#1545: Virtual CES 2021 kick off, new Apple privacy policies, pick meeting times with When2Meet

The first virtual CES kicks off this week, and our typically roving correspondent Jeff Porten is attending virtually to sniff out the coolest and most interesting gizmos and gadgets. This year, you can vote on which ones most interest you! Glenn Fleishman discusses Apple’s new privacy disclosure rules for App Store developers, which are sending Facebook into a tizzy. Finally, Adam Engst describes When2Meet, a simpler alternative to Doodle for helping a group decide on meeting time. Notable Mac app releases this week include Zoom 5.4.7, EagleFiler 1.9.2, Nisus Writer Pro 3.2.1, Timing 2021.1, Pixelmator Pro 2.0.3. BusyCal 3.12.2 and BusyContacts 1.5.1, BBEdit 13.5.4, Default Folder X 5.5.4, and Keyboard Maestro 9.2.

When2Meet: An Easier Way to Settle on a Meeting Time

For years, when I’ve wanted to schedule a meeting with an arbitrary set of people, I’ve relied on Doodle to select a mutually compatible date and time (see “Doodle Helps You Schedule Meetings,” 28 May 2015). It’s a useful, effective service that lets you specify a set of times for meetings and then enables people to say whether they can or cannot attend (or can attend, if necessary) at any particular time. When everyone has voted, you can scan the columns to determine which got the most votes and is thus the best time to meet.

However, since I ran across When2Meet, I haven’t used Doodle. Why? It’s faster and easier to create a When2Meet event, vote in it, and identify the best time. Add in the fact that When2Meet is free and limits itself to a single ad (in contrast to Doodle’s plethora of ads), and you end up with a compelling scheduling solution when you’re trying to herd cats into a meeting.

Create a When2Meet Event

Let’s take a pandemic-appropriate example and assume that I’m trying to set up an hour-long Zoom call for a committee meeting. With Doodle, I would have to figure out all the possibilities (9–10 AM, 10–11 AM, 1–2 PM, and so on), enable each of them as a separate voting option, and then repeat that for each possible day. Not difficult, but sufficiently tedious in both the creation and voting phases that you usually want to suggest times carefully.

With When2Meet, creating an event is much easier because you don’t specify precise times, just overall time ranges.

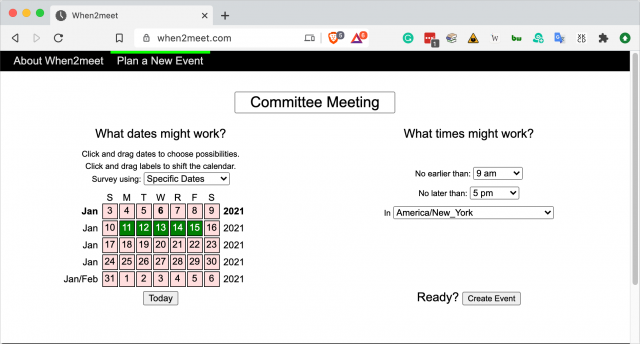

- Load the main When2Meet page.

- Type a name for your meeting at the top

- Click or drag to select the possible days for your meeting.

- Specify what the earliest and latest times should be, along with the time zone.

- Click Create Event.

That’s it. The hardest part is looking carefully at the grid of dates to make sure you’re selecting the correct ones. The current week appears at the top, so if you’re in the middle of the month, the grid may not match up with what you’d expect a calendar to look like.

Once you click Create Event, When2Meet creates your event and loads its voting page, which has a unique URL for sharing. It provides links for creating an email message or Facebook message, and it displays the URL in plain text as well. I always just copy the URL from my browser’s address field before sharing via email, a forum post, or text message.

Vote in a When2Meet Event

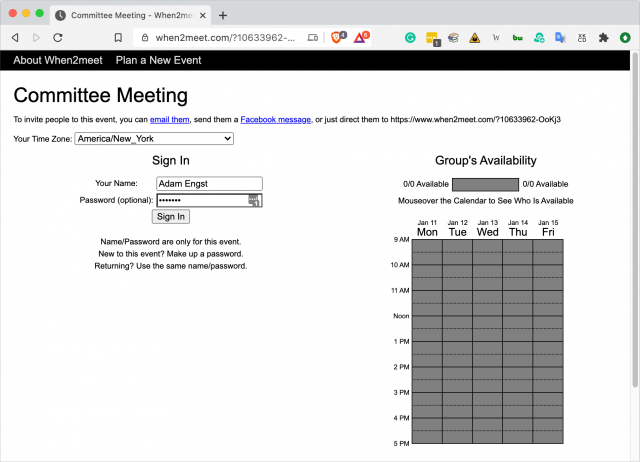

The voting experience is the same for everyone, even the person who creates the event. The first step is to sign in with a name that others will recognize and an optional password. The name and password combination is specific to this event and exists only to identify you in the event you want to change your vote. You could use easy throwaway passwords for different When2Meet events. I saved a login with a real password in LastPass, which auto-fills it automatically every time I vote in a When2Meet event.

