Electronic Frontier Foundation states the problem bluntly:

…it’s impossible to build a client-side scanning system that can only be used for sexually explicit images sent or received by children. As a consequence, even a well-intentioned effort to build such a system will break key promises of the messenger’s encryption itself and open the door to broader abuses.

There’s no transparency anywhere in this entire system. That’s by design, in order to protect already-exploited children from being further victimized. Politicians and children’s advocates tend to brush off any concerns about how efforts to detect CSAM and identify those receiving or distributing it may have large-scale privacy implications.

Apple’s head of privacy, Erik Neuenschwander, told the New York Times, “If you’re storing a collection of C.S.A.M. material, yes, this is bad for you. But for the rest of you, this is no different.”

Given that only a very small number of people engage in downloading or sending CSAM (and only the really stupid ones would use a cloud-based service; most use peer-to-peer networks or the so-called “dark web”), this is a specious remark, akin to saying, “If you’re not guilty of possessing stolen goods, you should welcome an Apple camera in your home that lets us prove you own everything.” Weighing privacy and civil rights against protecting children from further exploitation is a balancing act. All-or-nothing statements like Neuenschwander’s are designed to overcome objections instead of acknowledging their legitimacy.

In its FAQ, Apple says that it will refuse any demands to add non-CSAM images to the database and that its system is designed to prevent non-CSAM images from being injected into the system.

Q: Why does this system concern civil rights and privacy advocates?

A: Apple created this system of scanning user’s photos on their devices using advanced technologies to protect the privacy of the innocent—but Apple is still scanning users’ photos on their devices without consent (and the act of installing iOS 15 doesn’t count as true consent).

It’s laudable to find and prosecute those who possess and distribute known CSAM. But Apple will, without question, experience tremendous pressure from governments to expand the scope of on-device scanning. This is a genuine concern since Apple has already been forced to compromise its privacy stance by oppressive regimes, and even US law enforcement continues to press for backdoor access to iPhones. Apple’s FAQ addresses this question directly, saying:

We have faced demands to build and deploy government-mandated changes that degrade the privacy of users before, and have steadfastly refused those demands. We will continue to refuse them in the future. Let us be clear, this technology is limited to detecting CSAM stored in iCloud and we will not accede to any government’s request to expand it.

On the other hand, this targeted scanning could reduce law-enforcement and regulatory pressure for full-encryption backdoors. We don’t know how much negotiation behind the scenes with US authorities took place for Apple to develop this solution, and no current government officials are quoted in any of Apple’s materials—only previous ones, like former U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder. Apple has opened a door of possibility, and no one can know for sure how it will play out over time.

Security researcher Matthew Green, a frequent critic of Apple’s lack of transparency and outside auditing of its encryption technology, told the New York Times:

They’ve been selling privacy to the world and making people trust their devices. But now they’re basically capitulating to the worst possible demands of every government. I don’t see how they’re going to say no from here on out.

Image Scanning in Messages

Q: How will Apple enable parental oversight of children sending and receiving images of a sexual nature?

A: Apple says it will build a “communication safety” option into Messages across all its platforms. It will be available only for children under 18 who are part of a Family Sharing group. (We wonder if Apple may be changing the name of Family Sharing because its announcement calls it “accounts set up as families in iCloud.”) When this feature is enabled, device-based scanning of all incoming and outgoing images will take place on all devices logged into a kid’s account in Family Sharing.

Apple says it won’t have access to images, and machine-learning systems will identify the potentially sexually explicit images. Note that this is an entirely separate system from the CSAM detection. It’s designed to identify arbitrary images, not match against a known database of CSAM.

Q: What happens when a “sensitive image” is received?

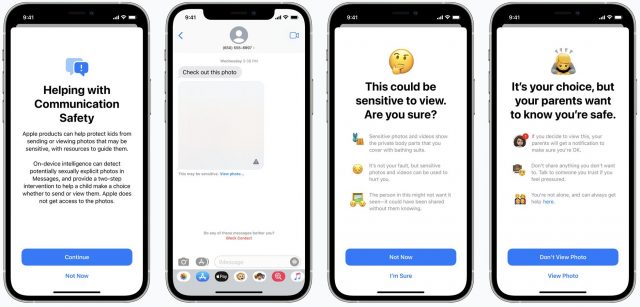

A: Messages blurs the incoming image. The child sees an overlaid warning sign and a warning below the image that notes, “This may be sensitive. View photo…” Following that link displays a full-screen explanation headed, “This could be sensitive to view. Are you sure?” The child has to tap “I’m Sure” to proceed.

For children under 13, parents can additionally require that their kids’ devices notify them if they follow that link. In that case, the child is alerted that their parents will be told. They must then tap “View Photo” to proceed. If they tap “Don’t View Photo,” parents aren’t notified, no matter the setting.

Q: What happens when children try to send “sensitive images”?

A: Similarly, Messages warns them about sending such images and, if they are under 13 and the option is enabled, alerts them that their parents will be notified. If they don’t send the images, parents are not notified.

Siri and Search

Q: How is Apple expanding child protection in Siri and Search?

A: Just as information about resources for those experiencing suicidal ideation or knowing people in that state now appears in relevant news articles and is offered by home voice assistants, Apple is expanding Siri and Search to acknowledge CSAM. The company says it will provide two kinds of interventions:

- If someone asks about CSAM or reporting child exploitation, they will receive information about “where and how to file a report.”

- If someone asks or searches for exploitative material related to children, Apple says, “These interventions will explain to users that interest in this topic is harmful and problematic, and provide resources from partners to get help with this issue.”

Has Apple Opened Pandora’s Box?

Apple will be incredibly challenged to keep this on-device access limited to a single use case. Not only are there no technical obstacles limiting the expansion of the CSAM system into additional forms of content, but primitive versions of the technology are used by many organizations and codified into most major industry security standards. For instance, a technology called Data Loss Prevention that also scans hashes of text, images, and files is already widely used in enterprise technology to identify a wide range of arbitrarily defined material.

If Apple holds its line and limits the use of client-side scanning to identify only CSAM and protect children from abuse, this move will likely be a footnote in the company’s history. But Apple will come under massive pressure from governments around the world to apply this on-device scanning technology to other content. Some of those governments are oppressive regimes in countries where Apple has already adjusted its typical privacy practices to be allowed to continue doing business. If Apple ever capitulates to any of those demands, this announcement will mark the end of Apple as a champion of privacy.