#1665: Important OS security updates, abusive Web notifications, solve myopia with an iPhone, Self Service Repair

This issue’s biggest news comes in our shortest article. Last week, Apple updated nearly all recent versions of its operating systems to block serious security vulnerabilities that are actively being exploited by malware. Update everything soon. Prompted by reader requests, Adam Engst explains how to identify and eliminate abusive Web notifications that attempt to phish personal information from affected users. Adam also shares a neat trick for those who are nearsighted—did you know that your iPhone can stand in for your glasses in a pinch? Finally, Apple expanded its Self Service Repair program, but how many people are using it? Notable Mac app releases this week include Safari 16.5.1, CleanMyMac X 4.13.6, Mimestream 1.0.3, GraphicConverter 12.0.3, Pixelmator Pro 3.3.7, and Affinity Designer, Photo, and Publisher 2.1.1.

Apple Updates All Active Operating Systems to Block Exploited Security Vulnerabilities

Apple has updated all its active operating systems to address (in varying combinations) three security vulnerabilities, all of which are actively being exploited in the wild. The most concerning of the three vulnerabilities affects the kernel and thus cuts across all Apple operating systems, new and old. macOS, iOS, and iPadOS also receive fixes for a WebKit vulnerability, and iOS 15.7.7 and iPadOS 15.7.7 plug yet another WebKit vulnerability that has presumably been addressed in newer versions but afflicts versions prior to 15.7.

The affected operating systems include:

- iOS 16.5.1 and iPadOS 16.5.1

- iOS 15.7.7 and iPadOS 15.7.7

- macOS Ventura 13.4.1

- macOS Monterey 12.6.7

- macOS Big Sur 11.7.8

- watchOS 9.5.2

- watchOS 8.8.1

Neither tvOS nor HomePod Software are included at the moment. It’s possible the exploits can’t affect them, or perhaps Apple will release updates for them shortly as well.

iOS 16.5.1 and iPadOS 16.5.1 also fix a bug that prevented charging with the Lightning to USB 3 Camera Adapter. It must have been waiting in the wings such that it could hop a ride with this set of security updates.

Although it’s difficult to determine the severity of any given security vulnerability, Apple’s language about active exploits against new and old versions, coupled with the release of so many updates at once—even watchOS 8.8.1 for the Apple Watch Series 3—suggests these vulnerabilities are especially concerning. Update as soon as you reasonably can.

Apple Expands Self Service Repair Program; Have You Used It?

Apple announced it has expanded its Self Service Repair program to include the iPhone 14 lineup and the M2 models of the 13-inch MacBook Air and 13-inch MacBook Pro. Self Service Repair is also now available for M1 Mac desktops—the 24-inch iMac, the Mac mini, and the Mac Studio—along with the True Depth camera and top speaker in the iPhone 12 and iPhone 13 lineups.

In addition, Apple says it has simplified the System Configuration process necessary to authenticate genuine Apple parts, update firmware, and calibrate parts. Previously, users had to contact the Self Service Repair support team to run the final step of the repair; that’s no longer necessary.

I continue to find Apple’s messaging around Self Service Repair intriguing. Just read this bit from the announcement where Apple simultaneously pats itself on the back for its support of the Right to Repair movement and warns users against using Self Service Repair.

Self Service Repair is part of Apple’s efforts to expand access to repairs. Widespread repair access plays an important role in extending products’ longevity, which is good for users and good for the planet. For the vast majority of users who do not have experience repairing electronic devices, visiting a professional authorized repair provider with certified technicians who use genuine Apple parts is the safest and most reliable way to get a repair.

But perhaps that’s an accurate representation of the modern world, where a lot of people think they want to be able to repair their own devices and philosophically support the Right to Repair movement, but they don’t actually trust themselves to complete a repair successfully.

Have you taken advantage of Apple’s Self Service Repair program? How did it work out?

