#1699: Easy steps for clearing space on your Mac, cartoonists and technology, Walmart selling M1 MacBook Air, floppy disks forever, what’s your favorite podcast app?

We have two feature articles for you this week. Glenn Fleishman leads off with a look at how today’s newspaper cartoonists rely on digital tools, but not in the way most of us would expect. Then Adam Engst goes deep with 21 carefully considered and explained steps for clearing space on your Mac, starting with the easiest, safest, and most effective. We also briefly cover how Walmart has started selling the M1 MacBook Air and share an interview with the last man standing in the floppy disk business. Finally, this week’s Do You Use It? poll asks about your preferred podcast app. Notable Mac app releases this week include Audio Hijack 4.3.2, GarageBand 10.4.11, Little Snitch 5.7.4, Microsoft Office for Mac 16.83, Parallels Desktop 19.3, and Piezo 1.9.

Newspaper Cartoonists Rely on Digital Tools, but Not as You’d Expect

I spent dozens of hours last fall interviewing newspaper cartoonists about how they draw their work, assuming that many would have adopted modern tools like a Wacom Cintiq tablet or at least a digital stylus paired with something like an iPad. Instead, I was surprised to find that many rely on traditional media, like ink, paint, and watercolor. Even more surprising? Many younger artists, who had the choice of whether to start in analog or digital, work on paper instead of on screen.

I expected that most artists producing daily cartoons would have made a partial or total conversion to drawing and producing their work digitally, thanks to the advantages in time and effort. Perhaps those who started working before the 1990s would largely stick to traditional media, but I reckoned even some percentage of them would have shifted over. But no. While they don’t draw digitally, they’re happy to leverage digital technologies in other ways.

The persistent use of liquid stuff on paper is partly because modern reproduction technology makes it just as easy to work in older media as with digital tools. The ease of scanning, or even taking high-resolution flat photos of analog work, outweighs the seeming advantages of an all-digital workflow for those who prefer the messy, unpredictable, and sometimes frustrating limitations of materials for the physical feedback, happy accidents, and familiarity they provide.

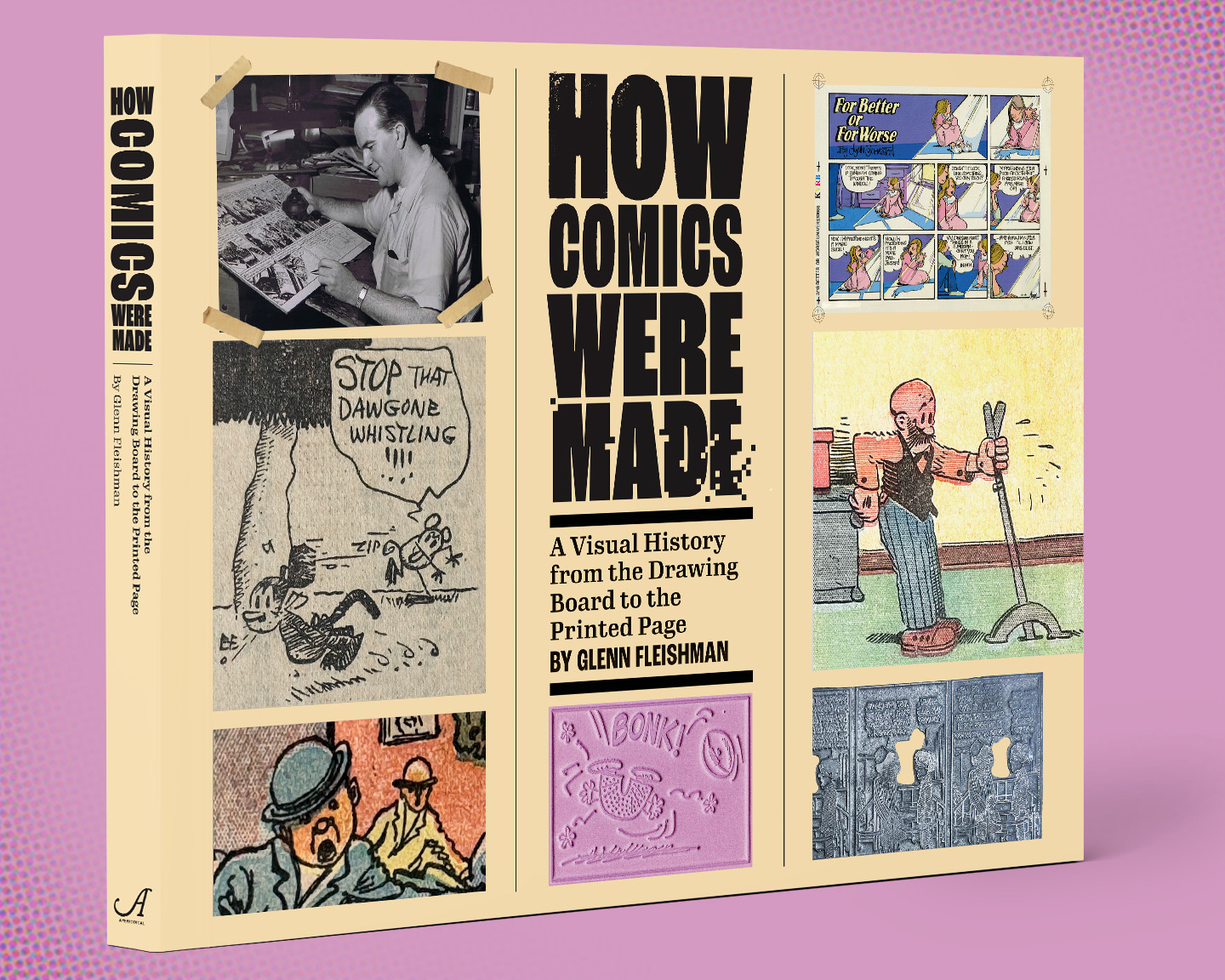

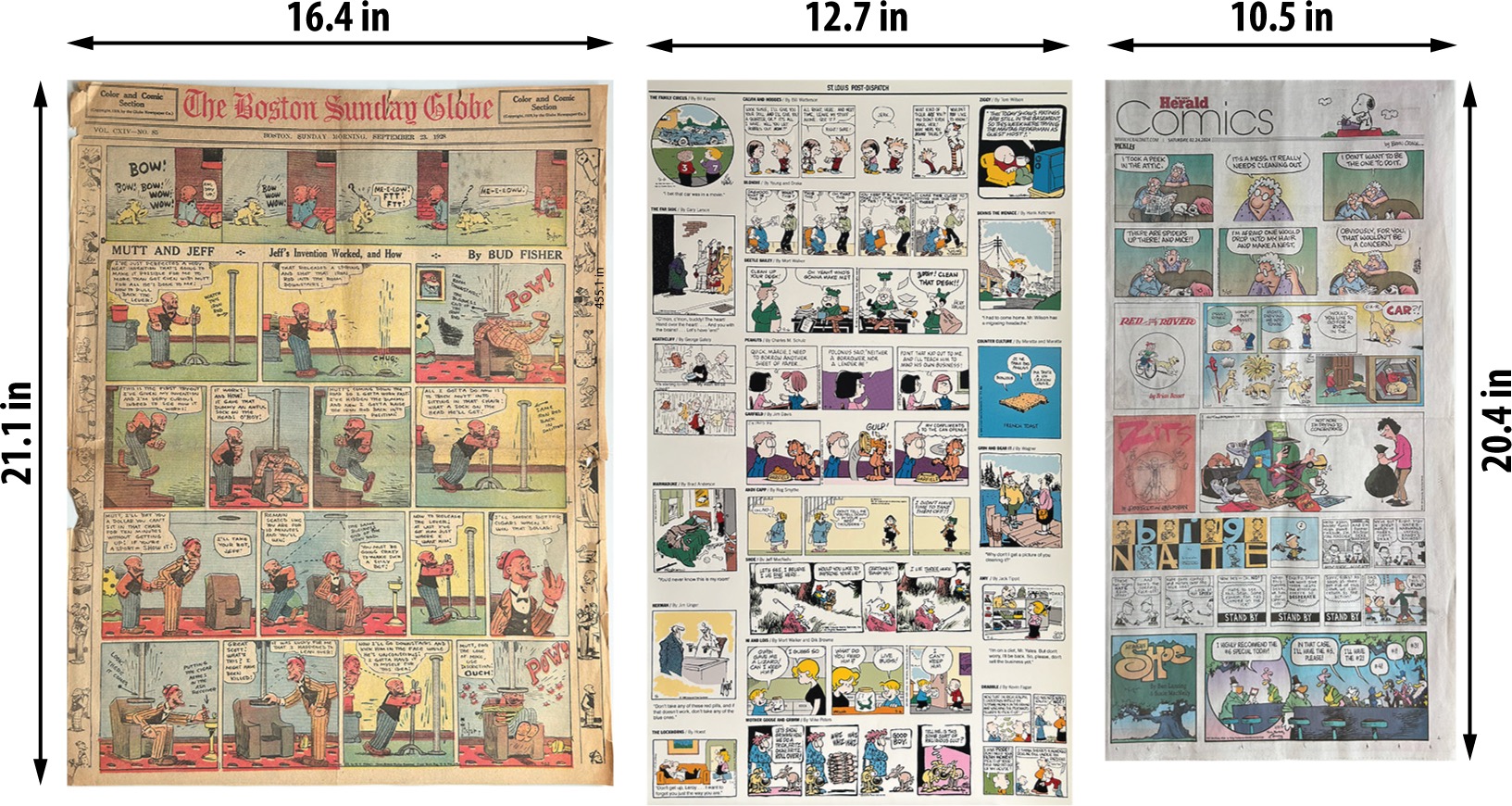

These interviews were part of my multi-year research for a book, How Comics Were Made: A Visual History from the Drawing Board to the Printed Page, that I’m currently crowdfunding with an anticipated ship date late in 2024. My book starts in the 1890s and follows North American newspaper comic production and reproduction to the modern days, focusing on how artists drew their strips and worked their way through the transformations necessary to get artwork onto a newsprint page or digital display.

Help Me, I’m Shrinking!

Because of the contraction in both newspaper circulation and the size (dimensions and page counts) of print newspapers, cartoonists have a harder time reaching a mass audience through a single-point source—the comics syndicate, which used to be the apex of an artist’s career in sequential storytelling outside of comic books. Newspapers still pay a pretty penny to syndicates for comics, but fees are based on reach. With fewer newspapers reaching fewer people in print, syndicate fees have dropped. Plus, as the newspaper business contracts, newspapers are cutting costs everywhere they can, resulting in smaller print formats and thus smaller rectangles in which cartoonists tell their stories. (Online audiences may be huge, but most newspapers’ paywall revenue is modest compared to print, and a tiny amount of that is remitted to syndicates for online cartoon reading.)

From the 1910s to the 1960s, cartoonists like Bud Fisher (“Mutt and Jeff”) and Robert Ripley (“Ripley’s Believe It or Not”) lived like kings. Newspaper pages back then were often 50% larger, and a single Sunday comic could fill the sheet. A reasonable number of those artists made the equivalent in today’s money of over one million dollars a year from syndication fees—and much more when merchandise, plays and musicals, and other adaptations were figured in. Fisher’s annual income of $250,000, revealed in a divorce proceeding, would be $4.5 million today! (The judge remarked, “I do not see how anybody can pay money for that nonsense.”) Ripley made even more and had his own private island. Even a cartoonist with a modest circulation of newspapers could have had a middle-class living.

The shrinkage means that today’s cartoonists work as much as they always did for less money. Famous artists of yesteryear like George McManus (“Bringing Up Father”) and Al Capp (the ill-spirited “Li’l Abner” artist) might have had several people handling business, inking their penciled strips, and creating coloring guides for syndicated Sunday comics. Shortly after starting out in 1979, Lynn Johnston (“For Better or For Worse”) had someone who drew in backgrounds and another who handled color so she could focus on writing, penciling, and primary inking, she told me in an interview. But that didn’t last, and today, all but the giants—like Jim Davis (“Garfield”)—are lucky if they can afford to hire any help.

Given that environment, I thought today’s cartoonists would be obliged to go digital—they simply wouldn’t have time for anything else. And with smaller reproduction sizes, the detail they might have sought in drawing by hand on paper might mean less, too. (You can, of course, put infinite detail in when drawing digitally, but it can also be a shortcut to simplicity.) However, many cartoonists remain resolutely conventional while leveraging the best of the available digital options—whether correction, coloring, lettering with a font, or other manipulations.

Cartoonists can bring digital tools to bear in specific ways because they can scan their work and translate it into digital form. While we take scanning for granted, it was transformative for cartooning because it allowed artists to work directly in color for the first time after nearly a century of working indirectly.

