#1684: OS bug fix releases, Finder tag poll results, Messages identity verification, blocking spambots, which Apple services do you use?

Apple updated many of its operating systems last week, not primarily for security vulnerabilities, but to fix some gnarly bugs. Glenn Fleishman dives into Contact Key Verification, a tweaky feature in the next version of Messages that helps anyone who’s a high-value target avoid falling prey to a compromised conversation. We report on the results of our poll about Finder tag usage and share a look behind the curtain at some of the server-side issues that have occupied our time of late. Finally, this week’s Do You Use It? poll asks which—if any—of Apple’s marquee subscription services you pay for and use. Notable Mac app releases this week include Retrobatch 2.0, Keyboard Maestro 11.0.1, BusyCal 2023.4.4, GarageBand 10.4.9, Lunar 6.4.2, ChronoSync 11 and ChronoAgent 11, and Logic Pro 10.8. ![]()

LittleBITS: Email Delivery Problem and Blocking Spambot Accounts

Those who create and maintain online services seldom talk about just how hard it can be to keep everything working, but the reality is that websites and other Internet-based services require significant tending. We’ve had several incidents of late that you may have noticed.

TidBITS#1683 Email Issue Delivery Problem

Last week’s email issue of TidBITS#1683 suffered a delivery problem we haven’t been able to solve or reproduce. After sending to about 19,000 people, Sendy, the app that manages outgoing email messages based on addresses from our WordPress server, started receiving 403 or 503 errors when passing individual messages on to Amazon’s Simple Email Service (SES) for delivery. We could find nothing wrong at Amazon SES and nothing amiss with the remaining 5,500 addresses. Subsequent sends of individual articles to TidBITS members and of our Dutch and Japanese translations worked fine. After nearly a week, we had nothing more to try, so we canceled the remaining sends of TidBITS#1683 to prevent Sendy from filling the drive with error logs.

The upshot is that if you didn’t receive last week’s email issue, my apologies! You can read TidBITS#1683 on our website, along with all other back issues. I sincerely hope everything works better for TidBITS#1684 because nothing changed before the last issue, and we haven’t changed anything since. We plan to install an update to Sendy soon, but since we’ve never had a problem before, it’s hard to imagine it will fix whatever cosmic ray caused problems for last week’s issue.

Email Verification for New Accounts

A few months ago, we deployed email verification for new accounts. For years, we had been fighting a losing battle against spambots that created thousands of fake accounts in our WordPress system. I don’t know why they do this since these accounts have no significant capabilities. I suspect we were just among the random victims of roving spambots that detected a WordPress server.

Spambots can do this because WordPress, by default, lets potential users create accounts instantly. We had various forms of security in place—the Stop Spammers plug-in, non-standard URLs, reCAPTCHA, and more—but nothing stopped or even really slowed the spambots. And to be clear, it was terrible. At the peak, the spambots were creating hundreds of accounts daily. Even identifying the few legitimate accounts while deleting the fake ones was difficult.

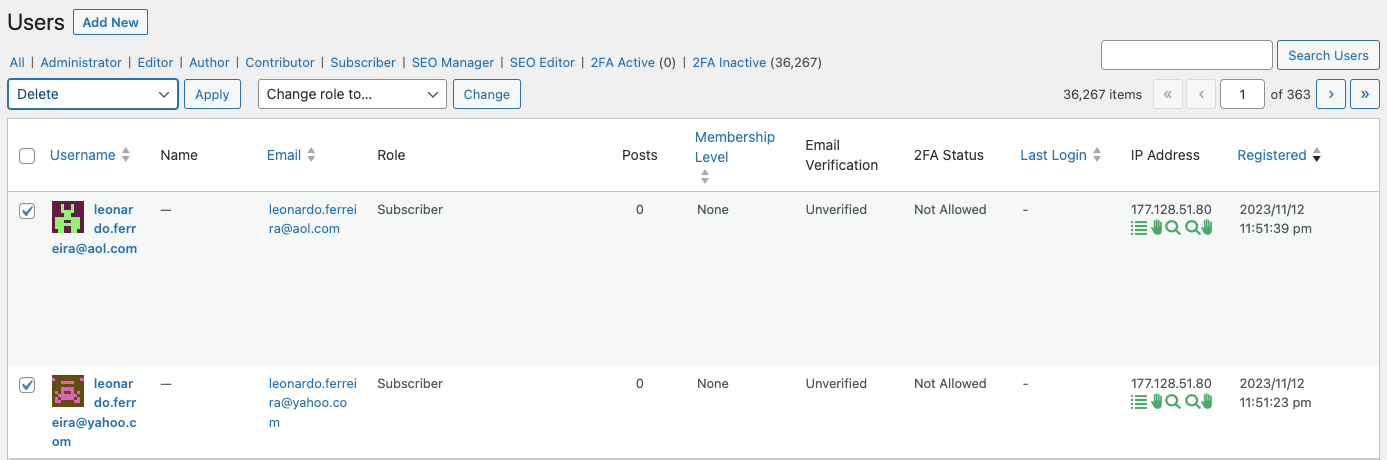

Eventually, we installed the User Verification WordPress plug-in. It doesn’t prevent spambots from creating accounts, but new accounts are marked as Unverified until the user clicks a link in an email confirmation message. Although it’s conceivable that a spambot could subscribe a compromised email address and then click the link in the received confirmation message, most don’t. I hoped that, after we had marked all our existing users as Verified and become comfortable with User Verification, we could enable its option to automatically delete accounts that remained Unverified after some amount of time.