Solve Myopia in a Pinch with an iPhone

The discussion of how Apple’s Vision Pro puts a little screen in front of each eye reminded me of a neat discovery I made a while ago: if you’re near-sighted, you can use an iPhone to stand in for your glasses and even see in the dark.

Until several years ago, I wore contacts to correct my myopia, switching to glasses every night at bedtime. One night, after I had taken my contacts out, I realized my glasses were somewhere downstairs because I’d been traveling and hadn’t yet fully unpacked. Although I can see well enough to navigate the house—I’m fine with large shapes and colors—I would have had difficulty finding glasses on a table or counter, especially in a dimly lit room. Between the clear lenses and thin metal frames, there’s just not much to see.

That was when I had my brainstorm. I see perfectly at about a hand’s length from my face. Though problematic for everyday life, that’s helpful for close-up work on electronics or other small objects, and I also often read in bed without glasses using my iPhone, which is easy to hold at that distance.

My contacts were off, I needed to go downstairs to find my glasses, and my iPhone was at hand. I opened the Camera app and held the iPhone in front of my face so the viewfinder was in focus. Looking around with the iPhone blocking my eyes felt odd, but it worked like a charm. To avoid having to turn all the lights on and off (this was before I had wired them all up with HomeKit-compatible switches), I switched to Video mode, swiped up on the image to display the controls, tapped the Flash button, and locked the setting to Flash On.

With my ad hoc night-vision goggles in play, I walked downstairs and wandered around the darkened house until I found my glasses. For giggles, I even zoomed the view a few times to see something better than I would have been able to otherwise. I felt like a cyborg.

I haven’t needed to use the iPhone like this again. In 2020, I got tired of having to switch between multiple pairs of glasses over my contacts for reading, driving, and bright sunlight, so I got a single pair of photochromic progressive glasses that work for everything and are with me at all times. But I’ve always remembered just how well the iPhone hack worked and thought that if I was ever in a situation where my glasses were broken, it might be a lifesaver.

In some ways, the Vision Pro is the ultimate version of this hack, combining as it does forward-facing cameras and screens right in front of your eyes. Although Apple has optional Zeiss lenses for those who wear glasses, it’s unclear if they’d be necessary for those of us whose eyes focus at the distance of those screens. We’ll know eventually.

The idea isn’t new, I discovered. The 2015 research paper “ForeSee: A Customizable Head-Mounted Vision Enhancement System for People with Low Vision” by Yuhang Zhao (Tsinghua University), Sarit Szpiro (Harvard Medical School), and Shiri Azenkot (Cornell Tech) proposes a head-mounted vision enhancement system that looks like it’s based on an Oculus Rift headset. It doesn’t seem to have gone any further, though.

The closest I could find to a head-mounted iPhone holder is the obsolete Google Cardboard, released in 2014. It provided a cardboard viewer into which you could slot an iPhone or Android smartphone for VR on the cheap. I even have one, but it lacks a head strap and has built-in lenses for 3D images. Google Cardboard was succeeded by Google Daydream, which does have a head strap but seems similarly obsolete. But both were focused on VR rather than vision enhancement.

However, since Google published instructions and templates for making your own Google Cardboard and many other sites released their own versions, it should be possible to create an iPhone-based vision enhancement system, complete with a head strap. I leave that as an exercise to the reader and will award bonus points to anyone who does it and posts a picture. I’m particularly taken with the person who repurposed his iPhone’s box.

How to Identify and Eliminate Abusive Web Notifications

Has a notification appeared on your Mac that claims your McAfee anti-virus software subscription has ended, “Your iCloud is being hacked,” or someone is trying to access your bank account? These attempts to phish you by notification are malware, plain and simple—the form known as adware. The alerts try to trick users into visiting a fake website and entering login credentials or credit card information to facilitate identity theft, just like a phishing attempt via email. Attempting to eliminate the notifications by running anti-malware apps like Malwarebytes, DetectX Swift, or VirusBarrier won’t work. What’s going on?

