#1653: Apple Music Classical review, Authory service for writers, WWDC 2023 dates announced

At long last, Apple has released Apple Music Classical, a free app for Apple Music subscribers that seeks to address the challenges posed by classical music. Kirk McElhearn has written more about dealing with classical music on the Mac and iPhone than anyone, and he brings his decades of experience to reviewing Apple Music Classical. Do you publish on the Internet? Glenn Fleishman looks at Authory, a service that helps writers preserve a permanent record of their work and share it with their audience. Finally, Apple has announced dates for its Worldwide Developer Conference, where it will unveil the latest versions of its operating systems. Notable Mac app releases this week include CleanMyMac X 4.13, ScreenFlow 10.0.9, Transmit 5.9.2, Scrivener 3.3.1, and Pages 13, Numbers 13, and Keynote 13.

WWDC 2023 Scheduled for June 5–9

In an announcement that surprised approximately no one, Apple has scheduled its 2023 Worldwide Developer Conference for June 5th through 9th. WWDC will once again take place online for free, along with a special one-day event at Apple Park, accessible by lottery. Requests to attend must be submitted by 4 April 2023. Also on the docket is a Swift Student Challenge for budding developers, who have until 19 April 2023 to submit their entries.

It’s a safe bet that the WWDC keynote will feature iOS 17, iPadOS 17, macOS 14, watchOS 10, and tvOS 17. Plus, the rumor mill is working itself into a tizzy over Mark Gurman’s report of the possible unveiling of a mixed-reality headset. Other rumors from Gurman suggest a 15-inch MacBook Air, the long-awaited release of a Mac Pro with Apple silicon, and conceivably an M3-powered update to the 24-inch iMac, though that seems slated for later in the year.

This is also a good opportunity to remind everyone of our Apple-Related Conferences in 2023 collection—if you know of conferences that should be listed, add them!

Authory Provides Writers a Permanent Record of Their Articles

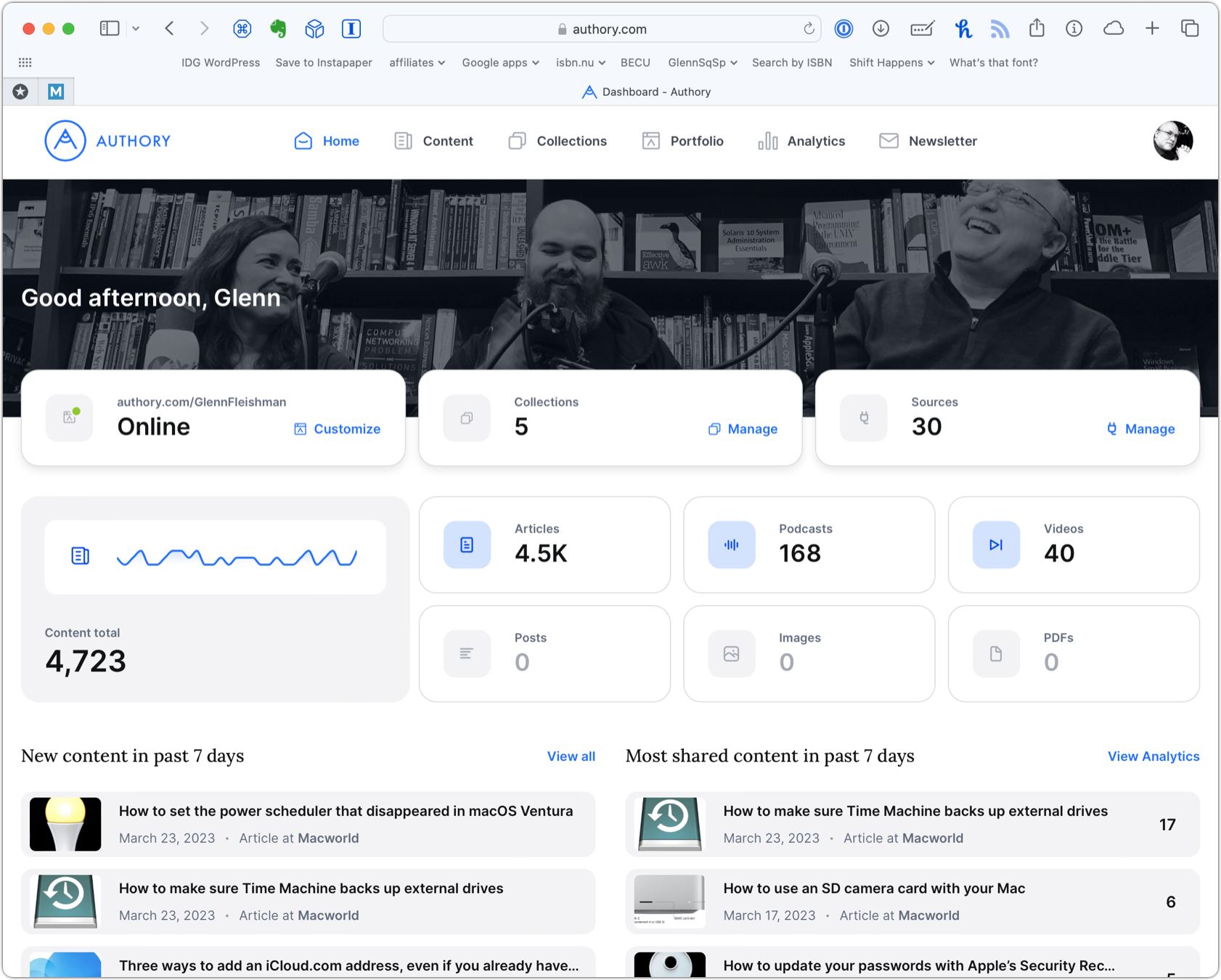

If you have published articles on the Internet for any length of time, either personally or professionally, you know how hard it is to maintain a coherent list of everything you’ve written. Worse, publications routinely change content management systems, rendering previous URLs obsolete, or shut down completely, taking their archives with them. I’ve lost access to numerous old articles, and it has happened to every writer I know. Whether you’re a freelance author, tech writer, college professor, or just someone who wants a record of your writing, the Authory service is worth a look. It provides a self-updating portfolio, a permanent archive, and an automatic newsletter of your new work for those who want to follow you.

Authory uses RSS feeds and site scraping to collect everything you’ve written in the past that’s still accessible and anything new as it’s published. The company creates a private full-text backup copy for you and exposes the text for public searching. It lets you maintain a permanent, unlimited archive while also making your work more easily accessible in one place.

You don’t need to be or consider yourself a professional writer to take advantage of Authory: you might find it useful if you publish text at any website that identifies the author of an item. All you need is to point Authory to a URL at a site at which you post. That URL can be specific, like an RSS feed that only includes articles you wrote or blog entries you posted, or general, pointing to an entire site—Authory figures out how to scrape your articles from it. Authory can catalog and archive podcasts, videos, and LinkedIn posts. It will even index your videos hosted on YouTube, but not download them.

Authory’s name may sound like entropy, but it’s the reverse. It fights the link rot that destroys Internet history. Link rot has plagued the Web from its earliest days: the first time someone made a change on a website—like moving an HTML file from one directory to another—without installing an automated redirection, that was the first link rot. By breaking the extant URL that pointed to the thing they moved, that person prevented all future visits to that URL from working. Link rot is so pervasive that I wrote my first article about it in 2000 for Adobe Magazine; that link rotted within a couple of years. (Ironically, a blog entry I posted in 2002 mentioning link rot points to another missing 2001 entry. I recovered that entry, posted it, and found that nearly all its outbound links were dead.)

The Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine provides a backstop for general link rot, archiving in bulk. But for those who write for commercial websites, the Internet Archive may not capture everything, as some for-fee publications impose paywalls and other limitations on search results. That’s where Authory comes in.