One Drawing, Many Outcomes

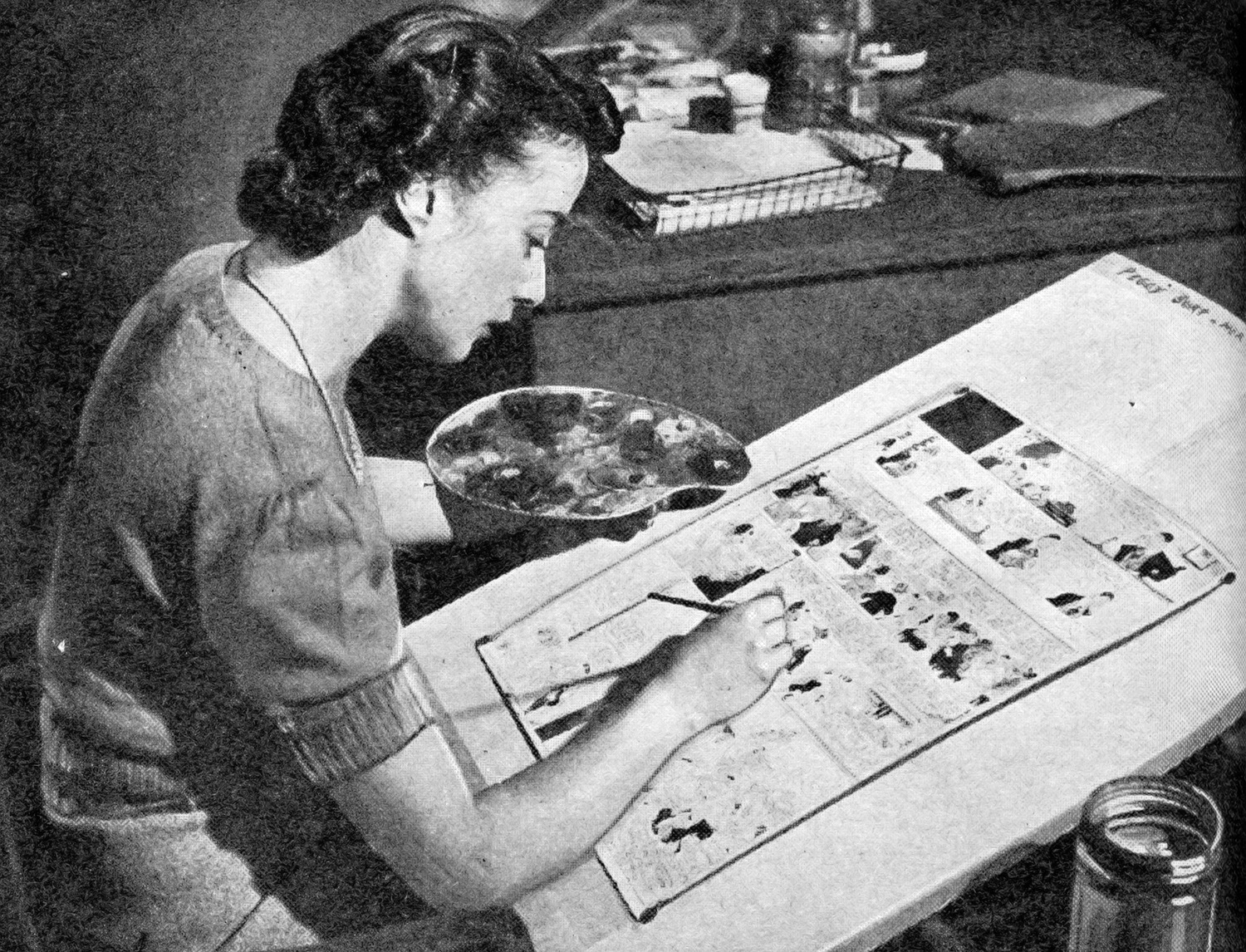

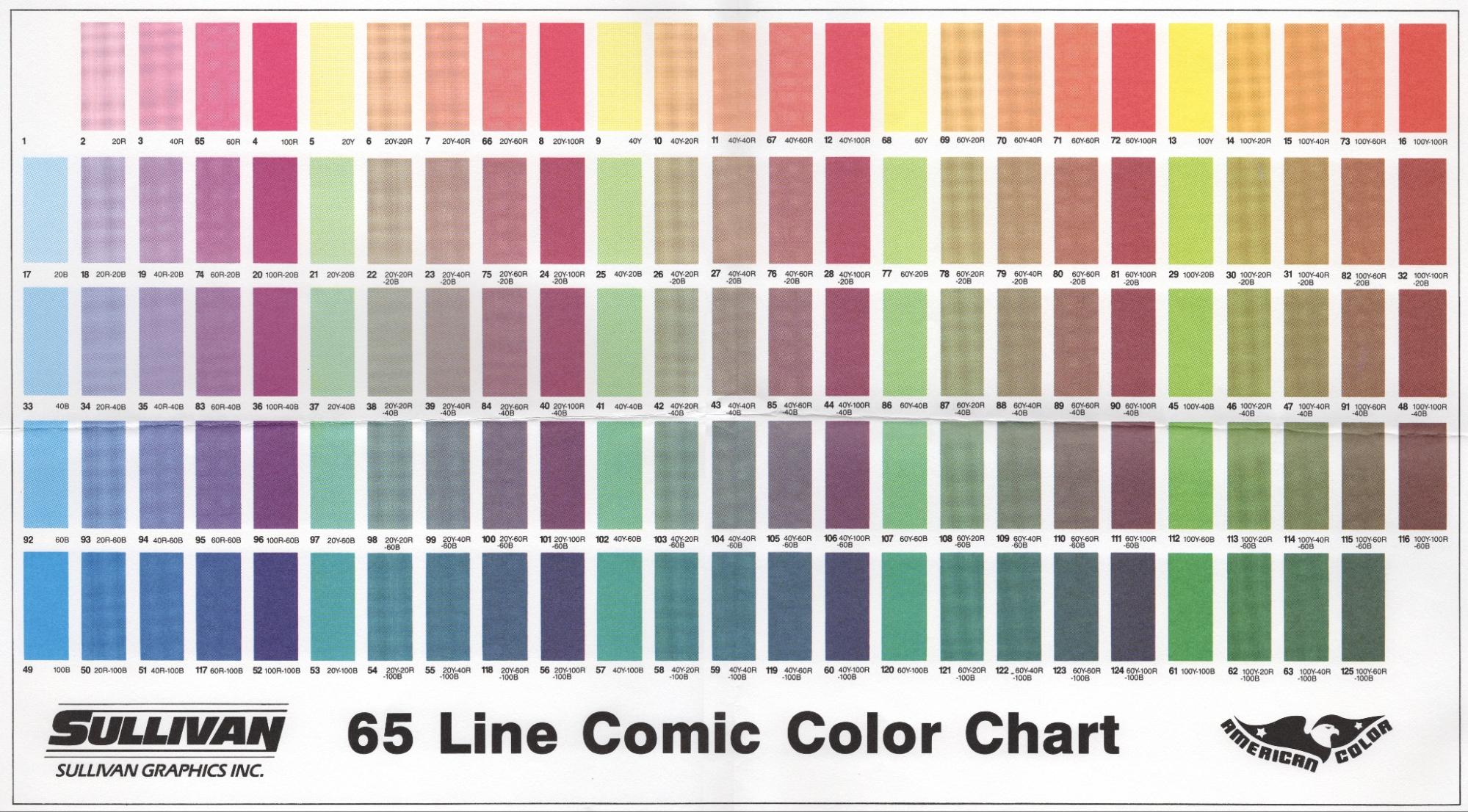

Before scanning was an option, in the pre-digital days, cartoonists worked entirely in black ink or paints: no grays, no solid colors, no color tints. A cartoonist or a colorist would take a copy of a daily strip or a Sunday color and mark it for gray tints for weekdays and the myriad colors required for the color funnies. Colorists might rely on colored pencils, watercolors, markers, or other materials to indicate colors, but they used a chart provided by the syndicate’s engraving partner or printer to match those colors with numbers, which were written over or pointing to the colored elements.

The comic’s color guide was, in essence, a “paint by numbers” reference for newspapers. Cartoonists advised the syndicate on coloring, and then the syndicates sent out molds or other separated color pieces, and newspapers put them on paper.

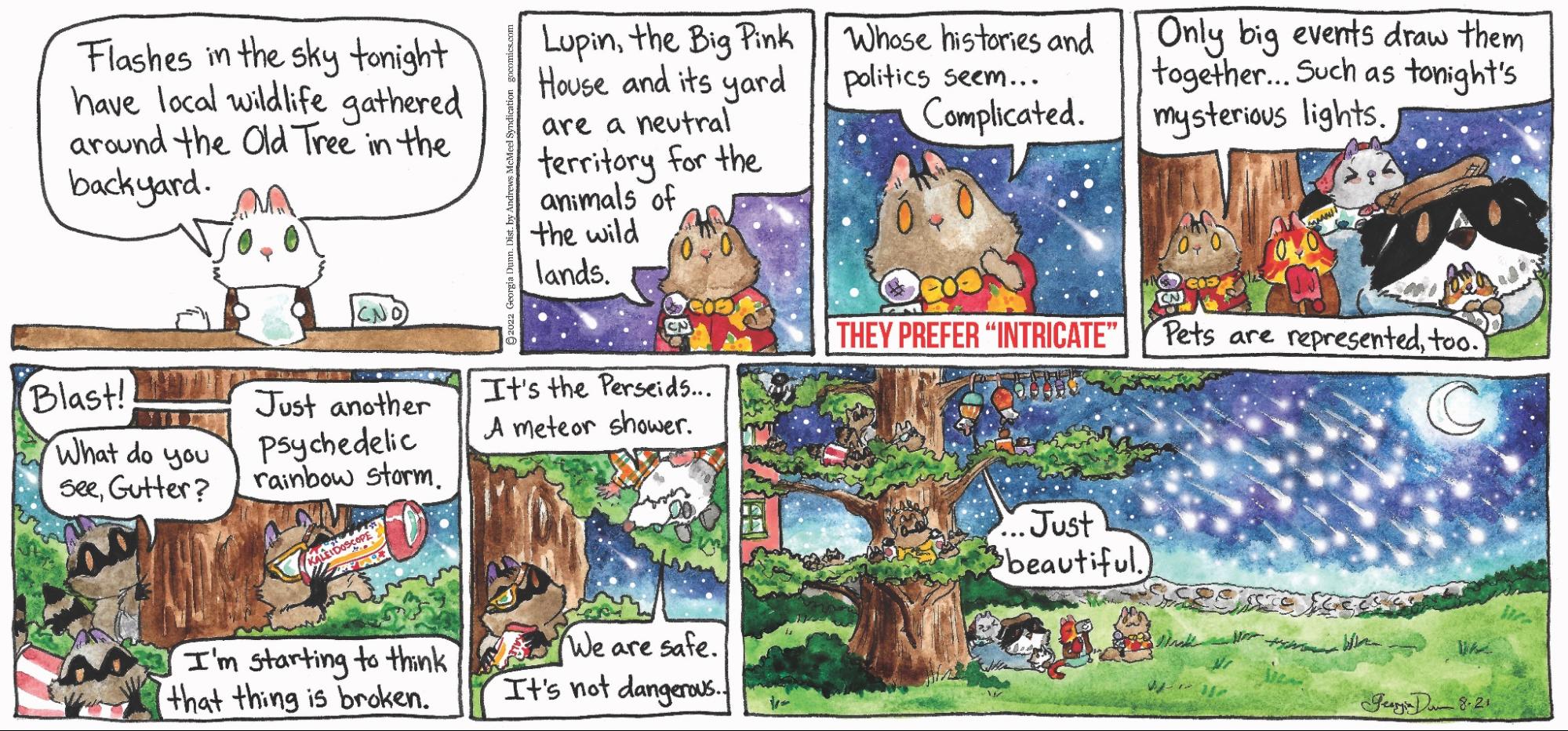

However, once scanning became an option, any media could be the starting or finishing point for a comic. I recently conducted a lengthy video interview with Georgia Dunn (“Breaking Cat News”), whose strip has been in print and online syndication for a decade. She began her artistic career working in watercolor but also became proficient in Photoshop while helping her father with photo restoration.

She tried to make “Breaking Cat News” digitally but found it broke her drawing style and fluency. Using digital tools turned out to be inefficient and even maddening. By penciling and using watercolors, she was writing and developing her storylines through her hands, often coming up with the next week’s installment as she drew the current one, though she was unaware of that until she tried to change. She also found lettering by hand on paper provided another chance to review her dialog and was more flexible than prepping spaces into which she would have to drop a digital version of her lettering.

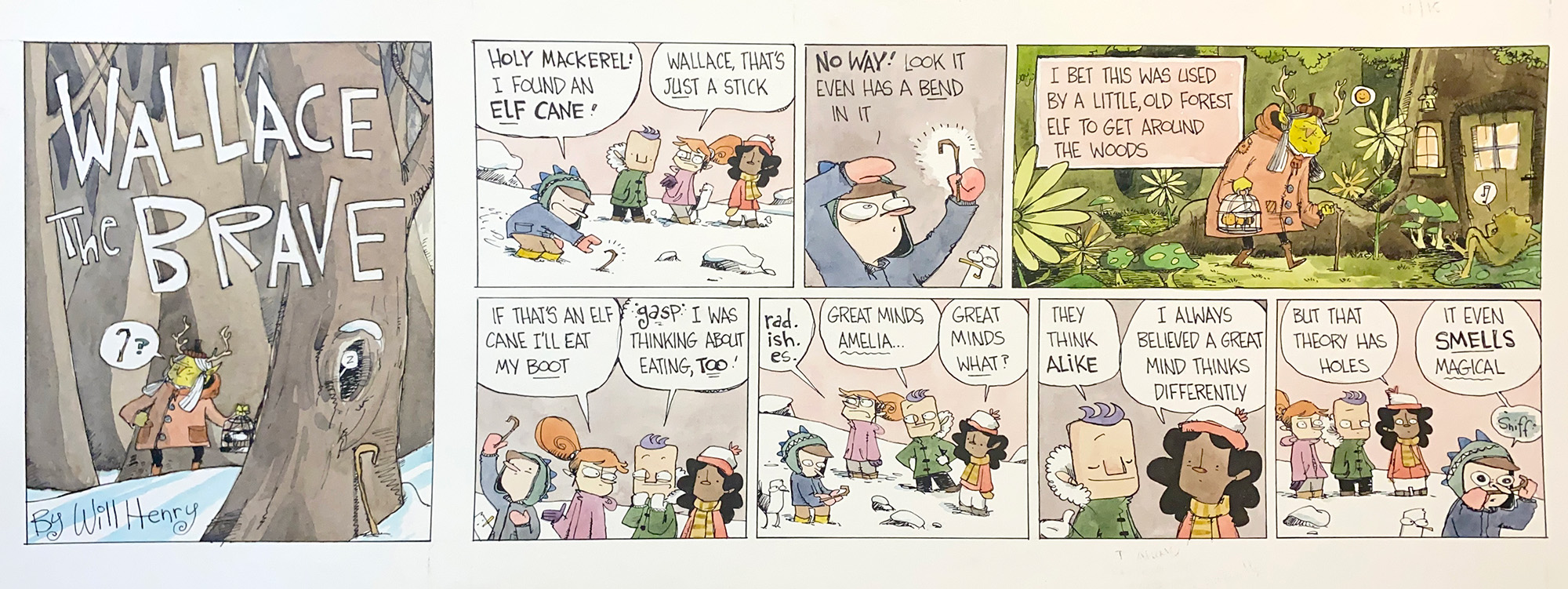

Will Henry, creator of “Wallace the Brave,” also works in watercolors. He described his enjoyment of the process to me:

I take pride in the mistakes in this comic, because when working with a pen and nib, you really get one chance—you can’t wipe some stuff out. If I worked digitally with my personality, I would be doing the line over and over and over again. Absolutely perfect. But one of the things that I think the tools I use and the product I create or the comic I create—I think there’s an overall acceptance of the non-perfect, the imperfect.

When you’re working with the pen and the nib, maybe the pen will grab a little paper and you’ll have a thicker line than you wanted. Or maybe it’s a colder day and the ink is a little thicker, or gravity will pull the ink down to an area you didn’t want. But it works, and things happen that you don’t expect. And it wouldn’t have happened if I wasn’t using the medium.

However, neither Georgia nor Will nor any of the many other cartoonists I spoke to who work in traditional media stops there. For instance, Georgia edits after scanning to clean up errors, correct colors, and drop in some elements digitally (like items designed to look typeset), all before previewing her work and sending it off to the syndicate.

Many cartoonists work in a hybrid of old and new: they draw in black ink, scan, and then digitally apply color and lettering. John “Derf” Backderf, who started as a cartoonist in the 1990s and pursued a career through alt-weekly syndication and graphic novels (like My Friend Dahmer and Kent State), said he pencils everything, drawing and letters. But he prefers to use the penciled letters only for placement and sizing—he doesn’t ink them. When he scans his inked drawings, he erases the penciled areas and replaces them with a font created from his lettering.

Most daily cartoons are delivered in both black-and-white and color because some newspapers print their daily and Sunday comics in color; Sunday comics are nearly universally in color.

Digitally sophisticated cartoonists will convert the file into CMYK—the four process colors of cyan, magenta, yellow, and black used for newspaper and most other offset color printing—so they can preview how their color will appear in print. Many, however, rely on the syndicates to handle that conversion and provide feedback when something doesn’t look right.

Even though newspapers still handle the printing, turning a comic into a digital format provides much more end-to-end consistency when it comes out on paper.

Cartoonists Face a Forked Future

The future of newspapers is highly uncertain. Daily newspaper circulation in the United States hovered at around 30% of the US population (units per person) between 1940 and 1973, peaking at around 63 million in 1973. That meant nearly every household received a paper, as did many businesses and libraries, schools, and other institutions. A slow decline followed, picking up steam and accelerating in the 2000s. Now, only an estimated 21 million papers go out every Monday to Friday, less than 6% of the US population and fewer than a fifth of households.

The ongoing drop in newspaper dimensions, page count, and circulation threatens the future of the newspaper comics format, which debuted in the late 1800s and was perfected a few years into the new century. The number of different strips running has plunged, too. Recently, the Gannett newspaper chain took the choice of comics away from local or regional editors, allowing them to pick sets from among 34 strips, which include several popular ones in re-runs with a deceased or retired creator, like “Peanuts” and “For Better or For Worse.” (Only one woman remains in this group: “For Better or For Worse” creator Lynn Johnston, who is universally beloved among other cartoonists but not producing new work.) Gannett’s limited choice of comics has been a boon for some well-known cartoonists and estates, but others I’ve spoken to have lost a quarter or a third of their syndication revenue as a result.