Alas, it was not to be. For reasons we never figured out, when I turned on that feature, it deleted 17 accounts marked as Verified and connected with actual people. I can’t trust it not to delete accounts again, so I’ve fallen back on deleting spambot accounts manually.

What I really want is a system that emails a token-secured link to someone who submits their email address in a subscription form but doesn’t create the account until the user manually clicks that link. That’s not something I’ve been able to find in the WordPress plug-in world, and our developer doesn’t have time to build such a system right now. Suggestions welcome.

Being able to see which accounts remained marked as Unverified simplified the process of deleting the spambot accounts a little, and while I was doing that, I noticed some commonality among the IP addresses associated with the spambot accounts. (Stop Spammers displays the source IP address in the WordPress user list.) When I looked them up, I discovered many were controlled by a Russian ISP called Biterika Group. Although Scamalytics currently considers Biterika Group a low fraud risk, at the time, it was definitely responsible for the spambots attacking my server. My efforts to block particular domains and Russia as a country using Stop Spammers had little effect, making me so frustrated and angry that I decided to go nuclear and block entire IP address ranges. That’s generally a bad idea because it can affect legitimate users and because the list is difficult to manage. But, Russia, so whatever.

(As an aside, the trick to blocking many of the 46,000 IP addresses controlled by Biterika was CIDR notation. CIDR is short for Classless Inter-Domain Routing and is an IP addressing scheme that allows a single IP address to designate many unique IP addresses with CIDR. A CIDR IP address looks like a regular IP address with a trailing slash, followed by a number called the IP network prefix. For instance, some of the Biterika IP addresses were around 109.248.204.0, and adding 109.248.204.0/23 to my Stop Spammers blocklist prevented spambots from that IP range from doing anything on my site. I use this CIDR to IPV4 calculator to determine the appropriate IP network prefix to use.)

Blocking all the Biterika IP addresses was so successful that I started checking IP addresses on any spambot accounts and adding them to the blocklist if they weren’t from an English-, Dutch-, or Japanese-speaking country. I fully realize the implications of this, and if any TidBITS reader who has been blocked contacts me via email, I’ll remove the offending IP address range.

The combination of requiring users to click a link in a confirmation message and blocking spambot IP addresses has been highly effective. A few spambot accounts sneak through, but I can deal with a handful a week compared to hundreds per day.

From the user perspective, we’ve had some hiccups along the way, and I’m hugely appreciative of Lauri Reinhardt’s assistance in helping users and teasing out unexpected quirks and Eli Van Zoeren’s tech work in installing and configuring everything. It took us a while to configure the email verification options correctly, fix conflicts caused by multiple plug-ins providing CAPTCHA checking, eliminate broken Register buttons deep within the site, figure out the interaction between the TidBITS and TidBITS Talk sites (which share a login system), and work through various edge cases. Even now, we worry that there’s a bug in User Verification that causes some accounts to be marked as Unverified after a manual membership renewal, but we haven’t been able to track that down.

Existing users should be largely unaffected by these changes, but if you run into any problems using our sites, please let us know at [email protected]. We want everything to work!

Apple Squashes Bugs with iOS 17.1.1, iPadOS 17.1.1, macOS 14.1.1, macOS 13.6.2, watchOS 10.1.1, and HomePod Software 17.1.1

Apple has pushed out updates to all its current operating systems (and macOS 13 Ventura) except for tvOS. They’re designed to fix a handful of problematic bugs related to updating, battery life, and Siri reliability, though they may also address security vulnerabilities that Apple discovered on its own—there are no published CVE entries.

iOS 17.1.1 and iPadOS 17.1.1

iOS 17.1.1 addresses two bugs, and iPadOS 17.1.1 piggybacks on one of those fixes. First, Apple says that Apple Pay and other NFC features may become unavailable on iPhone 15 models after wireless charging in certain cars—MacRumors says it was BMW. Second, Apple’s engineers got their act together just in time to fix the Weather Lock Screen widget, which didn’t always correctly display snow. 🌨️

Unless you use wireless charging in your car and rely on Apple Pay, I recommend waiting to install these updates until it’s convenient.

macOS 13.6.2 Ventura

The release notes for macOS 13.6.2 say it “provides important bug fixes and is recommended for all users,” but that doesn’t seem entirely accurate. Apple’s Security Releases page lists macOS 13.6.2 as applying only to the “MacBook Pro (2021 and later) and iMac (2023).” So it’s not recommended for all users, and indeed, my 2020 27-inch iMac isn’t even being offered the update.

However, Mr. Macintosh deserves kudos for discovering in Apple’s Enterprise release notes for Ventura that macOS 13.6.2 also fixes a bug that could cause 14-inch and 16-inch MacBook Pros with Apple silicon to start up to a black screen or circled exclamation point after the built-in display’s default refresh rate was changed.

Plus, although I don’t know where he got the information, Howard Oakley writes that macOS 13.62 addresses two update-related problems:

- MacBook Pro models with Apple silicon could have problems while updating to macOS 13.6.1 that result in a black screen failure mode.

- Some just-released M3 24-inch iMacs shipped with macOS 13 Ventura installed instead of macOS 14 Sonoma. That’s an embarrassing misstep on Apple’s part, but worse is the fact that they couldn’t be updated or upgraded using existing updates.

