#1508: Zoom’s security and privacy flaws, videoconferencing options, Apple buys Dark Sky, using a trackpad with an iPad, what can Big Tech do for humanity?

“Strange days have found us,” sang Jim Morrison of the Doors, and we have an issue of TidBITS for you to match. We lead off with the news that Apple has purchased the Dark Sky weather service and app, which will undoubtedly shake up the market for weather apps. Adam Engst shares a link to an essay that asks how social media platforms might be able to use their persuasive powers for good. Julio Ojeda-Zapata digs into the details of how trackpads and mice work with iPads running iPadOS 13.4. Glenn Fleishman rounds out the issue with an overview of videoconferencing options and a (currently) comprehensive list of the privacy and security issues with the massively popular Zoom teleconferencing software. Notable Mac app releases this week include Pixelmator Pro 1.6, Apple Configurator 2.12, Little Snitch 4.5 4/3/20, Pages 10, Numbers 10, and Keynote 10, Carbon Copy Cloner 5.1.16, Fantastical 3.0.9, Banktivity 7.5, and Audio Hijack 3.7.

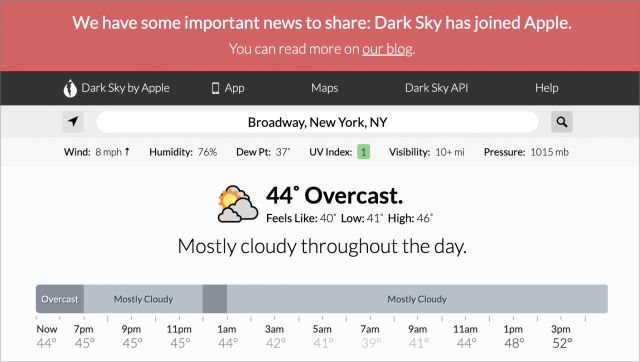

Apple Acquires Dark Sky Weather Service and App

Apple has acquired hyperlocal weather company Dark Sky. We’ve long been fans of both the Dark Sky app itself, available for iOS and on the Web (see “Dark Sky 5 Offers Hyperlocal Weather Forecasts for iOS,” 7 August 2015), and apps powered by the Dark Sky API (see “CARROT Weather Predicts Cloudy with a Chance of Snark,” 22 January 2018). Dark Sky’s data stands out because it can accurately warn of rain and other inclement weather minutes before it happens.

While we hope this acquisition will give the iPhone’s built-in Weather app and Siri’s weather forecasts a much-needed boost, there are some unfortunate side effects of the Apple acquisition:

- Unsurprisingly, the Android and Wear OS apps are no longer available to download. They will continue to work until 1 July 2020, and existing subscribers will receive refunds.

- Apple plans to cut off the Dark Sky API at the end of 2021, which is bad news for the many weather apps that rely on Dark Sky’s excellent data.

- The Dark Sky Web site will continue to offer forecasts, weather maps, and embeds until 1 July 2020, but will remain active after that to support the API and iOS app.

However, the Dark Sky iOS app will remain available to purchase and continue to work, at least until Apple builds its functionality into iOS.

How Can Tech Step Up for Humanity?

Tristan Harris and Aza Raskin of the Center for Humane Technology have penned a Medium post in which they pose the radical question, “How can tech step up for humanity?” They’re mostly thinking about social media platforms like Facebook, LinkedIn, and Twitter, which have largely restricted themselves to simple attempts to provide reliable information and weed out actively harmful posts. Those are positive steps, of course.

But mere information will always struggle against the many insidious ways in which social media platforms are used to persuade and manipulate users. Just look at the reports from the UK of people torching cell towers because of insane conspiracy theories that claim 5G wireless is somehow responsible for the spread of the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus. Deleting such posts would be helpful, but even more so would be to change the minds of the would-be arsonists.

Harris and Raskin suggest various ways that social media platforms could employ commonly used persuasion principles to accelerate the kinds of behavior necessary to slow the spread of the coronavirus. Give their thoughts a read and chime in—what other ways could these platforms benefit the public health at a time when it’s so critical?

Similarly, outside the social media space, major tech companies like Apple (see Tim Cook’s video), Google, and Microsoft have focused on donating money and supplies to support public healthcare efforts, helping distribute basic information, and keeping their systems running through traffic increases of 10 to 20 times normal. That’s all good, but is it really putting our best and brightest tech minds where they could have the most impact? What would you do if you were in charge of one of these tech giants?

The iPad Gets Full Trackpad and Mouse Support

Apple has long positioned the iPad as a device for getting real work done. The company has made this argument with increasing emphasis in recent years—even using a snarky “What’s a computer?” pitch in a commercial that touts the iPad’s productivity prowess.

Yet Apple stubbornly resisted adding an obvious interaction method—trackpad and mouse support—despite user requests. Without such a capability, the iPad fell short as the notebook alternative Apple claimed it to be.

Last year, Apple added rudimentary pointing device support to iPadOS but positioned it as an accessibility feature.

This year, Apple is going all-in. With iPadOS 13.4, the company is rolling out robust, general-purpose trackpad and mouse support that takes cues from the Mac but offers a fresh spin in many ways.

Device and Peripheral Compatibility

First off, iPadOS 13.4 is compatible with the following models of the iPad:

- All iPad Pro models

- iPad Air (2nd generation and later)

- iPad (5th generation and later)

- iPad mini (4th generation and later)

All of these models work with iPadOS 13.4’s trackpad and mouse support, which in turn is fully compatible with Apple’s current Magic Trackpad 2 and Magic Mouse 2. Apple says it also works with the original Magic Trackpad and Magic Mouse, but neither of those older devices supports multi-touch gestures. Third-party mice connected via Bluetooth or USB also work, as do, reportedly, third-party trackpads, but I had none to test. I suspect they wouldn’t support multi-touch gestures either.

In addition, Apple has announced a pricey iPad Pro keyboard case, the Magic Keyboard for iPad Pro, which incorporates a trackpad (see “Hell Freezes Over: Apple Ships an iPad Pro with an Optional Trackpad,” 18 March 2020). The accessory, due in May, will work with all versions of the 11-inch iPad Pro and the third-generation and later versions of the 12.9-inch iPad Pro.

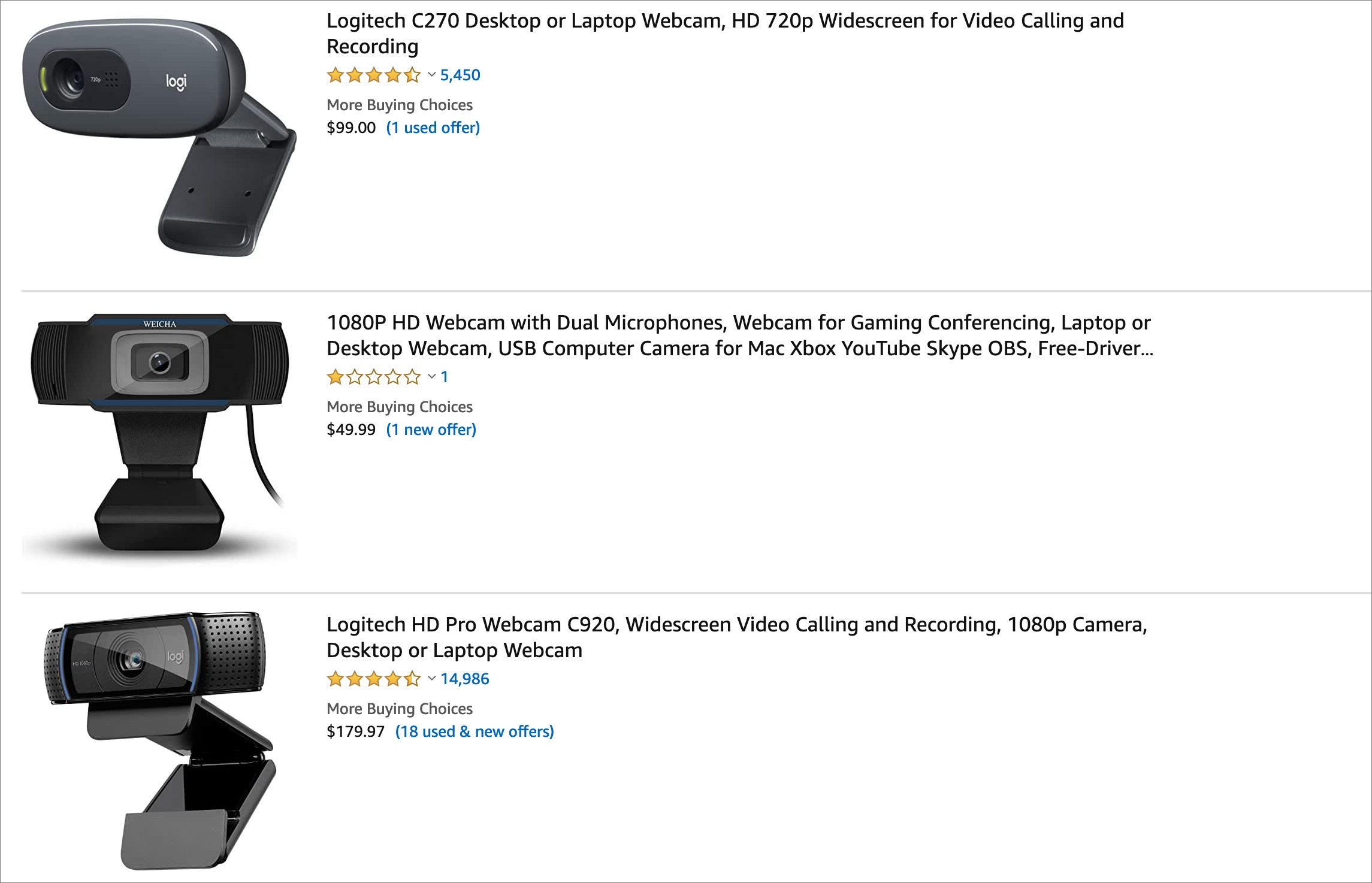

Third-party accessory makers such as Logitech and Brydge are following suit, releasing iPad keyboard cases with built-in trackpads that work with iPadOS 13.4.

I find all of this exciting because I’ve made many attempts to use iPads in work scenarios over the years, but I often ended up aborting my experiments due to the platform’s limitations compared to traditional computers. Lack of pointing device support was one such iPad shortcoming that, well, stopped me short.

A Brand New Kind of Cursor

Apple has clearly put a lot of thought into how trackpad and mouse support on the iPad would have a personality all its own. The cursor, for starters, looks different. It’s not a traditional arrow or a pointing hand. Instead, its default state is a small, translucent circle intended to evoke a rounded fingertip. What’s more, the cursor morphs depending on how it is being used and where it is positioned. For instance:

- Its shade shifts subtly depending on the background—darker on a lighter background, lighter on a darker background. The Mac pointer is black with a white border regardless of its background.

- It transforms into a vertical I-beam when hovering over text to let you insert and highlight words. When moving text around, the cursor reverts to the circle.

- When hovering over a button or other interface element, it becomes a rectangle that envelops the on-screen control, highlighting what a tap would affect.

- When hovering over an app icon on the Home screen, it vanishes temporarily but enlarges the icon slightly as a cue that you are in the right place for a tap or hard press.

- It transforms into directional arrows under some circumstances, such as when you are resizing columns or rows in a spreadsheet. (This one isn’t unique, roughly the same thing happens on a Mac.)