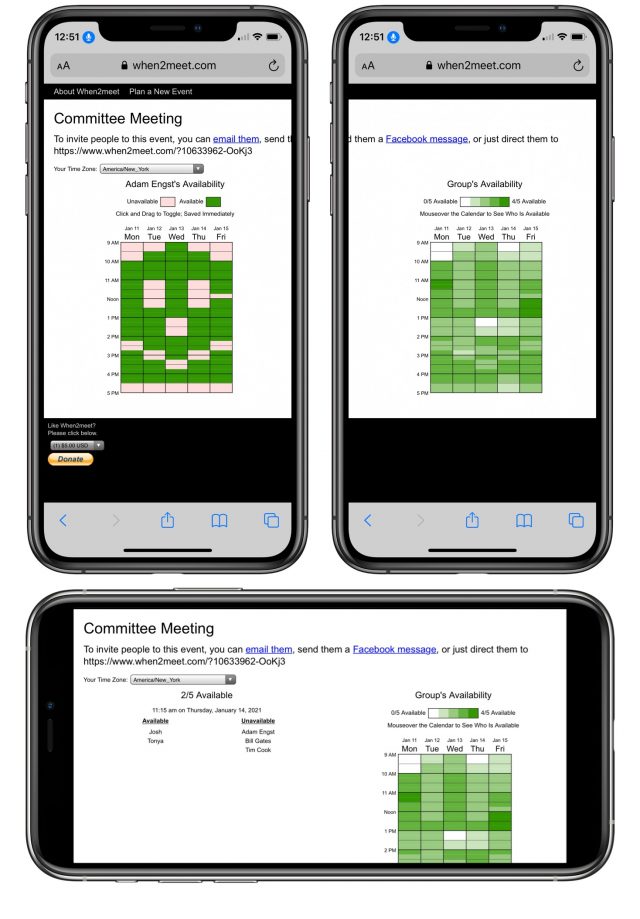

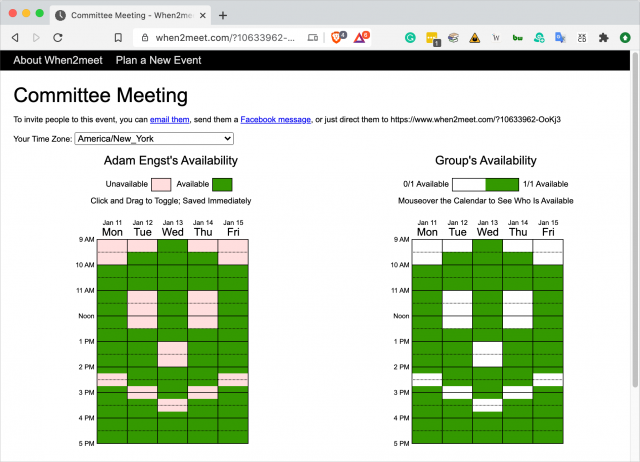

Once you’ve signed in, the left side of the When2Meet window displays a date-and-time grid that matches the Group Availability grid on the right side. Before you start selecting times, make sure the time zone matches yours—it should, but if you choose a different city from that pop-up menu, all the times adjust to reflect your local time.

To select times, you can either click or drag in your Availability grid. Clicking selects 15-minute blocks of time, whereas dragging horizontally or vertically allows you to select contiguous chunks quickly, turning them from red to green. If you accidentally include a bad time, click or drag over it to deselect.

I usually pull up my calendar and look back and forth at every day to see what might be going on. Then I select the times I’m available, making sure that I’m not voting for too-early morning times and leaving time for when I run at lunch on Tuesdays and Thursdays.

Again, that’s it. You don’t have to click a submit button or do anything else—just close the window.

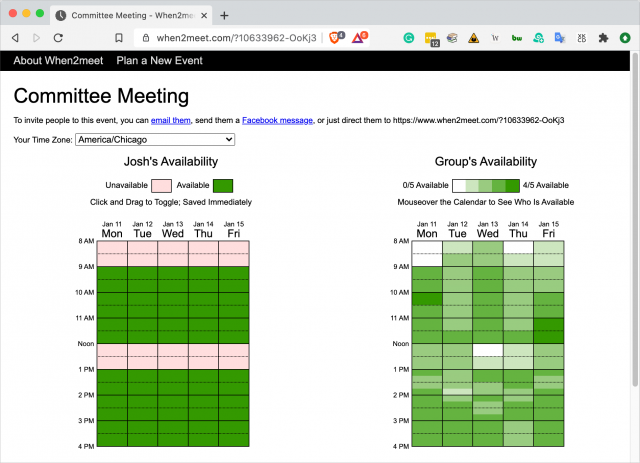

The experience is a little different for those who vote after the first person because they can see trends in the Group Availability grid on the right, as indicated by darker green blocks. In this fictional example, Josh is voting (note how I’ve switched his time zone to Central Standard Time), and he can see that he’s the fifth person to vote and that Friday from 11–12 AM his time is the leading hour-long contender. He can thus take that into account when specifying his availability.

