#1644: Explaining Mastodon and the Fediverse, HomePod Software 16.3 and tvOS 16.3, GoTo breach

With Twitter awash in controversy surrounding pretty much everything Elon Musk does, millions of people are decamping to Mastodon. But, as Glenn Fleishman explains in a pair of in-depth articles, Mastodon is only superficially a Twitter replacement. Underneath a familiar microblogging interface, Mastodon is a part of the Fediverse, a distributed, community-driven infrastructure that hearkens back to the early days of the Internet, when our lives weren’t ruled by tech giants. It can take a bit to get started with Mastodon, but the friendlier community and lack of drama may be worth it. Also this week, Apple finished off its latest operating system release by pushing out tvOS 16.3 and the rather interesting HomePod Software 16.3. Our ExtraBIT this week points you to the acknowledgment from GoTo that data stolen in the breach of its LastPass subsidiary also contained sensitive information about GoTo users. Notable Mac app releases this week include Affinity Designer, Photo, and Publisher 2.0.4, BusyCal 2023.1.1, MarsEdit 5.0.2, and Lunar 5.9.5.

Apple Releases HomePod Software 16.3 and tvOS 16.3

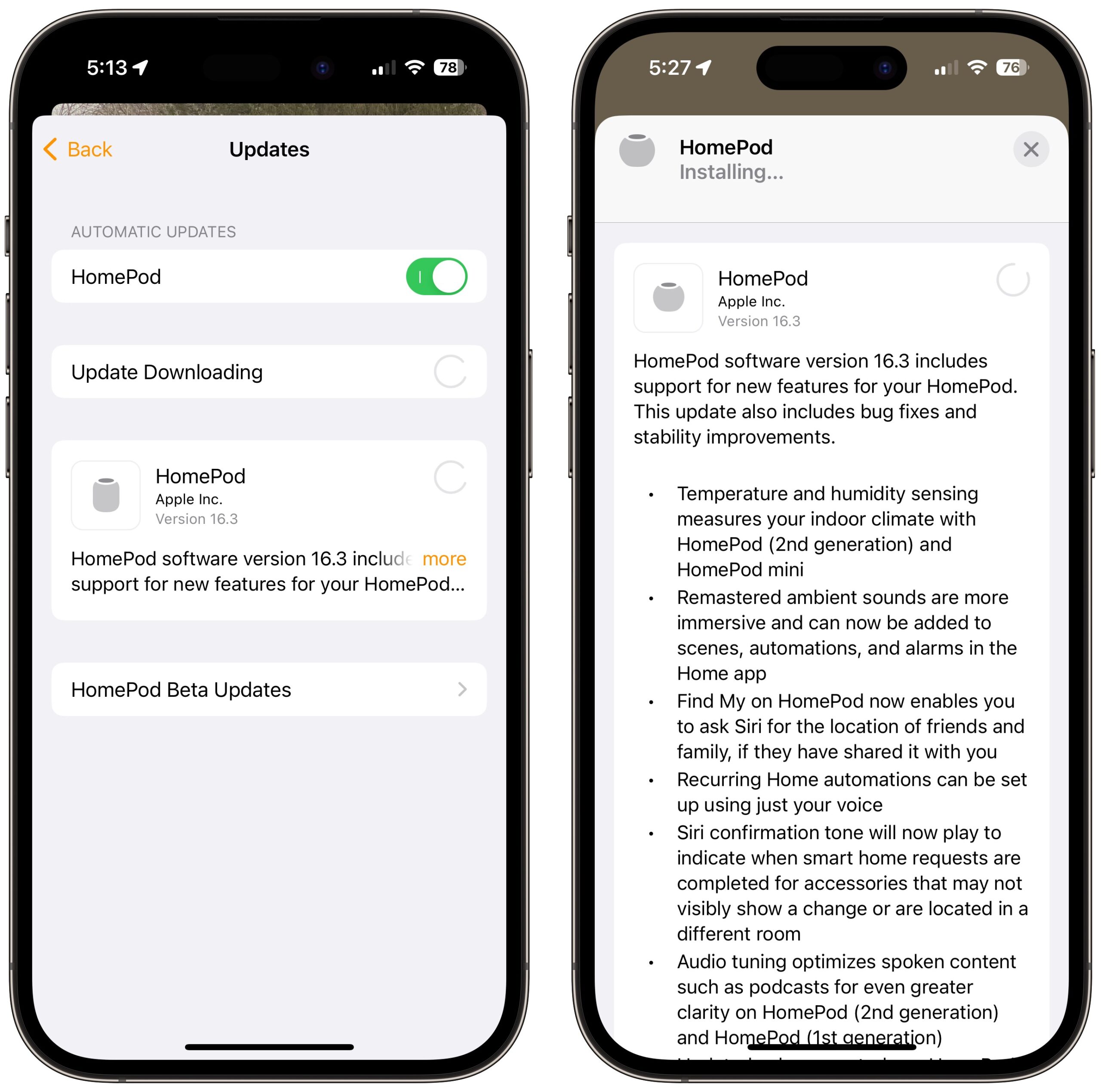

Apple’s release machine took a brief break before unveiling HomePod Software 16.3 and tvOS 16.3 (see “Apple Releases iOS 16.3, iPadOS 16.3, and macOS 13.2 Ventura with Hardware Security Key Support,” 23 January 2023). Those remaining two updates are now available, and while they are usually afterthoughts—and tvOS 16.3 remains one—HomePod Software 16.3 is actually quite interesting.

HomePods and Apple TVs generally update on their own, and I see no reason to prevent that. If you’re excited about one of the new features in HomePod Software 16.3, you could give it a nudge to make sure you get it right away.

HomePod Software 16.3

Although it’s unsurprising that HomePod Software 16.3 would include support for the just-released second-generation HomePod (see “Second-Generation HomePod Supports Spatial Audio, Temperature/Humidity Monitoring, and Sound Recognition,” 18 January 2023), it also has improvements that owners of the first-generation HomePod or HomePod mini will also appreciate.

For instance, Apple updated the volume controls on the first-generation HomePod to give you more granular adjustments at lower volumes. Both full-size HomePods benefit from new audio tuning that optimizes spoken content like podcasts for greater clarity.

The remaining changes are focused on smart home interactions and Siri:

- You can now take advantage of temperature and humidity sensing in the HomePod mini and second-generation HomePod to trigger Home automations.

- Remastered ambient sounds are more immersive, and you can now add them to scenes, automations, and alarms in the Home app.

- Find My on HomePod now enables you to ask Siri for the location of friends and family who share their locations with you.

- You can set up recurring Home automations using just your voice. I haven’t had a chance to test this, but I recommend double-checking the results in the Home app.

- HomePods will now play a Siri confirmation tone to indicate when smart home requests are completed for accessories that may not visibly show a change or are located in a different room. Currently, Siri confirms such actions with a voice response.

There are several ways to kickstart HomePod updates. I found that tapping the ••• button in the upper right of the iOS Home app and then selecting Home Settings > Software Update caused all three of our HomePods to start downloading the update. I presume it would have installed on its own, but I gave it a push by pressing a HomePod tile in the Home app, selecting Accessory Details, scrolling down (or tapping the gear icon) to reveal the necessary controls, and then tapping Update.

tvOS 16.3

Not a lot to see here, folks. With regard to tvOS 16.3, Apple merely says that it “includes general performance and stability improvements.” It also includes fixes for 10 security vulnerabilities. Let it install on its own.

Is Your Future Distributed? Welcome to the Fediverse!

