#1667: OS Rapid Security Responses, 1Password and 2FA, using Siri to request music

Apple has released Rapid Security Response updates for iOS, iPadOS, and macOS to address a severe WebKit vulnerability that’s actively being exploited—update soon. Continuing in the security vein, Adam Engst explores the question of whether having 1Password auto-fill both passwords and security codes is true two-factor authentication. (It’s not. But it’s still worthwhile.) Adam then changes gears to explain how he’s not entirely happy with how he uses Siri to request music on HomePods and to solicit ideas from those who like their approach. Notable Mac app releases this week include Zoom 5.15.2 and DEVONthink 3.9.2.

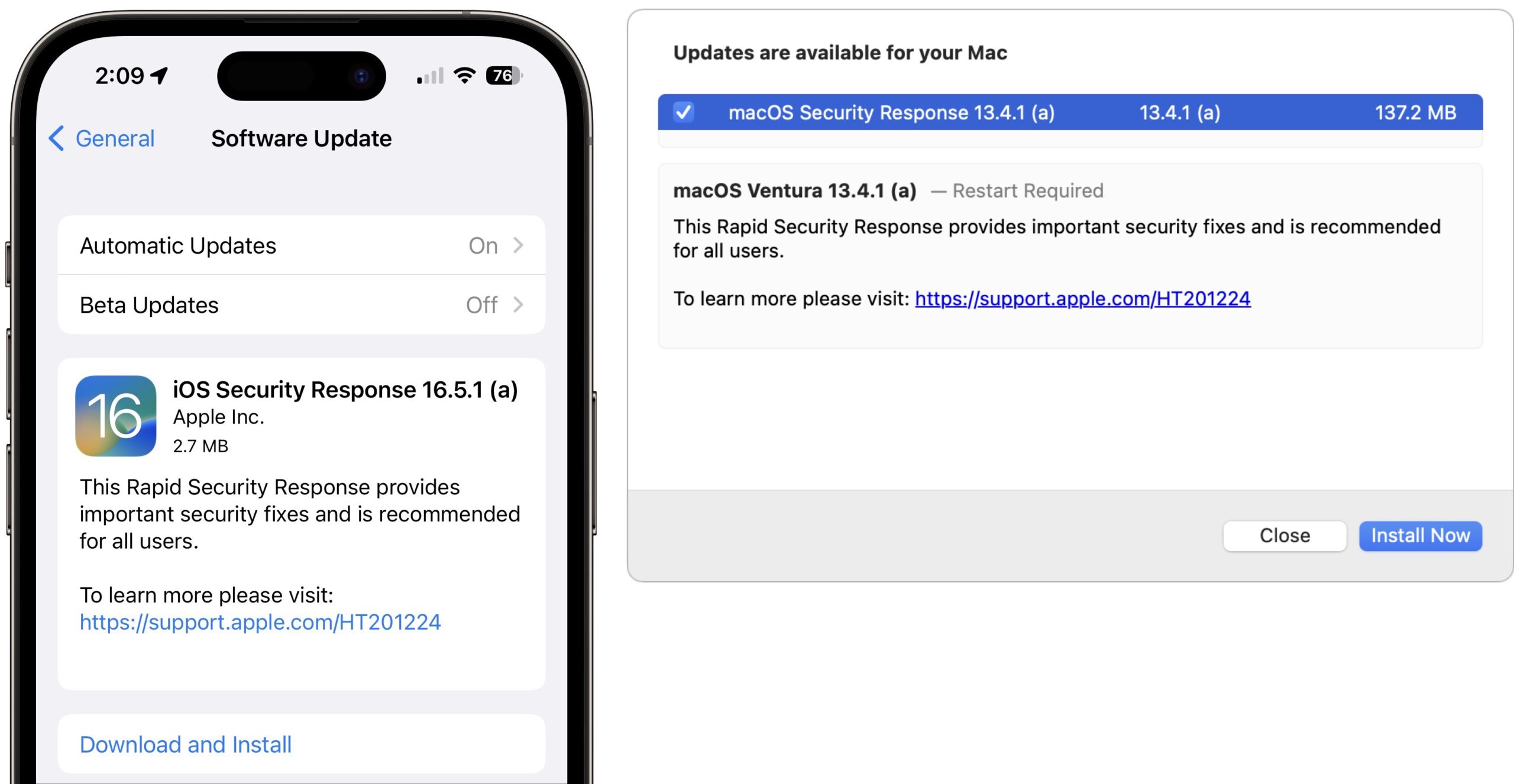

Rapid Security Responses for iOS/iPadOS 16.5.1 (a) and macOS Ventura 13.4.1 (a)

After publication, Apple pulled these updates due to the website loading issues hinted at below. You can remove the Rapid Security Response updates as outlined in “What Are Rapid Security Responses and Why Are They Important?” (2 May 2023) or use a different Web browser for the affected sites. New Rapid Security Responses should be available soon. –Adam

Apple has released Rapid Security Response updates for iOS 16.5.1 (a), iPadOS 16.5.1 (a), and macOS Ventura 13.4.1 (a) to fix a WebKit vulnerability that could allow malicious Web content to execute arbitrary code. Unsurprisingly, this vulnerability is being actively exploited, and I encourage you to install these updates as soon as feasible.

It won’t take long, although the updates require a restart. The entire process took less than 4 minutes on each of my devices: an iPhone 14 Pro, M1 MacBook Air, and 2020 27-inch iMac. Interestingly, the iPhone update was only 2.7 MB, and the iMac update was 6.4 MB, but the M1 MacBook Air update was far larger at 137.2 MB.