While webcomics are a viable outlet for distribution, supporting both comic-book style and newspaper-style strips along with many unclassifiable efforts, the online medium doesn’t always provide the revenue cartoonists need to make or supplement a living wage. Cartoonists who found themselves on firm footing for years or decades have had to consider how to reinvent themselves. For instance, Jim Keefe, a long-time colorist at King Features who became the artist behind “Flash Gordon” and “Sally Forth,” launched a Patreon to discuss his history in comics, talk about techniques, and post drawings, videos, and artwork. (Jim also has an amazing blog for anyone interested in comics and syndication history.)

Artists who started in webcomics may have a leg up as the field faces a need for new readers, new markets, and new revenue. Modern cartoonists already know that a good portion of their readership is looking at their work on a screen, but even then, rarely at the same size or in the same format. Even the sequential horizontal organization of standard wide or multi-panel daily strips may be reformatted into vertical panel sequences on some displays or websites. Then you have to figure in later reproductions in print and ebook collections. Daily cartoonists might be read on a newspaper’s website, on a syndicate’s site, and on the cartoonist’s site or Patreon campaign, as well as on social media, just on the first day or so of release.

Today’s most agile cartoonists have made multi-destination publishing a major thrust of their efforts. Lex Fajardo, creator of the page-based “Kid Beowulf” young-adult webcomic, first posts on his own site, after which the comics appear at GoComics and are then collected in books. (Lex’s day job is editorial director of the Charles M. Schulz Creative Associates, where he oversees similar processes with “Peanuts” reruns.)

The best news I have about comics is that there are multiple paths forward. Once, syndication was the only way to become a success, which forced cartoonists to use a limited set of traditional media and master technical issues required by syndicates and newspapers. Now, cartoonists can use any media they want, old or new, difficult or easy, analog or digital, and transform their work in myriad ways for publishing in many different channels.

No one suspects a new golden age is around the corner—the number of cartoonists who could make even $100,000 or more per year from their daily work is dwindling to the fingers of a few hands. But where there is art and where there are readers, new comics will bloom. I hope this rich mix of old media and new technology becomes part of the catalyst.

If you found this article interesting, consider supporting Glenn Fleishman’s Kickstarter campaign for How Comics Were Made: A Visual History from the Drawing Board to the Printed Page.

Follow These Steps to Clear Space on Your Mac

It’s inevitable that many of us will run low on free disk space on our Macs. The worst-case scenario is that you’ll run out entirely, which will cause your apps to exhibit all sorts of undesirable behavior or even render your Mac unusable! Don’t let it get to that point. The rule of thumb is that you want to keep at least 10% to 20% of your startup drive free to give macOS and everyday activities some breathing room. It’s necessary to keep that much space free for various reasons, including:

- Many apps rely on caches and temporary files that may require non-trivial amounts of space.

- If apps use up your Mac’s physical memory, macOS falls back on virtual memory, which creates large swap files.

- Time Machine creates snapshots on the internal drive before transferring them to a destination volume.

- Installing an upgrade to macOS requires significant amounts of free space.

What’s the very worst that can happen? Contributing editor Glenn Fleishman recently had to wipe one of his teenagers’ Macs after a massive Steam game download led to stalled Time Machine snapshots, resulting in a Mac with just 41K free. They tried numerous approaches to clearing space, but nothing worked—every attempt to delete files was met with errors complaining about the lack of free space. The Mac couldn’t even restart except into macOS Recovery. Fortunately, they had a Time Machine backup, and although full restores failed for unrelated reasons, its files were available for manual restoration.

Manually clearing space isn’t worth the effort if you have hundreds of gigabytes free. For instance, on a 1 TB drive, there is no benefit in having 500 GB free instead of 400 GB. Be more concerned if that drive has only 120 GB free.

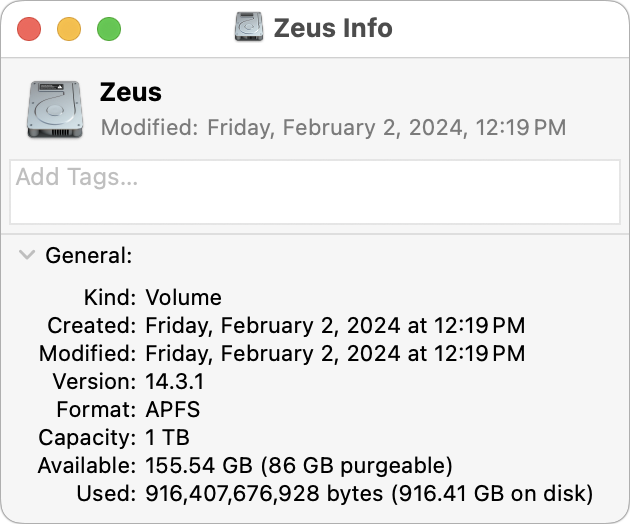

Longtime Mac users often get caught up in looking at the amount of free space reported by the Finder. We’ll check the storage numbers shown in a Get Info dialog, delete something, and check again. Don’t waste your time! Space management on the Mac is now largely indeterminate thanks to APFS, Time Machine snapshots, purgeable space, and more, as Howard Oakley explains. These technologies render the Finder-reported number unreliable at any given point in time. Even after you empty the Trash, it may take macOS several hours or more to update its free space reports. Restarting may or may not help trigger a recalculation.

Longtime Mac users often get caught up in looking at the amount of free space reported by the Finder. We’ll check the storage numbers shown in a Get Info dialog, delete something, and check again. Don’t waste your time! Space management on the Mac is now largely indeterminate thanks to APFS, Time Machine snapshots, purgeable space, and more, as Howard Oakley explains. These technologies render the Finder-reported number unreliable at any given point in time. Even after you empty the Trash, it may take macOS several hours or more to update its free space reports. Restarting may or may not help trigger a recalculation.

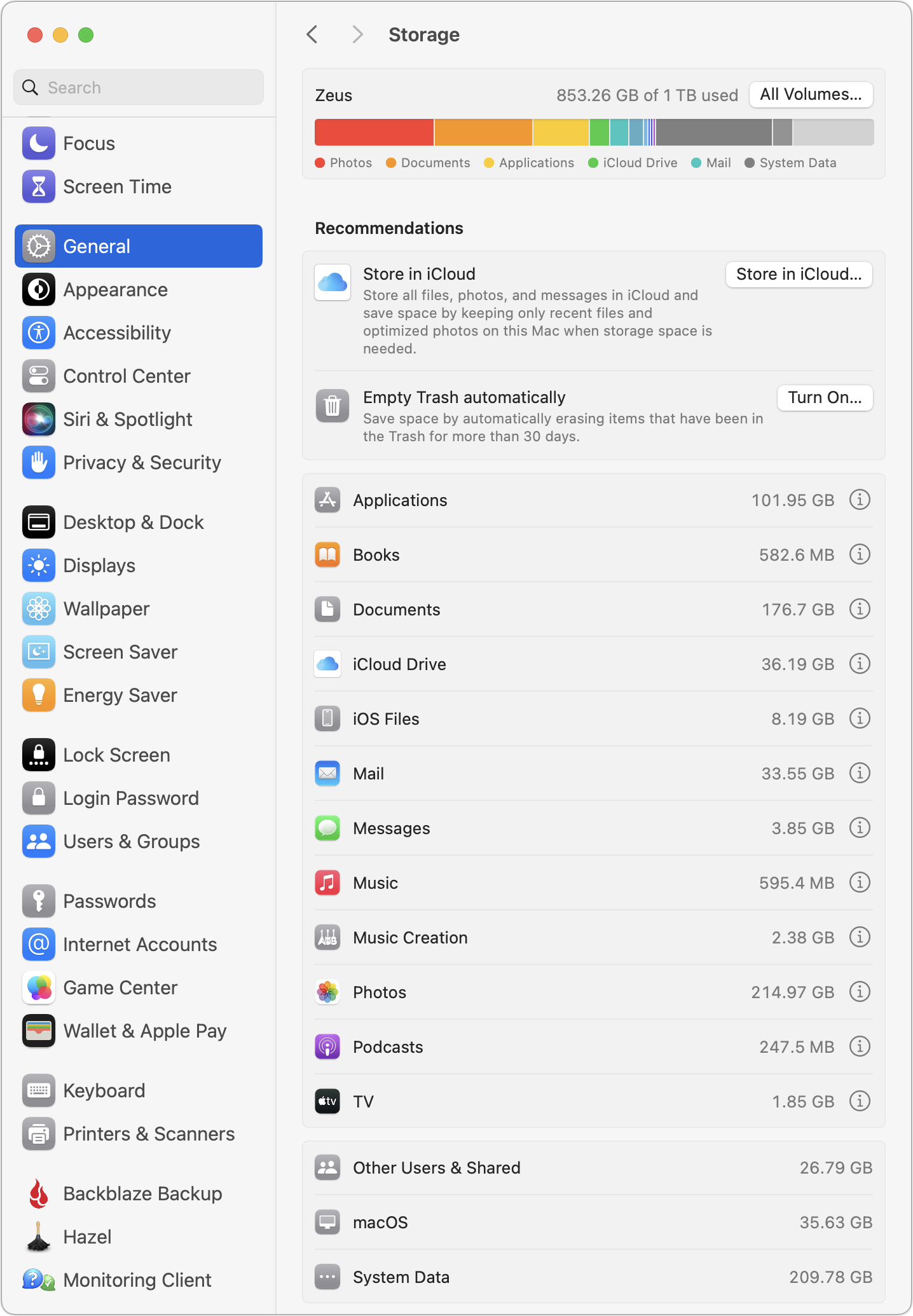

Instead of stressing about exact numbers, I want to offer you a set of steps that will clear space quickly and easily on most Macs. Apple has advice here, and it’s not wrong, but it’s far from comprehensive. macOS also provides tools to help reduce unneeded drive usage at System Settings > General > Storage. Some are worthwhile; others do little or are incomplete. I’ll cover the helpful ones below.

I’ve arranged these steps in a particular order: I start with the easiest to perform, the most likely to help, and the least likely to lead you to delete something important. Later steps become more complicated and are more likely to require some thought to avoid erasing important data. Two points to pay attention to:

- Don’t follow the steps mindlessly, particularly as you get further down the list! At all times, you should make sure any to-be-deleted data is truly unnecessary. That could be more difficult if you’re helping a friend or relative with their Mac—don’t immediately take their word for it when they say something isn’t necessary.

- Depending on your goal, you don’t need to follow all these steps—think of them as a set of increasingly complicated recommendations instead of a mandatory series. It’s fine to stop once you think you’ve cleared enough space, remembering that the Finder probably won’t update immediately. However, error conditions caused by a lack of free space may disappear before the Finder’s numbers reflect reality.

One final note: I try to use the word “delete” for instances where the data will be gone afterward and the word “remove” when you’re only deleting the local copy of something that can easily be downloaded again from the cloud.

1: Empty the Trash

Choosing Finder > Empty Trash is obvious, I know, but not everyone does it regularly. Because modern Macs have so much storage, it’s easy to forget to empty it for months. If desired, you can set macOS to delete files automatically. Look in Finder > Settings/Preferences > Advanced for the “Remove items from the Trash after 30 days” checkbox.

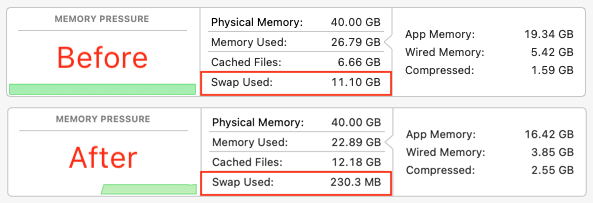

2: Restart, Possibly in Safe Mode

How could a simple restart reclaim disk space? Remember those virtual memory swap files I mentioned? When your Mac goes weeks or more without restarting, swap files consume a lot of space. A restart lets macOS start fresh. While writing this article, when I checked Activity Monitor’s Memory screen, my Mac was using 11 GB of space for swap files. After I restarted, that number dropped to 230 MB and remained there 90 minutes later for the second screenshot. Clearing swap files won’t help permanently, but it can be helpful briefly—particularly when the Finder reports it doesn’t have enough storage to complete file deletions or other activities.

To reclaim more space temporarily, consider restarting in safe mode, which clears potentially large caches. Since the introduction of Macs with Apple silicon, there are now two ways to boot into safe mode:

- On an Intel-based Mac, restart your Mac and immediately press and hold the Shift key until you see the login window.

- On a Mac with Apple silicon, first shut down. Then, press and hold the power button until “Loading startup options” appears. Select a volume, press and hold the Shift key, and click the Continue in Safe Mode button.

To have safe mode delete caches, you just need to get to the Finder. Once the Mac finishes booting in safe mode, you can restart again with no modifiers or startup steps to return to work—you don’t need to carry out any tasks within safe mode. Restarting in safe mode did nothing useful in my testing, but it’s easy and harmless.

Some suggest clearing logs and caches by running Titanium Software’s Maintenance, a subset of the company’s free maintenance utility Onyx. It offers many options for clearing space, but I’m hesitant to recommend it because I don’t know precisely what it does. When I tested Maintenance with a reasonable set of options, I couldn’t tell if it cleared anything at all. Also, Maintenance automatically restarts the Mac once it has reclaimed space, but several apps behaved oddly on the next boot, so I had to restart my iMac again before everything returned to normal.