[Editor’s note: Apple uses the term “cursor” in its marketing materials for this iPadOS feature, so we’re following its lead in this article, even though the Apple style guide is quite clear about not using the word “cursor,” saying: “Don’t use in describing the macOS or iOS interface; use insertion point or pointer, depending on the context.” We’re trying to get guidance from Apple on whether the use of cursor was a mistake or a style change. –Adam]

Setting Up the Magic Trackpad 2

I did most of my testing with a Magic Trackpad 2. Pairing the trackpad with my 11-inch iPad Pro worked as expected in Settings > Bluetooth, where I saw the trackpad appear under Other Devices, selected it, and tapped a Pair button to confirm. I could also have connected my trackpad to the iPad using a Lightning cable.

Once I got the trackpad working, I spent a minute gleefully whizzing the cursor back and forth across my iPad Pro screen—much as I did long ago when I first used a Mac and its then-novel point-and-click functionality.

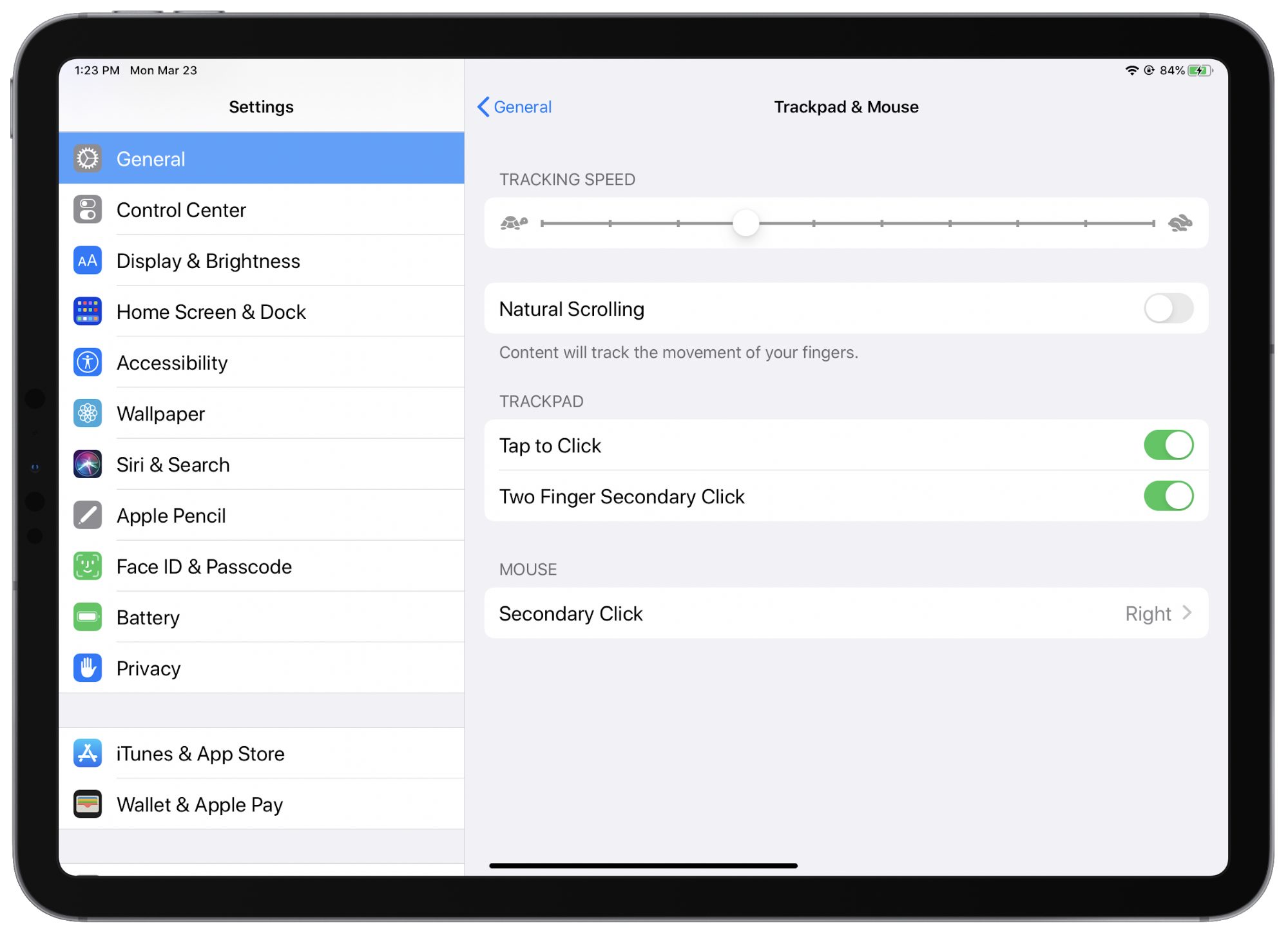

Trackpad behavior is adjustable, much as it is on a Mac, but options are scattered throughout Settings instead of consolidated in one spot.

Go to Settings > General > Trackpad, and you can tweak the tracking speed, turn “natural” scrolling on and off, and opt to use Tap to Click and Two Finger Secondary Click. (Note: “Trackpad” will appear as “Trackpad & Mouse” if you have also set up a mouse. I’ll get to the mouse support in a bit.)

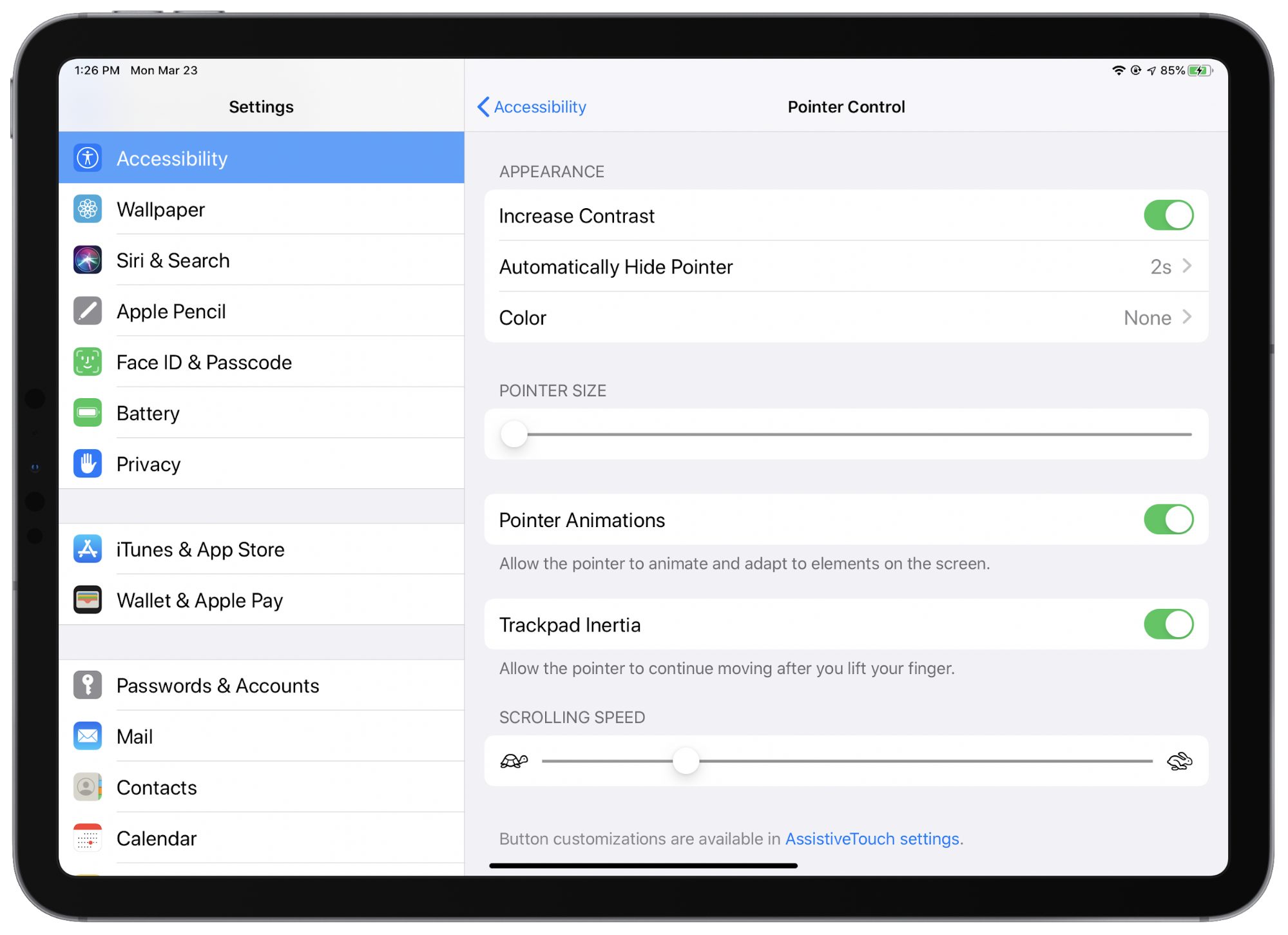

You can find additional adjustability controls in Settings > Accessibility > Pointer Control. Here you can customize trackpad inertia, the appearance of the cursor—color, size, degree of translucence—and how long it remains visible on the screen when idle. You can also prevent the cursor from animating and adapting to elements on the screen, as described above, if you want a more traditional and static pointing experience.

Trackpad Gestures on the iPad

For basic use, you just move your finger around on the trackpad and press to click, which mimics what happens when you use your finger on the iPad screen and tap.

The real fun begins when you use trackpad gestures, which in many cases mirror or resemble those you have long used with your finger on the iPad’s screen. Others mimic what you’re used to on a Mac’s trackpad.

One Finger

With one finger, you would move the cursor:

- To the bottom of the screen and then push against the edge (when an app is on the screen) to reveal the Dock. Give another nudge, and you return to the home screen. But if you nudge and hold, you open the App Switcher.

- To the bottom of the screen until it snaps onto the home indicator on a Face ID-based iPad Pro. Click it to hide all apps and reveal the Home screen and Dock.

- To the bottom of the screen (on the Home screen) and then push against the edge to open the App Switcher.

- To the upper-right corner and then click the battery indicator to open Control Center. You can also move to the upper-right corner and then nudge upwards to see Control Center.

- To the upper-left corner and then click the date to open Notification Center. (The date appears only if the Today View time and date display isn’t showing on the main Home screen; scroll down in Today View or switch to another Home screen to see the date in the upper-left corner.)

- To the right side of the screen and then push against the edge to reveal any open Slide Over apps (this works only when you’re in an app). Repeat to hide the Slide Over window.

- To the top of the screen and then push against the edge for Notification Center.

- To an app icon and then click and hold for a Quick Actions menu. Continuing to hold engages the wiggling icon Edit Home Screen functionality.

- To an app in the Dock and then click, hold and drag to place it in Slide Over or beside another app in Split Screen.

- Onto text and then tap, double-tap, triple-tap, or tap/drag for cursor insertion, word selection, paragraph selection, or text movement.

Additional multi-touch gestures are available using multiple fingers, much like those directly on the iPad screen.

Two Fingers

With two fingers, you would:

- Swipe left or right to move between Home screens.

- Swipe left or right to move through App Switcher screens.

- Click or tap for contextual information (such as on an app for Quick Action options, or on Safari links for Web-page previews).

- Pinch to zoom in and out within supported apps (such as photo and map apps).

- Scroll vertically through documents and Web pages.

- Swipe left or right in Safari to page-flip backward and forward.

