#1658: Rapid Security Responses, NYPD and industry standard AirTag news, Apple’s Q2 2023 financials

Apple has released its first Rapid Security Responses, updates to iOS, iPadOS, and macOS meant to address security vulnerabilities more quickly than would be possible with full updates. Adam Engst explains what’s involved and why you can install them without worry. Michael Cohen looks at Apple’s Q2 2023 financial results, which were down slightly from the year-ago quarter, largely due to unfavorable exchange rates. Glenn Fleishman explores two bits of AirTag news: the New York Police Department’s recommendation of AirTags to aid in car theft recovery and the announcement by Apple and Google of a draft industry standard for making it easier for people to detect unwanted trackers. Finally, we share links to a pair of welcome lists: one providing uses of the Option key and another enumerating all macOS updates for the past few years. Notable Mac app releases this week include only GraphicConverter 12.0.2.

What Are Rapid Security Responses and Why Are They Important?

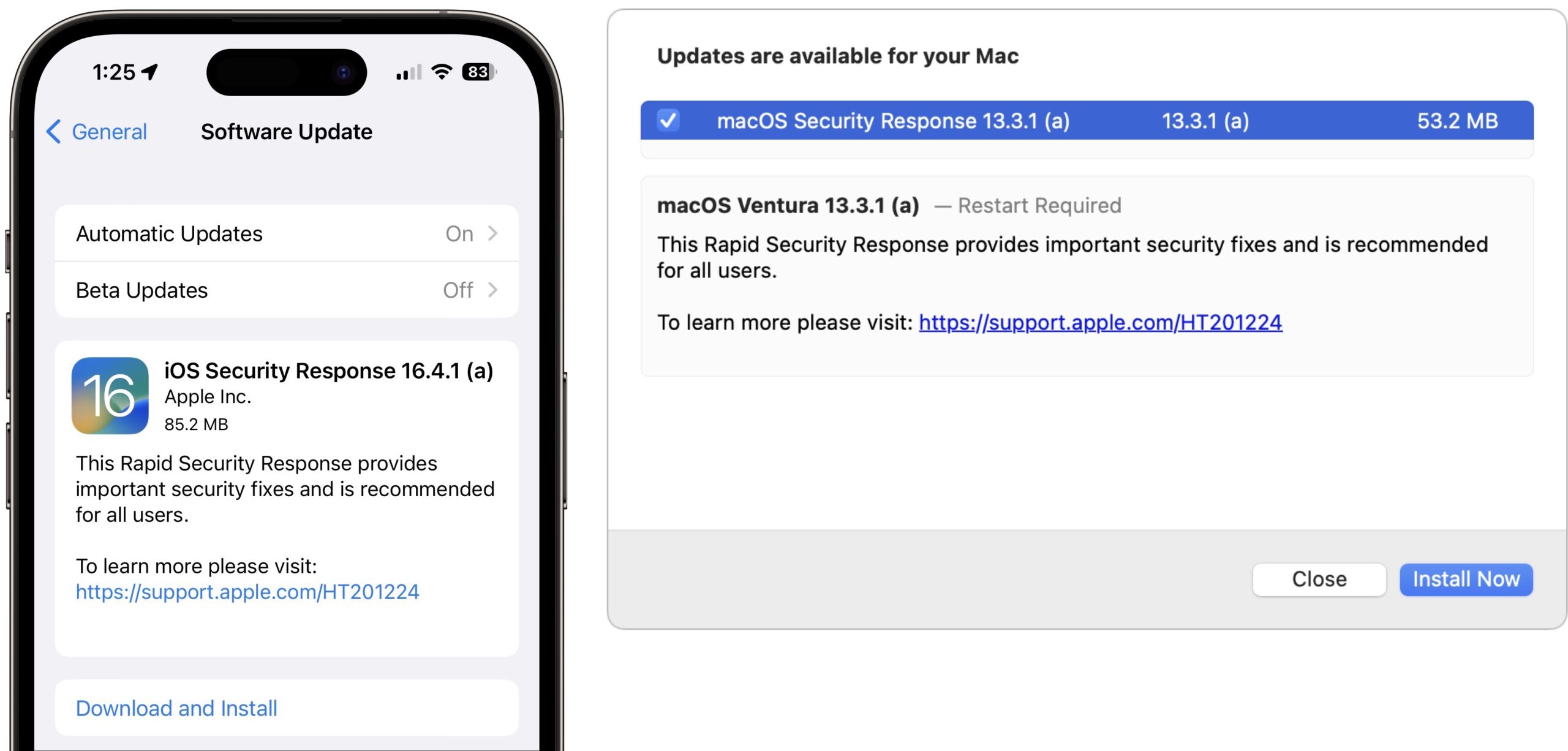

One of Apple’s promised features for iOS 16, iPadOS 16, and macOS 13 Ventura was a new type of update, the Rapid Security Response. The first of these updates have now shipped, so you can update to iOS 16.4.1 (a), iPadOS 16.4.1 (a), and macOS 13.3.1 (a) in Software Update. Apple hasn’t said what security vulnerabilities these updates address on either the Apple Security Updates page or the release note pages for iOS 16, iPadOS 16, and macOS 13, but realistically, the vast majority of users don’t care about such tweaky technical details. I’ve updated all three operating systems with no problems, and I encourage you to update as well.

So what’s a Rapid Security Response, and why are we seeing them now? Apple’s goal is to distribute important security fixes to users more quickly and encourage faster adoption, particularly when a vulnerability is being exploited in the wild. Although only Apple knows how long it takes for its user base to install security updates, it’s undoubtedly slowed by three factors:

- Download size: Although high-speed Internet connections are commonplace, many people still have slower connections that cause them to delay large updates.

- Installation time: More problematic is the downtime associated with installing an operating system update. We all schedule updates for when life circumstances permit.

- Update hesitancy: Some updates have introduced new problems, causing cautious users to delay updating until early adopters have reported success.

The first two factors stem from Apple’s move to the read-only Signed System Volume in macOS 11 Big Sur. As the inimitable Howard Oakley explains, changing the contents of the Signed System Volume requires installing the update on the System volume, making a cryptographically sealed snapshot, and restarting from that snapshot. Because of the many files that require updating for even minor changes, updates require large downloads and lengthy installation times.

Apple’s solution is to move components likely to need updating—Safari and its underlying WebKit foremost among them—outside of the Signed System Volume. That makes them easier to update but also more vulnerable. To maintain security for such external components, Apple introduced special disk images called cryptexes (cryptographically signed extensions). There’s almost no documentation of cryptexes apart from Howard Oakley’s exploration, where he says they’re stored on the Preboot volume and loaded early in the boot process, when they’re grafted into the parent file system such that their contents effectively become part of the system.

Rapid Security Response updates are also cryptexes, which theoretically allows them to be a fraction of the size of traditional security updates, and they should install in vastly less time, addressing the first two factors that delay update adoption.