A new concept with old roots has started to come to the fore on the Internet: federation. Instead of a centralized system, typically run as the equivalent of a single giant database by a company with a profit motive or investors to repay, federation relies on distributed servers. Each server, called an instance, runs a common protocol. Servers using that protocol agree to exchange nuggets of information, like brief posts or pieces of media. The best-known and most popular example of a modern federated system is Mastodon, a micro-blogging network that has garnered great attention as the primary alternative to Twitter. (See this article’s sibling, “Mastodon: A New Hope for Social Networking,” 27 January 2023, for more about the ins and outs of what Mastodon is, why you might join, and how to use it.)

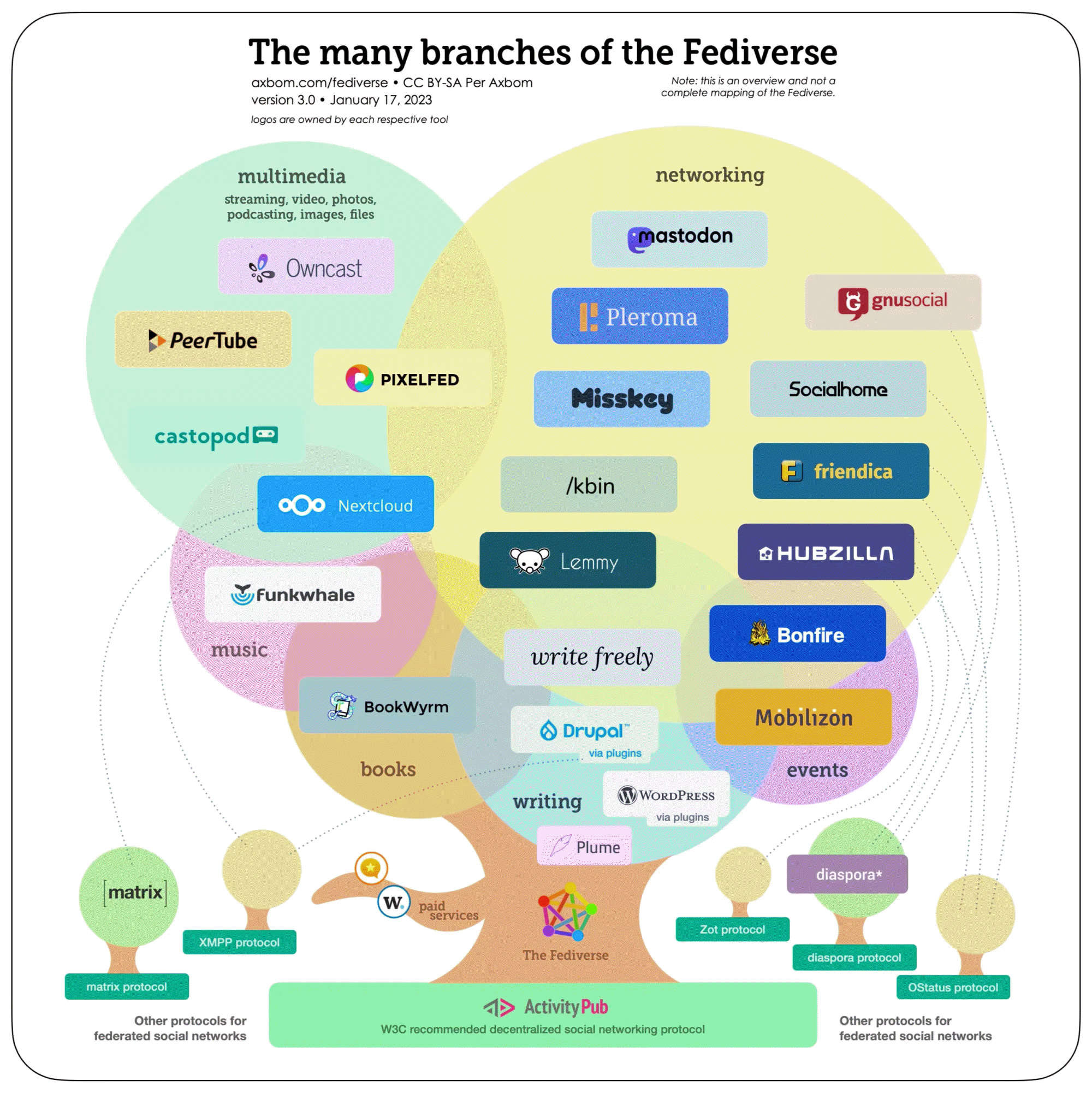

The concept of federation has garnered recent attention because of the rise of the Fediverse, a set of open-source protocols that manage user activity on a server and the interchange of information among users on other, independently operated servers. (The most widely used such protocol is ActivityPub, supported by the World Wide Web Consortium, but there are others.) Server software—typically open-source as well—supports federation by allowing users to register accounts locally, then letting local users follow and be followed by users on both the local server and other servers within the Fediverse that run the same protocol. In essence, this open-source system builds a skein of connections across servers that don’t have to make prior arrangements to interact.

There’s no center of the Fediverse. Each participant and each server has their own agenda, operating principles, and local data store. The connections among servers are all consensual, voluntary, and subject to change. No authority dictates whether a given server can or can’t connect to another; nor can an overarching authority demand that users or content be removed. (Governments and courts are another matter, but they are always extrinsic actors with regard to individual or commercial speech.)

You can find Fediverse software for exchanging music, social networking, and photo and music sharing, among many other purposes. This nifty site—non-authoritative by its nature!—explains the Fediverse in depth and lists a huge array of Fediverse apps. I also love this graphic created last November by Per Axbom that visualizes many Fediverse apps as branches and leaves of a tree.

The Fediverse exists in stark contrast to most organizations’ centralized, commercial efforts to connect people via the Internet. It’s an example of the ethos of IndieWeb, which simultaneously looks back to the best of the Internet’s earlier days and forward to the best of what can be built today. The Fediverse is designed to share resources in a cooperative way that lifts all boats while also providing individual points of authority that decide how to connect to other independently operated networks and servers.

While your immediate interest may primarily be Mastodon—and for that, see the article linked above—the Fediverse is broader, a galaxy in which Mastodon is the language of peace among many star systems and trade routes, while co-existing with many other federated systems. Let’s dig into what the Fediverse is and what it means.

Back to the Future of Non-Centralized Interactions

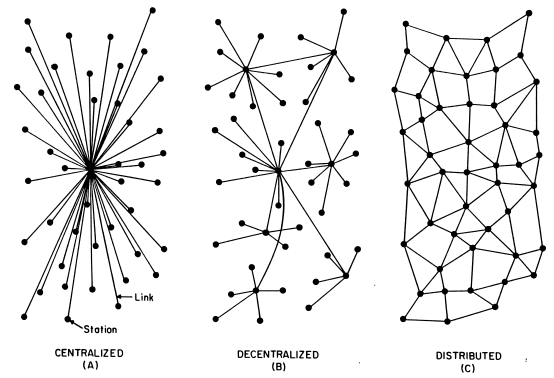

In the universe of possibilities of how people communicate electronically with one another, the choices largely separate out into centralized, decentralized, and distributed. This is not a new distinction, as you can see in this network types diagram from an influential 1964 research paper by Paul Baran.

Here are the definitions with services as examples:

- Centralized: Twitter is centralized. One company owns the protocol, data, and servers. It manages the accounts, sets policies, and has total control over advertising, what’s posted, who uses the service, and how third parties can access the data. (To wit: Twitter’s abrupt banning of third-party app access to the company’s API with no notification—see “Twitter Bans Third-Party Client Apps,” 20 January 2023.) The center is the truth: the only place to interact with the abstract notion of what the service is.