What’s most important about this process is that it lets the group identify the best possible times without the organizer having to guess at them ahead of time. With Doodle, voting is enough of an effort that you try to guess at those times that are likely to work to reduce the number of voting clicks each person has to make. With When2Meet, voting is so easy that all times can be up for grabs, and the varying popularity of different blocks quickly becomes apparent.

Identify the Best Time in a When2Meet Event

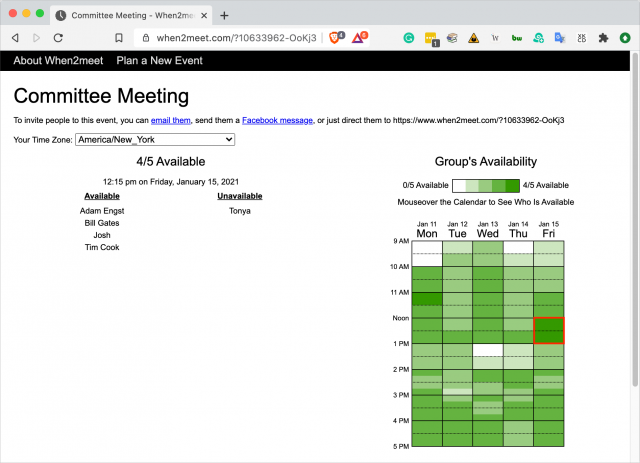

The organizer of a When2Meet event isn’t special—they can’t adjust other people’s votes or close voting or anything else. But every event has an organizer who will likely take responsibility for declaring the winning time. In this case, since I’m scheduling an hour-long Zoom meeting and there’s only one hour-long block that four of five participants could make, that’s the obvious choice to pick and communicate to everyone.

But what if there were multiple possibilities with the same number of votes? Or, as is often the case, what if some people are more important to have in the meeting than others? If the most popular option doesn’t include those people, you can’t go by color alone. Here’s the solution, and it’s something that any participant can do at any time.

Mouse over any block in the Group Availability grid on the right to make When2Meet display the list of who is and is not available on the left. As you can imagine, Tim Cook and Bill Gates are hard to pin down, so we’ll have to suffer with the fact that Tonya has a conflict for Friday from 12–1 PM.

And for a third time, I have to say, that’s it. Create an event, gather votes, pick a winning time, and you’re done.

The process could be faster if When2Meet guessed at possible times based on your calendar. However, that would require setting up an account and connecting your calendar, and then the developers would have to provide support for people who lost their passwords or whose accounts weren’t working and so on. Such integration wouldn’t be worth it—When2Meet is brilliantly lightweight now and does precisely what it promises—no more, no less.

I’ve used When2Meet entirely on the Mac, but in testing, it seems to work fine on an iPhone, albeit without a responsive display. It was easy enough to zoom the iPhone display in portrait orientation to vote and to see the Group Availability grid. Flipping the iPhone into landscape orientation made it possible to tap blocks and see who was available when.

When2Meet is free, but you can donate $5, $10, or $20 through PayPal if it’s valuable to you, as it has been for me, in time savings alone. If you’re trying to find the best time for a family Zoom call, a club’s committee meeting, or any similar scenario, give it a try.

CES 2021: Pre-Show Virtual Events Feature Game Cubes, Telepresence Robots, and Disinfecting Alarm Clocks

It’s that time of the year when I normally greet you from “fabulous Las Vegas” with news from the annual CES exhibition. But this year, I’m writing from my undisclosed location in Philadelphia because CES is entirely virtual. That’s a bit ironic for a show where “disruption” is every fourth word out of a marketer’s mouth: seeing that exact thing happen to its fifty-year-old format.

The Consumer Technology Association, which runs the show, is doing its best to dress this change up as merely a variation on business as usual. Still, I have no idea how the virtual show will go, and I don’t know how it will affect my ability to highlight the mix of wonderful, weird, and woeful that I typically see. Having attended the show roughly 20 times, I can scan several hundred booths in an hour, giving each one a brief opportunity to strike me as novel and worth more time. Compare that to the screenshot below, which appears to be the booth experience this year, unless it changes when the doors officially open on 11 January 2021.

Clearly, someone understands that no one will browse nearly 2000 exhibitors this way, so CTA “helpfully” put a randomizer on its home page.

That’s all very nice, but I don’t know what backwards-FE in a blue circle stands for and I shouldn’t have to. I can’t believe CTA didn’t figure this out, but vertical business cards bearing logos don’t replicate the exhibition experience. It could have been better simulated by giving each “booth” space for four thumbnails and text the length of two tweets, and then letting each exhibitor do whatever they pleased with that to get me to click on their card.

Beyond that, so much of the value of CES is being there. Whether it’s getting hands-on with a production model that won’t be released until April, seeing a prototype under glass, or just getting a sense of whether a company has their act together—even if it’s just two guys in a garage—nothing beats being there in person. My media pass to CES gets me access to a bunch of digital material and focuses it under a journalistic microscope—but most of this will be on the Web by the end of the week. Mostly, I’ll be curating and filtering that firehose of data, but I probably won’t see much more about each gadget than you can. The value I can provide as a reviewer won’t really come into play until some of these companies send me samples—which is unlikely in the case of a $45,000 electric SUV.