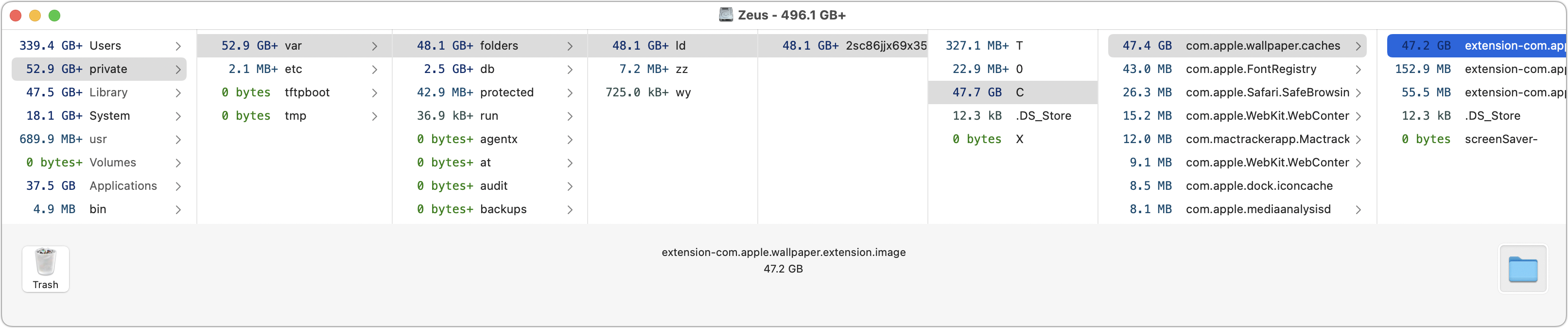

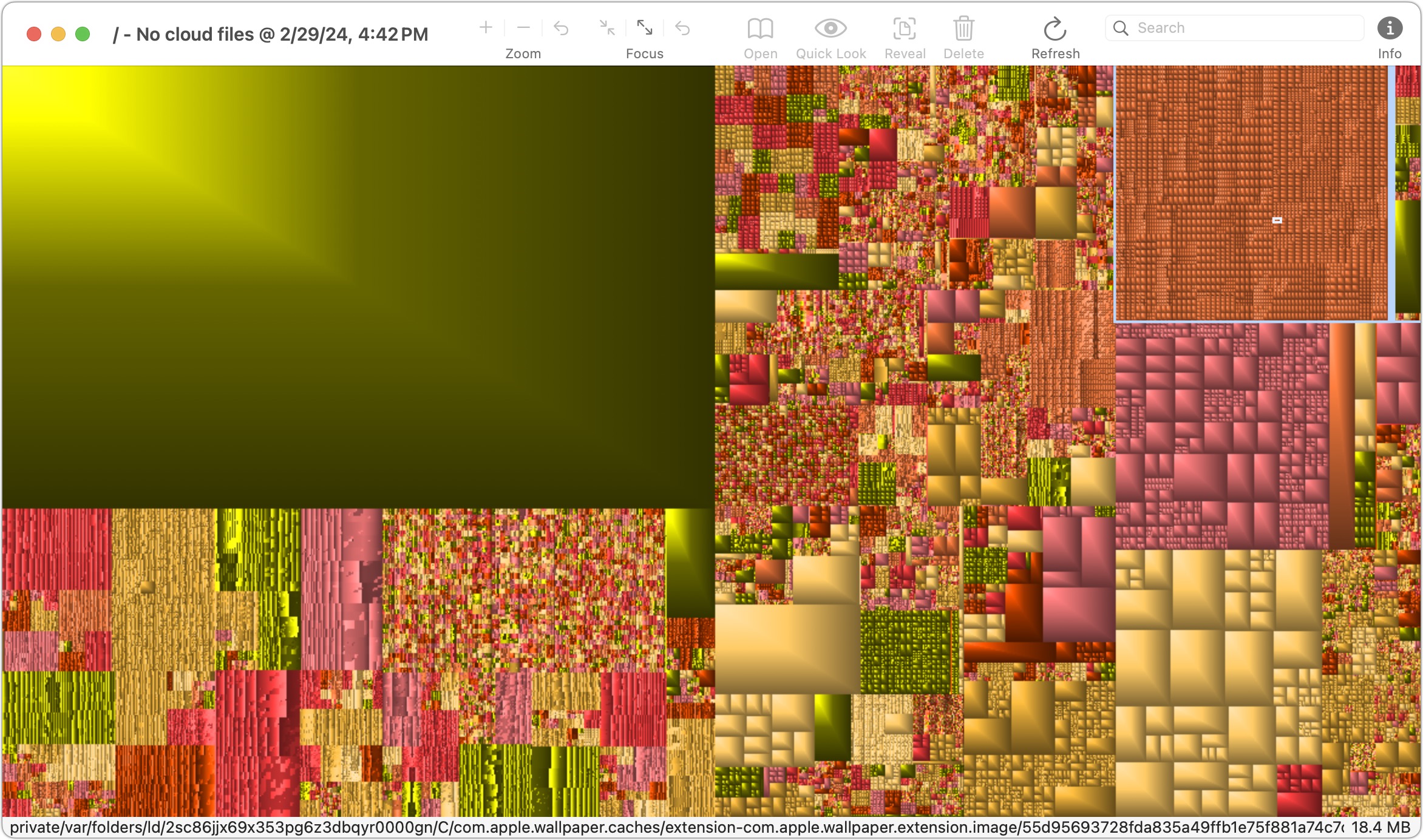

3: Scan for Large Files and Huge Folders

It can be hard to determine what consumes large quantities of your drive space, so I recommend using a utility designed to help identify egregious offenders. These include the free GrandPerspective, OmniDiskSweeper, Disk Inventory X, and the $9.99 DaisyDisk. I like GrandPerspective’s graphical visualization, but it’s much slower to scan than OmniDiskSweeper, which relies on a text-based hierarchical view like the Finder’s Column View. The open-source Disk Inventory X is older. The popular DaisyDisk offers a combination of text and graphical approaches.

These apps scan your entire drive—you’ll have to grant them Full Disk Access permission—and help you identify excessively large files and folders, which can help you decide which of the following steps to focus on first. They’re valuable for finding and deleting out-of-control log files, cache files that aren’t automatically removed, large installers or updates you no longer need, and massive files like unused virtual machines.

The revelations can be staggering. For instance, the OmniDiskSweeper and GrandPerspective windows below show 47 GB of wallpaper cache files. I use Irvue to randomize my desktop wallpaper, and I discovered that it chooses to download multiple copies of the same image rather than caching previously retrieved media. I have to look into that.

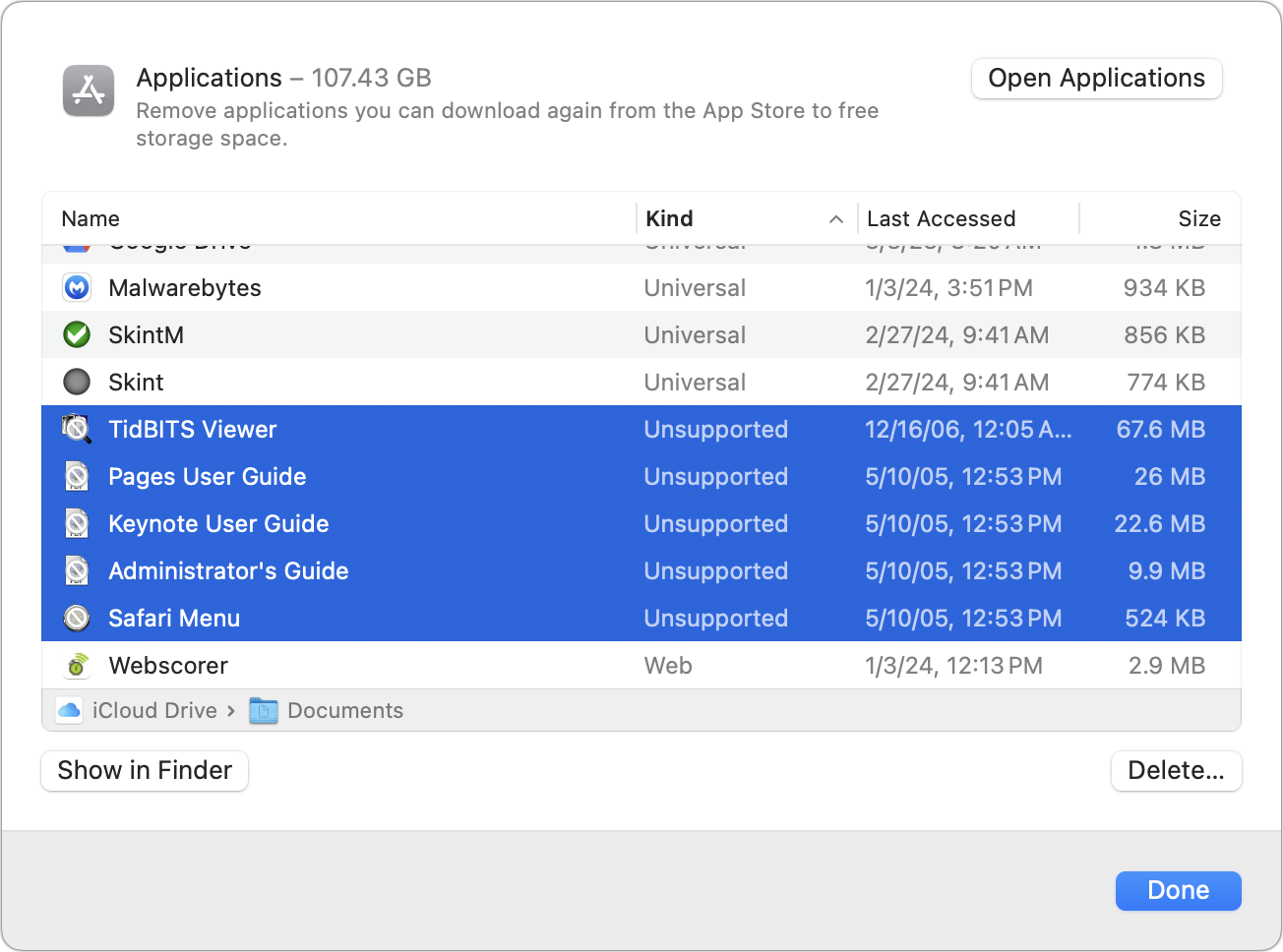

4: Delete 32-bit Apps and Duplicate Apps

On older Macs and those whose contents have been migrated forward across multiple versions of macOS, it’s easy to end up with defunct 32-bit apps that no longer run and may as well be deleted. Open System Settings > General > Storage > Applications, click the Kind column header, select all the apps marked Unsupported, and click Delete. You can do the same with apps marked Duplicate.

More generally, it’s usually safe to delete apps you no longer use since most can be downloaded again from the Mac App Store or a developer’s website should you ever need them. Sorting the Applications list by size may reveal some multi-gigabyte apps you haven’t launched in years.

To be sure you’re clearing out associated media, logs, preferences, launch agents, and other files when you delete an app, it may be worth employing a utility like AppCleaner, CleanMyMac X, or Hazel. When you delete an app, these utilities offer to remove associated files. Doing so won’t usually reclaim much space, but it will reduce the clutter in your Library folder, and it might remove a cache or media folder you didn’t even know existed.

5: Delete macOS Installers

Sort the Applications folder by name and delete macOS installers, whose names usually start with “Install macOS.” If you think you might need them again to install macOS in a virtual machine, archive them to an external drive or download them again.

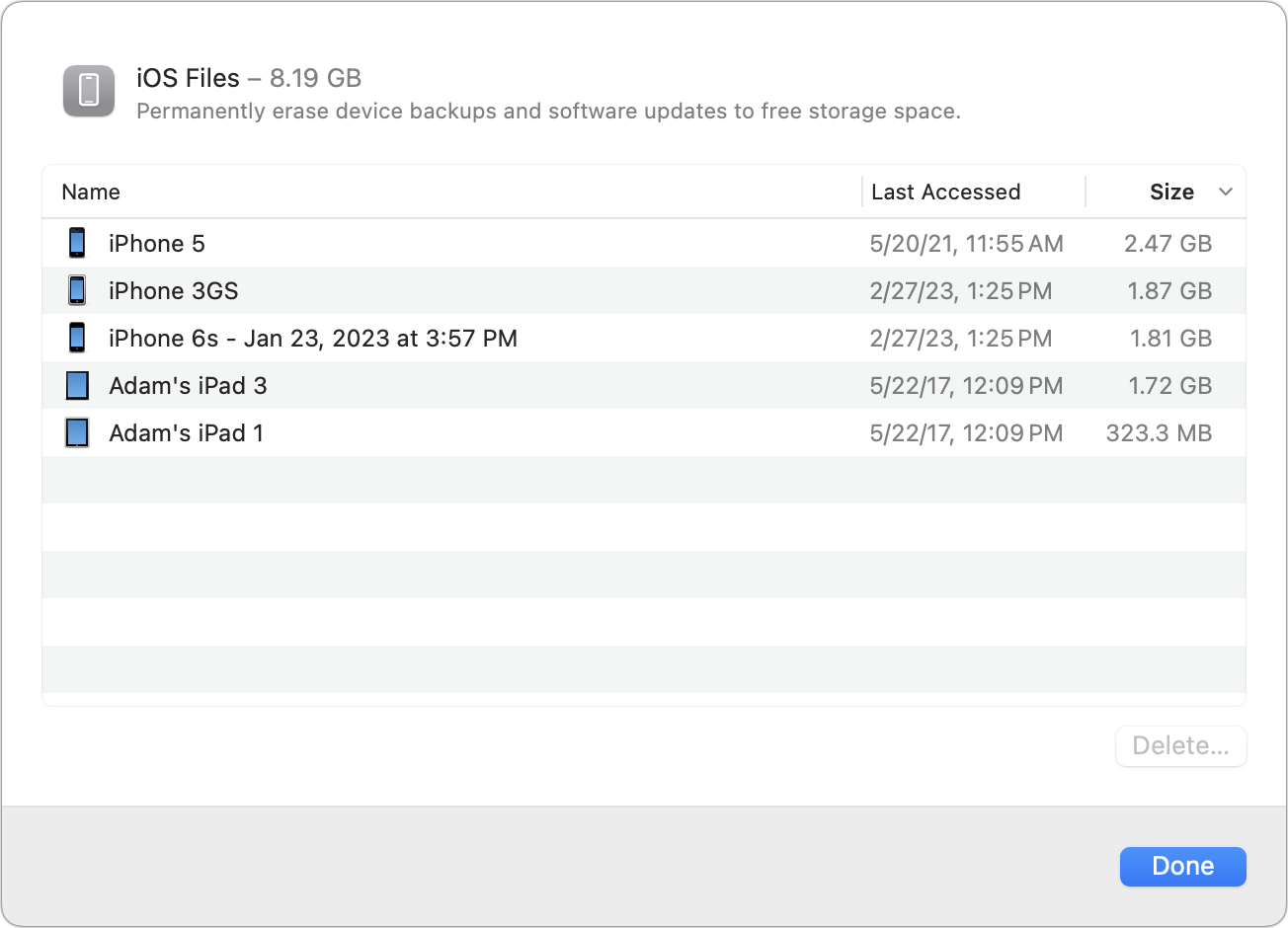

6: Delete old iPhone and iPad Backups

If you ever backed up an iPhone or iPad to your Mac, those backups may still be eating many gigabytes of storage space even if you’ve switched to backing up to iCloud. In System Settings > General > Storage > iOS Files, you can see how many backups you have and delete unnecessary ones. If you want to switch to iCloud for iPhone and iPad backups, make sure you have enough iCloud+ storage space and then turn on backups on your devices in Settings > Your Name > iCloud > iCloud Backup. These old backups will also appear in scanning utilities like GrandPerspective and OmniDiskSweeper, as mentioned in Step 3 above, but it’s easiest and safest to delete them using macOS’s native interface.

Those who have used iMazing may also see its backups and support files here, and they can also be deleted if you’re no longer using those devices or iMazing itself.

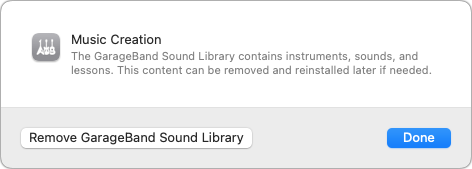

7: Remove the GarageBand Sound Library

During installation, GarageBand encourages you to install instruments and loops—first a 2 GB starter collection and then the complete 25 GB Sound Library. If you downloaded these files but are not actively using them, it’s safe to remove them because you can always get them again later from the GarageBand > Sound Library menu. To reclaim the space they occupy, open System Settings > General > Storage > Music Creation and click Remove GarageBand Sound Library.

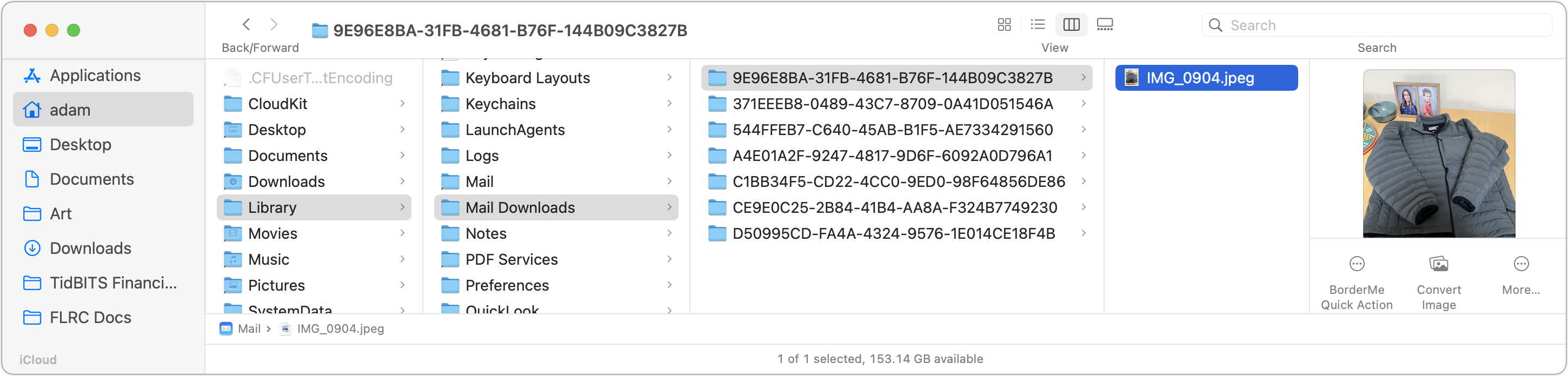

8: Remove Opened Mail Attachments

In Apple’s Mail, when you open an attachment, it extracts a copy of the file from the MIME-encoded message and stores it locally in a cryptically named folder at the path below. Or at least it does for me and many others—some seem to have nothing at that location, as discussed in TidBITS Talk. To view the contents of that folder, copy the path below, switch to the Finder, choose Go > Go to Folder, and paste this path.