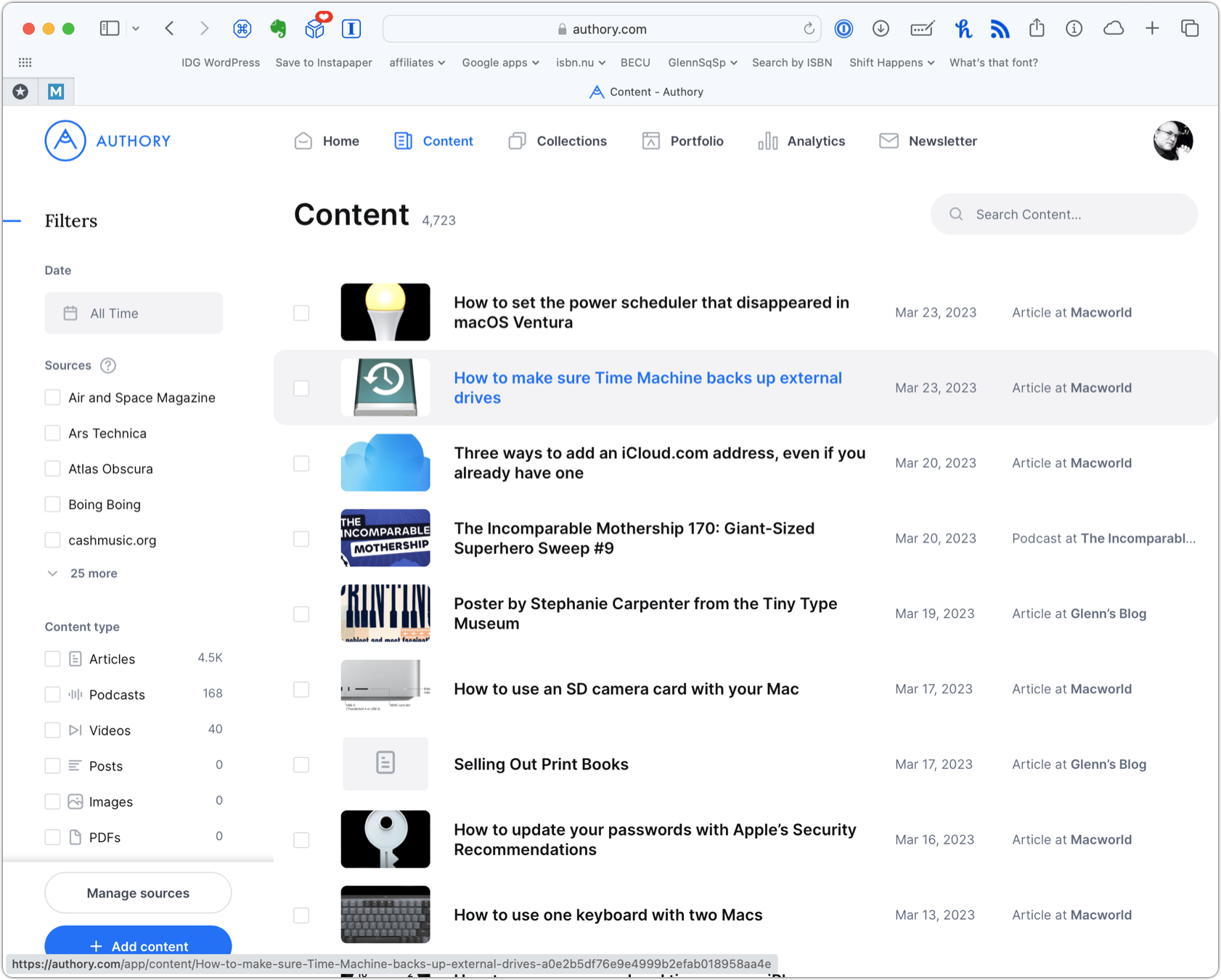

To populate Authory, you add sources, all the URLs that would contain your articles, podcasts, videos, or blog posts. When I started with Authory, it preferred RSS feeds but now doesn’t even recommend them when you’re setting up sources—the company does a lot of work behind the scenes to make sure your articles import from a site. You can also add specific links to your Twitter feed (as unfashionable as that seems at the moment), YouTube account, LinkedIn account, and podcast feeds. Authory automatically parses the feeds and other inputs for your name and alternative bylines you provide if you use different forms of your name. If articles or other content fails to import or be discovered, I have found Authory incredibly open to updating its parser.

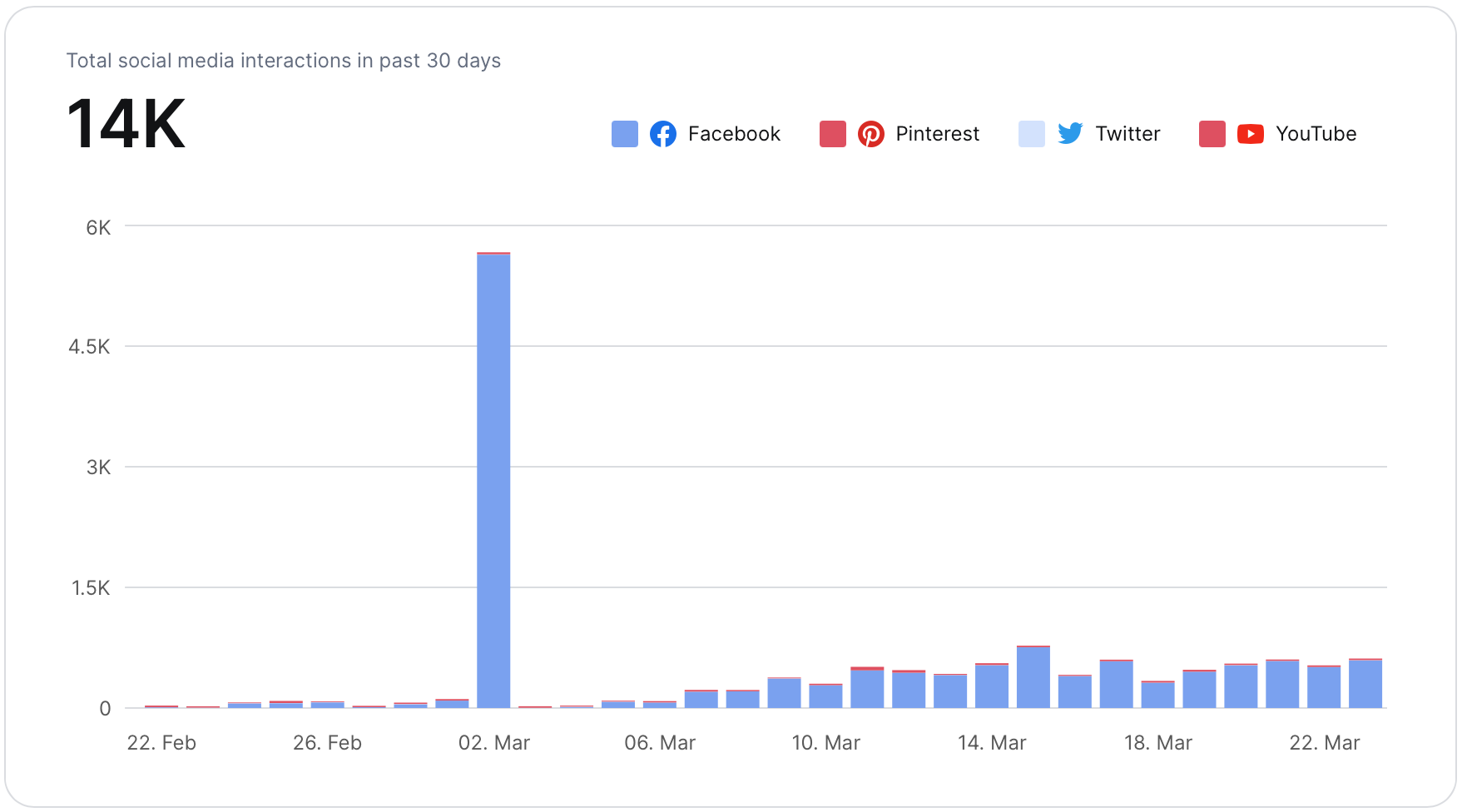

Once populated, Authory routinely scans for updates, like any RSS reader. As new articles come in, Authory adds the full text for articles to its database and updates your public page. It also downloads podcasts and retains the files. As Authory archives articles, it sends email to alert you. You also receive a summary of daily social-media interactions that it tracks by finding links to the original URL of the item extracted from an RSS feed. These stats appear as a chart on the site, too, revealing a bizarre spike for me that I tracked down to people sharing a 2018 article I’d written for Fortune about the presidential administration loosening train-safety regulations. That subject was briefly very popular.

Your account provides access to the full text of all articles and imported podcast audio. For posterity, you can at any time download your database as a set of HTML pages (one per article) or a massive XML file. On each article page, you can also opt to download a stripped-down view as a PDF. If link rot sets in at a particular website or publication, you’ve at least got your copy!

People who visit your Authory site can browse your work chronologically, search the full text of your stored articles and see a snippet in the results, and filter the results by publication or website, date range, and media type. Authory lets you create collections that appear on your public-facing page; I’ve made collections for what I consider my best articles of the year for 2018 through 2021. You can customize which collections appear, add a “portfolio cover” (a background image for the top of your page), and customize some text.

Visitors can also sign up for a newsletter that automatically emails them links to your new articles. In the spirit of the two-way hyperlink world, visitors can also subscribe to your Authory updates as an RSS feed.