So I’m in the position of having to come up with a new definition of “eye-catching” to determine what to share with you. In one area that’s not a break with tradition, there were shows before the official launch of the conference where I saw a few things that covered the spectrum from infrared to ultraviolet—literally.

OWC Docks and Drives

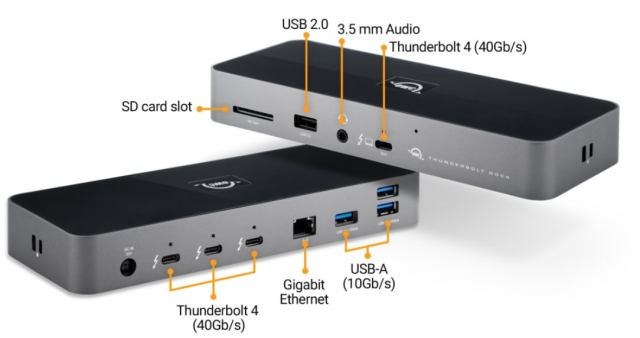

Other World Computing traditionally provides a suite at the Venetian that is an oasis of calm at CES, and the company has a reliable track record of solid products worth covering. A refreshed Thunderbolt Dock supporting the M1-based Macs’ Thunderbolt 4 is shipping this month, with the key improvement over last year’s Thunderbolt 3 dock being that Thunderbolt 4 supports hubbing one incoming and three outgoing Thunderbolt 4 ports (Thunderbolt 3 only allows for one port in, one port out). As usual, the Thunderbolt 4 ports double as USB-C. They are joined by gigabit Ethernet and three USB-A ports on the back, while the front sports one of the four Thunderbolt 4 ports, a 3.5 mm audio jack, a USB-A jack at USB 2.0 speeds (presumably for keyboards or charging), and an SD card slot. It sells for $249, a $50 reduction from the release price of last year’s Thunderbolt 3 dock. OWC has also refreshed its USB-C Travel Dock: the new USB-C Travel Dock E has added gigabit Ethernet to last year’s collection of one USB-C port, two USB-A ports, an SD card slot, and HDMI supporting 4K resolution. It’s available in February for $64.99. I think it’s attractive, and last year’s model was sturdy, but you can find docks with more features at this price point.

OWC’s new U2 Shuttle is a storage device designed to be slotted into a RAID or other multiple-drive bay, but the U2 Shuttle itself is also a multi-drive mechanism containing up to four NVMe M.2 SSDs. Users can address each SSD individually or use a RAID utility such as OWC’s SoftRAID (not included) to combine them into one logical device with a theoretical top speed of 64 GB/sec. Available now, a bare U2 Shuttle where you provide your own drives costs $149; U2 Shuttles with OWC storage start at $339 for 1 TB and $449 for 2 TB, up to $5299 for 32 TB.

1MORE ComfoBuds Pro Earbuds

1MORE reliably shows up at CES with an intriguing but sometimes bewildering line of audio products, many of which aim for the sweet spot of “pretty darned good for a mid-tier price.” For example, I have a review unit of last year’s Stylish earbuds ($79), and they’re the cheapest earbuds I’ve seen that can use either bud for master audio, allowing one to be used while the other charges in the case. But the sound quality and mic, while mostly decent, pale compared to other earbuds, and this year 1MORE is setting higher sights, squarely targeting AirPods. Its ComfoBuds look like AirPods with a rubber tip added, and the spec sheet makes them sound competitive: add IPX5 waterproofing, subtract an hour of playtime (4 hours vs. AirPods’ 5 hours), then wrap it up in a $59.99 price tag, on sale for $49.99 at the moment. The ComfoBuds Pro add “environmental noise cancellation (ENC)” and raise the price to $99.99. I wish I knew the difference between ENC and ANC. As I said, bewildering, partially because the materials I have don’t clarify between the ComfoBuds product line and the specific ComfoBuds product. I hope to have more detail when I can try a review model. ComfoBuds are available now, with ComfoBuds Pro coming in February.

Flic 2 Smart Button

The Flic 2 is a programmable button you can stick to things. That’s all. This struck me as silly until I realized how often I use my Philips Hue remote to turn on my lights. Flic 2 ties into Apple’s HomeKit (and a dozen other smart ecosystems such as IFTTT) to provide tactile access to any command, which might otherwise require 30 seconds of fiddling with your phone or remembering Siri’s magic word combinations. Buttons can be programmed with different results for press, double-press, and long-press.