~/Library/Containers/com.apple.mail/Data/Library/Mail Downloads

It’s unclear why Apple extracts attachments in this way, but since the attachments remain in the original messages, there’s no harm in deleting them. Some people reported finding gigabytes of files in there.

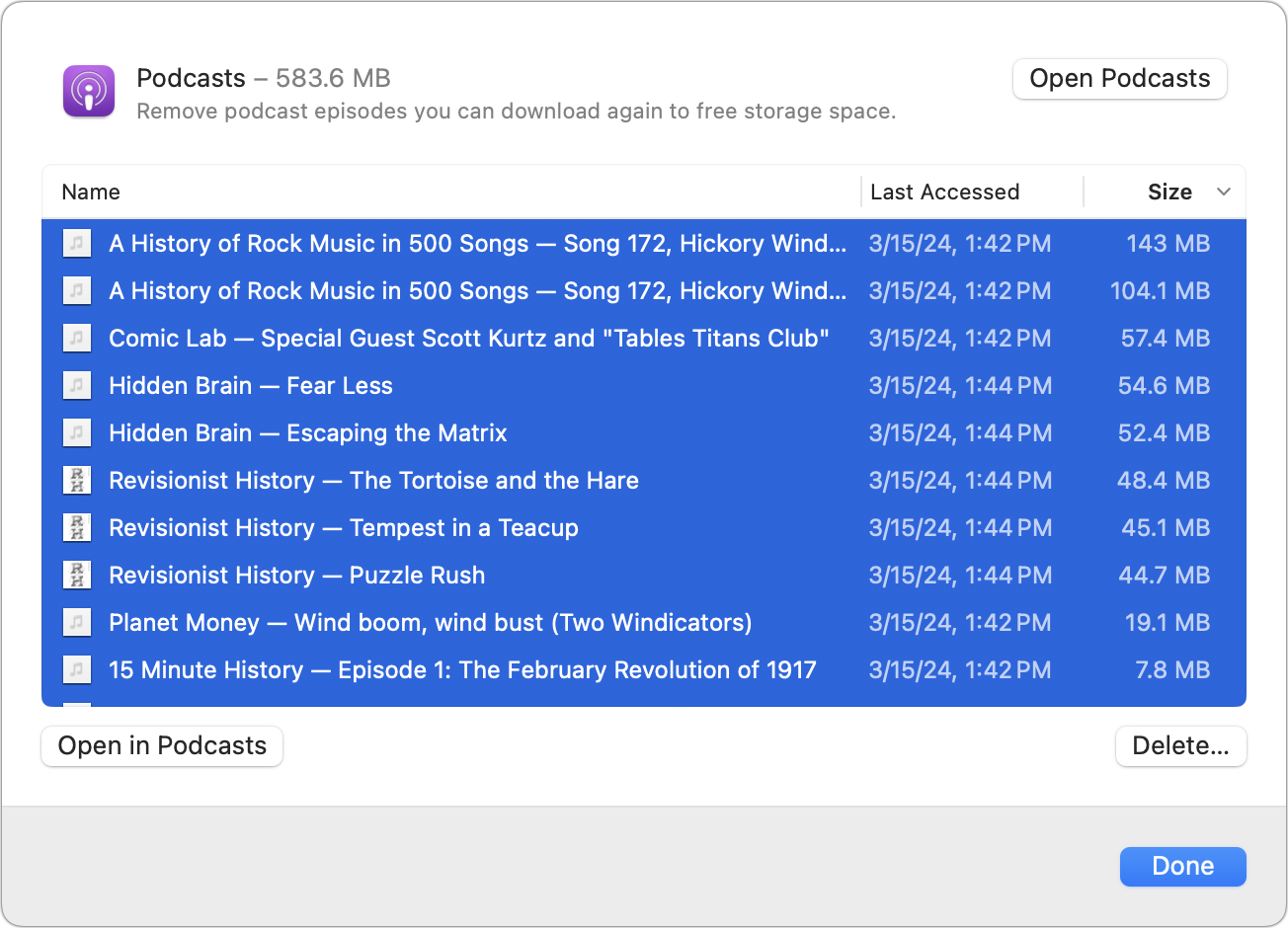

9: Remove Unwanted Podcasts

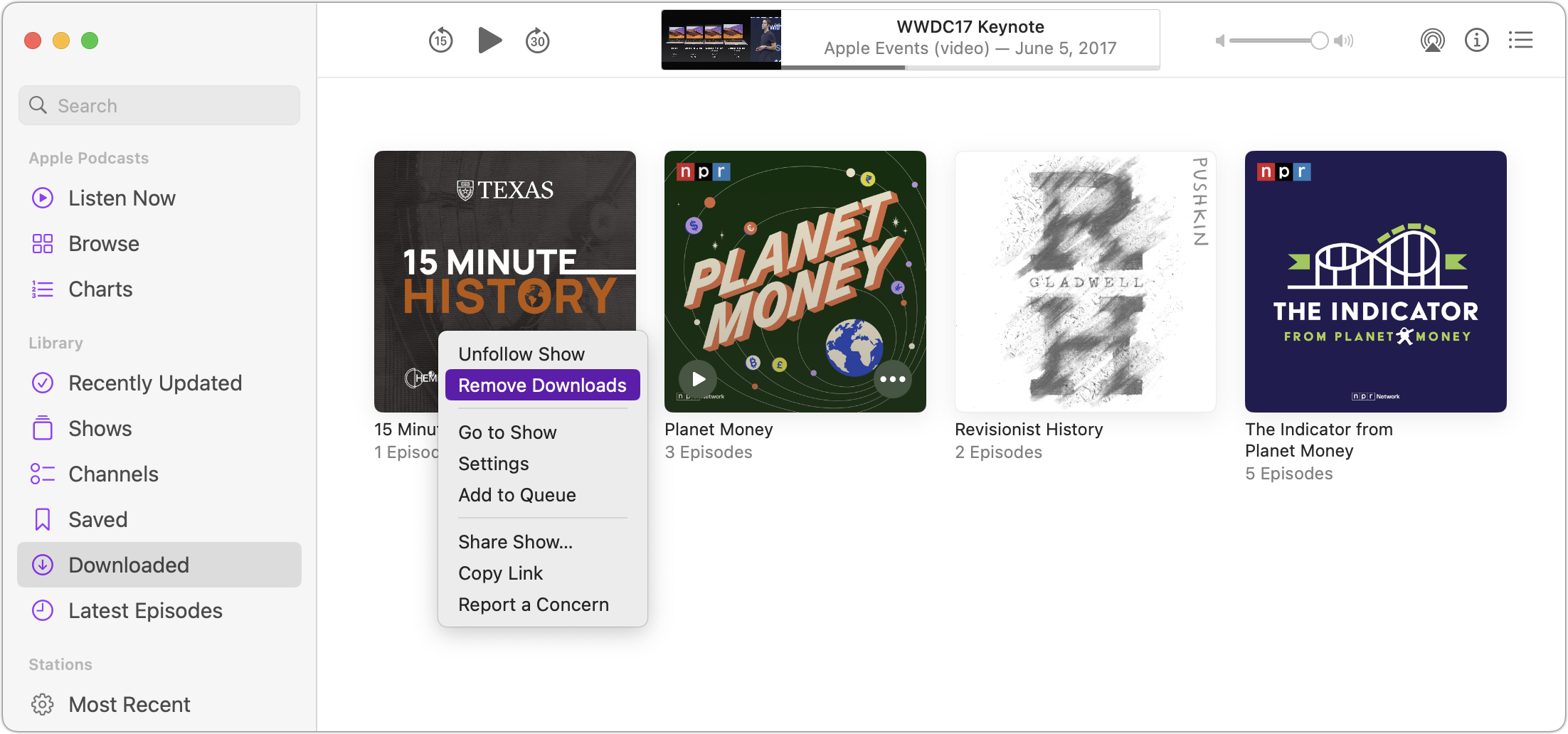

If you followed some shows in Apple’s Podcasts app but then stopped listening or switched to another podcast app or platform, the Podcasts app may have accumulated a lot of cruft you never intended to consume. To recover that space, open System Settings > General > Storage > Podcasts, select all the extra podcast episodes, and click Delete.

For a more focused approach, click Downloaded in the sidebar in Podcasts, Control-click each unwanted podcast, and choose Remove Downloads. Either way, make sure to set the downloading options appropriately in Podcasts > Settings > General. If you never want to listen to future episodes, choose Unfollow Show and then click Remove From Library to everything associated with the podcast.

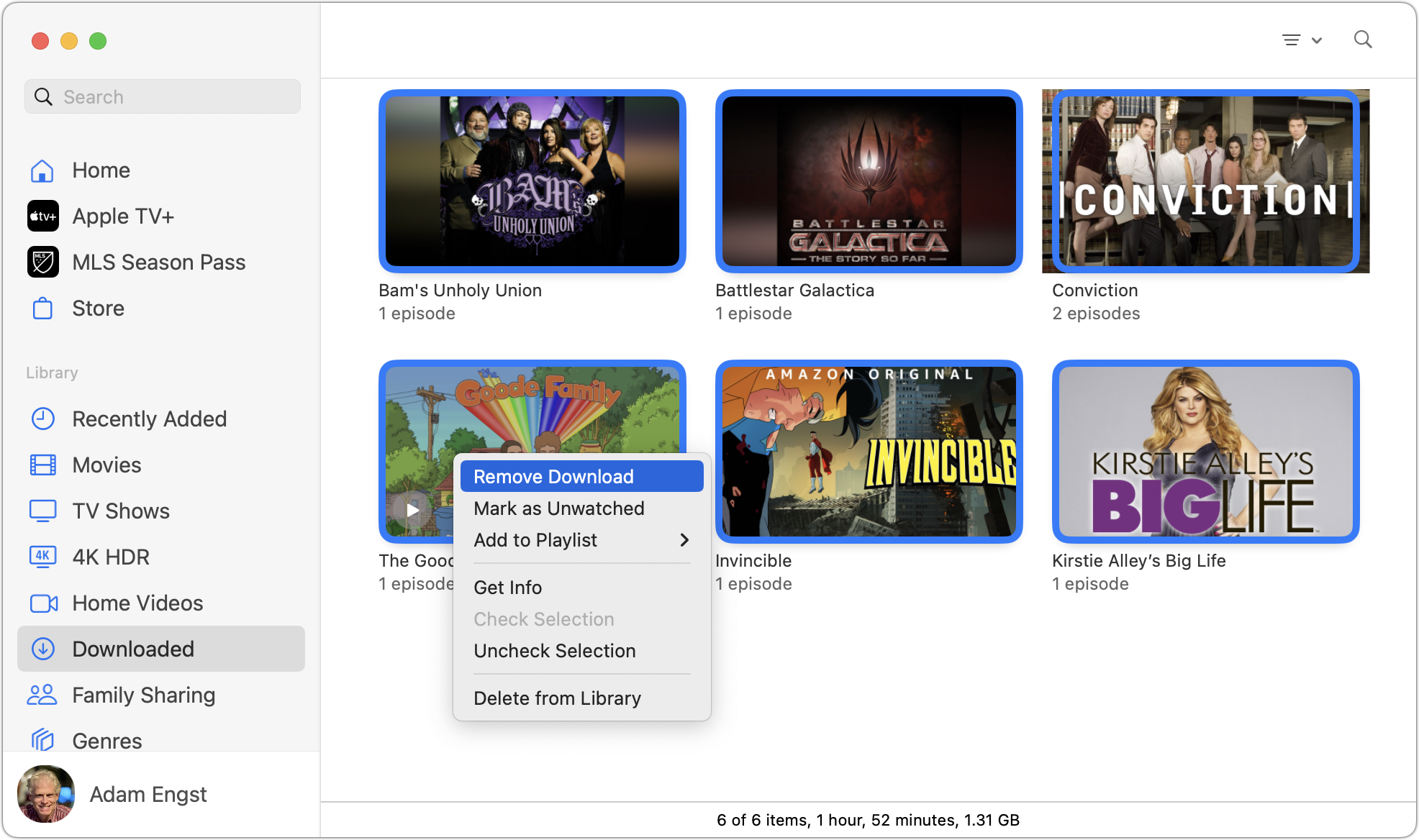

10: Remove Watched TV Shows and Movies

We’re starting to get into trickier territory here because not all movies and TV shows in the TV app can be downloaded again. To remove those that can easily be recovered, click Downloaded, select all, Control-click one of them, and choose Remove Download. (In my testing, the TV option in the System Settings Storage screen didn’t see all the downloads.)

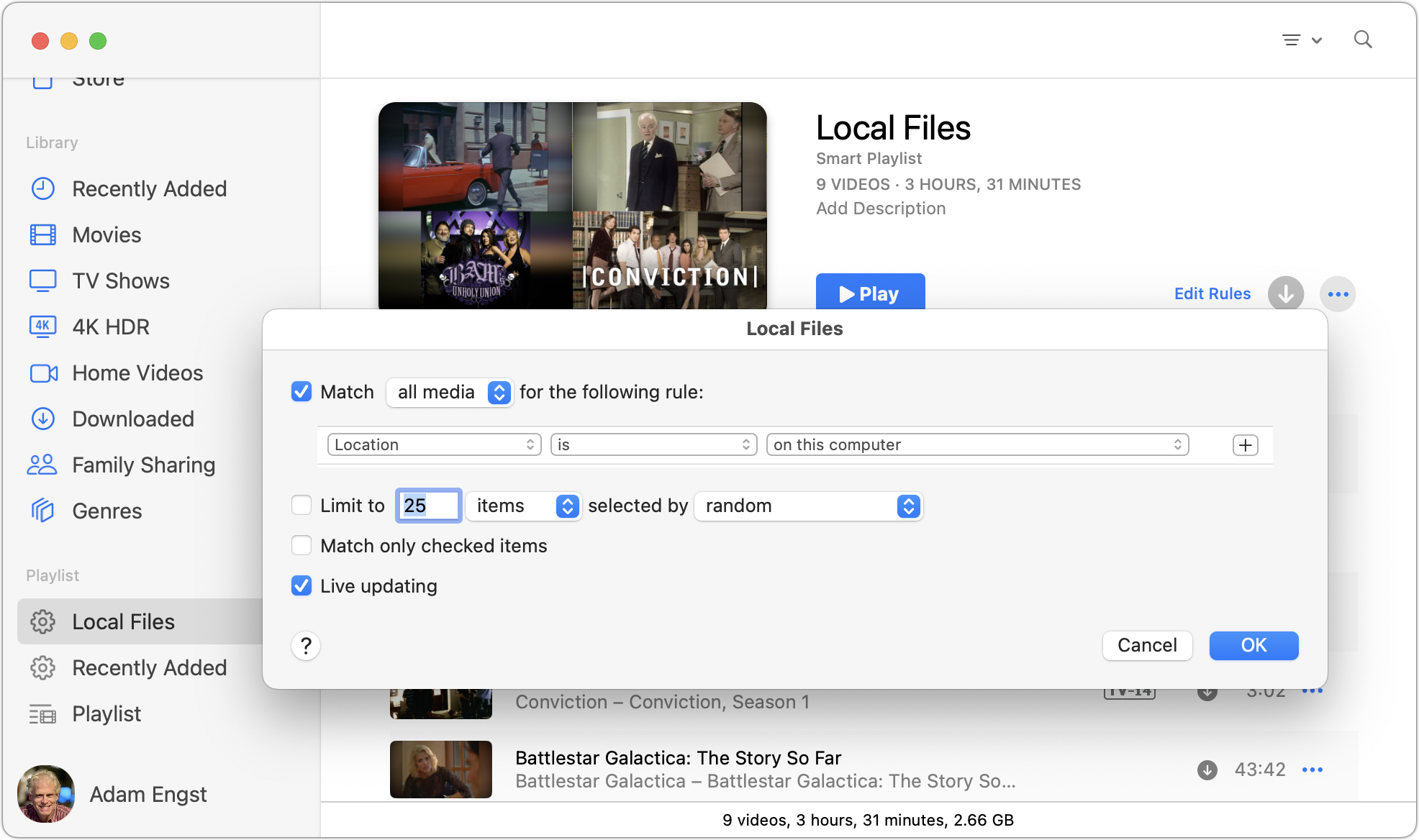

If manually added TV shows and movies are consuming space, create a smart playlist with a Location rule for items on the computer. To delete the files it collects, select them, Control-click one, and choose Delete from Library. Remember that you won’t be able to redownload such videos, so delete them only if they’re archived elsewhere or you don’t want to watch them again.