There’s no need to install macOS 13.6.2 unless you plan to update a MacBook Pro with Apple silicon to macOS 13.6.1 or have just purchased an M3 iMac that came with Ventura. If it were me, I’d install this one just to get it out of the way.

macOS 14.1.1 Sonoma

Apple says only that macOS 14.1.1 “provides important bug fixes and security updates and is recommended for all users.” Given what Howard Oakley says about the M3 iMacs, I suspect that macOS 14.1.1 is designed to allow those users to upgrade to Sonoma.

Craig Hockenberry also reports that macOS 14.1.1 addresses a macOS 14.1 window server bug that affected tools in his xScope app and—probably more what triggered Apple’s quick fix—Photoshop.

There’s no telling how many apps would be affected by this bug, so I encourage updating soon, particularly if you notice any unusual behavior with graphics apps.

watchOS 10.1.1

Nearly every iOS or watchOS update generates squawks from some users about reduced battery life. Usually, those issues resolve quickly as the operating system finishes building caches and indexes. Sometimes, there are actual bugs, though, which seems to have been the case here since watchOS 10.1.1 “addresses an issue that could cause the battery to drain more quickly for some users.”

I’ll be installing this one right away. Unsurprisingly, my new Apple Watch Series 9 has had stellar battery life since I got it, but it nearly ran out of power on my bike ride yesterday. Perhaps I failed to put it on the charger properly the night before, but any time Apple says an update should prevent unnecessary battery drain, I mash the Install button.

HomePod Software 17.1.1

During the pandemic, I installed a lot of HomeKit switches, so we’re accustomed to controlling lights in our house using Siri on an original HomePod (see “Reflections on a Year with HomeKit,” 17 December 2021). When you talk to Siri every time you want to adjust the lightning, you get a feel for how well it’s working. (OK, I’ll admit, as much as I try to avoid it in my writing, we totally anthropomorphize Siri in everyday life, such as when Tonya exasperatedly exclaimed last night, “She’s being super dense today.”)

So yes, although we don’t have hard and fast statistics on it, our sense is that Siri’s reliability for executing common HomeKit commands suffered after the release of HomePod Software 17. Sometimes, we have to ask two or even three times before Siri will recognize the command. It’s not so bad that we instead walk over to the light switch and activate it manually, like an animal, but I’ll be pushing HomePod Software 17.1.1 to our HomePods right away, given that Apple says it “addresses an issue where some HomePod speakers could respond slowly or fail to complete requests.”

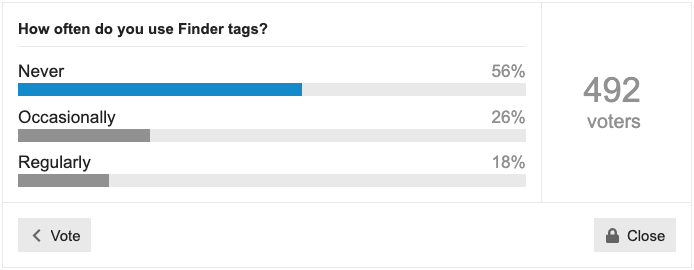

Do You Use It? Finder Tags See Focused Use

A few weeks ago, we asked how often you use Finder tags. I haven’t been a fan of Finder tags since they were introduced a decade ago in OS X 10.9 Mavericks, so I wasn’t surprised that 56% of respondents never use them. Another 26% use them occasionally, with 18% relying on them regularly. But perhaps we naysayers are missing out.

Basics of Finder Tags

The point of Finder tags is to provide an alternative way of organizing files and folders beyond the traditional folder hierarchy. A file can exist in only one folder (although you can make aliases), but a single file can have as many tags as you like, making it possible to bring together files scattered across your drive or even just a subset of files within a single extensive collection.