Flic retailing is confusing. In US retail stores that the company is still lining up, a starter kit including the required hub, four buttons, and nine stickers with various icons for labeling the buttons is $159.99; additional buttons come in two-packs for $49.99. On Flic’s website, the starter kit has only three buttons for the same price, but there’s also a Pro Kit (six buttons, $219.99) and a Mega Kit (15 buttons, $399.99). Accessories include a $19.99 infrared beamer that enables a Flic 2 button to control any device that uses an IR remote control, a $3.99 metal clip to attach a Flic 2 to clothes or straps, and an additional 40-icon sticker pack for $4.99. It’s all available now online.

iHome PowerUVC Disinfectant Clock

iHome has a knack for coming up with designs that look reminiscent of Apple, so it’s not too surprising that its PowerUVC Pro alarm clock resembles the love child of an LED watch and a Mac mini. With the top closed, it functions as a standard bedside alarm clock. Flip the top lid open, and there’s a compartment that will sterilize your phone, keychain, and other handheld devices in 3 minutes using UV light. Use the built-in buzzer as an alarm or make the clock into a Bluetooth speaker; you can keep your phone charged with the two included USB charging ports. A quick search suggests that, although there are potentially infectious bacteria on mobile phones, the level is similar to frequently touched surfaces in domestic and public environments. The concern is higher for healthcare workers, whose phones carry a more worrying collection of pathogens. I’m not aware of the clinical value of disinfecting a phone, but I’m guessing it couldn’t hurt—but whether that’s worth $99–$129 (depending upon retailer) is a judgment call. Available now.

Pictar Stay Home Kits

Pictar sells a range of products designed to augment your phone’s camera; for example, its Pro Grip gives an iPhone the heft and physical feel of a camera body. Its new products for 2021 are an uninteresting line of selfie sticks, but I was rather impressed by its marketing of “Stay Home Kits,” each of which bundles a selection of products for a particular use. For example, its Family Zoom Kit includes a wide lens, light, and phone tripod for $109.99 ($15 cheaper than a la carte), while the Home Studio Pro Kit adds the Pro Grip to that bundle and costs $234.99 ($40 cheaper). I’ve been in innumerable Zoom calls where people were crowding around a laptop; had I known about the Family Zoom Kit a few weeks ago, I might have put one under a tree or two.

Ohmni Telepresence Robot

Robots have been ubiquitous at CES for a long time, so much so that it’s one reason the show is a comedic target. So there’s nothing new about a robot that’s basically an iPad on a high-tech stick—but I suspect many people have newfound uses for a Zoom-enabled tablet that they could navigate around a family member’s home that weren’t obvious a year ago. The $2699 Ohmni telepresence robot has an adjustable height that maxes out at 5 feet and a tilting neck that simulates head movements, and it includes dual cameras and a long-range mic and speaker. The company claims “quiet and smooth motion on any surface” (which I doubt applies to, for instance, beaches)—see the video. After the 5–6 hour battery runs out, there’s an autodocking system that starts the Ohmni recharging without anyone there having to fiddle with it. This model is the twelfth generation Ohmni has made, but it’s not new for 2021; if I see newer competitive gadgets that top it, I’ll write them up too. There’s a three-week lead time for delivery because each one is built to order based on customer preferences for various options.

WOWCube Gaming Device

WOWCube is a game that looks like it was dropped from the future. It’s a 2-by-2 Rubik’s Cube where each of the 24 squares is an independent screen, and each of the 8 smaller cubes that combine into a WOWCube is an independent module. Games on the WOWCube are three-dimensional; there may be things going on on all six surfaces. As with a Rubik’s Cube, you play games by twisting the sides or sometimes giving the whole thing a shake. A prolonged shake, similar to an Etch-a-Sketch, takes you back to the home screen where you can select a new game—again, watch the video. The WOWCube connects via your phone to the Internet, where the company plans to make available an ecosystem of game updates and new games. CubiOs says it will announce pricing and availability this week during CES.

Atari VCS Console and Ecosystem

Atari is back, and it immediately captured my middle-aged heart by demoing the new Atari VCS, which looks like an Atari 2600 that’s been baked in an oven with Shrinky Dink results. As you might expect, the Atari VCS ships with the Atari VCS Vault, a collection of 100 games that ran on the 1970s console, but it can also run modern games that you can purchase and download through an online store. The standard bundle includes an old-school joystick jazzed up with LED lights and a rumbler, along with a more modern controller. The Atari VCS Vault, store, and other apps like Chrome are all available in an ecosystem interface available on boot, similar to what Microsoft and Sony provide on their Xbox and PlayStation consoles. Atari also stole an idea from ColecoVision, enabling the Atari VCS to boot into Windows or Linux. As much as I want Atari to succeed for nostalgic reasons, I have trouble seeing this $389 product competing against the juggernauts of the Xbox Series S ($299) and PlayStation PS5 Digital Edition ($399, if you can find one). It strikes me as a product that will require oodles of venture capital and a loss-leader strategy to acquire sufficient market share to make developers take notice.

CES 2021 Gadget Survey #1

As always, the gadgets and gizmos at CES vary wildly in price and availability. But let’s have some fun. Assume price is no object. Would you actually use the products described above in everyday life? Register your vote in our quick survey. We’ll do this for each of our CES 2021 articles, and at the end, we’ll see which of the devices we’ve covered are most interesting to TidBITS readers.