When a user clicks one of your articles at Authory, it sends them to the originally archived URL by default. You can change this behavior in the source list, pointing people to the locally cached Authory copy. This is useful with publications or blogging platforms which no longer exist or provide access to your material. (Dozens of articles I wrote for the New York Times show up erratically in its search engine.)

At the moment, Authory doesn’t let you fix broken URLs directly, though you can email the support team to fix problems. It makes sense that an archive site wouldn’t want even its users to be able to edit the destination of a URL without some intermediation to preserve accuracy.

Authory has two tiers of service. Its Standard tier—which costs $15 per month or is discounted to $144 per year—requires that you enter sources and other links. You can create a customizable page on the Authory site for people to visit. Jump to the Professional tier ($24 per month or $216 annually), and Authory also automatically finds articles that mention you and any podcasts on which you’re a guest. (According to the company’s description, it doesn’t search blogs.) The Professional tier could be a worthwhile step up for folks who have syndicated content or receive regular coverage on news and other editorial sites. The Professional tier also lets you create a custom subdomain for your Authory content, supports automation with Zapier, and provides access to an API.

(In the spirit of full disclosure, I have paid for Authory since I started using it. However, I’m grandfathered into pricing from a few years ago and pay $70 a year for Standard. This lower rate wasn’t in exchange for anything, and I have no relationship with the company besides liking its service.)

Links break all the time: the original link to a Fast Company “Co.Design” article I wrote in 2018 about the Amazon Spheres has already rotted. After a reorganization, the fastcodesign.com domain redirects to a subsite at Fast Company, and all its links broke in the process. (My article is now on the main Fast Company site.) I flipped a switch in my Sources list at Authory, and now the article can be read in full at my profile.

(Are there copyright issues with this? Undoubtedly. But publications typically reserve exclusive rights for 90 days to 1 year, after which a writer has non-exclusive rights or full rights. Many publications also allow authors to post articles in their portfolios. Check your contracts and note that I am not a lawyer.)

Most importantly, my Amazon Spheres article remains available in my Authory account, along with hundreds of articles that are harder to find or no longer online. In all, Authory has stored 4723 articles for me that I no longer worry about evaporating into the ether.

It might be worth signing up for Authory just to create and download an archive of all your content, but its automatic article acquisition, portfolio presentation, and newsletter make it something that many writers, podcasters, and content creators will appreciate on an ongoing basis.

Apple Music Classical (Mostly) Plays the Right Chords

In the mid-2000s, I was approached by a tech entrepreneur who was a fan of classical music and had a foundation that supported many classical artists. He had contacted me because of articles I had written for Macworld about iTunes and classical music. At the time, my classical library already contained thousands of ripped CDs, and I was one of the few people writing about using iTunes with classical music. He was frustrated at the state of metadata available for classical music, provided by Gracenote, which iTunes used to populate metadata when you ripped CDs. (Metadata is the information about the CD and its tracks: the album name, artist, track names, etc.) He wanted to fund a free database of classical music so people could rip CDs and get the right metadata for tracks in their iTunes libraries and other apps.

This was a mammoth task. Among much else, it would have involved developing a list of canonical names for composers (do you use Johann Sebastian Bach, J. S. Bach, or Bach, Johann Sebastian?) and works (do you use Piano Sonata No. 14 in C-sharp minor or the more commonly used Moonlight Sonata for Beethoven’s work?). Normalization would ensure that no composer or work would be split in the database and allow multiple language versions. However, since even record labels didn’t agree on naming conventions, you couldn’t just use what was on a CD but would have to adapt the listings to the database. One idea was to use the Grove Music Dictionary as a standard to determine canonical naming conventions. This database would make it possible to have consistency across recordings.

Unfortunately, after a year of exploratory work, a financial shock depleted the patron’s foundation, causing the project to be abandoned. To this day, there is no standard database of recordings that can be used to ensure metadata integrity.

I tell this story because it shows how difficult it is to set up a service enabling users to catalog and search for classical music. But without such a catalog, classical music fans have been forced to put square metadata into CD-shaped holes, starting with the earliest days of iTunes.

The free Apple Classical Music app, released on 28 March 2023 for Apple Music subscribers, shows that Apple understands at least part of the problem. It’s a huge step forward. While many aspects of the classical music experience still don’t quite fit into those round holes, Apple Music Classical shows that Apple is trying and is committed to supporting classical music in the future.

How You Listen to Music

Think about how you choose music to listen to. The simplest example is the jukebox. You see a number of songs, together with the names of the artists who perform them. You insert a coin, pick a song, press the buttons, and listen. With LPs or CDs, you flip through a stack of records, find one you want to listen to, and start playing it. The three variables—song, artist, and album—are the main search criteria you use when looking for music to play.

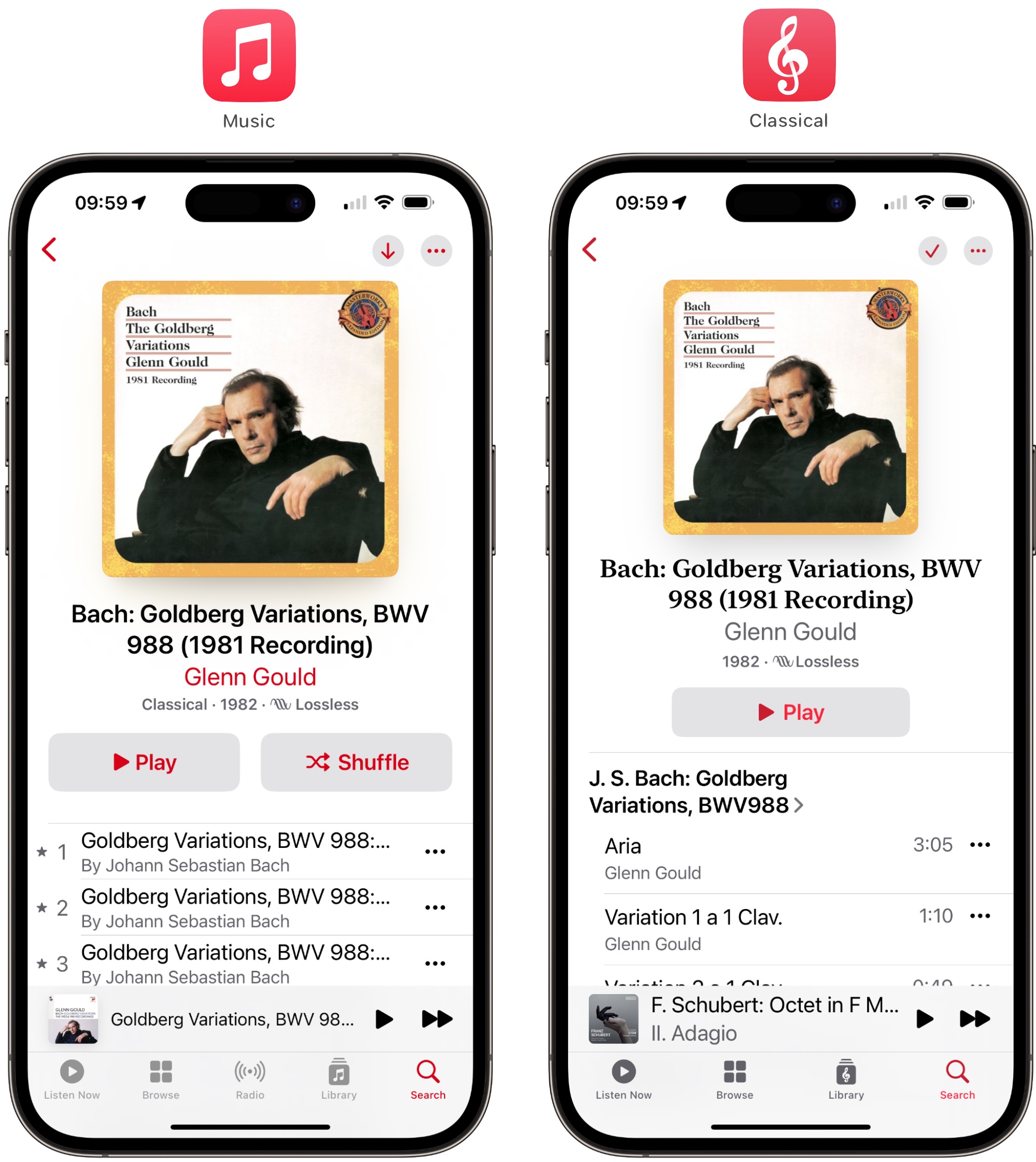

Classical music is much more complex. While you may look for a specific piece of music or a favorite album, you often look to play a work, which could be a piano sonata, an opera, a string quartet, or a symphony. You won’t find any of them on the jukebox, and if you were to flip through a stack of records, their titles might or might not help you find what you want. For some album-length works, this isn’t complicated. If you want to play Glenn Gould’s recording of Bach’s Goldberg Variations, that’s easy to find. It takes up an entire album, and you will see a picture of Glenn Gould on the cover.