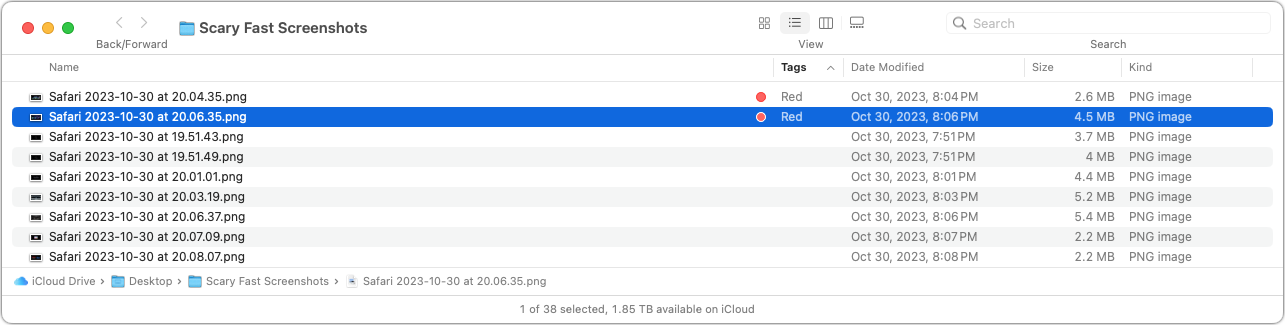

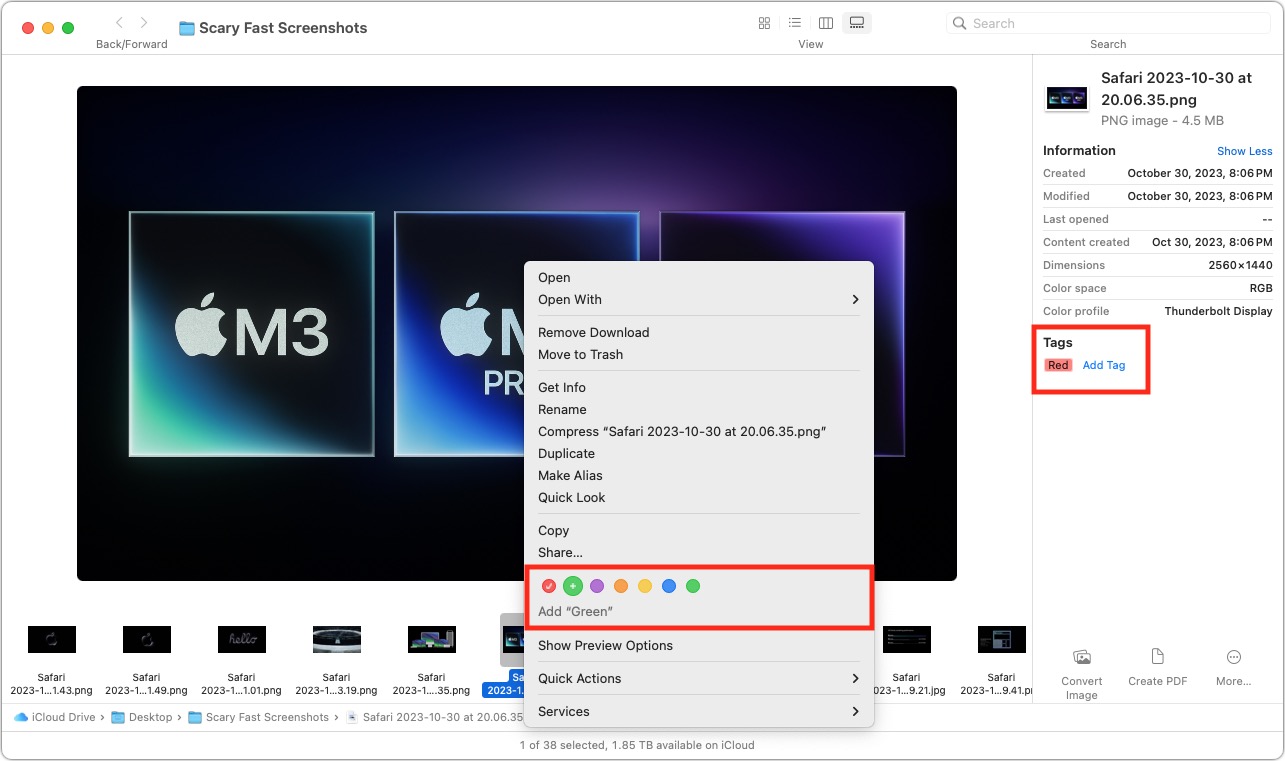

Imagine you have a folder containing a few hundred images and need to select a handful for use on a website. If you change your Finder window view to Gallery, you can spin through the images quickly, applying a tag to those you like by adding it from the info pane or Control-clicking the file and choosing a tag from the contextual menu. There are many other ways to apply tags, too.

Once you’re done, you can focus on just those files by adding a Tags column to a List view window (Control-click any of the column headers and select Tags) and then clicking it to sort by tags. Or you can put a tag in the Finder window’s sidebar by selecting its checkbox in Finder > Settings > Tags. There are plenty of other ways, too. After you’ve finished, you can remove the tags just as you added them.

Once you’re done, you can focus on just those files by adding a Tags column to a List view window (Control-click any of the column headers and select Tags) and then clicking it to sort by tags. Or you can put a tag in the Finder window’s sidebar by selecting its checkbox in Finder > Settings > Tags. There are plenty of other ways, too. After you’ve finished, you can remove the tags just as you added them.

For more details about using tags, see Josh Centers’s comprehensive article “All about Tagging in the Mavericks Finder” (14 November 2013). The details may have changed slightly in the last decade, but most of it still applies. Howard Oakley also wrote about Finder tags recently, and Jeff Carlson has a section on tags in Take Control of Managing Your Files.

Common Tagging Approaches

From the discussion following the poll, it became clear that tags are essential to the workflow for some people and teams. For instance, Gobit wrote:

Use them all the time at work (design studio and prepress operation for large printing company). Every job in its own folder, every folder on a server, every folder tagged by colour and initials. Column view. Makes it very easy to see who is/find by/group by person responsible for which of 600+ live jobs at any one time.

And Anton Rang said:

I have some thousands of technical papers and hundreds of standards documents on my Mac. By tagging the standards documents, I can easily limit a Spotlight search to just those, without the papers coming into play. I also use tags to a lesser extent to narrow down searches to particular standards families, or documents from a particular vendor, and sometimes for specific projects.

But far more common were those who used tags more casually. Common uses include:

- Tagging files temporarily to make them stand out in a folder

- Tagging in-progress files differently from those that have been completed

- Tagging important files that are needed regularly

- Tagging frequently used folders to collect them from around the drive

- Tagging files that can likely be deleted in a later pass

- Tagging document versions to separate the current one from previous versions

- Tagging files by client so they can be found across multiple drives

- Tagging related files that are spread throughout multiple folders

I encourage you to read the entire discussion to see more real-world ways people use tags.