Apple Unveils Stringent Disclosure and Opt-in Privacy Requirements for Apps

In late 2020, Apple rolled out its new privacy guidelines for apps, which require explicit and detailed disclosure by apps of their collection and use of personal data. In the near future, it will also require that apps get opt-in permission to track users by any personal identifier or a device’s unique advertiser identifier.

These two changes have roiled the online advertising industry, which has unfortunately shifted over its 25 years in existence from being excited about counting clickthroughs and measuring them against actions to luring users into a deliberately invasive stew of misdirection and obfuscation. By and large, the industry prefers that people don’t know how much their private information is being extracted and used, and it hates having to ask for permission—because it knows most people will say no.

The online advertising industry claims that advertising success is possible only through highly targeted advertising, in which each ad that appears on your screen is the result of a billion billion calculations of everything known about you, including your clicks and visits from mere moments ago. While that claim about success may or may not be true—an increasing amount of evidence, noted below, suggests that it is not—the industry has become dependent on concealing what it does with our information, fearful that if it were known, the house of cards would come crashing down.

This blog post from Invoca—a company whose business I cannot figure out exactly because the ad and marketing industry has become so very baroque—explains the insider view of Apple’s moves. The headline reads, “What Is IDFA and Why Apple Killed It.” IDFA is the device-based advertising identifier Apple attaches to its hardware, which functions like a browser cookie for a device and which users can reset whenever they like. However, when you dig into the post, it turns out that, despite the hyperbolic headline, the author actually says:

Apple hasn’t ‘killed’ IDFA per se, but has made tracking in apps an ‘opt-in’ situation in iOS 14 as part of the company’s continued focus on user privacy.

In other words, Apple is blowing like mad on that house of cards.

Among the top tier of tech companies, Apple is the only one that places its customers’ privacy in its list of central concerns—and means it. Other big firms flap their gums about how privacy is important, then routinely lobby for loopholes, pay small fines for violating regulations, or construct methods that deceptively violate user consent.

While Amazon and Google have their own issues with disclosure, tracking, and consumer violations in the US and internationally, the biggest privacy abuser is, of course, Facebook. Facebook’s business model appears to rely on routinely violating its users’ privacy and then promising to do better, which it never does.

Apple has progressively clamped down on user tracking in Safari and apps over the last few years, describing such efforts as part of its mission to create a safe and generally “opt-in” Internet, in which your online activities remain protected and private unless you choose otherwise. Apple’s new app-based disclosures and the requirement of consent to track outside of the app continue its evolution in insisting on customer privacy.

Signs are already visible that the whole edifice of the online ad industry may be due for a collapse. So much of the money collected ostensibly on behalf of publishers is sucked up by ad tech firms, ad fraud, and intermediaries that half or less reaches the actual sites. Some research suggests it’s as little as 30 cents on the dollar.

Other examples of a possible adpocalypse?

- JPMorganChase reduced its advertising reach from 400,000 sites to 5000 and saw no change in outcome.

- Uber audited its ad spending to generate new users and went from $150 million to $20 million in spending without a drop in actual leads.

- Proctor & Gamble slashed $200 million in online spending and found its reach increased.

- eBay cut $100 million in ad spending without a drop in referred sales.

For instance, try to explain why, after you purchase a given item, ads for that same item chase you around the Internet. Ad efficiency? Hardly.

Apple’s privacy moves might topple some dark ad giants who don’t deliver for advertisers (or publishers) and have managed to hide their incompetence behind Rube Goldberg contraptions. It’s not unthinkable that Apple could help sweep in a simpler, more direct, and less intrusive advertising that resembles the Internet’s earlier days.

That’s probably too optimistic, but let’s start with the changes Apple has already made and the opt-in requirement on third-party tracking about to emerge.

From a Single Line to Pages of Revelations

Apple’s new disclosure requirements are relatively easy to understand and summarize. Apps must disclose what data they may collect, and whether that data is linked to users, stored outside the app, or used to track them. In terms of simplicity, it’s fair to compare them to the nutrition facts label on packaged foods, thanks to the standardized format and language. But, just like those labels, it’s worth noting that the data is self-reported. Apple’s role in monitoring and verification is unclear, and there are a variety of exceptions.

Developers who have conformed to Apple’s privacy rules in the past, to the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (as of May 2018), and to the California Consumer Privacy Act (in effect from January 2020) should already have gathered all of this information and provided it in one or more policies within the app and on a website. That should be effectively all developers, even one-person firms, because of the broad scope of those existing laws, rules, and Apple guidelines.

What Apple calls “app privacy details” systematizes and makes simple all the kinds of data about you that an app collects, including via embedded third-party code, and how the developer handles it. Instead of reading a lengthy privacy policy that could be written to any standard, Apple’s details use standardized terms and top-level icons. (The GDPR nominally requires language in privacy disclosures that’s plain and easy to read, but it provides no assistance in doing that, nor does it seem to enforce the prohibition on confusing language.)