Installing Rapid Security Responses

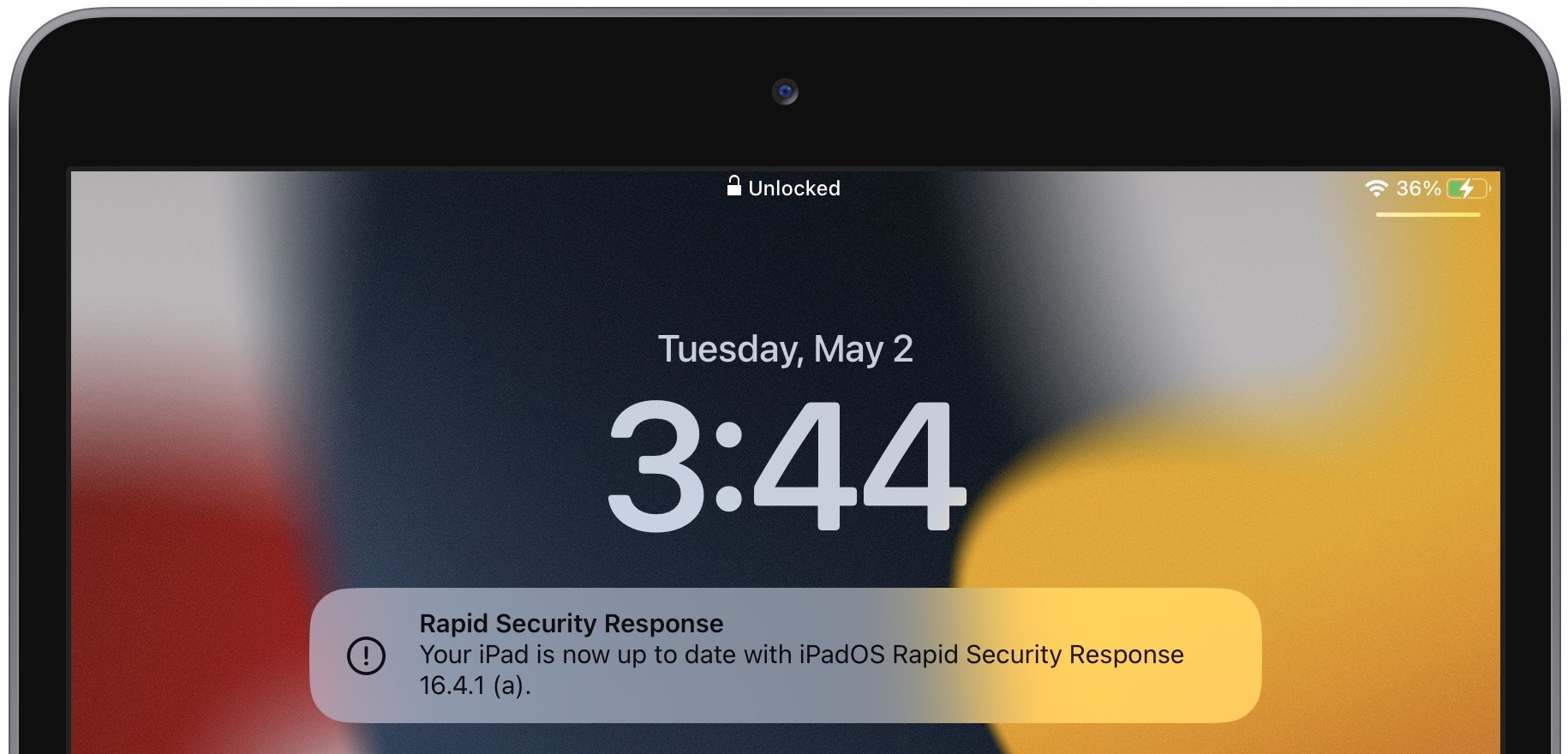

By default, all iPhones, iPads, and Macs running the latest operating systems allow Rapid Security Responses to be applied automatically. Theoretically, you shouldn’t notice them being installed unless a restart is required, which was true of all three of these updates. After restarting, iOS and iPadOS—but not macOS—posted a notification alerting the user to the update. I suspect Rapid Security Responses that don’t warrant restarts will also generate such notifications.

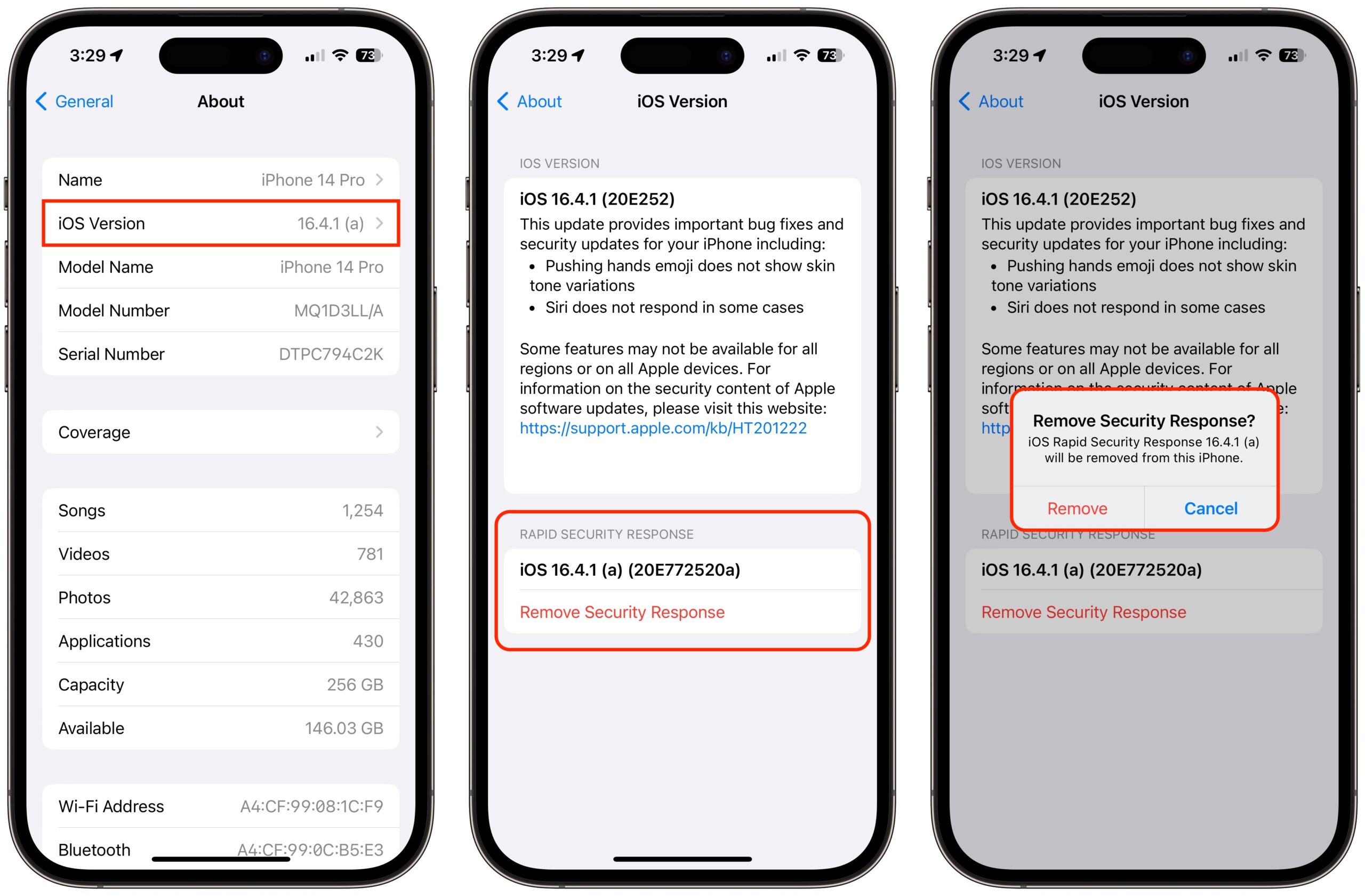

You can always tell if a Rapid Security Response has been installed because the version number in Settings > General > About or About This Mac will include a letter, as in iOS 16.4.1 (a). I presume Apple will increment the letter if multiple Rapid Security Responses ship before the next operating system update.

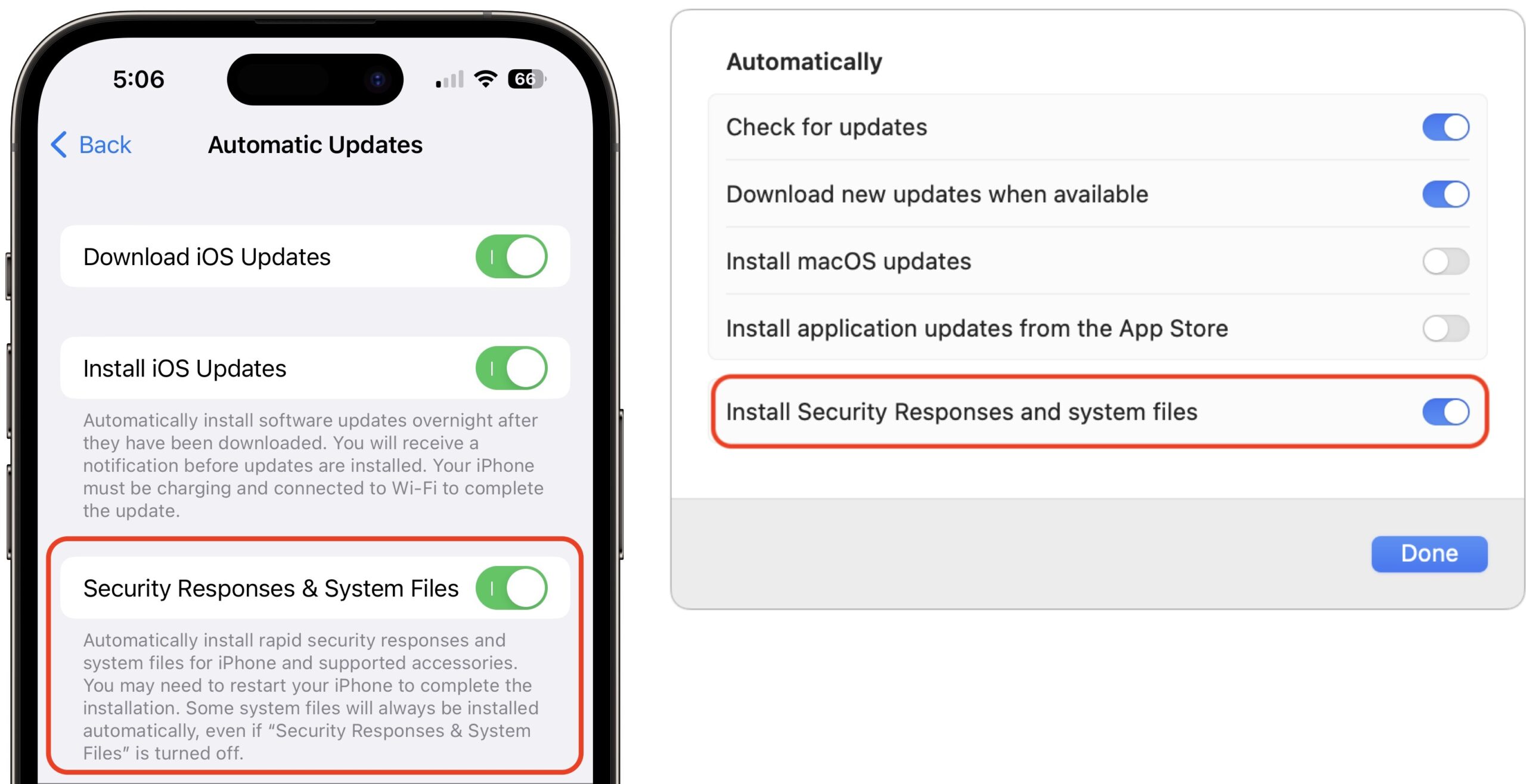

You can check to make sure Rapid Security Responses are set to be installed in:

- iOS/iPadOS: Go to Settings > General > Software Update > Automatic Updates, and look at “Security Responses & System Files.”