- Swipe left to navigate backward in nested menus, such as moving back up from Settings > General > Trackpad.

- Flick an app (upward or downward, depending on how Natural Scrolling is set) in the App Switcher to force-quit it.

- Flick a notification (upward or downward) to dismiss it. (You can also swipe a notification left or right in Notification Center to access the usual management controls.)

- Flick vertically on the Home screen (upward or downward) to reveal Spotlight.

Three or Four Fingers

With three or four fingers, you would:

- Swipe left or right to move among open apps.

- Swipe left or right on the Slide Over panel to switch between apps there.

- Swipe up on the Slide Over panel to see all available apps there. (You can then flick apps away with two fingers if you’re done with them.)

- Swipe up to go to the Home screen from an app or Notification Center, to go to the first Home screen if you’re on a secondary one, to stop the wiggling icons while editing the Home screen.

- Swipe up and hold briefly (or execute a longer upward swipe) to reveal the App Switcher.

Five Fingers

As far as I know, there’s only one five-fingered gesture:

- Pinch inward with all five fingers to open the App Switcher.

Apple’s Craig Federighi does a nice job of running through basic gestures in a video that was supplied to some tech journalists—you can see it in this article on The Verge.

Using Magic (Or Other) Mouse

Most of Apple’s pointer focus has been on trackpads, which is in line with the attention it has long lavished on the trackpads built into its laptops.

However, Apple has built in decent support for the Magic Mouse 2 and third-party mice. You connect them with Bluetooth or USB (directly to the iPad, with an adapter if needed, or indirectly via a hub or dock).

Setup is a bit different than with a trackpad. Go to Settings > General > Trackpad & Mouse and fiddle with Tracking Speed and Natural Scrolling, as before. But at the bottom, there is an option to assign Secondary Click functionality to either the right or the left mouse button (the original Magic Mouse gets this option too).

Additional mouse settings are deeply buried. Go to Settings > Accessibility > Pointer Control, as before, and tweak those settings as you would for a trackpad. That screen also informs you that “button customizations are available in AssistiveTouch settings.” Click the link to go there.

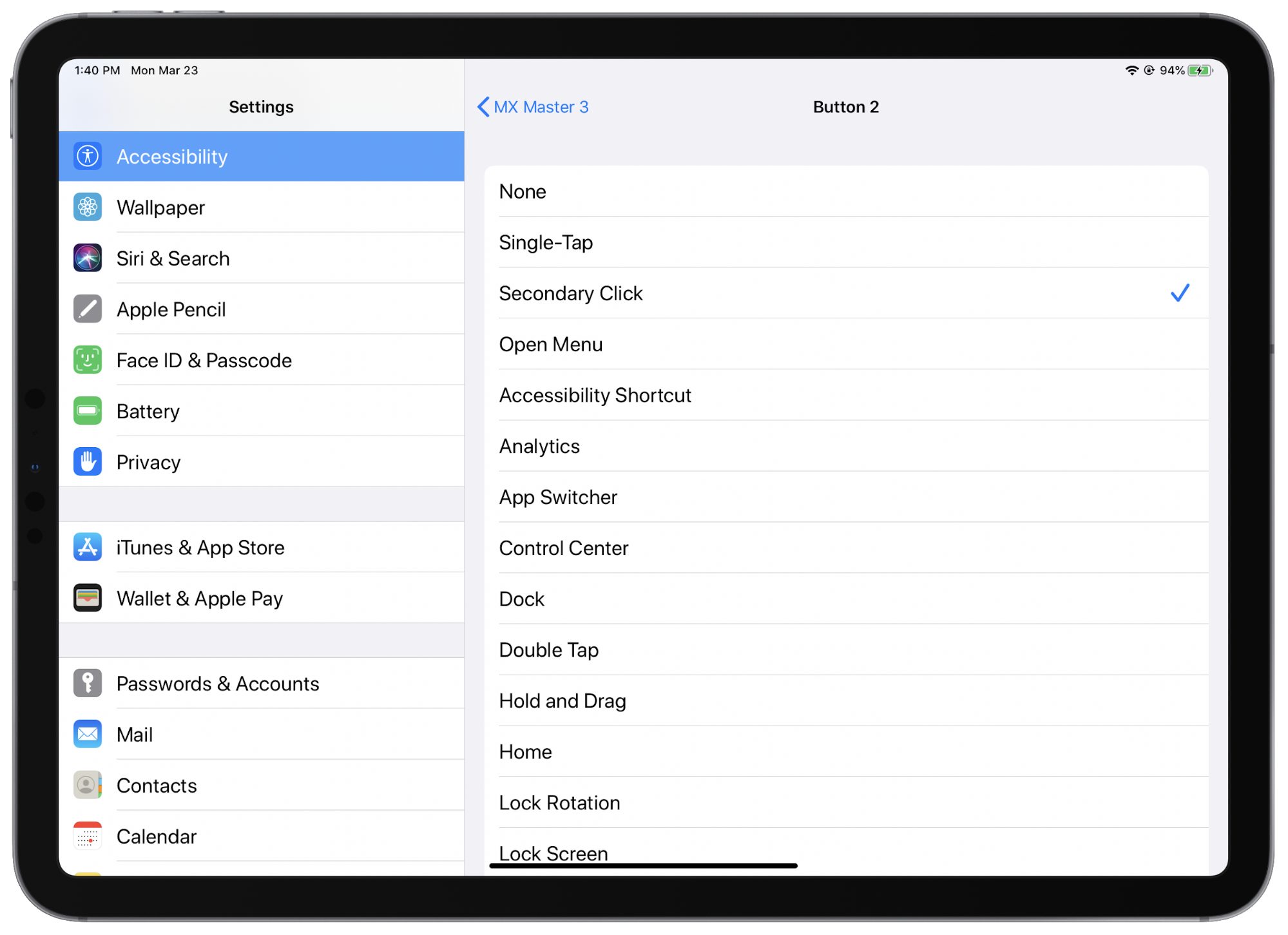

AssistiveTouch is where you can customize the functionality of a mouse’s buttons, ranging from the dual touch surfaces on the Magic Mouse 2 to devices like the Logitech MX Master 3 that are chockablock with buttons and scroll wheels.

Select one of the connected devices. You’ll find basic functions mapped to one or more buttons, but if you want to set up additional functions, click Customize Additional Buttons. You’ll be prompted via a dialog to press the button you want to customize. When you do so, a long list of button functions appears. Pick one. Repeat for more buttons (including scroll wheels on some mice that have button-click capability).

The Magic Mouse 2 works better with iPadOS 13.4 than traditional mice because its touch surface makes it a bit like a trackpad with a few supported gestures. With finger flicks, you can scroll vertically through documents and Web pages, and navigate horizontally through Home screen views, pages in Web browsers or news apps, and the like. You can also flick with the cursor positioned roughly in the center of the Home screen to reveal Spotlight.

Other functions are more universal and applicable to any mouse. Any of the trackpad gestures that involve moving the cursor to an edge and then nudging should work well with all devices.

But there are a few mouse-only variations. When in an app, you reveal the App Switcher by moving your cursor to the bottom of the screen and onto the home indicator (for a Face ID-based iPad Pro), then swiping upward. I’m not sure if there’s a similar gesture for Touch ID-based iPads.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, I saw some glitches. With my Logitech mouse, I once experienced intermittent cursor-tracking jerkiness that rendered the mouse all but unusable, and only an iPad reboot set it right.

Laptop Alternative, At Last?

Trackpad and mouse support goes a long way toward making the iPad the productivity powerhouse I have long yearned for it to be.

Along with Bluetooth keyboard support—I’m using a standard wireless Magic Keyboard 2—this means, among other things, that I no longer have to keep the iPad close up when trying to get work done, which can get uncomfortable. Now I can set the iPad farther back on my desk and raise it to eye level for ergonomically safer productivity sessions. A variety of stands from third-party accessory makers are available for this purpose; I grabbed my Super Stump, which is marketed as a lap stand but works as effectively on a work surface.

Being able to separate an iPad from its keyboard and trackpad feels like a seismic shift. I can finally see myself using the iPad as a primary productivity device—such as the computer I use as a Web editor at the St. Paul Pioneer Press. I am making some attempts at relying entirely on the iPad, and they are going reasonably well, although I imagine it will be some time before everything seems natural.

But it’s still early days with the iPad’s trackpad and mouse support, with rough edges yet to be smoothed out. Many apps are not yet fully compatible with iPadOS 13.4. This means, among other things, that the cursor’s morphing capabilities in such apps (switching from circle to I-beam to translucent rectangle, and so on) aren’t present. Worse, some Web sites are borderline unusable. The slider controls on the YouTube site, among others, don’t respond to cursor control.

Although I have yet to lay my hands on the Magic Keyboard for iPad Pro or any other such iPad keyboard, I must confess to some skepticism about their Lilliputian trackpads. They resemble the tiny trackpads on the keyboard covers for Microsoft’s Surface tablets, which have never impressed me. Granted, there’s not much space on the Magic Keyboard, but the huge trackpads on Apple laptops are appealing.

I am, however, having a ball using my iPad Pro with the Magic Keyboard 2 before me, the Magic Trackpad 2 to its left, and the Magic Mouse 2 to the right. It’s just magic.

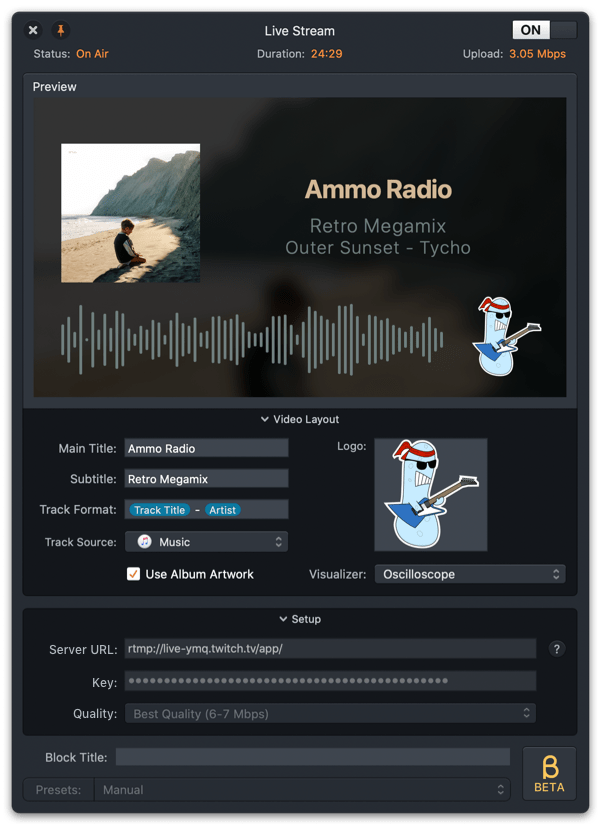

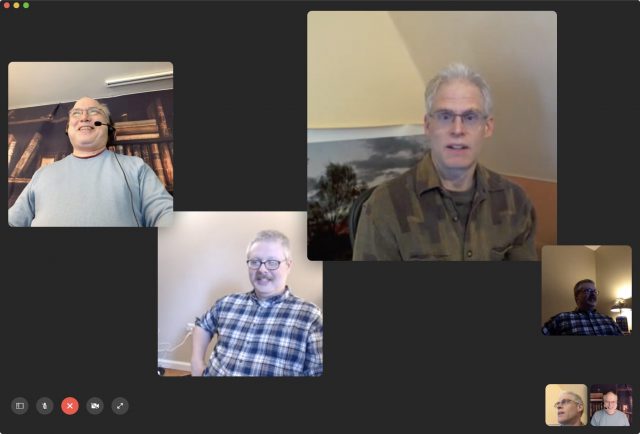

Videoconferencing Options in the Age of Pandemic

Videoconferencing is by no means new. Heck, TidBITS has been writing about it since at least 1994 (see “The Flexible FlexCam,” 18 July 1994, in which Adam Engst pondered doing an Internet video show over a decade prior to YouTube’s launch). But a technology that once required specialized rooms, A/V gear, and telecommunications equipment—and was hyped as the future of businesses as an end to expensive, time-consuming travel—is now just another mundane but useful part of business and personal life.