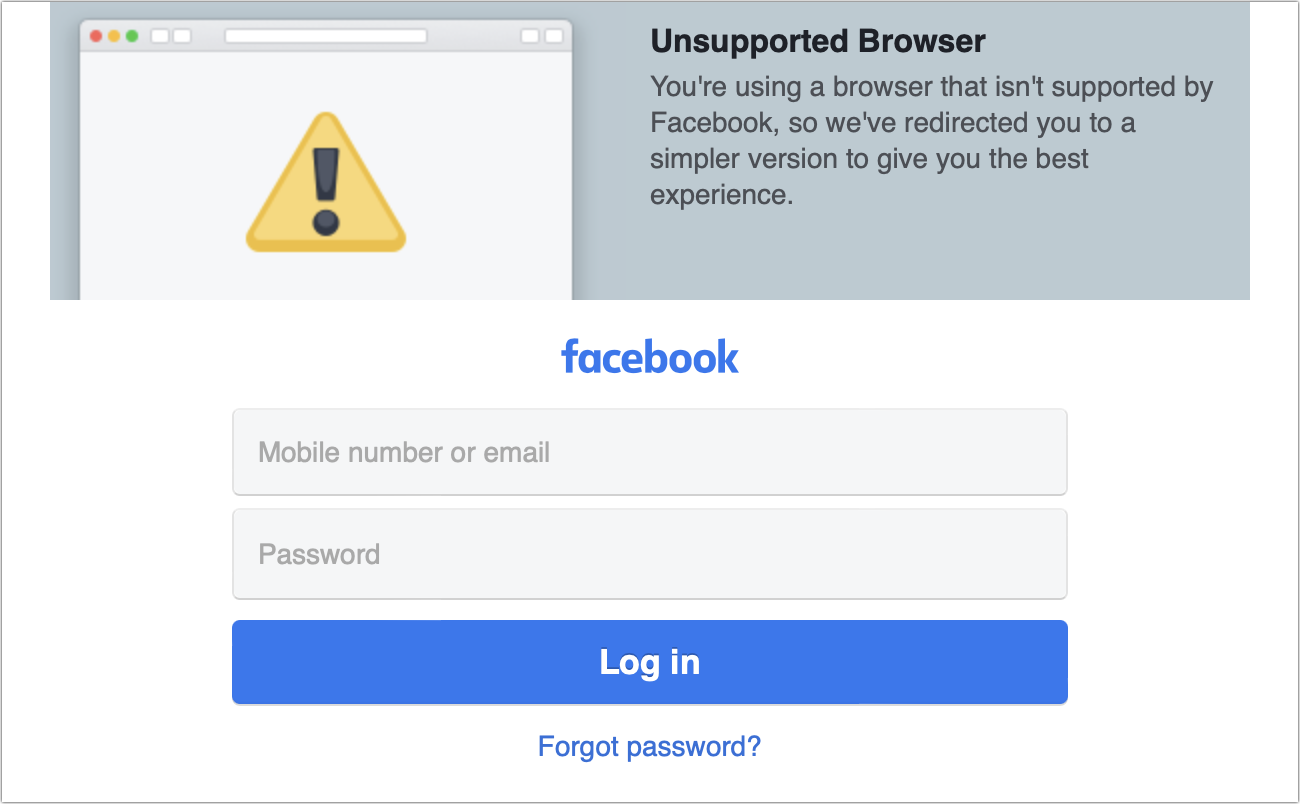

Thanks to Will Mayall for pointing out that Facebook’s Web browser detection code doesn’t recognize the new Safari 16.5.2 (a), forcing you to use the mobile version of the site. Facebook will likely update soon, and Apple will probably release a Safari update for older versions of macOS shortly.

Let us know in the comments if you experience any other issues during or after the updates.

Two-Factor Authentication, Two-Step Verification, and 1Password

In “LastPass Publishes More Details about Its Data Breaches” (3 March 2023), I talked about how I decided to move my two-factor authentication (2FA) codes from Authy to 1Password and how the process was fussy and time-consuming. However, it was worth the bother of migrating: having 1Password auto-fill time-based one-time password (TOTP) codes is much easier than opening Authy, finding the entry, copying the generated code, and pasting it into the browser.

I dislike putting all my security eggs in one basket, and having 1Password contain both kinds of secrets—account passwords and TOTP codes—has given me some pause. I’m pretty confident in my 1Password setup and in 1Password’s integrity and security, but the fact remains that if someone were to gain control of my 1Password account, two-factor authentication wouldn’t restrict access to my most important accounts. Does having 1Password generate TOTP codes even qualify as two-factor authentication? Thanks to a recent blog post by 1Password’s Megan Barker, I now know it does not meet the definition.

In a slight departure from Barker’s post (her “verification” is another example of authentication), there are two aspects to creating and logging into an account:

- Identity: The first question is, “Who are you?” and the answer is an identifier. It’s generally an email address, often coupled with a username. In the real world, an identifier might be a driver’s license or passport. You can have multiple identities, even within the same system.

- Authentication: How do you prove that you are who you say you are? That’s the job of authentication, the process of confirming your identity by entering a secret shared with the service. Exactly what that entails can vary. When setting up an account, authentication often involves clicking a link in an email sent to the address you provided. After initial setup, the shared secret is most commonly a password, but it could also be a magic link, which apps like Slack offer. Risk-based authentication might ask for more information, such as how Apple devices sometimes ask for passcodes or passwords from other devices in your trusted set. For high-value accounts, authentication might involve showing a government-issued ID, and on occasion, I’ve even had to do online video identity checks.

Passwords can be guessed or stolen, so many sites allow multifactor authentication for additional security. There are three common types of online authentication factors:

- Something you know, like a password or a PIN

- Something you have, like an iPhone, Apple Watch, or hardware security key

- Something you are, generally biometric recognition of your face or fingerprint

For multifactor authentication, you need at least two of these. (While providing three authentication factors may seem like overkill, it offers higher security and is required in some specialized fields and parts of government.) Here’s the catch: Each factor must be separate and distinct to be valid. Implemented correctly—which Apple has—biometrics are always separate and distinct.