Randy Singer, who runs the MacAttorney User Group and publishes a variety of pages with helpful Mac advice, passed on this warning about abusive notifications recently. Such abuses of Web push notifications have existed for years, but I’ve never seen one on my Mac. Between Randy’s warning and reader David Roessler writing in a few days later to suggest a similar article, I decided it was time to address the topic.

Unlike regular malware, notification adware doesn’t require an infection, so anti-malware software has nothing to find or remove. Instead, notification adware exploits the capability of Web browsers to let websites display system-level notifications just like native apps. No one would intentionally sign up for adware notifications, of course, but websites can—and increasingly do—ask users if they’d like to receive notifications. There’s nothing inherently wrong with a website offering notifications. As one of many examples, the Discourse software we use for TidBITS Talk offers notifications for those who want to be notified of new messages or replies. But like many well-intentioned technologies, Web notifications can be turned to the dark side.

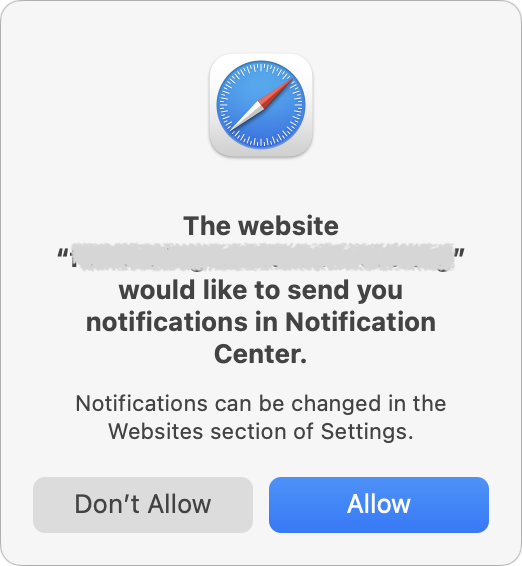

Part of the problem is that agreeing to receive notifications requires nothing more than pressing Return to accept the Allow option when Safari’s permission dialog appears, and websites can present their own dialogs before triggering Safari’s dialog to lull users into complacency. Once notifications have been allowed, they have the imprimatur of coming from macOS, which makes them seem all the more believable.

Of course, if you’re paying attention and are sufficiently technically aware—as most TidBITS readers are—simply click Don’t Allow when a website asks for notification permission. That’s what I do in nearly all instances. I’ve allowed sites to present notifications in only a handful of cases.