Problems with Finder Tags

Some people have tried Finder tags but given up on them due to various problems:

- Too few colors: By default, the Finder provides seven tags named for their colors: Red, Orange, Yellow, Green, Blue, Purple, and Gray. (Alas, Roy G. Bpg doesn’t roll off the tongue like the rainbow color mnemonic Roy G. Biv.) You can rename the default tags—though there’s little reason to do so—but you can’t assign any other colors. Since a colored circle is the primary way of identifying tagged files in a Finder window, seven colors is unnecessarily limiting.

- Harder to see tagged files than it used to be: Numerous people mentioned that they found tags much less helpful since macOS stopped highlighting the entire file name with the tag color and moved to applying just the little colored circle. The main advantage of the circles is that it makes it easy to identify files with multiple tags.

- Tags don’t survive all transfer approaches: In testing under the current versions of Dropbox, Google Drive, and iCloud Drive, applying tags to files caused those files on another Mac logged into the same account to reflect the tags only when transferred via Dropbox or iCloud Drive. With Google Drive, tags seem to be restricted to the Mac on which they’re applied. Similarly, tagged files shared in other ways lose their tags unless the transfer approach supports metadata. Tags can appear on other devices, such as in the Files app on an iPad, but are not always consistent in services other than iCloud Drive.

- Collaborator’s tags can muddy your tag set: When you share a folder with someone using Dropbox (but not iCloud Drive, interestingly), any tags the other person applies to shared files will automatically be added to your collection of tags. The same goes for tagged files shared on a USB flash drive or other approach that maintains metadata. On the one hand, this makes sense for a team using tags as part of their collaboration workflow, but it also means that your tag collection may include a bunch of tags that come from others and are thus meaningless to you.

- Spotlight sometimes has problems: Although those who rely heavily on tags seem to have few troubles, others said they had experienced issues with Spotlight performance and finding tags reliably. Even if Spotlight is reliable nearly all the time, the worry of losing tags might prevent some people from venturing beyond safe organization techniques involving folders and file names.

Personally, I’ve come away with a renewed appreciation for how I might use Finder tags. I’ll never be a heavy user because I rely too much on Google Drive, which doesn’t preserve tags between my Macs, but I recently found it helpful to tag files I wanted to collect temporarily. Since this poll has brought tags back to the forefront of my mind, I’ll be considering whether other aspects of my workflow might be improved with the judicious use of tags. Hopefully, you’ll remember that tags are an option the next time you find yourself in a situation where they could be helpful.

Upcoming Contact Key Verification Feature Promises Secure Identity Verification for iMessage

Apple relies on increasingly outdated notions of end-to-end security for your messages with other people. While the company has regularly applied fixes to iMessage and its Messages apps to improve security and privacy, it hasn’t kept up with industry lessons and innovations. Apple is promising to change one key (sorry) component of that this year with an optional feature currently available in developer betas of iOS 17.2, iPadOS 17.2, macOS 14.2, and watchOS 10.2. The company announced the process and timeline on 27 October 2023 on its Security Research blog.