Without requiring biometrics, it’s not so simple. Using 1Password to auto-fill your username and password provides one authentication factor, but if you also have 1Password on the same device auto-fill the TOTP code, it’s not separate and distinct, and thus the TOTP code doesn’t represent a true second factor. Instead, it’s something called two-step verification (2SV). If you remember this term, it’s because Apple responded to the 2014 scandal that revealed personal iCloud photos by deploying an early two-step verification system even though iCloud wasn’t hacked (the breaches were likely identity-based password guessing).

Two-step verification is a significant improvement over plain password-based authentication because it presents an additional hurdle to anyone attempting to log in to your accounts. But as long as that TOTP code is delivered on the same device and in the same pathway—you unlock 1Password for passwords and TOTPs using the same method—it’s not two-factor authentication. That’s the case if the TOTP code comes from 1Password, Authy, or some other authentication app running on the same device you unlock using a password, Touch ID, or Face ID. However, logging in on your Mac and looking up the TOTP code in Authy on your iPhone would be true two-factor authentication.

Given how many platforms it runs on, it would seem that 1Password could implement true two-factor authentication. I’m sure there are subtleties involved, but at a base level, all requests for a TOTP code could generate a push notification on another of the user’s devices that would have to be acknowledged before the login would proceed. Attempt to log in on a Mac, and you’d get a push notification requesting confirmation on your iPhone and Apple Watch. Log in from an iPhone, and you’d get the notification on your Mac and Apple Watch.