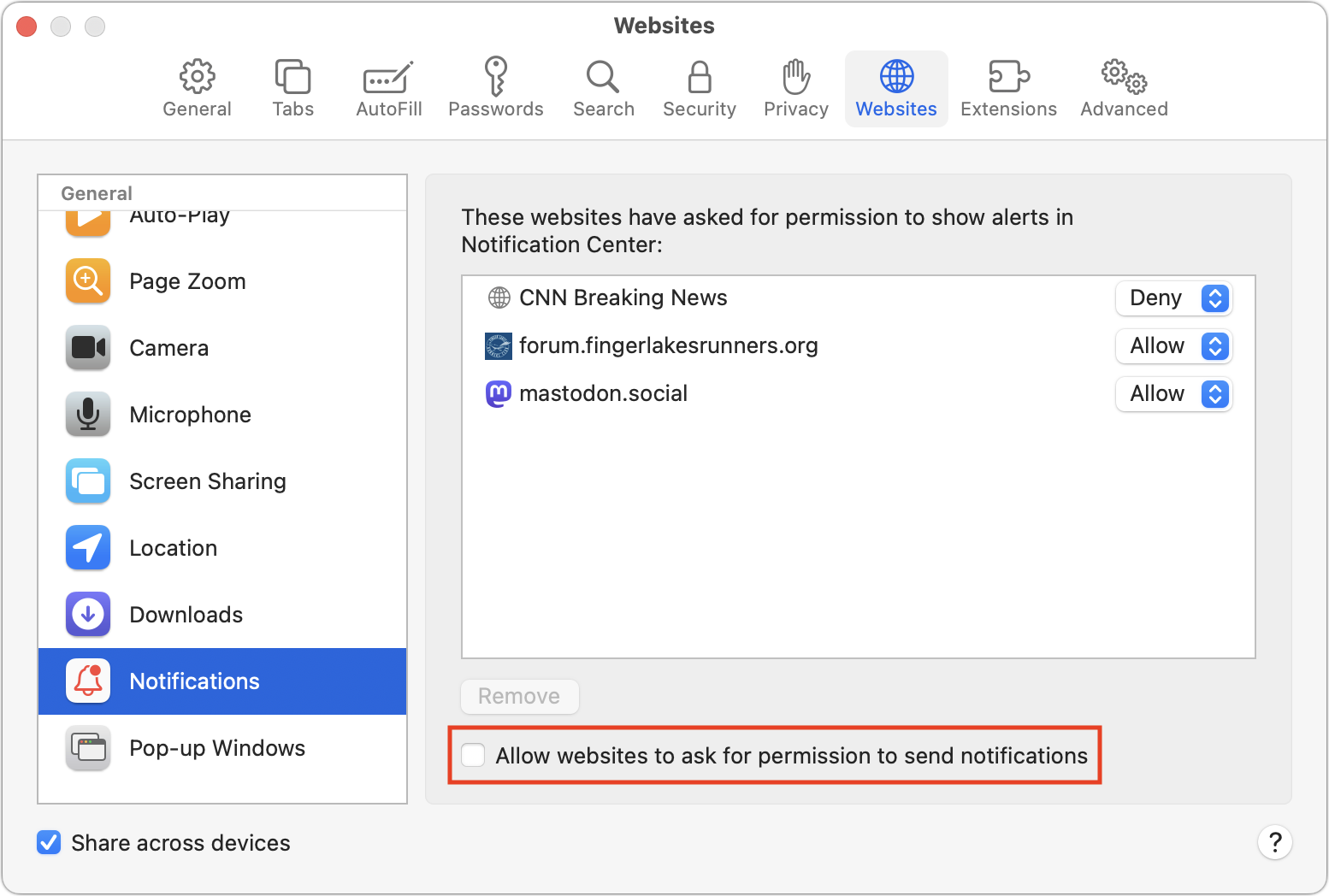

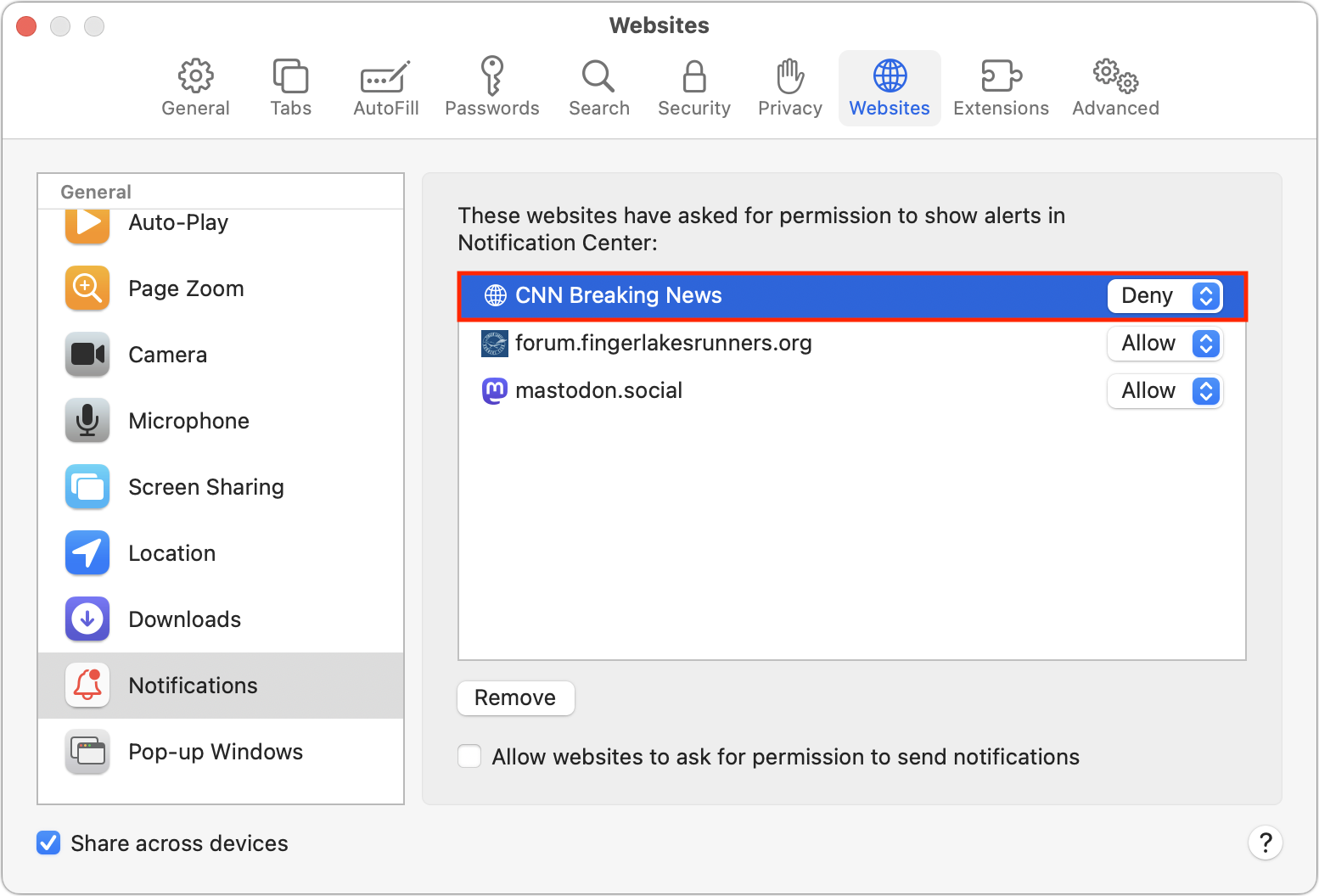

If you’re categorically opposed to notifications or are assisting someone who may not understand what they’re agreeing to, Safari provides a simple way to ensure you’re never asked to allow notifications. Go to Safari > Settings > Websites > Notifications, and deselect “Allow websites to ask for permission to send notifications” at the bottom.