- Decentralized: DNS is decentralized. There is a hierarchy for the domain name system, which defines how parts of the Internet can be discretely named and associated with network IDs and other data. Certain resources in the domain name system are operated by central authorities who set some policies and operate many critical technical resources and servers. These authorities hold certain truths, like which servers hold the lists of .com and .org domains. Despite all that, within fairly loose constraints, anyone can host or delegate hosting of a domain name that they own, choosing all the associated values like subdomains, mail servers, site validation text entries, and so on.

- Distributed: The Fediverse is distributed. Each Fediverse instance is its own Little Prince world that can choose to engage with other servers through federation, the interchange of information stored locally with other servers remotely. There’s no one in charge and no single place to go for definitive truth about the network.

The oldest among us might find this reminiscent of what used to be called store-and-forward systems, like the original FidoNet, UUCPNET, and BITNET. These were early examples of a kind of federation. Every server knew how to pass information destined for non-local accounts, even if that merely meant passing it along to the next server. With UUCP, for instance, mail could be addressed using bang routing, which listed out each server between the source and the destination. These networks were critical in the early days of internetworking when modems were expensive, bandwidth scarce, and no backbone existed.

Centralization is, by definition, in opposition to that spirit. It spread partly because of the cost of resources required to manage the necessary computational and bandwidth requirements as the Internet grew richer in media and more complicated. The technical bar to entry also deterred mass adoption. Newer services provided an easier on-ramp to some components of the Internet, and social networks captured audiences who primarily used email and a browser, and didn’t want to blog, build a Web site, or post on Usenet.

Something that charts a new course on old paths has to demonstrate a thriving community, provide easy access, and work reliably. It’s hard to argue that all three of those exist today in the Fediverse, but each of those elements is heading in the right direction.

Mastodon and the Fediverse represent something far better than Web 2.0—and vastly better than what’s already seen as the ill-fated, ridiculously branded metaverse/crypto-focused Web3. The Fediverse is more like Web 1++: what you liked back in the early days, only modern and much more of it.

The Limits of Federation

Federation has some drawbacks related in part to the lack of a central organization that handles infrastructure and policy. That said, these drawbacks are really all two-edged swords, with both negative and positive aspects:

- Instances choose which other instances to federate with. There’s no way to force an instance to exchange messages with every other instance. An instance you’re on may block lots of others for trivial reasons. Generally, that’s not the case because capriciously run instances wind up only with users who strongly agree with those capricious decisions (which sounds a lot like Twitter these days).

- Instances that are media-heavy, user-heavy, or interaction-heavy may have higher server and bandwidth costs than less-loaded instances—perhaps thousands of dollars per month instead of just a few dollars a month for a smaller instance.

- The admins who run an instance have a burden of moderation to ensure users on their instance are happy and that the instance isn’t engaged in activities that violate the law. In the US, instances also have to be responsive to Section 230 requests, legally binding demands to remove reported content immediately.

- Most instances are run by an individual or small group volunteering their time and donating their money. Few involve paid staffers. Thus, every minute an admin or moderator spends dealing with something structurally, socially, or legally wrong is time stolen from something else they could be doing.

- ActivityPub, the underlying protocol, wasn’t designed to be efficient in the face of massive interconnections among servers. This can lead to long delays in message propagation. However, because ActivityPub is open source, developers are actively working to improve efficiency.

You might recognize some of these problems from email, which is effectively a federated service despite the massive numbers of consumer and business email accounts hosted by Apple, Google, and Microsoft, as well as for employees by large corporations. For instance, the admins who run email servers can and do block mail from going to or being received from other email servers; constantly updated lists of bad actors aid that process. Individual email recipients can use tools to block messages from individuals or entire domains. (In contrast, admins of federated servers may have to examine individual messages constantly, something that’s rarely done with email). Email used to suffer from limitations on email attachment size and volume of messages sent, sometimes resulting in huge backlogs in receiving email. These issues have subsided over time as the costs of bandwidth and running servers have dropped.

Despite these problems, email has thrived. Turn-of-the-century predictions that email would become increasingly balkanized, with servers interacting only with subsets of other servers, didn’t come to pass. One specific worry was that any given email message might not be able to get from here to there, wherever there was, because of a block in between. That hasn’t happened. The success of email as a decades-long experiment in federation should give us hope.

In the Fediverse, most instances do block other instances. But it’s typically a subset of other instances for various bright-line reasons. The most common are instances used by people with extremist ideologies. This so-called defederation—blocking traffic from another instance—happens at the discretion of the admins of an instance. Within Mastodon, in particular, you can also mute or block accounts or entire instances aside from the instance on which your Mastodon account is hosted. You then will never see that individual or posts from that instance.

Admins can also take various moderation actions against individuals and posts or other items. In the Mastodon world, some instances have a robust moderation team and a detailed acceptable use policy. Some even have a review board or advisory group to ensure fairness and offer recourse. Moderation doesn’t benefit from scaling, making it a challenge as the Fediverse grows. An increase in users and activities could result in the heavy-handed removal of posts and people or insufficient throttling of bad actors. That, in turn, could lead to other instances being defederated from an instance that is either too severe or not severe enough!

Fortunately, while every account must live on a particular instance, you own your social graph, your connections with other people. You can migrate your identity from one server to another, bringing followers and those you follow along, and leaving behind an automated forwarding address. (With Mastodon, your posts don’t migrate but remain in amber on the previous server unless an admin there removes the account.) If you’re blocked or banned on the instance where the account you want to migrate lives, that naturally introduces complexity.

If a given Fediverse project, including the underlying ActivityPub protocol, became too radical in its behavior, it could be forked, or become a duplicate of the project taken in a new direction, because most of these efforts are open source. People running instances that use a protocol could opt to install the forked version if they didn’t like the primary direction. This could split up the Fediverse or a service within it, but in practice, most forks don’t deviate far from the primary branch.

Not all apps compatible with the Fediverse are dedicated to it. For instance, Manton Reese’s Micro.blog service supports ActivityPub as a format and enables it by default on accounts created starting in October 2022. In Mastodon, you can add a Micro.blog user’s feed as easily as adding another Mastodon user. WordPress users can install an ActivityPub plug-in (in beta) to allow similar feed subscriptions. The Fediverse is also highly flexible around RSS, using it as a sort of lingua franca to obtain non-interactive feeds.

Is the Future One in Which Divided, We’re United?

The future of the Fediverse isn’t dependent on mass adoption by hundreds of millions of people. No company has to pay thousands of employees or maintain massive server resources. Instead, it’s predicated more on momentum and commitment. Open-source projects and volunteer-run servers require people who believe what they’re doing is worthwhile, whether from enlightened self-interest or generosity.

The excitement over the Fediverse is that we could see the blossoming of a dream held in the equivalent of an Internet seed vault for nearly two decades, thanks to the current focus on Mastodon. As blogs died, RSS receded, and people owned less of what they posted and their relationships with others, the question was whether the seeds of the dream of a distributed Internet would die ungerminated. The Fediverse is fresh soil. Let’s see what blooms.

Mastodon: A New Hope for Social Networking

Cast your mind back to the first time you experienced joy and wonder on the Internet. Do you worry you’ll never be able to capture that sense again? If so, it’s worth wading gently into the world of Mastodon microblogging to see if it offers something fresh and delightful. It might remind you—as it does me, at least for now—of the days when you didn’t view online interactions with some level of dread.