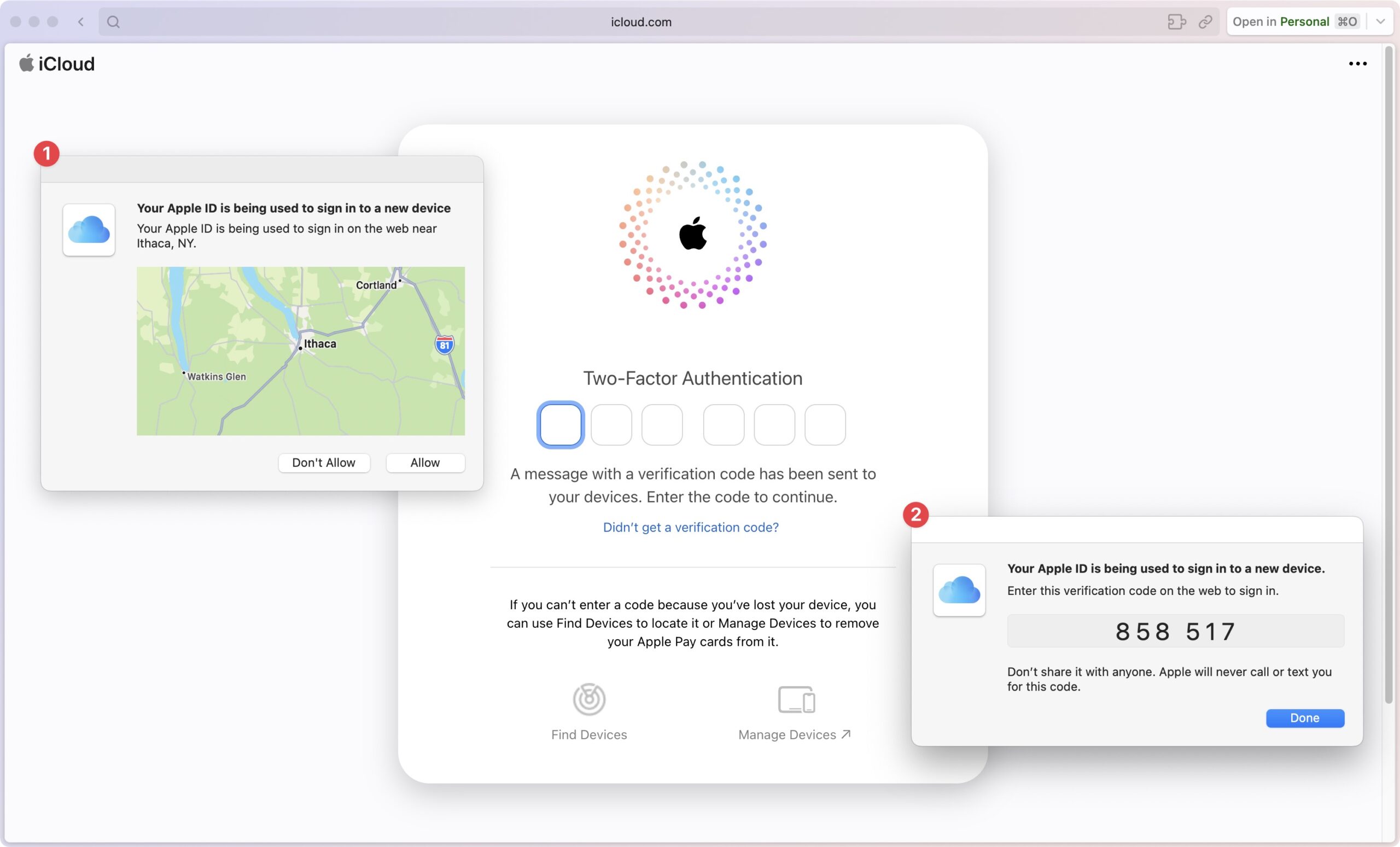

I’m uncertain if Apple’s approach to two-factor authentication for logins to Apple websites counts or if it’s really a form of two-step verification. For instance, when you log in to iCloud.com, Apple first presents a dialog asking if you want to allow the login to proceed. If you agree to that, it gives you the TOTP code. As you can see in the screenshot below, that’s all happening on the same device, so it wouldn’t seem to be true two-factor authentication. (More problematic is how Apple lets you fall back on an SMS text message to a trusted phone number; SMS can be compromised without physical access.)

Apple’s answer is that I’ve designated my Mac as a trusted device and logged in. Because I have the device and can unlock it, it’s safe to provide the TOTP code. (Of course, the two-factor authentication prompts triggered by adding a trusted device to your set—as opposed to logging in to an Apple website—appear only on other devices.)

I’m not sure I buy Apple’s answer—if someone were to steal my Mac and guess my login password, they could accept two-factor authentication prompts just as in the iPhone passcode theft scenario we wrote about earlier this year (see “How a Thief with Your iPhone Passcode Can Ruin Your Digital Life,” 26 February 2023, and “How a Passcode Thief Can Lock You Out of Your iCloud Account, Possibly Permanently,” 20 April 2023). Maybe it’s more like 1.5-factor authentication: not as weak as a password but not as strong as a TOTP code generated on a separate device.

Regardless of the technicalities, two-step verification increases security significantly. 1Password users should enable it whenever possible, allowing it to auto-fill for ease of use. If you need an even higher level of security, Apple now supports hardware security keys for true two-factor authentication; see “Apple Releases iOS 16.3, iPadOS 16.3, and macOS 13.2 Ventura with Hardware Security Key Support” (23 January 2023). For the vast majority of users, though, such hardware keys are overkill.

How Do You Request Music Using Siri?

Usually, I like to offer solutions in TidBITS articles, but when it comes to the black box of controlling Apple Music using Siri, I have no sense that my approach is ideal. So I’m going to describe my frustrations, and I hope those of you who have different approaches that work well for you will chime in with suggestions.

Tonya and I have two HomePods and a HomePod mini, and overall, we like them a lot for listening to music and controlling our HomeKit-driven lights. Nevertheless, Siri has problems, and it’s common to have to repeat a missed command or rephrase a request to get Siri to behave as desired.