- macOS: Go to System Settings > General > Software Update, and click the ⓘ next to Automatic Updates. Then look at “Install Security Responses and system files.”

If you turn off automatic updates or avoid installing Rapid Security Responses when they become available, you’ll automatically get all the included fixes with the next operating system update. I plan to allow mine to install automatically, and I encourage most other people to do so, too. If you want full manual control, that’s fine, but then it’s your responsibility to check for and install updates. Given the small downloads, quick installation, and ease of reverting, I think it’s worth letting Apple work to protect our devices against attack as it sees fit.

On my devices, the updates ranged in size from 53.2 MB to 309.8 MB, and the installation time was commensurate with the update size and power of the machine. Apple has clearly solved the size and time problems.

| Device | Update Size | Installation Time |

| iPhone 14 Pro | 85.2 MB | 4 minutes |

| 10.5-inch iPad Pro | 86.2 MB | 13 minutes |

| 27-inch iMac | 53.2 MB | 1.5 minutes |

| M1 MacBook Air | 309.8 MB | 4 minutes |

What about update hesitancy? Since the entire point of Rapid Security Responses is that Apple can push them out quickly, presumably with less testing time than a full operating system update would require, it’s more likely that they could have unanticipated side effects. But since cryptexes are atomic—they’re standalone disk images whose contents are grafted into the system at boot—it’s easy for Apple to provide a mechanism for removing them. So if you experience apps crashing or other significant problems immediately after installing a Rapid Security Response, you can remove it and revert to the previous version of the operating system. That’s a huge win and something that’s never before been possible.

Removing Rapid Security Responses

In iOS and iPadOS, you remove a Rapid Security Response by going to Settings > General > About > iOS/iPadOS Version, tapping Remove Security Response, and confirming the action. Removing the Rapid Security Response from the iPad Pro was roughly the same speed as installing—about 14 minutes—but after it restarted, the update was available to install again, as it should be.

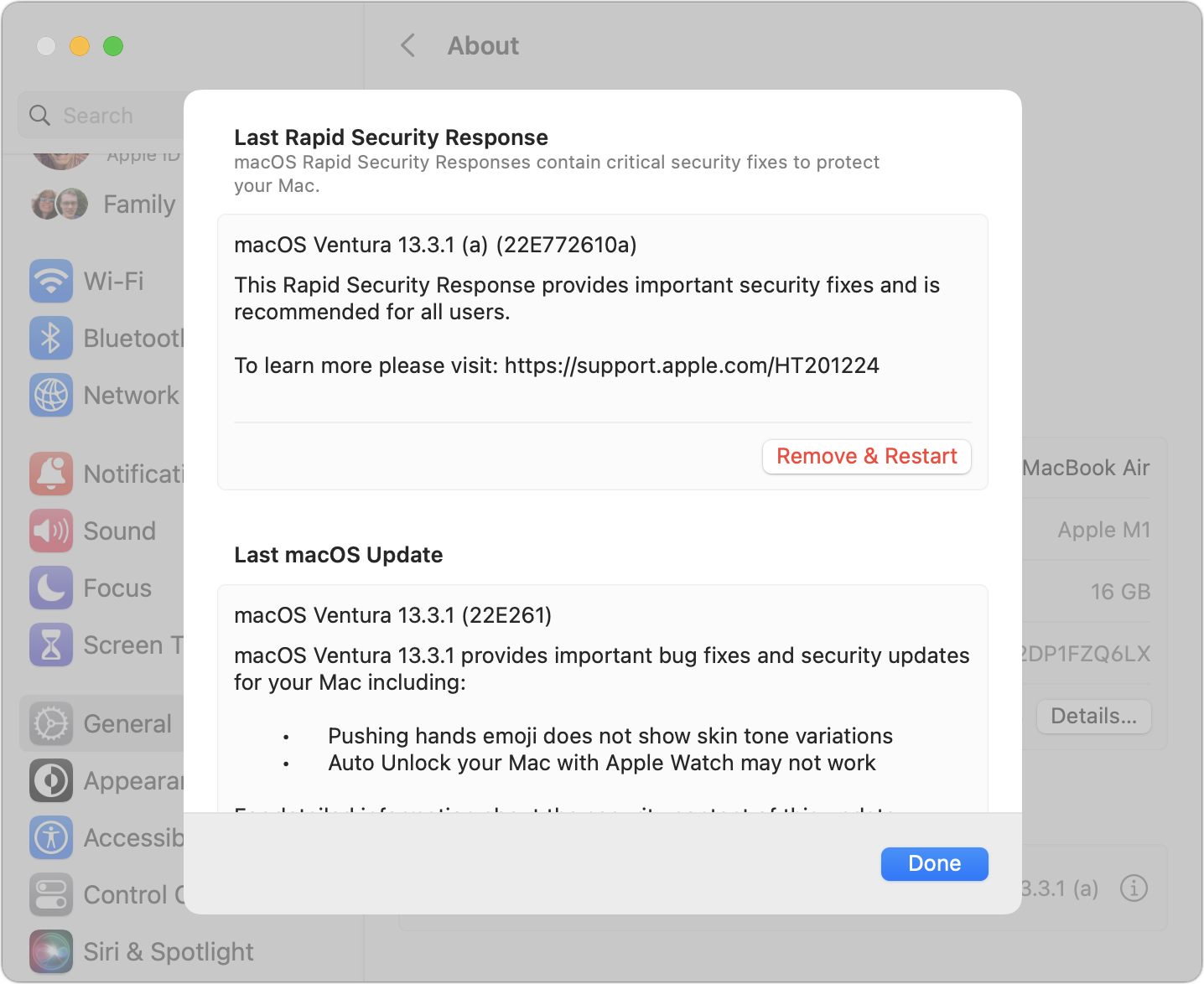

On the Mac, removing a Rapid Security Response requires going to System Settings > General > About, clicking the ⓘ next to the macOS version, clicking Remove & Restart, and confirming the action. The process took about 2.5 minutes. On the first boot after removing, Software Update wouldn’t show me the Rapid Security Response, claiming that macOS 13.3.1 was up to date. After another restart, it came back, and I was able to reinstall it.

Note that the release notes of the previous operating system update also appeared on these screens. That’s a small but welcome addition.

Ultimately, it’s good to see Apple finally utilizing the long-promised Rapid Security Response update mechanism. I’ll admit that I had somewhat come to dread operating system updates, particularly on the Mac, where you can end up staring at a black screen for far longer than is comfortable. Rapid Security Responses won’t fix that problem for actual operating system updates, but I hope Apple can use them to reduce the number of full updates that are necessary.

Apple’s Q2 2023 Slightly Down on Exchange Rates and “Macroeconomic Conditions”

Reporting on its second fiscal quarter of 2023, Apple announced profits of $24.2 billion ($1.52 per diluted share) on revenues of $94.8 billion. The company’s revenues were down 3% compared to the year-ago quarter, with profits per share essentially unchanged year over year (see “Apple’s Q2 2022 Results Help Brighten Dark Times,” 28 April 2022).

In their conference call with financial analysts, Apple CEO Tim Cook and CFO Luca Maestri said the results were in line with expectations, laying the blame for the slight year-over-year revenue decline on “headwinds” created by foreign exchange and “macroeconomic conditions,” a vague term that covers productivity, interest rates, inflation, employment, and global events. Maestri pointed out that foreign exchange headwinds had a 5% impact on revenues, suggesting that Apple would have posted a 2% gain without exchange rate issues. He also said the results for the next financial quarter would be similar to those in the quarter just ended.