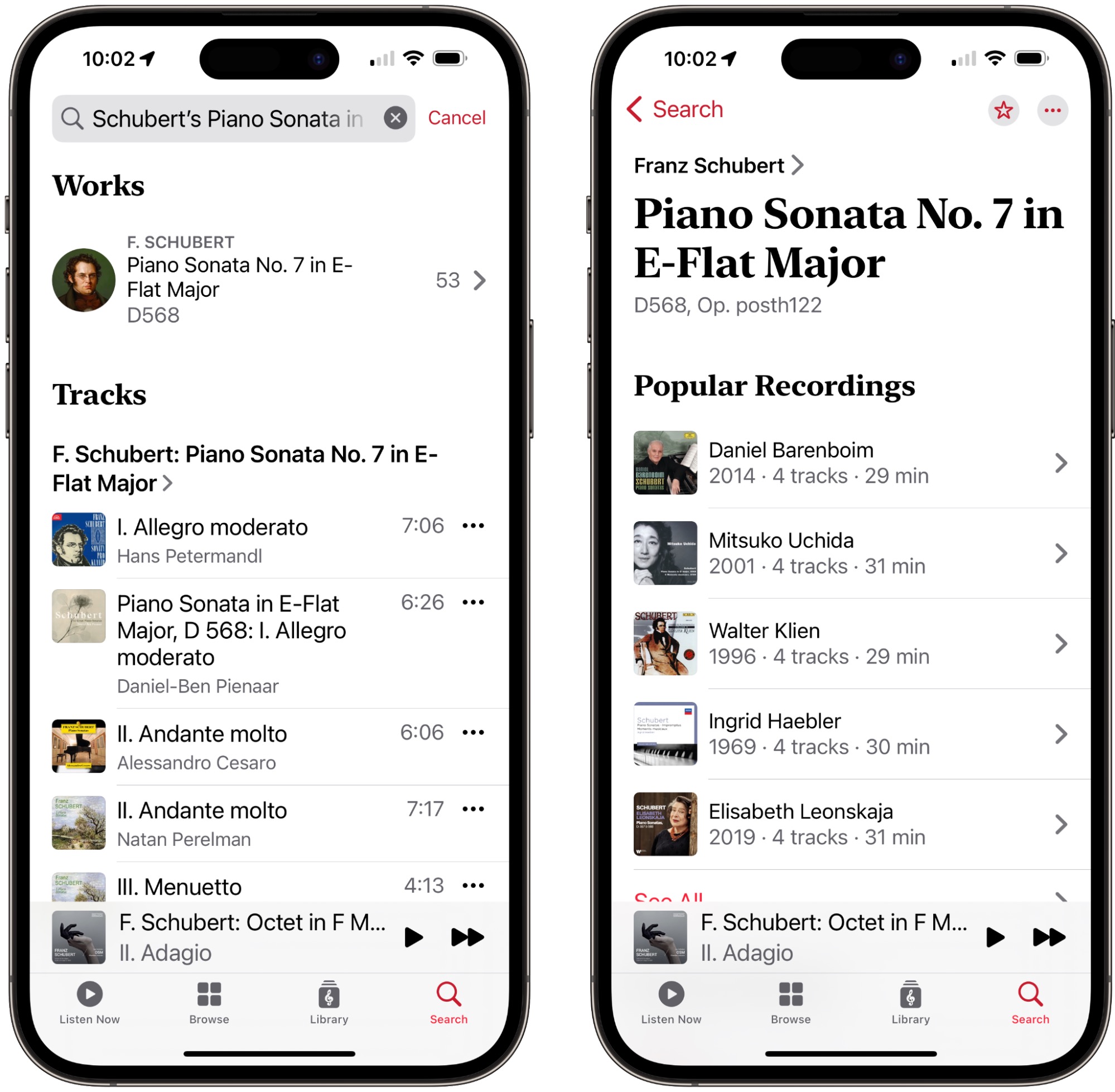

It’s a bit more difficult to find Schubert’s Piano Sonata in E-flat major D 568. At about 30 minutes long, it doesn’t take up an entire CD, and most recordings of it contain one or two other piano sonatas. In addition, you may want to listen to an interpretation by a specific pianist among the dozens who have recorded this sonata. The Presto Music website shows 44 recordings, and it’s not an exhaustive list. (I choose this specific work as an example because it is fairly widely recorded but not among Schubert’s most popular sonatas.)

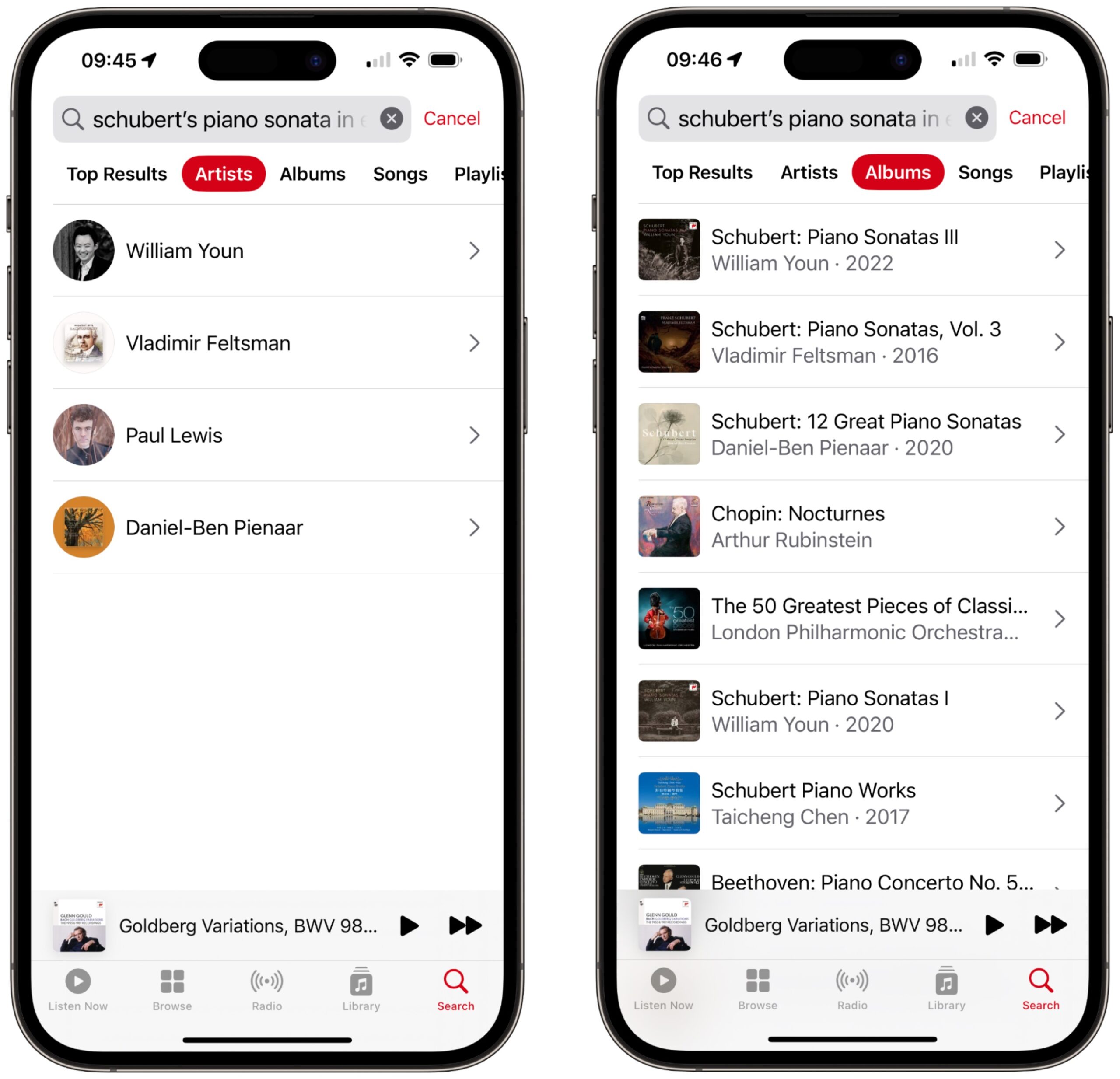

Compare that list to a search I did in the Apple Music app. As you can see (below left), it found only four artists. When I switched to album search results (below right), Apple Music showed me three albums before swerving to an Amazon-like list of recordings, many of which have nothing to do with Schubert’s sonata, such as Nocturnes by Chopin and piano concertos by Beethoven and Mozart.