11: Remove Downloaded Copies of Apple Music and iTunes Match Songs

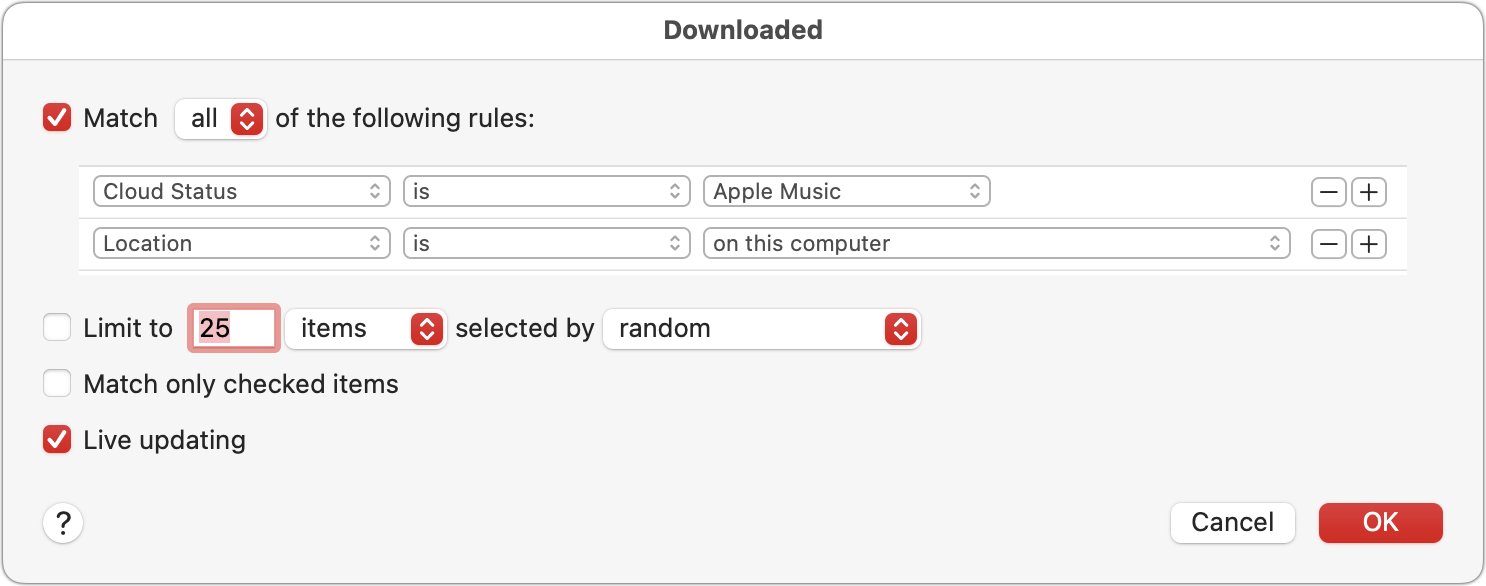

Just as you can remove downloaded video files in the TV app, you can also remove downloaded songs in the Music app. For some reason, the Music option in the System Settings Storage screen can only see and remove music videos, not regular tracks, but the smart playlist approach works for Music, too. Create a new smart playlist with a Cloud Status rule that matches either Apple Music or Matched (for iTunes Match) and a Location rule that looks for items on the computer. Then select everything it finds, Control-click one of them, and choose Remove Download. The Cloud Status rule is vital to avoid deleting music that exists only locally.

12: Remove Local Copies of Apple Books

I find Books the hardest to work with all of Apple’s media apps, but that may be related to it accumulating random test files over the years. (I’ve never regularly used it to read books—I prefer borrowing ebooks in Libby; see “Skip the Library Trip, Borrow Ebooks and More at Home,” 14 September 2020.)

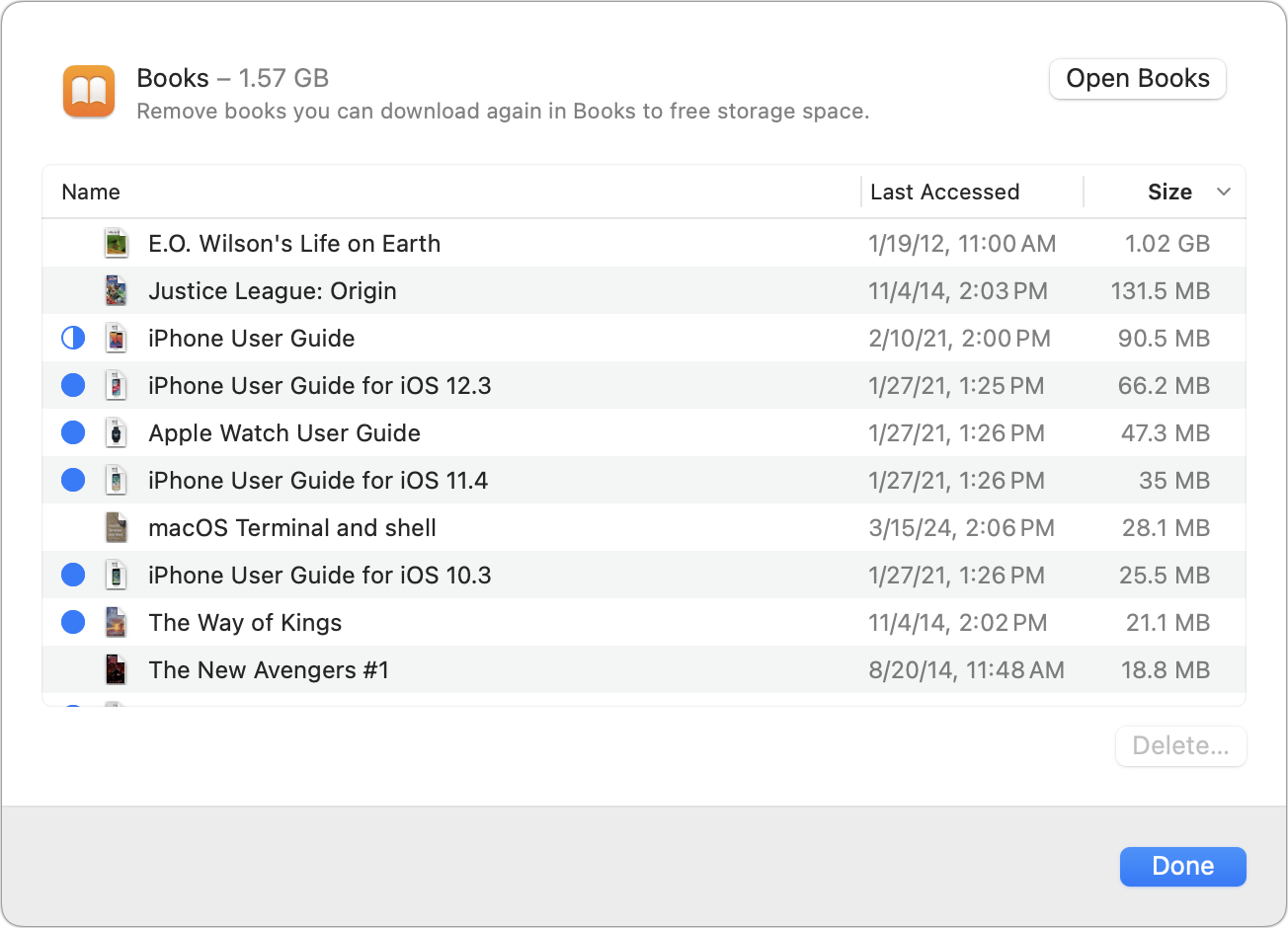

Apple makes it straightforward to remove downloads for books you’ve purchased from Apple Books (previously the iBookstore). Open System Settings > General > Storage > Books, select the books you don’t want, and click Delete.

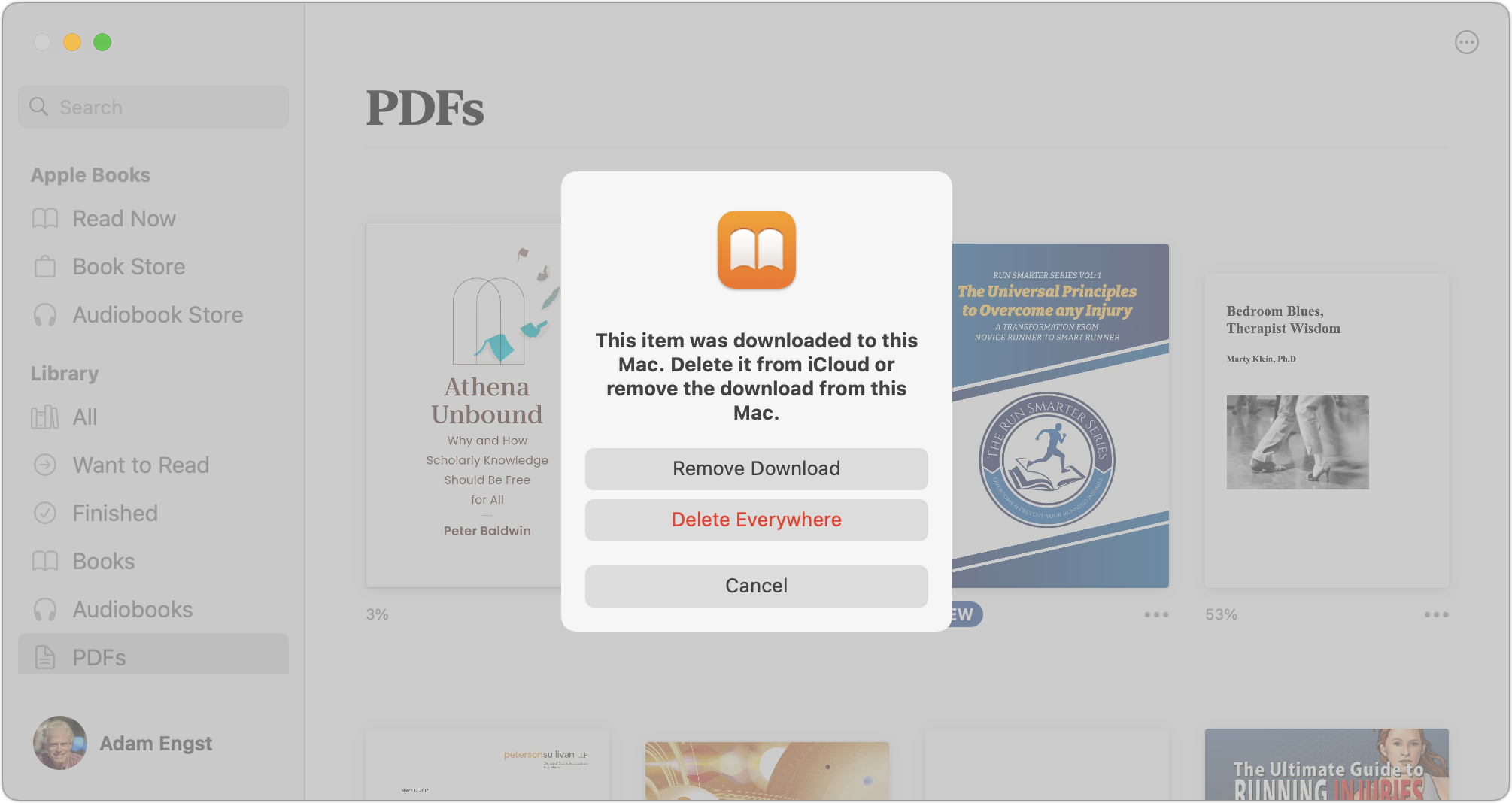

However, you could also have added large EPUB or PDF books to Books and synced them through iCloud. You can select one or more items in Books, Control-click one of them, choose Remove, and then click Remove Download. That’s unsatisfying because I could never figure out where the downloaded files lived to verify that they were actually being deleted. The only location I could find was iCloud Drive/Books, and I could view the contents of that folder only by double-clicking a PDF book to open it in Preview, Control-clicking the filename at the top of the window, and choosing the Books folder. But deleting a file from that folder deletes it from Books, too—it’s the same as clicking Delete Everywhere below and does not merely remove a download. Be careful.

13: Select Optimize Mac Storage and Remove Local iCloud Drive Files

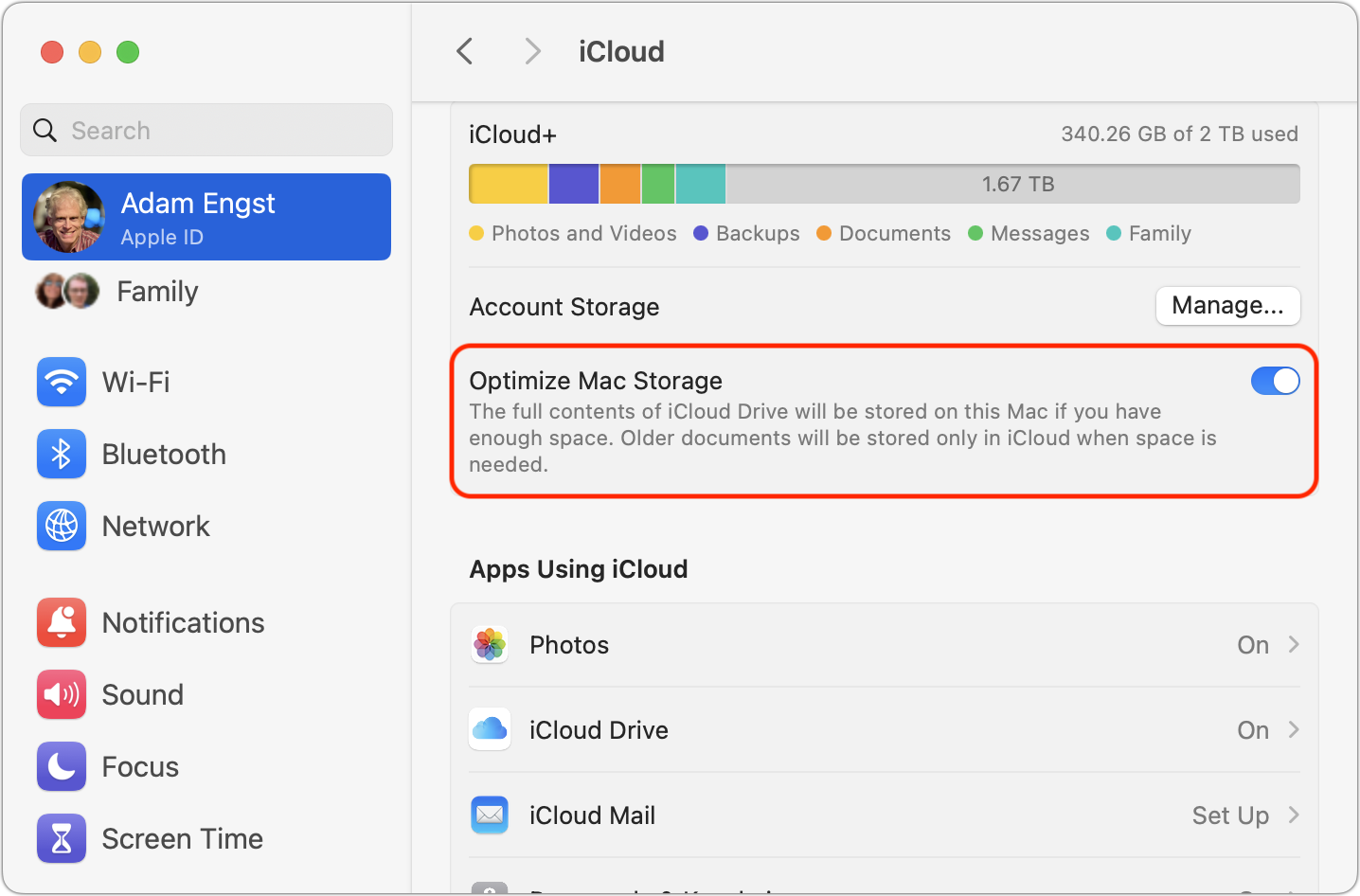

If you store large quantities of data in iCloud Drive, the local copies may consume a lot of space on your Mac’s drive. Because you can always download those files from iCloud Drive again, it’s safe to turn on System Settings > Your Name > iCloud > Optimize Mac Storage. Then, Control-click folders and choose Remove Downloads. Of course, cloud-only files won’t be backed up locally, but they should have been backed up before you turned on Optimize Mac Storage, and any files you modify or create will be local (at least for a while) and will thus be backed up.