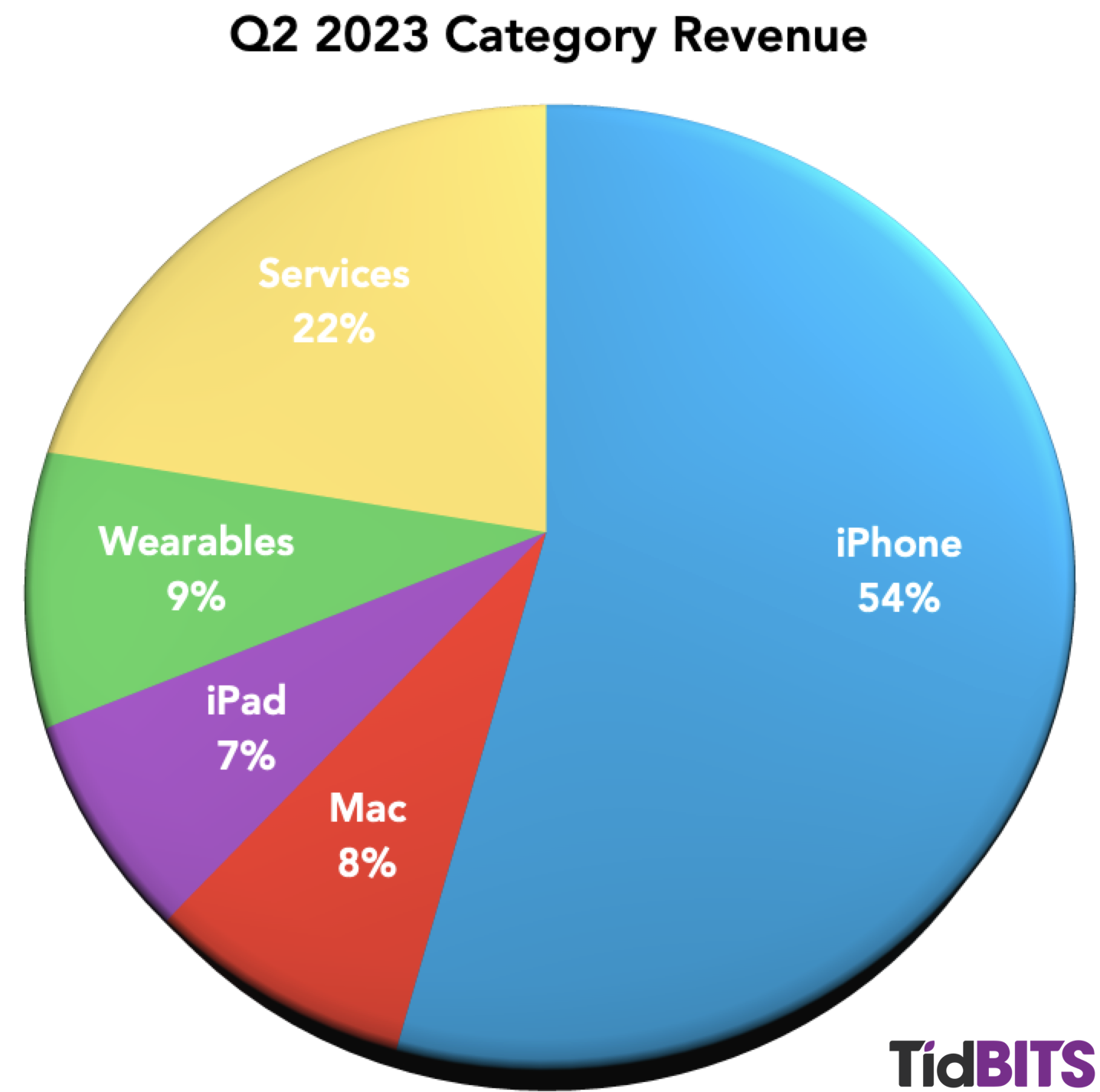

The bright spots in Apple’s quarter were the iPhone, which set a Q2 record, and Services, which set an all-time revenue record. Together, they accounted for 76% of Apple’s revenues. On the other side of the equation, the Mac and the iPad dropped noticeably from the year-ago quarter, and Wearables remained essentially flat.

iPhone

Apple saw its iPhone revenues rise slightly, to $51.3 billion from last year’s $50.6 billion, an increase of about 2%. In his opening remarks, Cook called out the cameras in the iPhone 14 lineup as one of the drivers for the increase. Whatever the reason, the small uptick in iPhone revenues helped bolster Apple’s overall quarterly results.

Mac

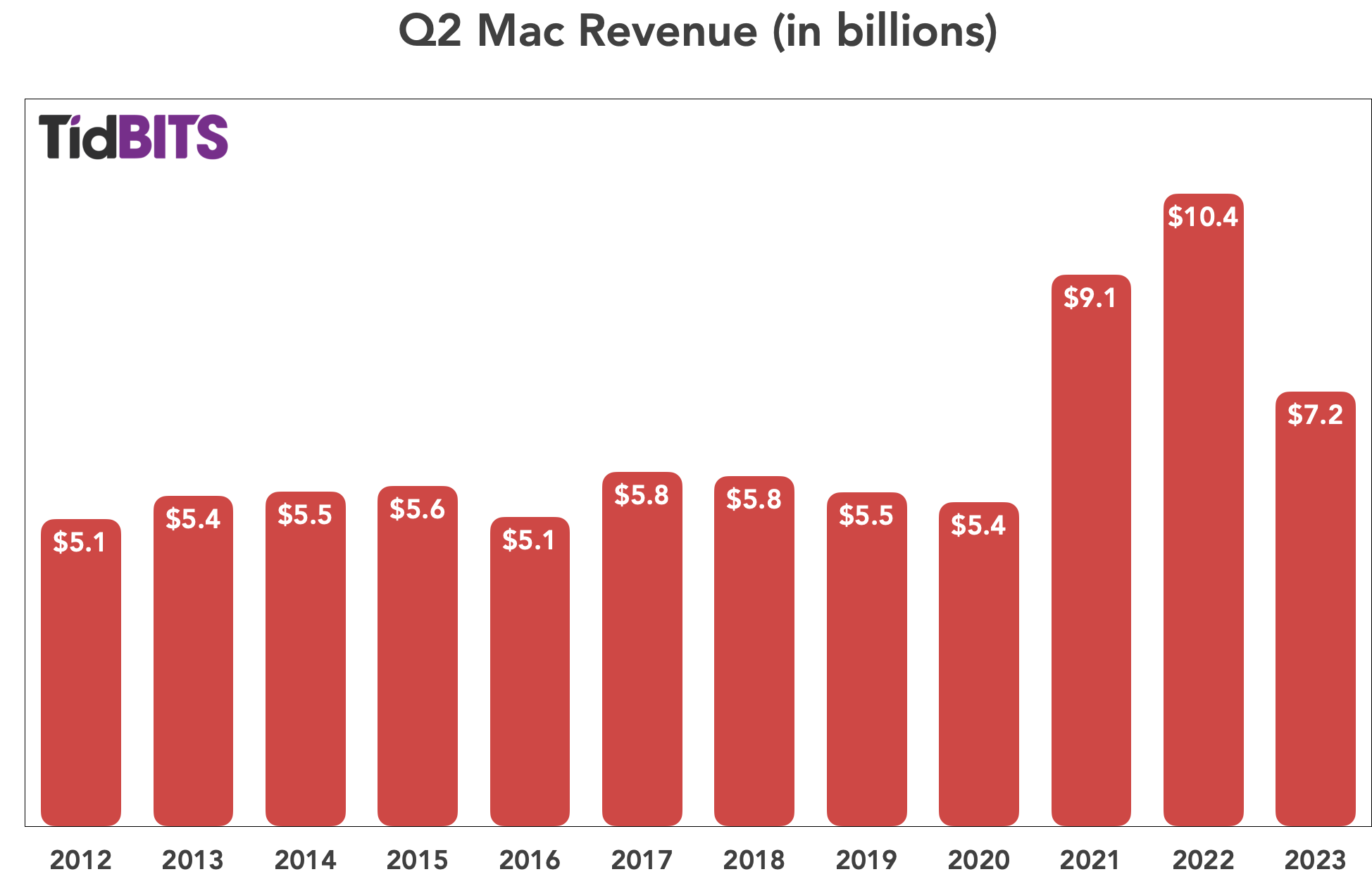

The phrase “tough compare” came up frequently regarding Apple’s Mac sales for the quarter. Those sales dropped over 30% from the same quarter last year, achieving just $7.2 billion in revenue compared to $10.4 billion. Last year saw the rollout of the M1 chip throughout the Mac lineup, which dramatically spurred sales, while this year’s releases weren’t as ground-breaking. Even still, Mac sales were well above any year prior to 2021, which was boosted by the introduction of the M1 chip and people working and learning from home during the pandemic (see “Apple’s Jaw-Dropping Q2 2021 by the Numbers,” 28 April 2021).