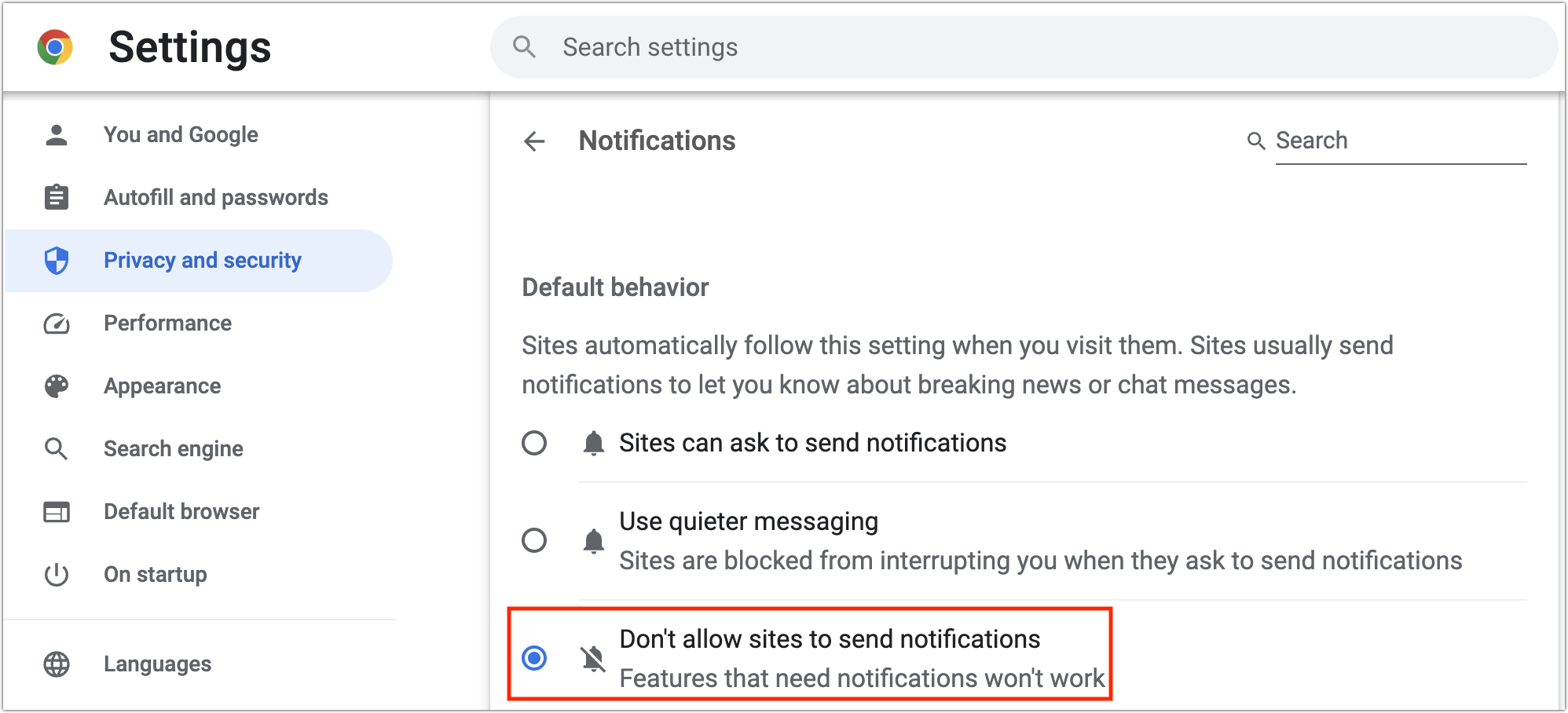

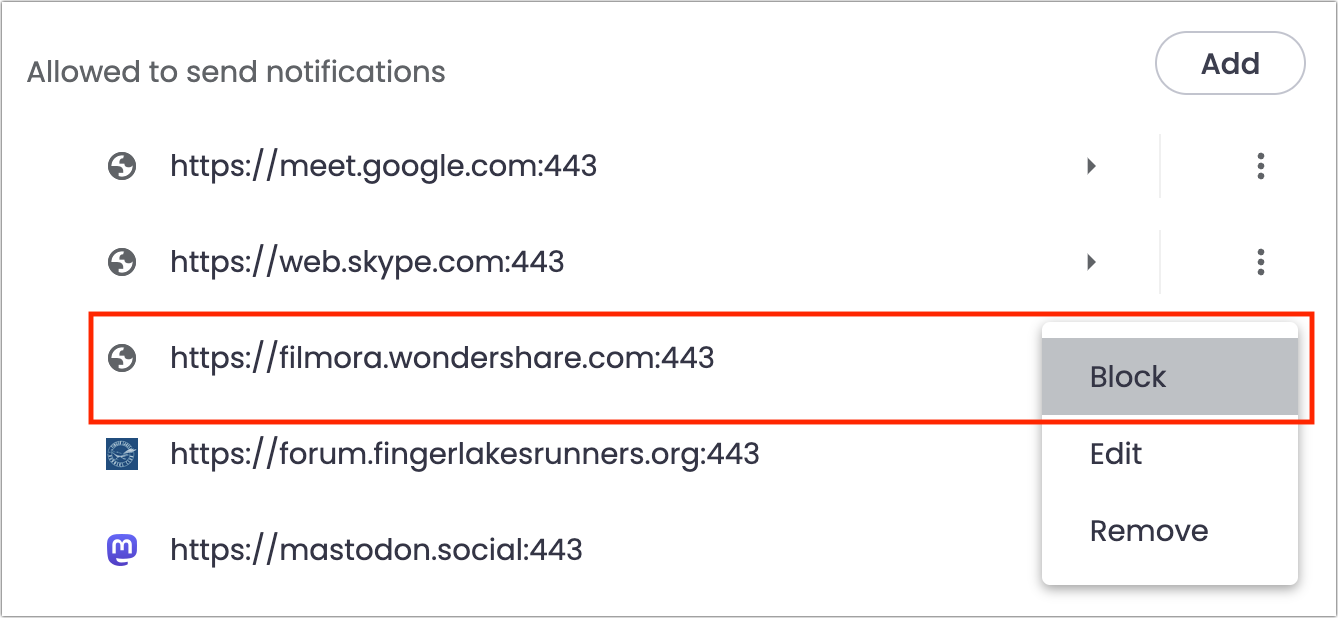

Other Web browsers can also be subverted to show abusive notifications, and they too let you avoid being prompted at all. The interfaces vary slightly, but most will look like Google Chrome, as shown below.

- Arc: Choose Arc > Settings > General > Notifications and select “Don’t allow sites to send notifications.”

- Brave: Navigate to Brave > Settings > Privacy and Security > Site and Shield Settings > Notifications and select “Don’t allow sites to send notifications.”

- Firefox: Go to Firefox > Settings > Privacy & Security > Notifications and select “Block new requests asking to allow notifications.”

- Google Chrome: Navigate to Chrome > Settings > Privacy and Security > Site Settings > Notifications and select “Don’t allow sites to send notifications.”

- Microsoft Edge: Choose Microsoft Edge > Settings > Cookies and Site Permissions > Notifications and turn off “Ask before sending.”

In theory, Chrome should be less susceptible to phishing notifications than Safari, potentially along with other Chrome-derived browsers (everything in the list except Firefox). In 2020, Google introduced the middle option above for “quieter messaging,” which replaces the permission dialog with a bell icon next to the site name in the address bar—click it to allow notifications. In subsequent updates in 2020, Google started identifying websites that display abusive notifications and calling them out in the permission request. I say “in theory” because Apple consultant Adam Rice told me he mostly sees spammy notifications in Chrome.

Disabling “Allow websites to ask for permission to send notifications” prevents new sites from spamming you with notifications. But what about sites that already have permission? It’s easy to block their notifications in Safari too. If you have any sites with Allow in the pop-up menu to the right of their name in the Notifications screen, just choose Deny from that menu. Firefox’s interface is similar. Don’t remove the site because—depending on other settings—that may allow it to ask again for permission.