Then the coronavirus pandemic arrived. Something that was neat to use, efficient for remote workers and decentralized teams, and effective for some forms of distance learning suddenly became essential for businesses trying to keep continuity in their work, students sent home from school, and friends and family who wanted to socialize while cut off from normal get-togethers.

You have likely already been caught up in using videoconferencing in ways you never did before. But if you’re trying to wrap your head around the different platforms—you’re in good company there—this article will help answer many of your questions.

Let’s look at popular videoconferencing options. I start with systems that are free or have a free tier, taking an in-depth look at each. In a final section, I briefly discuss paid options, including both standalone services that offer low-cost service tiers and those that may be included in a subscription your organization already has.

It’s important to acknowledge that you might not have a choice about what videoconferencing tool you wind up using. For work, your company or workgroup may have settled on a particular platform that you’re obliged to use. Among friends and family, it usually ends up being the service that everyone either already has installed or that you can convince other people to download or configure. It’s entirely likely that you’ll install all of these apps to be able to communicate with different groups.

For each service, I end with an overview of key features.

FaceTime

Apple’s free FaceTime audio and video chat software and service works only on the Mac, iPhone, iPad, and iPod touch (plus FaceTime Audio on the Apple Watch)—there’s no Web-based component. Everyone relies on the bundled FaceTime app. If your group doesn’t all have Apple gear, FaceTime is a non-starter, so skip to the next section.

If you haven’t used FaceTime for video recently, you might not realize that Apple upgraded from a one-to-one video limit (and up to nine people for audio-only calls) before December 2018 to its current Group FaceTime limit of 32 people using just audio or both audio and video. You might also have heard that Group FaceTime suffered from a huge privacy bug that led Apple to disable Group FaceTime in January 2019; the company fixed that and restored service in February 2019 (see “Apple Fixes Group FaceTime Bug; Promises to Improve Bug Reporting Process,” 1 February 2019).

All iOS devices must run iOS 12.1.4 or later (or iPadOS) to connect, while Mac users must be using macOS 10.14.3 Mojave or later. Not all iOS devices compatible with iOS 12.1.4 may participate in video calls, however. Apple has a complete list, but devices released in the last five years should just work. Earlier hardware that can run iOS 12.1.4 can join a Group FaceTime chat in audio-only mode.

Group FaceTime is among the simplest of the videoconferencing options, in part because there’s no software to install. But it also has the fewest features. You can’t share a screen or a presentation, and it lacks moderator controls. The person originating the call isn’t a host as such, and nobody in the call can mute other people, or manage any features. Anyone in the call can add another person, too.

Apple doesn’t offer a URL you can share to join a Group FaceTime call, unlike every other option we tried. Instead, you must be invited into a session. You also can’t boot people from a call, which would be helpful when you accidentally invite the wrong contact or someone doesn’t pick up—their icon sticks around forever. The only workaround is to end the call and start a new one with a different set of people. (People can choose to leave, however.)

Group FaceTime also doesn’t include a recording option. If capturing a session is useful for a business meeting, a lecture, or other reason, you can use iOS and macOS screen-recording tools:

- In iOS, open Settings > Control Center > Customize Controls. Add Screen Recording to the list of included items at the top by tapping the green + plus sign next to its name under the More Controls list. Then, when conducting Group FaceTime, swipe to reveal Control Center and tap the Record button.

- In macOS, launch QuickTime Player. Choose File > New Screen Recording. Select the appropriate mic input from the dropdown menu next to the red Record button. Then, click the Record button, drag a selection around the FaceTime window, and click Start Recording. Use the recording menu in the system toolbar to end the session.

This recording advice also works for other services, whether or not they include in-app recording.

Although FaceTime lacks Zoom’s clever virtual background feature—we could see Apple adding it, given that it’s a great use of augmented reality—it has a lot of other items on offer in iOS and iPadOS: Animoji (to replace your face with an animated cartoon), video filters, shapes, activity stickers, Memoji stickers, and emoji stickers. Kids will probably particularly like FaceTime effects.

One notable negative of Group FaceTime is that people’s faces swim around in the display, moving and expanding to indicate who’s speaking. It can be dizzying, or even nausea-inducing. As far as we can tell from our testing, you can’t disable it, even by turning off Reduce Motion in System Preferences > Accessibility > Display.

For presentations, Apple provides an option I had never heard about before researching this topic: Keynote Live. It lets you broadcast a Keynote slide deck to as many as 100 people. They can view it with the Keynote app or using a browser, and viewers require no special software or account. However, there’s no audio or video component, no interactive chat, and no way for viewers to submit a question; you have to deliver all that separately, so you might want to use a service like Zoom, described below, to deliver an audio and chat portion.

Overview of FaceTime:

- Platforms: macOS, iOS, iPadOS

- Maximum video participants: 32

- Screen sharing: No

- Moderation controls: None

- Extras: Fancy effects and stickers in iOS and iPadOS version

Google Hangouts

Google Hangouts may seem like a better option for more people than FaceTime, Skype, or Zoom because Google doesn’t require desktop users to download and install an app—or even necessarily a plug-in. Everyone must have a Google account and must be logged into it, but that’s free and extremely common anyway. Hangouts supports macOS, Windows, iOS, and Android, as well as ChromeOS (used on Chromebooks) plus Ubuntu and Debian-based Linux distributions.

Here’s what participants need:

- Google Chrome or Mozilla Firefox browsers on a computer running macOS, Windows, or ChromeOS: No plug-in required. Hangouts uses a Web component in both browsers for in-app videoconferencing. (An optional Chrome extension adds features.)

- Safari (macOS) or Internet Explorer (Windows) browsers on a computer: Download a plug-in, but videoconferencing still happens within the browser. Nothing separate needs to launch.

- Mobile devices: Download the iOS or Android Hangouts app.

The consumer version of Google Hangouts offers audio, video, and screen sharing, along with text messaging. Up to 25 people can participate in a video call. As with FaceTime, there are no moderation features, and you cannot record the call directly within Hangouts. Anyone can kick someone else out of a call, but that means any participant can kick out the person originating the videoconference, which seems like a design flaw. And, at least in our testing, once you were kicked out, there was no way to rejoin the call.

The usability of Google Hangouts is terrible. In testing, we spent a large amount of time trying to figure out how to perform some task we thought we remembered Hangouts offering—only to discover that Google has seemingly removed features previously found in Hangouts. It also lacks obvious features found in most other software, such as the capability to see equivalently sized video streams from other participants at once. Weirdly (and unlike Skype), if you start a video call from an existing hangout, the chat within the video call is entirely separate from the text chat in the hangout. We found Hangouts a weak entrant that’s worth using only if everyone else in the group has already agreed to use it.

The reason for the weakness becomes clear when you search for help with Google Hangouts. Google spins up similar services the way rabbits birth kits: too many overlapping products with indeterminate transition periods and nearly indistinguishable names. For businesses, Google now offers the slightly different Hangouts Chat for room-based text chats and Hangouts Meet for videoconferencing. This splits what was once Hangouts into two separate products.

However, Google mashed the two together for consumer users as plain old “Google Hangouts” and for G Suite business users as “Classic Hangouts.” And that mash-up feels painful, as the service handles chat within a video session and chat outside it as separate things. Google plans to remove the video portion of Chat from G Suite’s Classic Hangouts entirely by June 2020—or at least it did, before the pandemic. (And we’re not even going to mention Google Duo, which is a smartphone-only videoconferencing app. Drat, we just did! Pretend it doesn’t exist, because that’s what Google does.)

As a result of all these different services, when you search for help with Google Hangouts, you will almost always find advice aimed at G Suite business users. Computerworld described the situation in an article in January 2020 appropriately titled, “Welcome to Hangouts Hell.”

Overview of Google Hangouts:

- Platforms: Every major platform, including ChromeOS, as well as most Web browsers

- Maximum video participants: 25

- Screen sharing: Yes

- Moderation controls: Anyone can be removed from the call, after which they can’t rejoin

- Extras: None

Skype

Skype has been kicking around the Internet since 2003, starting life as a Voice-over-IP calling program and passing through three owners since. Microsoft has operated Skype since 2011 and seems to feel the need to overhaul the app’s interface regularly in updates that shuffle controls around and change their functions. Skype has also morphed from a consumer-focused text, audio, video, and screen-sharing app into something that’s a hybrid of personal and business use.

Skype lets up to 50 people participate in a videoconference, including screen sharing. People can also join with just audio. (You might see references on Skype’s site and elsewhere to a business flavor, but Microsoft has shifted its corporate users to Teams; see “Consider Paid Options” later in this article.)

Skype is available as a native app on all major platforms, including multiple flavors of Linux. It also comes in the form of a browser plug-in for desktop operating systems that works in Google Chrome and Microsoft Edge. It’s even available for Amazon Echo devices with a screen and for Microsoft’s Xbox One.

Skype is free for Internet-based audio and video calls. To start a video or other session, you need a Microsoft Live account (free) to sign in to the Skype app. Microsoft Live accounts aren’t unusual, particularly with people who use Windows or are invested in Microsoft’s Office suite, but they’re probably not as common as Google accounts among Mac users.

When used with personal accounts, Skype offers no moderation features nor any in-app or in-system recording.

You can switch to a video session after creating a text chat in Skype by simply clicking or tapping a video button (or an audio call by using a phone-handset button).