Mastodon isn’t a service but a network of consensually affiliated, independently operated servers running the Mastodon software. It’s the best-known example of the so-called Fediverse, and it has seen a huge uptick in users since Elon Musk purchased Twitter and began firing workers, breaking systems, blocking third-party Twitter apps, and restoring access to accounts suspended for a variety of antisocial, fascist, and anti-democratic behavior. (For insight into the Fediverse, see my sibling article “Is Your Future Distributed? Welcome to the Fediverse!,” 27 January 2023).

At the surface level, you might mistake Mastodon as a mere Twitter replacement. Yet it’s more complicated than that, in a good way. Mastodon has received disproportionate attention in the last few months because it offered the closest comparable refuge for people who found Twitter intolerable but wanted to retain online social ties. In early 2022, only a few hundred thousand people had registered accounts on Mastodon servers; that number jumped to about 2.5 users by November 2022 and currently exceeds nine million. In comparison, Twitter boasts hundreds of millions of accounts, though one of Elon Musk’s most verifiable pre-purchase criticisms was that Twitter may have a huge number of bot-driven accounts devoted to spam, scam, and hype.

With Mastodon, you’re not dealing with a giant, faceless company—or a constantly in-your-face CEO—making arbitrary decisions that are often impossible to understand or appeal. Instead, you join a Mastodon server—called an instance—run by an individual, company, or organization. Each instance exchanges messages, or federates, with other Mastodon servers. Servers pass packets of content based on the social graph of which users subscribe to other users’ posts. No central database of posts exists, nor is there a central repository of social graphs. Mastodon exists entirely of its parts—there’s no core Mastodon server or entity.

You can think of Mastodon as a flotilla of boats of vastly different sizes, whereas Twitter is like being on a cruise ship the size of a continent. Some Mastodon boats might be cruise liners with as many as 50,000 passengers; others are just dinghies with a single occupant! The admin of each instance—the captain of your particular boat—might make arbitrary decisions you disagree with as heartily as with any commercial operator’s tacks and turns. But you’re not stuck on your boat, with abandoning ship as the only alternative. Instead, you can hop from one boat to another without losing your place in the flotilla community. Parts of a flotilla can also splinter off and form their own disconnected groups, but no boat, however large, is in charge of the community.

If you’re a regular Twitter or Facebook user—or avoided both those and similar services—and want to understand what Mastodon is, where it seems to be headed, and how to join in, read on. You don’t need a lot of technical details to understand why Mastodon and the Fediverse exist in sharp contrast to commercial social networks and why they hearken back to some of the more enjoyable aspects of earlier stages of Internet interactions.

And keep in mind that things change. Mastodon is an active project under development, with ships of new participants joining the fleet daily, many asking for new features. When you join Mastodon, you’re part of a journey in which the details of where you’re going and how you’ll get there are still coalescing.

What Is Mastodon and How Does It Work?

Mastodon is an open-source project that uses the elephant’s extinct sibling species as its mascot. A non-profit German company manages the effort and runs some large Mastodon instances. The network is part of the Fediverse, a set of software projects that use the same set of account and interchange protocols—mostly ActivityPub—to manage local users and exchanges of data between local users and remote servers. Unlike Twitter, where there’s a central store of user account names and tweets, Mastodon and Fediverse services are local in nature and global only in some interactions.

As a Mastodon user, your perception is that everything is unified. Admins and protocols manage the ugly business of ensuring communications move seamlessly across federated instances.

While Mastodon seems complicated from the outside, I’d argue that if you can set up an email account and have signed up for email lists throughout your time on the Internet, you can settle into Mastodon fairly quickly. In many ways, Mastodon even resembles email, albeit with more of the plumbing exposed:

- Your account is hosted on a single server. While you can have accounts on different instances, each is treated as a separate address across the Fediverse.

- People can find you and address messages to you in the form

@[email protected]; my Mastodon account is@[email protected]. (I had an older account that I set up years ago,@[email protected], which I essentially redirected to my current one. If I had kept it, I would need to check messages on it separately, just as if I had email accounts on different servers.) - Messages are stored locally before being transmitted elsewhere, if they need to go off-server.

- Admins are responsible for keeping an instance running and may choose which other instances they federate with—or refuse to interact with. (Think about blocklists for email servers that only send spam or harassment.)

When you use a Mastodon app, you log in to the server hosting the instance for your account. When you post in Mastodon, your text and any affiliated media and metadata are stored locally on that instance’s server, too. People whose accounts are on the same server or view a local feed see your post retrieved from their local data store.

The federation aspect comes into play as you build what is known as a social graph: the connections between you and other people. You follow people who post interesting things, and people who find your posts interesting follow you. (A Mastodon app typically handles the complexity of knowing which instance they are on.)

Your instance knows which other instances have users subscribed to you and vice-versa. Whenever you post, your instance uses ActivityPub to push that post to every server with a subscribing user. The same happens in reverse. Think of it like an email list but for servers rather than individuals. As Effy Elden, an infrastructure consultant at Thoughtworks in Australia, explained on a podcast:

Every time [a particular user with 6000 followers] posts, that essentially creates a thousand jobs, a thousand tasks for our server, which is to go out and push that out to actually make a web connection to each of those remote servers and deliver that, post that status. All of that is done asynchronously…

The asynchronous part means your post is handed off to agents on the server that perform the actual distribution. ActivityPub wasn’t designed with the current scale of Mastodon in mind, and these agents can sometimes get hung up if they lack the processing power or if other instances are overwhelmed. You can see propagation delays across the Mastodon network, which usually doesn’t happen or isn’t obvious with Twitter and other centralized systems. However, delays ebb and flow, typically clearing up after masses of new users join Mastodon and admins spin up more servers or add more resources. And, let’s face it, how much do you really care if a post takes a few minutes longer to arrive at your instance?