Chrome-based browsers separate the blocked and allowed sites. To block a website whose notifications you no longer want to receive, click the button to the right and choose Block.

Finally, if these notifications plague you or someone you know, consider the websites being visited. Websites that trick users into allowing notifications so they can display phishing notifications are malicious, or at least complicit in allowing their visitors to be targeted by including third-party elements that engage in this phishing. Ideally, you’d avoid them.

It may not be that easy. In 2020, security journalist Brian Krebs wrote about a service called PushWelcome that advertised the ability for website publishers to monetize their traffic. It asked publishers to include a small script that generated the often-deceptive notification requests on legitimate sites. PushWelcome appears defunct now, but other such ad networks may still exist.

I realized it’s easier to say, “Don’t visit sketchy websites,” than explain what makes a site problematic. Nevertheless, if you—or the person you’re helping—have any doubt about the legitimacy of a website or the website owner’s security capabilities (for protecting their site against subversion by hackers or being deceived by an ad network like PushWelcome), you might not want to trust it to display notifications or collect any personal information.

If you run across a site that pushes spammy notifications at you, report it to Google Safe Browsing, which warns users about problematic sites. It currently issues over 3 million warnings per week, which sounds like a lot until you see it offered over 50 million warnings per week in mid-2016.

To stay safe on the Web, browse with care and click with intention.