Now we know why. In How Siri, Alexa and Google Assistant Lost the A.I. Race, New York Times reporters explained that Siri is essentially a “command-and-control system” that has to be hard-coded to understand all the words in a request. Siri’s database contains a massive list of words, including the names of musical artists, albums, and songs. And, of course, it understands various music-related commands. Many of these you’ll have guessed, but others will likely be new to you. The best roundup I’ve found is at Smartenlight, though it’s still not entirely satisfying. The article is from December 2019, and quite a few of the commands didn’t work or worked sporadically for me. Your mileage may vary.

My frustrations with using Siri to play music on HomePods are twofold:

- I sometimes struggle to think of what I want to listen to without a visual cue.

- Once I have a sense of what sort of music I want to hear, I have trouble getting Siri to play it.

My problems may be partly age-related. Without playing into stereotypes about memory loss, the number of artists I have in my Apple Music library is vastly larger than those whose CDs we owned before music moved online. There’s a lot more to keep in my head now than 25 years ago.

The way I listen to music has also changed significantly, twice. Neither Tonya nor I had many record albums as teens—they were too expensive for us—and CDs caught on once we were in college, so most of our music was originally in that format. Starting in the early 1990s, we played music in a six-CD changer, and once we moved to a larger house with separate offices, we added a pair of portable boombox stereos that also held six CDs each. We’d look through our alphabetized collection, select six CDs, and play them for a few days, often on shuffle, with the CD jewel boxes extracted from the shelf and prominently displayed.

Jeff Robbin put an end to that era. With Bill Kincaid and Dave Heller, he wrote SoundJam, which Apple later bought and turned into iTunes. (I last spoke with Jeff in person when he was walking the floor with Steve Jobs at the Macworld Expo after Apple’s acquisition—it was also the last time I met Jobs.) Starting in 1999 with SoundJam and then iTunes, I ripped all our CDs to MP3 format and played them from a laptop, first through directly connected speakers and later using AirPlay from an AirPort Express attached to a stereo. When Apple introduced the iTunes Store, we purchased new music there because it was clear that physical CDs were on the way out. Regardless of how the music got into the Mac, finding something to play involved scrolling through a list of artists and selecting an album.

So I have spent decades selecting music by looking through an alphabetized collection—either a lineup of CDs on a shelf or a scrolling list of artists. The CDs were particularly effective because favorite artists stood out by virtue of occupying more shelf space, whereas in iTunes and now Music, David Bowie takes up the same amount of space as Vib Gyor. (Until searching, I had no idea who Vib Gyor is, and they’re not in Apple Music. I think the iTunes Store gave their “We Are Not An Island” song away in its New Music Tuesdays promotions, which were a slightly helpful way to find new music.)

With voice commands directed to a HomePod, though, I have to figure out what I want to listen to without any visual reminders that might trigger a positive—or negative—response, and I’m not happy with how well I’m doing that. I find that I listen to a relatively small subset of music simply due to the limited details I can bring to mind at any given time. Of course, I could pull out my iPhone and scroll through the Music app whenever I want to play music—and I do that occasionally, but it’s too much work most of the time.

How My Brain Manages Music

With that in mind, here’s how I think about music. (Before someone comments, I rarely listen to classical, which I know is extremely different.) I remember my favorite artists fairly well and categorize them into mental buckets. The Beatles go with the Rolling Stones and the Yardbirds. Leonard Cohen matches up with Bob Dylan and Jennifer Warnes. The Eagles fit into the same category as Jackson Browne, Fleetwood Mac, and Carole King. Tom Petty and the Wallflowers. I can’t even quite remember the difference between the Counting Crows and the Crash Test Dummies until I hear a song. Given the range of his music, David Bowie stands alone.