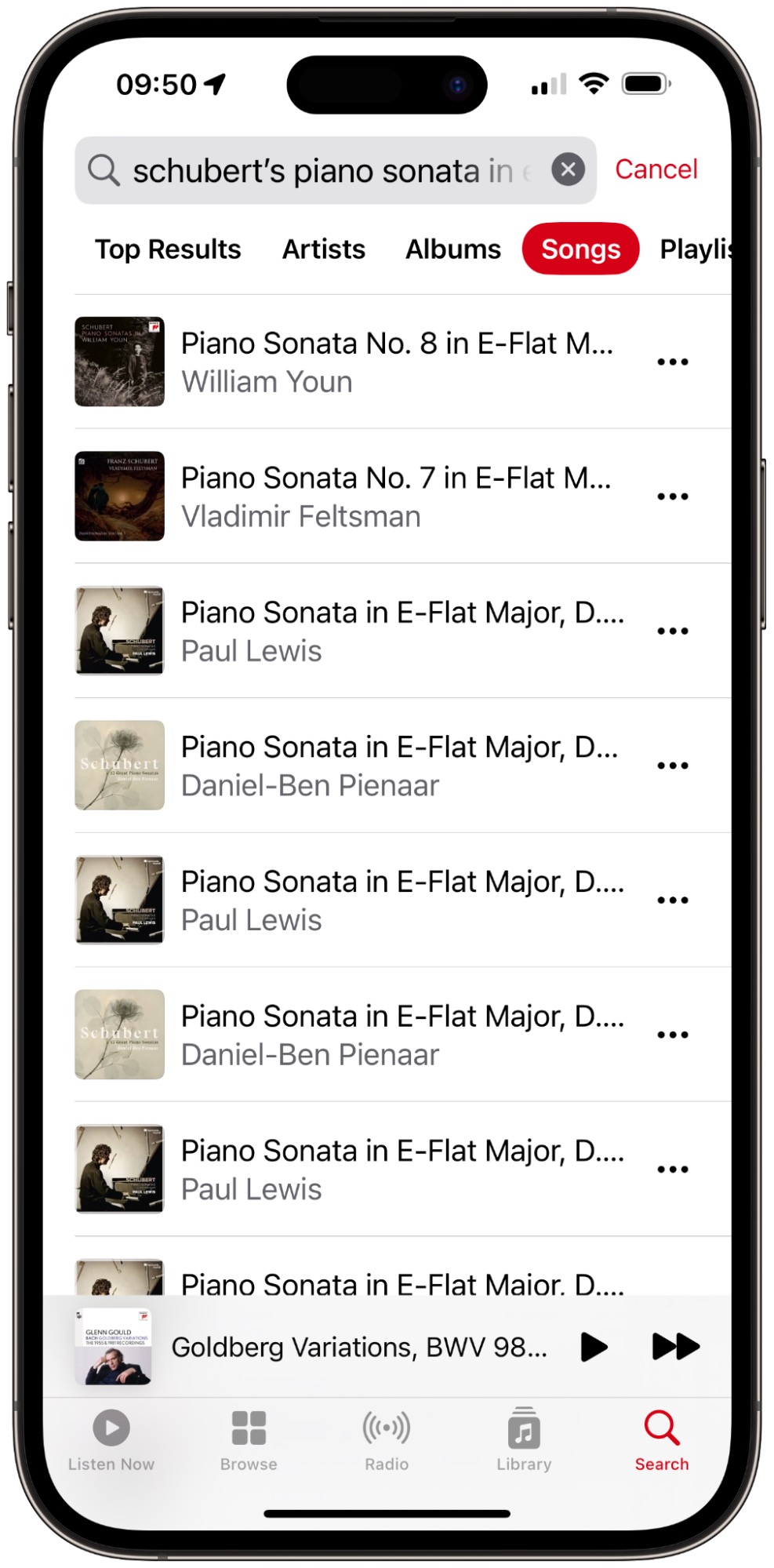

The search results for “songs”—which these tracks are not, but that’s another problem with streaming music terminology—show the four movements of the work by a few pianists and, when I scroll down, drift off toward random piano works.

William Youn is a young pianist, just starting out on his career. Vladimir Feltsman is much older but not well known. Paul Lewis is a well-known interpreter of Schubert, and his recording is recent. Daniel-Ben Pienaar is less well-known, and his 2020 recording is on a small label. Where are the great recordings of this work by Mitsuko Uchida, András Schiff, or Alfred Brendel? Why do I not see the classic recording by Wilhelm Kempff, one of the first pianists to record most of Schubert’s piano sonatas and an example of the Germanic tradition of romantic piano music? Where is Paul Badura-Skoda, who recorded all of Schubert’s sonatas on original instruments, pianofortes from the 19th century? What about Daniel Barenboim, who recorded all of Schubert’s piano sonatas in 2014 on a specially constructed piano?

No, Apple showed me just a few artists and a bunch of albums that did not contain the sonata I searched for.

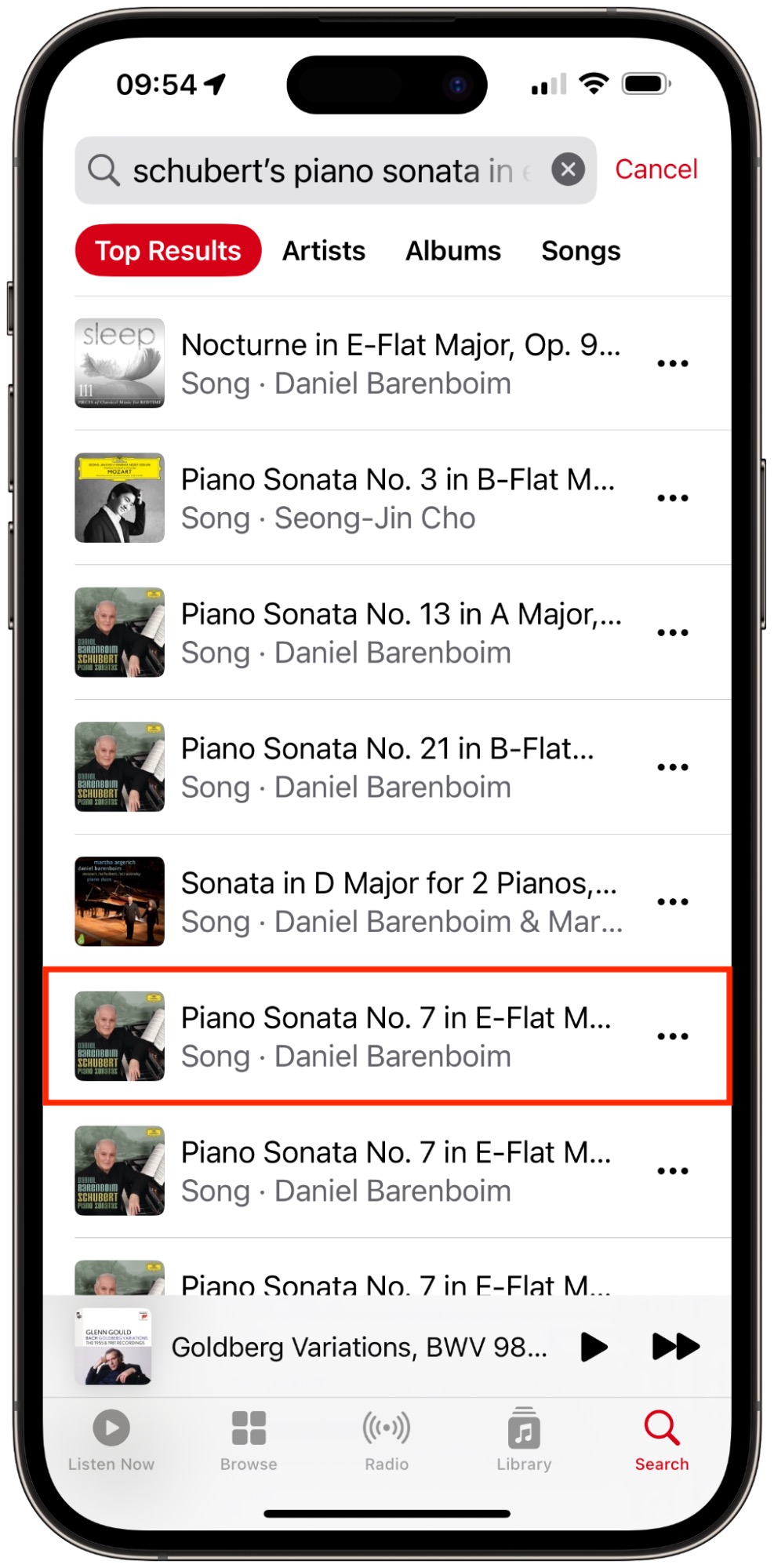

What if I refined the search and tried to find the recent recording by Daniel Barenboim? I added Barenboim to my search, and here’s what Apple showed me. His Schubert recording is the sixth in the list, after several recordings by other artists and composers. At the top of the list is a Chopin Nocturne played by Daniel Barenboim; Apple seems to want to push Chopin to Schubert fans.