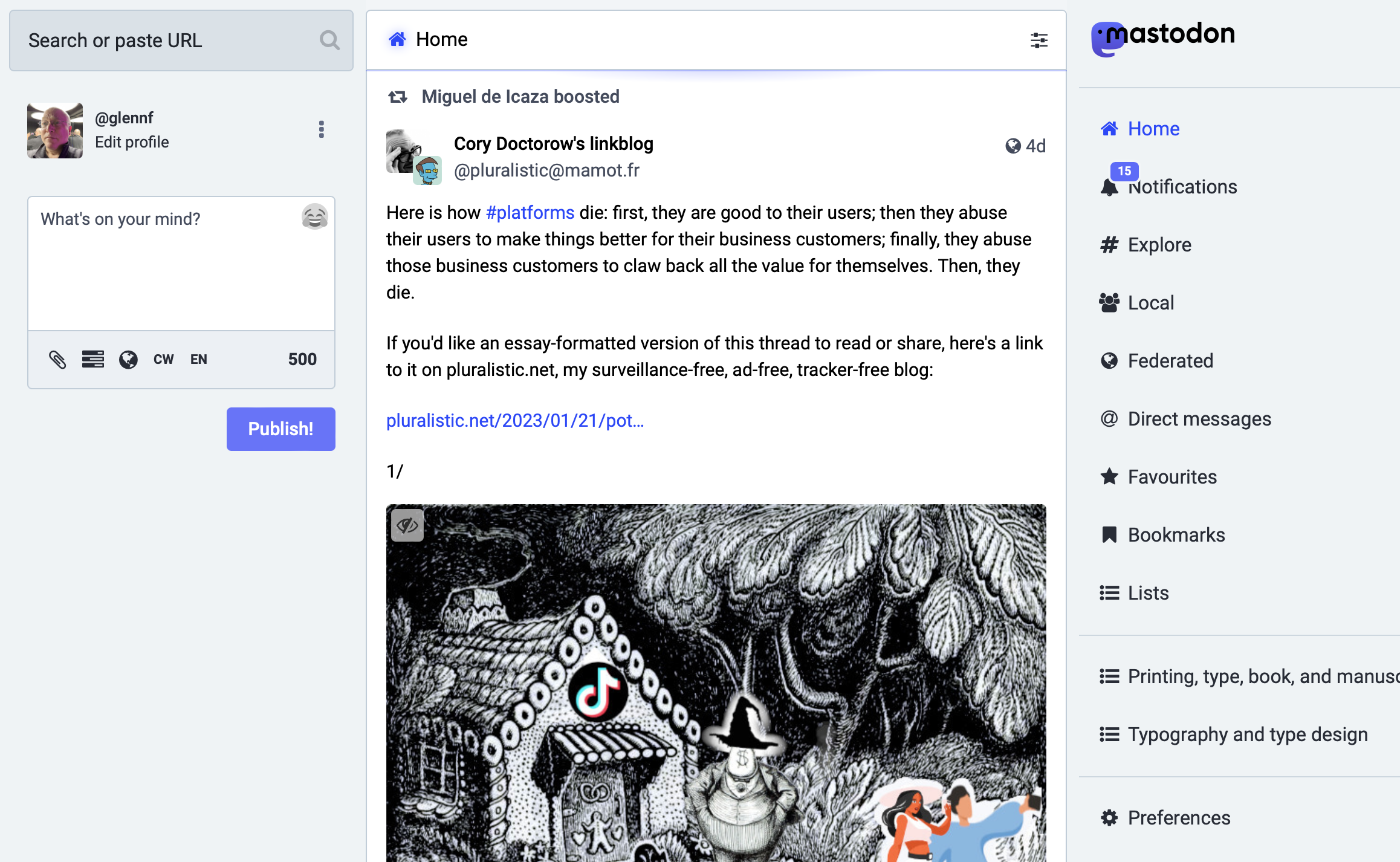

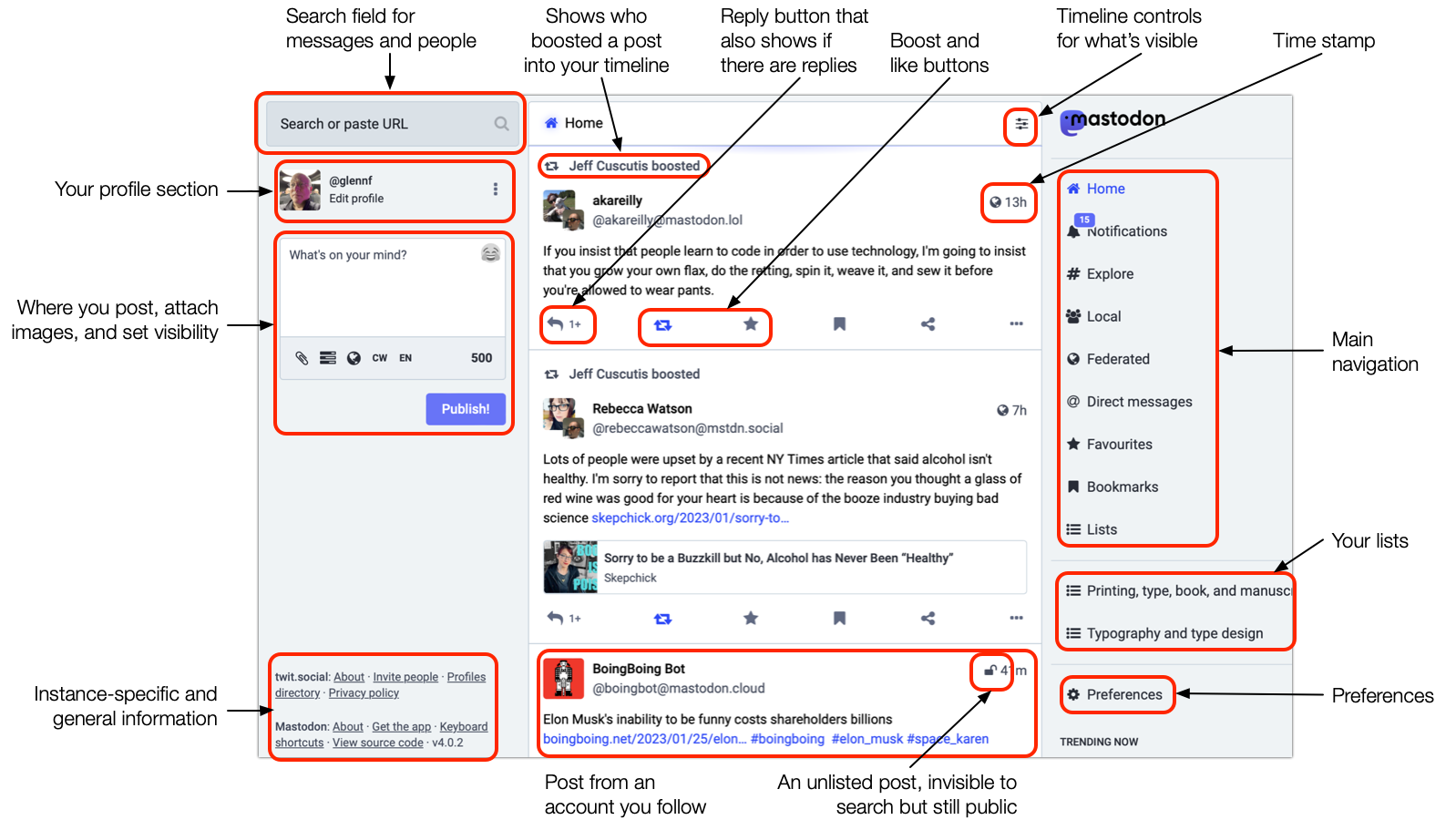

Mastodon offers a standard Web app as the front end for your account, shown below. The Web app offers a large amount of functionality. Developers have created mobile and desktop apps for every platform. (It’s hard to call them “third-party” apps when all parties are in a position of equality.) Unlike centralized networks, Mastodon’s API—the hooks into its system—is open to everyone, with no restrictions on what functionality and value they can add.

That’s the background. Now let’s get cracking on how you can join the Mastodon network.