Apple offers developers an equally straightforward description of how to collect and provide all the necessary information. The general principle is that any data that’s collected or inferred by an app and sent off-device for “a period longer than what is necessary to service the transmitted request in real time” must be disclosed. For instance, someone might provide their email address to an app for it to retrieve some piece of information, but if the app’s developers and any connected third parties immediately dump that email address after the retrieval, it doesn’t seem to qualify as “collected” in Apple’s definition. (Please note that I am not a lawyer, and this article doesn’t constitute legal advice.)

The app privacy description covers which categories of data might be collected, providing specific examples for each (such as location, financial, contact information, and the like), how it’s linked to the user (and how to avoid such linkages), and how an app developer or affiliated third party might track a user based on collected data.

Apple also makes it clear that there’s a big difference between on-device and off-device tracking, personalization, and data usage. An app can download and cache marketing information, including from third parties, and then apply personalization or other behavior within the app based on locally stored personal information and the advertiser identifier. As long as that information isn’t then sent off the device, it doesn’t have to be disclosed. (This principle is similar to how Apple has allowed companies to provide phone-number spam identification, by allowing databases of numbers to be downloaded to an app and then compared only locally against incoming phone numbers.)

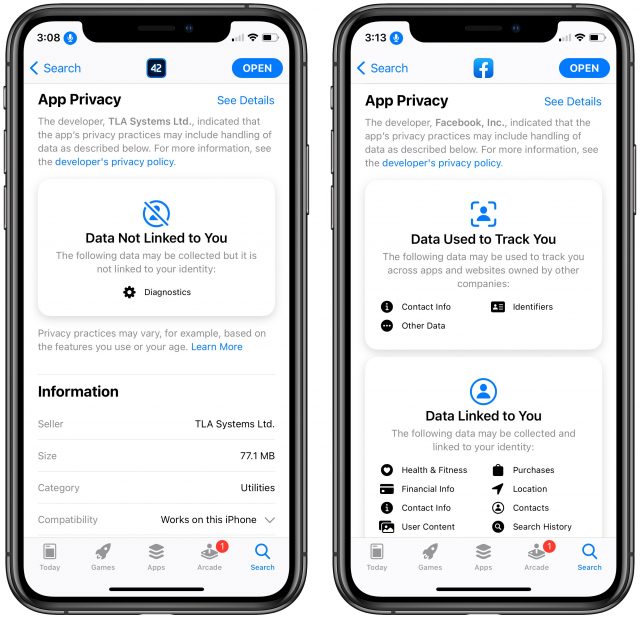

These privacy details are presented in Apple’s various App Stores in an App Privacy panel below version history. Under Data Linked to You, it specifies all the categories of data, with distinct icons, that are being used. There may also be a Data Not Linked to You section that discloses (sometimes optionally) data that’s collected either only on-device or for diagnostic purposes, or that is not retained after a lookup or retrieval. Tapping or clicking See Details provides a more thorough item-by-item accounting.

The range of disclosure can be mind-bending. James Thomson’s popular calculator app, PCalc, collects diagnostic data that’s not linked to the user in any way; it gathers nothing else. Facebook’s disclosure, on the other hand, runs to ten iPhone screens.

Apple, by the way, does not require that app developers disclose information that Apple itself collects through the use of Apple frameworks and systems, like advertising or in-app purchases. Apple already has agreements as a “first party” with the user of an app in order to use an iPhone, Mac, or other device. It has disclosed terms and required acceptance of licenses and data-collection policies as part of a user setting up a device and signing into a given App Store on it. Those terms and agreements may not be as clearly displayed or worded as would be ideal, but we can hope that Apple will be working to improve that user experience as well. (Apple lets you opt out of some of its tracking and collection, too, as I detail at length in my book Take Control of iOS & iPadOS Privacy and Security.)

Apple’s apps, however, do have their own App Privacy listings. Pages notes that it might link “Contact Info, User Content, Identifiers, Usage Data, and Diagnostics” to you. That seems like an awful lot of linkage for a word-processing app. However, when you click See Details, Apple clarifies that it uses most of the data for analytics (measuring usage and what people do), while only using a few pieces of information for customizing the app, and that it has access within the app to user content (photos, video, data, and other documents).

As always, the question is whether disclosure prompts changes by individuals. The App Privacy listing is just a disclosure: users can’t opt in or out of different kinds of data collection—it’s all or nothing. But unlike a standard software EULA (end-user license agreement) or dense privacy policy, Apple’s requirements and presentation make it quite clear what’s up, assuming the developer has been truthful, of course. Then you take it or leave it: you either buy or install the app or don’t.

However, Apple is about to enable an option that will give you choice over one set of items disclosed in App Privacy. Sometime soon—the company hasn’t yet said when—Apple will require that you opt into third-party tracking. That’s what has Facebook quaking, and what I’ll explain next.

The Holy Grail of Permission-Based Marketing and Advertising

What could have terrified Facebook enough about Apple’s upcoming App Tracking Transparency requirement that it took out a full-page ad in multiple newspapers and created an accompanying website alleging that Apple’s update would endanger small businesses? It’s this little message, as Tim Cook noted on 17 December 2020 in a tweet (see “App Store Wars: Facebook vs. Apple, Publishers vs. Apple, Apple vs. Brave,” 17 December 2020).