Due to the way classical works have been cataloged over time, many of their names are unique, at least for the most famous composers. Schubert’s compositions are cataloged according to the work of Otto Erich Deutsch, hence the D before work numbers. Bach’s works have BWV numbers, for Bach-Werke-Verzeichnis, or Bach works catalog. For other composers, opus numbers are used, referring to a specific publication. So for Beethoven, we have Op. 26: Piano Sonata No. 12 in A♭ major, which is a single piano sonata, and Op. 27, which contains two piano sonatas, No. 1: Piano Sonata No. 13 in E♭ major, and No. 2: Piano Sonata No. 14 in C♯ minor, also known as the Moonlight Sonata.

The point of this somewhat lengthy preamble is to explain why searching for classical music is so much more complicated than searching for popular music. You may want to listen to a specific work by a given composer, but also by one of your favorite performers. And, as you can see with the example of the Schubert sonata, work names are not always as simple as Bach’s Goldberg Variations. Metadata is the key to managing classical music.

Apple Music Classical Improves Metadata

When Apple added the Work and Movement tags to iTunes 12.5 back in 2016, the company showed the first signs that it might finally be interested in classical music. Those tags enable you to manage multi-movement works, tagging them together, and they are useful for search.

Apple’s biggest task in preparing for the release of the Apple Music Classical app was to update the tags on potentially millions of tracks. (Apple claims that its library contains “over 5 million tracks.”) Browsing through classical albums on Apple Music in recent years, it was clear that some labels provided excellent metadata with work and movement tags, and that the major labels had started using these tags in recent years, but that much catalog music—older recordings, which are often the cornerstones of a classical collection—were all over the map.

Updating this metadata undoubtedly involved a lot of grunt work, and it’s probably why Apple failed to release the Apple Music Classical app by the end of 2022, as originally promised. Apple needed to identify which tracks were classical and ensure that they were tagged correctly and consistently despite the poor metadata often provided by record labels.

When you first launch the Apple Music Classical app, if you already have classical music in your Apple Music library, you’ll find all that music in the Albums section of the Library tab. Or will you? Alas, Apple Music Classical, as its name implies, works only with music hosted in Apple Music, not CDs that you’ve ripped or downloads that you’ve purchased from sources other than Apple, even if they are labeled with the Classical genre.

In my Apple Music library on a secondary Mac, the Classical genre contains over 25,000 tracks across more than 1,200 albums. Many albums don’t appear in Apple Music Classical because I had ripped them from CDs or purchased them separately. (My iMac holds my main library, which has some 30,000 tracks ripped from CD; I don’t sync this library with Apple Music because I don’t trust Apple not to alter its metadata.)

Most of the albums in my library that are on Apple Music show up in the Apple Music Classical app. A few are missing, and it’s hard to know why. I’ve found a few albums that lack work and movement tags, so perhaps Apple is filtering out albums with insufficient metadata.

However, I also find albums by:

- Harold Budd, a pianist whose music could sound classical but is not

- Brian Eno, whose ambient music is certainly not classical, and whose song albums, such as Another Green World, are as rock as they can be

- Nils Frahm, a contemporary pianist whose work might, at a stretch, be called classical crossover

- Jazz ensemble Nik Bärtch’s Ronin, which is, well, jazz

- Wim Mertens, another contemporary composer whose music could, at a stretch, be called classical but whose recordings are not generally found in the classical bins at record stores

- Robert Fripp, whose music is about as far from classical as could be

- And even Ornette Coleman, whose free jazz is definitely not classical.

I could go on. I suspect that Apple is trying to group together some music—Budd, Frahm, Mertens—that people who don’t know classical music might think is classical, but I can’t explain what Apple is doing for the other artists.

Introducing the Apple Music Classical App

Apple Music Classical is a free app for Apple Music subscribers to access this new, enhanced collection of music. Inexplicably, it is only available for the iPhone. One would expect Apple Music Classical to be available for desktop computers, especially since many people listen to classical music from a Mac, or a PC running iTunes, connected to a stereo. Since Apple Music has added a lot of high-resolution music, which requires an external DAC (digital-analog converter) to play at its full quality, it is quite difficult to play that sort of music from an iPhone. You can stream music to an AirPlay 2-compatible receiver with a DAC attached, but most people don’t have that hardware. You can, of course, stream Apple Music Classical from an iPhone to a HomePod—the second generation of which also supports Dolby Atmos, or what Apple calls spatial audio—but overall, this focus on the iPhone limits playback options considerably.