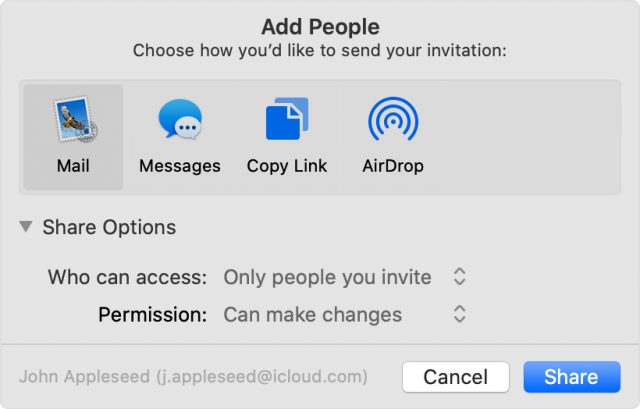

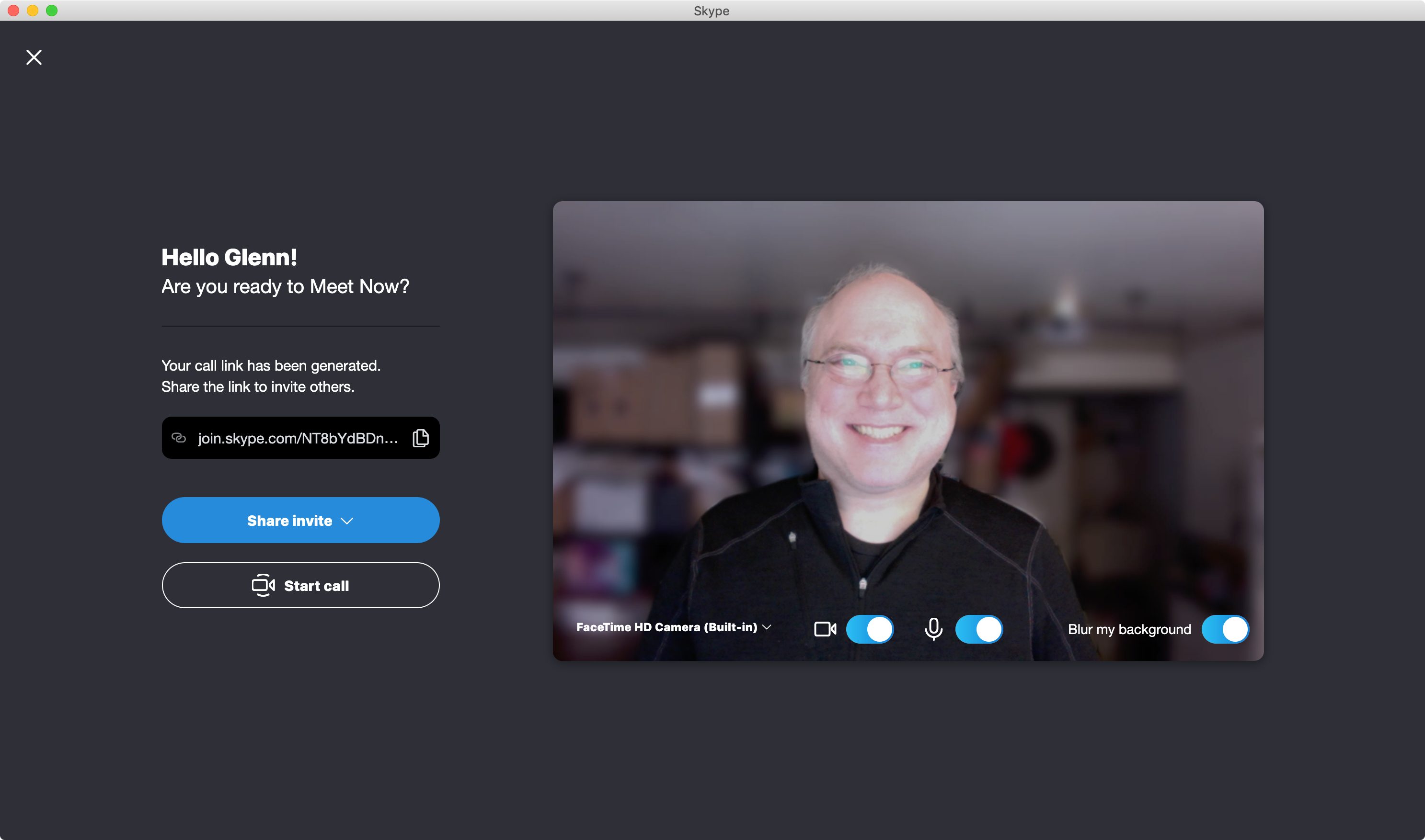

Skype offers two ways to share a group invite. On 3 April 2020, Microsoft added the Meet Now feature. Click the Meet Now button and then copy the link generated or click the Share Invite button for more options. You can distribute that URL and click Start Call to begin. Participants don’t need a Microsoft Live account.

You can also copy a group invite URL from within a chat session or active call and share that. People who receive the URL can join in without having to be invited individually as participants—and you don’t need a Microsoft Live account to join in that fashion, either. However, once someone has the URL, they can’t be permanently removed from a call: they can rejoin after being kicked out.

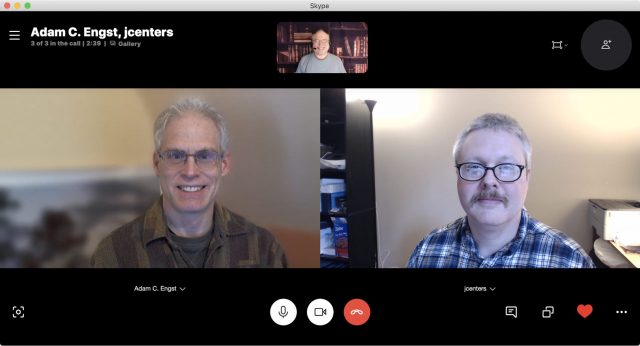

In testing, we were surprised to find that Skype was the best option behind Zoom for a group video call, offering the best combination of options for setting up a call, sharing it, and organizing how you see participants. A blur background feature lets you fuzz away clutter. Skype boasts a number of other useful extras, too, including screen sharing and live text transcription (via a machine-learning algorithm) of conversations that’s shockingly accurate.

Skype suffers from the requirement of setting up a Microsoft Live account for setting up calls that involve a particular set of people. But the option to share a link to others to join can bypass that overhead.

We did find Skype’s interface baffling. You often have to look in five to eight different places in the interface to find the feature you need or hover over a feature to find an arrow to click that reveals more options. Dragging in the wrong place can reconfigure Skype in confusing ways. Overall, however, it offers high-quality videoconferencing and an excellent array of free features.

Overview of Skype:

- Platforms: All major platforms plus Linux, Chrome and Edge browsers, and some consumer hardware

- Maximum video participants: 50

- Screen sharing: Yes

- Moderation controls: Can remove someone from the call, but they can rejoin

- Extras: Moji video clips in text chats, “subtitle” real-time transcripts of calls, image sharing

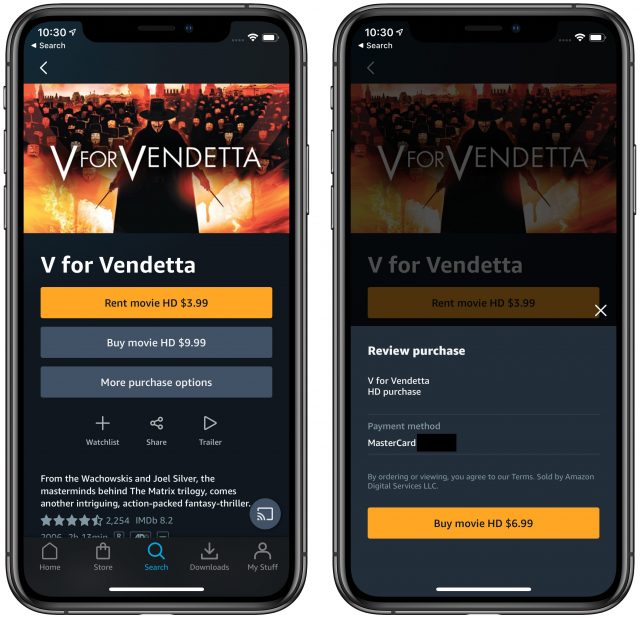

Zoom

In early 2020, Zoom has emerged as the clear winner for large groups, especially with participants who have little or no experience with Internet videoconferencing. The reasons are straightforward: Zoom offers an array of powerful features in its free tier, doesn’t require participants to have a Zoom account, and makes its app download as easy as possible.

Unlike the previous services, which focus on person-to-person connections, Zoom is a professional tool that also works for more casual purposes. Its features are designed for businesses but work well in other contexts. That starts with defining a “host,” who initiates or schedules the call and wields administrative and moderator powers during the session.

Everyone joining a Zoom meeting needs to download a free app, available for all major desktop and mobile platforms. Zoom has a fallback option to a browser component for the five major browsers (Safari, Chrome, Firefox, Edge, and Internet Explorer) that relies on Web standards to work without a plug-in, but it has worse video quality and fewer features.

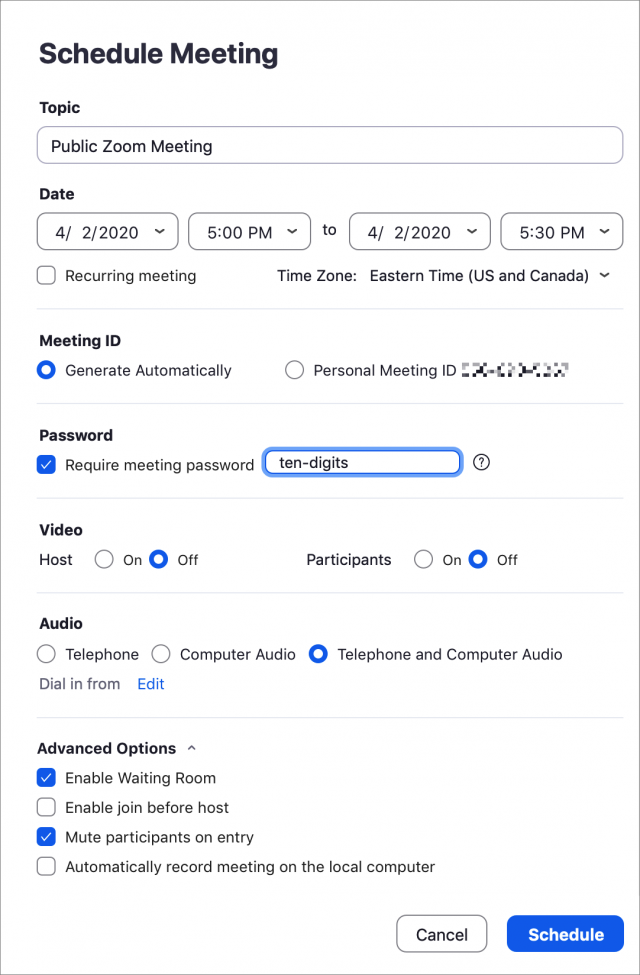

A session starts by a host scheduling or creating a meeting via the Zoom Web site or within the Zoom app, which also provides the primary audio, video, and screen-sharing capabilities. There are also browser plug-ins and integrations for Slack and other group-communication software, but those merely provide scheduling features and let users join a meeting with a single click.

Once you sign up for a free Zoom account, you can create a meeting. Zoom generates a multi-digit meeting ID and a password, the latter of which you can change. As of 4 April 2020, a password is mandatory for all free-tier meetings. The easiest way to share connection information is via a URL (with an encrypted form of the password) that you can copy from your meeting page. A preference lets you avoid embedding the password in the URL if you consider that a security risk. You can also distribute the meeting ID and password in plain text, and people can join by entering them into the Zoom Web site or a Zoom app. In the meeting page, Zoom even provides a link to click that copies a meeting’s details in a neatly formatted text form for pasting into an email or invitation.

You can also create an “instant” meeting in the Zoom app by clicking Start Meeting. Then you can click the info button in the upper-left corner to get meeting details to send to others.

People can also call into a conference the old-fashioned way, by dialing a phone number, but Zoom has had to restrict that feature for free hosts at times due to current levels of usage.

Participants don’t necessarily need a Zoom account to join a meeting. When configuring a meeting, the host can choose whether people without a Zoom account may join.

When a participant opens a Zoom URL, the company’s Web site provides a link to download apps, if necessary, and tries to launch the app if it’s installed. If there’s a problem downloading, a visitor can opt to use the browser-based alternative.

At the free tier, Zoom meetings can last only 40 minutes (which some people consider a feature), though you can start meetings back to back and the same people can join successive sessions. If you work in K-12 education in many parts of the world, Zoom currently offers an upgrade for free accounts to conduct meetings of up to 24 hours, its standard maximum limit. Read the company’s blog post for details if your account hasn’t already been bumped up. Anecdotally, and in my experience, it seems like Zoom has enabled a silent “kindness” upgrade, too. At 40 minutes, you may see a message that says your session has been extended or offering to start a new session with the same parameters.