How To Sign Up for Mastodon

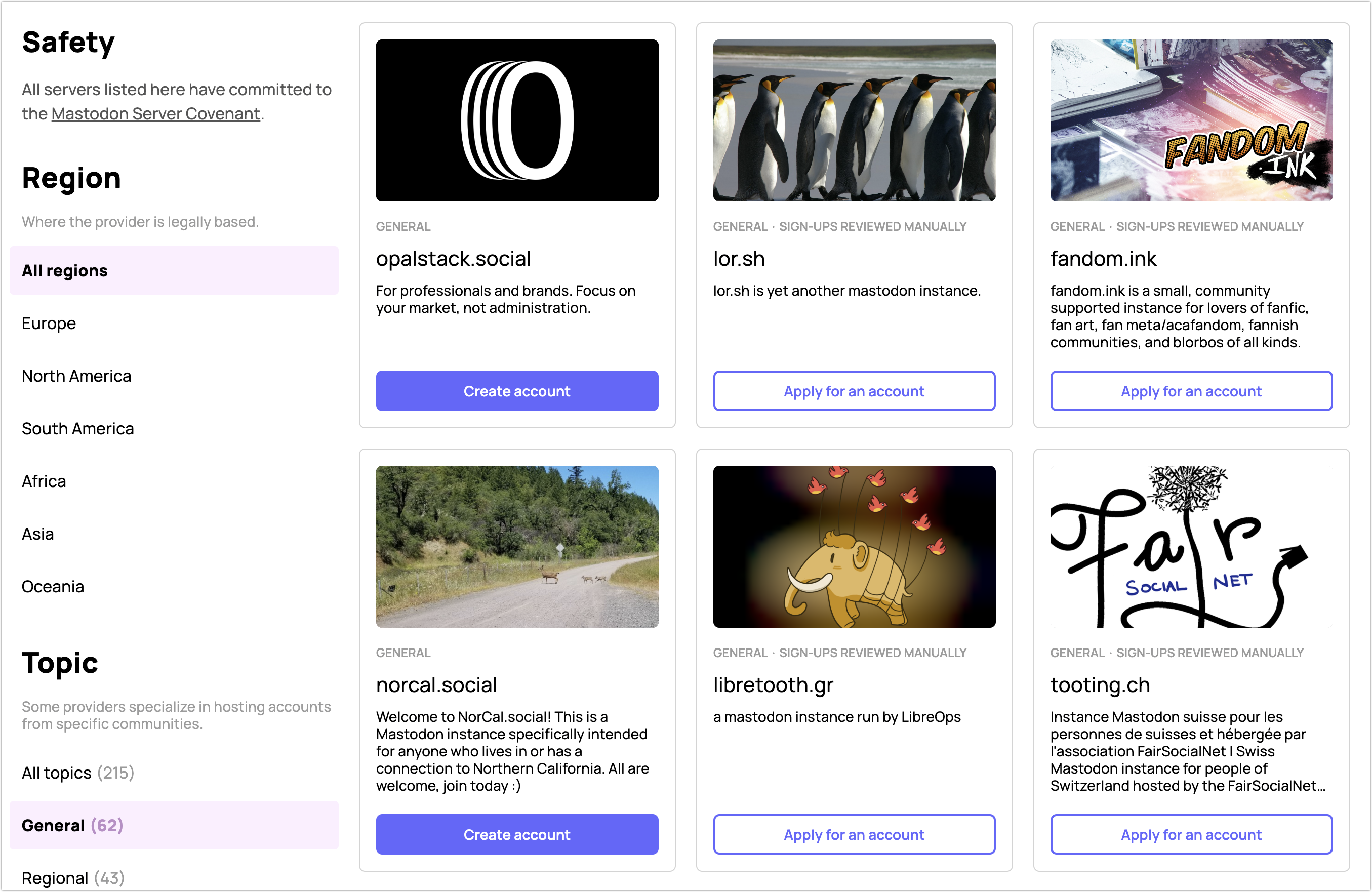

Because there’s no center of Mastodon, the process of getting up and running can be confusing and frustrating. It’s harder than picking an email server because there are so many choices, nearly all of which are free to join when they have the capacity to add more users.

Choosing from Apple, Google, or Microsoft for email is easier than picking from hundreds of Mastodon instances. However, in recent weeks, the Mastodon project has improved its landing pad, as its site is often the first place people arrive when searching on Mastodon.

If you go to Mastodon’s home page and click Servers, you see a list of instances accepting users. As I write this, the list has over 200 entries. All instances on the list commit to a few basic principles, including moderating against hate speech. Some let anyone sign up; others require that you apply for an account.

Finding one can feel daunting! Here’s how you can narrow your choice:

- Just tell me where to join! Many people go straight to Mstdn.social. When you click Create Account, Mstdn.social provides a straightforward set of expectations.

- I need some guidance: Under Topic, click General. There are dozens of servers in this list, but most have a particular focus by geography or subject matter.

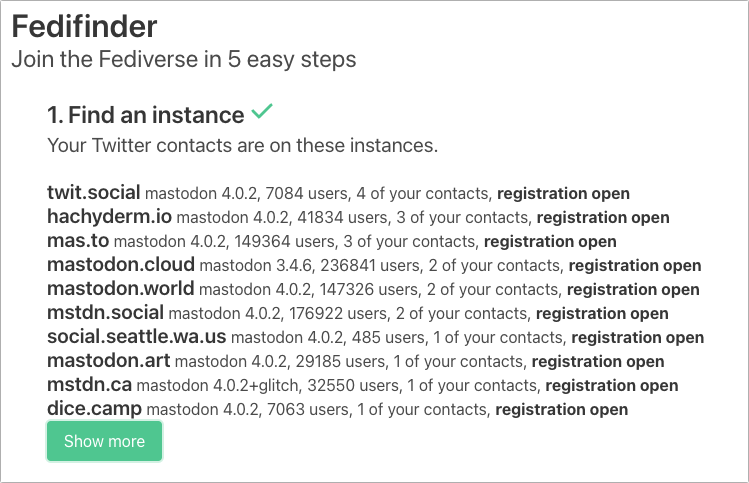

- I want to move to an instance where most of my Twitter friends are hosted: The Fedifinder app scrapes Mastodon accounts from the profiles of everyone you follow or who follows you on Twitter. After scanning, it shows you the instances used—in order of most to least—by folks on your list and which are open to new members. (Use it after joining, too, to populate your Mastodon account with followers, followed, or both.)

- I’d like to be part of a specific community and have an account instance name that shows it: Search for regions or topics to find one that conforms with your preferences.

- I’m concerned about where my data lives and want it to be in Country A or not in Country B: You can filter the list by country and read policies on an instance’s about page or through other links on their site to determine how they conform to data privacy and legal requests.

Instances may emphasize a particular community and could require that you demonstrate that you’re part of that community, like living in a country or being an ex-pat, an artist, or a working journalist. Others are less strict or take all comers.

This may make joining an instance feel like joining a club, a Discord server, or an Internet forum. But it’s really much looser. One way the instance you choose makes a difference is that you can browse a Local view on Mastodon that shows public posts only from other users of the same instance, plus less-public ones from people you follow locally.

However, the most profound issue with joining an instance is that moderation policies and the exercise of moderation often align with the intent of the instance. For instance, the tech.lgbt instance is aimed at “tech workers, academics, students, furries, and others interested in tech who are LGBTQIA+ or Allies.” In conjunction with the kind of abuse, *-phobia, and other forms of antisocial behavior that people in a community like this often experience on other social networks, tech.lgbt has a lengthy code of conduct that starts with a summary of purpose and goes into detail. That means this instance is more likely than others to throttle routine harassment, which could involve moderation or bans against posts or users on the server, or blocking posts, people, and entire instances from appearing or federating.

Many admins accept or solicit donations to cover operating costs. Some offer full transparency on costs and revenue, such as Mstdn.social, which has a page containing its budget. I expect that, over time, we will see more for-fee instances that use revenue for a more consistent experience and for paid administration and moderation help. It’s also likely that more membership organizations will add a Mastodon instance as a benefit of being part of the group—that’s what Leo Laporte of This Week In Tech has done with the twit.social instance for Club TWiT members.

With an account to hand, you can now start following interesting people and make your own posts! (You can read public posts at some Mastodon instances without an account, but you’re highly limited in how much you can see across the federated set of instances.)

How To Use Mastodon

You can simply use a Web browser to navigate to your instance’s URL and log in. The Web app is not bad! In the discussion that follows, I’m using the Mastodon Web app because nearly everyone has access to it as a starting point.