Where I have more trouble is with artists I’ve discovered in recent years. Off the top of my head, I can come up with Dave’s True Story, Farewell Milwaukee, Thea Gilmore, Chris Isaak, BLACK, Joan As Policewoman, Mel Parsons, J.J. Cale, and others. But there are plenty of artists I’ve found and enjoy whose names I can’t pull out of my increasingly full memory (looking through my artist list, they would include Asaf Avidan, Amy Winehouse, Of Monsters and Men, and Warhaus). I always add newly found artists to my Apple Music library, so I might see them when scrolling through a list, but I have trouble remembering them when trying to start music on a HomePod.

I seldom start music by playing an album because I don’t know most album names. Those I can think of go with our historical CD collection, which now lives in what the family that built our house considered their media room but we use primarily for storage. It’s an ode to the media formats of 1984, with purpose-built shelves for CDs, a cabinet with dividers for LPs, a place for stereo equipment that would connect to in-wall speaker wiring throughout the downstairs, and bookshelves surrounding a spot for a 19-inch CRT television, complete with a custom shelf for a cable box. Our books, CDs, and record albums occupy their designated shelves, and we even have an old stereo system and speakers in the room, but it all sits unused. The HomePods are much easier to use, and the audio quality is perfectly fine for our needs.

I’m only slightly more likely to remember a song title than an album; some have stuck in my head, but most others are a mashup of the title and the most notable lyric. Regardless, if I want to listen to music, I want to hear more than a single song, so I rarely ask for just one.

Finally, I’ve never found playlists helpful. Even though I can say which artists I think are similar, I don’t have words for those collections, and my somewhat obsessive personality has trouble with any groupings I try to create—there are always songs that are exceptions or artists who should be added but slip my mind. With over 11,000 tracks in my Apple Music library, some of which are replicated multiple times due to songs appearing on multiple albums, I find the idea of trying to make sensible playlists overwhelming.

Playing Music with Voice Commands

Here’s what I do to cue up music with voice commands and where my approach falls down.

Despite my trouble remembering many artist names, my most common command is “Hey Siri, play music by <artist>” because that’s what I’m going to remember most easily. It also works well for getting something playing, apart from BLACK, where saying, “Hey Siri, play the artist BLACK” works most of the time on the HomePods but seldom on the iPhone or Mac.

However, asking for an artist suffers from two problems. First, it seems to prefer the artist’s top songs, which makes perfect sense when playing an unfamiliar artist but gets old with an artist you want to listen to regularly. When I notice Siri overemphasizing hit songs, I sometimes try again with “Hey Siri, shuffle music by <artist>.”

Second, my real goal is to listen to music that the artist represents. Most of the time, when I’m asking for the Eagles, what I really want is a combination of the Eagles, Jackson Brown, Fleetwood Mac, and so on. Previously, such a set list was readily accessible with “Hey Siri, play music like the Eagles” or “Hey Siri, create a radio station based on the Eagles.” When I try those commands now, however, Apple Music plays only songs by the named artist. I’ve verified this by skipping song after song—I never get music from other artists.

(As I write this, I’m doing some of the testing on my iMac, where I usually rely on the Music app rather than Siri. So, of course, just to prove me wrong, “Hey Siri, play music like the Eagles” did what it was supposed to on the Mac, just seconds after it failed to work correctly on a HomePod. So, along with the BLACK example above, add to the list of complaints about Siri that it doesn’t act the same on all of Apple’s platforms.)

A better approach has been to wait until a song that exemplifies the type of music I want comes on and then to say, “Hey Siri, play more like this.” That usually triggers an interesting collection of songs from different artists. I’ve tried to short-circuit this process by asking for music like a song, especially after Tonya had notably good luck with music like David Bowie’s “Tonight,” but that has proved maddening. No form of the “play music like” command recognized “Tonight,” even when I specified it was from Bowie, and I only managed to get the HomePod to play the song at all with this exact command, “Hey Siri, play David Bowie’s Tonight.”—all other variants failed. Now that I look the song up in the Music app, perhaps it’s problematic because it’s sung by both David Bowie and Tina Turner, but how is anyone supposed to guess that without liner notes?