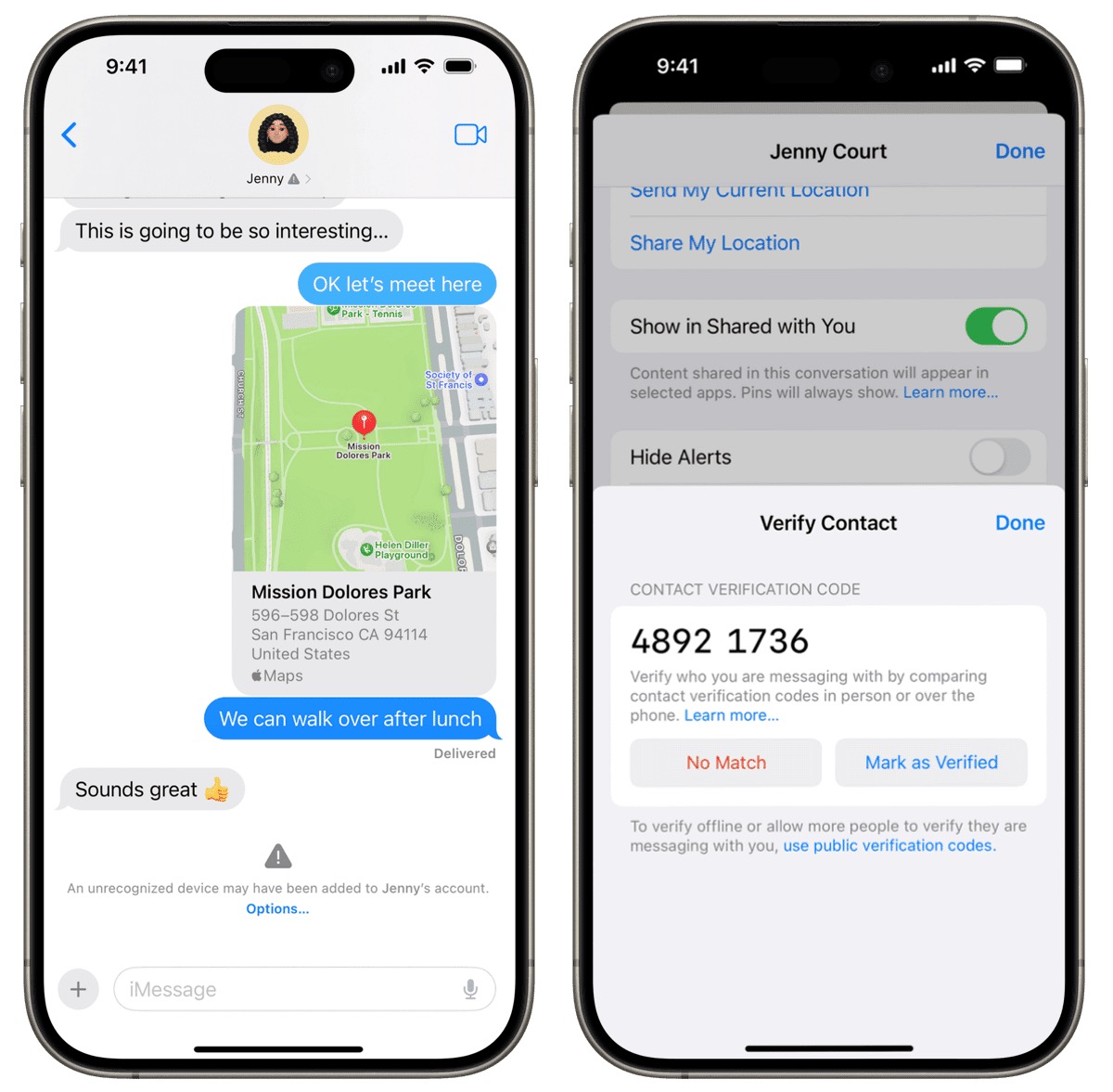

The feature is called Contact Key Verification, and its does just what its name says: it lets you add a manual verification step in an iMessage conversation to confirm that the other person is who their device says they are. (SMS conversations lack any reliable method for verification—sorry, green-bubble friends.) Instead of relying on Apple to verify the other person’s identity using information stored securely on Apple’s servers, you and the other party read a short verification code to each other, either in person or on a phone call. Once you’ve validated the conversation, your devices maintain a chain of trust in which neither you nor the other person has given any private encryption information to each other or Apple. If anything changes in the encryption keys each of you verified, the Messages app will notice and provide an alert or warning.

Apple’s post is written for the security community, so it references numerous complex cryptography concepts. Since Contact Key Verification is aimed at only those people who have significant reason to believe that hostile parties with significant resources want to compromise their communications, let me give you three levels of explanation: the first is just a quick overview, the next provides more details; and the last digs more deeply into the underpinnings.

To be clear, few people need this level of messaging security. If you’re a journalist, public figure, human-rights advocate, politician, well-known financier, or other likely target of thieves, governments, or tech-savvy stalkers, Contact Key Verification’s additional level of safety might seem like a godsend. The rest of us can decide if we care enough about the remote possibility of impersonation in an iMessage conversation to put up with the extra verification step.

Just the Facts

When you first started using iMessage within Messages, Apple had your device set up encryption, a public portion of which is shared with Apple, which stores it on your behalf. That public portion of the encryption setup helps Apple create a secure connection whenever you have a Messages chat with blue-bubble friends.

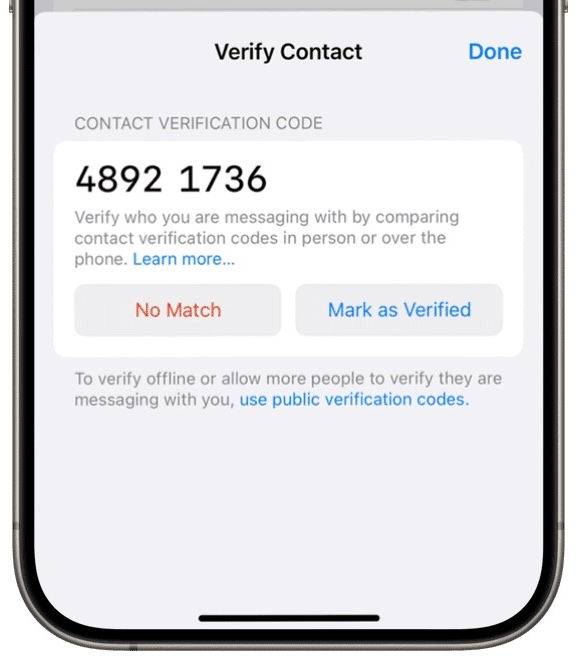

With Contact Key Verification, you go an extra mile to detect and prevent impersonation: you and the person with whom you’re communicating verify your identities in Messages. You do this by sharing a numeric code that lets you manually establish cryptographic trust between your accounts and devices.

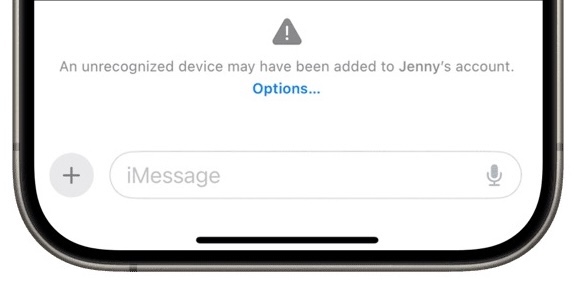

If anything breaks that cryptographic trust, the Messages app becomes aware of this—no involvement by Apple is necessary. Messages then notifies you, the other party, or both of you with a message that explains why, and it suggests actions you can take now that you can no longer trust the connection.

High-Level Tour of the Contact Key Verification Process

Let’s look at each step of how Contact Key Verification works in a little more detail.