You can also get a third-party app, which the Mastodon project tracks. This includes Tapbots’ Ivory, built on the framework the company designed for the late, lamented Tweetbot, one of the most popular Twitter clients. (Ivory was in alpha testing when Twitter cruelly and without notice pulled the plug on third-party Twitter apps. Tapbots moved quickly into “save the company” mode and produced a 1.0 version of Ivory that works quite well, with a public roadmap of features to come.)

If you have an active Twitter account, there’s a way you can bring some of the people you follow (or who follow you) over to Mastodon. This requires a third-party app that you authorize to scan your Twitter account. (Such apps still work, but it’s hard to believe that will last long.) I recommend Fedifinder, as noted earlier. When it completes its operation, you can “click Export CSV with found handles,” save the file, then import them as a “merge” (not “overwrite”!) to your Mastodon account. I brought over several hundred people I follow that way and am pretty sure I was added by many more through Fedifinder or similar tools.

As you settle into Mastodon, you can use two views (look in the Web app’s sidebar) to help find people you might like to follow: Local and Federated. Local shows all public posts from the instance you’re on; Federated offers a timeline of all public posts across everyone followed by everyone on your instance!

As you see entries in your timeline, note that there’s no “engagement algorithm” or other tool to sort messages by a priority best understood by a social-network operator. Instead, posts appear in reverse chronological order, newest first. We’ll likely see clients that offer other options, such as prioritizing people you follow.

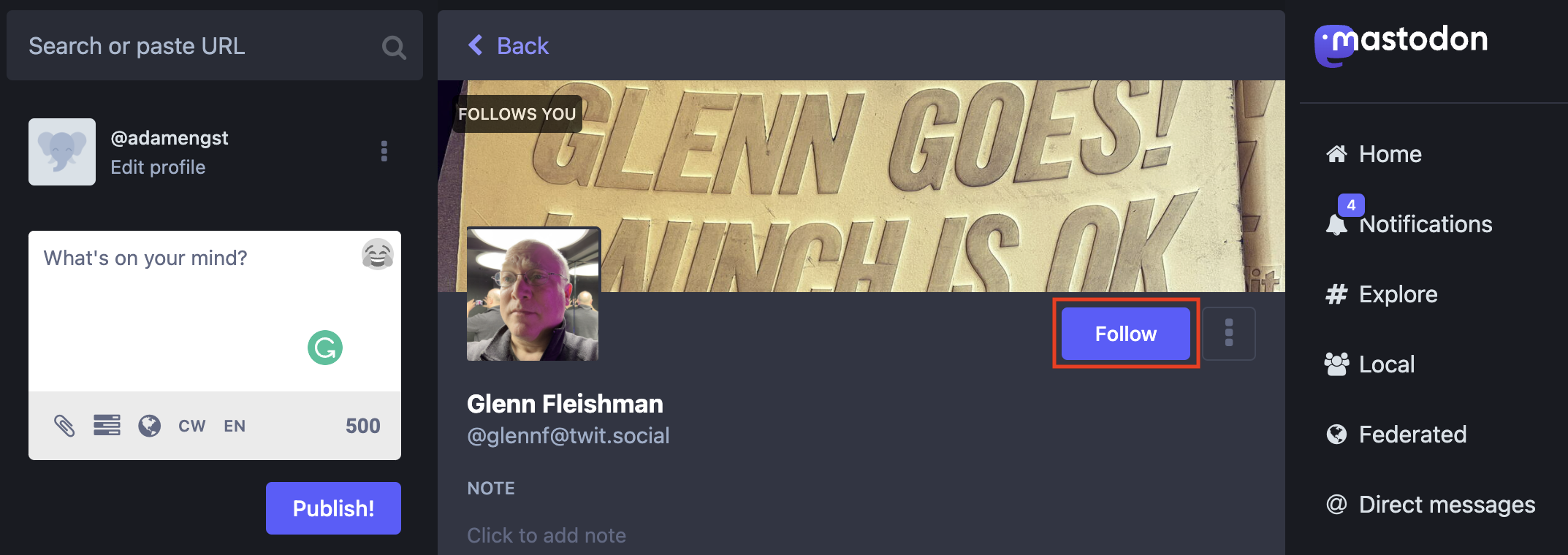

To follow other Mastodon users, use one of these methods:

- Click their name, which is a link to their profile, then click Follow.

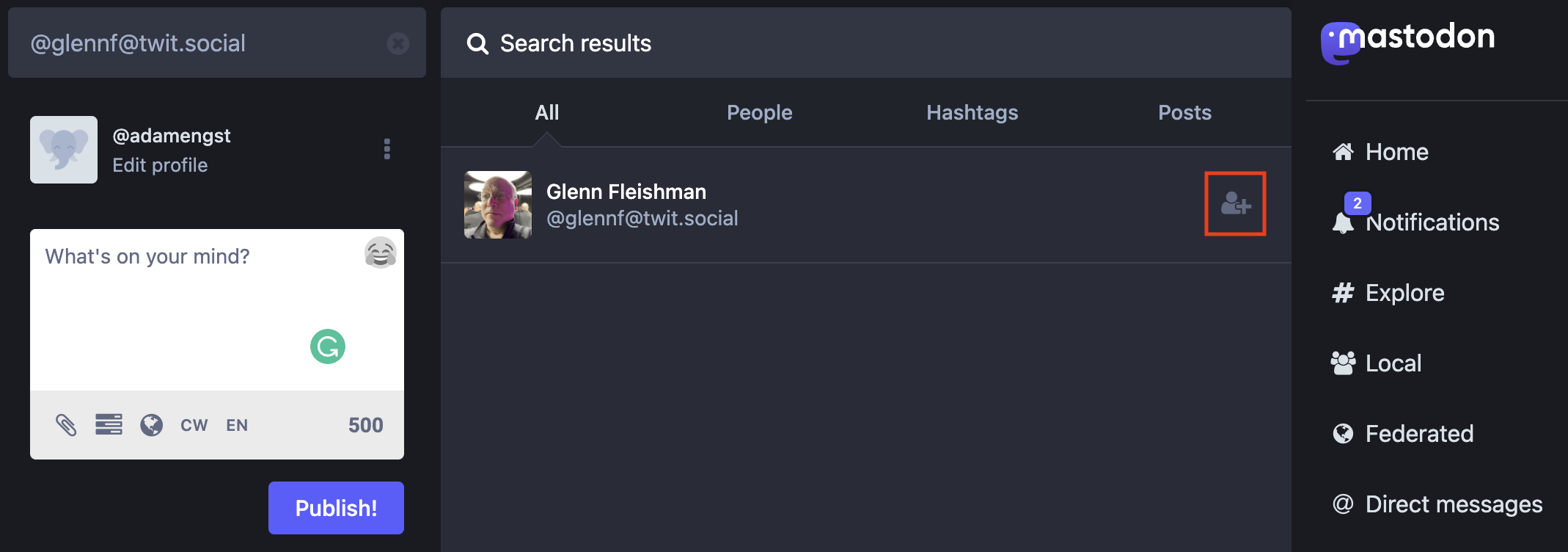

- Copy their Mastodon address in the form

@[email protected], paste it into the search field, and press Return. For me, that’s@[email protected], or you can follow Adam Engst at@[email protected]. You then click the “person plus” icon to the right of their search result to follow them.

- Instead of an address in the Fediverse format, you can paste a full URL, like

https://twit.social/@glennf, into the search field at the top left to get the same result.