Often, I give up on playing an artist and say, “Hey Siri, play my music,” which shuffles music from my extensive Apple Music library. That’s quite effective because my library is both curated and quite large—I’ll probably enjoy what I hear and probably won’t have heard it recently. But because it’s random, the music genre can vary greatly from track to track, which I don’t like. It might even play Christmas music, which I categorically never listen to other than between Thanksgiving and New Year’s.

I may forget the exact wording and instead say, “Hey Siri, play my favorites,” which accurately triggers a smart playlist that collects all the songs I’ve said I “loved.” I can’t remember if I created that playlist or if it shipped with iTunes or Music at some point, but it contains 450 songs. I do indeed really like all of them, but I’ve heard them so many times that they can get boring.

For some reason, saying, “Hey Siri, play my favorite music,” currently triggers a song called “favorite crime” by Olivia Rodrigo, who I’ve never heard of before. It’s nice enough, but it’s not even in my Apple Music library, much less some sort of favorite. I can’t imagine why Siri plays it.

On the other hand, saying, “Hey Siri, play music I like” to create my personal station works pretty well, selecting both songs from my library and others that are similar. Again, the genres can vary more than I’d prefer, but at least it guesses pretty well.

Apart from 1980s rock from my teenage years, I rarely ask Siri for music from a genre or time period because the results are too random. Apparently, I don’t think like the people at Apple who develop playlists.

That said, I have long wanted the ability to access a subset of my library this way, and the Smartenlight article claims that saying “from my library” should do that. It seems to work for artists, which could be handy if you want to avoid specific albums by an otherwise favorite artist. But while “Hey Siri, play <genre> from my library” works with some genres (blues, country, jazz, and rock) on my iPhone, it fails nearly every time on both the HomePod and the Mac.

You can also ask Siri to play music for certain activities and moods, but those commands trigger pre-made stations. Whenever I try one of these, I recoil in horror from what it plays. Sadly, you can’t ask Siri to limit music for an activity or mood to tracks from your library.

So that’s me. What do you do?

ML and AI to the Rescue?

I realized we’re deep into wishlist territory here, but to my mind, the solution has to come from ML and AI.

It’s surprising that Apple hasn’t applied its machine-learning chops to personalized recommendations in Apple Music—or at least promoted how it has done so. Every Apple Music user must generate a vast amount of data Apple could use to personalize music feeds. What sort of music do you listen to at different times of day or days of the week? Which artists or genres make up the majority of your library? Which do you play the most often, and which songs are played disproportionately too little for their similarity to more popular tracks? Which automatically generated suggestions do you skip because you hate them? Do you play different music in different locations? How about in the car?

Apple must be doing some sort of algorithmic selection of songs for its autoplay feature that plays similar songs after a requested song or album ends, and that works reasonably well. But given that Apple doesn’t promote how it’s using machine learning to play the best music for you at any given moment, I suspect that it’s nowhere near what the company has done with computational photography and other ML-driven photography features.

Siri is a tougher nut to crack, given its importance to the Apple ecosystem. Siri may not be as good as we’d like now, but Apple can’t afford for it to get worse. Generative AI like ChatGPT could be more flexible about its input, so we wouldn’t be forced into today’s often stilted speech to get good results. But much of what Siri does might not work well with the well-known accuracy problems of generative AI. We don’t want Siri making up hours for a recommended restaurant, messing up basic math, or confidently returning invented details for a Web search.

However, music recommendations are fuzzier and have lower stakes. If you were to say, “Hey Siri, play hard-driving workout music from the 1980s along the lines of Queen and the theme songs to the ‘Rocky’ movies,” there’s no right answer. There are wrong answers, but when I asked ChatGPT to recommend music using that prompt, the suggestions were spot on. (In contrast, Siri came up with some songs that could never be described as “hard-driving.”) ChatGPT also produced reasonable suggestions in response to other complex music prompts.

Apple Music might be the perfect place for Apple to experiment with generative AI input and output.