We believe users should have the choice over the data that is being collected about them and how it’s used. Facebook can continue to track users across apps and websites as before, App Tracking Transparency in iOS 14 will just require that they ask for your permission first. pic.twitter.com/UnnAONZ61I

— Tim Cook (@tim_cook) December 17, 2020

Facebook characterizes this message on its advocacy site thusly: “Apple’s new iOS14 [sic] policy requires apps to show a discouraging prompt that will prohibit collecting and sharing information that’s essential for personalized advertising.”

To paraphrase: Facebook’s entire advertising model is so fragile that if users were given the information to choose between having their information shared willy-nilly and relying on Facebook to preserve their privacy, advertising results would collapse. That would be a damning admission, no?

Even some Facebook employees thought Facebook’s stance was a bunch of hooey, according to Buzzfeed News. “It feels like we are trying to justify doing a bad thing by hiding behind people with a sympathetic message,” one engineer wrote. Another worker reasonably asked, “Why can’t we make opt-in so compelling that people agree to do so[?]”

Facebook won’t be the only company whose apps will trigger this new transparency alert, of course. All apps that send information Apple defines as providing a way to track a user outside that developer’s “first-party” ecosystem will have to present and honor a similar dialog. For some apps, that might be just the app; for others, the app and servers or other resources organized under an associated domain. For still others, it could be broader and encompass a range of networked hardware and services.

In other words, Facebook doesn’t need to display such an alert to share tracking identifiers from the Facebook app on an iPhone with the Facebook website someone might access from a browser on a Mac. But after passing data to and from the Facebook website, the company can’t pass any tracking identifiers to other parties. To make its targeted ad approach work, Facebook—or any company that shares information with data brokers—would have to display the tracking prompt. (Apps can also share and use certain identifying information to deter or detect fraud and for security purposes.)

But there is a red line: if a company shares information that can track a user outside of stuff it owns or operates on its own behalf, this transparency requirement is triggered. How Apple will enforce that, for companies with expansive services, remains to unfold. Can Facebook track across its Instagram and WhatsApp subsidiaries without an alert?

This tracking prompt will appear the first time you launch an app after Apple enables App Tracking Transparency. If you later change your mind, you can make modifications in Settings > Privacy > Tracking. Apps can explain why the pop-up appears, or they can rely on a generic message. (This approach is very similar to Location privacy, which Apple has tightened over multiple releases of iOS and iPadOS in response to developers and ad networks creating workarounds and exploiting loopholes.)

Notably, apps cannot require you to opt into third-party tracking in order to use the app. As Apple notes in its developer FAQ: “[Q] Can I gate functionality on agreeing to allow tracking, or incentivize users to agree to allow tracking in the app tracking transparency prompt? [A] No…”

The Electronic Frontier Foundation argues that Facebook’s campaign against Apple has nothing to do with users or small businesses. Instead, the EFF suggests, Facebook is attempting to shore up a business model that relies on abusing privacy and to distract from its anti-competitive behavior.

But the EFF’s primary, seemingly obvious stance resonates even louder:

We shouldn’t allow companies to violate our fundamental human rights, even if it’s better for their bottom line.

Blow on that house of cards, Apple, blow.

Apple Isn’t in the Business of Treating Its Customers Like the Product

Critics and cynics will note that Apple doesn’t have to play nice with advertising networks because only a minuscule portion of its massive revenue stream comes from ads. Such people might suggest that deploying restrictions that could reduce ad revenue to Amazon, Facebook, Google, and even Microsoft, would hamper their efforts to challenge Apple’s hardware ecosystem or develop competing apps and services. (You may not think of Microsoft as being focused on advertising, but the company generated a surprising nearly $8 billion in ad revenue in its 2020 fiscal year.)

But it’s hard to see Apple needing to resort to using privacy as a weapon to hurt other tech giants. Amazon makes its money selling all kinds of stuff, and even its hardware that does go head-to-head with a few Apple products—the Echo smart speakers and Fire TV—is up against the HomePod and Apple TV, which are perhaps Apple’s lowest-selling hardware products. Google’s Android operating system derives revenue from advertising, and a recent filing from the US Department of Justice states that Google pays Apple $8 to $12 billion a year to be the default search engine on Apple devices. Microsoft exited the mobile business, and despite the scale of Windows, the company has refocused its efforts into making its apps and services available on every platform, including Apple’s. Privacy may be a selling point for Apple, but overall, the company isn’t using it as a competitive cudgel against other companies.

Tim Cook’s consistent, principled stance in nearly all aspects of user privacy—including apologizing and making changes when flaws or exceptions are discovered—can be both sincere and a marketing tactic. But just like, say, Walmart’s move towards renewable power and reduced emissions, we can accept the benefit to society while keeping a gimlet eye poised to watch for failures or misleading statements.

In the end, there’s nothing wrong with Apple’s efforts to reduce the amount of undisclosed, unwanted, and opt-out forms of tracking across the Internet, even if they end up puncturing the cash balloons of parasitic data brokers, intermediaries, and ad tech firms.