iPad

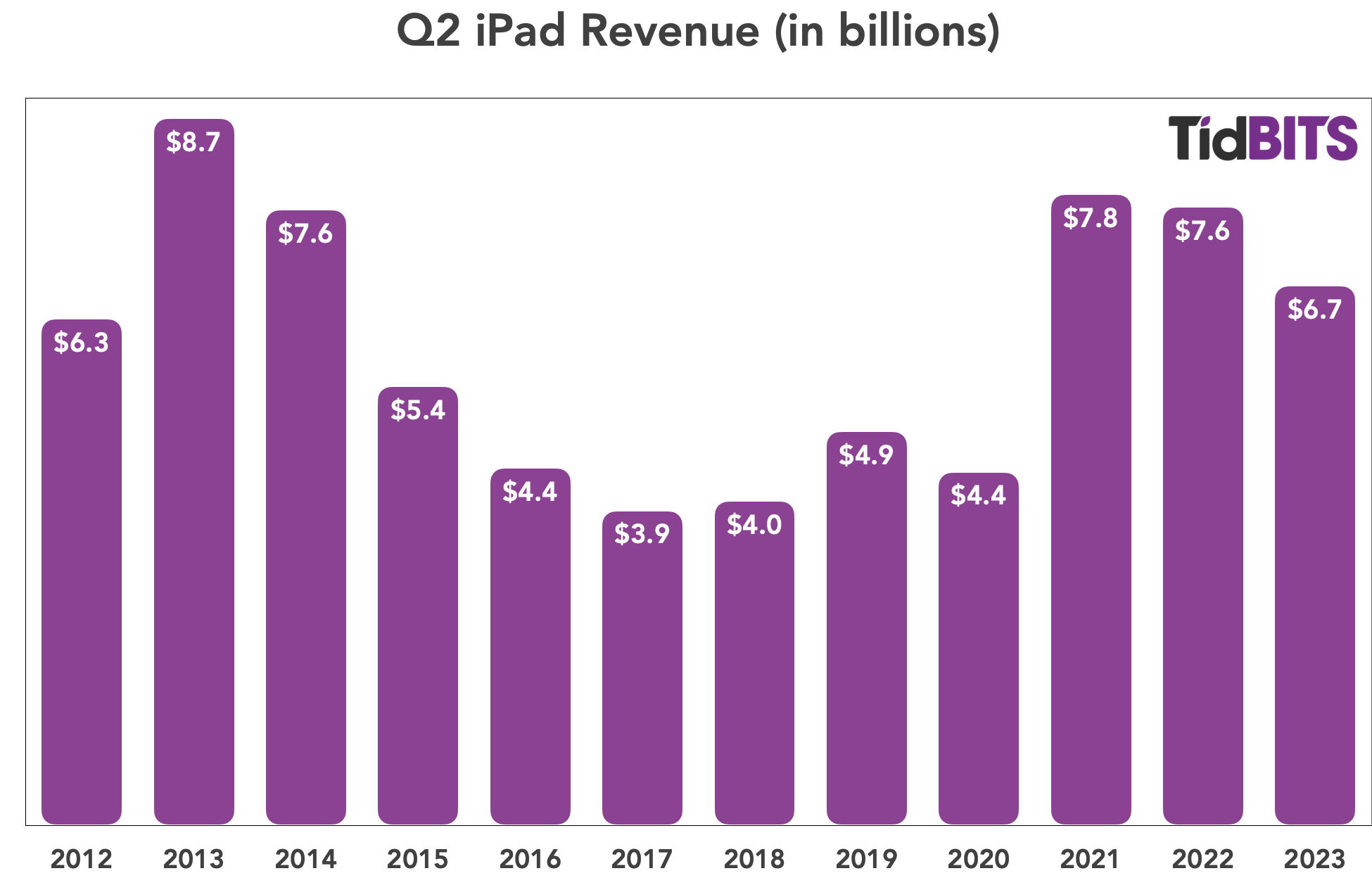

Like the Mac, iPad sales also suffered a year-over-year sales downturn, bringing in $6.7 billion as opposed to last year’s $7.6 billion. Cook said Apple expected these results for similar reasons as the Mac slowdown: last year saw the introduction of the M1-based iPad Air, compared to no such release this year. Maestri attributed the quarter’s 13% reduction in iPad revenues to the “macroeconomic environment.” Still, compared to the 6 years before the pandemic, Apple didn’t do badly.

Wearables

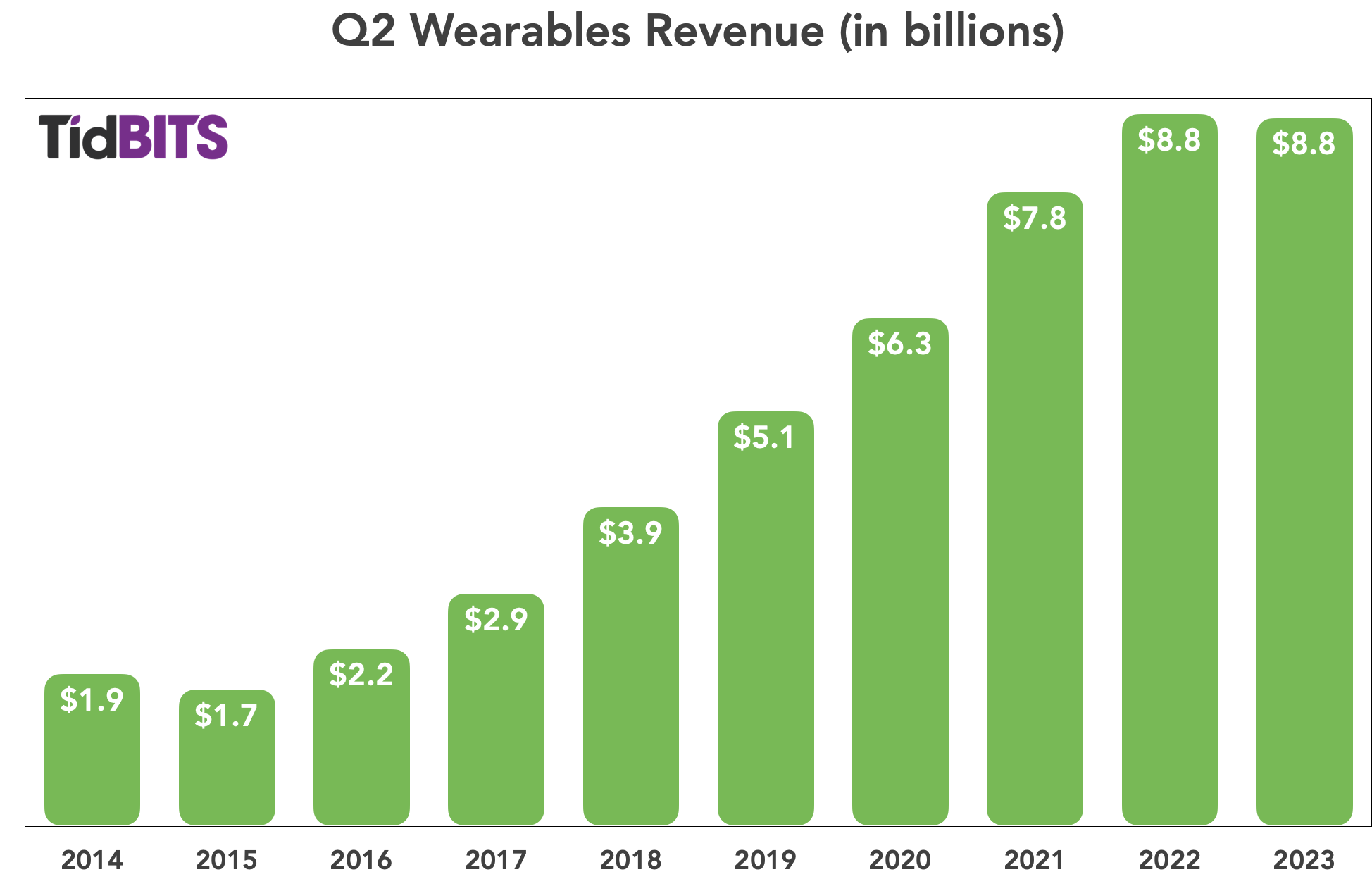

Falling in at the end of the parade of revenue declines, Apple’s income from its Wearables, Home, and Accessories business suffered a tiny year-over-year drop of less than 1%, with $8.76 billion in sales compared to the year-ago quarter’s $8.81 billion. Cook gave no reason for these flat results, while Maestri again trotted out the macroeconomic environment as the primary cause. Maestri did point out that two-thirds of Apple Watch purchasers in the quarter were new to the product, implying the likelihood of healthy future sales of that device.