I recommend fleshing out your profile right away so people know who you are. You can click Edit Profile in the upper-right corner of the Web app and then add a photo or avatar, a profile background, a biography, and links. There’s no such thing as a private account in Mastodon, but you can check a box to require approval of all followers, as shown below, and post in a semi-private manner that I explain later.

Because Mastodon is distributed, no one can validate your identity as such. But you can use a technique that lets you prove you have a relationship with a Web site that you add to the “Profile metadata” section. On any site you link to, if you can add HTML on the page, you can add a rel=me tag, a sort of self-verification confirmation. You can click next to the metadata to copy the right format with your handle, which looks like <a rel="me" href="https://twit.social/@glennf">Mastodon</a>. The Mastodon part isn’t needed: the link can be empty—I always remove it. Once you add that snippet, the link will validate and appear green to you and others on your profile.

When you’re ready to post a “Hello, world!” message, consider writing a message you tag with #introduction. Tell people a bit about yourself. You can pin this message after posting so it appears as the first thing if someone goes directly to your profile.

When posting, consider the following:

- Length: Messages can be up to 500 characters long on most instances. Some admins have opted to make their maximum message length longer. I’d argue that above 500 characters, you’re moving from microblogging into regular blog length, but opinions vary. Some Mastodon clients, like Ivory, show just the first 500 characters and offer a “more” link to view the rest.

- Post visibility: Mastodon offers four ways to control your post’s visibility: Public, Unlisted, Followers-only, and Mentioned-people-only. Public and unlisted posts are posted the same way, but unlisted posts can’t be found through discovery features like search. A Followers-only post does what it says on the tin: it’s visible only to people who follow you. If you restrict followers, that is the closest thing to a private account post possible on Mastodon.

- Direct messages: The Mentioned-people-only post visibility option is how Mastodon implements direct messages between individuals. (Direct messages also get their own tab in the Web app.) Mastodon users and the Mastodon software warn newcomers that DMs aren’t end-to-end encrypted, so admins on any server through which the message passes could read them. That’s true for Twitter, too—it’s just that everyone who works at Twitter with the right level of permission can read everyone’s DMs. (A pass at the work to make Mastodon DMs fully encrypted is done but not yet deployed.)

- Content warning: You can add a content warning to any message. Some people use this as a place to put keywords around topics that people might require preparation to encounter, like suicide, war, or racism. Others use the content warning field as something akin to a subject line. Still others ignore it. For instance, a vibrant debate is underway on Mastodon over whether putting “racism” in a content warning is a way to let people who don’t experience that societal ill avoid discomfort as opposed to allowing those who are the subjects of bigotry to skip posts that could add to their trauma. There’s clearly no right answer, only continuous discussions.

- Accessibility: Mastodon culture has long emphasized accessibility. That’s reflected most strongly in the easy option to add a description to images you attach to a message. You can add up to four images. In the Web app, click Edit next to an uploaded image’s preview and either type in a description or use a text-recognition option that extracts text from the image.

- Hashtags: Hashtags are vital in Mastodon: there’s no global search engine! Hashtags are the closest thing you’ve got, and they only return results against messages in your instance’s Federated feed, not across all of Mastodon (if there’s even such a thing as “all of Mastodon”). You can follow hashtags just like you do people.

You can edit or delete posts on Mastodon after making them. Just as Apple did with iMessage, edited posts are marked as such so people reading them know they’ve been changed, and previous versions of the post can be seen. (This requires an instance running Mastodon 4.0 or later, released in late 2022.)

If you want to add details below your profile, you can pin a post. Click the ••• button and choose Pin to Profile. You can pin up to five posts before you must unpin posts to swap in new ones.

Mastodon automatically threads posts via replies, so when you want to respond to someone, click the Reply button to add your post to the thread for that message. Clicking the star marks a post as a favorite, something you can see in your Favorites tab (usually spelled Favourites; UK English spelling prevails in the Web app’s interface).

Mastodon offers an option to boost (like retweet) another user’s post onto your timeline. There’s no “quote tweet” equivalent yet, in which you can annotate a boost. There’s been a lot of discussion about it, and some approach will likely emerge. (The discussion has revolved around whether quote-tweeting encourages harassment or is a useful tool with equivalent good and bad uses as regular posting.)

Other users can see a total number of favorites and boosts on each message, along with public replies, including threaded entries. Mastodon’s system doesn’t track how many people see a post across the federation, as that’s impossible by nature and would be in opposition to its privacy- and local-oriented design.

Now that you know the basic mechanics, you might wonder, is Mastodon where you want to spend your online life?

Is Mastodon for You?

I started using Mastodon alongside Twitter in October 2022 and switched over entirely at the end of November, just before a long trip abroad. Each time Elon Musk made an odd or offensive move, or Twitter engaged in abrupt and often objectionable behavior—like suddenly pulling access for third-party Twitter clients without warning (see “Twitter Bans Third-Party Client Apps,” 20 January 2023)—Mastodon saw a new surge of people. By the end of December 2022, it started to feel an awful lot like my community back on Twitter.

The big differences? Mastodon has been quieter than Twitter because fewer people post in absolute terms. You never see posts from people you don’t follow pushed into your timeline by an algorithm or because someone paid for you to see it. The timeline is rarely event-driven: Mastodon isn’t designed to amplify messages but to spread them, so the kind of “Internet main character of the day” narratives that formed on Twitter around people thrust into the spotlight (for good or ill) don’t seem to happen. And there’s a noticeable lack of trolls you want to avoid. It was only a few days ago that I had the first truly objectionable account—one using an offensive caricature and speaking in a racially tinged dialect—appear on my timeline. I’m sure there are more, but between moderators clamping down on bad instances and bad actors, that kind of trolling and cycles of abuse don’t seem to have become problematic yet. (You can easily mute or block offensive accounts—or even whole instances—from your timeline.)

It’s possible that with more users, more negativity will spread, but it might not devolve into a horrible mess like on commercial services, which depend on “engagement” and thrive on posts that cause outrage. Moderators have a lot of power over their instances and federation with other instances. I’ve seen a lot of ongoing discussions about how moderators contact other instances about abusive users and what they do when they don’t get a response. It’s plausible that people who post merely to be a pain in the ass or spread harassment will get kicked off well-run instances and move to anything-goes instances, which in turn get defederated by well-run instances. There’s a lot that could go wrong, but so far, it’s largely going right.

There’s more talking with than talking at by far, and while it’s not always civil—that’s probably neither possible nor fully desirable—there’s a calmness and sense of control not present elsewhere. With nobody stuffing material down your timeline’s throat or constantly urging you to “engage” more, you set the pace for your own experience and curate it more closely to what you want.

I’ve been using Ivory for weeks, and it’s a transformative experience for using Mastodon because it’s familiar from my use of Tweetbot and was designed with the current flood of posts, favorites, and boosts that now occurs on the network. Previous Mastodon apps were largely built when traffic was far lower and were created by people volunteering their time and giving the apps away. Many of these apps have rapidly improved—some have released several updates in the last few months—and paid apps will likely soon offer features that require more full-time development to support. While I have already paid for a year of Ivory, you don’t have to pick it—or pay anything as long as you use the Mastodon Web app or one of the increasing number of free Mastodon apps.

It’s an interesting time to try something new. If you’re frustrated by Twitter or swore off social networks entirely, give Mastodon a spin. Among other things, it’s not designed to addict you—a huge improvement to start with. And as Mastodon grows and the Fediverse matures, we may find an Internet we thought was gone forever was just hibernating. Time to wake up!