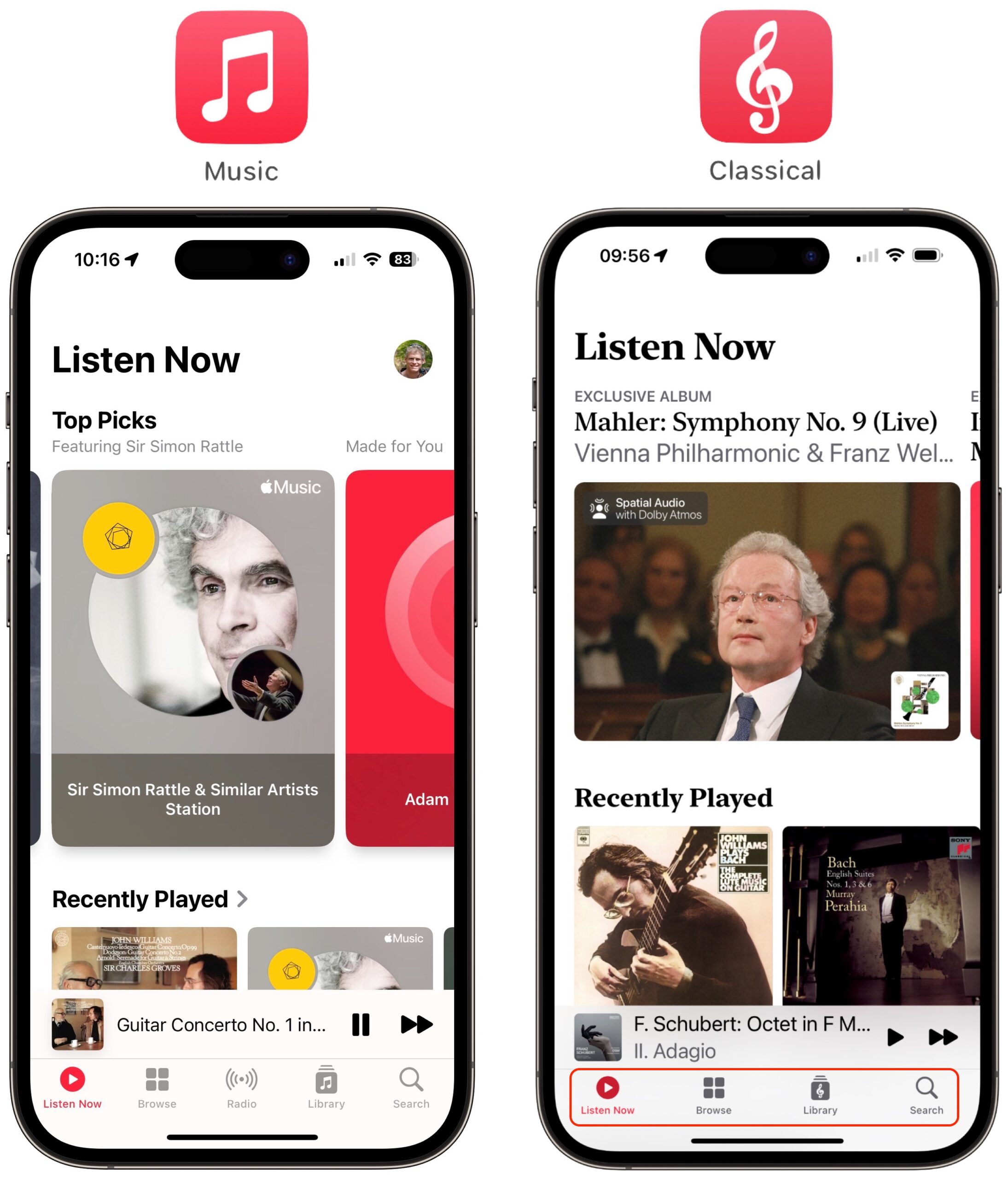

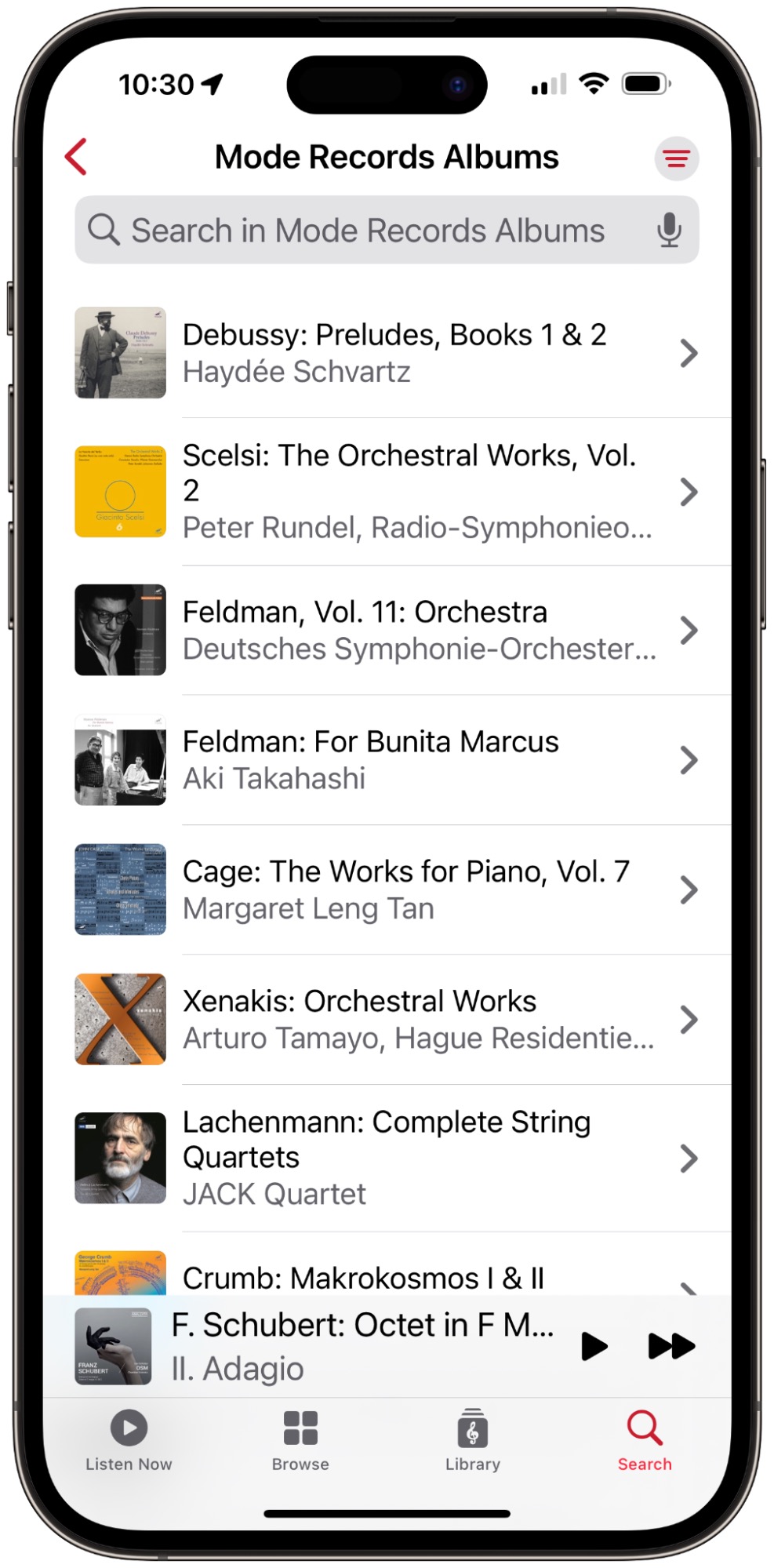

The Apple Music Classical app (below right) is extremely similar to the Apple Music app (below left), with a clef on its icon instead of two beamed quavers and a nearly identical interface.

The toolbar icons on the bottom offer the following options:

- Listen Now is similar to the identically named feature on Apple Music. You see featured content, recently played albums, and various thematic sections. At launch, these include Periods and Genres, Exclusive Albums, New Releases, Now in Spatial Audio, The Story of Classical, and more.

- Browse gives you access to the entire Apple Music Classical library. You can browse the catalog by composers, periods, genres, conductors, and more; you can browse playlists; and you can search by instrument.

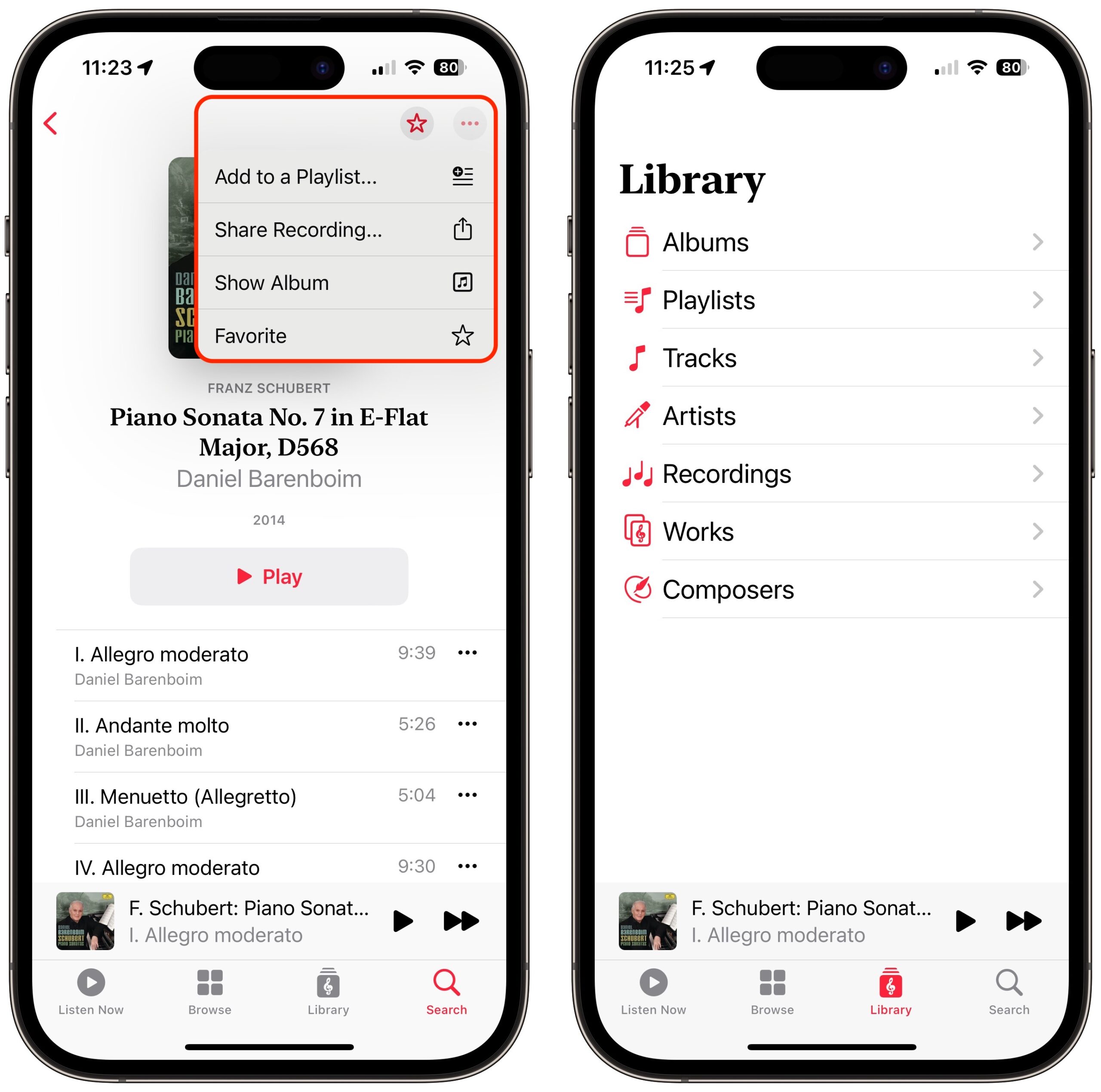

- Library shows all the music in your Apple Music Classical library. If you have already added classical music to your Apple Music library, it will display here. (Though some albums labeled as classical in my Apple Music library don’t appear here.) Anything you add from the Apple Music service also displays here.