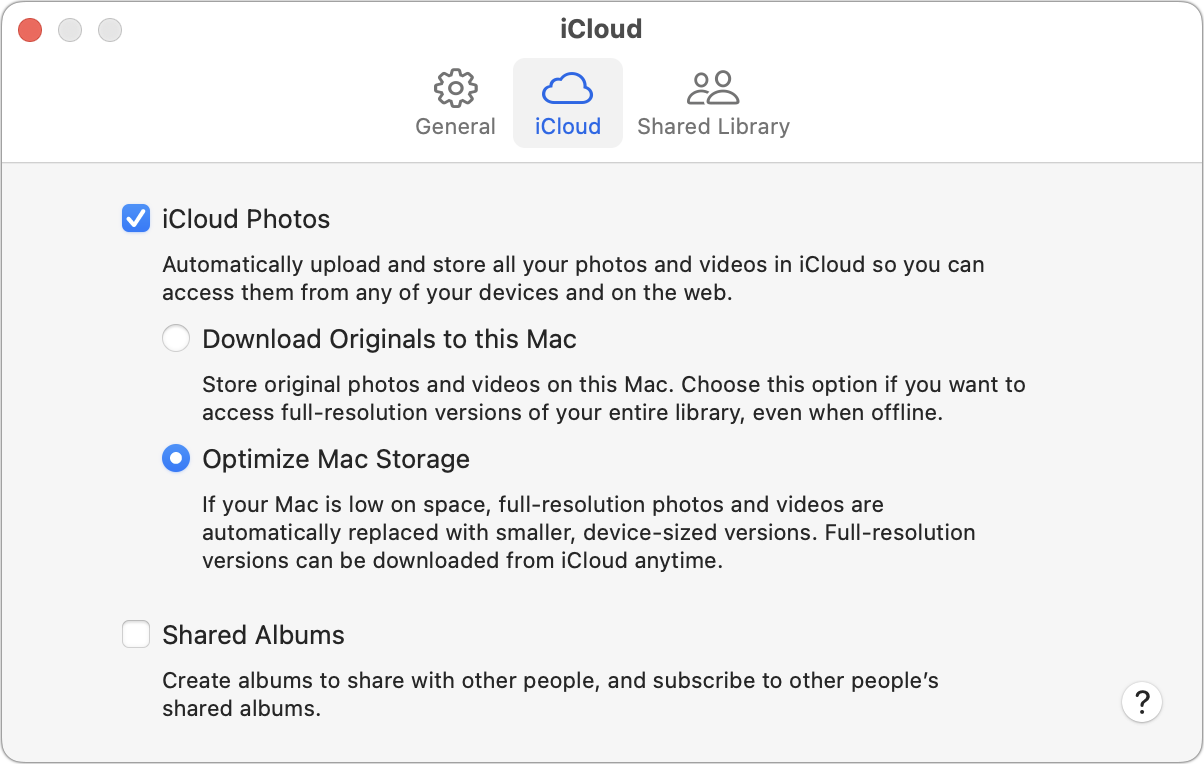

Conceptually similar is the option in Photos > Settings > iCloud to Optimize Mac Storage. As Apple says, it replaces full-resolution photos and videos with smaller, device-sized versions. Whenever you open a photo or video, Photos automatically downloads the full-resolution version from iCloud. You can turn this option on, and I’ve done that on my MacBook Air.

However, I would caution you about two things if you’re trying to clear space:

- Photos doesn’t provide a manual way to remove downloaded photos and retain just a placeholder. Space management happens automatically, so you shouldn’t expect to recover space immediately after enabling Optimize Mac Storage. However, turning it on will alert macOS that it can evict originals, so error conditions caused by low space may go away.

- Although I trust iCloud Photos insofar as I trust Apple’s ability to maintain the integrity of my files stored in its cloud services, I also want a local backup of the full-resolution images and videos because of the downside of a rare glitch deleting a lifetime of memories. There’s no way to create a local backup of iCloud Photos when Optimize Mac Storage is active. That’s why I use that setting only on my MacBook Air; I have my iMac set to “Download Originals to this Mac” for backup and better performance.

Although this is venturing into the weeds, if you use Box, Dropbox, Google Drive, or another cloud storage service, it almost certainly has an option to remove local copies of files. That may or may not be generally desirable, but if you’re trying to clear a bunch of space quickly, it will do so without permanently deleting any data.

14: Delete iPhoto Libraries

Although iPhoto has been dead and gone for many years, you could still have an iPhoto library on your drive because there was no prompt or migration path that deleted these libraries after you started using Photos. Assuming that you’ve migrated its contents to Photos (the package will have a .migratedphotolibrary extension), it’s safe to remove the iPhoto library.

However, you may not save much space. Apple uses Unix hard links to store the same master images in both iPhoto and Photos. Migrating from iPhoto to Photos doesn’t copy files from the iPhotos library—it adds new hard links. Likewise, deleting an iPhoto library doesn’t remove the hard-linked files from the drive, as those files exist independently of any single link. (Hard-linked files are deleted only when all hard links to them are deleted.) On TidBITS Talk, David C. explained how this works in detail, and when I looked back to see what we had written about it in TidBITS, I ran across Jason Snell’s article, “Initial Impressions of Photos for OS X Beta” (9 February 2015), which links to a Six Colors article explaining more about the hard links.

15: Delete Time Machine Snapshots

Today’s Time Machine leverages local APFS snapshots, generating one every hour and keeping the last day’s worth so you can restore recent files from Time Machine even if your backup drive isn’t available. Although these snapshots are of your entire volume, the magic of APFS means that each contains only the data that has changed since the previous one. This also means that if you download a huge amount of data in a single day, that data is essentially doubled by the snapshot!

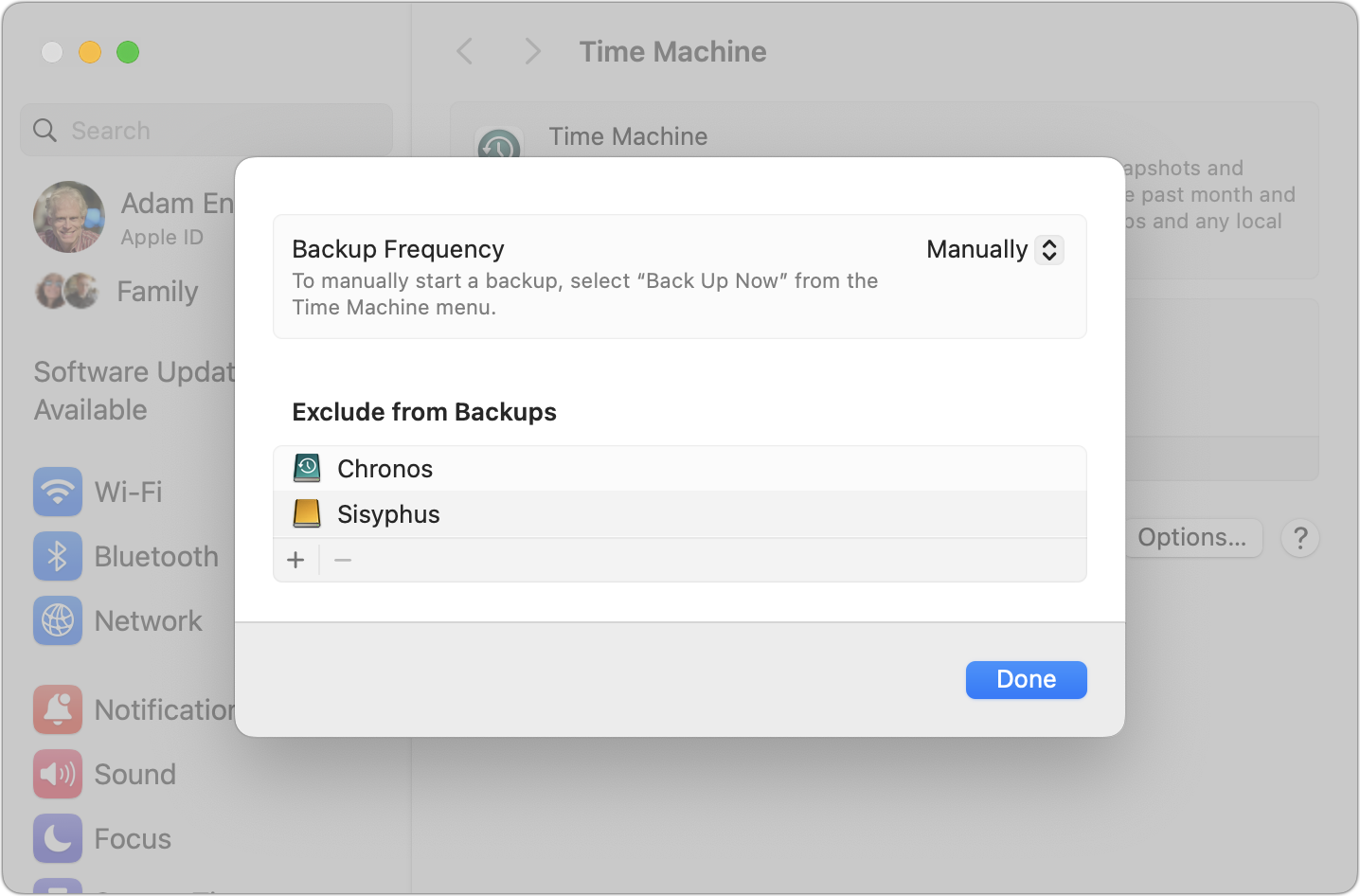

If you need to recover space temporarily, you can delete these snapshots. Apple recommends doing this by turning off automatic backups: open System Settings > General > Time Machine > Options, and set Backup Frequency to Manually. Make sure to turn automatic backups back on later—any sort of manual selection of files or backup triggering leaves open the possibility of not having a backup when you need it. Although Apple says the snapshots will be deleted in a few minutes, that didn’t seem to happen in my testing.

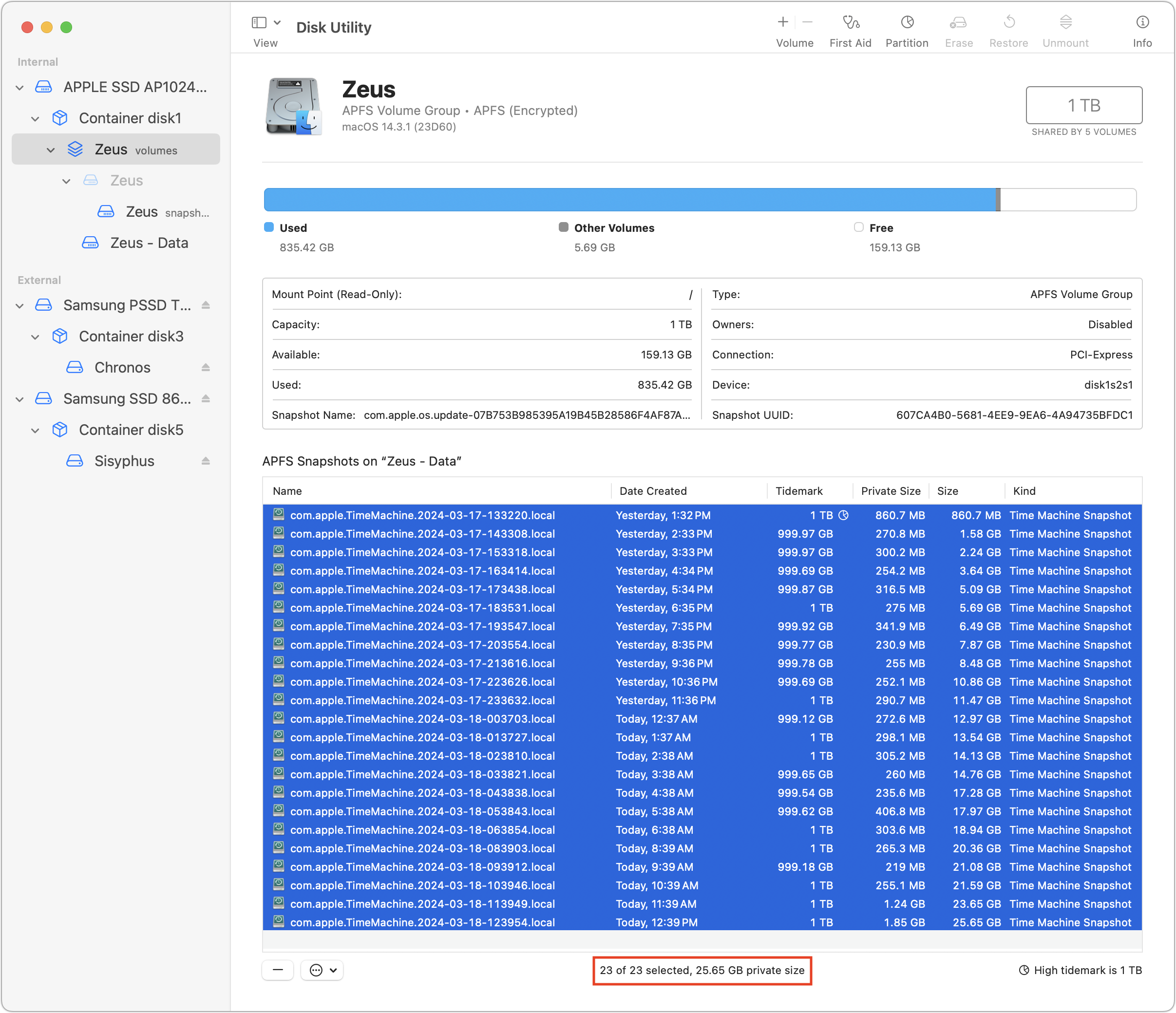

For more direct manipulation and immediate gratification, work in Disk Utility. Select your startup drive’s volume, and delete snapshots by selecting all of them, Control-clicking one, and choosing Delete.