- Currently, all iMessage conversations are secured end-to-end by having one of your devices initially create a public-private key pair. It retains, secures, and syncs the private key among your devices and shares the public key with Apple. Apple maintains the public key in a key directory service that enables it to connect iMessage participants.

- With Contact Key Verification, your devices generate another encryption key that’s only synced securely among your devices and not shared with Apple in any way. That new key is used to validate your previously provided public key through a process known as signing. Your device sends Apple the signed message, which reveals nothing of the original key. Apple now has your public key and a separate verifiable signature that can be used to verify whether the public key has changed in Apple’s key directory service.

- To use Contact Key Verification, Apple will let you and another party confirm a short numeric code with each other to verify each other’s identities in an iMessage conversation. (Other messaging apps, like Signal and WhatsApp, offer a similar verification option.)

- This verification step of confirming a numeric code is cryptographically strong because it doesn’t transmit any private information between you. Plus, Apple isn’t party to the verification process—it doesn’t involve Apple servers, mediation, or storage.

- However, Apple does play a role in verification. The company will continuously publish a cryptographically scrambled and anonymized list containing iMessage user public keys and the signed component that’s delivered whenever anyone enables Contact Key Verification. This list is generically called a transparency log. Apple has already started such a log, generating more than two billion entries per week! (Apple says in its blog post that WhatsApp has already launched a similar log.)

- When anyone who has opted into Contact Key Verification communicates with someone else using iMessage, both parties’ devices independently consult the public transparency log to ensure that neither the log nor the keys they exchanged have been compromised. During this process, the devices reveal nothing about their private or local encryption keys to Apple (or anyone else).

- Messages warns you when anything unusual or dangerous happens, such as another device being added to the other person’s account without proper validation, a key failing to match a previously verified one, or your contact using a key that’s outdated compared to the updated information on the transparency log.

As a practical example of what could happen, suppose some government intelligence agency has identified reporters, politicians, or others communicating over iMessage with human-rights advocates, spies, or other people. The agency’s goal is to impersonate the former parties to gain the trust of the latter and discover their location, the people with whom they communicate, and other confidential information.

Let’s say the agency breaks into Apple’s key directory service and manages to replace the public keys of the former group with ones under their control without Apple noticing, or finds an exploit that lets them fool copies of Messages into accepting alternative public keys. (These scenarios are extremely unlikely, but Apple admits that it’s not impossible to subvert the delivery of public keys from a central source.)

Without key verification, if such an exploit were carried out, intelligence agents could communicate with people in the latter group using suborned accounts, and iMessage wouldn’t notice. That’s because the end-to-end connection would switch to the new key associated with the contact, a normal occurrence when public keys change, and the conversation would continue. The reporter or politician would have no idea that they were actually talking to intelligence agents.

However, with Contact Key Verification in place, while the public key could ostensibly be replaced without notice, the signature associated with that public key could not be changed. Messages would try to validate the information using the public transparency log, determine the key had changed without a new one-to-one validation step, and throw a warning.

Background: It’s All about the Key Directory Service

The true purpose of Contact Key Verification is to provide security underpinnings to an online interaction. Apple isn’t helping you verify that the other person is the person you think they are. That’s entirely on you! You have to know who they are, know their phone number or email address, and potentially know things about them that couldn’t be learned online.

When you deploy Contact Key Verification with someone you already know, you upgrade an existing conversation from “I think I know this person” to “I know this person, and we now have an out-of-band encryption verification step to keep our conversations secure and tamper resistant.”

All you have to do is pull up an existing conversation and then use some trusted method to read the provided code, as you can see below. If the code matches, you each tap Mark As Verified.

You want to exchange this number through a method other than Messages: all Messages communications are in-band (using the same pathway as the one you’re trying to secure), and you want a separate out-of-band pathway that can’t be subverted. Security experts typically recommend you do this in person or by secure end-to-end video where you can see each other (FaceTime, or Zoom with its end-to-end option enabled). You should also be able to rely on a non-secured voice call, but you may want to have established some answers or code words to eliminate the possibility of an attacker using an AI voicebot to fool you—with a sufficient sample of the target’s speech, they’re pretty good.

The goal of these out-of-band methods is to confirm that the other person retains control of their Apple ID and devices; the verification process aims to confirm who has the account password and second factors.

If the numbers don’t match in the above process, but you’re sure you are each the person the other believes you to be, something bad has happened: possibly some sort of man-in-the-middle attack between the two of you or manipulation of Apple’s key server or transparency log. At that point, you would need to contact someone with authority to figure out what has happened: that might be an employer, a trusted person at a non-government organization like Citizen Lab, Apple, or the FBI, depending on who you and the other person are, and what kind of private information you planned to exchange.

In nearly every case, however, the validation phase of Contact Key Verification should just work—the chance that the security of Messages or Apple’s key directory service has been breached is extremely low. The mere existence of Contact Key Verification may deter advanced attacks that would now fail because they’d be noticed.

Also, because this system is predicated on previous acquaintanceship and an existing iMessage conversation, it can’t be subverted by another party pretending that they have the verification code you read. If they say, “Yes, my code matches,” when yours is “1234 5678” and theirs is “8765 4321,” and you tap Mark as Verified—it gets them nothing. If they’re in the same conversation, the code will be identical, no matter how they gained access to it; if they’re not in the same conversation with you, the code won’t match, and they can’t use your reading of the code to their benefit. In fact, the verification code can also identify when something has already gone wrong and provides a starting point for monitoring future changes.