Services

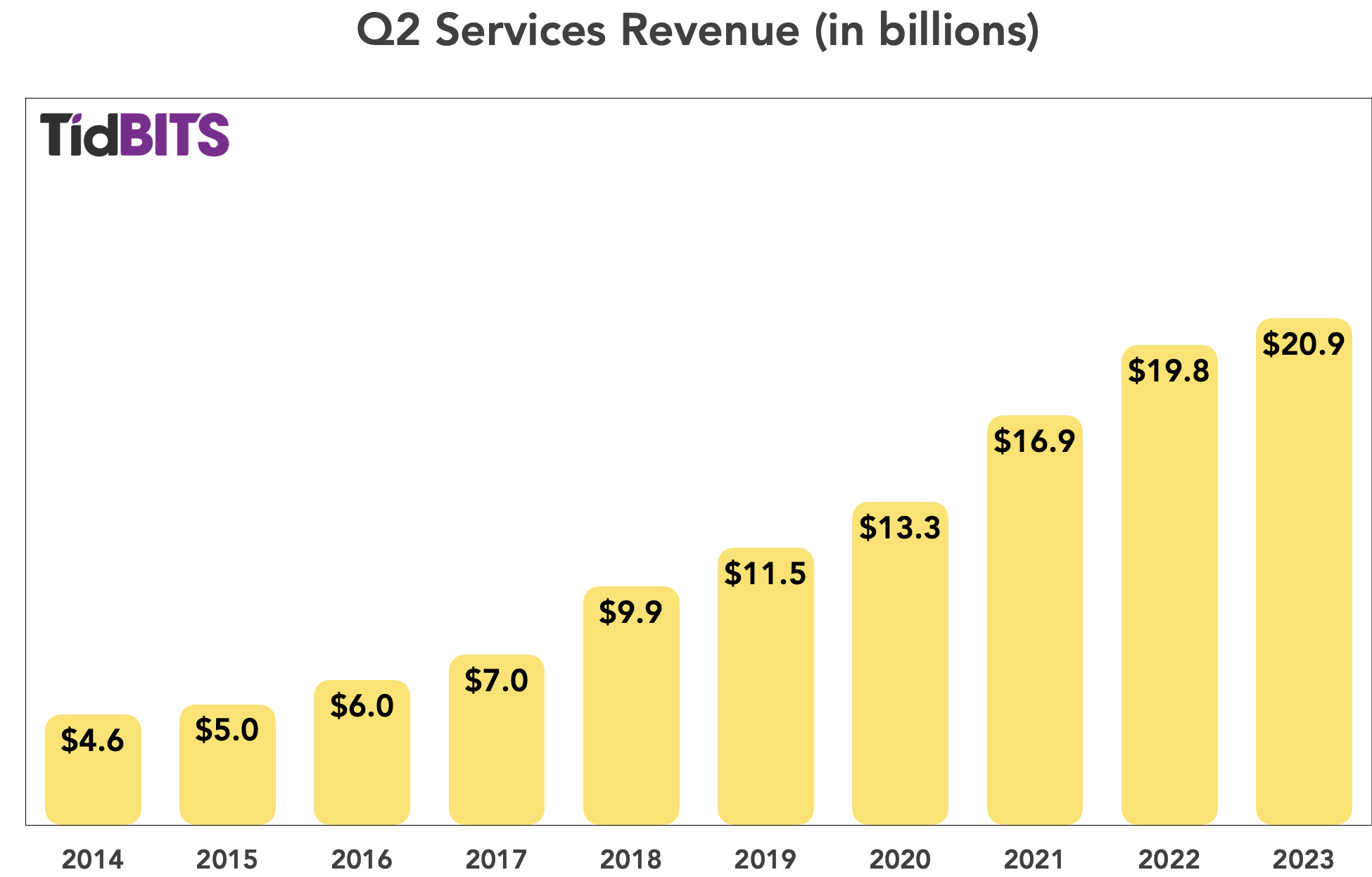

As with the iPhone, Apple’s Services business posted a modest revenue increase over last year’s figures, with $20.9 billion taken in, nearly 6% more than the $19.8 billion from the same quarter last year. Cook praised the vibrancy of Apple TV+ streaming offerings and made a point of mentioning the Academy Award for Best Animated Short Film that it won for “The Boy, the Mole, the Fox and the Horse.” Maestri emphasized Apple’s 975 million paid subscribers, a number that has doubled over the past 3 years, attributing much of this to the continually growing installed base of Apple devices.

However, in response to an analyst question, Maestri said mobile gaming revenues were off during the quarter partly due to the macroeconomic environment and partly due to “very elevated usage during the COVID years.” People have less time to play games when they’re not stuck at home. As for Apple’s latest financial service offerings, such as Apple Pay Later and the Apple Savings Account, Cook drew an analogy with the health features of Apple Watch, stating that Apple’s financial services aimed to help customers achieve better “financial health.” Hmm…

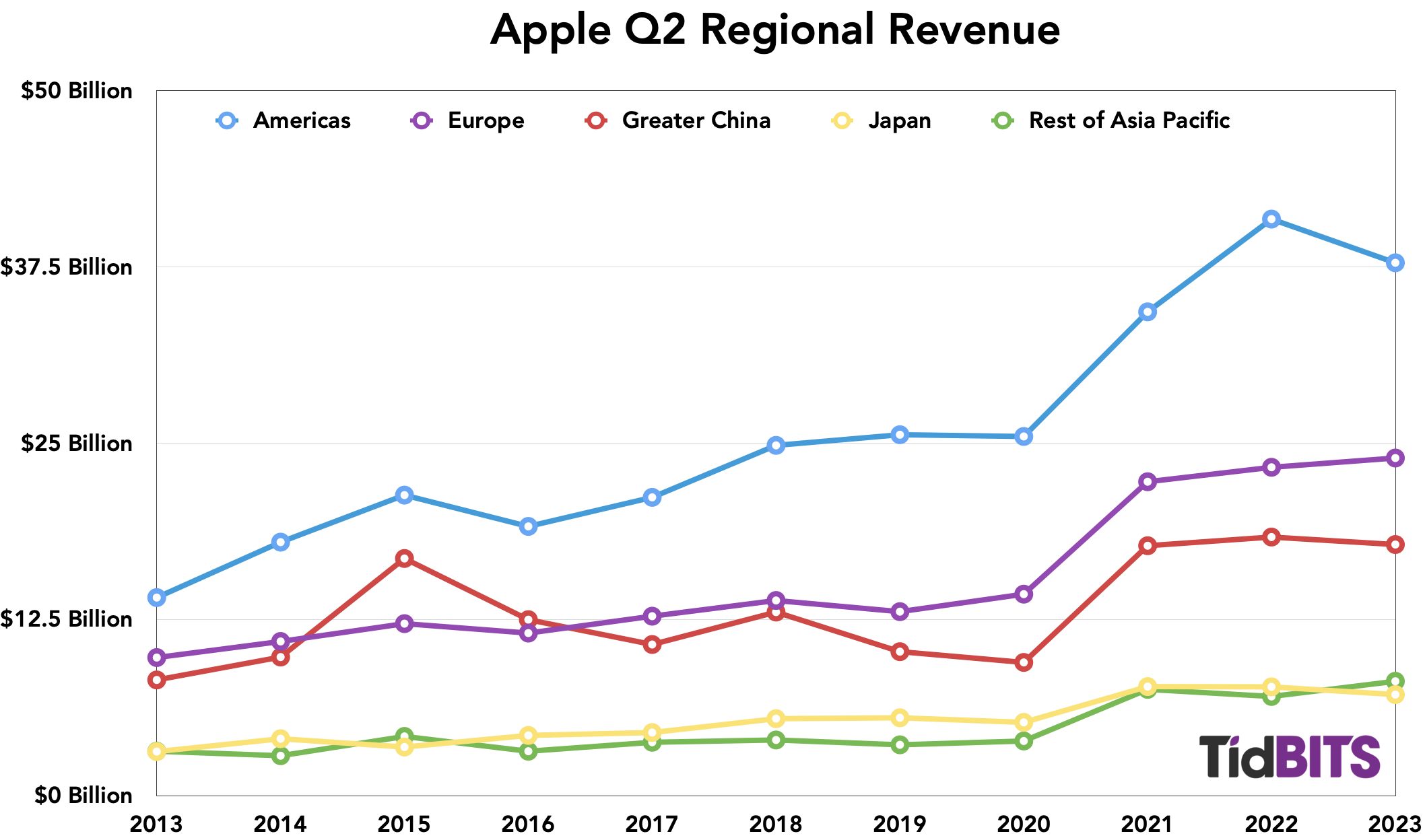

Regions

Apple’s revenues for its various geographical regions showed lower figures for the Americas, Greater China, and Japan. On the other hand, sales grew in Europe and Asia Pacific. The Asia Pacific sales were helped by double-digit growth in the emerging Indian market for Apple goods; Cook called out the growth in India’s middle-class as a hopeful harbinger of improved iPhone sales in the subcontinent. As for the Greater China results, he noted that even with a 3% decline in revenues, income from the region actually increased on a “constant currency basis” and that 60% of Mac and iPad customers in the region were new to the platform, a possible indicator of future sales.

The Future

Although Cook and Maestri said that the results for Q3 2023 would be comparable to this quarter, Maestri noted that the impact of financial exchange issues on those results would be flat and component prices are currently declining, a statement that concluded Apple’s conference call with analysts on a somewhat optimistic note.