Up to 100 people can participate in a meeting. By default, anyone can share their screen, though a host can restrict that. In-app recording to the local machine is available in the free tier, too.

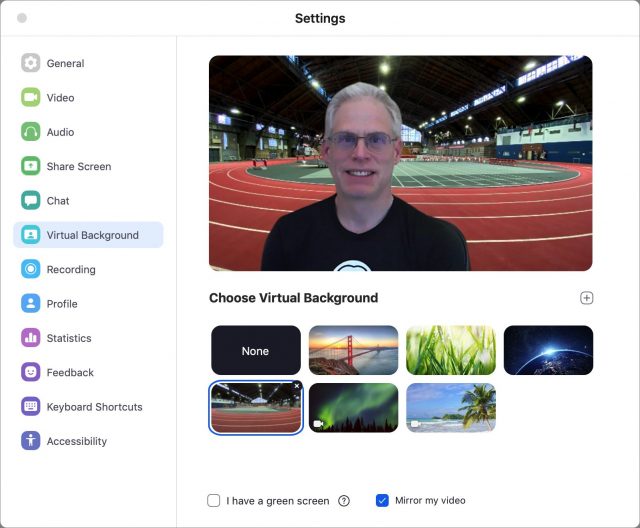

Although Zoom unsurprisingly lacks the sort of silly features Apple built into FaceTime, Zoom’s virtual background feature is hugely popular. It lets you upload a photo that appears behind you and hides your messy office or bedroom. To add a virtual background, open the Zoom app’s settings, and select or add a photo. For better results, hang a contrasting color bed sheet, blanket, or backdrop behind you.

Because a lot of people are setting up informal and ad-hoc Zoom sessions and sharing their URLs in public, Internet trolls have decided it would be fun to wreak havoc as the world burns. They share public meeting URLs on message boards and egg each other on, and then join those meetings and push pornography or racial epithets.

Fortunately, those running public meetings can take steps to prevent such disgusting behavior. Zoom posted a blog entry with all the settings and on 4 April 2020 changed default settings to require passwords for all meetings for free, single-host paid, and upgraded education accounts.

In the end, although Zoom requires hosts to create accounts and makes participants download an app (or navigate to a backup browser-based option), the user experience is sufficiently good and the free tier sufficiently capable that it ends up being the solution of choice when you don’t know all the participants.

However, it’s impossible to discuss Zoom without addressing the wide variety of security and privacy failures on the company’s part. They started with the 2019 revelation of a failure in judgment and software expertise that left macOS users potentially open to being spied upon (see “Zoom and RingCentral Exploits Allow Remote Webcam Access,” 9 July 2019).

More recently, the company has been rocked by revelation after revelation of further security and privacy lapses. The company has addressed most of them in a series of software updates for iOS, macOS, and Windows, changes in default settings, and server-side changes. On 1 April 2020, Zoom’s CEO posted an apology, saying that the company would freeze new features to focus on security, privacy, and trust, and describing how it would consult users, independent experts, and corporate security leaders. That statement was followed by additional blog posts, apologies, and explanations about how Zoom uses encryption in its service. For a complete list of Zoom’s problems and responses, see “Every Zoom Security and Privacy Flaw So Far, and What You Can Do to Protect Yourself” (3 April 2020).

Overview of Zoom:

- Platforms: every major platform and browser

- Maximum video participants: 100 (free tier), 200 and 300 on standard paid tiers

- Screen sharing: yes

- Moderation controls: yes (extensive)

- Extras: Virtual backgrounds, scheduling, reactions

Webex

As a side note, Cisco Webex now offers a set of options that is similar to Zoom’s free tier, including multi-platform support, host-based meetings, no required account, and up to 100 participants, though recording requires a separate desktop app. Webex’s free tier currently has no limit on meeting length.

However, Cisco expanded its free tier’s size and options as its way of helping during the pandemic, but the company hasn’t made a commitment to the long-term availability of all those added features. If you want unlimited sessions and aren’t worried about that feature potentially being rescinded, try Webex. Oddly, it takes several days for Webex to create an account after you sign up.

Consider Paid Options

If those services don’t offer the features you need, there are even more if you, your company, or your institution is willing to pay. The cost can be modest, and you or your employer might already have a subscription that covers it. Here are the leading options:

- Google Meet: For businesses using G Suite, Google has effectively split Hangouts into Google Chat for text chats in channels (or “rooms”) and Google Meet for large-scale videoconferencing. G Suite has tiers at $6, $12, and $25 per user a month, with limits of 100, 150, and 250 simultaneous participants in a videoconference. Meetings can be recorded at the highest tier.

- Microsoft Teams: Part of an Office 365 subscription, Teams is the online chat portion of Microsoft’s online suite. Videoconferencing for up to 250 participants is part of the $150-per-year tier and higher tiers. It includes screen sharing. One version also allows broadcasts to up to 10,000 people. Sessions can be recorded if you can meet a bewildering list of prerequisites. (You may see references to Skype for Business, which is not available for new users and is being phased out for existing users starting in 2021.)

- Slack: While Slack is largely known for channel-based text messaging and integrations with other services, it also includes videoconferencing with up to 15 people at a time in its paid tiers, which start at $8 per user per month. Slack allows screen sharing and a primitive form of onscreen drawing.

- Webex: While Webex has a free tier, as noted above, it’s primarily intended as an integrated business product. Service is charged for each host; there’s no fee for participants. The tiers are priced at $14.95, $19.95, and $29.95 per month for 50, 100, and 200 participants in each meeting, including the option to record meetings and produce meeting transcripts. Meetings may last 24 hours, although that limit is currently the same for its free tier. The $29.95-per-month tier requires at least 10 hosts to qualify for the plan.

- Zoom: Zoom also charges only per host for its paid tiers. For $14.99 per month, a single host can have meetings that last up to 24 hours, create a custom meeting ID, and employ additional administrative controls. Paid plans allow cloud-based recording and sharing of recordings, and those can be connected to the Otter AI-based transcript service for speaker-separated transcripts. At $19.99 per month (with a minimum of 10 hosts on the plan), each host can handle up to 300 simultaneous participants, among other benefits. There are additional paid tiers, and paid plans can add additional participants as needed.

Top-Down Management (Pants Optional)

The common, constant use of videoconferencing will change a lot of how the business and educational worlds work. In the past, many organizations have resisted going to virtual meetings, often for absolutely valid reasons. Those reasons, unfortunately, have now been thrown out of the window. The more agile you are at mastering tools and finding the right ones among your work, academic, social, and other groups, the better off you will be through this crisis and beyond.

In an upcoming article, I will dig into the related topic of how to set up your space for videoconferencing, suggest ways you can improve lighting and your appearance on video, and offer an array of tips for making the best or most fun use of your time—depending on the purpose.

I’m writing a book for Take Control Books about Zoom and would welcome your tips and input in the comments. I would also encourage you to download a free copy of Take Control of Working from Home Temporarily, a book I wrote to help people with the sudden adjustment in their working lives. It contains a number of videoconferencing tips, among many others provided by Take Control authors, TidBITS editors and contributors, and others who donated their experiences and insights.

Every Zoom Security and Privacy Flaw So Far, and What You Can Do to Protect Yourself

Zoom Makes Sweeping Changes to Address Security Criticisms

Since we published this article, Zoom has made numerous changes to address the problems we report on below, along with others to deal with issues that came to light after publication. The company created a new Privacy & Security portal detailing changes along with a link you can use to ask questions directly of the company’s CEO during his regular public sessions. We’re working on a followup article that will recap the changes, but in the meantime, make sure to keep your Zoom app up to date to take advantage of the many fixes.

Of all the tech companies that have benefitted from the massive shift to telecommuting that the global pandemic has forced, Zoom stands at the top. The company’s multi-platform videoconferencing software was well known before, being a frequently used, market-leading choice mentioned in the same breath as Adobe Connect, Cisco Webex, GoToMeeting, Microsoft Teams, and Skype. But now Zoom has become a verb among businesses, schools, and people making social connections.

That’s partly because of the scope of Zoom’s free tier, which allows up to 100 streaming video participants, and the way it has focused its service on scheduling or creating “meetings” that people can join with just a URL, either downloading a simple app on any platform or using an in-browser alternative. In “Videoconferencing Options in the Age of Pandemic” (2 April 2020), I examined all the major free options for videoconferencing, and Zoom stood out both among no-cost options and in a section in which I summarized paid services.

As the stock market has plummeted, Zoom’s share price has doubled—though that’s likely driven more by enthusiasm for the service rather than the ultimate size of the paid videoconferencing market. Zoom said on 1 April 2020 that daily meeting participants increased from 10 million to 200 million between December 2019 and March 2020. The fact that Zoom was able to handle a 20-fold increase in usage in that time is impressive.

But any accounting of Zoom’s success must also acknowledge a host of problems, too. Any time we discuss Zoom and consider recommending its use or thinking about its future, we have to look at a series of bad programming, security, marketing, and privacy decisions the company has taken.

Let me put it bluntly: Zoom is sloppy. Evidence of this began to accumulate last year with a screw-up that exposed macOS users to significant privacy exposure: your video camera could have been activated by visiting a page that loaded a malicious link. The problematic disclosures have accelerated this year with a series of errors in judgment and programming flaws. Zoom may have a top-notch technical solution and user experience, but the company deserves to take its knocks for slapdash and negligent programming.

Zoom also has made poor privacy decisions, some of which have already been remediated, by positioning itself more like a marketing firm than one that provides personal, academic, and business services over which we conduct private, confidential, or secret conversations.

Almost as bad, from my perspective, is that Zoom seemed unwilling to admit any failing, avoided apologizing, and didn’t provide a roadmap on how it will do better. Instead, it tended to fix problems while remaining on the defensive.

Zoom may face legal action over those statements and other matters. A class-action lawsuit based on California’s relatively new data protection law was filed on 30 March 2020 over the leak of data to Facebook described below. On the same day, New York State’s attorney general sent Zoom a letter asking for details on how it’s managing security risks given its history.

TidBITS contacted Zoom for its insights about how it has handled security and privacy issues, but the company didn’t reply. As I finished this article and in a few days that followed, however, Zoom publicly responded to disclosures of new security problems. The first response, unlike most previous ones, was a blog post with an apology and a full explanation. A subsequent post laid out the company’s plans for how it will improve its software and its culture around security and privacy. It’s a glimmer of hope for the future. A third responded to a privacy group’s investigation into the company’s weak choices in encryption algorithms and in routing some meeting traffic through China for non-Chinese participants. The rapid response and general frankness was in stark contrast to earlier behavior.

In this article, I walk through the many software, security, and privacy issues Zoom has encountered and its response to each.

You may prefer to not use Zoom after reading this article. For my part, I continue to rely on it, sometimes daily. However, many people—perhaps tens of millions—have to use Zoom for school and work. Given that not using it isn’t an option for them, I want to offer advice on configuring it as safely as possible.

A Tiny macOS Web Server and Automatic Reinstallation

In mid-2019, security researcher Jonathan Leitschuh posted a lengthy report on Medium about security flaws and undesirable behavior by Zoom software for macOS:

- The Zoom client app installed a tiny Web server without disclosing this to users.

- This Web server bypassed a security improvement in Safari designed to require users to click Allow each time a URL with an application-based link was loaded or the user’s Web browser redirected to such a URL. Instead of prompting, the redirection was captured by Zoom’s Web server, which launched the Zoom app.