Looking at it another way, this explains why Apple notes someone with a “public persona” could post a verification code online without risk. When someone wants to start an iMessage conversation with a public figure, they rely on that public element as proof that the public figure is who they say they are. Further, because Apple associates their public key with the email addresses and phone numbers associated with their Apple ID account, someone contacting them and verifying their code could only face an imposter if the hijacker had taken over the public figure’s Apple ID account.

Contact Key Verification is a solution to an issue known for years. Way back in 2016, security researcher Matthew Green explained several of iMessage’s fundamental design problems, with one of the worst being “iMessage’s dependence on a vulnerable centralized key server.” (Another was Apple’s failure to publish the iMessage protocol, which remains a concern. I wrote a Macworld column about these failings in 2016.)

Apple bluntly agrees in the blog post that its iMessage system is vulnerable to such attacks:

While a key directory service like Apple’s Identity Directory Service (IDS) addresses key discovery, it is a single point of failure in the security model. If a powerful adversary were to compromise a key directory service, the service could start returning compromised keys — public keys for which the adversary controls the private keys — which would allow the adversary to intercept or passively monitor encrypted messages.

Let me dig into the key directory service—Apple’s Identity Directory Service—a little more. In iMessage conversations, your devices generate unique, private encryption keys that Apple never has access to—these keys are never transmitted to Apple. Since iMessage launched, with its secure end-to-end encryption, the first device you logged into iCloud using your Apple ID account created a locally held pair of public-private keys. As you add new devices to your iCloud account, each new device performs a key exchange with the other devices in your iCloud set so that each one can encrypt and decrypt messages.

You may have been baffled by this key exchange because Apple explains it poorly. When one of your devices says you need to enter the passcode/password of another of your iCloud-connected devices and the passcode/password won’t be transmitted to Apple, you’re seeing the key exchange process. When you add a device to your iCloud set, you have to enter a secret—the passcode or password—known only to you about another device in your existing iCloud set. That other device has encrypted various key information using its passcode or password (among other information).

As a practical example, let’s say you have an iPhone and a Mac logged into iCloud when you buy a new iPad. When you log in to iCloud on your iPad, after the home screen appears, you should be prompted to enter the passcode for your iPhone or the login password for the account on your Mac associated with that Apple ID. When you do, that enables your new iPad to decrypt the information associated with your iCloud account, giving it access to Messages in iCloud data, iCloud Keychain information, and other encrypted details. Your iPad then encrypts its unique keys and shares them over iCloud with your other devices. This device-only key exchange process enables your devices to share unique key information about which Apple knows nothing.

For iMessage conversations, there’s another process. Apple’s Identity Directory Service stores the public part of a public-private key pair as part of an approach known as public-key cryptography used across all of Apple’s end-to-end encryption systems. Public-key cryptography, widely used across Internet and computer systems, allows people to exchange securely encrypted data without a previous relationship because the public key in the pair can be freely shared without disclosing any portion of the private key. The private key is used for decryption and cryptographically signing data to prove the initiator’s identity and that the data hasn’t been tampered with. Your device keeps and protects the private key, which never leaves the hardware; on Intel Macs with a T2 chip or any iPhone, iPad, or Mac with Apple silicon, it’s locked inside the one-way Secure Enclave. The public key confirms the identity of anything signed with the private key.

The weakness in public-key cryptography is that there’s no inherent part of the key-generation protocol that lets other parties validate who owns a given public key. That’s where infrastructure gets built. Back in the days of Pretty Good Privacy (PGP), keyservers abounded. Later, Keybase offered a more modern solution, but it still relied on a lot of trust. Now owned by Zoom, Keybase never achieved mass adoption. Apple’s Identity Directory Service leverages Apple’s control over every piece of the encryption software, device hardware, and server technology—and even then, Apple admits that security researchers are correct: it’s not enough for the highest degree of protection. This admission comes after Apple has seen many government-driven exploits of and via Messages through spyware—it even sued NSO Group over this (see “Apple Lawsuit Goes After Spyware Firm NSO Group,” 24 November 2021); the suit is slowly progressing through the courts.

To mitigate the weakness of a directory of unencrypted public keys provided by devices, Contact Key Verification adds an extra key, described earlier. This unique key, shared only among your iCloud device set, uses a one-way cryptographic process against your iMessage public key to produce a signature. That signature can’t be forged—one must have the original key, which exists only on your devices, to produce a signature that can be validated. (This is another reason why protecting physical access to your devices and their passcodes/passwords is so utterly important! Never share a passcode with anyone you wouldn’t trust with access to your bank account, and never enter a passcode in public; see “How a Thief with Your iPhone Passcode Can Ruin Your Digital Life” (26 February 2023) and “How a Passcode Thief Can Lock You Out of Your iCloud Account, Possibly Permanently,” (20 April 2023).

This signature is essentially cryptographically concentrated into the eight-digit code. Two people seeing the same eight digits provides the missing piece that closes the loop: their devices become the source of truth about the keys for those two people’s iMessage accounts, not Apple’s Identity Directory Service. If anything changes, each device knows enough to spot discrepancies in Apple’s Identity Directory Services or the transparency log.

Contact Key Verification goes a long way towards giving iMessage the best-in-class robustness that security researchers have been telling Apple is possible for some time. It may seem minor for everyday users, but it’s a giant leap forward for those whose livelihoods—or lives—could be threatened by compromised communications.