- Search lets you search for works, albums, composers, artists, and more.

For the most part, you use the Apple Music Classical app just as you would use the Apple Music app, though one tab is missing: Radio. For now, Apple Music Classical does not have any radio stations for classical music—even though Apple Music does contain several such stations—and does not allow you to create a custom “radio station” based on a track or album. Nor can you download music to listen offline, though when you add albums to your library, they also get added to your Apple Music library, so you can download them in the Apple Music app and listen to them there.

Who Is Apple Music Classical For?

Two types of people will want to use Apple Music Classical. Those who don’t know much about classical music but want to explore it, and those who are already classical music fans and want to find their favorite artists and recordings and discover new ones.

If you fall into the former category and want to discover classical music, browsing the Listen Now section will help you discover different types of music. Apple has provided a number of playlists with spoken introductions in The Story of Classical, a nine-part selection of music. If you want to learn more about different classical periods (baroque, romantic, etc.), The Story of Classical will help.

However, I’ve always felt that the belief that people need to be educated about classical music creates a barrier to listening and makes the music seem elitist. If you are new to classical music, I recommend listening to the music before the spoken-word content so you can feel the music before hearing the lectures. You would get a lot more from listening to a playlist of Bach’s music than a dry, public-radio-style program telling about the history of how he composed and the technical aspects of his music.

You can explore Composer Essentials playlists to get a feel for the many well-known composers highlighted in Apple Music Classical. The problem is that they play individual movements rather than entire works, and, while they give you a sense of a composer’s style, they mix up disparate works. Beethoven’s symphonies are very different from his piano sonatas and string quartets, yet all these and more appear in the same playlist. You may like the big symphonic sound, or you may be more seduced by his virtuosic piano compositions or sinuous string quartets, but lumping it all together—in a 12-hour playlist!—doesn’t seem like a good way to get to know Beethoven’s music.

Many people think that classical music is just for relaxation. (They clearly haven’t heard Mahler’s symphonies or Wagner’s operas.) Apple caters to this misconception with Music by Mood playlists, with titles such as Classical Sleep, Late Night Classical, Relaxing Classical, Classical Concentration, and Piano Chill. If this is your jam, feel free to explore such playlists, but I also encourage you to explore music by composers whose tunes resonate with you.

Searching for Classical Music

As I explained above, accurate metadata is the biggest hurdle to getting classical music streaming right. All of the albums I have looked at so far feature work and movement tags, which are essential not only for searching, but also for listening. Here are two screenshots: on the left is the Apple Music app, in which you can see that there’s no way to discern the name of each track; on the right is the Apple Music Classical app, which displays the work name on the top, in bold, and the movement names below, all visible.

Continuing with my previous example, I searched Apple Music Classical for Schubert’s Piano Sonata in E-flat major D 568. (When I searched for just “D 568,” it displayed the same thing.) The results were much better than in Apple Music. You can see that the work itself is identified; tap its name to see 53 recordings of it.

Popular Recordings lists five albums recorded by well-known artists; scroll down and tap See All to see all results. When you tap a result, you see the work you searched for, and only that work. You can scroll down and tap Featured On to see the full album containing that work.

When viewing a work, tap the more (•••) icon and select Add to a Playlist to save the work or add it to an existing playlist in your library. Tap Share Recording to send a link to a friend. Tap Show Album to see the entire album the work is from. Or tap Favorite to assign it a star. The Favorite star is the classical equivalent of the Love option for Apple Music. You can favorite Recordings, Works, Composers, and Artists, and they display in the various sub-sections of the Library screen.

When viewing an album, tapping + at the top of the screen adds the album to your library. It displays in the Albums entry of the Library screen, and it also gets added to your Apple Music library, so you can access it from the Apple Music app as well. However, favorite recordings, works, composers, and artists are not added to your Apple Music library.

Note that adding an album to your library doesn’t add it to the Recordings list. That section displays recordings—that is, works by specific artists, which may or may not be entire albums—that you have favorited. This can be a good way to bookmark recordings without adding them to your library and cluttering it up.

One useful feature is the ability to search within search results. After you’ve searched for something, pull down on the screen to reveal a search field. You can enter keywords in this field to further narrow your search. You can also access this search field in other lists. For example, go to Browse, tap Instruments, then tap Violin. Tap one of the options—Latest Releases, Popular Artists, or Popular Works—and you’ll see a list of results. Pull down, and you can search within that list.

Unfortunately, this sub-search field is not available when you view the Albums list in your Library. That list loads very slowly—about a dozen albums at a time when you scroll down—making it nearly useless for finding music to listen to. Because of this, it’s a good idea to favorite recordings you want to listen to, since you can search the Recordings list.

You can also sort and filter searches. Tap the filter icon at the top right of the screen, and choose to sort by Popularity, Title, or Release date. If you tap Filter By, you can choose Genre (orchestral, vocal, etc.), Period (medieval, baroque, romantic, etc.), and Instrument. The options for each of these are contextual; you won’t find the medieval option, for example, when searching a 20th-century composer or a record label with no music from that period.

With classical music, some labels specialize in certain repertoire and feature recordings from certain artists, and you may want to see what they have to offer. To help you focus your listening, Apple Music Classical enables you to browse content from specific record labels. While you can’t yet search for record labels, you will find links on album pages to labels. Scroll down to the Record Label section, then tap the name to see what a label has to offer.

Problems with Search

Search is not without its problems. For example, I searched for Morton Feldman and found that his most popular work is “Piano,” with 23 recordings. Tapping through the recordings of this work, I found works entitled “Piano, Violin, Viola, Cello,” “Piano Piece 1952 (Version 2),” “Extensions 1 for Violin and Piano,” “3 Clarinets, Cello & Piano,” and the one piece that he wrote that is, indeed, just titled “Piano.”

When I searched for albums of works by Toru Takemitsu, the Latest Albums list was unhelpful. You can sort some searches by tapping the filter icon at the top right of the screen, and when I sorted by Popularity, only one of the nine albums on the first screen contained Takemitsu’s name as a composer. All the other albums contained only one work by him, and I had to scroll to find albums where he was the only composer.

If someone wants to discover music by a composer they are unfamiliar with, there should be some editorial curation. In the case of Takemitsu, for instance, there are several excellent recordings of his work on the Deutsche Grammophon and Bis labels, in a series of albums dedicated to the composer.

Finally, Apple hasn’t fully normalized composer names. As you look through the Apple Music Classical app, you’ll see that there is a standardization, developed about 15 years ago, of having a composer’s name listed before a colon at the beginning of an album or work title. Yet I find albums listed under both Cage and John Cage, Bach and J.S. Bach, and Dowland and John Dowland. Far too few albums even respect this standardization, making it hard to weed through long lists of albums.

Where Do We Go from Here?

The most perplexing thing about the Apple Music Classical app is how completely it is siloed. It’s only available for the iPhone, though you can install it on an iPad and zoom it to 2x. Not only is it not available on the Mac—the iPhone app isn’t even available for M-series Macs—but the enhanced metadata, using work and movement tags, is not visible in Apple Music on the Mac nor in the Apple Music app on the iPhone and iPad. It seems Apple is using two separate databases, which makes no sense. If the metadata is available—and work and movement tags are available on many albums in Apple Music already—why not let the other apps access them?

It also seems like it should be trivial to add Apple Music Classical to the Music app on the desktop. Adding a sidebar entry would not change the interface much, and since all of the content in the Apple Music Classical app is HTML, the Music app would have no problem displaying it. It’s the exact same type of content that Apple Music uses.

All this makes the Apple Music Classical app seem like an experiment. It’s quite polished for a 1.0 release, and, despite the issues that I’ve mentioned above that will irritate classical music fans, it’s a generally successful attempt to provide a better way to access classical music. Apple should be praised for paying so much attention to a genre that represents only 2–3% of the overall music market.

I’ve long complained about the way iTunes, then the Music app and Apple Music, have dealt with classical music. The earliest such articles I can find on Macworld date back to 2005. In Corral your classical music, I wrote, “If you’re a fan of classical music, then you’ve probably, at some point, become frustrated with iTunes and the iPod. Track information from the Web is inconsistent, pieces are difficult to tag and categorize, and imported songs don’t flow seamlessly into one another.”

I’m happy to say that Apple has finally solved many of these problems. It’s a shame that it took so long.