- Zoom’s tiny Web server lacked basic security features, so an attacker could direct you to a URL or load a URL within a Web page and, either way, trigger the Web server to join a Zoom meeting without any prompt. That could allow the attacker to hear your audio and see your video. This attack worked only if you had changed the default settings to start audio or video automatically upon joining a meeting, something many users did.

- If you removed the Zoom client app, Zoom’s Web server remained in place and continued to run. If you subsequently clicked a link to join a Zoom meeting, the Web server would quietly and automatically reinstall and launch the Zoom client.

Leitschuh followed responsible security disclosure principles and alerted Zoom. It took him a few attempts to get the company to respond and more to get them to engage. He started an industry-standard 90-day countdown to his public disclosure well into that process. Zoom eventually agreed to make a few changes but disagreed with him on the severity of the vulnerability.

Leitschuh made his public disclosure on 8 July 2019. (See “Zoom and RingCentral Exploits Allow Remote Webcam Access,” 9 July 2019.) A media and consumer firestorm followed. Zoom tacked and decided to remove the Web server entirely from the install process. The following day, Apple took the unprecedented step of adding the Web server to its malicious software list distributed quietly and automatically to macOS, which uninstalled the Zoom Web server even if a user hadn’t installed an update.

Zoom’s response was inadequate. The company published a blog post and updated it several times as the public-relations debacle unfolded, but it never used any apologetic terms, and it included what the researcher claims was an inaccurate description of his interest in a bug bounty program, which companies run to offer fees for private submission of security flaws.

While Wired reported Leitschuh’s remark that Zoom CEO Eric Yuan had said he was sorry—“He came in and chatted with us and apologized and made a full about face.”—Wired offered no confirmation in the story from Zoom, and the company has never made a public statement of regret.

Action needed by you: None. Not only did Zoom remove the unwanted Web server, Apple’s security update deleted it for Mac users who didn’t update their Zoom app.

A Failure To Anticipate Repeated Attempts To Find Open Meetings

Part of designing an Internet-connected service for security and safety is to think maliciously: how would someone try to attack or break into your system? All too often, programmers and system administrators don’t get into that mindset or are discouraged from implementing a solution—even though there are piles of blog posts, white papers, conference talks, and books about security best practices.

Zoom fell into two of the oldest traps in the book with design and implementation flaws that could—and did—lead to unwanted parties joining open public meetings. Every Zoom meeting has a meeting ID that’s 9 to 11 digits in length. (You can optionally set a password, a practice that Zoom is increasingly encouraging. By default, meetings created by some kinds of accounts default to having a password; see more tips at the end of this article.)

Zoom’s first flaw was to provide an insufficient addressable space. In other words, a 9-to-11 digit number is too small relative to the number of meetings conducted. While using 9 digits allows for 900 million possibilities and using 11 digits gives you 90 billion possibilities, Zoom may be generating tens of millions of meeting IDs every day. (Zoom doesn’t allow a leading zero, so all IDs start with 1 to 9, reducing the total for each length by 10%.) That offers the opportunity for “collisions,” in which someone could test potential meeting IDs against those actually in use. (Zoom also creates a fixed 10-digit personal meeting ID for each account that can only be changed to another 10-digit ID at paid tiers.)

Security researchers at Check Point Research decided to probe this scenario for weaknesses. They wrote a script that generated random numbers in the range Zoom employs and tested them against Zoom’s site. They found that 4% of the randomly generated numbers matched actual meeting IDs!

Such a test shouldn’t have been possible, however, and that’s the second flaw. Zoom didn’t have a throttle on the server it uses to convert a meeting ID request into a Zoom meeting URL—and the server responded with an error for invalid IDs. Researchers could send thousands of URLs to Zoom’s server and quickly determine which were legitimate. If a malicious entity had done this, they could have then attempted to connect to valid meetings. (Throttles are not a new concept. Nearly 20 years ago, based on best-practice advice then, I built a throttle for my own Web sites that prevents large numbers of requests over short periods—I’m still using it today.)

Check Point used industry-standard disclosure principles as well and released its report on 28 January 2020; it had initially provided details to Zoom on 22 July 2019, just weeks after Zoom’s mistakes with the macOS app situation. Zoom was apparently more receptive to Check Point.

Zoom’s response was to block excessive requests to its meeting ID conversion URL and always return a Zoom meeting link instead of reporting whether the ID is valid or not. Only when you go through the overhead of connecting via a Zoom app or in-app browser connection can you determine if the meeting ID is legitimate.

However, on 2 April 2020, Trent Lo of SecKC, a group of folks who meet up for security talk in Kansas City, Missouri, sent details to Brian Krebs of Krebs on Security that the number-space flaw could still be exploited using “war dialing” methods reminiscent of dial-up modem days.

This required, in part, using a different IP address for every connection, subverting Zoom’s throttling approach. The tool the group developed had a whopping 14% success rate for finding public meetings. Krebs noted that the method used by the SecKC group also revealed “the date and time of the meeting; the name of the meeting organizer; and any information supplied by the meeting organizer about the topic of the meeting.”

The ultimate solution that Zoom will have to implement eventually is one I recall reading about in the mid-1990s, when it was already old hat: create a much larger addressable space. That’s typically done by mixing numbers and letters to increase the ID length substantially—to 20 characters, say—and reduce the odds of guessing a public meeting number to practically nil.

In the meantime, as of 4 April 2020, Zoom has changed the default behavior to require passwords for free accounts, upgraded education accounts, and its single-license (one paying host) account. The password settings cannot be disabled for these tiers and users, and most previously scheduled meetings have had passwords added to them.

This change effectively blocks “war dialing,” as even finding a valid meeting ID at random won’t allow a connection without the associated password.

Action needed by you: None. Remain vigilant when sharing Zoom URLs that embed the password, however, or when sharing a meeting ID and its associated password, as discussed in advice at the end of this article.

Leaking Behavior in iOS via Facebook’s Developer Kit

On 26 March 2020, Motherboard reported that its analysis of the Zoom app for iOS showed the software was sending information about users to Facebook even if the users didn’t have Facebook accounts. Zoom’s privacy policy did not disclose that this information transfer would take place (not that that would have made it that much better). Motherboard wrote:

The Zoom app notifies Facebook when the user opens the app, [and provides] details on the user’s device such as the model, the time zone and city they are connecting from, which phone carrier they are using, and a unique advertiser identifier created by the user’s device which companies can use to target a user with advertisements.

Given that the leak affected only the iOS version of Zoom and not any of the company’s other supported client apps, this seemed like a careless implementation of Facebook support, rather than an intentional violation of user privacy. Regardless of whether it was intentional or not, it was a violation of user privacy, and in some US states and some countries, such violations may subject a company to a fine or other sanctions.

Zoom initially didn’t respond to Motherboard, which provided details days ahead of publishing its story. Then, on 27 March 2020, Zoom told Motherboard that sending analytic data to Facebook was an error, claiming that it was Facebook’s fault (“we were recently made aware that the Facebook SDK was collecting unnecessary device data”). Zoom updated its iOS app to remove the Facebook SDK entirely, instead forcing Zoom users who want to log in using their Facebook credentials to go through the browser-based dance used by other apps and Web sites.

Unlike previous instances, Zoom expressed regret via a statement this time, saying: “We sincerely apologize for this oversight, and remain firmly committed to the protection of our users’ data.”

Action needed by you: None. Zoom has updated its software to remove the Facebook connection.

Zoom’s Privacy Policy Positioned It as a Marketing Firm

What is Zoom? It would seem to be a company that provides group communication tools that largely center around videoconferencing. But if you read Zoom’s privacy policy before the end of March, you might have thought its business was marketing and the product it sold was you.

With increased attention on Zoom, privacy and consumer advocates are focusing on the terms of service and promises the company makes about keeping its users’ audio and video sessions, text chats, and personal information private. In late March, the venerable magazine Consumer Reports, Internet thinker and Cluetrain Manifesto author Doc Searls, and others engaged the company in a full-court press about its stated policies.

Zoom’s privacy policy had been extremely broad. As Consumer Reports noted, the company could store and collect personal data and share it with third parties (including advertisers). That’s not completely unusual, except that personal data included video sessions, automatically generated transcripts, the contents of shared whiteboards, uploaded documents, instant messages and chat sessions, the names of everyone on a call, and the contents of cloud storage.

Whoof. A bit much! After a deluge of reporting and opinionating about its privacy policy, Zoom released a dramatic overhaul on 29 March 2020. It now explicitly excludes all the contents of Zoom sessions—audio, video, chats, documents, and so on—and clarifies exactly how Zoom uses personally identifiable information, like your email address.

Action needed by you: None. Zoom’s changes are effectively retroactive because the company claims it never used any of the data that its policy said it could.

A Zoom Host Knew When Your Attention Slipped

This wasn’t a security flaw, and it wasn’t exactly primarily a privacy problem, but it’s worth noting in passing. Zoom optionally let the host of a meeting know if you had shifted your focus away from the Zoom app to another piece of software for more than 30 seconds.

As Motherboard explained, “attention tracking” put a small icon in the list of participants indicating that they had moved out of the app. The idea was to let the host know if people had stopped paying attention, but it’s rare to have a videoconference in which people don’t need to switch to other apps for legitimate reasons. The tracking may not have worked correctly with all of Zoom’s in-browser conference apps, either.

In some cases, participants in a meeting operate under rules that allow for some kinds of limited, appropriate monitoring, such as employees in a business meeting or students participating in a teacher-led class session. In others, it might be unwanted or inappropriate.

Regardless, in response to the negative feedback, Zoom removed this feature on 1 April 2020.

Action needed by you: None.

Misuse of macOS Preflight Installation Scripting

A few days ago, a forum member at Hacker News posted their realization that Zoom’s macOS installer bypasses the normal multi-step process in a standard installer we are all familiar with. In a typical installation process, you may be asked onto which disk or for which users to install an app, then asked to approve an end-user license agreement (EULA), and finally have to click Install.

On 29 March 2020, “mrpippy” posted at Hacker News, saying that he noticed that the installation happened quite early on during what’s called the “preflight” process. That’s the stage at which an installer may check to see where and how it should install and require user prompts to proceed. (Apple breaks the installer system into multiple steps and allows developers to run scripts at each of those steps.)

In relation to this approach in a round-up of recent disclosures about Zoom’s security and privacy, Daring Fireball’s John Gruber wrote:

Again, that’s clearly not an oversight or honest mistake. Everyone knows what ‘preflight’ means. It’s a complete disregard for doing things properly and honestly on Zoom’s part. There’s no way to check what files will be installed and where before their installer has gone ahead and installed them.

It’s easy to argue this kind of installer behavior is more akin to malware, even though you intended to install the software. It’s another incidence of behavior by Zoom that avoids disclosure and bypasses user intent in the interest of ensuring its software is rapidly installed.

On 31 March 2020, Zoom’s CEO responded directly to a technical researcher on Twitter who popularized the finding there stating, “Your point is well taken and we will continue to improve.” On 2 April 2020, Zoom released an updated version that follows normal installation practices. The researcher told The Verge, “I must say that I am impressed.”

Action needed by you: None. The next version of Zoom you install will use Apple’s installer system in the appropriate fashion.