Although constant growth seems to be the goal in our current economic model, it’s hard to see that Apple has done anything particularly wrong over the last quarter in not achieving that. New Mac and iPad releases would likely have improved those numbers, but product development and manufacturing at Apple’s scale isn’t something that can always be tightly scheduled. Apple’s next set of improvements will come, as they always do, and we’ll see if they drive sales the way the transition to Apple silicon in the Mac lineup has.

AirTag in the News: NYPD Recommends, Apple and Google Propose Industry Tracking Standard

The New York Police Department produced a video to accompany a recent announcement: stick an AirTag in your car to help with recovery in the event of theft. In conjunction with the NYPD’s announcement, New York City Mayor Eric Adams said a nonprofit had donated 500 AirTags to give away to NYC residents. Adams even held up a boxed AirTag, effectively giving Apple an endorsement and free advertising.

On the flip side of that news was a press release from Apple and Google about an industry standard the two companies jointly drafted to provide consistent presence-alerting behavior for tracking devices made by any company. This would include freestanding trackers like the AirTag, Samsung’s SmartTag, and a reported upcoming Google competitor, not to mention devices with less-comprehensive tracking coverage from Cube, Chipolo, and Tile. The standard would require compatible alerts, movement sensors, and identification across ecosystems, making it far easier for someone to detect unwanted tracking.

These two stories represent the tension inherent in ubiquitous, hard-to-detect tracking devices. On the one hand, they’re a powerful tool to enable the recovery of stolen items (or find lost objects, which is Apple’s primary goal for the AirTag). On the other hand, they’re the easiest method in human history to track someone’s whereabouts surreptitiously down to the minute. Any device that simplifies finding your own stuff will always have the effect of reducing other people’s privacy and increasing their risk; limiting tracking capabilities to reduce stalking also lessens the utility for item recovery.

Let’s look at these announcements.

Hill Street Bluetooths

While many statements made by politicians, retail stores, and police departments about rises in crime are overstated or simply inaccurate, it’s true that car theft is way, way up in most American cities—in some cases, two to four times higher in 2022 compared with the immediately preceding years!

It’s not that criminal masterminds suddenly decided stealing cars was in. Rather, models of Hyundai Motor Group’s Kia and Hyundai—about a decade of the former’s models and six years of the latter’s—have an extraordinarily easy-to-exploit flaw that went viral in mid-2022. Yes, it spread widely on social media. It can reportedly take a minute or less to drive off in one of the vulnerable models. Over eight million cars are affected. Hyundai took until February 2023 to release a software fix—one that must be installed at a dealer—that makes those models vastly harder to hijack.

This context is important for why the NYPD is suddenly pushing the AirTag. Near the end of 2022, the NYPD said nearly 13,000 cars had been stolen in New York City so far that year—32% more than in 2021. There are about 2 million registered cars in the five boroughs, so as many as 1 in 150 are being ripped off.

If this increase in theft could be attributed to organized crime, AirTags likely wouldn’t help. Professional thieves know to look for trackers and crush or toss them. They also find and remove sophisticated ones with GPS and cellular connections that can plug into a car’s diagnostic port or have their own battery. With an iPhone, Apple’s Android tracking app, or more sophisticated Bluetooth scanning apps, a thief who cares that they’re being tracked can find and disable the tracker. (This doesn’t include cars with embedded tracking and cellular systems; I expect those are more generally avoided and better at immobilizing the car when stolen.)

All reports indicate that a significant portion of the jump in thefts is due to opportunity. Somebody watches a YouTube or TikTok video and sees how easy it is to steal one of the vulnerable models. They lack the impulse control and self-preservation that keeps most people from committing crimes, and off they go.

A case in point: our older car was stolen several years ago. We thought it was gone for good until it was found several weeks later, unlocked and full of trash, in a supermarket parking lot. The thieves stole it and abandoned it as casually as though they were taking a bus. Had we had a tracker, we likely could have found it right away! (Our insurer paid generously to get it towed and repaired.)

Even so, Apple designed the AirTag to help find your lost items, not assist in theft recovery, so significant limitations remain in the NYPD’s message:

- Can’t share the live location: You must either ride with the police (unlikely), give them your unlocked iPhone (a bad idea), or relay the location to them. The NYPD video seems to show live updates. It’s much more likely that if you can tell the police where the car is parked, they’ll pursue tracking it down.

- Multiple owners: If multiple people use the same car at different times, such as in a family or business, a single AirTag allows only the associated owner’s Find My apps to provide location information. Apple doesn’t offer any sharing method within a family, either.

- Lack of interest by police: Despite the NYPD promoting the AirTag as a way to help recover stolen cars, many police departments have dramatically dropped the priority of these cases. See this, this, this, this, and similar articles.

Regardless, if you live in a city suffering from increased auto theft, putting an AirTag or third-party Find My tracker in your vehicles is likely worth the minimal investment. If you drive the same car as other people, one of you will have to be “it.” Everyone else will receive notifications whenever they drive the car or are a passenger without the paired owner in it. Apple gives you the option to mute alerts indefinitely in those cases. Find a hidden place to put the tag other than the glovebox.

Let’s not disregard bikes, too, which can easily cost thousands of dollars. Bike thefts increased dramatically for a time when bikes were scarce and prices sky-high. Those have tapered off but remain a constant burr in bikers’ saddles. You can stick an AirTag in a bag, but there are better options:

- TagVault: Bike: Elevation Lab makes several kinds of AirTag cases. The TagVault: Bike ($19.95) is waterproof and screws into a standard water-bottle cage mount. I reviewed it for Macworld.

- Knog Scout: A unique third-party Find My item, the Knog Scout ($59.95) offers two distinct kinds of protection. You can set a motion alarm over Bluetooth using its app and then enable or disable it while within range. For broader tracking, the Scout also supports the Find My network. It’s also rechargeable via USB-C without unmounting. See my full review.

- VanMoof bikes: Only one e-bike maker has integrated Find My tracking into its bikes so far. VanMoof includes tracking in some of its models.

A Standard to Protect against Unwanted Tracking

In an acknowledgment that tracking technology can be used for stalking, Apple and Google released a draft of a proposed industry specification via the well-accepted Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) process. With the blunt title “Detecting Unwanted Location Trackers,” the spec stakes out the problem territory in a technical way and suggests how to provide significant minimum rules that all devices complying with the standard would have to support.

The spec largely matches Apple’s implementation of anti-tracking elements in the Find My network, though the document contains more explicit detail about how this information must be encoded. In particular, the standard describes all the conditions in which a tracker is separated from the tracker’s owner, as defined as a device in the iCloud set for a single Apple ID connected to the iPhone or iPad with which an AirTag or Find My item was initially paired.

Apple’s initial AirTag capabilities didn’t account for all the ways in which unwanted tracking could occur and allowed various opportunities in which a determined party could keep tabs on someone without their knowledge. After some furor (see “Apple Explains How It Will Address AirTag Privacy Issues,” 12 February 2022), Apple made a few tweaks that were considered improvements by groups that help victims of domestic violence and other kinds of stalking, such as the National Network to End Domestic Violence. However, Apple’s changes weren’t sufficient for these and other organizations advocating for personal privacy.

The protections Apple currently offers are:

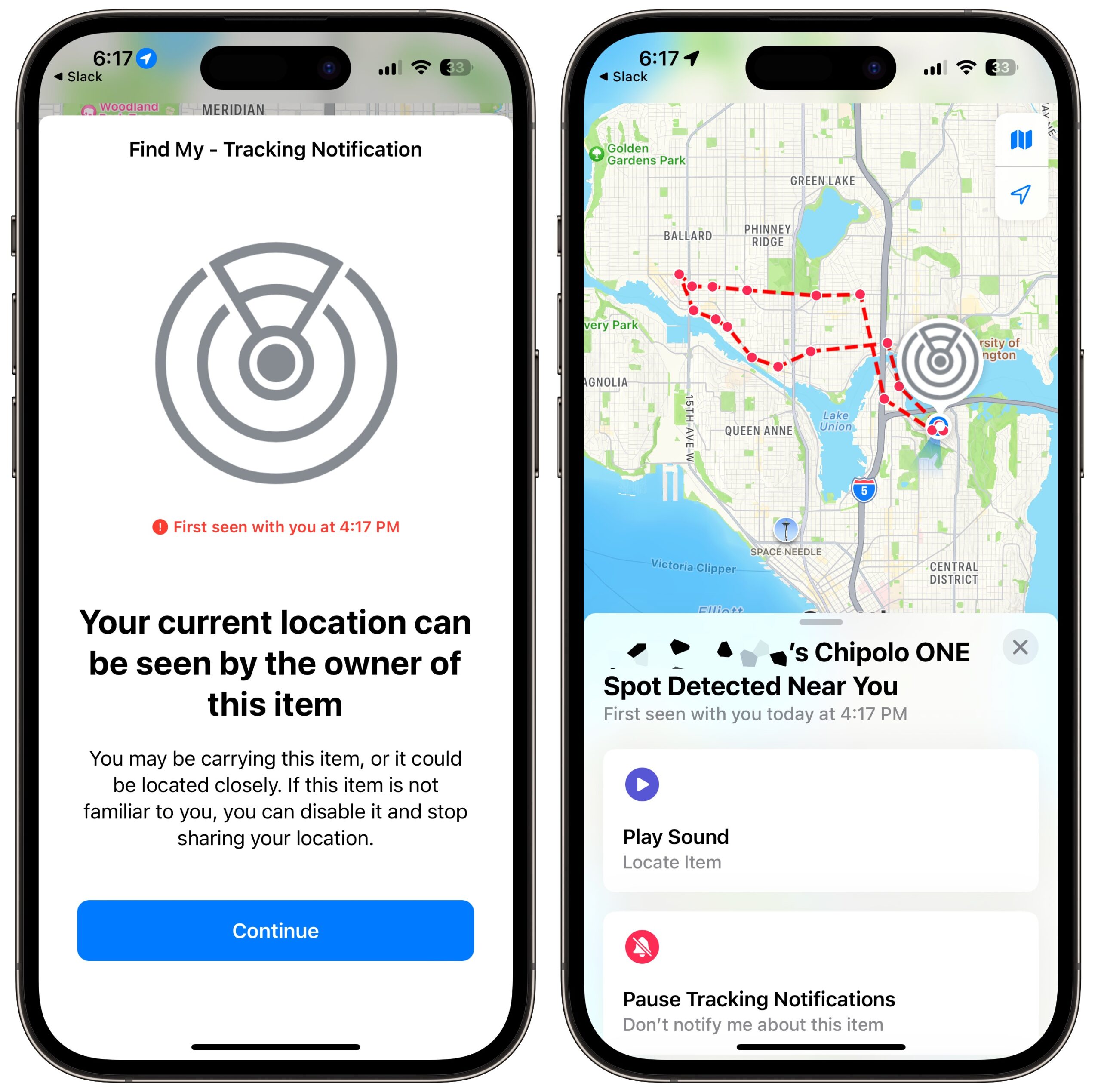

- If you have an iPhone or iPad that’s consistently relaying information about a nearby Find My item that moves with it, your device will display an alert and provide information about how you can cause it to play a sound; you can use Precision Finding to locate it if it’s an AirTag and you have an iPhone with an ultra-wideband radio. Once found, you can bring it near an iPhone or Android phone with NFC to reveal limited details about the owner and get instructions on how to turn it off or remove its battery.

- If a Find My item is separated from its owner and moved, it makes a loud noise. To avoid letting a stalker predict when the sound might be made, Apple picks a random interval between 8 and 24 hours before it first makes a noise. (If the tracker remains fixed in place, it remains silent because the owner would have had to be near when it was put there—though that means the owner might then know the item hadn’t moved.)

- Apple doesn’t provide movement alerts. You can check an AirTag at any time through a native Find My app (not via the iCloud.com site), but you are never alerted to movement. This frustrates some people who want Find My to work like a movement detector that would alert you if your car or bike were in the process of being stolen.

(You can read more about these protections in “When You’re Told an AirTag Is Moving with You” (4 June 2021); about AirTag use cases in “13 AirTag Tracking Scenarios” (13 May 2021); and some early, seemingly overstated panic about AirTags in “AirTags: Hidden Stalking Menace or Latest Overblown Urban Myth?” (11 January 2022). I’ve also written an entire book on AirTags and the Find My app and ecosystem, Take Control of Find My and AirTags.)

The most significant gap in those protections afflicts non-Apple users, who would only find out if a tracker moved with them when it played a sound. And it’s possible to remove the sound-generating part of an AirTag using instructions easily found online.

An Android owner could install Apple’s Tracker Detect app, but they must manually use it to identify a Find My item traveling with them. Likewise, those using trackers from other companies, currently more limited in reach, must have a compatible app or hardware. (When AirTags were launched, Tile offered no method by which people could become aware of nearby Tile trackers; the company added the feature in March 2022.)

The Apple/Google proposal aims to counter this lack of discoverability. Its goal is to make all platforms and tracking devices compatible with each other for the purposes of discovery. As long as you or anyone around is carrying an Apple or Android-based mobile device, all trackers should produce alerts about their presence and let you take action.

The draft standard defines minimum requirements for devices that, one hopes, will become branded and certified in some way. Failing that, reviewers will ostensibly call out devices that fail to conform. I know I will!

In general, the proposal is pushing capabilities that will let any hardware device that can detect any kind of tracker via Bluetooth detect all of them. It requires trackers to produce sound at least to a standard-defined loudness, a discoverer to be able to trigger that sound and have it play for at least 5 seconds, and all trackers to have a method to be disabled, even if it’s more involved than removing a battery. For instance, a Chipolo CARD Spot, which has an integral battery, already offers such an alternate method for disabling the tracker: instructions tell you to hold a button on the card for 30 seconds until you hear it start beeping and then release the button after the tenth beep.

The standard also specifies that all items must incorporate serial numbers. During pairing, makers must offer a registry process that associates the serial number with the owner’s phone number and email address. However, the spec has no requirement for validating the number and address, a task seemingly left up to the device makers. The registry information remains in the hands of the maker unless requested by law enforcement. (Note the spec says “request,” not “warrant” or another requirement with a higher burden of proof, providing a privacy and safety tradeoff for those who use these devices for legitimate purposes.) In any app that can detect standard trackers, a person finding it will be able to view the serial number and small portions of the phone number and email address, such as (***) ***-5555 and b********@i*****.com.

The spec explains why the phone number and email address should be displayed like this in straightforward terms:

In many circumstances when unwanted tracking occurs, the individual being tracked knows the owner of the location-tracker. By allowing the retrieval of an obfuscated email or phone number when in possession of the accessory…this provides the potential victim with some level of information on the owner, while balancing the privacy of accessory owners in the arbitrary situations where they have separated from those accessories.

In other words, in circumstances that involve intimate partners, acquaintance stalking, and similar scenarios, the victim will likely be able to identify the perpetrator with a few digits or letters, making it easier to obtain legal, law enforcement, and court help.

I should note that Apple’s other trackable devices—everything from the AirPods to a MacBook Pro—currently have fewer protections than Find My items: they don’t bleep or bloop or send alerts in the above cases. This is likely because they’re generally larger, much more expensive, and have short battery lives. Apple’s AirPods and Beats earbuds are probably the smallest items that can be tracked via the Find My network, and they might be able to send tracking signals for only a few weeks. Go up in size to an iPhone, iPad, or Mac, and you’re looking at battery life ranging from a few days to a week or two. In comparison, an AirTag and similar compact device can track for 6 to 12 months before its lithium-ion cell battery dies. The persistence and ease of hiding make the difference.

The draft proposal incorporates some of these bigger devices by dividing tracking into two categories: “small and not easily discoverable” (an AirTag or AirPods) and larger and “easily discoverable” (a bicycle or MacBook Pro). To fit into that latter category, a tracker’s enclosing hardware must fit any of the following criteria:

- One dimension: Larger than about a foot (30 cm) in any dimension, like a cane with an embedded tracker

- Two dimensions: Larger than about 7 by 5 inches (18 by 13 cm), covering some iPads, but not any smartphones

- Three dimensions: Larger than about 15 cubic inches (250 cm3) or with equal square faces a 2.5-inch cube—including the iPad Pro 11-inch and 12.9-inch models and any laptop

For devices that aren’t easily discoverable, the document says best practices are required; for larger items, they’re recommended but not required.

The draft omits any discussion of appropriate ways to share access to trackers among individuals. That could be mediated from the standpoint of avoiding stalking: consensual sharing doesn’t decrease privacy and would allow something like a shared car or bike to be beneficially tracked by all who use it.

Parties that were previously highly critical of the AirTag protections responded extremely positively to the Apple/Google announcement. The National Network to End Domestic Violence and the Center for Democracy & Technology released a joint statement in which the CDT’s head, Alexandra Reeve Givens, said, “A key element to reducing misuse is a universal, platform-level solution that is able to detect trackers made by different companies on the variety of smartphones that people use every day.”

Apple and Google’s press release stated, “Samsung, Tile, Chipolo, eufy Security, and Pebblebee have expressed support for the draft specification.” However, only Pebblebee acknowledged the announcement, linking to it from its press page. Tile hasn’t updated its press page since January 2022.

Because Apple and Google are backing this spec, it will likely reach fruition quickly. From what I can tell after reading the draft, some existing devices—almost certainly all AirTags—could be updated to be compliant through firmware updates. Other product lines will require new hardware.

Apple and Google could also add app store requirements for apps that work with physical tracking devices, requiring that the devices comply with these new guidelines. Apple already requires all third-party Find My items to conform with Apple’s rules.

A broader adoption of interoperable, discoverable tracking standards could let society enjoy the benefits of tracking devices while reducing the likelihood of abuse—or at least making it far more likely that any antisocial uses are discovered quickly.