I don’t recommend deleting Time Machine snapshots other than in exceptional circumstances for three reasons:

- Even though the snapshots are on your startup drive, deleting them seems to prevent the Time Machine interface from showing data that has been copied to your external Time Machine drive. If you need to recover something from the time covered by the snapshots, you may be able to do that by manually browsing each Time Machine backup folder in the Finder.

- Theoretically, you can see how much space deleting snapshots will save by selecting all the snapshots and looking at the private size number at the bottom of the screen. I’m not confident that will always be the case, but it will give you a ballpark figure.

- This approach to saving space works only temporarily because Time Machine will recreate these snapshots as it runs.

All that said, it may be worth checking Disk Utility to see if there are orphaned Time Machine snapshots taking up space unnecessarily.

16: Delete Unwanted Contents of the Downloads Folder

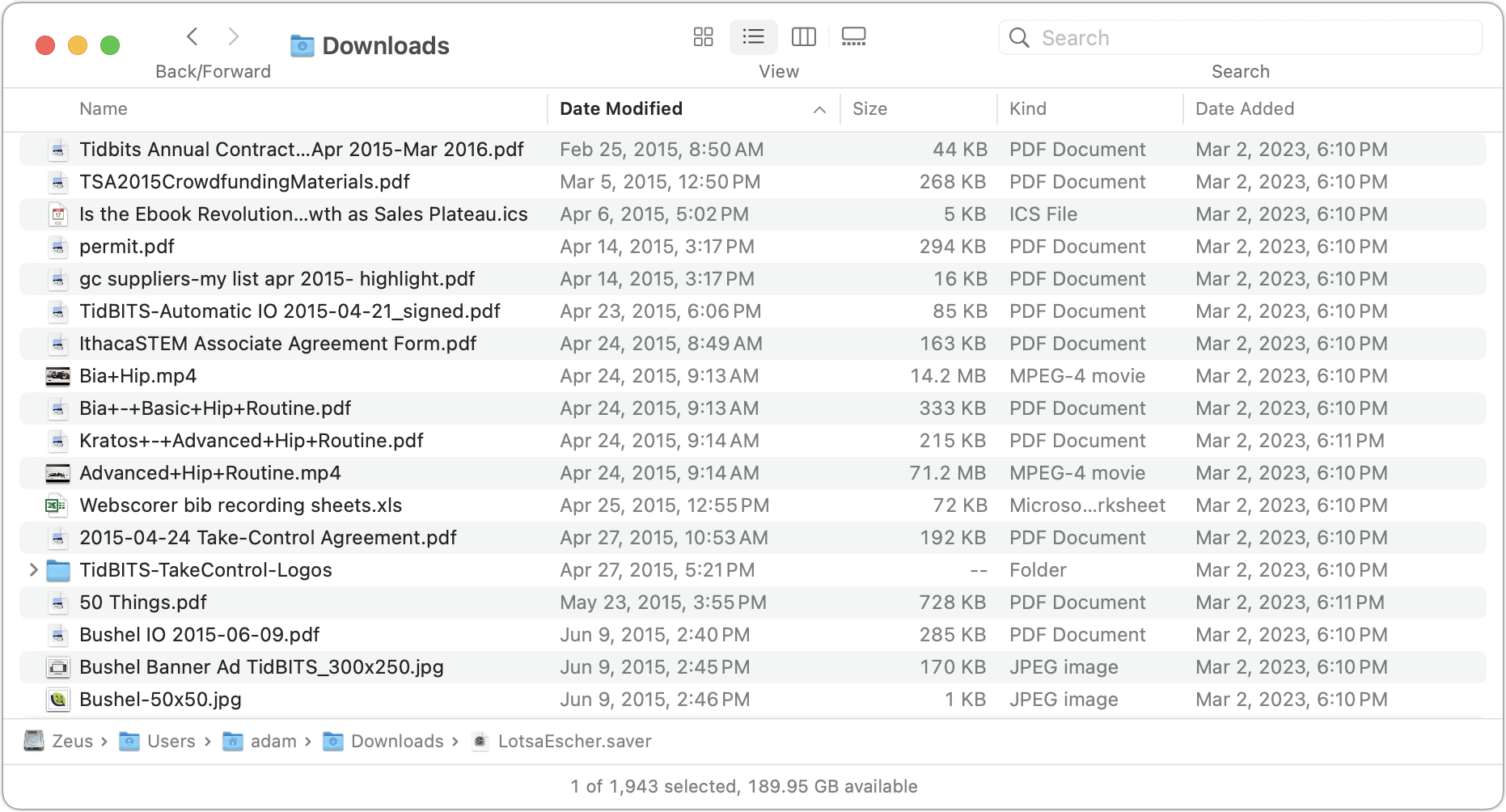

Many of us haven’t established a routine of deleting downloaded files we never need again. I’m terrible about this—my Downloads folder currently holds 1943 files occupying over 16 GB of space. If you’re sure you don’t need any of these files, you could choose File > Select All and drag them to the Trash.

But if you might need some recently downloaded files, consider sorting the Downloads folder by the Date Modified column in List View, then delete all the files that were last modified more than a year ago. Embarrassingly, I still have downloads from 2015.

Of course, if you have files or apps in your Downloads folder that you regularly use, don’t delete them. I think it’s dangerous to keep anything important in the Downloads folder—there’s no reason not to move such files to more appropriate folders.

17: Delete Photo, Song, and File Duplicates

In theory, there’s no downside to deleting duplicates, but in my experience, it can require a fair amount of time to verify that what’s being deleted is genuinely a duplicate and isn’t desirable for some other reason, such as having the same file in multiple folder hierarchies.

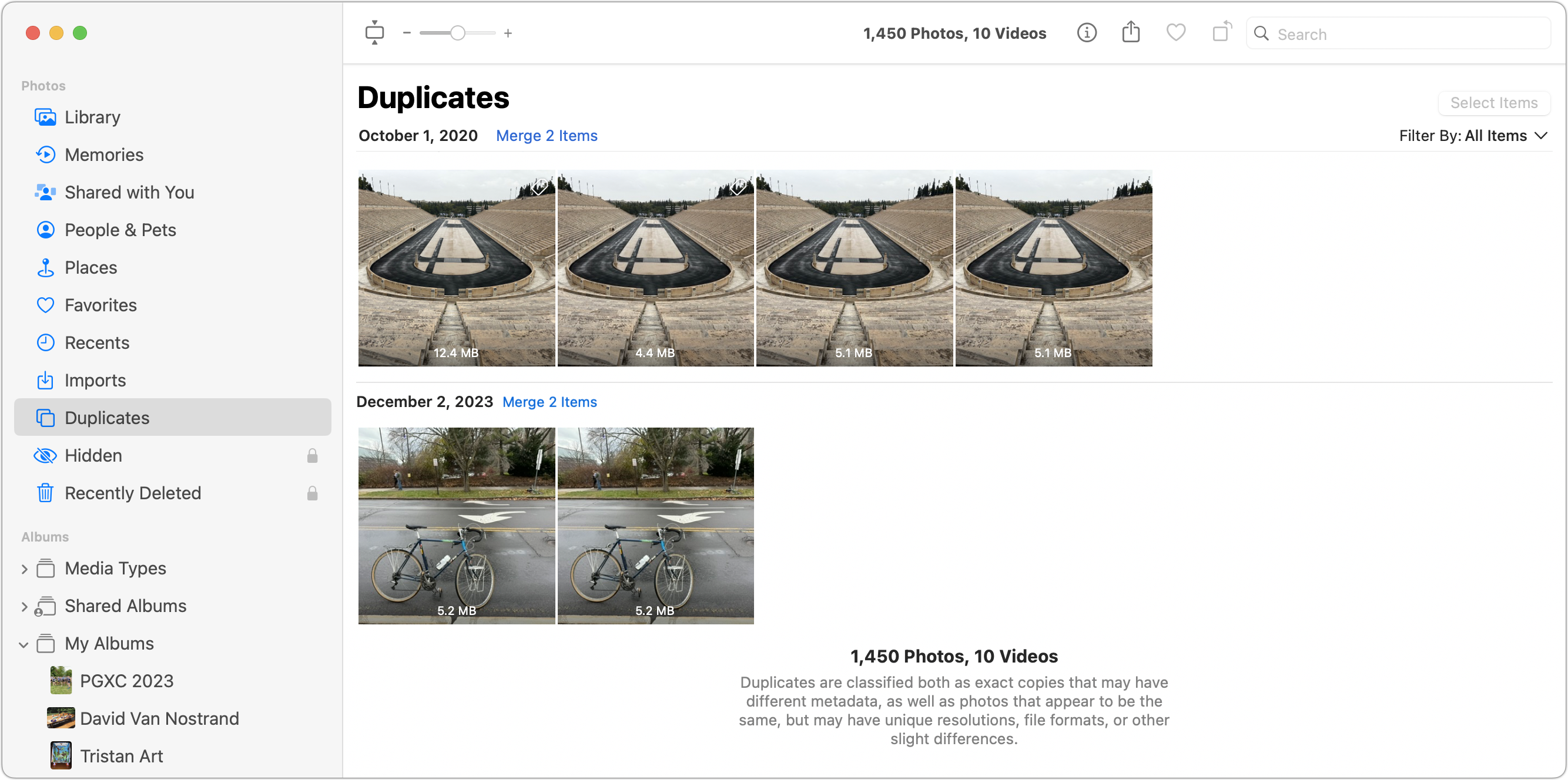

Nonetheless, it’s generally safe to use the duplicate removal feature of Photos. Click Duplicates in the sidebar, select one or more sets of duplicates, and click either the Merge link above them or the Merge X Items button. Whether or not that saves significant space depends on your situation. Fat Cat Software’s $29.95 PowerPhotos may be easier to use or do a better job.

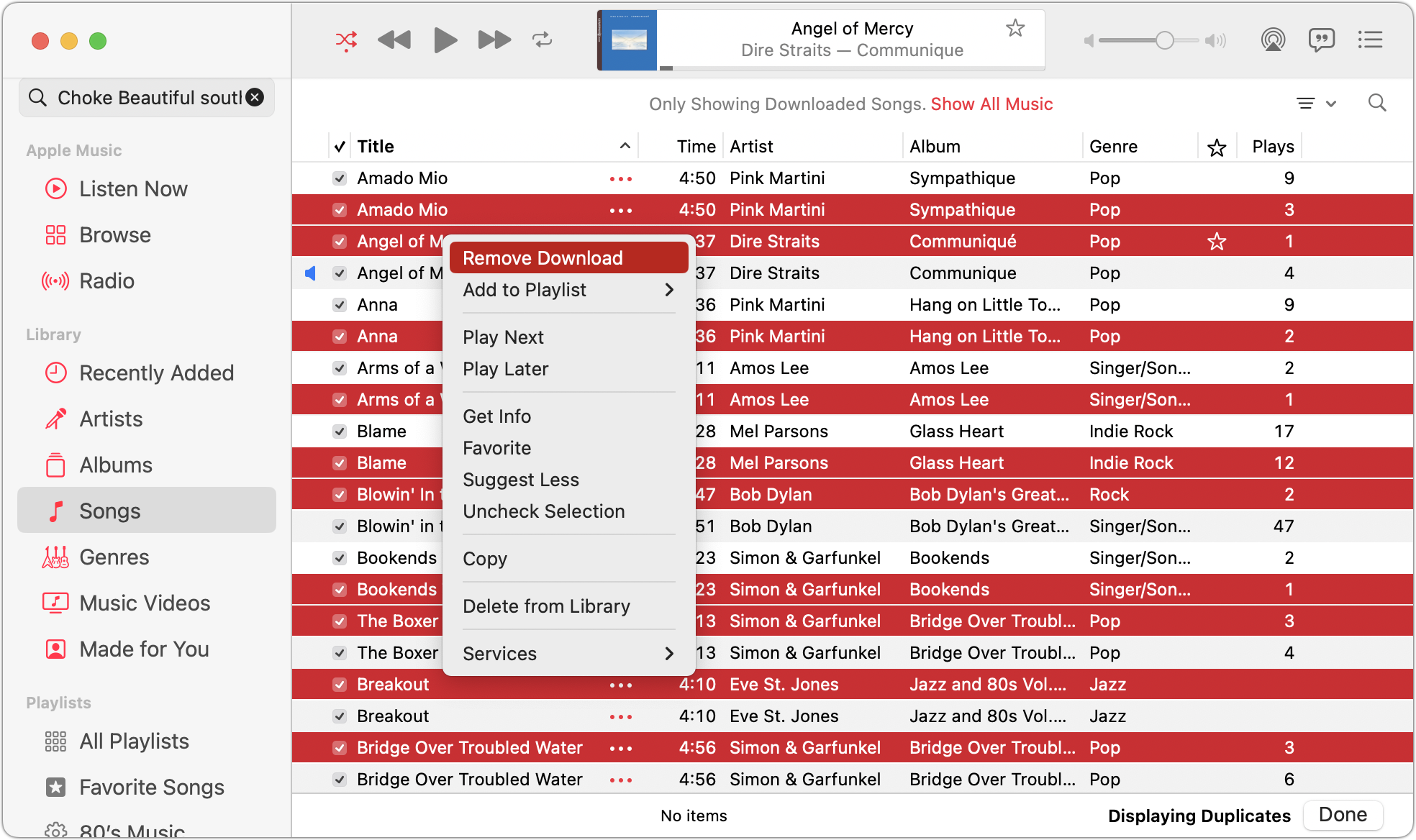

Although it can identify duplicates, Music provides no automated way to merge them like Photos. Click Songs in the sidebar, choose View Only Downloaded Music (since deleting Apple Music duplicates won’t save any space), hold down the Option key, and choose File > Library > Show Exact Duplicates to see duplicates whose downloads you might want to remove by Control-clicking and choosing Remove Download. I doubt most people will save much space by deleting duplicate songs.

Various utilities provide more general duplicate removal, but I’ve only used the $19.95 Gemini 2 from MacPaw; it’s also included in MacPaw’s Setapp service. It works pretty well when identifying duplicate images.

18: Delete Already-Imported Folders of Photos

Be very careful here. More than once, I’ve seen significant amounts of drive space consumed by leftover folders of photos that have already been imported into Photos, where the user wants them. If you can be certain those photos have been imported into Photos and copied into the Photos library (make sure Photos > Settings > General > Copy Items to the Photos library is selected), you can delete the folders. Moving the folders to an external drive or cloud storage service would be safer.

You could also reimport the folders of photos into Photos and then rely on the app’s duplicate-checking and removal features to ensure that you have everything in.

19: Use DevCleaner to Delete Xcode Caches

I mention this option near the end because most people don’t use Apple’s Xcode development environment. If you do, consider using DevCleaner to remove device support symbols, build archives, derived data, cached documentation, old simulator and device logs, and old documentation. I don’t use Xcode, so I can’t comment on how well it works.

20: Compress Large Files

If you have a collection of large files that you need to keep but don’t need to access regularly, you could consider compressing them. The easiest way would be to create a Zip archive by selecting a file or folder in the Finder and choosing File > Compress. That’s lossless—when you expand the files, they’ll be exactly as they were before being compressed. If compressing and expanding files manually sounds like a hassle, can we have a brief moment to remember DiskDoubler?

Those with video collections could consider using Handbrake to recompress the video files with a more efficient codec and tighter settings. Although such conversions can reduce the size of files by 75% or more, the process is lossy—the compressed data can never be recovered. Tread carefully!

21: Get External Storage

Finally, if you’ve gotten this far, you’re really bumping into the limits of your Mac’s internal storage. Since there’s no way to expand that for modern Macs, you’ll want to look into external storage, either an SSD or a hard drive. I’ve mentioned moving little-used data off to external storage a few times already, but if you have a massive Photos library you want to keep local, moving it to an external SSD can be a highly effective way of clearing space on your internal drive. Make sure you back up externally stored files as rigorously as you do your startup volume’s data!