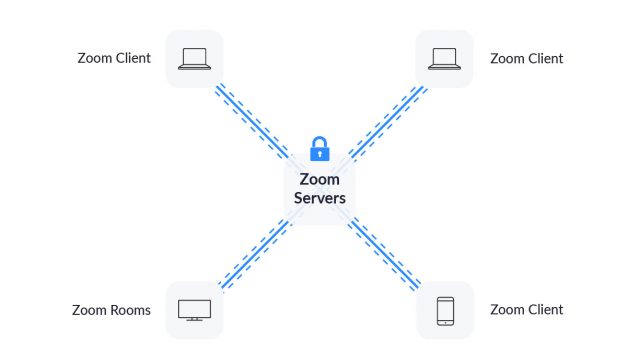

Confusion over Zoom’s Explanation of End-to-End Encryption

End-to-end encryption, sometimes abbreviated E2E, is one of the most powerful ways to protect your privacy. Prior to the spread of E2E, most encryption used a client/server approach with digital certificates, such as with HTTPS for a secure Web link.

Instead, E2E encryption secures data at each endpoint, which could be a device or a piece of software. The endpoints possess encryption keys that are typically generated locally. PGP, invented in 1991, allowed encrypted peer-to-peer communication using public-key cryptography. Your PGP software generated a key pair: one key was public and could be shared; the other key was private, and you had to keep it secret. Messages encrypted with the public key could be decrypted only with the private key. Public messages could also be signed with the private key so that a recipient could verify the message hadn’t been modified since it was created.

Public-key cryptography eventually became the basis of secure person-to-person and group-based communications. With PGP, you had to start by figuring out how to trust another person’s public key. By creating a centralized public-key infrastructure, a company manages that problem by distributing its own root of trust, a bit of global validation, as part of its software.

Skype pioneered this approach, having its client apps generate encryption keys that were stored only in the client. The company itself never needed to know (and, due to the design of the system, couldn’t know) what the keys were. Apple’s iMessage and FaceTime work similarly.

With this kind of E2E encryption, the company that maintains the public-key infrastructure—Microsoft or Apple, in this case—doesn’t know any of the encryption keys, but because it controls the root trust, it could modify the system in such a way to intercept or decrypt data.

You can take E2E encryption a big step further by generating encryption keys at endpoints such that the company running the central system can never access them. Apple relies on endpoint-controlled keys with iCloud Keychain, certain aspects of facial recognition details in Photos, and HomeKit Secure Video. The Signal communication app relies on the same approach for its messaging system.

In either E2E approach, without the endpoint encryption keys, an attacker could intercept all the data transmitted and never be able to decipher it. Nor could the company hand over data to any government authority. And the system is highly resistant, maybe impenetrable, because the keys are unrecoverable.

Zoom has marketed itself as offering end-to-end encryption. But on 31 March 2020, The Intercept reported that Zoom appeared to employ a simpler form of transport-layer security in which connections from meeting endpoints are encrypted to Zoom’s central servers, where the data is decrypted (but not stored) before being re-encrypted and transmitted to other participants via text, audio, or video.

A spokesperson from Zoom seemed to confirm this behavior by telling The Intercept in a statement, “Currently, it is not possible to enable E2E encryption for Zoom video meetings,” as well as, “When we use the phrase ‘End to End’ in our other literature, it is in reference to the connection being encrypted from Zoom end point to Zoom end point.”

However, on 1 April 2020, Zoom published an apologetic blog post in which Chief Product Officer Oded Gal explained that Zoom operates something closer to the first kind of E2E system (centralized company management of keys) than the second (endpoint-only possession of keys).

Zoom apparently does provide end-to-end encryption between participants using Zoom native and Web apps. The data passes across Zoom’s servers without decryption and re-encryption. However, in order to connect sessions to other kinds of services, Zoom operates “connectors” that will decrypt data in certain circumstances. For instance, if you enable the company’s cloud-based recording option, sessions have to be briefly decrypted within Zoom’s cloud system. Similarly, for someone to call into a Zoom meeting from a regular phone or stream a Zoom meeting through a conduit, the session has to be decrypted.

This means that Zoom—like Microsoft with Skype or Apple with iMessage and FaceTime—retains the potential ability to intercept and view session data or disclose it to parties outside a meeting and other than the host. Gal wrote in the blog post:

Zoom has never built a mechanism to decrypt live meetings for lawful intercept purposes, nor do we have means to insert our employees or others into meetings without being reflected in the participant list.

This winds up being a bit of having one’s cake and eating it, too, because Zoom wants to offer E2E but also client/server connections. If you never use any of Zoom’s connectors and trust the CEO’s statement, you get the benefits of E2E. But if you enable a connector, Zoom has to decrypt some part of the stream—audio for a phone call, audio and video for a cloud-based recording—which renders the approach much more vulnerable and less secure. For instance, an attacker could conceivably be able to force cloud-recording of sessions quietly and redirect the data stream with no need to break into the actual meeting. That’s simply infeasible with Skype, iMessage, or FaceTime without Microsoft or Apple rewriting its software. (None of these firms offer sufficient independent code auditing, however, so it’s impossible to ensure that my statement is absolutely true.)

On 3 April 2020, the nonprofit privacy and security research organization Citizen Lab released a report examining Zoom’s E2E technology and other implications (discussed below). Citizen Lab says Zoom uses a single shared key among all meeting participants, that the key generated uses a weak algorithm susceptible to cracking, and that the keys are generated not by endpoints, but by company-run servers.

Gal noted in the Zoom blog post that the company already offers a corporate-focused option that keeps all encryption within a company’s local control, and it plans to offer more such choices later in the year, though likely just to paid accounts of a minimum size. However, without more detail about key algorithm and generation, that isn’t entirely reassuring.

The Intercept suggests Zoom may have violated Federal Trade Commission regulations. While the FTC doesn’t enforce how a company manages data, it does have legal oversight over trade practices and can sue to enforce changes and levy penalties. If Zoom’s advertising and description of its encryption comprised unfair or deceptive trade practices, the FTC could opt to intervene.

Ashkan Soltani, the former FTC chief technologist and an avid investigator of security and privacy practices, told The Intercept:

If Zoom claimed they have end-to-end encryption, but didn’t actually invest the resources to implement it, and Google Hangouts didn’t make that claim and you chose Zoom, not only are you being harmed as consumer, but in fact, Hangouts is being harmed because Zoom is making claims about its product that are not true.

Taking Zoom’s explanation as accurate, calling their method E2E is not a distortion, though it now has several caveats that were not previously understood.

What’s potentially as useful to note here is that Zoom’s blog post begins with the statement, “we want to start by apologizing for the confusion we have caused by incorrectly suggesting that Zoom meetings were capable of using end-to-end encryption.” Plus, its author notes near the end, “We are committed to doing the right thing by users when it comes to both security and privacy, and understand the enormity of this moment.” That’s an evolution for Zoom.

On 3 April 2020, in a blog post, CEO Eric Yuan responded directly to the Citizen Lab report and promised improvements on encryption: “We recognize that we can do better with our encryption design.”

Action needed by you: None. But consider whether Zoom’s E2E encryption implementation matches the level of security you are looking for.

Assuming Everyone with the Same Domain Knew Each Other

On 1 April 2020, Motherboard reported that Zoom shares contact information among everyone whose email address has the same domain name, excluding major consumer hosting and email services like Gmail, Hotmail, and Yahoo. The company effectively assumes that all users of that domain work for the same company without validating in any fashion that the assumption is true. (In Slack, a vaguely similar feature allows a private workspace owner to allow anyone using an email in a given domain to be invited to the workspace and automatically added. But that’s for private groups, managed by the workspace owner, and is opt-in.)

Zoom does maintain an extensive “blocklist” of domains to exclude, but it’s still just a list. For any user at any domain not included in that list, the Contacts tab in the Zoom client allows access to the email address, full name, profile picture, and current status of all other registered users of that domain. That also allows incoming one-to-one audio and video calls to that person.

Zoom’s response to Motherboard was to note that it had added ISP domains Motherboard inquired about, such as a few popular Dutch providers, but otherwise has left its policy the same.

Action needed by you: Zoom says people and organizations can use its Submit a Request page to request that a domain be added to its blocklist.

Improper Vetting of Link Conversion on Windows

Zoom automatically converts anything it thinks is a link into a hyperlink in a chat session. In Windows, that included file paths that, when clicked, opened remote SMB file-sharing sessions! If a user clicked such a link, their Windows system would send encrypted but vulnerable credentials that use an outdated security approach. A remote attacker could then access the machine.

A link could also be formatted to point to a DOS program under Windows. If clicked, Windows asks a user to confirm that they want to run the program.

Zoom fixed this vulnerability on 1 April 2020.

Action needed by you: None.

Harvesting of Participant Information via a LinkedIn Conduit

On 2 April 2020, the New York Times reported that participants in a Zoom meeting could have substantial personal information made available to any other participant who had signed up for LinkedIn Sales Navigator, a tool designed for finding new prospects for marketers. Without the act being disclosed, every Zoom participant’s name and email address (if available) was matched against LinkedIn’s database and, if they had a profile, connected to it.

This could be true even if the user didn’t provide their correct name when connecting to a particular meeting, as Zoom relied on the user’s account profile if logged in. Any participant who subscribed to the LinkedIn feature could merely hover over a participant’s name to see their LinkedIn profile card.

Zoom removed the feature on 1 April 2020 after the New York Times contacted the company to ask about it.

Action needed by you: None.

Use of Vulnerable Mac Frameworks Leads to Zero-Day Local Exploits

On 30 March 2020, noted Mac and iOS security researcher Patrick Wardle posted a lengthy entry on his Objective-See blog about two “zero-day” bugs that leave Zoom’s Mac users vulnerable to exploits by someone who can gain access to their computer (which seems less likely in today’s stay-at-home days). These exploits can’t be invoked remotely unless a malicious party could embed the exploit in software they convince someone to download and install, such as a Trojan horse or malware disguised as something useful.

Wardle apparently didn’t provide advance disclosure to Zoom, hence the “zero-day” term, which means the vulnerability remains exploitable at the time it is revealed. Since these bugs are local-only problems that can be exploited only during a Zoom app installation or update, the likelihood of an attacker taking advantage of them is low.

One bug could let an attacker replace a script that’s part of Zoom with software of their choosing that would be installed with the highest privileges. The other could let a ne’er-do-well access a Mac’s microphone and camera without the knowledge or permission of the user.

Zoom fixed these issues and released a new version of the client on 1 April 2020.

Action needed by you: Install the latest version of Zoom for macOS by choosing Check for Updates from the zoom.us menu.

Zoom Chat Transcripts Export a Host’s Private Messages

When you host a meeting with a paid account, you can opt to save a recording of the meeting. That can include a text transcript of public chat messages sent among participants, and all participants gain access to that transcript as well as the video recording.

But it will also include all private messages between the host and other participants. A professor posted this discovery on Twitter, and Forbes confirmed it with Zoom. Private messages among other participants aren’t included.

This is a bad design choice, because private messages should, by their nature, remain private. Zoom explains in its documentation for saving in-meeting chats:

You can automatically or manually save in-meeting chat to your computer or the Zoom Cloud. If you save the chat locally to your computer, it will save any chats that you can see– those sent directly to you and those sent to everyone in the meeting or webinar. If you save the chat to the cloud, it will only save chats that were sent to everyone and messages sent while you were cloud recording.

It’s all too easy to end up with something embarrassing in a chat that could be saved or accidentally shared later.

Action needed by you: If you’re a host, either don’t engage in a private chat that could be problematic or have the discussion in a separate secure app, such as Messages.

Chinese Ownership or Involvement